From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement

Abstract

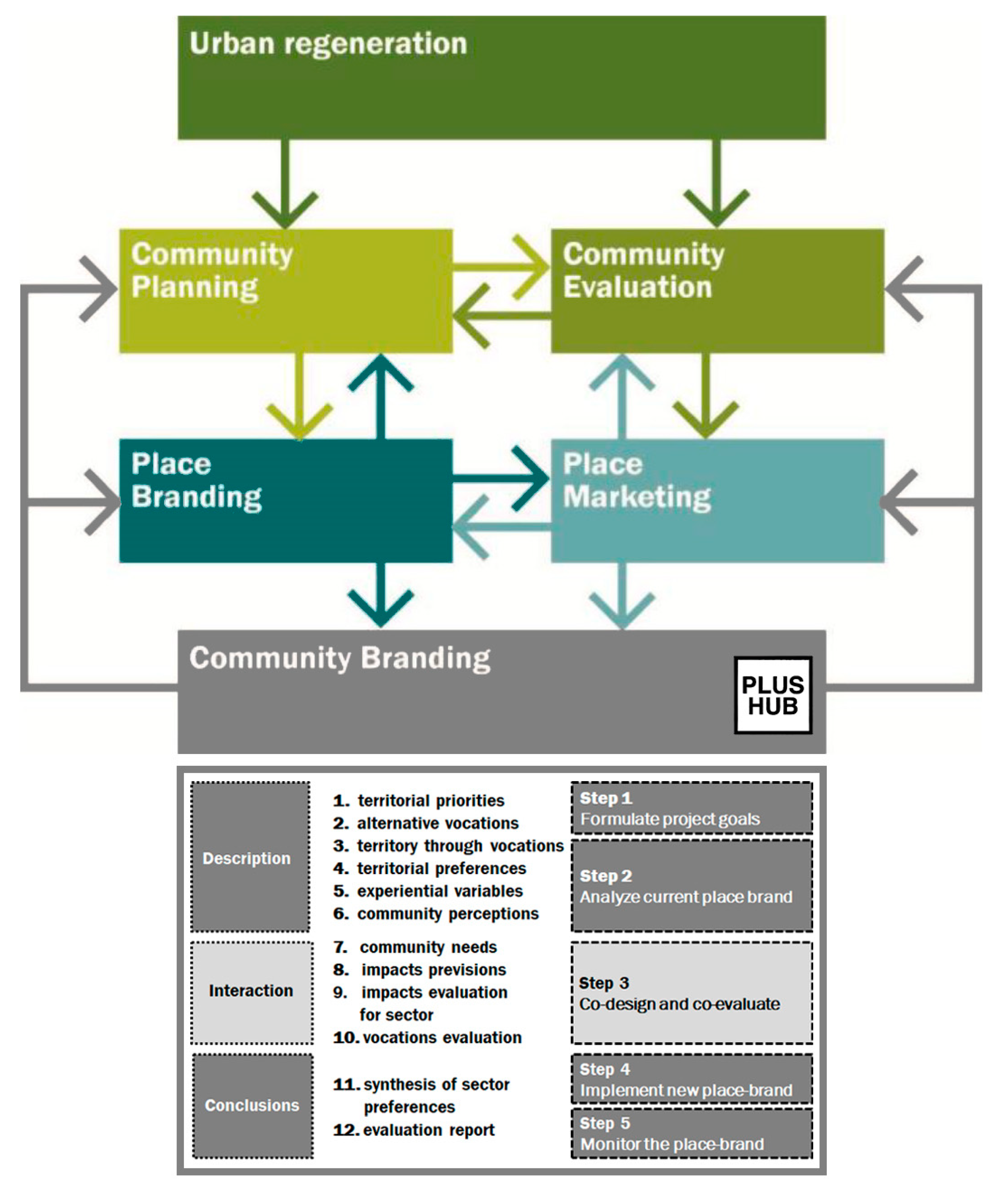

1. Introduction

- Which cultural values come into play and how can these be “extracted” from the territory?

- Who are the relevant actors and what role do they play in this process?

- What are the appropriate assessment, monitoring and action tools?

- Formulate project goals (vision, mission, objectives);

- Analyze current place brand (perceived identity and image, and projected image);

- Design place brand essence;

- Implement new place brand;

- Monitor the place brand.

