How Can Emerging Event Sustainably Develop in the Tourism Industry? From the Perspective of the S-O-R Model on a Two-Year Empirical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

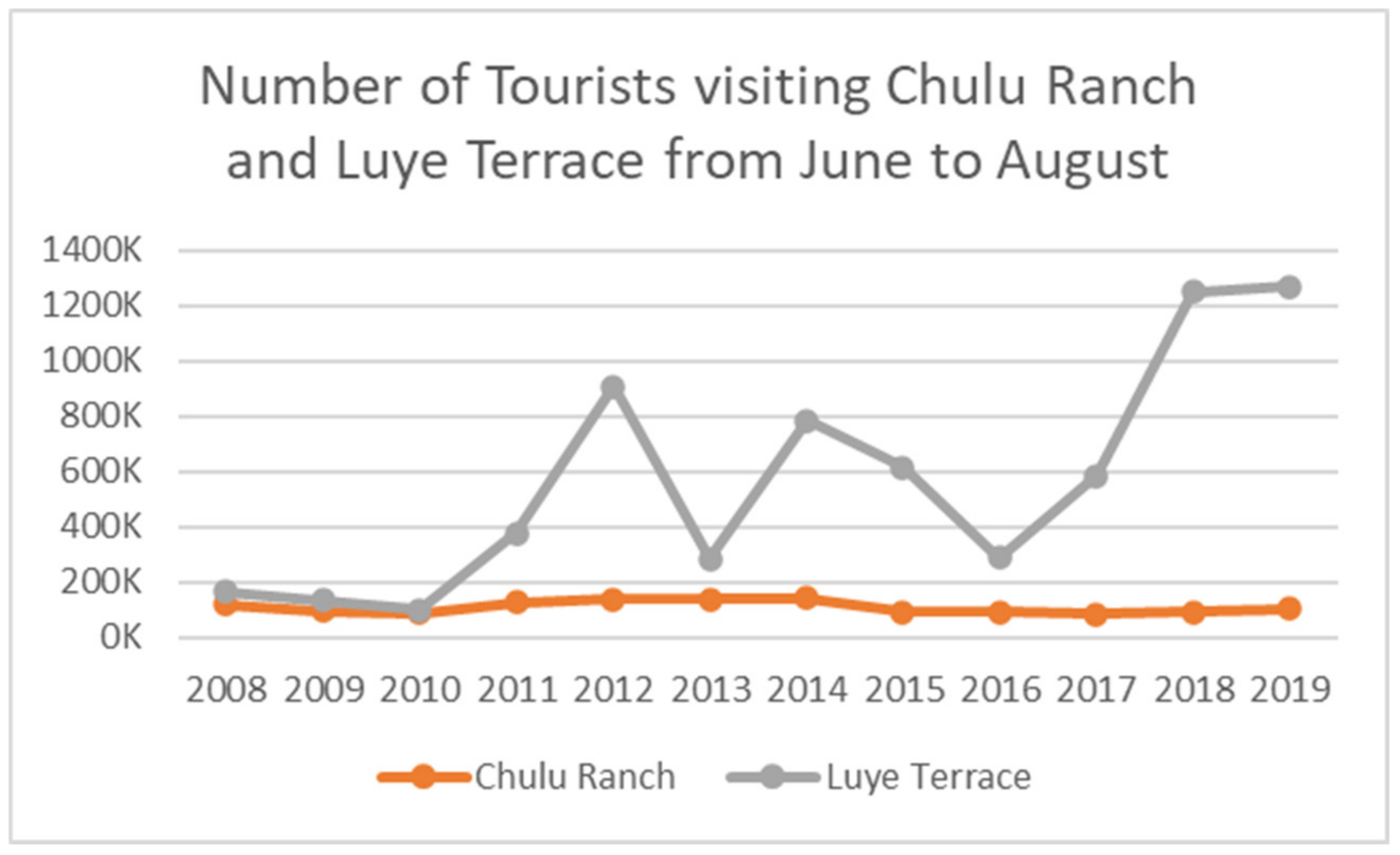

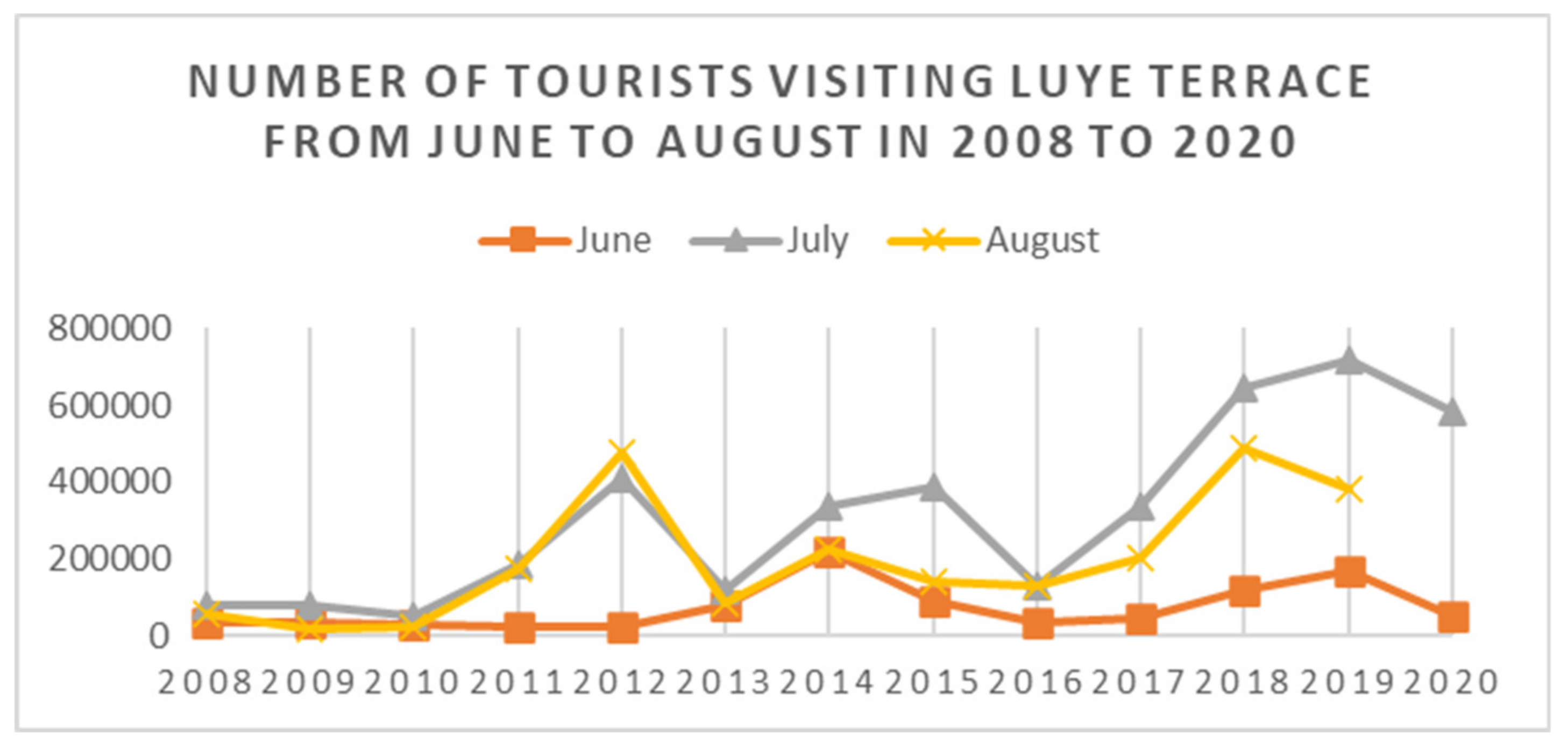

2.1. Taiwan International Balloon Festival

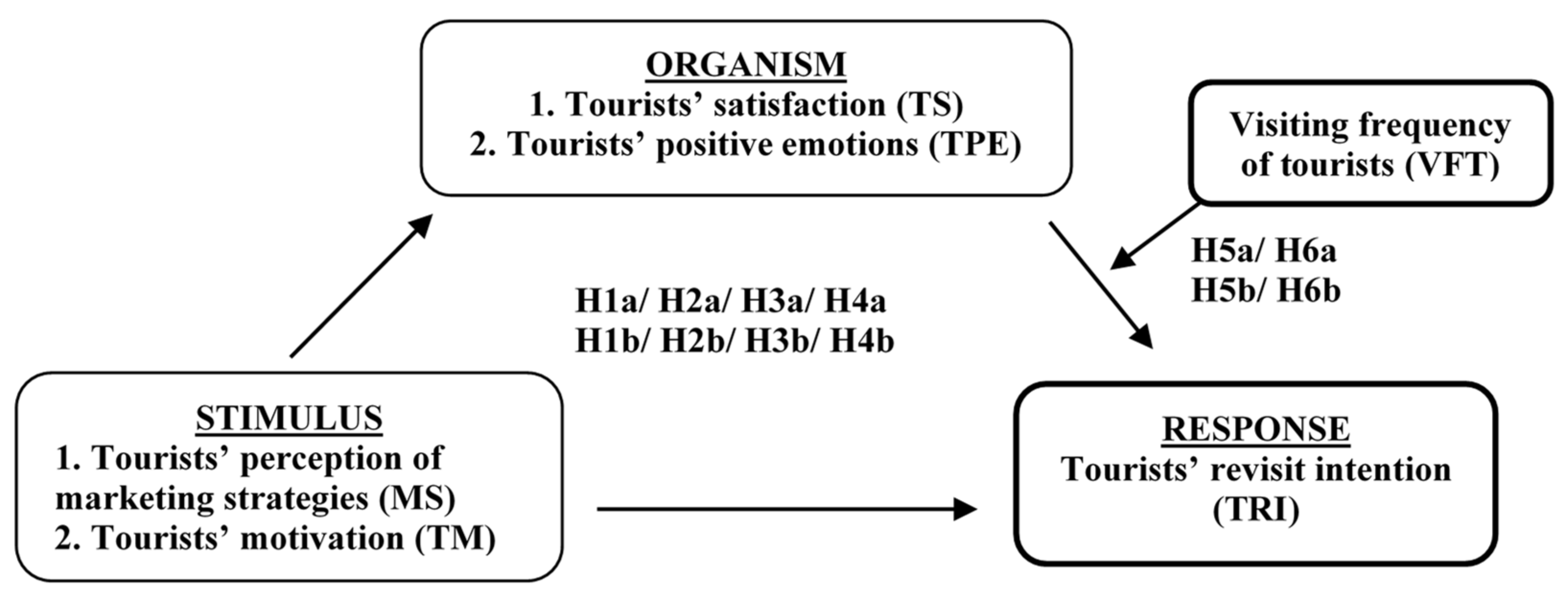

2.2. Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Model

2.3. Perception of Marketing Strategies and Motivation

2.4. Tourists’ Satisfaction and Positive Emotions

2.5. Tourists’ Revisit Intention

2.6. Mediation Effects

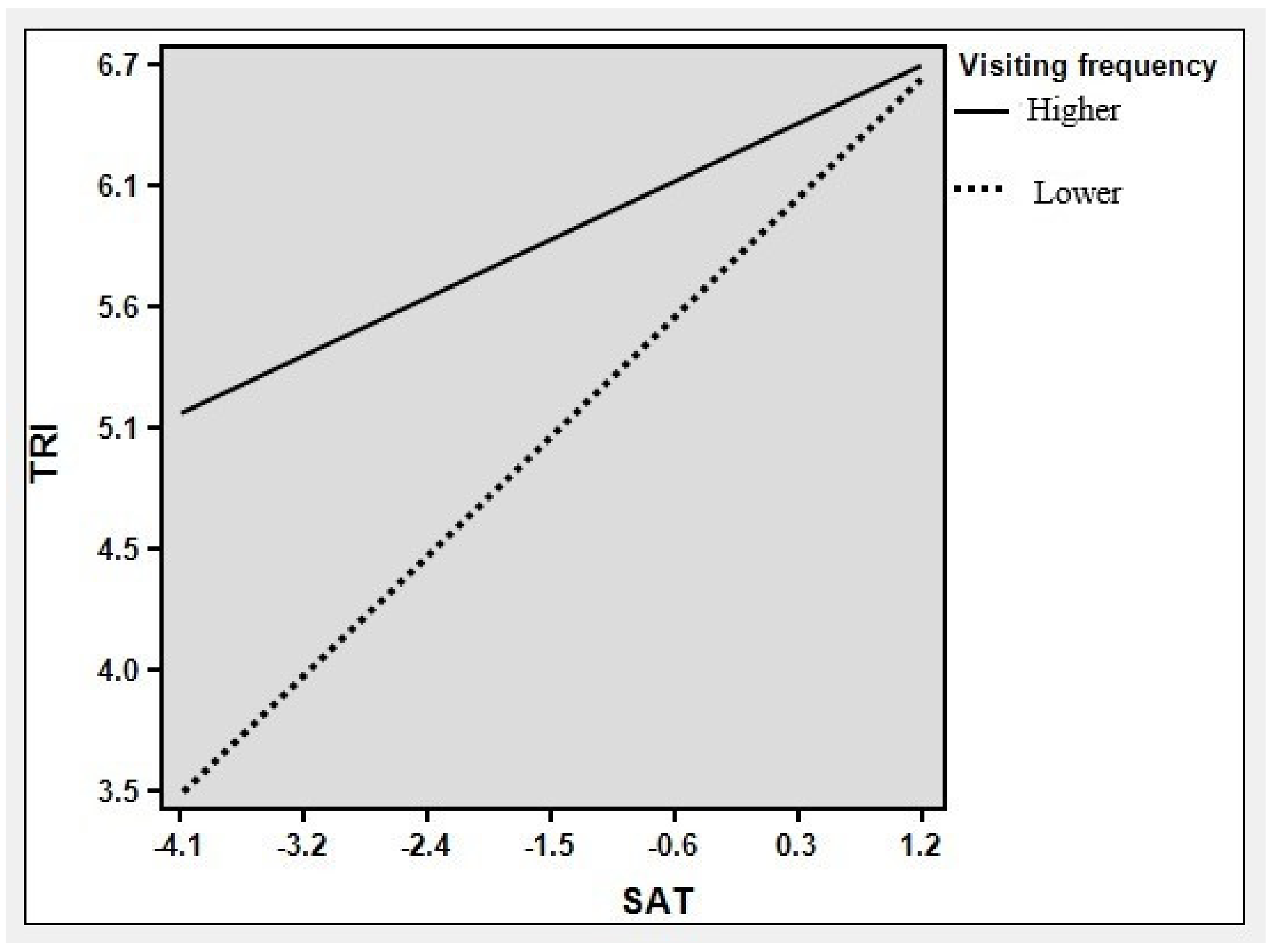

2.7. Moderation Effect of Visiting Frequency of Tourist

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Sample

4.2. Correlation, Reliability and Validity

4.3. Hypotheses Testing of Mediation Effects

4.4. Moderation Effects of Visiting Frequency of Tourist

4.5. Comparison Between 2014 and 2018

4.6. Comparison with Previous Research

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

5.2. Future Research and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, J.Z.; Li, M.; Cai, L.A. A model of community-based festival image. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Chu, C.M.; Chen, W.C. A study of policy transfer theory on analyzing hot air balloon sightseeing activities in Taiwan. J. Leis. Tour. Sport Health 2016, 6, 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhu, A.; Liu, D.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, N. Sustainability of China’s Singles Day Shopping Festivals: Exploring the Moderating Effect of Fairness Atmospherics on Consumers’ Continuance Participation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.C. How reputation creates loyalty in the restaurant sector. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Ross, M.; Shao, W. Examining the relationship between social media characteristics and psychological dispositions. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1366–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Cao, X.; Ali, A.; Masood, A.; Yu, L. Empirical investigation of Facebook discontinues usage intentions based on SOR paradigm. