Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX* Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR in Tourism and Hospitality

2.2. Organisational CSR and Internal Stakeholders

2.3. Employee CSR and Customer Engagement

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Context

3.2. Scale Measurements

3.3. Sample and Data Collection

4. Results and Discussion

5. Implications

5.1. Implications for Hotels and Resort Managers

5.2. Implications for Academics

5.3. Implications for Policy Makers

6. Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO Annual Report 2016. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284418725 (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development 2015, Informal Summary. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/8521Informal%20Summary%20-%20UN%20Summit%20on%20Sustainable%20Development%202015.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Hristov, D.; Ramkissoon, H. Leadership in destination management organisations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Philosophy. J. Bus Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sust. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.M. Tourism and the millennium development goals: Perspectives beyond 2015. Tour Geog. 2014, 16, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ineson, E.M.; Benke, E.; László, J. Employee loyalty in Hungarian hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Man. 2013, 32, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.R.; Mattila, A.S. Examining the spillover effect of frontline employees’ work–family conflict on their affective work attitudes and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deery, M.; Jago, L. A framework for work–life balance practices: Addressing the needs of the tourism industry. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.M.; Davis, K.D.; Crouter, A.C.; O’Neill, J.W. Understanding work-family spillover in hotel managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, C. Costing staff turnover in hospitality service organisations. J. Serv Res. 2001, 1, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A.E. Human Rights as a Dimension of CSR: The Blurred Lines Between Legal and Non-Legal Categories. J. Bus. Ethic- 2009, 88, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, G.M.; Birdie, A.K. The tourism and hospitality industry in India: Emerging issues for the next decade. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.; Bhattacharya, A. Attracting and managing talent, how are the top three hotel companies in India doing it? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Lynes, J. Corporate social responsibility in tourism and hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, R.; Rajak, K. Attitude, Motivation and barriers for csr engagement among travel and tour operators in Nepal. J. Tour. Hosp. Educ. 2020, 10, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Lund-Thomsen, P.; Jeppesen, S. SMEs and CSR in developing countries. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.N.; Messarra, L.C.; El-Khalil, R. CSR, organizational identification, normative commitment, and the moderating effect of the importance of CSR. J. Dev. Areas 2017, 51, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, S.A.; Sturman, M.C.; Raab, C. What matters more? Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Albrecht, S.L.; Leiter, M.P. Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Roy, M.J. Sustainability in action: Identifying and measuring the key performance drivers. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, C. CSR and Changing Modes of governance: Towards corporate noblesse oblige? In Corporate Social Responsibility and Regulatory Governance; Utting, P., Marques, J.C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 26–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sowamber, V.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Impact of sustainability practices on hospitality consumers’ behaviors and attitudes: The case of LUX * Resorts & Hotels. In Routledge Handbook of Hospitality Marketing; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- Dewnarain, S.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Social customer relationship management in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. 2019, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S.; Korschun, D. Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Sowamber, V. Local support in tourism in Mauritius. In Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Africa; Novelli, M., Adu-Among, M.E., Ribeiro, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Furlotti, K. The materiality assessment and stakeholder engagement: A content analysis of sustainability reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, T.; Hall, C.M.; Castka, P.; Ramkissoon, H. Migrant Workers’ Rights, Social Justice and Sustainability in Australian and New Zealand Wineries: A Comparative Context. In Social Sustainability in the Global Wine Industry; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.E.; Park, S.