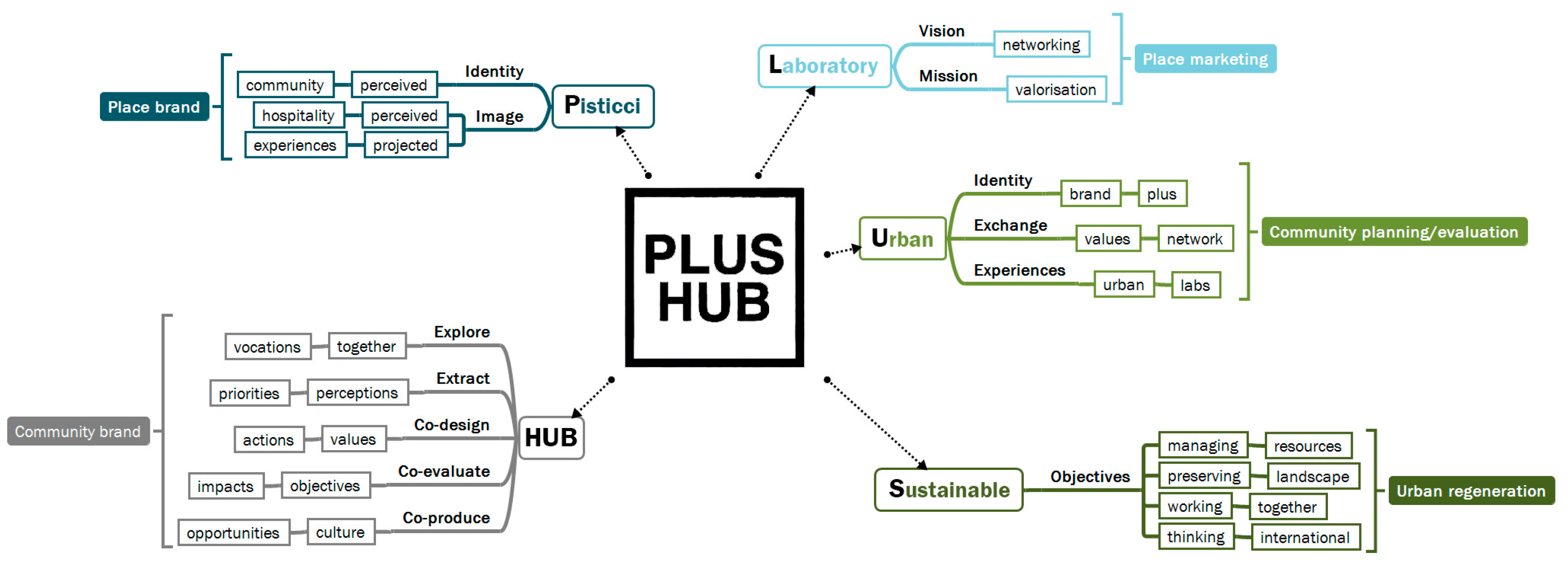

2. Community Branding Approach: Materials and Methods

2.1. Step 1 Formulate Project Goals

- Vision: “Networked Pisticci” a network of heritage and resources between tradition and innovation;

- Mission: Enhancing the territorial specificities and the local community;

- Goals:

- (a)

- Favor the efficient management of human and territorial resources;

- (b)

- Identify protective measures of the cultural heritage;

- (c)

- Develop community actions for an identity-oriented development of the historic center;

- (d)

- Plan meetings for international exchange on the potential and challenges of the territory.

2.2. Step 2 Analyze Current Place Brand

- Understand the perceived identity;

- Identify the perceived image;

- Clarify the projected image.

