Meanings and Motives for Consumers’ Sustainable Actions in the Food and Clothing Domains

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Prior Literature and Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability Understanding

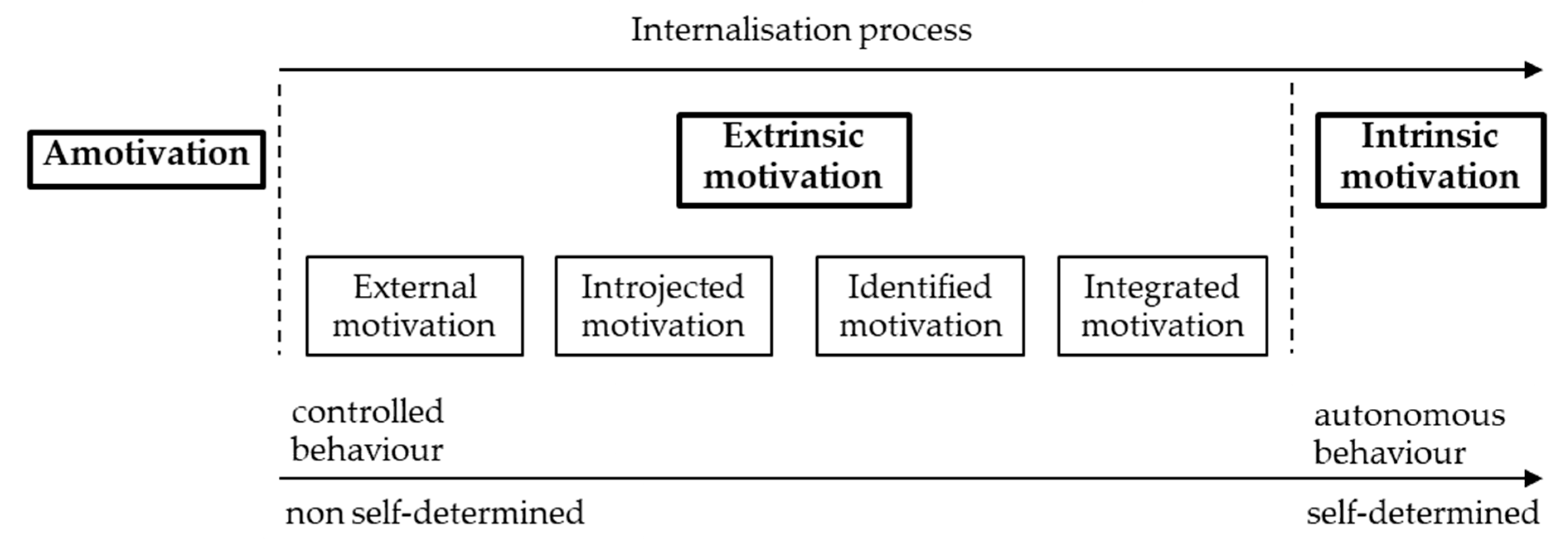

2.2. Motivation for Sustainable Actions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Interviewees and Recruitment

3.2. Interview Guide

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Consumer Associations with the Concept of Sustainability in General

