1. Introduction

The welfare state ideology is gradually changing in the developed countries’ political agenda. Under these conditions, it is becoming increasingly difficult for government services to fully meet the needs of all citizens in need of state assistance, due to the increase in the number of migrants, unemployment, and population aging [

1]. Certain changes in the relationship between the state and the population are also taking place in the post-Soviet countries. The socialist regime systematically fostered paternalistic relations in society, and public services were accustomed to centrally solve most social problems for a long time [

2] (pp. 213–226). After the fall of the communist regimes, not only ideology and public policy changed, but also public service underwent substantial reforms. Significant changes needed to be carried out in redefining the relations between the state and nonprofit sectors, between civil servants and citizens in the post-Soviet countries [

3] (pp. 101–119), at the same time as the developed countries felt the need to encourage more civil society involvement in the public affairs.

These processes force the public sector to reform, since the state responsibility for solving social problems is redistributed, public administration approaches are changing. First, because of the social, economic, and political instability of recent years, the state policy of many countries is increasingly aimed at sustainable development. It is not by chance that the United Nations, in its document “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” listed, among the 17 goals, one concerning the “promotion of peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” (SDG 16) that create room for the “free, active and meaningful engagement of civil society”. Another significant sustainability development goal in the list fosters “effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships” (SDG 17) [

4]. However, practically all 17 goals can be interwoven in the public administration, planning processes, measures, and strategies, as targets for steering the development in a sustainable manner. Second, the identity of the citizens themselves is being reevaluated. They become increasingly involved in management practices and in solving various social problems. Volunteering plays a significant role in all these processes around the world. Volunteers properly help during both manmade and natural disasters, they help solve environmental challenges, and fight poverty. It is volunteers who work in social strain areas in local communities. They assist professionals’ work with the aged, the disabled, and the orphans, with increasingly more complex issues, while the government funding to address these challenges is diminishing. As the international organization United Nations Volunteers (UNV) so adequately states, “The most comprehensive estimate of global volunteering today puts the global informal and formal volunteer workforce at 109 million full-time equivalent workers” [

5] (p. 11).

According to the world community, the integration of volunteering into different countries’ politics, lawmaking, and social planning should be implemented gradually. The UNV states that such a universally accepted way of national policy actualization helps achieving the sustainable development goals agreed and accepted by the entire world community [

6].

In the 21

st century, changes occur in all countries, both in the popularity of volunteering, and in the management of volunteering. In countries with different political backgrounds, with different cultures of volunteering, of state-third sector interaction, where volunteers are a driving force, these changes happen in different ways. It is not surprising that the benefits of volunteering for society are perceived unevenly and the maturity of civil society differs from one country to another. Government intervention in the volunteer sector carries risks for civil society, nonprofit organizations, and public activism. Postcommunist countries bear the memory of the mock voluntary labor, publicly presented as springing from community initiatives, but later turned into mandatory tasks, especially towards the end of the 20th century. The nonprofit sector was formally established by the state and had nothing to do with civil initiatives. In postcommunism, the nonprofit sector in such countries emerged as an underdeveloped segment, fragmented and dependent on governments or international donor funds [

7]. For example, Bulgaria ranks 144th out of 145 countries in terms of formal volunteer population, Romania 139th, Hungary 115th, Poland 99th [

8]. Thirdly, the population is distrustful of many public initiatives of the government, and officials themselves are not always correct in relation to volunteers and nonprofit organizations.

Despite all the differences identified between the situations in postcommunist countries by comparison to the developed countries, the interaction between the state and civil society is actively reforming public policy. The ideological basis of “coproduction” is seen as a valuable path to reforming public service, planning, and delivering effective public services, responding to a democratic deficit and a path to an active civic position and active communities, and as a means of attracting additional resources to deliver public services [

9]. This is an important way to work with public servants, nonprofit professionals, and volunteers to jointly produce public goods, as well as a government policy to promote such interaction.

The official position of the Russian Federation is to completely endorse the position of the United Nations Volunteers and make room for the civic initiative in partnering with public administration, for producing public goods. In accordance with this position, starting with 2017, the state administration started implementing innovative solutions that determine not only the national policy, but also the activities of government services, federal civil servants, and civil servants in each Russian region. Although innovation in Russian regions has different outcomes, depending on the traditions, economic development, and social factors, efforts have been made to implement federation-wide norms, encouraging volunteering [

10]. The Agency for Strategic Initiatives (ASI) has developed the national Volunteer Support Standard, which is universally implemented in the country and determines the creation of a supportive environment for Russian volunteers by federal and municipal civil servants [

11]. The educational value of this document was stated by the head of ASI, Svetlana Chupsheva, who pointed out that the standard allows for “metrics for assessing volunteer activity, so that each region that implements the Standard sees the economic and social impact of those projects supported by non-profit organizations and volunteers” [

12], thus understanding the value of volunteering and the progress towards a sustainable action in managing public affairs.

The present article presents the results of the analysis of the current situation of governmental support for volunteering in Russia as a separate case of creating conditions for the state to encourage the engagement of people in volunteering. Even though the Russian government’s initiative in this area was recognized by the world community as the best practice of public administration [

5] (pp. 78–79), there are still gaps to be filled in the knowledge of the process. The study was carried out with the aim to reveal the perception of the stakeholders concerning the interaction between public administration and volunteer organization and to evaluate possible consequences and risks to civil society in the state-led initiatives, which may foster or hinder the coproduction of public goods, services, and policies.

2. Theoretical Approaches to Governmental Support for Volunteering

The literature on volunteer work shows that there is considerable evidence to connect volunteerism and the social well-being of people, even though the number of people engaged in volunteering in different countries is different [

13] (pp. 29–51); [

14] (pp. 37–150). Researchers note that, at the macro level, the developed democracy has a positive effect on volunteering [

15,

16,

17,

18], as well as on the increased government spending on social protection per capita [

19,

20], higher level of education and religiosity [

21,

22,

23,

24], and higher per capita GDP [

17,

25]. All the above factors belong to the criteria that define volunteering development, institutional context of volunteering initiatives actualization, which include the relationship between the state and nonprofit organizations.