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Qiu, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tseng, T.H.; Zuo, L.; Hu, M. How destination music affects tourists’ behaviors: Travel with music in Lijiang, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Sarmah, B.; Gupta, S.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining branding co-creation in brand communities on social media: Applying the paradigm of stimulus-organism-response. Int. J. Info. Manag. 2018, 39, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.; King, B.E.M.; Suntikul, W. Festivalscapes and the visitor experience: An application of the stimulus organism response approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-Organism-Response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modelling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psych. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kim, Y.G. Application of the stimuli-organism-response (SOR) framework to online shopping behavior. J. Int. Commer. 2014, 13, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. The impact of perceived service fairness and quality on the behavioral intentions of Chinese hotel guests: The mediating role of consumption emotions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Principles of Marketing Management; Science Research Associates Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, Q. Making sense of a market information system for superior performance: The roles of organizational responsiveness and innovation strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D. Effects of formal institutions on the performance of the tourism sector in the Philippines: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Yang, Y.F.; Hu, Y.J.; Hsu, C.S. Marketing mix, service quality and loyalty—In perspective of customer-centric view of balanced scorecard approach. Account. Account. Perform. 2013, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gnoth, J. Motivation and expectation formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathesona, C.M.; Rimmerb, R.; Tinsley, R. Spiritual attitudes and visitor motivations at the Beltane Fire Festival, Edinburgh. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Senior travelers’ motivations and future behavioral intentions: The case of Nice. J. Travel Tour. Market. 2012, 29, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.; Suhartanto, D. The formation of visitor behavioral intention to creative tourism: The role of push–pull motivation. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Hill Inc: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M.; James, J.D. Customer satisfaction with games and service experiences: Antecedents and consequences. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 338–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Cognitive, affective and attribute bases of satisfaction response. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Namkung, Y. Perceived quality, emotions and behavioural intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S.K.; Babin, B.J. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Qu, H. The mediating role of consumption emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Nawijn, J. The impact of travel motivation on emotions: A longitudinal study. J. Destin. Market. Manag. 2020, 16, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jeong, C. Multi-dimensions of patrons’ emotional experiences in upscale restaurants and their role in loyalty formation: Emotion scale improvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Influence of environmental stimuli on hotel customer emotional loyalty response: Testing the moderating effect of the big five personality factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virto, N.R.; Punzón, J.G.; López, M.F.B.; Figueiredo, J. Perceived relationship investment as a driver of loyalty: The case of Conimbriga Monographic Museum. J. Destin. Market. Manag. 2019, 11, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Vieira, A. Destination attributes’ evaluation, satisfaction and behavioural intentions: A structural modelling approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.E.; Sanchez, M.I.; Sanchez, J. Tourism Image, Evaluation Variables and After Purchez Behavior: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grappi, S.; Montanari, F. The role of social identification and hedonism in affecting tourist re-patronizing behaviours: The case of an Italian festival. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festival scape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animesh, A.; Pinsonneault, A.; Yang, S.B.; Oh, W. An odyssey into virtual Worlds: Exploring the impacts of technological and spatial environments. MIS Q 2011, 35, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Zhao, L. What motivates customers to participate in social commerce? The impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N.A.; Vorhies, D.W.; Mason, C.H. Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 909−920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensettasilp, S.; Wu, C. Thai consumers satisfaction after receiving services from Thailand’s newest low-cost airline. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 505, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamrin, H.M. The role of service marketing mix and ship service quality towards perceived value and its impact to ship passenger’s satisfaction in Indonesia. Global J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2012, 12, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tridhoskul, P. Customers’ perception towards the service marketing mix and frequency of use of Mercedes Benz. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Econ. Bus. Eng. 2014, 8, 1945–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Assaker, G.; Reis, A. Visiting Fortaleza: Motivation, satisfaction and revisit intentions of spectators at the Brazil 2014 FIFA World Cup. J. Sport Tour. 2018, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The role of motivation in visitor satisfaction: Empirical evidence in rural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Ahn, K.; Petrick, J.F. An integrated model of festival revisit intentions: Theory of planned behavior and festival quality/ satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 818–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, H.G.; Gregory, A.; Self, J.T.; Dutta, K. Consumer behaviour in restaurants: Assessing the importance of restaurant attributes in consumer patronage and willingness to pay. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bigne´, J.E.; Mattila, A.S.; Andreu, L. The impact of experimental consumption cognitions and emotions on behavioural intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.C.; Liang, G.S. Applying fuzzy zot to explore the customer service quality to the ocean freight forwarder industry in emerging Taiwan market. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hu, C.; Wu, C.E. Affect, travel motivation, and travel intention: A senior market. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. A comparison of visitors’ motivations to attend three urban festivals. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 1995, 3, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Frías-Jamilena, D.M.; Castaeda-García, J.A.; Del Barrio-García, S. Self-congruity and motivations as antecedents of destination perceived value: The moderating effect of previous experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolal, M.; Chi, C.G.Q.; Pesämaa, O. Examine destination loyalty of first-time and repeat visitors at all-inclusive resorts. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1834–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q. An examination of destination loyalty differences between first-time and repeat visitors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavanddasht, M.; Allan, M. First-time versus repeat tourists: Level of satisfaction, emotional involvement, and loyalty at hot spring. Anatolia 2018, 30, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, A.; Mirić, R.; Drešković, N.; Hrelja, E. First-time and repeat visitors to Sarajevo. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2020, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO & UNEP. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; UNWTO, Madrid & UNEP: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of the tourist area life-cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | June | July | August | Duration | Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 32,640 | 77,014 | 55,862 | ||

