Study Results

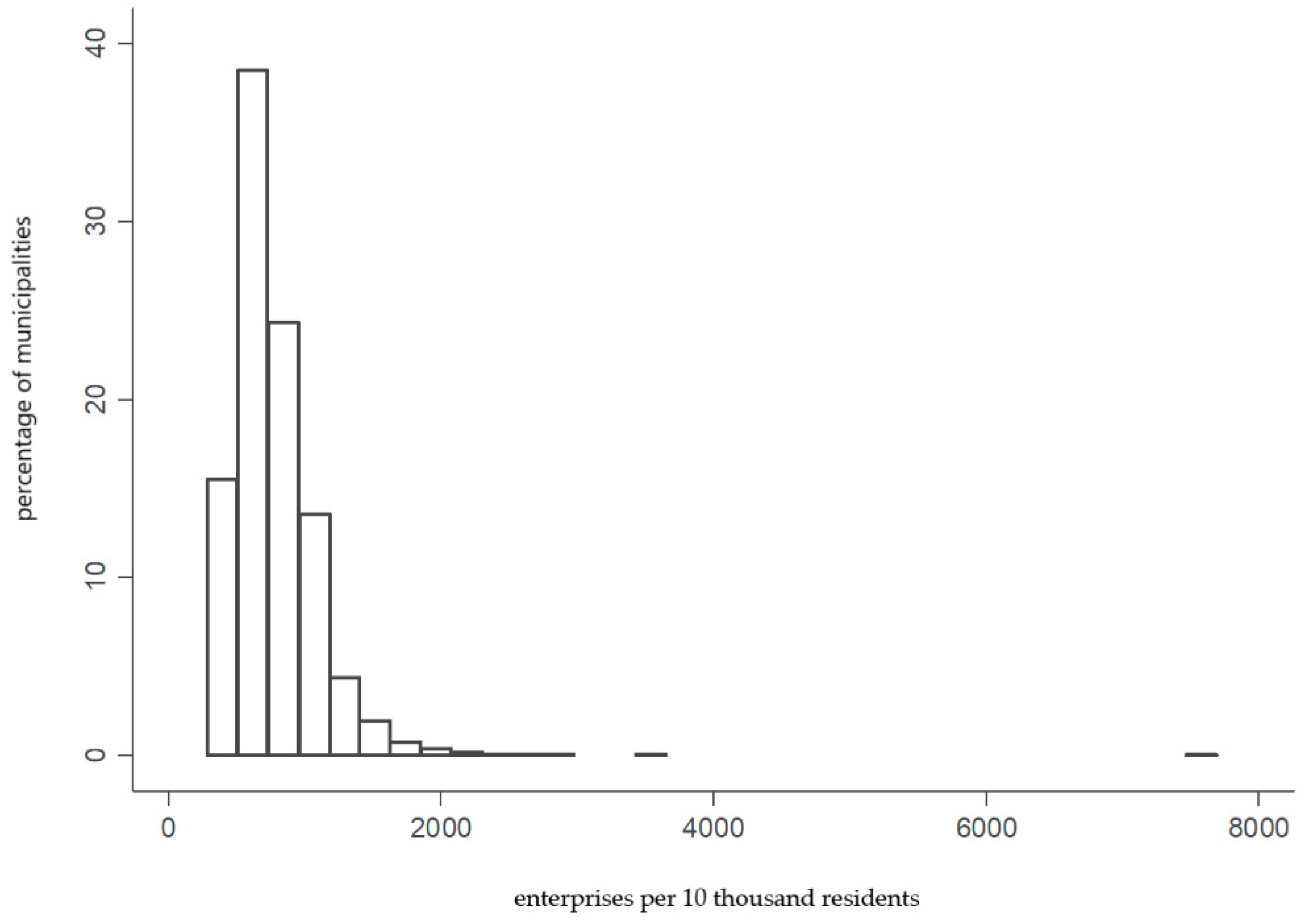

The distribution of the dependent variable is shown in

Figure 2 below, and

Table 1 shows its parameters.

Table 1 shows that the average number of enterprises (per ten thousand inhabitants) in Polish municipalities is 778. The Figure shows that the distribution of the dependent variable is strongly rightward: most of the observations (municipalities) are in the initial part of the distribution. For 2458 municipalities, i.e., 99% of the observations, the number of registered enterprises does not exceed 2 thousand per ten thousand inhabitants. At the same time, a small number of observations is far from the central value of the distribution. Extreme values in this range can be observed for the following municipalities (

Table 2 below):

The main atypical observations constitute the municipalities which are a strong brand as centres of mountain tourism (Karpacz, Zakopane) and coastal tourism (Mielno, Krynica Morska, Rewal, Łeba, Jastarnia, Międzyzdroje, Władysławowo). Another group is the municipalities which are part of an agglomeration—especially Warsaw and Poznań. Sopot and Podkowa Leśna are the municipalities which are both part of an agglomeration and have the highest percentage of people with higher education in Poland. The high score of Podkowa Leśna constitutes an interesting case. The town is distinguished by a very high level of entrepreneurship despite the lack of investment plots. Interviews conducted in Podkowa Leśna showed that the key skill of this municipality is attracting “valuable” residents. Many presidents of companies, actors and artists who identify themselves with this town live there and therefore pay taxes there. The example of Podkowa Leśna indicates that an important aspect of the analysis is the answer to the question: what determines the choice of the municipality to be inhabited by the most valuable settlers in terms of paying taxes?