Currently, researchers are focusing more and more on the “growing intervention of governments in volunteering” [

26] (p. 73S). In the literature, experiences of actualizing stipended national service volunteering (SNSV) are analyzed within relations between the state and nonprofit organizations and volunteers. Researchers note their professional organization, as well as positive effects on both volunteers and beneficiaries, and the local community [

27]. Public services act as intermediaries. They implement government programs, in which volunteers solve their problems and solve the problems of society at the same time.

Infrastructure and professional staff development for the actualization of such programs in different countries, which affects the quality of volunteering and the number of volunteers, show that in the future they will gain more and more popularity. However, from the researchers’ point of view, to fully take advantage of SNSV requires a clear strategy, measurable outcomes, and sustainable partnerships across community-based organizations [

28].

Civil servants’ increased interest in volunteers as an additional galvanizing resource for providing citizens with various services in social institutions and public services leads to a change of volunteer motivation [

29]. Such processes blur the lines of volunteering, however, advantageous effect of this activity both on the volunteers themselves and on the society allows volunteer involvement to change [

30]. The inclusion of volunteerism as a social movement in the development of civil society, local communities and third sector in different countries continues [

31].

The nonprofit sector is traditionally seen as a buffer between the state and the society and one of its functions is to reduce social tension. Nonprofit organizations (NPOs), in which volunteers are one of the main resources, take on the functions that the state does not actualize for various reasons [

32] (pp. 7–20). Researchers note that the healthy third sector is characteristic of democracies. Sustained voluntary sector and systemic cooperation between the state and NPOs are important. In recent years, NPOs have been limited in their ability to generate sufficient resources, even in democratic countries; they are vulnerable to particularism and the favoritism of the wealthy, prone to self-defeating paternalism, and have at times been associated with amateur, as opposed to professional forms of care. These problems are “voluntary failures”, the existence of which justifies the need for governmental support and assistance to the voluntary sector, and emphasizes the special importance of collaboration between the government and the nonprofit sector [

33] (p. 42). This is especially important for post-Soviet countries. These countries, including Russia, typically have a weak third sector [

34]. In NPOs, there are not enough skilled specialists and volunteer management is not developed as well. Volunteering is not very popular with the citizens of these countries, and the motivation of volunteers is also different [

35,

36,

37]. For instance, in 2000 in Russia, very few people understood the concept of volunteering. This term was literally absent from the information agenda even in 2013. According to the results of a survey by the Public Opinion Foundation, only half of the people knew something about the activities of volunteers in their city (village) [

38]. The volunteers themselves analyzed the attitude towards volunteers and their activities and noted that the volunteers’ activities are taken by other people with a “certain misunderstanding” [

39] (p. 192). Moreover, Russians do not seem to trust nonprofit organizations in general [

40]. There was practically no volunteering infrastructure development before Kazan Universiade, and resource centers and vocational training for Games Makers only started due to the Olympic Games in Sochi in 2014 [

41].

Back in 2013, Koen P. R. Bartels, Guido Cozzi, and Noemi Mantovan suggested a recommendation aimed at encouraging volunteer activities, “for public spending to increase volunteering, governments and voluntary organizations should cultivate local abilities and volunteering infrastructure based on collaborative relationships” [

42]. There is a need of governmental resources, the efforts of civil servants, the planned consistent policy aimed at volunteering promotion, the infrastructure development, and the systematic support for the third sector to create an ecosystem for sustainable volunteering in the countries with the weak third sector [

5]. While professional public service workforce is confident in carrying out its tasks, the complexity of governance and the sustainability development goals require that civil servants make room for collaboration with all forces in society, through multistakeholder forums, participatory budgeting, and community-driven development [

43]. In the Russian Federation, the lesson is learned, though at a pace measured in the present study.

Nonprofit organizations and volunteers are treated as coproducers of public services, which are included in the coproduction concept, as defined in the literature on public administration by Elinor Ostrom [

44,

45]. Volunteering is a key component of coproduction, since volunteer coworkers actively provide community services to their communities at no cost. In the conditions of socio-economic instability, the participation of coproducers in the sale of public services becomes the most relevant—“the COVID-19 pandemic created a critical need for citizen volunteers working with government to protect public health and to augment overwhelmed public services” [

46].

To achieve coproduction, the state needs to seek ways of facilitating the work of coproducers, both with regard to the task itself and with regard to the provided information [

47]. In order for coproduction to develop and be maintained from below, certain conditions must be met: a sense of community is required, strong enough for people to work together towards achieving a common goal; institutions that allow people to play a meaningful role in the sharing of public goods and services are needed. If these conditions are not met, it cannot be assumed that coproduction will be successful [

48]. The leading role of the state in creating these conditions and developing volunteering from above is an example of top-down and state-driven coproduction that differs from the bottom-up coproduction [

46].

China’s experience shows that the state can be the initiator of coproduction, the driver of its formation in societies with undeveloped democracy and a weak third sector. This raises the research question: can the leading role of the state in the development of volunteering and NPOs in Russia lead to the democratization of society and to the implementation of coproduction of public services?

Coproduction as an interaction requires awareness and trust among those involved in the development process. In our case, they are officials who create conditions and encourage the population to become volunteers, to implement their volunteer activities for the reproduction of the public good; the very population, which already has experience of volunteering and is determined to interact to promote public services through participation in various volunteer projects; NPO specialists as intermediaries between the state and the population, initiators of projects that lead to the in-productivity of volunteers and employees of volunteer centers.

The research hypotheses of the study are the following:

The experience of volunteering determines the high appreciation of the state’s contribution to the development of conditions for the implementation of coproductivity.

Previous experience of lack of systemic interaction between NPO leaders and local officials does not build confidence in the state’s intentions to support volunteer projects and develop them in the context of coproductivity.

Officials underestimate the potential of the population as volunteers, able to productively produce public goods and themselves are limited in intentions of volunteering and interaction with NPOs.