4.2. Consumer Associations with the Concept of Sustainability in Food and Clothing

4.3. Behaviours Linked to Sustainability in Food and Apparel

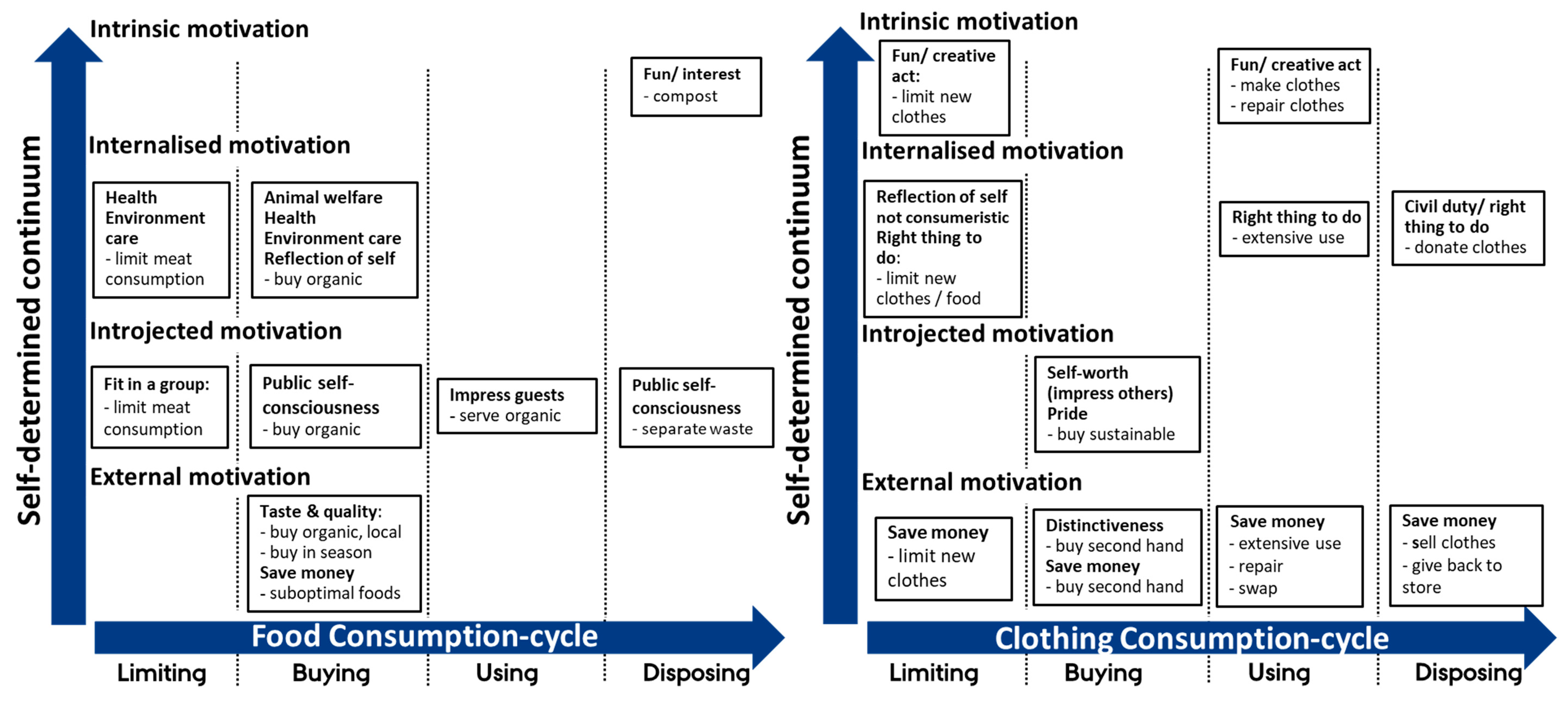

4.4. Motivations behind Sustainable Actions in the Apparel and Food Domains

4.4.1. Motivations that Drive Sustainable Behaviours in the Food Domain

4.4.2. Motivations that Drive Sustainable Behaviours in the Clothing Domain

4.4.3. Amotivation in Food and Clothing

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Future Research

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Implications for Public Policy and Marketing

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

Appendix B. Consumer Associations with Sustainability and Its Associated Importance in Consumers’ Minds

| Description (Code) | Number of Persons (Sustainability Meaning/Importance) | Theme | Quote Example from Interviewees |

| Resources (EN1) | 18/9 | Environment | “I get concerned when I see how much we dig out of the Earth, how many trees were cut down, how we pollute our water, it seems like it’s a never ending story about just taking stuff from nature without giving anything back and never replacing it with something good” |

| Environment (EN2) | 5/3 | Environment | “The main thing that comes to mind with regards to sustainability is definitely the environment and the planet” |

| Environment protection (EN3) | 15/2 | Environment | “I am just thinking about sustainable living so sustainability (is) something where you take care of the environment and your surroundings” |

| Production process (EN4) | 11/2 | Environment | “avoid doing permanent damage to the soil or the water or the fish or the animal population or everything there is” or “not use too many or any chemicals” |

| Carbon footprint (EN5) | 3 | Environment | “I think the first thing I think about is in terms of carbon footprint (…) and the ecosystem” |

| Circular economy (EN6) | 2 | Environment | “Circular economy like the native Americans they had this nature philosophy. If you take something from Earth you have to give it back, you cannot take more than we actually have; (…) we have to find a way to give back, so future generations can also leave from that.” |

| Worker wellbeing (S1) | 3 | Social | “I think when you are purchasing whatever product … as consumer you are more critical about how, or under what circumstances has this been produced and are there any children working there, or what is the environment for the workers like?” |