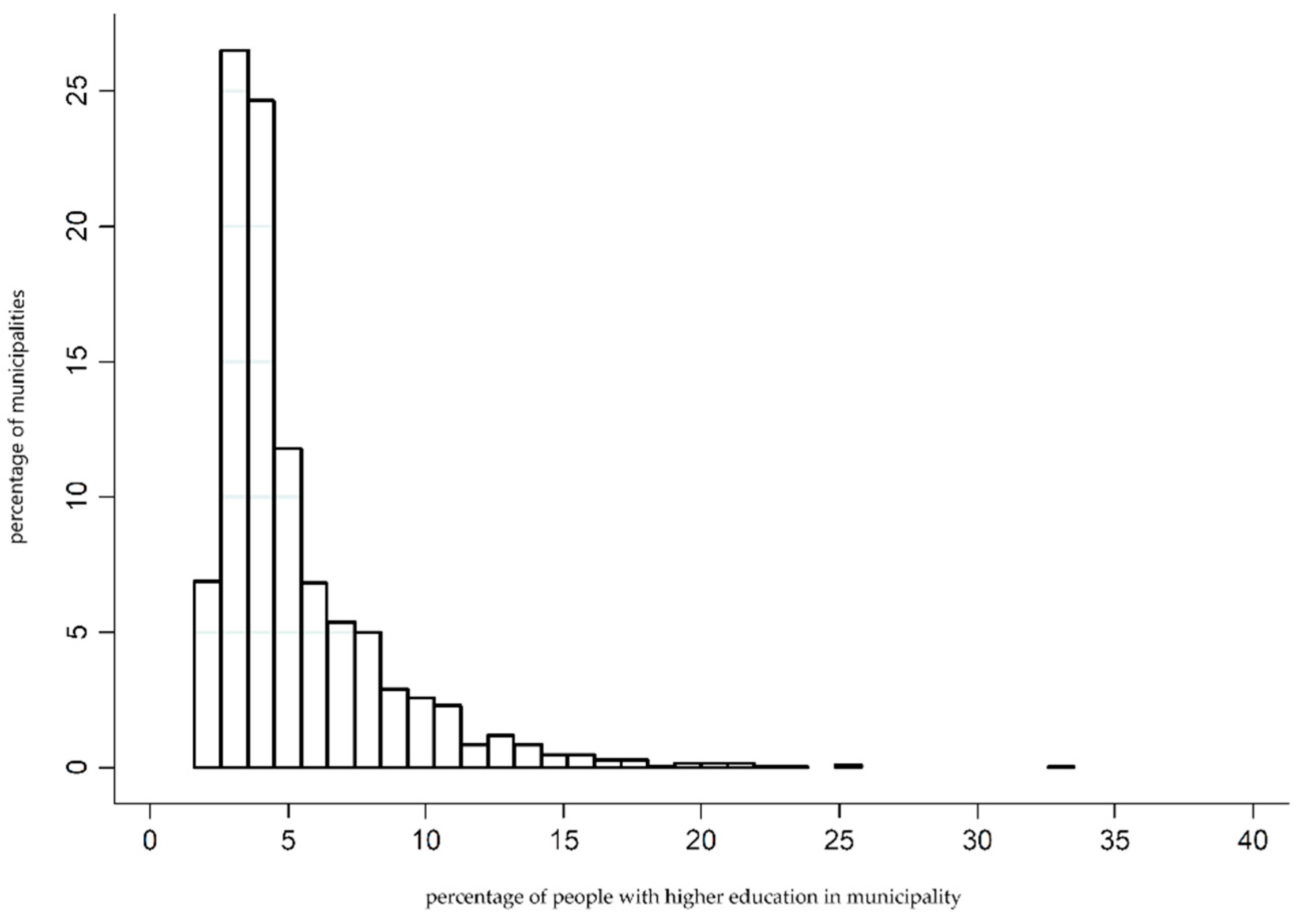

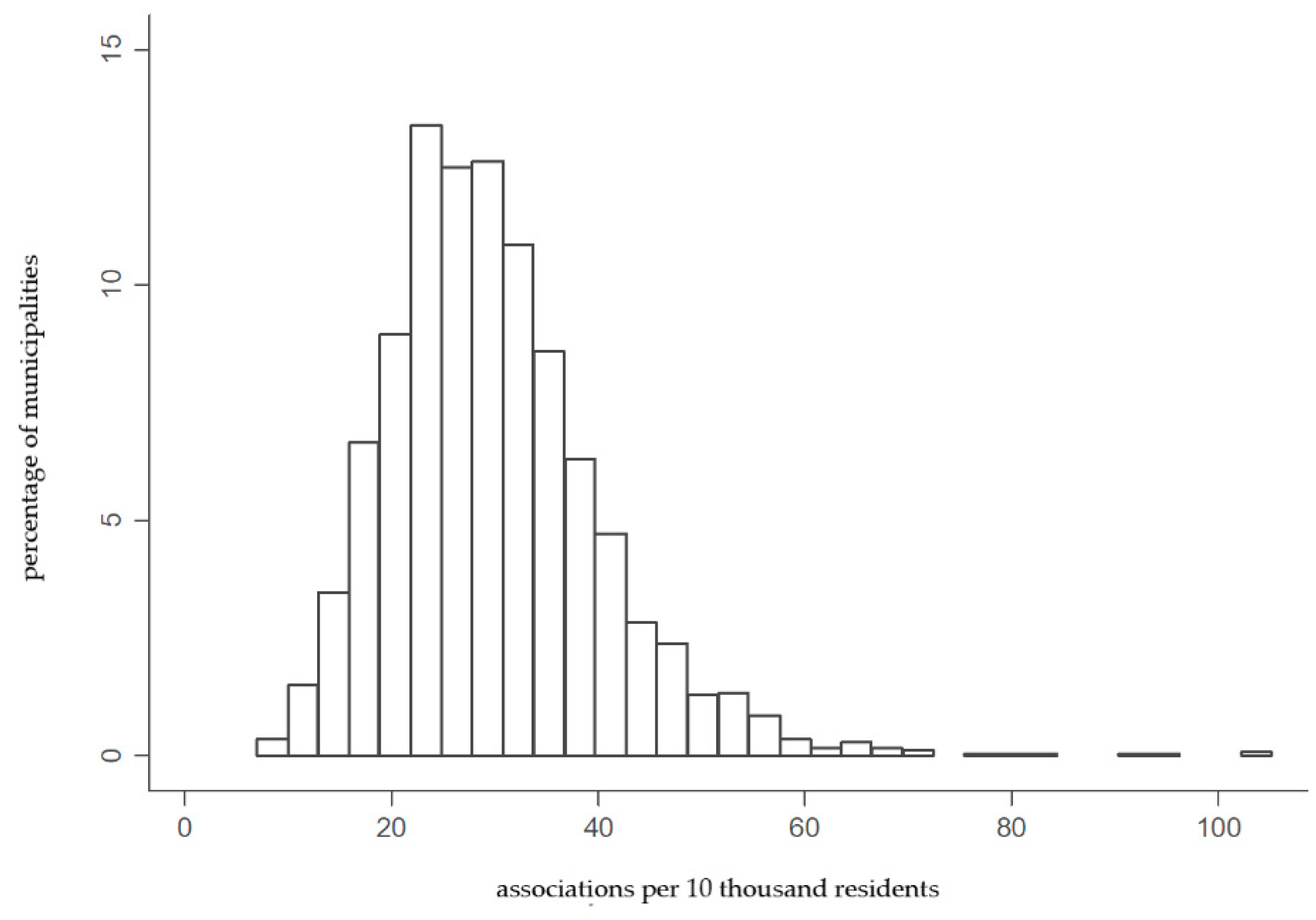

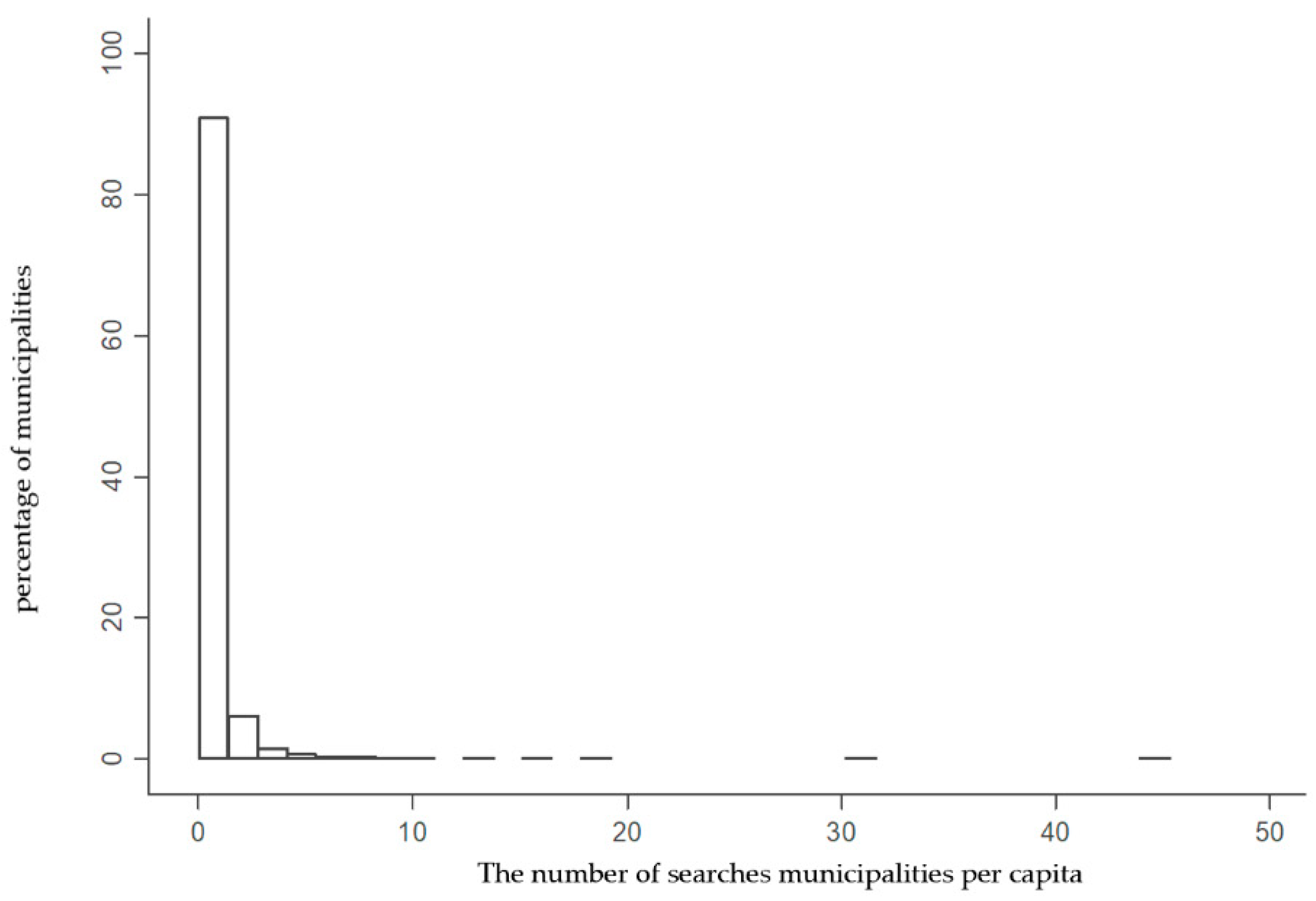

Below,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present distribution of three independent variables, i.e., human capital, social capital and tourism. In turn,

Table 3 shows the distribution parameters of the above variables.