3. Materials and Methods

The analysis is based on a set of methods: the analysis of documents, the questionnaire survey of people of Russia, the expert poll of public servants and volunteer resource centers’ leaders, large NPOs, and secondary data analysis. Moreover, the analysis of the state policy of support for volunteering is carried out with respect to the following parameters: the awareness and evaluation of the national measures of the governmental support for volunteering. To substantiate our findings we used examples drawn from the Year of Volunteering events, the Association of Volunteer Centers activities, the creation of the state information portal for volunteers and NPOs, the implementation of the governmental support for volunteering standard in the activities of government civil servants in the regions, as well as the evaluation of informational, financial, consulting, organizational measures to support volunteer organizations by regional and municipal civil servants.

The article analyzes the total set of political decisions and statutory instruments that protect volunteers and stimulate their activities. The authors analyze the structures that help steer volunteers, maintain, and support them in both public and nonprofit sectors. All the elements that are analyzed in the case determine the management strategy, which, in accordance with the national Standard of Volunteer Support, should be implemented in each region and municipality of Russia. The innovative approaches are evaluated in the public administration in this area at the federal level, at the level of individual Russian regions, and in the management of individual municipalities.

The authors analyze documents, informational resources data provided by public authorities and volunteering empirical studies. The study presents innovations social expertise in the public area in the assessments of people involved in organizing volunteer movements in different parts of Russia (civil servants responsible for this movement, infrastructural NPOs’ heads, and the citizens experienced in volunteering). Their considerations on the effectiveness of the government programs, activities, and managerial decisions of civil servants responsible for supporting volunteers in the whole country and in certain regions are also presented in this study. The focus is on how public employees cooperate directly with volunteer organizations and associations in their cities, how they see the prospects and problems of actualizing for volunteers in the activities of local governments.

The data from the document analysis are supported by the results of three sociological studies that were carried out from September through December 2018.

The first study is a questionnaire-based survey of Russians having some experience in volunteering, carried out in December 2018. According to official statistics, the level of participation of the Russian population aged 15–72 years in volunteer work is 1.3% (approx. 1.5 million people). The sample for the survey included 14 to 60 years old Russian citizens having experience in volunteering organized by nonprofit organizations involved in projects of regional universities and colleges, centers, and institutions operating under the local administrations, leisure and social institutions of all regions and republics of the Russian Federation (N = 830, sample type—quota). The sample was formed according to three characteristics: by gender and age, by the volunteer percentage in the population structure of each federal unit [

49] (p. 186). The respondents in the sample were 44% men and 56% women. The sample included 14% respondents with general secondary education, 23% respondents with vocational education diploma, 22% respondents with incomplete higher education, 41% respondents with higher education. According to the residence criterion, 16% respondents live in cities with the population of more than 1 million people, 57% in the cities with a population of 250,000 to 1 million people, 16% respondents are from medium-sized Russian cities with the population of 250,000 to 50,000 people, and 11% respondents from settlements with less than 50,000 people. The questionnaire was distributed on social networks of thematic communities, through the organizations of the Association of Volunteer Centers, as well as through the heads of regional resource centers of volunteering in the subjects of the Russian Federation.

The second study is a semiformalized survey of experts organizing volunteer projects in different parts of Russia, as well as the survey of regional volunteer resource centers heads (N = 121, type of sample—target). The study made it possible to analyze the specialists’ considerations on the effectiveness of measures to support volunteer initiatives at the federal level; it helped identify the volunteering professional organizers assessments in relation to the support of volunteer initiatives by regional civil servants in different parts of Russia. It analyzed the development of resource regional volunteer centers. Seventy-two percent of the respondents in this sample are women, and 28% are men. By education, 82% of respondents have a higher education degree, 12% have an incomplete higher education, 3% have a vocational school diploma, and 3% have a general secondary education. Eleven percent of experts have a work experience for organizations of over 15 years, 8% have a work experience between 10 and 15 years, 15% have a work experience of 5 up to 10 years, 66% have a work experience of less than 5 years. In the sample, 48% of all experts hold posts in various institutions with the organization of volunteering activities is included in the duties, 33% work in educational institutions as teachers, 14% work in other institutions, and 5% experts hold other positions. Forty-one experts are heads of regional volunteer resource centers.

The third study is an expert poll of the Sverdlovsk region municipal servants responsible for creating conditions for volunteer activities and interaction with nonprofit organizations in the municipal districts of the Sverdlovsk region (N = 94, the sample is continuous). According to the survey, innovative solutions to promote volunteering in local governments are analyzed. The choice of Sverdlovsk region municipal servants for analyzing their opinions on the case was due to the fact that this large Russian region was included in the lot of five pilot territories (there are 85 regions in Russia in total), where the national standard for governmental support for volunteering began to be implemented in 2017. The survey included 94 public employees. Nineteen percent—experts under the age of 29, 22%—30–39 years old experts, 37%—40–49 years old experts, 17%—50–59 years old experts, 5%—who reached the age of 60 years and older. The average age of public employees who participated in the survey is 41. The average length of the public employee service is 9.8 years. Fifty-one percent of experts hold positions in the “specialists” category, 49% belong to the “managers” category.

The set of research methods, covering all stakeholders as coproducers of public services, provides an understanding of the complex structure of relationships of all subjects, allows to characterize and evaluate the sense of community/solidarity of the producers and the effectiveness of institutions allowing people to play a significant role in the joint production of public goods and services [

9,

50].

4. Results of the Study and Discussion

4.1. National Strategy and Standard of Volunteer Support in Russia

Thanks to UN, the public recognition of volunteering as a general welfare is constantly growing. The United Nations Volunteers program made it possible for international community recommendations regarding the governmental support for volunteers and their organizations in different countries to be developed. The strategy has been developed (2016–2030), which suggests that volunteering should be integrated into their politics, lawmaking, and planning [

6].

In Russia, the volunteer movement has been rapidly developing over the past 10 years. Citizens’ volunteer initiatives are becoming the subject of public attention more often. The president of Russia declared 2018 to be the Year of Volunteering. A national action plan for the development of the volunteer movement was developed [

51]. The beginning of its implementation was visible during two major events: the presidential elections of 2018 and the organization of the Football World Cup in Russia. The change in the socio-political situation in Russia and in other countries has contributed to the fact that in recent years, it is the government and public servants who spare more effort to support volunteering at different levels: normative; organizational; methodical; informational.