| Human rights (S2) | 2 | Social | |

| Child labour (S3) | 1 | Social | |

| Political (S4) | 4/1 | Social | |

| Economic growth (E1) | 1 | Economic | “I have this broad understanding of sustainability. It is also about economic and social sustainability, but I think it has its foundation in the environmental part so if we want to create a wealthy society we have to do it from a green perspective, from an environmentally-friendly perspective and the same goes for the social sustainability” |

| Future generations (T1) | 9/12 | Temporal | “Passing on the Earth and the planet to the future generations so that they can also be here and have high living standards and sustain themselves.” “I also think about the word long-term as opposed to short term, I think it’s inherited in the word (i.e., sustainability).” |

| Long term/long-lasting (T2) | 5 | Temporal | |

| Sceptic (P1) | 2 | Personal | “Mostly is a buzz world. It is some sort of a marketing trick most of the time. Because it is so broad it can mean a lot of things and sometimes it is just used to make me buy the product.” “I eat a lot of ecological things for example so it is, I just kind of thing that is also good for the body and for that part.” |

| Health (P2) | 2/3 | Personal | |

| Efficiency (Th1) | 1 | Technology | “I think it is also related to human interacting with technology and technological products. That is what I meant by long term.” |

| Technology (Th1) | 1 | Technology | |

| Restrictive behaviours | 14 | Behaviour | “I think about [i.e., sustainability], I always bring a tote bag, I don’t use plastic bags.”; “think about your choices not to use too much meat, not to eat too much meat.” |

| Purchase behaviours | 9 | Behaviour | “I also attempt to buy a bit more organic products that are made from recyclable materials”; “(…) something like for example … things are produced in the right way or maybe locally.”;”(…) buying used clothes.” |

| Using to prolong life of products | 5/1 | Behaviour | “reuse old stuff don’t throw that much out, don’t buy new electronics all the time.”;“(…) if I use a lot of… you know like a plastic dish or plate and just throwing it out instead of using something that I can use again.” |

| Disposal/Recycling | 10/1 | Behaviour | “(…) maybe that you recycle things for example like everyday things.”; “(…) thinking about your behaviour and not just throwing stuff that can be recycled away.” |

| Solution for current problems | /6 | - | “if we want to continue living on this planet, we want to continue to live on this planet I think it’s very important to deal with environmental problems” |

| Broad term | 7 | - | “it is so broad so it is difficult to say exactly what it is”; “It could be many things, it’s quite a broad term” |