As can be seen in the presented Figures (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), human capital, social capital and tourism have rightward skewed distributions—with an elongated right arm and most of the observations located near the minimum (and central) value of the distribution. This is also evidenced by the positive values of the skewness coefficient shown in

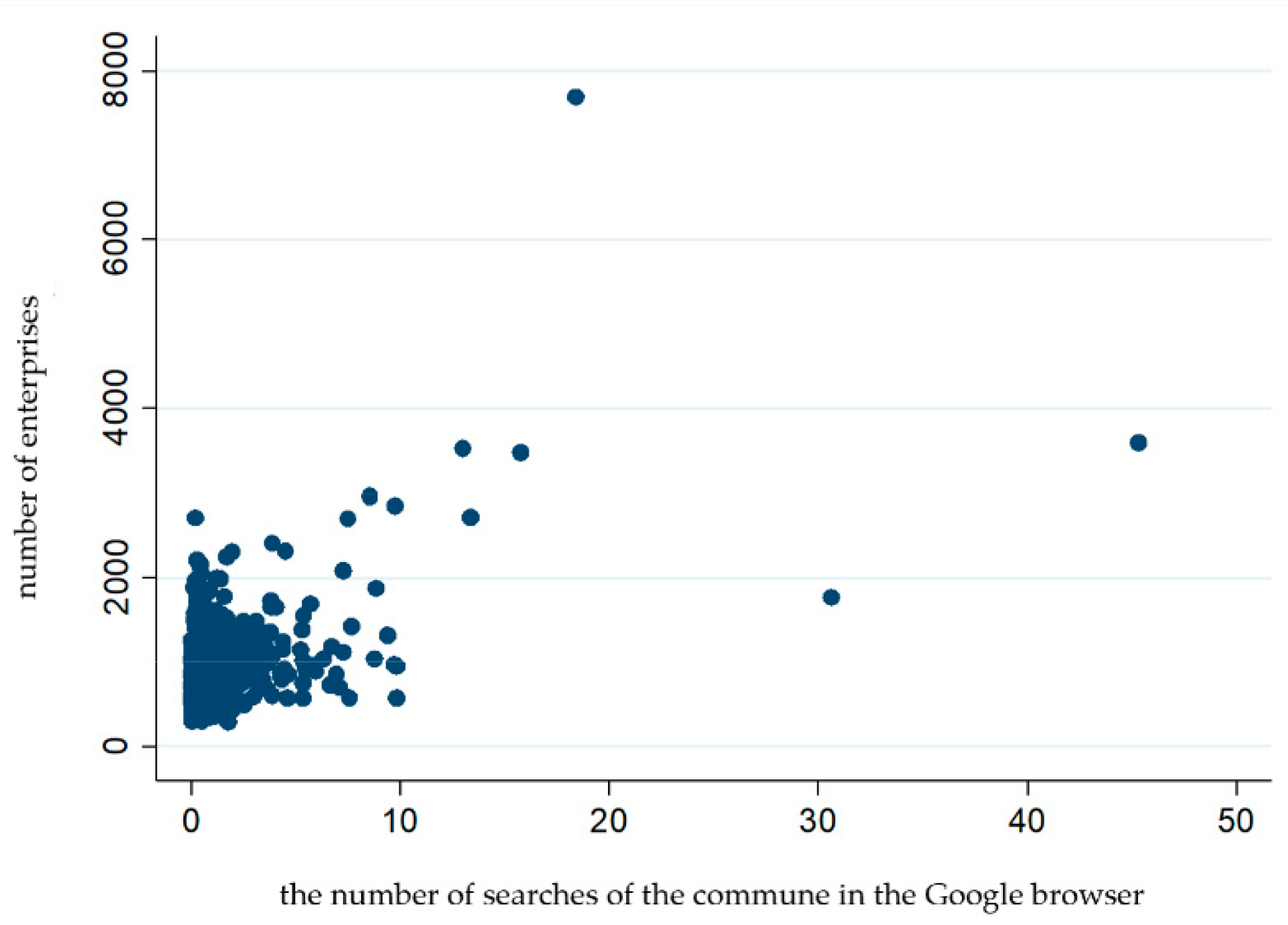

Table 3. The distribution of the tourism variable is characterised by the largest skewness, it is strongly rightward skewed—the skewness coefficient is 14.9 and the standard deviation exceeds the expected distribution value more than twice. The Figure of this variable shows many single observations, for which the values of this variable differ significantly from the mean value and the distribution median.

Table 4 presented below presents the 20 most atypical municipalities in terms of search frequency.