Due to the existing restrictions on the interaction between Russian NPOs with international funds and grantors, in the conditions of economic instability and poorly developed charity culture in Russia, volunteer activities in most of their directions, as a rule, develop with direct governmental support. During the recent years, there has been a sharp increase in volunteering management institutionalization in Russia. Volunteer Centers Association includes more than 100 organizations across the country and provides expertise, methodological support on the volunteering development issues in Russian regions. There is a noncommercial network organization succeeding Sochi-2014 volunteer project, which has received massive governmental support.

The Federal Expert Council on Volunteering Development appeared in 2016 [

52]. Such councils should be created by regional civil servants in all 85 Russian regions and republics. Over the past two years, a series of national events where the topic of volunteering was one of the priorities has been held. A lot of volunteers from all over the country worked at the XIX World Festival of Youth and Students, which took place in Sochi, and charity and volunteering were included in the list of key themes of the festival. Russian National Volunteering Forums took place in December 2017 and December 2018. In 2018, 91 thematic days were organized, including country-wide and regional events for volunteers. In 2018, 14 international sporting events were held where volunteer support was organized [

53]. The federal information portal “Volunteers of Russia” [

54] was launched, where volunteers and volunteer organizations of all Russian regions can register, according to 73% out of 100% respondents (620 out of 830). This portal contains informational, methodological materials for volunteers and NPOs, as well as online educational courses on volunteering in different fields.

The Agency for Strategic Initiatives (ASI) developed the national strategic initiative called “Regional Volunteering Development”, which resulted in the development of governmental support for volunteering standard in the regions and republics of Russia. This standard was implemented in more than 50 Russian regions in 2019. This introduction in the activities of state and public servants should ensure equal volunteering access for citizens of all ages to opportunities that will take into account their motivation; combine the resources of business, nonprofit, and educational organizations in the actualization of joint volunteer programs on the basis of state and public institutions and volunteer centers. It should strengthen citizens’ trust in the nonprofit sector, as well as provide NPOs with a human resource for their development; it should increase the effectiveness of volunteering; and help raise additional money for the social sphere. The standard includes nine steps that must be implemented in public administration at the regional level and in the management of municipalities. Each region must issue regulations for the interaction between public authorities’ regional offices, and NPOs and voluntary organizations. A civil servant no lower than the Russian region deputy head has been appointed responsible for volunteerism development in the region. The volunteer council has been created. The resource volunteer centers should open in each region of Russia. Civil servants must sustain volunteer organizations financially; provide them with subsidies and grants. Civil servants should provide information support and popularize volunteerism, organize volunteers and civil servants’ training, and encourage volunteers. The standard assessment should be actualized in each region. The main emphasis is on organized volunteering, for which the state is rapidly creating and developing infrastructure, civil servants provide informational, consulting, financial, and material assistance to volunteer organizations in each region of Russia.

There were changes to federal law No. 135-F3 “On charitable activities and charitable organizations”, which determined the status of volunteer organizations, organizers of volunteer activities and volunteers, fixed the requirements that such organizations and individuals should meet beginning in November of 2018. Methodological recommendations on the organization of sports, social, cultural, and other types of volunteering began to be developed rapidly. The Presidential Grants Fund has begun actively financing projects of socially oriented nonprofit organizations on volunteer topics in the direction of “Civil Society Institutions Development”. In 2017 only, 216 projects were supported in this area allocating 658.99 million rubles [

55].

While the first version of the 2013 law draft excluded volunteering from the political sphere, in 2018 it can be stated that it was actively included in the context of the presidential election campaign and in the election campaigns of individual heads of regions and republics of Russia. The state budget supports pro-government NPOs—Russia-wide public movements. Victory Volunteers public movement (aiming to celebrate the victory in the second World War) has received governmental support and has been actively developing since 2015. In 2017 only, this movement organized and conducted 34 Russian-wide mass patriotic events and 8000 local events. Medical Volunteers movement has been developing since 2013. These days it includes 67 regional departments, 12,500 volunteers, more than 220 medical organizations and more than 110 medical universities and secondary specialized colleges. The patriotic NPO called the Search Movement of Russia is actively supported and developed. It includes 1428 search parties from 82 regions and republics of the Russian Federation. To support and develop volunteering for the Social Activity federal project, 7.4 billion rubles were allocated until 2014 [

56]. At the federal level, measures of governmental support for volunteering are included in three national projects, Education, Culture, and Urban Development. The norms for volunteer access to social institutions are developed, the standard for the interaction between municipal officials and volunteers was prepared and implemented.

The government plays an active role in initiating, financing, and promoting joint production at the community level, in which residents, NPOs, and private businesses become providers of social services and infrastructure. All the outlined measures show that in Russia (as in China) state-led coproduction takes place in the conditions of a weak nonprofit sector and civil society, as well as low income levels, and lead to strengthening the authority of the government and increasing the level of trust and loyalty of the population towards the state.

4.2. Governmental Support for Volunteering in Russian Volunteer Community Assessments

Hereunder, we analyze the level of volunteer awareness regarding the government support measures to promote volunteerism at the federal and regional levels. The Year of the Volunteer awareness proved to be high in the volunteer community: 71% of the respondents knew that 2018 was the year of volunteering in Russia and took active part in the organized events. Twenty-two percent of the respondents heard about this initiative, but did not participate in the events, and 7% did not know anything about it. The respondents from all regions of the Russian Federation were equally aware of the Year of the Volunteer in 2018. There are no differences across the country in the volunteer awareness level regarding the federal initiative. The awareness of the respondents, as well as their active participation in events, depend on how often they engage in volunteer work: the more respondents are involved in it on a regular basis, the better they are aware of the Year of the Volunteer events, and also take part in them. The results of the survey showed that 84% Russians volunteered about once a week, 71% respondents volunteer twice a month, 72% of respondents whose experience in volunteering is once every two to three months, and 41% of respondents took part in volunteer projects once or twice a year actively participated in the Year of Volunteer events (Gamma—0.373; p-value = 0.00). The respondents working in nonprofit organizations (84% of the surveyed people), state and municipal organizations (78% of surveyed people), public and religious organizations (69% of the surveyed people) attended the Year of the Volunteer events more often. Only 36% of the volunteers connected with for-profit organizations, as well as people with the experience in informal volunteer communities were aware of the Year of the Volunteer events.