-Y. An analysis of CSR activities in the lodging industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardberg, N.A.; Fombrun, C.J. Corporate citizenship: Creating intangible assets across institutional environments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.G.; Kamanga, G. Drivers and barriers of corporate social responsibility in the tourism industry: The case of Malawi. Dev. South. Afr. 2020, 37, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Friess, D.A. Stakeholder preferences for payments for ecosystem services (PES) versus other environmental management approaches for mangrove forests. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasdas, W. Corporate Responsibility among international ecotourism and adventure travel operators. In Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility in Tourism; Lund-Durlacher, D., Dinica, V., Reiser, D., Fifka, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Iazzi, A.; Pizzi, S.; Iaia, L.; Turco, M. Communicating the stakeholder engagement process: A cross-country analysis in the tourism sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, N.; Smith, L.; Bickford, S.; Bice, M.R. Evaluating the role of CSR and SLO in ecotourism: Collaboration for economic and environmental sustainability of arctic resources. Resources 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Park, S.Y. An exploratory study of corporate social responsibility in the US travel industry. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supanti, D.; Butcher, K.; Fredline, L. Enhancing the employer-employee relationship through corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, V.K.; Manika, D.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Taheri, B.; McCowlen, C. Heritage tourism, CSR and the role of employee environmental behaviour. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.D.; Altinay, L.; Farmaki, A.; Gursoy, D.; Zenga, M. Consumer perceptions towards sustainable supply chain practices in the hospitality industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chathoth, P.K.; Ungson, G.R.; Harrington, R.J.; Chan, E.S. Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Altinay, L.; Chathoth, P.; Koseoglu, M.A. Strategic Management for Hospitality and Tourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Advancing the sustainable tourism agenda through strategic CSR perspectives. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Wieseke, J.; Hoyer, W.D. Social identity and the service-profit chain. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Destination marketing and visitor experiences: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Hospitality consumers’ decision-making. In Routledge Handbook of Hospitality Marketing; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, S.R.; Isabella, G.; Boaventura, J.M.G.; Mazzon, J.A. The influence of corporate social responsibility on employee satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dögl, C.; Holtbrügge, D. Corporate environmental responsibility, employer reputation and employee commitment: An empirical study in developed and emerging economies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1739–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Gao, J.H. Exploring the direct and indirect effects of CSR on organizational commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 500–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y. The consequences of employees’ perceived corporate social responsibility: A meta-analysis. Bus. Ethic- A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Heere, B.; Parent, M.M.; Drane, D. Social responsibility and the olympic games: The Mediating role of consumer attributions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasley, M.C.; Woodroof, P.J.; Coleman, J.T. Processing contradictory CSR information: The influence of primacy and recency effects on the consumer-firm relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Park, Y.E.; Song, D. Watch out when expectancy is violated: An experiment of inconsistent CSR message cueing. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, C.; Money, K.; Ghobadian, A. Unpacking the mechanism by which corporate responsibility impacts stakeholder relationships. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 24, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1979, 27, 65–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, S.S.; Akter, S.; Ahmed, M.H.U. Explaining firms’ behavioral intention towards environmental reporting in Bangladesh: An application of theory of planned behavior. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2020, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darus, F.; Sawani, Y.; Zain, M.M.; Janggu, T. Impediments to CSR assurance in an emerging economy. Manag. Audit. J. 2014, 29, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social identity theory. In Understanding Peace and Conflict through Social Identity Theory; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G. Vulnerability of nature-based tourism to climate variability and change: Case of Kariba resort town, Zimbabwe. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 29, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. A review of the IPCC Fifth assessment and implications for tourism sector climate resilience and decarbonization. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Michael Hall, C. The global effects and impacts of tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Rutty, M., Gössling, S., Scott, D., Michael Hall, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 36–62. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M. International tourism and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO Annual Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284418039 (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- McCabe, S. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith LD, G.; Weiler, B. Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Peeters, P. Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy? The costs and risks of alternate carbon reduction policy pathways. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Report 2015. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/annualreport/2015/en/index.html (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- MET Report 2017. Available online: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/news/2018/annual-state-of-the-climate-report-for-2017-now-published (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- Majeed, S.; Ramkissoon, H. Health, wellness and place attachment during and post health pandemics. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3026. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Stakeholders’ views of enclave tourism: A grounded theory approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 557–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, D.; Minocha, S.; Ramkissoon, H. Transformation of destination leadership networks. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. Pro-environmental behavior: Critical link between satisfaction and place attachment in Australia and Canada. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W.; Polonsky, M.J. The limitations and potentialities of green marketing. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2015, 27, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 Place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D. Social marketing: A systematic review of research 1998–2012. Soc. Mark. Q. 2014, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Dang, N.V.; Hall, C.M.; Dong, X.D. The internationalisation of social marketing research. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grosbois, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Joppe, M. CSR in the Tourism Industry? The Status of and Potential for Certification, Codes of Conduct and Guidelines; IFC: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. Sustaining cultural tourism through higher female participation in Nigeria: The role of corporate social responsibility in oil host communities. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Walmsley, A.; Cogotti, S.; McCombes, L.; Häusler, N. Corporate social responsibility: The disclosure–performance gap. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.; Tsang, N.K.; Cheng, S.K. Hotel employees’ perceptions on corporate social responsibility: The case of Hong Kong. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Bodwell, C.; Graves, S.B. Responsibility: The new business imperative. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriof, J.; Waddock, S. Unfolding stakeholder engagement. In Unfolding Stakeholder Thinking; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. Managing customer relationships in hotel chains: A comparison between guest and manager perceptions. In The Routledge Handbook of Hotel Chain Management; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, C.F.; Jang, S.S. The antecedents and consequences of psychological empowerment: The case of Taiwan’s hotel companies. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Levy, S. Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives of hotel frontline employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; La, S. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer trust on the restoration of loyalty after service failure and recovery. J. Serv. Mark. 2013, 27, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Laasch, O. From managerial responsibility to CSR and back to responsible management. In The Research Handbook of Responsible Management; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.H.; Scullion, H. The effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on employee motivation: A cross-national study. Pozn. Univ. Econ. Rev. 2013, 13, 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, S.D.; Terlutter, R.; Diehl, S. Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Uysal, M. Social involvement and park citizenship as moderators for quality-of-life in a national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingchi Liu, M.; Anthony Wong, I.; Rongwei, C.; Tseng, T.H. Do perceived CSR initiatives enhance customer preference and loyalty in casinos? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1024–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.W.; Sen, S.; Mota, M.D.O.; De Lima, R.C. Consumer reactions to CSR: A Brazilian perspective. J. Bus. Ethic- 2010, 91, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, S.-Y. Do socially responsible activities help hotels and casinos achieve their financial goals? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Ford, C.L. Corporate corruption and reform undertakings: A new approach to an old problem. Cornell Int. Law J. 2008, 41, 307. [Google Scholar]