The number of queries in the Google browser per person represents the image of the municipality as a tourist destination. For businesspeople who rent rooms to tourists, the main source of customers are portals such as Booking.com, nocowanie.pl, etc. The highest score in terms of the number of searches in the Google browser per person has Krynica Morska, which is very much influenced by the relatively small number of inhabitants of this municipality. Karpacz is the only non-coastal municipality with more than 10 searches per inhabitant. At the same time, it is a less monthly differentiated search with much lower maximum values. While in coastal municipalities, the seasonality of Google queries is becoming apparent. Out of 20 observations with the highest number of queries per one inhabitant in Google, 8 are coastal municipalities, 5 municipalities are related to mountain tourism and the rest to specific local values or attractions (including health resorts). Municipalities on this list have very high values of entrepreneurship density. Two representatives of eastern Poland stand out with much lower results in comparison with the remaining eighteen: Solec-Zdrój has 579 enterprises per 10,000 inhabitants and Bałtów 580. Therefore, we can advance a thesis that, despite considerable recognition and numerous queries in Google, municipalities from the east of the country derive much lower benefits from their brand than others (especially those from Lower Silesia). The reasons for such results can be found in the generally lower affluence of this part of Poland, as well as in the poorer clearway with large urban centres. The statistical analysis points out, however, to the interaction between human capital and tourism (discussed below). Bałtów and Solec-Zdrój, despite their high recognition, do not show high entrepreneurship density results. Possible, this is caused by the very low percentage of people with higher education in both municipalities, which is only 3.6%. Therefore, a hypothesis can be put forward for further research that entrepreneurship in tourist municipalities can only develop after reaching a certain level of human capital. In order to achieve tourist success, human potential is necessary to see the opportunities and take risks associated with one’s own business. A key skill in tourist municipalities becomes managing one’s own brand on the Internet (both on the part of the municipality and the entrepreneurs themselves) and attracting customers there. Due to the new way of winning customers, such municipalities need educated people with marketing experience. The task of local self-governments focusing on tourism will thus be to skilfully support the villages in order to attract or retain people with high human capital. It also seems to be crucial from the point of view of the need to adjust the potential of municipalities to the requirements of Industry 4.0, the development of which, as previously indicated, will require the development of human capital.

To sum up, the variable “tourism” has a lot of atypical observations with very high values. In the case of two subsequent independent variables—human and social capital—their distributions can also be considered rightward, however, in this case the number of atypical observations lying at the right extreme of the distribution is much smaller than in the case of the tourism variable.

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the most atypical observations for human capital and social capital variables.

The municipalities with the highest percentage of people with higher education are cities such as Warsaw, Poznań, Wrocław, Gdynia, Kraków etc. Often these are academic cities and university graduates look for opportunities on the local labour market. A large group consists also of representatives of the Warsaw agglomeration (Michałowice, Piaseczno or Łomianki), and a smaller group of representatives of Poznań or Szczecin agglomeration (Dobra Szczecińska). In the comparison of twenty observations with the highest percentage of people with higher education, there is no municipality that would be located outside the agglomeration of the capital city of the voivodship.

Atypical observations of municipalities with a large number of associations in relation to the number of inhabitants are often tourist municipalities like Białowieża or Mielno. In these towns, the associations, apart from referring to the tradition of the “small homeland”, also perform duties commissioned by the municipality, especially the management of tourist traffic. Interestingly, this variable is dominated by municipalities associated with mountain tourism, not coastal tourism. The second visible group constitute municipalities with large human capital, such as Sopot or Warsaw.

Table 7, presented below, shows the conditional parameters of the distributions of the explained variable, depending on whether the municipality belongs to an agglomeration or not.

As indicated by the data included in

Table 7, municipalities belonging to an agglomeration are characterised by a much higher level of entrepreneurship than municipalities not being part of an agglomeration. In case of the first group of municipalities, the average number of enterprises registered in a municipality is 1051, while for the second group of municipalities, the average is 725.