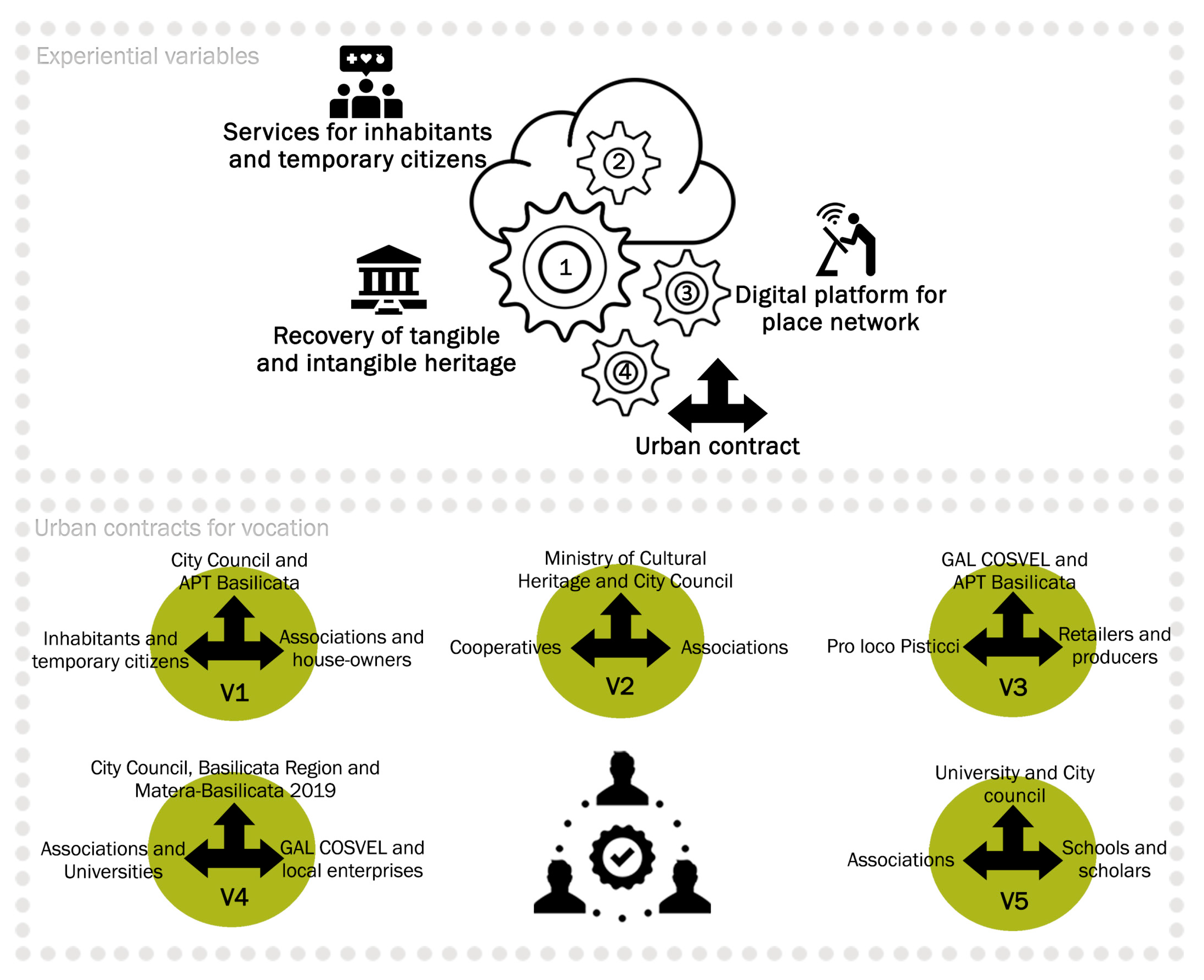

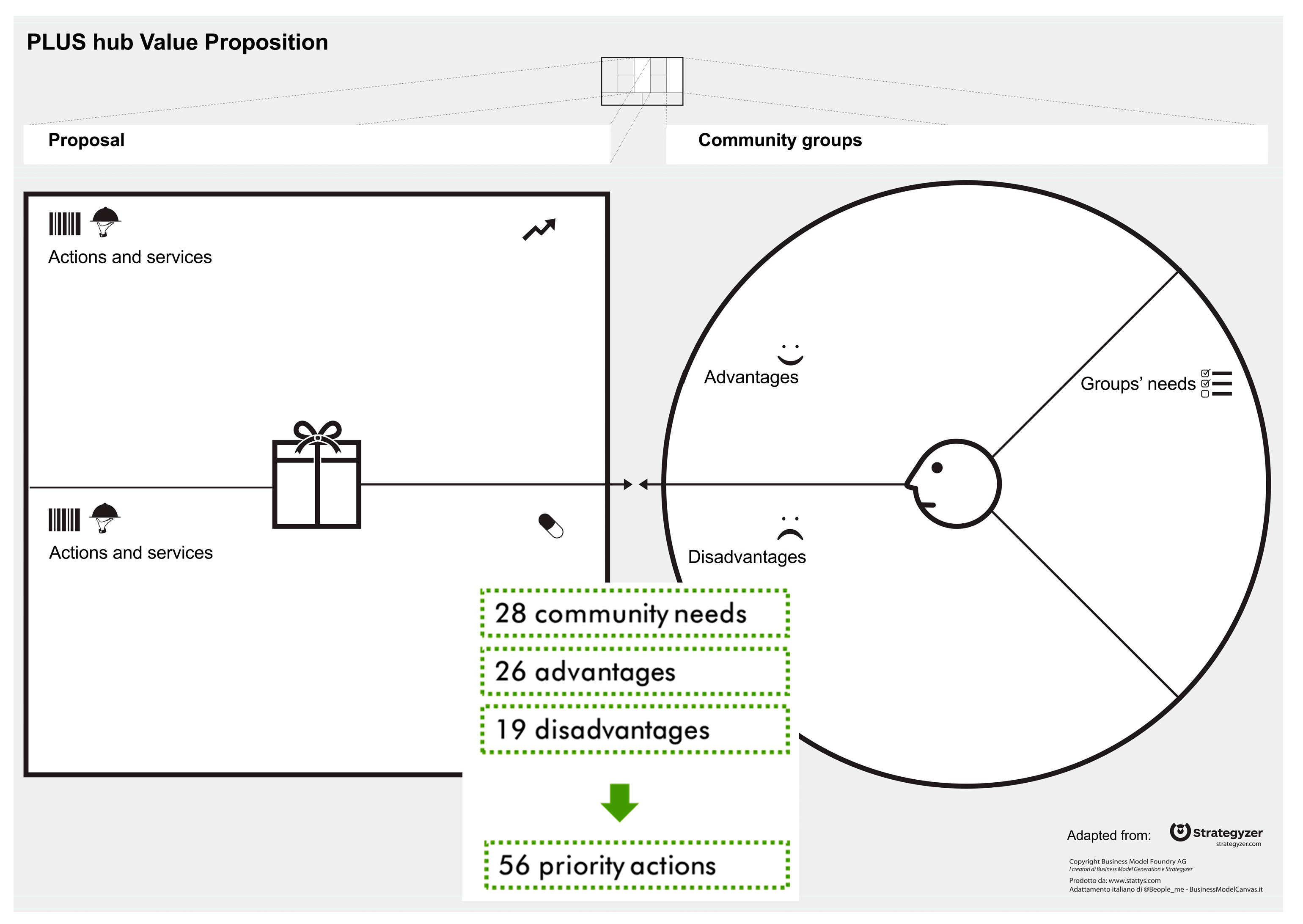

2.3. Step 3: Co-Design and Co-Evaluate

- Brand identity;

- Interaction among values;

- Territorial experiences.