| 2009 | 33,447 | 80,751 | 19,196 | ||

| 2010 | 27,689 | 48,159 | 22,140 | ||

| 2011 | 19,881 | 183,513 | 172,789 | 7/8–8/31 | 39 |

| 2012 | 23,118 | 407,483 | 477,100 | 6/29–9/2 | 66 |

| 2013 | 79,711 | 117,795 | 86,074 | 6/1–8/11 | 72 |

| 2014 | 221,130 | 339,150 | 223,832 | 5/30–8/10 | 72 |

| 2015 | 90,399 | 384,908 | 140,297 | 6/27–8/9 | 44 |

| 2016 | 33,839 | 126,446 | 126,446 | 7/1–8/7 | 38 |

| 2017 | 45,905 | 336,170 | 200,902 | 6/30–8/6 | 38 |

| 2018 | 117,386 | 643,531 | 490,003 | 6/30–8/13 | 45 |

| 2019 | 168,867 | 719,987 | 380,604 | 6/29–8/12 | 45 |

| 2020 | 52,198 | 580,650 | 7/11–8/30 | 51 |

| Variable | 2014 | 2018 | Variable | 2014 | 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 527 (100%) | n = 369 (100%) | n = 527 (100%) | n = 369 (100%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 40.4 | 44 | Riding Experience | None | 87.7 | 82.8 |

| Female | 59.6 | 55.4 | Tethered | 10.4 | 11.4 | ||

| Age | Under 20 | 15.4 | 11.7 | Free | 0.9 | 5.8 | |

| 21–30 | 41.7 | 34.3 | Companion | Alone | 3 | 4.2 | |

| 31–40 | 27.3 | 34.6 | 1 to 2 | 34.7 | 31.9 | ||

| 41–50 | 13.3 | 16.1 | 3 to 5 | 42.3 | 47.1 | ||

| Over 51 | 2.3 | 3.3 | Over 6 | 19.9 | 16.9 | ||

| Education | High school | 16.3 | 15.4 | length of stay | Half day | 8.3 | 5.5 |

| Associate | 14.4 | 15.2 | 1 day | 18.8 | 15 | ||

| Bachelor | 54.5 | 53.7 | 2 days | 34.9 | 39.3 | ||

| Master | 14.8 | 15.5 | 3 days | 38 | 40.2 | ||

| Place of residence | North | 32.1 | 28 | Transport | Bike | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Central | 14.8 | 21.3 | Motor | 19.2 | 11.4 | ||

| South | 26.2 | 23.3 | Automobile | 60.5 | 75.3 | ||

| Taitung | 14.4 | 17.7 | Bus | 9.1 | 8.6 | ||

| another east | 7.4 | 7.2 | Shuttle | 8 | 1.4 | ||

| Other | 5 | 2.5 | other | 2.3 | 2.5 | ||

| Frequency | First-time | 69.6 | 60.9 | ||||

| Revisit | 30.4 | 39.1 | |||||

| Repeat-Mean | 3.02 | 3.70 |

| Variables | α | Mean | SD | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | |||||||||

| 1. MS | 0.72 | 5.67 | 0.77 | 0.57 | (0.755) | ||||

| 2. TM | 0.84 | 5.10 | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.351 ** | (0.728) | |||

| 3. TS | 0.83 | 5.61 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.606 ** | 0.361 ** | (0.872) | ||

| 4. TPE | 0.77 | 6.20 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.441 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.497 ** | (0.905) | |

| 5. TRI | 0.88 | 5.82 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.527 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.657 ** | 0.552 ** | (0.953) |

| 2018 | |||||||||

| 1. MS | 0.68 | 5.81 | 0.74 | 0.70 | (.837) | ||||

| 2. TM | 0.89 | 5.34 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.245 ** | (.774) | |||

| 3. TS | 0.80 | 5.79 | 0.88 | 0.65 | 0.368 ** | 0.255 ** | (0.806) | ||

| 4. TPE | 0.84 | 6.30 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.257 ** | 0.106 * | 0.255 ** | (0.900) | |

