Linking Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing with Prosocial Organizational Behavior of Altruism and Civic Virtue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypotheses Development

2.1. Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing

2.2. Affective Commitment and Altruism via Knowledge Sharing Behavior

2.3. Affective Commitment and Civic Virtue via Knowledge Sharing Behavior

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

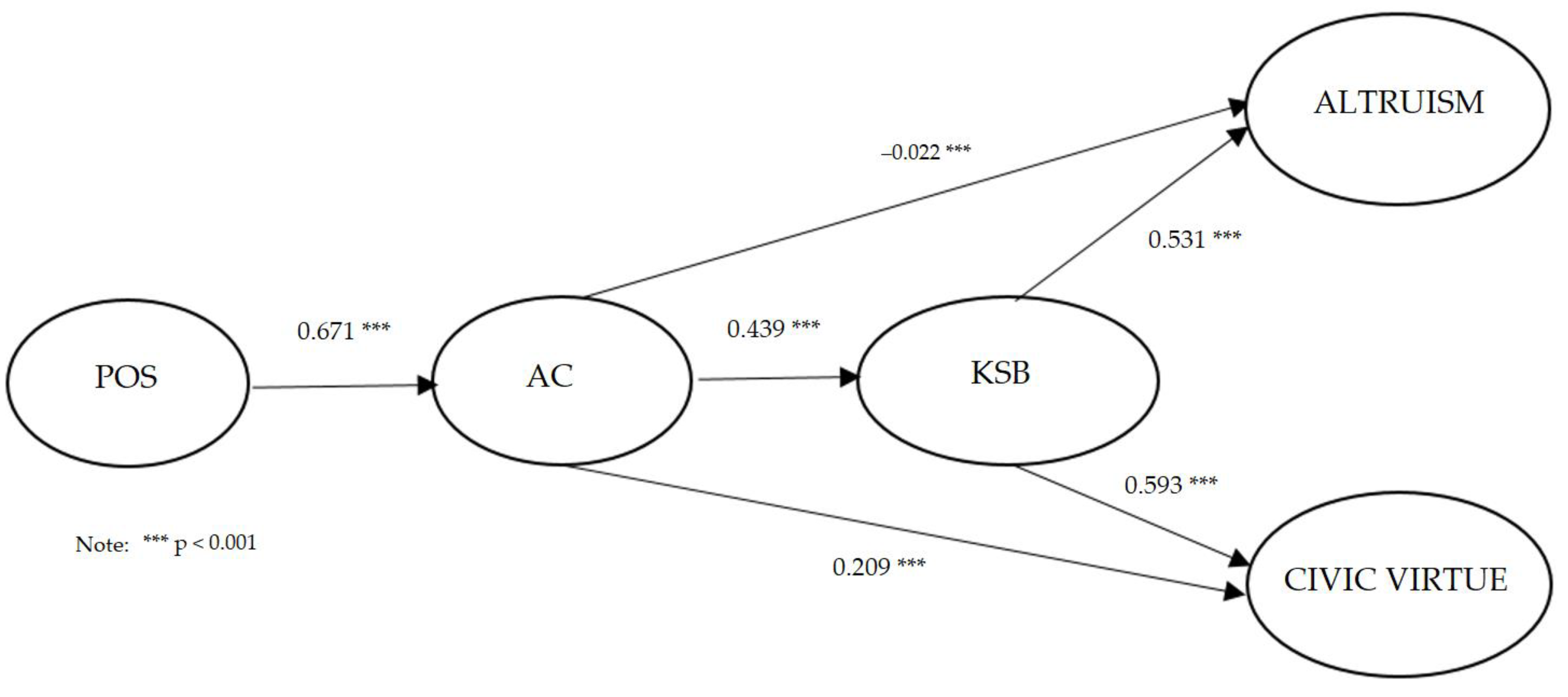

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Key Findings

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polese, F.; Carrubbo, L.; Caputo, F.; Sarno, D. Managing healthcare service ecosystems: Abstracting a sustainability-based view from hospitalization at home (HaH) practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Yu, Y. The influence of perceived corporate sustainability practices on employees and organizational performance. Sustainability 2014, 6, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Carrion, R.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Developing a sustainable HRM system from a contextual perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Coetzer, A. Institutional Environment, Managerial Attitudes and Environmental Sustainability Orientation of Small Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Buhnova, B.; Walletzký, L. Investigating the role of smartness for sustainability: Insights from the Smart Grid domain. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillo, V.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Ardito, L.; Del Giudice, M. Understanding sustainable innovation: A systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, P.K.; Hall, P.; Soskice, D. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugueró-Escofet, N.; Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Sustainable human resource management: How to create a knowledge sharing behavior through organizational justice, organizational support, satisfaction and commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.; Geissler, B.; Schreder, G.; Zenk, L. Living sustainability, or merely pretending? From explicit self-report measures to implicit cognition. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosek, B.A.; Hawkins, C.B.; Frazier, R.S. Implicit social cognition: From measures to mechanisms. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Motowidlo, S.J. Prosocial Organizational Behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Zelli, A.; Capanna, C. A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial Behavior: Multilevel Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2005, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J. Willingness and capacity: The determinants of prosocial organizational behaviour among nurses in the UK. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Grant, A.M. The Bright Side of Being Prosocial at Work, and the Dark Side, Too: A Review and Agenda for Research on Other-Oriented Motives, Behavior, and Impact in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 599–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.P.; Tian, X.Z.; Guo, X.D. Prosocial Behavior in Organizations: A Literature Review and Prospects. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2019, 41, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, J.B. Antecedents and consequences of employee volunteerism. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. A Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2011, 71, 2957. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M.; Fay, D. 4. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 133–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P. To share or not to share: Modeling knowledge sharing using exchange ideology as a moderator. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, O.C.; Sofian, S. Individual Factors and Work Outcomes of Employee Engagement. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, S.M.; Penner, L.A. The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: A motivational analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, M.A. Dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior: Motives, motive fulfillmen and role identity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2006, 34, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Maynes, T.D.; Spoelma, T.M. Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Issues in Organization and Management Series; Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-669-11788-9. (Hardcover). [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, S.; Bartolomucci, N.; Beaumier, E.; Boulanger, J.; Corrigan, R.; Doré, I.; Girard, C.; Serroni, C. Organizational citizenship behavior: A case study of culture, leadership and trust. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; SAGE Publications Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781452231082. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Allyn Piliavin, J.; Schroeder, D.A.; Penner, L.A. The Social Psychology of Prosocial Behavior—Chapter 8. In The Social Psychology of Prosocial Behavior; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 268–307. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, V.I.; Borman, W.C. Investigating the Underlying Structure of the Citizenship Performance Domain. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2000, 10, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. Impact of perceived organisational support on organisational citizenship behaviour on health care and cure professionals. Manag. Dyn. 2019, 19, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Leiter, M. The mediating effect of burnout on the relationship between structural empowerment and organizational citizenship behaviours. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. The effects of emotional intelligence on counterproductive work behaviors and organizational citizen behaviors among food and beverage employees in a deluxe hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.H.; Han, T.S.; Chuang, J.S. The relationship between high-commitment HRM and knowledge-sharing behavior and its mediators. Int. J. Manpow. 2011, 32, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, C.W.; Yoon, H.J.; Choi, M. Exploring the affective mechanism linking perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing intention: A moderated mediation model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D.M.; Shipp, A.J.; Rosen, B.; Furst, S.A. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Career Outcomes: The Cost of Being a Good Citizen. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 958–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Hsiung, H.H.; Harvey, J.; LePine, J.A. “Well, i’m tired of tryin’!” organizational citizenship behavior and citizenship fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.; Chatman, J. Organizational Commitment and Psychological Attachment. The Effects of Compliance, Identification, and Internalization on Prosocial Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.; Steers, R.M. Employe-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism & Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 49, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived Organizational Support: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; McEvily, B.; Reagans, R. Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M. A model of knowledge-sharing motivation. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hooff, B.; Ridder, J.A. Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.F.; Cabrera, A. Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanock, L.R.; Eisenberger, R. When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor aupport, perceived organizational support, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Kevin Kelloway, E. Predictors of employees’ perceptions of knowledge sharing cultures. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2003, 24, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Barling, J. Knowledge work as organizational behavior. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2000, 2, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaas, B.S.; Olson-Buchanan, J.B.; Ward, A.K. The determinants of alternative forms of workplace voice: An integrative perspective. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 314–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, A.C.; Bolino, M.C.; Song, H.; Stornelli, J. Examining the nature, causes, and consequences of profiles of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived Organizational Support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, B. Direct and interactive effects of perceived organizational support and positive reciprocity beliefs on organizational identification: An empirical study. In Innovation, Technology, and Market Ecosystems: Managing Industrial Growth in Emerging Markets; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 187–202. ISBN 9783030230104. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Hooff, B.; de Leeuw van Weenen, F. Committed to share: Commitment and CMC use as antecedents of knowledge sharing. Knowl. Process Manag. 2004, 11, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: An empirical study. Int. J. Manpow. 2007, 28, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, M. The roles of power distance orientation and perceived insider status in the subordinates’ Moqi with supervisors and sustainable knowledge-sharing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. J. Inf. Sci. 2007, 33, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Kärreman, D. Odd couple: Making sense of the curious concept of knowledge management. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 995–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangaraja, G.; Rasdi, R.M.; Ismail, M.; Samah, B.A. Fostering knowledge sharing behavior among public sector managers: A proposed model for the Malaysian public service. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Yoon, D.Y.; Suh, B.; Li, B.; Chae, C. Organizational support on knowledge sharing: A moderated mediation model of job characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, Z.Y.; Fang, C.H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. Commitment before and after: An evaluation and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wong, C. keung Understanding organizational citizenship behavior from a cultural perspective: An empirical study within the context of hotels in Mainland China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Affective organizational commitment and citizenship behavior: Linear and non-linear moderating effects of organizational tenure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaiean, A.; Esmaeili Givi, M.; Givi, H.E.; Nasrabadi, M.B. The Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment, Satisfaction and Trust. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cohen, A.; Liu, Y. Relationships between in-role performance and individual values, commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior among Israeli teachers. Int. J. Psychol. 2011, 46, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grego-Planer, D. The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors in the public and private sectors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, H.; Bamel, U.; Ashta, A.; Stokes, P. Examining an integrative model of resilience, subjective well-being and commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviours. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 1274–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Workman, K.M.; Hardin, A.E. Compassion at Work. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.Y.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zu’bi, H.A. Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Impacts on Knowledge Sharing: An Empirical Study. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D. Linking human resource management and knowledge management via commitment: A review and research agenda. Empl. Relations 2003, 25, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.J.; Liao, S.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lo, W.P. Organizational commitment, knowledge sharing and organizational citizenship behaviour: The case of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2015, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D. Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review. J. Conflict Resolut. 2010, 54, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, D.G.; Nowak, M.A.; Fowler, J.H.; Christakis, N.A. Static network structure can stabilize human cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17093–17098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.N. Work Groups, Structural Diversity, and Knowledge Sharing in a Global Organization. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. The nature of human altruism. Nature 2003, 425, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S.; Fehr, E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 2001, 71, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, M.H.; Nojabaee, S.S.; Arjmand, F. The relationship between the organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior of the employees. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 10, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, J.Y.; Gardner, W.L. Handbook of Motivation Science; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 1-59385-568-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tansky, J.W. Justice and organizational citizenship behavior: What is the relationship? Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1993, 6, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, B.L.; Meglino, B.M. The Role of Dispositional and Situational Antecedents in Prosocial Organizational Behavior: An Examination of the Intended Beneficiaries of Prosocial Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, D. Social networks, the tertius iungens orientation, and involvement in innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 100–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.Y.; DeSteno, D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, F.J.; Reagans, R.E.; Amanatullah, E.T.; Ames, D.R. Helping one’s way to the top: Self-monitors achieve status by helping others and knowing who helps whom. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Does Intrinsic Motivation Fuel the Prosocial Fire? Motivational Synergy in Predicting Persistence, Performance, and Productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Ryan, K. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Tang, R.L. Effects of psychological contract breach on performance of IT employees: The mediating role of affective commitment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2006, 79, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V. Exploring civic virtue and turnover intention during organizational changes. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayas-Ortiz, M.; Rosario, E.; Marquez, E.; Gruñeiro, P.C. Relationship between organizational commitments and organizational citizenship behaviour in a sample of private banking employees. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2015, 35, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J. (Annette); Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Li, Y. How to fuel employees’ prosocial behavior in the hotel service encounter. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F.N. Research of Behaviour: Research Methods in Social Sciences; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Science, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; Volume 3, ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Companies Corporate: New York City, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 3, ISBN1 007047849X. ISBN2 9780070478497. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; Graham, J.W.; Dienesch, R.M. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Construct Redefinition, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 765–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Roldán, J.L.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781466601796. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1452217440. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; ISBN1 0962262846. ISBN2 9780962262845. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions (With Discussion). J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1976, 38, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.W.; Van Dyne, L. Gathering information and exercising influence: Two forms of civic virtue organizational citizenship behavior. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2006, 18, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wombacher, J.C.; Felfe, J. Dual commitment in the organization: Effects of the interplay of team and organizational commitment on employee citizenship behavior, efficacy beliefs, and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, K.; Michailova, S. Diagnosing and fighting knowledge-sharing hostility. Organ. Dyn. 2002, 31, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D.; Bosua, R.; Helms, R. Knowledge Management in Organizations: A Critical Introduction, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bülbül, A. Social Work Design and Prosocial Organizational Behaviors. Univers. J. Psychol. 2014, 2, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, W.; Schmidt, B.; Sloep, P.; Drachsler, H. Knowledge worker roles and actions-results of two empirical studies. Knowl. Process Manag. 2011, 18, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekas, K.H.; Bauer, T.N.; Welle, B.; Kurkoski, J.; Sullivan, S. Organizational citizenship behavior, version 2.0: A review and qualitative investigation of ocbs for knowledge workers at google and beyond. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, T.G.; Lee, C.S.; Bourdage, J.S. Who helps and why? Contextualizing organizational citizenship behavior. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2019, 51, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Mayer, D.M. Good Soldiers and Good Actors: Prosocial and Impression Management Motives as Interactive Predictors of Affiliative Citizenship Behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De León, M.C.D.; Finkelstein, M. Comportamiento de ciudadanía organizacional y bienestar. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2016, 16, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Glomb, T.M.; Bhave, D.P.; Miner, A.G.; Wall, M. Doing good, feeling good: Examining the role of organizational citizenship behaviors in changing mood. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 191–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wat, D.; Shaffer, M.A. Equity and relationship quality influences on organizational citizenship behaviors: The mediating role of trust in the supervisor and empowerment. Pers. Rev. 2005, 34, 406–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.P.; Cross, R.; Levin, D.Z. Performance Benefits From Providing Assistance in Networks: Relationships That Generate Learning. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 412–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Reio, T.G. Career benefits associated with mentoring for mentors: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henttonen, K.; Kianto, A.; Ritala, P. Knowledge sharing and individual work performance: An empirical study of a public sector organisation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E.M.; Chang, C.H.; Miloslavic, S.A.; Johnson, R.E. Relationships of role stressors with organizational citizenship behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp Ellington, J.; Dierdorff, E.C.; Rubin, R.S. Decelerating the diminishing returns of citizenship on task performance: The role of social context and interpersonal skill. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stel, F. Does pro-social orientation matter? Effects of personality and cooperation styles on the performance of innovation teams. In Proceedings of the the 14th International Conference on Innovation and Management: Innovation on the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Swansea, UK, 21–22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, L.L.; Maynard, M.T.; Jones Young, N.C.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. Virtual Teams Research: 10 Years, 10 Themes, and 10 Opportunities. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1313–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogervorst, N.; De Cremer, D.; van Dijke, M.; Mayer, D.M. When do leaders sacrifice?. The effects of sense of power and belongingness on leader self-sacrifice. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 990–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; He, W. Corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct/Indicators | Loadings | Cronbach’s α | ρA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived organizational support (POS) | 0.896 | 0.899 | 0.919 | 0.618 | |