- Regeneration of the material and immaterial heritage;

- Digital platform;

- Services for citizens and temporary residents;

- “Urban contract”.

2.4. Step 4 Implement New Place Brand

- Construct shared territorial landmarks (construction);

- Activate “PLUS community” processes (cooperation);

- Communicate the PLUS brand (communication).

2.5. Step 5 Monitor the Place Brand

- Evaluate and monitor the level of awareness of the PLUS brand by the actors to whom it is addressed and by the partner subjects, using specific evaluation methods and techniques;

- Evaluate and monitor the change induced by the perceived identity/image and the level of loyalty, using evaluation methods and techniques with particular reference to potential users such as tourists, investors, traders and citizens;

- Evaluate and monitor the impacts of the designed image, carrying out an assessment linked to data relating in particular to: media coverage, online communities, blogs, Facebook, Twitter, virtual communities and online virtual worlds, etc.

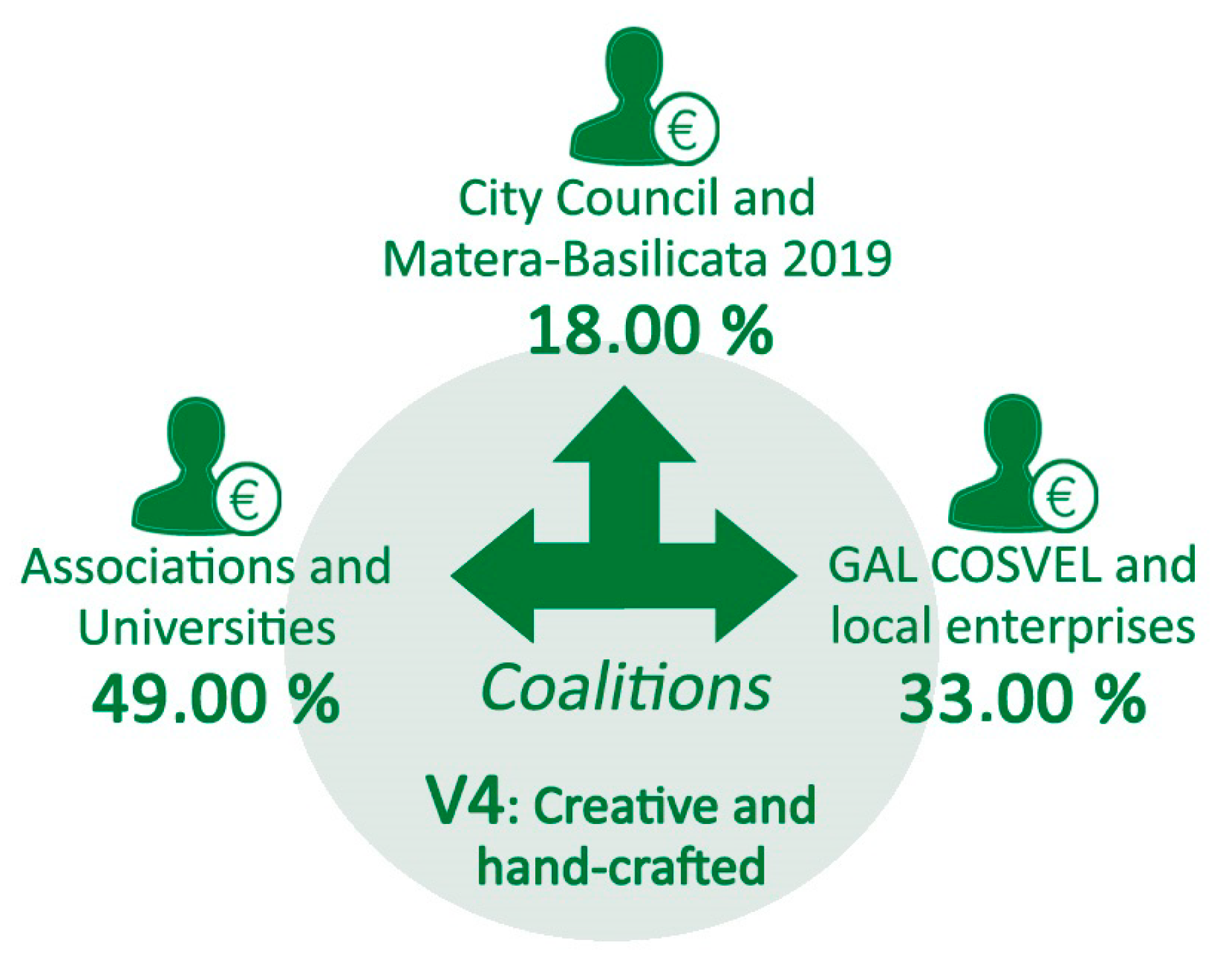

3. PLUS Hub Case Study Results

- V 1: the sacred and the profane

- V 2: agricultural tradition

- V 3: landscape and biodiversity

- V 4: hotel industry and resilient community

- V 5: artisan and creative density

- Brand identity: “Pisticci Urban Sustainable Laboratory” (PLUS);

- Interaction among values: Pisticci as a network of urban sustainable organizations;

- Territorial experiences: Pisticci as the place for urban sustainable laboratories rooted into local traditions and landscape. This is summarized in a needs/project actions matrix for the PLUS hub, divided by governance mode, cultural activities, and economic sustainability;

- elaboration of matrices of economic, social and cultural impacts on community sectors for the enhancement of heritage and urban regeneration;

- co-evaluation of alternative vocations through the multi-criteria PROMETHEE method.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- Which cultural values come into play and how can these be “extracted” from the territory?