| 5. TRI | 0.73 | 6.09 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.242 ** | 0.192 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.240 ** | (0.843) |

| 2014 (a) | 2018 (b) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | Model-1 | Model-2 | Model-3 | |

| H1 | TS(M1) | TRI(Y) | TRI(Y) | TS(M1) | TRI(Y) | TRI(Y) |

| MS(X) TS(M1) | a = 0.720 *** | b = 0.664 *** | b’ = 0.256 *** c = 0.566 *** | a = 0.530 *** | b = 0.369 *** | b’ = 0.148 *** c = 0.415 *** |

| H2 TM(X) TS(M1) | TS(M1) a = 0.328 *** | b = 0.349 *** | b’ = 0.138 *** c = 0.642 *** | TS(M1) a = 0.305 *** | b = 0.220 *** | b’ = 0.085 ** c = 0.443 *** |

| H3 MS(X) TPE(M2) | TPE(M2) a = 0.440 *** | b = 0.664 *** | b’ = 0.443 *** c = 0.501 *** | TPE(M2) a = 0.237 *** | b = 0.369 *** | b’ = 0.291 *** c = 0.330 *** |

| H4 TM(X) TPE(M2) | TPE(M2) a = 0.216 *** | b = 0.349 *** | b’ = 0.215 *** c = 0.618 *** | TPE(M2) a = 0.155 *** | b = 0.220 *** | b’ = 0.164 *** c = 0.363 *** |

| Mediation Paths | Bootstrap 5000 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2018 | |||||||||

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Ind.1 MS→TS→TRI Ind.2 TM→TS→TRI | 0.407 0.211 | 0.053 0.033 | 0.307 0.152 | 0.520 0.279 | 0.220 0.136 | 0.039 0.029 | 0.151 0.083 | 0.303 0.196 | ||

| Ind.3 MS→TPE→TRI Ind.4 TM→TPE→TRI | 0.220 0.134 | 0.031 0.033 | 0.164 0.070 | 0.285 0.200 | 0.078 0.056 | 0.022 0.023 | 0.041 0.018 | 0.128 0.108 | ||

| Paths | Bootstrap 5000 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Visiting Frequency as Moderator) | 2014 | 2018 | ||||||

| Coeff. | t | LLCI | ULCI | Coeff | t | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Path 1 TS→TRI | −0.016 | −0.469 | −0.083 | 0.051 | −0.054 ** | −0.268 | −0.094 | −0.015 |

| Path 2 TPE→TRI | 0.027 | 0.653 | −0.055, | 0.110 | −0.048 | 0.653 | −0.104 | 0.008 |

| Hypothesis Relationship | Validation of Hypotheses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2018 | |||

| H1: TS will mediate the relationship between MS and TRI. | H1a | V | H1b | V |

| H2: TS will mediate the relationship between TM and TRI. | H2a | V | H2b | V |

| H3: TPE will mediate the relationship between MS and TRI. | H3a | V | H3b | V |

| H4: TPE will mediate the relationship between TM and TRI. | H4a | V | H4b | V |

| H5: Visiting frequency moderates the effect of TS on TRI. | H5a | X | H5b | V |

| H6: Visiting frequency moderates the effect of TPE on TRI. | H6a | X | H6b | X |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, W.; Tsai, H.; Chuang, H.; Lin, P.; Ho, T. How Can Emerging Event Sustainably Develop in the Tourism Industry? From the Perspective of the S-O-R Model on a Two-Year Empirical Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310075

Cheng W, Tsai H, Chuang H, Lin P, Ho T. How Can Emerging Event Sustainably Develop in the Tourism Industry? From the Perspective of the S-O-R Model on a Two-Year Empirical Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310075

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Weiling, Hsientang Tsai, Hsiuhui Chuang, Paohui Lin, and Tzuya Ho. 2020. "How Can Emerging Event Sustainably Develop in the Tourism Industry? From the Perspective of the S-O-R Model on a Two-Year Empirical Study" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310075

APA StyleCheng, W., Tsai, H., Chuang, H., Lin, P., & Ho, T. (2020). How Can Emerging Event Sustainably Develop in the Tourism Industry? From the Perspective of the S-O-R Model on a Two-Year Empirical Study. Sustainability, 12(23), 10075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310075