Respondents evaluated the effectiveness of the events that were held as part of the Year of Volunteering in Russia, on a five-point scale (where 1—the events are not effective, and 5—the events are most effective). The average score is between 3 and 4. According to respondents, the least effective measures are those aimed at improving the legal protection of volunteers (3.5 points), supporting volunteer activity by civil servants (3.6 points), and strengthening ties between volunteers and volunteer organizations from different countries (3.6 points). The highest score was given to major forums and competitions (4.23 points) and the popularization of volunteerism in the media (4.13 points).

Eighty-nine percent of the surveyed volunteers are acquainted with Volunteers of Russia’s website, while 11% of surveyed volunteers declare that they do not know nothing about it. Fifty-eight percent of respondents were registered on the website, 15% visited it, but did not register on it, and 16% heard about it, but did not visit it. There is no proven connection between the location of a volunteer and their awareness of the website. There are two factors influencing Volunteers of Russia’s website familiarity. The first factor is the involvement in volunteer activities. The more often volunteers perform unpaid volunteer work, the more likely they will register on the website (Gamma—0.357; p-value = 0.00). The second factor is the level of respondents’ education. Sixteen percent of respondents with higher education do not know about the Volunteers of Russia website, while overall this figure does not exceed 10%. The percent of volunteers having higher education registered on the website is 52%, while overall it is 58%.

Respondents who visited the Volunteers of Russia website and registered on it highly appreciate its quality: 49% gave it 5 points out of 5, 39%—4 points out of 5. The average score given by the volunteers is 4.3 points. Among those who are registered on the website Volunteers of Russia or visited it, 17% took an online course on the basics of volunteering, and 47% plan to take it. Thirty-six percent of respondents are not yet interested in completing training on the portal. The more actively respondents engage in volunteer activities, the more likely they have been trained on the website or plan it: among respondents who have performed volunteer work several times a month or more, 20% have been trained on the website, 48–49% plan to do it. Seventy percent of the surveyed volunteers who are involved in volunteering several times a year (and less often) do not plan to study on the portal (Gamma—0.187; p-value = 0.01).

The “Volunteer of Russia” contest is well-known among most of the volunteers—86% of respondents heard something about it, among them 52% were aware of it, and 15% took part in it. Only 9% of respondents having volunteer experience in state and municipal institutions, 10% of those who participated in NPOs’ volunteer projects, 25% of respondents from self-help groups and informal associations, and 15% of those who acquired volunteer experience in a profit company as part of corporate social responsibility (CSR) or corporate volunteering programs know nothing about the contest.

The research team also examined what governmental support measures for volunteering in Russian regions were familiar to volunteers, whether they knew about the existence of resource volunteer centers, and if so, how did they evaluate the effectiveness of their work. It should be noted that most of the respondents (81%) knew or heard something about the best volunteer practices contests, awards, diplomas, letters of thanks; 75% of respondents knew about activities to popularize volunteering, about presentations, lectures, and festivals. Seventy-nine percent of respondents were aware of the rules for interaction between civil servants and volunteer organizations, 76% of respondents knew about resource volunteer centers in the region. Sixty-nine percent of respondents were informed that the websites of municipalities and executive authorities should have comprehensive information for people who want to become volunteers. The level of governmental support for volunteering measures awareness is affected by the respondents’ education. Volunteers having higher education are usually more aware of governmental support for volunteering measures and are more likely to encounter them in their activities (Gamma—0.296; p-value = 0.01).

Sixty-eight percent of the surveyed volunteers were aware of the fact that volunteers and volunteer organizations in their region can be registered, 9% believed that no volunteers were registered in their region, and 24% found it difficult to answer this question. Fifty-three percent of respondents answered yes, 19% answered no, and 28% found it difficult to answer the question whether there was a resource volunteer center in their region.

Respondents who knew about the existence of a resource volunteer center were asked to evaluate its work on a 5-point scale. The average score is 4.3 points. The resource center activity evaluation does not depend on respondent’s location, on how often they engage in volunteer work, on the organizations they help, and whether they consider themselves to be volunteers or not. The sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents also do not affect the resource centers evaluation (the criterion for assessing the significance of differences is tested by H. Kruskal–Wallis test). Significant differences, the probability of a null hypothesis with p-value ≤ 0.05, were not recorded. According to respondents familiar with the activities of volunteer resource centers, these organizations are most able to identify the problems and needs of volunteers (61%), organize interaction between volunteer organizations and civil servants (57%), and popularize volunteerism (52%). Volunteers are generally quite well informed about the institutional possibilities of coproduction of public services and appreciate positively the initiatives undertaken by the state to develop volunteering in the country.

4.3. NPOs and Volunteer Resource Centers Leaders’ Opinions on the Importance of Governmental Support for Volunteering

The analysis of the NPO leaders’ awareness level concerning government support measures to promote volunteerism at the federal and regional levels, as well as the account of these measures’ effectiveness are discussed below. Most experts are aware of the changes that have been made to the current laws regarding volunteers and their activities, 71% evaluate them positively, 15% are confident that no significant changes have occurred, 11% are not informed. Only 3% of respondents believe that the amendments changed for the worse the conditions for volunteer activities and organizations they work in.

Fifty percent of the surveyed experts noted that in their region it is possible to fully implement the initiative when volunteer activities organizers participate in the formation and activities of the coordination and consultative bodies in the field of volunteering. Thirty-eight percent of respondents say that the implementation of the initiative in their region is more of a formal nature. Expert evaluations do not differ much in relation to places and types of organizations. Fifty-nine percent of respondents are informed about the introduction of supporting volunteering national standard in the Russian Federation, and 41% do not know anything about this. Among those who are acquainted with the implementation of this initiative, 51% believe that the effect of it will be positive, and 40% find it difficult to evaluate. More than half of the experts participating in the survey noted that their organization applied for the Volunteer of Russia contest as a legal entity (63% respondents), 34% heard about the competition, but did not take part in it, and 3% declared that they were not informed about it. Experts highly evaluated the significance of the Russian Volunteer contest for the development of the volunteer movement—the average initiative rating is 4.4 out of 5 points. Experts rated the significance of “Volunteers of Russia” website with 4.1 points out of 5 (average rating). The representatives of volunteer organizations are unanimous in assessing the educational online resources of the information portal as a whole (average rating 4.4 out of 5).