- Who are the relevant actors and what role do they play in this process?

- What are the appropriate assessment, monitoring and action tools?

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerquetti, M.; Montella, M. Paesaggio e patrimonio culturale come fattori di vantaggio competitivo per le imprese di prodotti tipici della regione Marche (Landscape and Cultural Heritage as Factors of Competitive Advantage for Agrifood Firms in Marche Region). In Proceedings of the XXIV Convegno Annuale di Sinergie Il Territorio Come Giacimento di Vitalità per L’impresa, Referred Electronic Conference Proceeding, Lecce, France, 18–19 October 2012; pp. 549–562. [Google Scholar]

- CHCfE Consortium Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe. 2015. Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/our-work/policy/cultural-heritage-counts-europe/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- World Heritage Centre. UNESCO Thematic Indicators for Culture in the 2030 Agenda; World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mısırlısoya, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Commission A New European Agenda for Culture; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, E.; Sacco, P.L.; Blessi, G.T.; Cerutti, R. The impact of culture on the individual subjective well-being of the Italian population: An exploratory study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2011, 6, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.; Bridge, G. Gentrification in A Global Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 1134330650. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Williams, P. Gentrification of the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat State of the World’s Cities Report 2004/2005. In Globalization and Urban Culture; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; Available online: https://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=1163 (accessed on 24 February 2015).

- Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, London, Tokio; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 0691070636. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. On concentration and centrality in the global city. World Cities A World Syst. 1995, 63, 71. [Google Scholar]

- KEA European Affairs. The Economy of Culture in Europe; KEA European Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- KEA European Affairs. Culture for Cities and Regions; KEA European Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Creativity and urban governance. Policy Stud. 2004, 25, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markusen, A. Cultural planning and the creative city. In Proceedings of the annual American Collegiate Schools of Planning Meetings, Citeseer, Ft. Worth, TX, USA, 12 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. City and Creative Class; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.L. L’ascesa della Nuova Classe Creativa: Stile di Vita, Valori e Professioni; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taormina, A.; Calvano, G. The European Capitals of Culture between employment and voluntary work. Econ. Cult. 2014, 24, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, G.; Scharff, E.; Ye, Y. Fostering social creativity by increasing social capital. In Social Capital and Information Technology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 355–399. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Q. 2001, 22, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Glocalization and hybridity. Glocalism J. Cult. Polit. Innov. 2013, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, L.; Vinerean, S. The glocal strategy of global brands. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2010, 5, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding–Glocal, Physical and Virtual Identities Constructed, Imagined or Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The big idea: Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Grandy, C. The principle of maximum entropy and the difference between risk and uncertainty. In Maximum Entropy and Bayesian Methods; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1991; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Srnicek, N. Platform capitalism; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, M.; Sanyal, R. Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London. Urban Stud. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagata, E.W.; Translation, E.; Kerr, D. White Paper on Creativity towards an Italian Model of Development; Ministry of Heritage and Cultural Activity: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative Industries; European Comission Green Paper; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S. L’approccio sistemico vitale per lo sviluppo del territorio. Sinergie 2011, 84, 47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, L. Felicità e Beni Relazionali. Available online: http//journaldumauss.net/IMG/pdf/FELICITa-beni_rel.pdf2011 (accessed on 10 January 2016).

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. The entropy law and the economic problem. In Valuing Earth Econ. Ecol. Ethics; Daly, H.E., Townsend, K.N., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 75–88. ISBN 0262540681. [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, A. Bioeconomía y Capitalismo Cognitivo; Hacia un nuevo; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; ISBN 0521663636. [Google Scholar]