- Albus, H.; Ro, H. Corporate social responsibility: The effect of green practices in a service recovery. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethic- 2013, 118, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsch, J.; Gupta, S.; Grau, S.L. A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: The mediation of work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiró, J.M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kang, J.-K.; Low, B.S. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. J. Financial Econ. 2013, 110, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 8, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epler Wood, M.; Leray, T. Corporate Responsibility and the Tourism Sector in Cambodia; Working Paper, No. 34658; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ketola, T. Do you trust your boss?—A Jungian analysis of leadership reliability in CSR. Electron. J. Bus. Ethics Organ. Stud. 2006, 11, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Idemudia, U. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.E.; Hawkins, D.E. Peace through tourism: Commerce based principles and practices. J. Bus. Ethic- 2009, 89, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, A. Corporate Futures: Social Responsibility in the Tourism Industry; Consultation On Good Practice; Tourism Concern: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.W. Corporate social responsibility in China: Window dressing or structural change. Berkeley J. Int. Law 2010, 28, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppe, R.; Forster, N.; Fox, M. A survey of managers’ perceptions of corporate ethics and social responsibility and actions that may affect companies’ success. J. Bus. Ethic- 2007, 82, 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Haysom, G. From philanthropy to a different way of doing business: Strategies and challenges in integrating pro-poor approaches into tourism business. Dev. South. Afr. 2006, 23, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso Castro, C.; Martín Armario, E.; Martín Ruiz, D. The influence of employee organizational citizenship behavior on customer loyalty. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, M.; Peters, M. Hospitality managers’ perception of corporate social responsibility: An explorative study. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.; Swain, S.D. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, C.A. Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: Effects of community outreach on members’ organizational identity and identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewnarain, S.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Social customer relationship management: An integrated conceptual framework. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makower, J. Beyond the Bottom Line; Simon: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Bitner, M.J.; Gremler, D. Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus across the Firm; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Mackenzie, M.; Prideaux, B.; Pang, S. Is the hospitality and tourism curriculum effective in teaching personal social responsibility? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soron, D. Sustainability, self-identity and the sociology of consumption. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Mowen, J.C.; Donavan, D.T.; Licata, J.W. The Customer Orientation of Service Workers: Personality Trait Effects on Self-and Supervisor Performance Ratings. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Gursoy, D. Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Jones, K.C. Employee performance cues in a hotel service environment: Influence on perceived service quality, value, and word-of-mouth intentions. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 35, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Heo, C.Y. Corporate social responsibility and customer satisfaction among US publicly traded hotels and restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A. Customer delight: Distinct construct or zone of nonlinear response to customer satisfaction? J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.; Rust, R.; Varki, S. Customer delight: Foundations, findings, and managerial insight. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Proenvironmental behavior: The link between place attachment and place satisfaction. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.N.; Kline, S. From customer satisfaction to customer delight. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 642–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.N.; Milman, A.; Park, S. Delighted or outraged? Uncovering key drivers of exceedingly positive and negative theme park guest experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2018, 1, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Olshavsky, R.W.; King, M.F. Exploring alternative antecedents of customer delight. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 2001, 14, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Crotts, J.C.; Magnini, V.P. The customer delight construct. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.; Matzler, K.; Faullant, R. Asymmetric effects in customer satisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1159–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The consumption of tourism. Sociology 1990, 24, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. The effects of perceived authenticity, information search behaviour, motivation and destination imagery on cultural behavioural intentions of tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 537–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhshik, A.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Ramkissoon, H. Industrialization of Nature in the Time of Complexity Unawareness: The Case of Chitgar Lake, Iran. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Waddock, S. Parallel universes: Companies, academics, and the progress of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2004, 109, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. The satisfaction–place attachment relationship: Potential mediators and moderators. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H.; Gursoy, D. Use of structural equation modeling in tourism research: Past, present, and future. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 28, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethic- A Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Malgeri Manzo, R.; Covino, D. Consumer behavior and corporate social responsibility: An evaluation by a choice experiment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, M.; Kemperman, A.; Dolnicar, S. Making cause-related corporate social responsibility (CSR) count in holiday accommodation choice. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, P.M.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z. Consumer social responses to CSR initiatives versus corporate abilities. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomering, A.; Dolnicar, S. Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: Are consumers aware of CSR initiatives? J. Bus. Ethic- 2009, 85, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, K.J.; Farache, F.; Shukla, P.; Berry, A. Communicating responsibility-practicing irresponsibility in CSR advertisements. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E. CSR practices and consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Gendered theory of planned behaviour and residents’ support for tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.R.; Smith LD, G. The relationship between environmental worldviews, emotions and personal efficacy in climate change. Int. J. Arts Sci. 2014, 7, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, S.; Wæraas, A. CSR-washing is rare: A conceptual framework, literature review, and critique. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Jai, T.M. Waste less, enjoy more: Forming a messaging campaign and reducing food waste in restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Integrating and unifying competing and complementary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Bus. Soc. 2008, 47, 148–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in Scandinavia: An overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, L.; Gaither, B.M. Perceived motivations for corporate social responsibility initiatives in socially stigmatized industries. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. The obfuscation of gender and feminism in CSR research and the academic community: An essay. In Gender Equality and Responsible Business; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