The next national initiative evaluated in the study is the creation of the Association of Volunteer Centers (AVC) [

57]. Its activities are familiar to 85% of the polled experts. Respondents familiar with the activities of the AVC evaluate this organization positively. The average rating of the association is 4.3 points out of 5. The last national initiative that we asked the experts to evaluate is the events connected with the Year of the Volunteer.

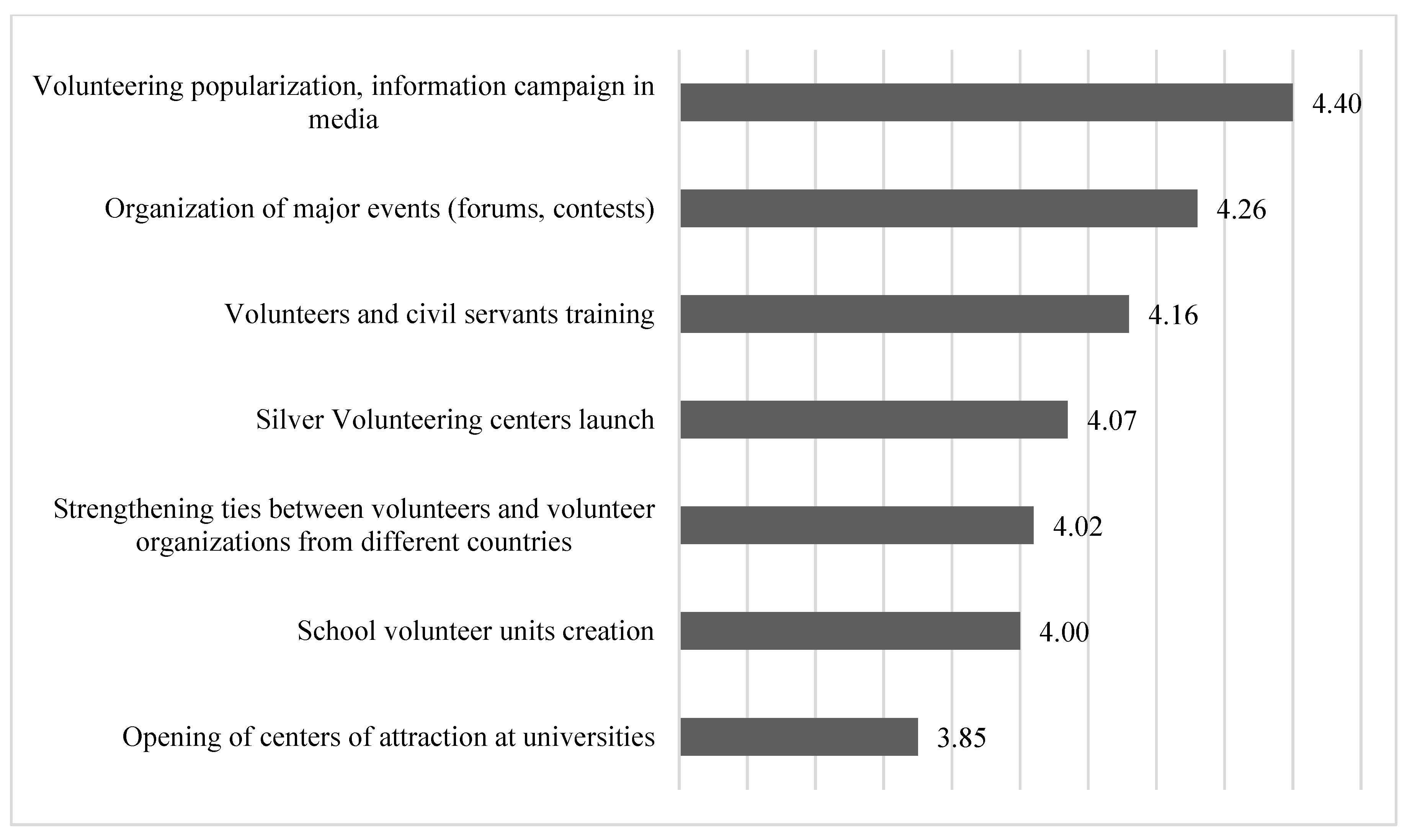

Figure 1 shows the average effectiveness estimates for nationwide events that are supported by civil servants all over Russia.

According to experts, the highest efficiency was achieved by popularizing volunteerism in the media (average rating of 4.4 out of 5) and during major events—forums, contests, etc. (average rating of 4.3 out of 5). The most ambiguous assessments were received by initiatives to open centers of attraction in universities (3.9), to create school volunteer groups (4.0), to strengthen ties with volunteer organizations in other countries (4.0), and to launch Silver Volunteering centers (4.1).

Volunteer organizations representatives are skeptical about the willingness of regional authorities to support them: the average assessment of experts is 3.6 out of 5. The resulting data do not indicate that there is a formed sense of commonality as a condition of coproduction.

Among the most likely measures taken by the local public servants the experts named the following: the opportunity to post information on the site (average rating 3.9 points), posting information in regional media (3.8 points), consultations, assistance in preparing a grant application (3.4, third place), organization of volunteer training (3.1 points), help with accommodation (3 points). Experts think that the possibility to obtain a grant or a subsidy is low (2.8 points).

More than half of the experts (52%) admit that regional civil servants give them promises, make commitments, and help solve volunteer organizations problems. Most of the events initiated by regional civil servants are aimed more at improving the image of local authorities and volunteer associations: it is volunteers being awarded with certificates of honor in 65%, or a forum, a meeting, or a conference of volunteers (60%). Civil servants are less likely to initiate volunteer campaigns (41%), train and reskill volunteers (31%), and only 28% of experts say that civil servants get acquainted with the needs of volunteer organizations.

At the same time, most experts agree that regional civil servants’ initiatives can help in developing of volunteer movement: 77% of respondents believe that such support will be noticeable, and only 23% are against such initiatives.