- Forester, J. Beyond Dialogue to Transformative Learning: How Deliberative Rituals Encourage Political Judgment in Community Planning Processes. In Evaluating Theory-Practice and Urban-Rural Interplay in Planning; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1997; Volume 37, pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Pflieger, G. The Social Fabric of the Networked City; EPFL Press: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G. Distretti culturali evoluti e valorizzazione del territorio. Glob. Local Econ. Rev. 2005, 8, 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, P.; Ferilli, G.; Tavano Blessi, G. From Culture 1.0 to Culture 3.0: Three Socio-Technical Regimes of Social and Economic Value Creation through Culture, and Their Impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.; Ferilli, G.; Blessi, G.T. Understanding culture-led local development: A critique of alternative theoretical explanations. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2806–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, 1985; New York Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vorhies, D.W.; Morgan, N.A. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ache, P. Cities between Competitiveness and Cohesion: Discourses, Realities and Implementation; Ache, P., Andersen, H.T., Maloutas, T., Raco, M., Taşan-Kok, T., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Volume 93, ISBN 140208241X. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, E. Modelli ibridi di partnership pubblico-privato nei progetti urbani. Sci. Reg. 2009, 8, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G. Community branding as a collaborative decision making process. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2017), Trieste, Italy, 3–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G. Processi decisionali innovativi per la valorizzazione del patrimonio culturale: Le imprese culturali e creative sostenibili. In Patrimonio e Città Storiche Come Poli di Integrazione Sociale e Culturale, Sostenibilità e Tecnologie Innovative; Genovese, R.A., Ed.; Giannini Editore: Napoli, Italy, 2018; pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Cerreta, M. Il patrimonio culturale: Strategie di conservazione integrata e valutazioni. Econ. Cult. 2001, 2, 175–186. Available online: https://www.rivisteweb.it/doi/10.1446/12766 (accessed on 12 March 2015). [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Competitive identity: The new brand management for nations, cities and regions. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 14, 474–475. [Google Scholar]

- Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Parker, C.; Quin, S.; Rinaldi, R.; Byrom, J. Town centre management models: A European perspective. Cities 2009, 26, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Transition management: Reflexive governance of societal complexity through searching, learning and experimenting. In Managing the Transition to Renewable Energy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 15–46. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Diappi, L. Adaptive Evaluations in Complex Contexts: Introduction. Sci. Reg. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Panaro, S. From perceived values to shared values: A multi-stakeholder spatial decision analysis (M-SSDA) for resilient landscapes. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The competitive advantage of nations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cercola, R.; Bonetti, E.; Simoni, M. Marketing e Strategie Territoriali; EGEA Spa: Evanston, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 882381183X. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, A. La Marca Nell’economia Dell’informazione. Per una Teoria dei Brand; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2010; ISBN 8856827042. [Google Scholar]

- Lury, C. Brands: The Logos of the Global Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, L. The Rise of Brands; Berg Publisher: Oxford, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://books.google.it/books?hl=it&lr=&id=FGetAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP7&dq=The+Rise+of+Brands&ots=kHH3x9iEIH&sig=rrNdFsoPnOGcFeT-pGANCJCbaUY#v=onepage&q=The%20Rise%20of%20Brands&f=false (accessed on 22 April 2016).

- Ma, W.; Schraven, D.; de Bruijne, M.; De Jong, M.; Lu, H. Tracing the origins of place branding research: A bibliometric study of concepts in use (1980–2018). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, V.-A.; Rezeanu, C.-I.; Briciu, A. Online Place Branding: Is Geography ‘Destiny’in a ‘Space of Flows’ World? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaynay, C.; Lee, J. Place Branding and Urban Regeneration as Dialectical Processes in Local Development Planning: A Case Study on the Western Visayas, Philippines. Sustainability 2020, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B. Destination Branding for Small Cities: The Essentials for Successful Place Branding; Creative Leap Books: Portland, OR, USA, 2007; ISBN 0979707609. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.A.; Rowley, J. Rethinking Strategic Place Branding in the Digital Age. In Rethinking Place Branding; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Cities in a World Economy; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 148334228X. [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie, K. City Branding: Theory and Cases; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 0230241859. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, G.; Trillo, C. Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Storico-Architettonico e Promozione D’impresa: Il Caso the Brewery, Boston; BDC. Bollettino Del Centro Calza Bini: Naples, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clemente, M.; Giovene di Girasole, E. Friends of Molo San Vincenzo: Heritage Community per il recupero del Molo borbonico nel porto di Napoli. In Il Valore del Patrimonio Culturale per la Società e le Comunità, la Convenzione del Consiglio d’Europa tra Teoria e Prassi; Pavan Woolfe, L., Pinton, S., Eds.; Linea Edizioni: Venice, Italy, 2019; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. Destination Branding: Creating the Unique Destination Proposition; Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, E. City Marketing: Towards an Integrated Approach; Erasmus University Rotterdam Publisher: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker, S.; Knubben, E.; Beckmann, S.C. Your city, my city, their city, our city: Different perceptions of a place brand by diverse target groups. In Proceedings of the the International Conference Thought Leaders in Brand Management, Lugano, Switzerland, 18–20 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. The Anholt-GMI city brands index how the world sees the world’s cities. Place Brand. 2006, 2, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olins, W. Branding the nation—The historical context. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Place Brand Observer Place Branding vs. Place Marketing. What’s the Difference?—Quick Guide. 2016. Available online: https://placebrandobserver.com/difference-place-branding-marketing-explained/ (accessed on 26 February 2016).

- Juan Carlos Belloso Rebranding Barcelona: City for Business, Talent, Innovation. Available online: http://placebrandobserver.com/rebranding-barcelona-city-branding-case-study/ (accessed on 13 March 2015).

- Rotterdam Brand Strategy. 2008. Available online: www.rotterdam.nl/rotterdamworldbrand (accessed on 25 November 2015).