| POS1 | 0.763 | ||||

| POS2 | 0.749 | ||||

| POS4 | 0.836 | ||||

| POS5 | 0.774 | ||||

| POS6 | 0.829 | ||||

| POS7 | 0.803 | ||||

| POS8 | 0.742 | ||||

| Affective commitment (AC) | 0.895 | 0.905 | 0.920 | 0.657 | |

| AC1 | 0.709 | ||||

| AC2 | 0.755 | ||||

| AC3 | 0.878 | ||||

| AC4 | 0.796 | ||||

| AC5 | 0.874 | ||||

| AC7 | 0.839 | ||||

| Knowledge sharing behavior (KSB) | 0.879 | 0.883 | 0.906 | 0.579 | |

| KSB1 | 0.757 | ||||

| KSB2 | 0.753 | ||||

| KSB3 | 0.779 | ||||

| KSB4 | 0.788 | ||||

| KSB5 | 0.754 | ||||

| KSB6 | 0.710 | ||||

| KSB7 | 0.784 | ||||

| Altruism | 0.833 | 0.836 | 0.882 | 0.600 | |

| ALT1 | 0.772 | ||||

| ALT2 | 0.822 | ||||

| ALT3 | 0.704 | ||||

| ALT4 | 0.813 | ||||

| ALT5 | 0.757 | ||||

| Civic virtue | 0.794 | 0.795 | 0.866 | 0.619 | |

| CIVIR1 | 0.733 | ||||

| CIVIR2 | 0.787 | ||||

| CIVIR3 | 0.825 | ||||

| CIVIR4 | 0.800 |

| Item | Affective Commitment (AC) | Altruism | Civic Virtue | Knowledge Sharing Behavior (KSB) | Perceived Organizational Support (POS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT1 | 0.161 | 0.772 | 0.392 | 0.407 | 0.155 |

| ALT2 | 0.202 | 0.822 | 0.420 | 0.418 | 0.178 |

| ALT3 | 0.118 | 0.704 | 0.378 | 0.346 | 0.147 |

| ALT4 | 0.150 | 0.813 | 0.363 | 0.396 | 0.207 |

| ALT5 | 0.176 | 0.757 | 0.395 | 0.441 | 0.174 |

| CIVIR1 | 0.350 | 0.438 | 0.733 | 0.536 | 0.321 |

| CIVIR2 | 0.344 | 0.365 | 0.787 | 0.519 | 0.274 |

| CIVIR3 | 0.412 | 0.366 | 0.825 | 0.552 | 0.366 |

| CIVIR4 | 0.368 | 0.415 | 0.800 | 0.547 | 0.291 |

| AC1 | 0.709 | 0.084 | 0.246 | 0.216 | 0.405 |

| AC2 | 0.755 | 0.223 | 0.444 | 0.420 | 0.458 |

| AC3 | 0.878 | 0.154 | 0.407 | 0.371 | 0.559 |

| AC4 | 0.796 | 0.174 | 0.324 | 0.323 | 0.579 |

| AC5 | 0.874 | 0.152 | 0.371 | 0.345 | 0.610 |

| AC7 | 0.839 | 0.210 | 0.448 | 0.414 | 0.615 |

| KSB1 | 0.352 | 0.445 | 0.538 | 0.757 | 0.339 |

| KSB2 | 0.395 | 0.407 | 0.579 | 0.753 | 0.355 |

| KSB3 | 0.287 | 0.447 | 0.470 | 0.779 | 0.269 |

| KSB4 | 0.297 | 0.378 | 0.504 | 0.788 | 0.243 |

| KSB5 | 0.293 | 0.333 | 0.470 | 0.754 | 0.226 |

| KSB6 | 0.207 | 0.419 | 0.411 | 0.710 | 0.197 |

| KSB7 | 0.454 | 0.351 | 0.629 | 0.784 | 0.390 |

| POS1 | 0.532 | 0.297 | 0.442 | 0.430 | 0.763 |

| POS2 | 0.476 | −0.013 | 0.158 | 0.156 | 0.749 |

| POS4 | 0.579 | 0.269 | 0.347 | 0.343 | 0.836 |

| POS5 | 0.503 | 0.018 | 0.219 | 0.196 | 0.774 |

| POS6 | 0.567 | 0.284 | 0.371 | 0.380 | 0.829 |

| POS7 | 0.529 | 0.020 | 0.220 | 0.190 | 0.803 |

| POS8 | 0.496 | 0.316 | 0.421 | 0.420 | 0.742 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | Affective Commitment (AC) | Altruism | Civic Virtue | Knowledge Sharing Behavior (KSB) | Perceived Organizational Support (POS) |