4.4. Governmental Support for Volunteering Actualization in Public Employees’ Assessments

Public employees were asked to evaluate the development and implementation of the Standard of Volunteer Support in Russian regions; organization and holding of the Russia-wide Volunteer of Russia contest; “Volunteers of Russia” website launch. Forty-one percent of respondents did not know anything about Volunteer Support Standard in the regions of the Russian Federation. Only 6% of the respondents turned out to be completely uninformed about the Volunteer of Russia contest, 21% heard something about it, but without any details, 54% declared to know it well, and 19% of the respondents noted that local volunteers were directly involved in the competition. About 13% of volunteers in municipalities of the Sverdlovsk Region knew nothing about the “Volunteers of Russia” website, 37% heard something about this website, and half of the respondents emphasized that they informed volunteers and helped them register on this electronic resource.

Public employees evaluated the Development of the Volunteer Movement in the Sverdlovsk Region regional program; the comprehensive work plan for the Year of the Volunteer in 2018 in the Sverdlovsk Region; the creation of the Council for the volunteerism development in the region as the measures to support the development of volunteerism at the regional level of government. Ninety-four percent of the respondents were aware of the approved regional program, and 88% of surveyed public employees knew about the comprehensive work plan for the Year of the Volunteer in 2018. About 30% of surveyed public employees did not know anything about the establishment of the Council for the volunteerism development in the Sverdlovsk region, 50% of respondents had a fairly mediocre idea on this subject—they heard something about this entity, only 21% of the respondents did not only just know about the Council, but also noted that it included the leaders of youth volunteer public organizations of their municipality.

To analyze the public employees’ attitude towards regional initiatives for supporting volunteerism in the region, respondents were asked to evaluate on a scale from 0 to 4 how regional executive authority act in support of volunteering, in their municipality. The average score for the whole sample was 2.8. The assessment regarding the chances of municipal NPOs to receive subsidies (grants) from the regional budget indicates an average score of 2.2 (out of 4). The results show that the initiatives of the federal and regional authorities, which form their key indicators and evaluate their implementation, are not perceived by municipal employees, and are not evaluated as effective practices. Again, an important element for coproduction is missing: the sense of community. The consolidation of the relevant key performance indicators (KPI) for the development of volunteering for municipal employees will help to solve the problem, but the risk of overloading local officials (instead of unloading in the concept of coproduction) and formalizing these activities increases significantly.

Next, the occurrence and specifics of providing financial, informational, event-related, and organizational support by public employees to volunteer organizations is analyzed. Financial support suggests the providing socially oriented nonprofit organizations, including volunteer organizations, with subsidies from the municipal budget on a competitive basis. Only one third of surveyed employees noted that such an opportunity is implemented for NPOs in the municipality. Below we present the respondents’ data for the types of information support provided to volunteer organizations. Seventy-six percent of public employees post information on volunteering, non-profit organizations, and their activities on the municipal administration official websites, 73%—on social networks, 71%—support information publishing in local media. 32% of public employees manage to help broadcast information on a local television channel. The information is usually spread only within the territorial limits of the city. Only 24% of respondents send information to the electronic resources of region governmental authorities, only 8% of respondents informationally communicate with the region Civil Chamber, only 6% of respondents help with posting information in the regional media. Almost none of the responsible individuals (3%) sends information about the activities and projects of local nonprofit organizations and volunteers to the federal media.

To evaluate the event-related support for volunteer organizations and communities in the regional cities, the respondents were asked the following question: “Are there any activities to popularize volunteerism in your municipality (presentations, lectures on the basis of volunteer centers and organizations, festivals, exhibitions and forums)?”. Seventy-three percent of the surveyed public employees answered that such events take place. The most popular ways to inspire volunteering activity in the region municipalities are sending letters of thanks and letters of recognition to volunteers (82%), awards for charity and volunteer activities (59%), training workshops organization (47%), and rallies, forums, or volunteering conference (46%), the latter require more significant expenses. Voluntary initiatives contests (26%) and exhibitions (23%) are less frequent in the municipalities of the Sverdlovsk region. Twenty-seven percent of the surveyed public employees said that the action plan in which people or volunteer communities could take an active part on a voluntary basis was not formed by the municipal administration, and 20% of the respondents found it difficult to answer this question.

Public employees were asked to evaluate (from 0 to 10 points) the population willingness to participate in volunteer projects and actions, and the systematic activity of educational, cultural, and social institutions of the territory. The surveyed public employees in general do not evaluate the residents’ willingness to join various volunteer practices highly, both on a one-time basis (6.6 points) and on a systematic basis (5.3 points). However, the respondents are slightly more optimistic in their assessments regarding residents’ participation in one-time volunteer projects and actions of territorial educational, cultural, and social institutions. In fact, state-led coproduction in Russia at this stage is reduced to event practices, does not lead to systemic civil self-government at the grassroots level. This shows that the state’s efforts to create an institutional environment for coproduction does not contribute to the formation of civil society (volunteers and NGOs) as an active and full participant in the joint production of social services.

Small town, townlet, and village residents’ willingness to volunteer is objectively assessed by many foreign and Russian experts as significantly lower than the willingness to volunteer for residents of larger settlements on objective (availability of external opportunities, public offers, infrastructure, etc.) and subjective (the needs of the population for the help of strangers in the presence of widespread neighborly mutual assistance) reasons.

Public servants evaluated the degree of readiness of the volunteer activities organizers (including public employees themselves) to create the necessary conditions for the activation and development of volunteering on their territory from 0 to 10. Municipal servants rated local educational, cultural, and social institutions employees’ willingness to organize social events at 7 points out of 10. The readiness of their colleagues—municipal officials—to participate in volunteer campaigns in their city was rated at 7 points, and public employee willingness to interact with NPOs within volunteering was rated at 8.2 points out of 10.