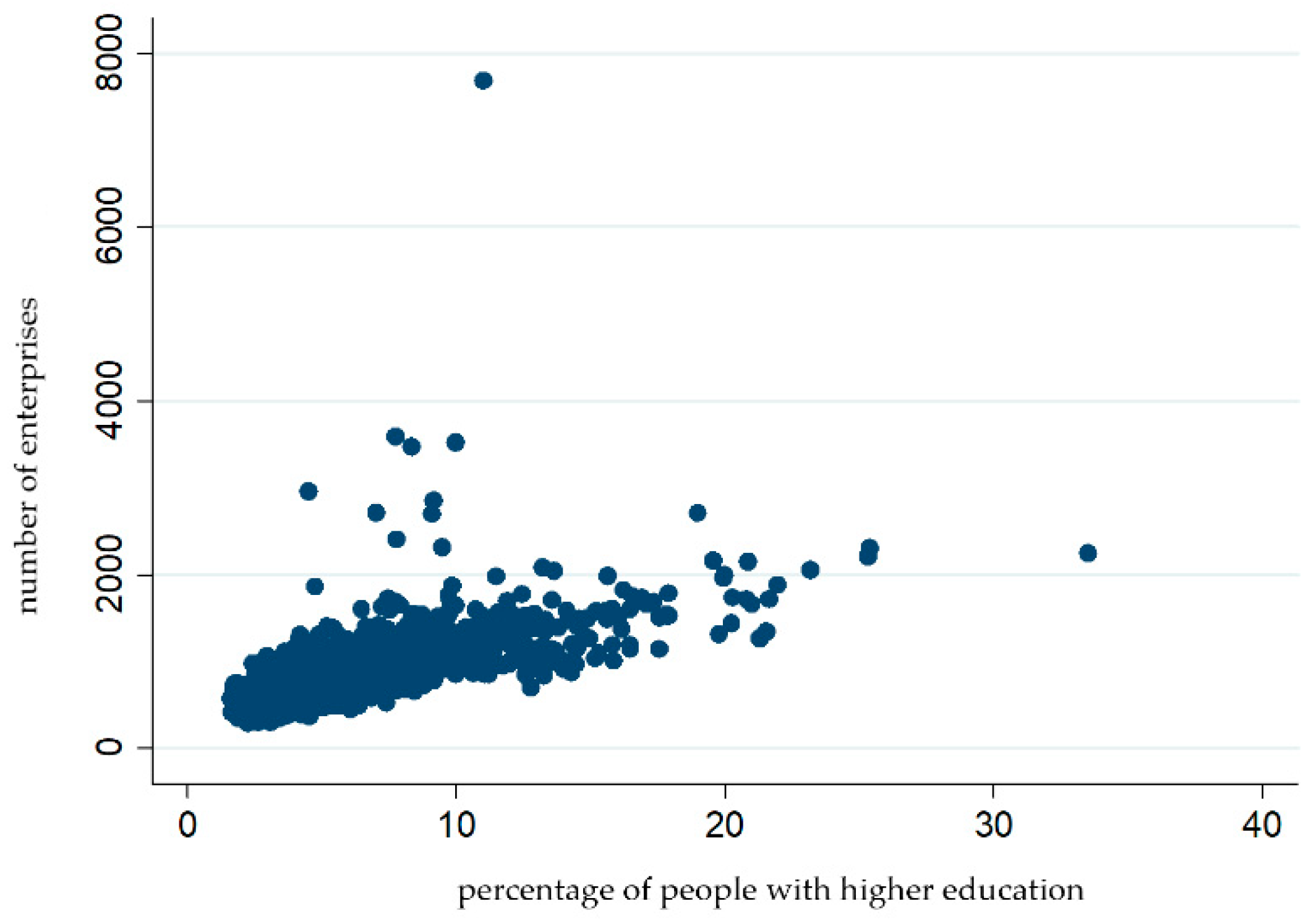

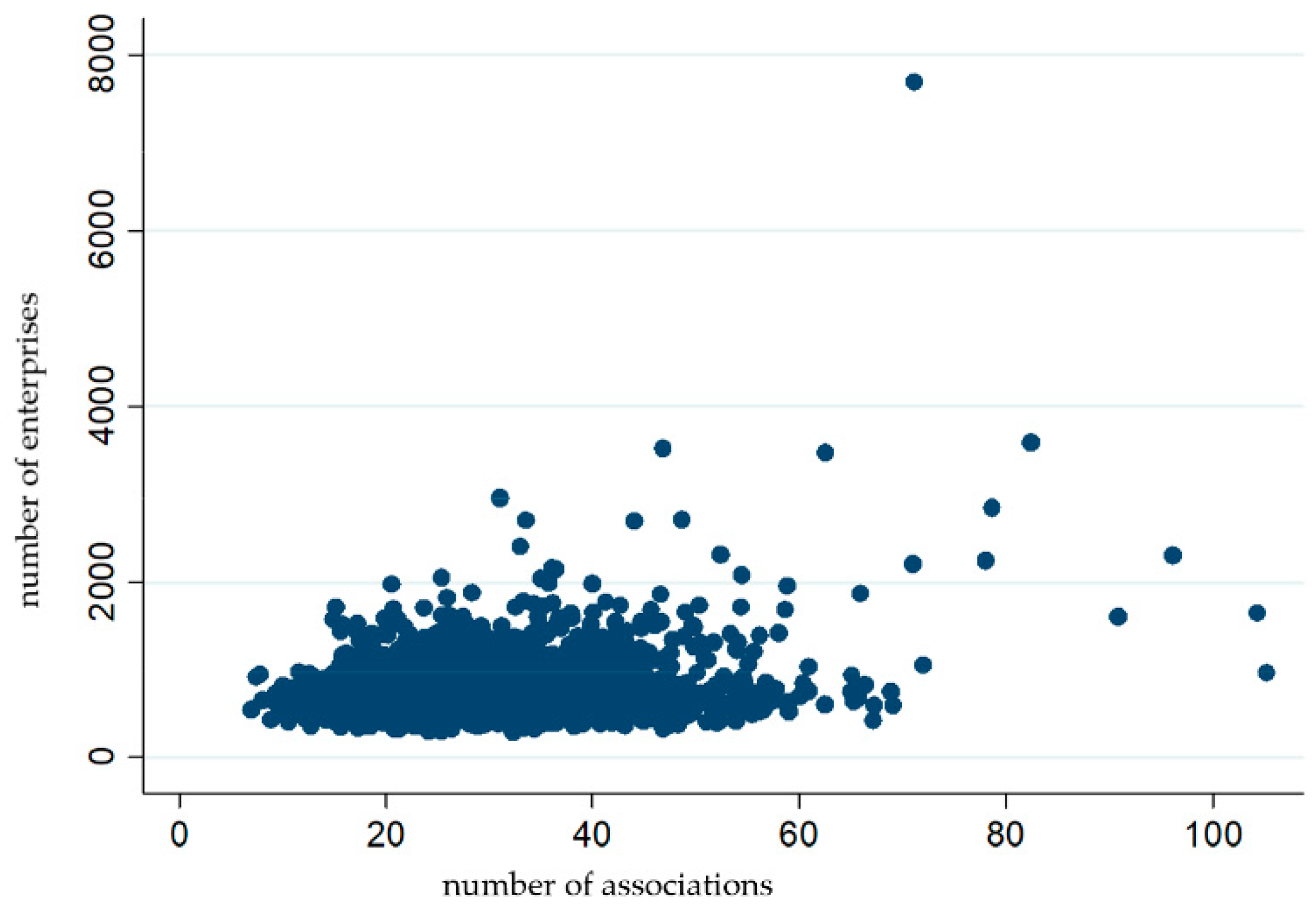

The relationship between the continuous independent variables and the dependent variable is illustrated in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 below.