| Affective commitment (AC) | 0.811 | ||||

| Altruism | 0.211 | 0.775 | |||

| Civic virtue | 0.469 | 0.503 | 0.787 | ||

| Knowledge sharing behavior (KSB) | 0.439 | 0.521 | 0.685 | 0.761 | |

| Perceived organizational support (POS) | 0.671 | 0.223 | 0.399 | 0.388 | 0.786 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio | Affective Commitment (AC) | Altruism | Civic Virtue | Knowledge Sharing Behavior (KSB) | Perceived Organizational Support (POS) |

| Affective commitment (AC) | |||||

| Altruism | 0.235 | ||||

| (0.182;0.289) | |||||

| Civic virtue | 0.546 | 0.620 | |||

| (0.497;0.591) | (0.565;0.669) | ||||

| Knowledge sharing behavior (KSB) | 0.474 | 0.607 | 0.809 | ||

| (0.428;0.519) | (0.556;0.654) | (0.777;0.836) | |||

| Perceived organizational support (POS) | 0.740 | 0.258 | 0.469 | 0.423 | |

| (0.710;0.767) | (0.210;0.284) | (0.422;0.513) | (0.378;0.464) |

| Endogenous Variable Structural Path | Direct Effect | t-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Explained Variance | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective commitment (AC) POS → AC (H1) (R2 = 0.450; Q2 = 0.291) | 0.671 | 40.248 *** | (0.643; 0.698) Sig. | 45% | 0.818 |

| Knowledge sharing behavior (KSB) AC → KSB (H2) (R2 = 0.192; Q2 = 0.107) | 0.439 | 17.79 *** | (0.398; 0.479) Sig. | 19.2% | 0.238 |

| Altruism AC →Altruism KSB → Altruism (R2 = 0.272; Q2 = 0.160) | −0.022 0.531 | 0.685 14.328 *** | (−0.075; 0.033) N.S. (0.466; 0.589) Sig. | 0% 27.2% | 0.001 0.313 |

| Civic virtue AC → Civic virtue KSB →Civic virtue (R2 = 0.504; Q2 = 0.309) | 0.209 0.593 | 8.464 *** 24.371 *** | (0.168; 0.250) Sig. (0.553; 0.632) Sig. | 9.8% 40.6% | 0.071 0.573 |

| Relationship | Indirect Effects | Standard Deviation | t Statistics | p Values | Bootstrapping 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS → AC → Altruism | −0.015 | 0.022 | 0.684 | 0.247 | (−0.050 | 0.022) |

| AC → KSB →Altruism (H4) | 0.232 | 0.019 | 12.271 | 0.000 | (0.202 | 0.264) |

| POS → AC → KSB → Altruism | 0.156 | 0.014 | 11.337 | 0.000 | (0.134 | 0.180) |

| POS → AC → Civic virtue | 0.140 | 0.017 | 8.143 | 0.000 | (0.112 | 0.169) |

| AC → KSB → Civic virtue (H5) | 0.260 | 0.016 | 16.56 | 0.000 | (0.235 | 0.286) |

| POS →AC → KSB → Civic virtue | 0.175 | 0.012 | 14.453 | 0.000 | (0.155 | 0.195) |

| POS → AC → KSB (H3) | 0.295 | 0.019 | 15.089 | 0.000 | (0.263 | 0.326) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Enache-Zegheru, M.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Linking Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing with Prosocial Organizational Behavior of Altruism and Civic Virtue. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410289

Ficapal-Cusí P, Enache-Zegheru M, Torrent-Sellens J. Linking Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing with Prosocial Organizational Behavior of Altruism and Civic Virtue. Sustainability. 2020; 12(24):10289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410289

Chicago/Turabian StyleFicapal-Cusí, Pilar, Mihaela Enache-Zegheru, and Joan Torrent-Sellens. 2020. "Linking Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing with Prosocial Organizational Behavior of Altruism and Civic Virtue" Sustainability 12, no. 24: 10289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410289

APA StyleFicapal-Cusí, P., Enache-Zegheru, M., & Torrent-Sellens, J. (2020). Linking Perceived Organizational Support, Affective Commitment, and Knowledge Sharing with Prosocial Organizational Behavior of Altruism and Civic Virtue. Sustainability, 12(24), 10289. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410289