References

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlek, C.; Steg, L. Human Behavior and Environmental Sustainability: Problems, Driving Forces, and Research Topics. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koger, S.M.; Winter, D.D. The Psychology of Environmental Problems: Psychology for Sustainability; Psychology Press Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our common future-Call for action. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R.E. Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. Handb. Environ. Sociol. 2002, 3, 482–524. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Europe’s Energy Transition Is Well Underway; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2017/TheSustainableDevelopmentGoalsReport2017.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- McKinsey. Sustainability’s Strategic Worth McKinsey Global Survey Results; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, B.J.K.; Radford, S.K. Consumer Perceptions of Sustainability: A Free Elicitation Study. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2012, 24, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.T.; Lee, H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F. Dissonance in students’ perceptions of sustainable development and sustainability: Implications for curriculum change. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 2007, 8, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanss, D.; Böhm, G. Sustainability seen from the perspective of consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzarini, G.A.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. Our own country is best: Factors influencing consumers’ sustainability perceptions of plant-based foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 60, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, E.L. Consumers interpreting sustainability: moving beyond food to fashion. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 1162–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; Declerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.L.; Kinley, T.R. Green spirit: consumer empathies for green apparel. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J.; Kanakaratne, M.D.S. The mindful consumer: Balancing egoistic and altruistic motivations to purchase local food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Egea, J.M.; De Frutos, N.G. Toward Consumption Reduction: An Environmentally Motivated Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I.R.; Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Abrahamse, W. Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, Norms, and Intrinsic Motivation to Act Proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnaghten, P. Public Perceptions and Sustainability in Lancashire. Indicators, Institutions, Participation. A report by the Centre for the Study of Environmental Change; Lancashire County Council: Preston, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, B.; Rodrigues, H.; Nogueira, R.M.; Guimarães, K.R.L.S.L.D.Q.; Behrens, J.H. What about sustainability? Understanding consumers’ conceptual representations through free word association. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 44, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloviita, A. Consumers’ Sustainability Perceptions of the Supply Chain of Locally Produced Food. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1492–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peano, C.; Merlino, V.M.; Sottile, F.; Borra, D.; Massaglia, S. Sustainability for Food Consumers: Which Perception? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J.; Banning, J. Addressing Sustainable Apparel Design Challenges With Problem-Based Learning. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada, M.; Garrido, M.V.; Rodrigues, D.L. Lost in processing? Perceived healthfulness, taste and caloric content of whole and processed organic food. Appetite 2017, 114, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.C.; Liu, Y. Are beliefs stronger than taste? A field experiment on organic and local apples. Food Qual. Preference 2017, 61, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P.; Haga, A.; Langeborg, L.; Holmgren, M.; Wallinder, M.; Nöstl, A.; Seager, P.B.; Marsh, J.E. The green halo: Mechanisms and limits of the eco-label effect. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova, B.; Vauclair, C.-M.; Kervyn, N.; Schumann, S.; Wood, R.; Klein, O. Savouring morality. Moral satisfaction renders food of ethical origin subjectively tastier. Appetite 2015, 91, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerding, S.G.; Schaffmann, A.-L.; Lehberger, M. Consumer Preferences for Different Designs of Carbon Footprint Labelling on Tomatoes in Germany—Does Design Matter? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.A. Utility of No Sweat Labels for Apparel Consumers: Profiling Label Users and Predicting Their Purchases. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, L.; Matthews, D. Consumer decision making when purchasing eco-friendly apparel. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: Literature overview. Econ. Altern. 2016, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asioli, D.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Sustainability-Related Food Labels. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D. Identity-based motivation: Implications for action-readiness, procedural-readiness, and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Bamossy, G.; Askegaard, S. Consumer Behavior; PrenticeHall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Cherry, M.; Watkins, M. Moral, Wasteful, Frugal, or Thrifty? Identifying Consumer Identities to Understand and Manage Pro-Environmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2017, 51, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Tuson, K.M.; Green-Demers, I.; Noels, K.; Beaton, A.M. Why Are You Doing Things for the Environment? The Motivation Toward the Environment Scale (MTES)1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacorta, M.; Koestner, R.; Lekes, N. Further Validation of the Motivation Toward the Environment Scale. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G. 10: A Motivational Analysis of Self-Determination for Pro-Environmental Behaviors. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Press Rochester: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, R. Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key Methods Geogr. 2003, 3, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bucic, T.; Harris, J.; Arli, D.I. Ethical Consumers among the Millennials: A Cross-National Study. J. Bus. Ethic 2012, 110, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I.; Van Steenburg, E. Me first, then the environment: young Millennials as green consumers. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Townsend, K. Reporting and Justifying the Number of Interview Participants in Organization and Workplace Research. Br. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazak, S.; Quoquab, F. Exploring Consumers’ Motivations for Sustainable Consumption: A Self-Deterministic Approach. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2017, 30, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete, L.; Castaño, R.; Felix, R.; Centeno, E.; González, E. Green consumer behavior in an emerging economy: confusion, credibility, and compatibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J.; Pesonen, S. Narratives of sustainable ways of living: constructing the self and the other as a green consumer. Manag. Decis. 2002, 40, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graebner, M.E.; Martin, J.A.; Roundy, P.T. Qualitative data: Cooking without a recipe. Strat. Organ. 2012, 10, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C.; Patrick, H.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and physical activity: The dynamics of motivation in development and wellness. Hellenic Journal of Psychology. 2009, 6, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Catlin, J.R.; Luchs, M.G.; Phipps, M. Consumer Perceptions of the Social Vs. Environmental Dimensions of Sustainability. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwozdz, W.; Netter, S.; Bjartmarz, T.; Reisch, L.A. Survey Results on Fashion Consumption and Sustainability among Young Swedes; Report Mistra Future Fashion; Mistra Future Fashion: Borås, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Manik, J.A.; Greenhouse, S.; Yardley, J. Western Firms Feel Pressure As Toll Rises in Bangladesh. New York Times. 25 April 2013. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/26/world/asia/bangladeshi-collapse-kills-many-garment-workers.html?smid=pl-share (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Ritch, E.L. Extending sustainability from food to fashion consumption: the lived experience of working mothers. Int. J. Manag. Cases 2014, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peattie, K.; Collins, A. Guest editorial: perspectives on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickenbrok, C.; Martinez, L.F. Communicating green fashion across different cultures and geographical regions. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2018, 15, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, N.D. The Branding of Ethical Fashion and the Consumer: A Luxury Niche or Mass-market Reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Half of Spending on Housing, Transport and Food. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/WDN-20190703-1 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a Measure of the Motives Underlying the Selection of Food: the Food Choice Questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, N.M.; Pelletier, L.G.; Baxter, D.E. Doing the Difficult Stuff: Influence of Self-Determined Motivation Toward the Environment on Transportation Proenvironmental Behavior. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. Follow the signal: When past pro-environmental actions signal who you are. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeroff, C.; Rozin, P. The Contagion Concept in Adult Thinking in the United States: Transmission of Germs and of Interpersonal Influence. Ethos 1994, 22, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Why young people do things for the environment: The role of parenting for adolescents’ motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, W.; Pauw, J.; Donche, V.; Petegem, P. “Why (Should) I Do Something for the Environment?” Profiles of Flemish Adolescents’ Motivation Toward the Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green-Demers, I.; Pelletier, L.G.; Ménard, S. The impact of behavioural difficulty on the saliency of the association between self-determined motivation and environmental behaviours. Can. J. Behav. Sci. / Rev. Can. des Sci. du Comport. 1997, 29, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.D.; Bhamra, T. Design for sustainable behaviour: a case study of using human-power as an everyday energy source. J. Design Res. 2016, 14, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Meaning Themes | Clothing | Frequency * | Food | Frequency * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | material type | 17 | resources | 6 |