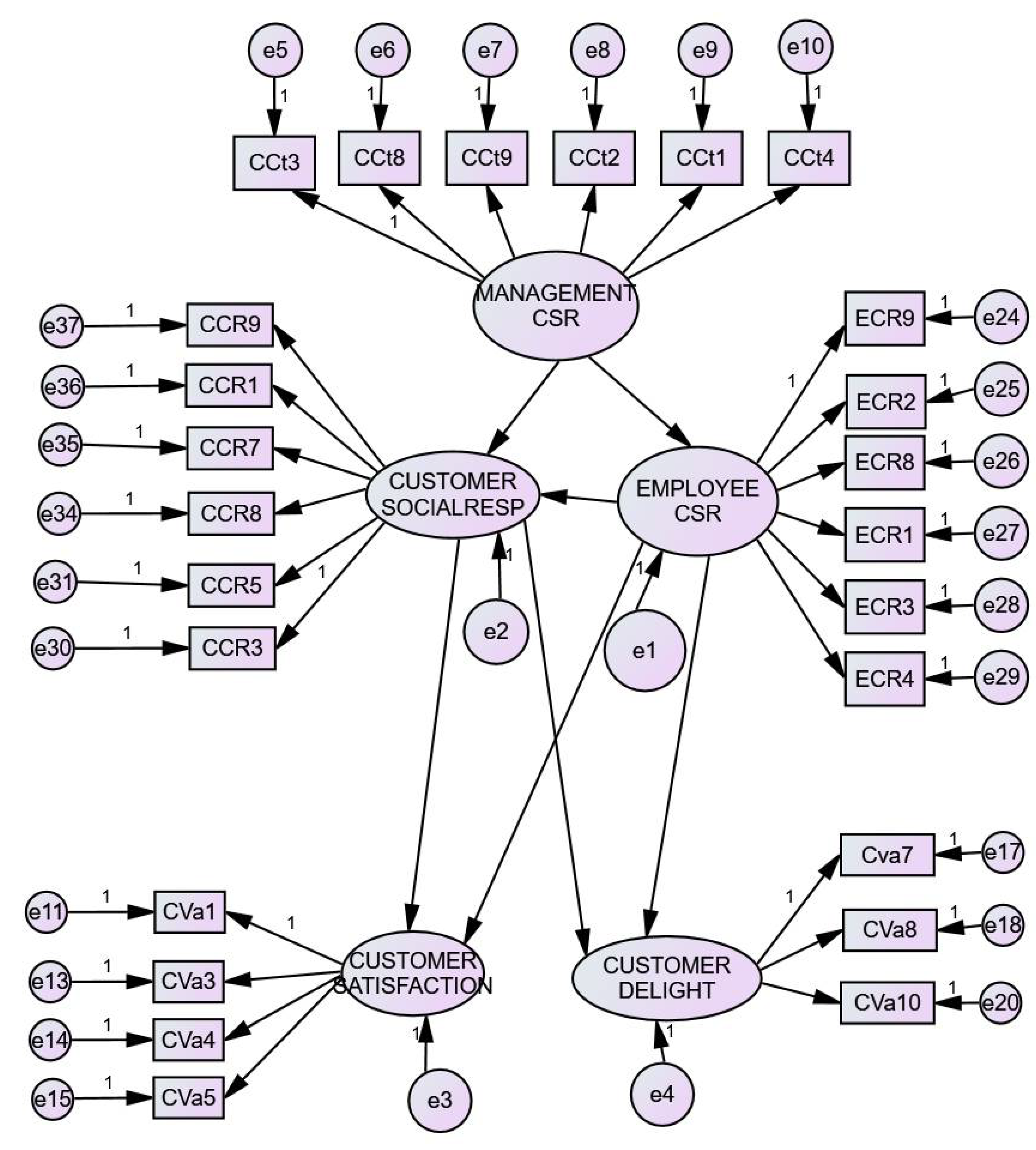

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Management CSR | 0.689 | ||||

| 2. Employee CSR | 0.043 | 0.652 | |||

| 3. Customer Social Responsibility | −0.133 ** | −0.156 ** | 0.712 | ||

| 4. Customer Satisfaction | 0.084 | −0.194 ** | 0.840 ** | 0.693 | |

| 5. Customer Delight | 0.028 | −0.126 ** | 0.310 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.723 |