5. Conclusions

Volunteering in its global meaning is a relatively new social phenomenon for Russia, since unpaid labor was a social norm of a voluntary-compulsory nature in Soviet Russia, and volunteering was interpreted as a “bourgeois” phenomenon. At the beginning of the 21

st century, volunteering begins to revive along with the return of Christianity in Russia. Funds have been allocated purposefully from the state budget to create conditions for the development of a secular volunteer movement in the last 5 years. The 2014 Olympic Games gave volunteering a definite start when, in accordance with international standards, the Russian government began to create conditions for the development of the organized volunteering among the population. The underdeveloped volunteering movement is typical for many post-Soviet countries, and Russia is no exception. The Soviet period hindered the emergence of the nonprofit sector, which had a difficult and uneven start in the 21

st century [

7,

13]. However, the results of the study in China show that in such conditions it is possible to develop the coproduction of public services as a result of state-led initiatives. The model is vulnerable, because community initiatives remain dependent on the top-down, paternalistic type of policies that have little in common with the bottom-up approach championed by the volunteers’ movement around the world.

Under these conditions, the governmental strategy for supporting volunteering based on centralizing efforts and standardizing the activities of government civil servants in the regions and the municipalities throughout Russia described in this article is quite logical. It should be noted that such a strategy is not only a mechanism for creating the new opportunities for civic activists and their result-oriented initiatives, but also a relatively new means to achieve state goals. Widespread organized volunteer movement contributes to the formation of national identity, political power retention, and the creation of relative stability of the ruling regime. On the one hand, government and municipal employees’ effort centralization to interact with volunteer associations, the allocation of financial resources, information, and organizational support for their activities provide a certain level of volunteer associations and NPOs dependence. On the other hand, the contribution of civil and public servants and stimulating the development of this movement contributes to the people involvement in the activities of state institutions in the fields of social protection, culture, and health care, where as in many other countries resource shortages are increasingly evident.

Major events organization such as those dedicated to International Volunteer Day, country-wide volunteer contest organization, the creation of a federal website are innovations in the public sector in Russia, the significance of which is highly appreciated by the volunteers themselves, volunteering nonprofit sector leaders, and public employees directly interacting with volunteers and NPOs in their municipalities. National volunteering events and programs holding is definitely an old tradition in countries such as the United States [

58]. However, in almost all post-Soviet countries, these managerial decisions in public administration can be considered as innovative.

It is significant to note that in conditions of socio-economic uncertainty, turbulence of society, and limited resources of the state, the activities of NPOs and volunteers in ensuring the sustainable development of the territory are of particular importance. Moreover, the participation of citizens in local government, the involvement of volunteers in the implementation of state tasks, and the achievement of national development goals is a marker of the effectiveness and sustainability of public administration itself. In turn, to ensure this sustainability, it is important to create the most favorable conditions for volunteer activity of citizens, an infrastructure for supporting volunteering, considering the characteristics of the local community. Currently the task of fostering sustainable development goals under the UN vision is a matter of federal reporting, and lower levels of administration do not systematically implement measures linked to the targets formulated in the Agenda 2030 document [

59]. Once having to deal with such tasks, lower administration officials would need steering towards more energetic implementation of the partnership with NPOs and in ensuring the preconditions for citizen participation than in the current situation.

The most positively evaluated by both public servants and all interested parties is the organizational infrastructure of volunteering formed by the state, namely the establishment and development of volunteer resource centers, united in a national association. In the absence of organizational experience in this field and a poorly developed third sector, the centralization of volunteer programs and free access to educational and information resources allows innovations in working with different groups of volunteers to be developed in each Russian region and republic. This government decision makes it possible to improve volunteer management throughout the country in a relatively short period of time. It is in this innovation that the state represented by civil servants really acts as a catalyst for the prosocial activity of the population by creating the conditions for the actualization of various volunteer initiatives. It can be said that the infrastructure, opportunities for volunteers to be part of the production of public services have been created.

The main difficulty here is related to the financing of the created infrastructure. Most likely, in the absence of direct political goals (as in the Russian president’s electoral campaign of 2018), combined with a reduction of the federal funding for such issues, the regional and municipal budgets have to provide resources to maintain and keep operational, the created resource centers.

The implementation of the national Standard of Volunteer Support in the Russian regions is an innovation in the public sector, within which it will be difficult for civil servants to ignore the national strategy, at different levels of public management. However, in the conditions of rapid implementation of many managerial decisions, this particular innovation is associated with certain challenges. Empirical studies show that the most problematic areas are associated with the concerns about the formal approach to this area by regional civil servants. It is partly illustrated by the limited awareness of the introduction of such a standard by the leaders of nonprofit sector organizations and resource centers with whom civil servants should actively interact within this standard. Moreover, experts evaluate civil servants’ willingness to interact and support volunteers as low. Previous experience of lack of systemic interaction between NPO leaders and local officials does not build confidence in the state’s intentions to support volunteer projects and develop them in the context of coproductivity. Public employees who do not have volunteering experience themselves are less prepared to implement the standard. Based on the data from the Sverdlovsk region as an example, we may say that in almost half of the municipalities in the region there is no action plan to promote volunteering. In addition, the financial possibilities of regional and municipal budgets undergo cuttings. Public employee financial assistance confidence is limited, specifically the allocation of subsidies or grants curated by regional civil servants towards volunteers’ initiatives. There are practically no common municipal financial support programs for citizen’s volunteer projects. Without a proper budget support, even a positive shift in the mentality of civil servants, ready to encourage citizen participation and volunteering programs cannot resist the test of time and is doomed to waste the energy and dedication put into building partnerships for the sustainable development of the community, in a collaborative manner.

These officials underestimate the potential of the population as volunteers, able to productively produce public goods and themselves are limited in intentions of volunteering and interaction with NGOs. More than that, Russia’s experience shows that the implementation of state-led coproduction involves risks such as: (1) additional burden on local officials; and (2) high probability of reducing coproduction to event practices that do not contribute to the formation of sustainable systemic horizontal links at the local level. Responding to the research question, it is worth emphasizing that the country, on the initiative of the state, has created opportunities and institutions that allow people to play a meaningful role in the joint production of public goods and services, but there are significant limitations associated with the sense of community of all stakeholders, strong enough for people to work together to achieve common goals.

Further research on the innovations in the public sphere should evaluate the changes in the population’s attitude towards this national policy, towards the changes in the practices of regional management, specifically the interaction between civil servants and voluntary associations in the future. Another important research axis worth pursuing is the evaluation of the volunteer involvement in the activities of public sector organizations, and a comparison of these processes in the countries of the former Soviet Union with the ones in progress in the consolidated democracies of the world.