- Owen, J. From ‘Turin’ to ‘Torino’: Olympics put new name on the map. Natl. Geogr. News 2006. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/2/turin-torino-italy-olympics/#:~:text=The%20city%20in%20Italy%20(map,a%20decision%20by%20the%20IOC (accessed on 10 May 2015).

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.X. City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2009, 26, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comitato Matera 2019 Dossier finale di Matera 2019—Open Future. 2014. Available online: https://www.matera-basilicata2019.it/it/news/550-il-dossier-di-matera-2019-%C3%A8-on-line.html (accessed on 10 September 2015).

- Gaber, J.; Gaber, S. Qualitative Analysis for Planning and Policy: Beyond the Numbers; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Daldanise, G. Place (Based) Branding e Rigenerazione Urbana. 2016. Available online: https://www.urbanit.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/160825-Gaia-Daldanise.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2016).

- Lichfield, N. Community Impact Evaluation; University College Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The rise and rise of culture-led urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Daldanise, G.; Sposito, S. Public spaces culture-led regeneration: Monitoring complex values networks in action. Urbani Izziv/Urban Chall. J. 2018, 29, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnaby, G.; Medway, D. What about the ‘place’in place marketing? Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Voogd, H. Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1990; Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19911895412 (accessed on 2 October 2016).

- Kavaratzis, M. From City Marketing to City Branding: An Interdisciplinary Analysis with Reference to Amsterdam, Budapest and Athens; Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2008; Available online: https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/publications/pub(8a350ad6-8e60-4a67-8773-18380fe72855).html (accessed on 2 July 2016).

- Moilanen, T.; Rainisto, S. City and destination branding. In How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 77–146. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M. Cities and their brands: Lessons from corporate branding. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2009, 5, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. Towards a strategic place brand-management model. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place Brand Observer The Five Steps of Successful Place Branding Initiatives—Quick Guides. 2016. Available online: https://placebrandobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/TPBO-Quick-Guide-Place-Branding-Process.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2016).

- Kavaratzis, M.; Warnaby, G.; Ashworth, G.J. Rethinking Place Branding; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, B.J. Focus groups and the nature of qualitative marketing research. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 353–364. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002224377701400311 (accessed on 10 March 2015). [CrossRef]

- Supphellen, M. Understanding core brand equity: Guidelines for in-depth elicitation of brand associations. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 42, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, G.R.; Iacobucci, D.; Calder, B.J. Using network analysis to understand brands. NA-Adv. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 12102959. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J.D.; Green, P.E. Psychometric methods in marketing research: Part II, multidimensional scaling. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Grunert, S.C. Measuring subjective meaning structures by the laddering method: Theoretical considerations and methodological problems. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. J. Mark. 1982, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.R.; Loken, B.; Kim, K.; Monga, A.B. Brand concept maps: A methodology for identifying brand association networks. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittka, O.; Sattler, H.; Zenker, S. Advanced brand concept maps: A new approach for evaluating the favorability of brand association networks. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M.I.M. Understanding Place Brands as Collective and Territorial Development Processes; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mainolfi, G.; De Nisco, A.; Marino, V.; Napolitano, M.R. Immagine Paese e Cultural Heritage. Proposta e Validazione di una Scala di Misura Formativa Della Cultural Heritage Image (CHEI). 2015. Available online: http://www.simktg.it/sp/call-for-paper-xii-convegno-sim.3sp (accessed on 3 July 2016).

- Future Brand Country Brand Index 2014–2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.futurebrand.com/futurebrand-country-index (accessed on 2 September 2016).

- Forester, J. Pianificazione e potere. In Pratiche e Teorie Interattive del Progetto Urbano; Edizioni Dedalo: Bari, Italy, 1998; Volume 184. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Londra, UK, 2013; ISBN 1412960991. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Experience Walkabout, Esplorazioni Partecipate. Available online: https://www.urbanexperience.it/walkabout/ (accessed on 10 August 2016).

- Careri, F. Walkscapes. Camminare Come Pratica Estetica; Einaudi: Rome, Italy, 2006; Volume 310. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Experiences Walkabout “I Luoghi di Zonzo. Primo episodio” a Pisticci. Available online: https://www.urbanexperience.it/eventi/walkabout-luoghi-zonzo-primo-episodio-pisticci/ (accessed on 10 August 2016).

- Bolognini, M. Democrazia Elettronica: Metodo Delphi e Politiche Pubbliche; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pacinelli, A. Metodi per la Ricerca Sociale Partecipata; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2008; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- World Café Community World Cafè Method. Available online: http://www.theworldcafe.com/key-concepts-resources/world-cafe-method/ (accessed on 12 October 2016).

- Osterwalder, A. The Business Model Ontology: A Proposition in a Design Science Approach; University of Lausanne: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal, B. Visual PROMETHEE 1.4 Manual. 2013. Available online: http://www.promethee-gaia.net/files/VPManual.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- Place Brand Observer Place Brand Knowledge Hub. 2016. Available online: https://placebrandobserver.com/place-branding-explained/ (accessed on 12 April 2016).