| Internal Consistency | 0.848 | 0.818 | 0.864 | 0.788 | 0.768 |

| Cronbach alpha | 0.828 | 0.812 | 0.864 | 0.803 | 0.667 |

| Skewness | −1.069 | −0.733 | 2.485 | 2.576 | 2.376 |

| Kurtosis | 1.015 | −0.646 | 2.285 | 2.844 | 2.226 |

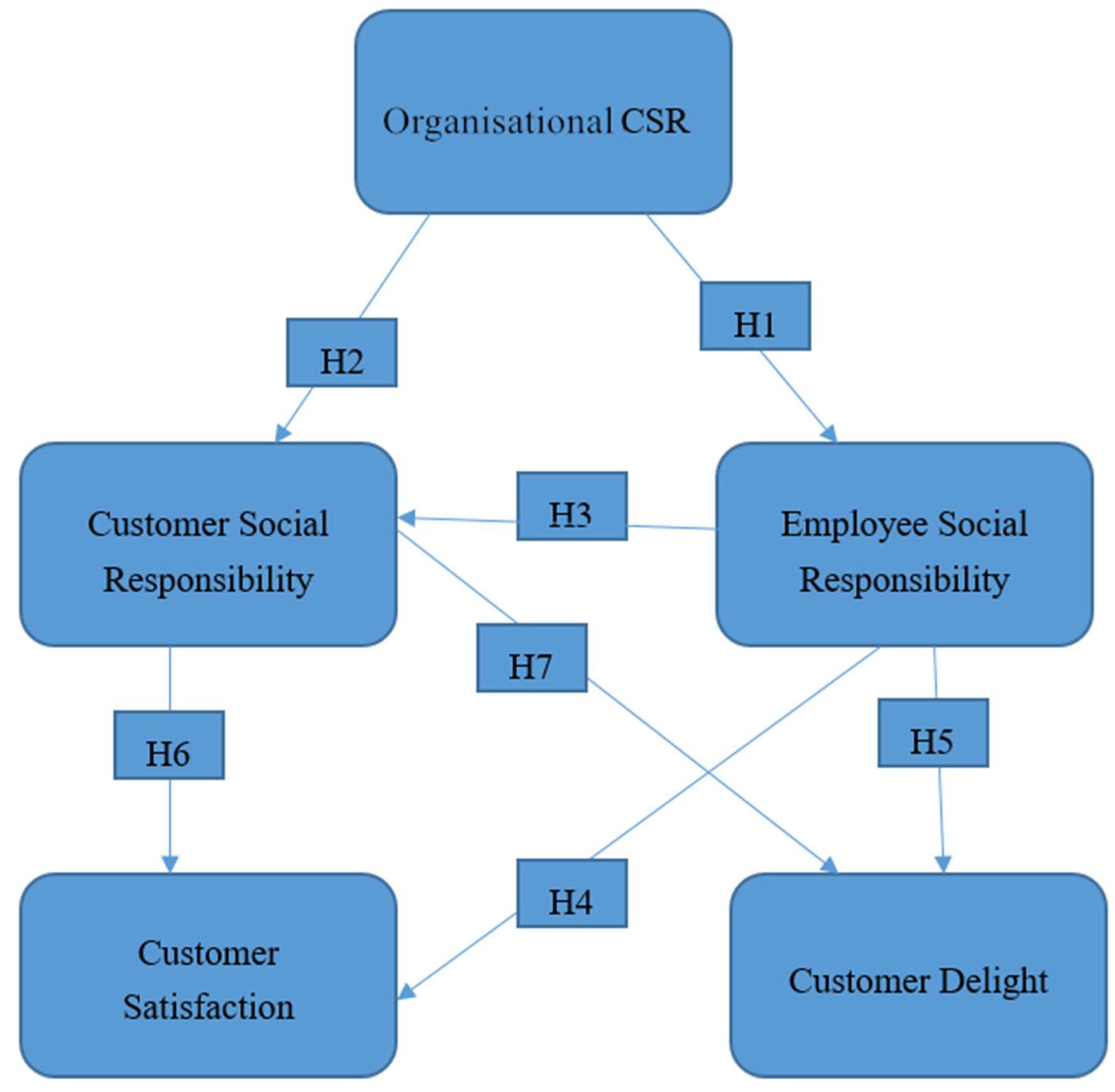

| Hypothesis | Standardized Regression (β) | t-Value | Supported/Not Supported |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Organizational CSR is positively related to Employee social responsibility | 0.133 | 2.345 * | Supported |

| H2: Organizational CSR is positively related to Customer social responsibility | −0.144 | −2.624 ** | Not supported |

| H3: Employee Social responsibility is positively related to customer social responsibility | −0.182 | −3.257 *** | Not supported |

| H4: Employee Social responsibility is positively related to customer satisfaction | −0.024 | −0.727 | Not supported |

| H5: Employee Social responsibility is positively related to customer delight | −0.0127 | −2.134 * | Not supported |

| H6: Customer social responsibility is positively related to customer satisfaction | 0.869 | 12.430 *** | Supported |

| H7: Customer social responsibility is positively related to customer delight | 0.299 | 4.842 *** | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.; Sowamber, V. Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX* Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229745

Ramkissoon H, Mavondo F, Sowamber V. Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX* Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229745

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamkissoon, Haywantee, Felix Mavondo, and Vishnee Sowamber. 2020. "Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX* Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229745

APA StyleRamkissoon, H., Mavondo, F., & Sowamber, V. (2020). Corporate Social Responsibility at LUX* Resorts and Hotels: Satisfaction and Loyalty Implications for Employee and Customer Social Responsibility. Sustainability, 12(22), 9745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229745