| environmental impact | 13 | environmental impact | 9 | |

| production process | 21 | production process | 11 | |

| workers’ wellbeing | 17 | organic | 12 | |

| animal welfare | 8 | |||

| workers’ wellbeing | 4 | |||

| local | 11 | |||

| Use | repurposing | 3 | use leftovers | 7 |

| long-lasting | 18 | |||

| second-hand | 10 | |||

| prolonging life of clothes | 10 | |||

| Disposal | donating | 12 | reduce waste | 17 |

| store’s recycling program | 3 | |||

| waste of clothes/overproduction | 6 | |||

| Transport | carbon footprint | 10 | carbon footprint | 11 |

| Behaviour | avoid plastic wraps | 3 | avoid plastic wraps | 5 |

| labelled as sustainable (as a guide) | 3 | grow own food | 2 | |

| limit consumption | 3 | limit meat | 6 | |

| seasonality | 2 | |||

| Other | fuzzy term | 2 | taking care of own health | 9 |

| search for information | 4 |

| Behaviour Category | Apparel Domain | Food Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Purchasing | second-hand | box subscription |

| labelled clothes | single pieces of fruits | |

| long-lasting materials | ecological/organic | |

| close to expiration (suboptimal foods) | ||

| labelled products | ||

| local products | ||

| what is in season | ||

| Restrictive | limit purchases of clothes | avoid food waste (limit amount of food bought) |

| limit consumption of new clothes | limit meat consumption | |

| limit wash | hold back from impulse buying | |

| no softener | avoid products made of endangered species | |

| eco softeners and soaps | avoid palm oil | |

| avoid excess/unnecessary plastic packaging | ||

| Using | repair clothes | use leftovers |

| repurpose clothes | ||

| share/swap clothes | ||

| use clothes longer | ||

| Disposal | donate clothes | recycling |

| give clothes to recycling programme at store | composting | |

| sell clothes | ||

| Other | research before purchase | compare products before purchasing |

| make own clothes | research before purchase | |

| bring own bag | ||

| grow own food | ||

| take care of own health | ||

| make shopping list | ||

| learn from mistakes (food waste) | ||

| have a meal plan |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stancu, C.M.; Grønhøj, A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Meanings and Motives for Consumers’ Sustainable Actions in the Food and Clothing Domains. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410400

Stancu CM, Grønhøj A, Lähteenmäki L. Meanings and Motives for Consumers’ Sustainable Actions in the Food and Clothing Domains. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410400

Chicago/Turabian StyleStancu, Catalin M., Alice Grønhøj, and Liisa Lähteenmäki. 2020. "Meanings and Motives for Consumers’ Sustainable Actions in the Food and Clothing Domains" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410400

APA StyleStancu, C. M., Grønhøj, A., & Lähteenmäki, L. (2020). Meanings and Motives for Consumers’ Sustainable Actions in the Food and Clothing Domains. Sustainability, 12(24), 10400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410400