- Proctor, W.; Drechsler, M. Deliberative multicriteria evaluation. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2006, 24, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banville, C.; Landry, M.; Martel, J.; Boulaire, C. A stakeholder approach to MCDA. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 1998, 15, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvaresi, C. Community Hub, Due o Tre Cose Che so di Loro. 2016. Available online: https://www.che-fare.com/community-hub-due-o-tre-cose-che-so-di-loro/ (accessed on 8 October 2016).

- Perulli, P. The Urban Contract: Community, Governance and Capitalism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 1317037367. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Indicator Framework on Culture and Democracy—Policy Maker’s Guidebook; Council of Europe: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AUDIS Linee Guida per la Rigenerazione Urbana. 2014. Available online: http://audis.it/home (accessed on 15 December 2015).

- Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. The PROMETHEE methods for MCDM; the PROMCALC, GAIA and BANKADVISER software. In Readings in Multiple Criteria Decision Aid; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; pp. 216–252. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchini, E.E.; Pazzola, G. Torino Creativa. I Centri Indipendenti Culturali sul Territorio Torinese; Edizioni GAI: Turin, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Unioncamere-Fondazione Symbola Io sono Cultura—2016. L’Italia della qualità e della bellezza sfida la crisi. 2016. Available online: https://www.symbola.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Slide-presentazione_io-sono-cultura_1466676130-1.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2016).

- Buzan, T.; Buzan, B. The Mind Map Book: How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain\’s Untapped Potential; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Faro, 2005; Council of Europe: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Inglese, P.; Manzi, M.L. A multi-methodological decision-making process for cultural landscapes evaluation: The green lucania project. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, G. Social multi-criteria evaluation: Methodological foundations and operational consequences. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 158, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J. The elusive destination brand and the ATLAS wheel of place brand management. J. Travel Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le Valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Città e del Territorio; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 1997; Volume 74. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tricarico, L.; Jones, Z.M.; Daldanise, G. Platform Spaces: When culture and the arts intersect territorial development and social innovation, a view from the Italian context. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerreta, M.; Giovene di Girasole, E.; Poli, G.; Regalbuto, S. Operationalizing the Circular City Model for Naples’ City-Port: A Hybrid Development Strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiential Variables | Alternative Territorial Vocations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1: hospitality and resilient community | V2: the sacred and the profane | V3: agricultural tradition | V4: artisan and creative density | V5: landscape and biodiversity | |

| Regeneration of the material and immaterial heritage | Regeneration of the 6 public lammie (urban center) | Regeneration of ancient churches and buildings | Regeneration of the 6 public lammie for agricultural usage | Regeneration of the 6 public lammie for artisan and artistic activities | Creation of an environmental education center (CEA) |

| Increase of commercial structures for tourist hospitality | Increase of commercial structures | Increase of commercial structures for local economy | Regeneration of 5 private lammie for hospitality purposes | Increase of commercial structures in symbolic landscapes | |

| Realization of hospitality exchange services (couch surfing) for the private lammie | Creation of a crowdfunding platform for the recovery of lammie | Regeneration of public spaces with events at different times of the year | Creation of a collaborative crowdfunding platform for recovery and temporary rent of the lammie | Coordinated planning of workshops and researches for the discovery and recovery of the tangible and intangible landscape | |

| Coordinated program of the Pisticci tourist office | Promotion of Pacchiana stories, banditry, short stories about San Rocco and others | Construction of a communication strategy | Construction of the archaeo-museum school “The Painter from Pisticci” | Digital archive processing of natural and architectural heritage | |

| Calendar for seasonal thematic walk-about (P-stories) | Calendar for thematic seasonal walkabout calendar | Creation of multimedia peasant historical archive | Creation of multimedia historical archives (Lucania Film Festival) | Promotion of symbolic online actions to communicate the variety of landscapes | |

| Digital platform | Creation of a community tourism platform | Digitization of hidden cults and traditions | Digitization of the texts of peasant history | Collaborative platform for temporary rent of the lammie | Collaborative platform for knowledge exchange |

| Services for citizens and temporary residents | Increase of road transport lines for tourists | Increase of road transport lines for events and exhibitions | Increase of means of freight transport for the network | Implementation of theatrical experiments (Teatro dei Calanchi) | Increase of rail transport lines based on the planning |

| Creation of car sharing provider for Pisticci | Construction of thematic maps for accessibility to historical/religious buildings | Construction of thematic maps for agricultural products | Increase of road transport lines for events | Creation of car-sharing provider for visitors of Pisticci | |

| Urban contract | Construction of Pisticci Sustainable Urban Lab (PLUS) network between community groups, the Municipality and the “Local development agency” (APT) | Strengthening of the production cooperative network, associations (e.g., ass. Feste San Rocco), Ministero Beni Culturali and Pisticci Municipality for heritage revitalization | Creation of a collaborative platform between “Local action group” (GAL Basilicata), APT, local tourist office, local dealers and producers for temporary estate rent | Establishment of partnership “Municipality and Foundation Matera 2019” (social contract) —GAL COSVEL and enterprises, associations and creatives | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daldanise, G. From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410399

Daldanise G. From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410399

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaldanise, Gaia. 2020. "From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410399

APA StyleDaldanise, G. (2020). From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement. Sustainability, 12(24), 10399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410399