From among the presented two-variable relationships, the linear relationship between human capital and entrepreneurship is clearly visible (

Figure 6). The relationships between the other variables—social capital and tourism and entrepreneurship—seem less clear (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). In case of all three Figures there are atypical observations—far from the other observation units.

The transformation of all continuous variables of the model into logarithms has made the dominant majority of relationships between the independent variables of the model and entrepreneurship statistically significant (except for the Hel observation, see

Table 8).

Referring to the main explained variables, an increase in the level of social capital in the municipality by 1% results in an increase in the number of enterprises registered in a municipality by 0.07% (seven hundredths of a percent). The estimate value for the agglomeration variable is 0.14. This means that if this variable changes from 0 to 1, the number of enterprises registered in a municipality will increase by 14%. In the variable voivodeship, the reference category against which comparisons are made is Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship characterised by the highest entrepreneurship coefficient. The level of entrepreneurship in the remaining voivodeships deviates from it in a negative direction, which is reflected in negative values of coefficient estimates for individual voivodeships. Lubelskie and Podkarpackie voivodeships are most deviated in a negative direction from the level observed in Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship—by 44%. On the other hand, the Dolnośląskie and Wielkopolskie voivodships are the least negatively deviated ones: by 5% and 7%, respectively. A very interesting result is the one for the Mazowieckie voivodeship, which is as much as minus 23% compared to the Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship. The Mazowieckie voivodeship can be treated as two different regions: the Warsaw agglomeration and the rest of the voivodeship, which is moderately developed compared to the rest of the country. If human capital—the percentage of people with higher education in the municipality—increases by 1% (relative to the initial value), the number of enterprises in the municipality will increase by 0.48% (i.e., half a percent). The estimated dependence is therefore very strong, as it means that human capital has a large impact on the number of enterprises registered in the municipality. The analogous effect on tourism is, however, much weaker: an increase in the value of this variable by 1% is associated with an increase in the number of enterprises by 0.02% (two hundredths of a percent).

The analyses carried out confirmed a positive and statistically significant correlation between the number of enterprises in a municipality per ten thousand inhabitants and human capital (H1), social capital (H2), tourist attractiveness (H3), agglomeration (H4). On the other hand, there are very few municipalities which reach the predicted value approximate to the observed value without using one of the main resources. A strong influence of resources on entrepreneurship enables the formulation of the fifth hypothesis (H5) that the creation of entrepreneurship by local authorities is a trace phenomenon and its level is mainly determined by the resources of a given municipality. On the basis of the model, it can be assumed that attempts to stimulate entrepreneurship without taking the characteristics of the municipality and its natural resources into account will have little effect. The success of the municipality will be determined primarily by the resource “pension” (the sum of accumulated resources over the years) and the ability to manage it. The optimal strategy for local authorities is to adapt tools stimulating entrepreneurship to their resources.

When analysing the influence of individual variables on entrepreneurship, a strong correlation between the dependent variable and higher education is visible. Human capital causes the highest growth in entrepreneurship in the model, per 1% of growth in entrepreneurship. There is concern that the impact of this variable on entrepreneurship may be partially apparent. The study sought to reduce the impact of this variable by including other independent variables potentially correlated with human capital and entrepreneurship. Further attempts to make sure that the impact of human capital on entrepreneurship is not apparent would require the inclusion of data from the individual level in the model and the transfer of analyses to the level of individual enterprises. This is the biggest challenge for this stage of analysis. On the other hand, the theory clearly indicates the positive impact of human capital on entrepreneurship in the conditions of the development of Industry 4.0 [

41,

42,

43,

44,

69]. The very high strength of this relationship remains the main doubt. The communist past of Poland and the strong link between higher education and agglomerations may constitute an explanation. In the Polish People’s Republic, there was no such a demand for white-collar workers as we have in the current economy, and the transformation and new production methods forced changes in the structure of education. New, better paid jobs have increased demand for education. Systemic changes released a huge amount of resources and caused their relocation, which affected Poland in the regional aspect and further strengthened the growth in agglomeration importance. The liquidation of old jobs, such as local industrial plants or State Agricultural Enterprises, resulted in the outflow of people from smaller towns to cities and their agglomerations. Taking into account both the enormous changes in the Polish economy and the development of Industry 4.0, one can formulate a thesis that the results related to human capital are so high as a result of mutual support of global and national trends. The intensification of the human-machine relation resulting from the development of Industry 4.0 [

70], puts greater demands on employees, which increases the importance of human capital. The need to develop human capital in companies introducing technologies 4.0 is also confirmed by other studies [

71]. This means that there is a need for appropriate changes in vocational training systems [

72] and this should be the task of regional authorities.

A large role of human capital is consistent with global research, however, currently the key role in spatial analyses of the economy is played by knowledge and agglomeration [

35,

64,

65].

Our research shows that a 1% increase in the value of the tourism variable is related to an increase in the number of enterprises by 0.02% (two hundredths of a percent). This is a much weaker dependence compared to human capital; however, it is also noticeable. This variable, however, enables a significant increase in the number of observations explained by the model because many atypical observations (the three most important ones include Karpacz, Krynica Morska and Hel) are related to tourism, and 11 of them are among the 20 municipalities with the largest number of enterprises per ten thousand inhabitants. Tourist municipalities have very strong brands being created over the years. Attempts to take over potential customers by other municipalities will be very difficult and require large financial outlays or the building of large tourist attractions. However, this is possible and seems to be an appropriate strategy in the context of opportunities and threats accompanying the development of Industry 4.0. Such opportunities are available, among others, to attractively located former industrial areas, where the currently liquidated industries used to dominate [

73]. It is also worth to take actions in order to restore the attractiveness of regions experiencing a tourism crisis, as the benefits of tourism are diverse and lasting [

74].

The activities of municipalities on the Internet and the development of digital products to influence consumer purchasing decisions are also important [

75]. According to the Pencarella study (2019), in the near future, tourism ecosystems and territories will not only be able to rely only on digital innovations, but will have to take intelligent tourism prospects into account, such as sustainability, closed economy, quality of life and social value; they should also strive to improve the quality of tourism and increase the competitive advantage of intelligent tourist destinations [

59].

The key prerequisite for the creation of the tourist profile of the region is having adequate resources—natural or created tourist attractions. This means that a local development strategy based on tourism is not possible for every municipality.

The problem of seasonality in regions with tourist specialisation should also be noted. Empty tourist facilities take up space and seem to be dead, which discourages tourists in the low season. It resembles the problem of empty “second homes” during the off-season in the Austrian Alps [

76]. Outside the summer season, most coastal towns are at most half-dwelt settlements. Seasonality of tourist traffic and decisions to invest in education of children lead to outflow of highly qualified people from tourist towns. At the same time, the interaction in the model shows that tourism entrepreneurship needs people with high human capital for the purposes of development. To sum up, it seems that in order to resolve the biggest problem of these municipalities it is necessary to maintain or acquire people with high human capital.

The agglomeration variable is theoretically very important. The model takes all municipalities located in voivodship agglomerations into account. The average number of enterprises registered in a municipality belonging to an agglomeration is by 14% higher than in a municipality not belonging to an agglomeration, with the values of the other variables remaining unchanged. This is a very good result. The municipalities which stand out against Poland are located in the Warsaw and Poznań agglomerations in particular (as atypical observations). In Poland, the differences between the Warsaw agglomeration and the rest of the voivodship are particularly worrying. This shows that the differences between the central and peripheral regions are broadening. The factors that hinder this process, such as the transfer of production from Warsaw, are conducted rather within the agglomeration. The development of Industry 4.0 is also likely to be beneficial for agglomerations or regions in close proximity to agglomerations. From the point of view of other regions, this would be an extremely unfavourable phenomenon due to the fact that an agglomeration is a completely independent resource, as opposed to tourist attractiveness. However, studies of the criteria for the selection of locations for Industry 4.0 show that companies will move from existing industrial centres, where access to labour or raw materials has been an asset, and choose environmentally friendly locations [

77]. It seems that investors are unlikely to abandon the agglomeration because of the still significant transport costs and the change in the structure of demand for workers—they will need fewer but more skilled workers. As previously demonstrated, a higher level of human capital is observed in metropolitan regions. Moreover, as the research of the North Jutland region shows, a considerable challenge for regions located far away from a metropolis may be the distance from important markets and industrial partners [

78]. Other authors claim that even though industry 4.0 was theoretically supposed to make it possible to produce everything in any place, the production places have remained unchanged for years [

79] and that the role of industrial clusters will not diminish [

80,

81,

82,

83]. This seems to be caused by the fact that the benefits of the agglomeration are still very important for many companies. Analysing the well-developed industrial region of Stuttgart, Hertwig et al. (2019) claim that with little effort, the local administration is able to support a symbiosis of sustainable development goals, Industry 4.0 and the goals of enterprises in the area [

83]. Given the opportunities that industrial development 4.0 opens up for agglomeration areas, it is also necessary to take the emerging requirements for these areas into account—the need for adequate infrastructure and basic resources, such as water and energy and warning systems [

84]. A very interesting observation also refers to the possibility of switching entire clusters (Marshall’s industrial districts) to 4.0 solutions [

85]. Institutional isomorphism, conditioned by adequate social capital, can play a key role here [

85].

For social capital, an increase in the value of this variable by 1% is associated with an increase in the number of enterprises by 0.07% (seven hundredths of a percent). This is more than three times higher than for the tourism variable. In some municipalities, the associations are used by the authorities to carry out tasks related to tourism and promotion. In other localities organisations connected with cultivating local traditions, implementing participatory budget or developing relations with municipalities from other countries are set up. Referring to the theory of social capital, higher trust between the inhabitants should be observed in municipalities with a large number of associations, and thus lower transaction costs [

86,

87,

88,

89]. There is also another factor related to entrepreneurship, i.e., high proactivity and flexibility of citizens [

90], their ability and willingness to organise and implement their own projects and ideas. There is a kind of project experience that can be used for the development of one’s own company, which is particularly important in the context of the likely need to change profession at least several times during one’s career. A lower level of social capital, expressed, e.g., by communication problems, may have a significant impact on the adaptation to the requirements of Industry 4.0. These phenomena were noticed by Brixner et al. [

91]. The studies referred to the scale of countries, but similar phenomena can be observed on a local scale.