A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

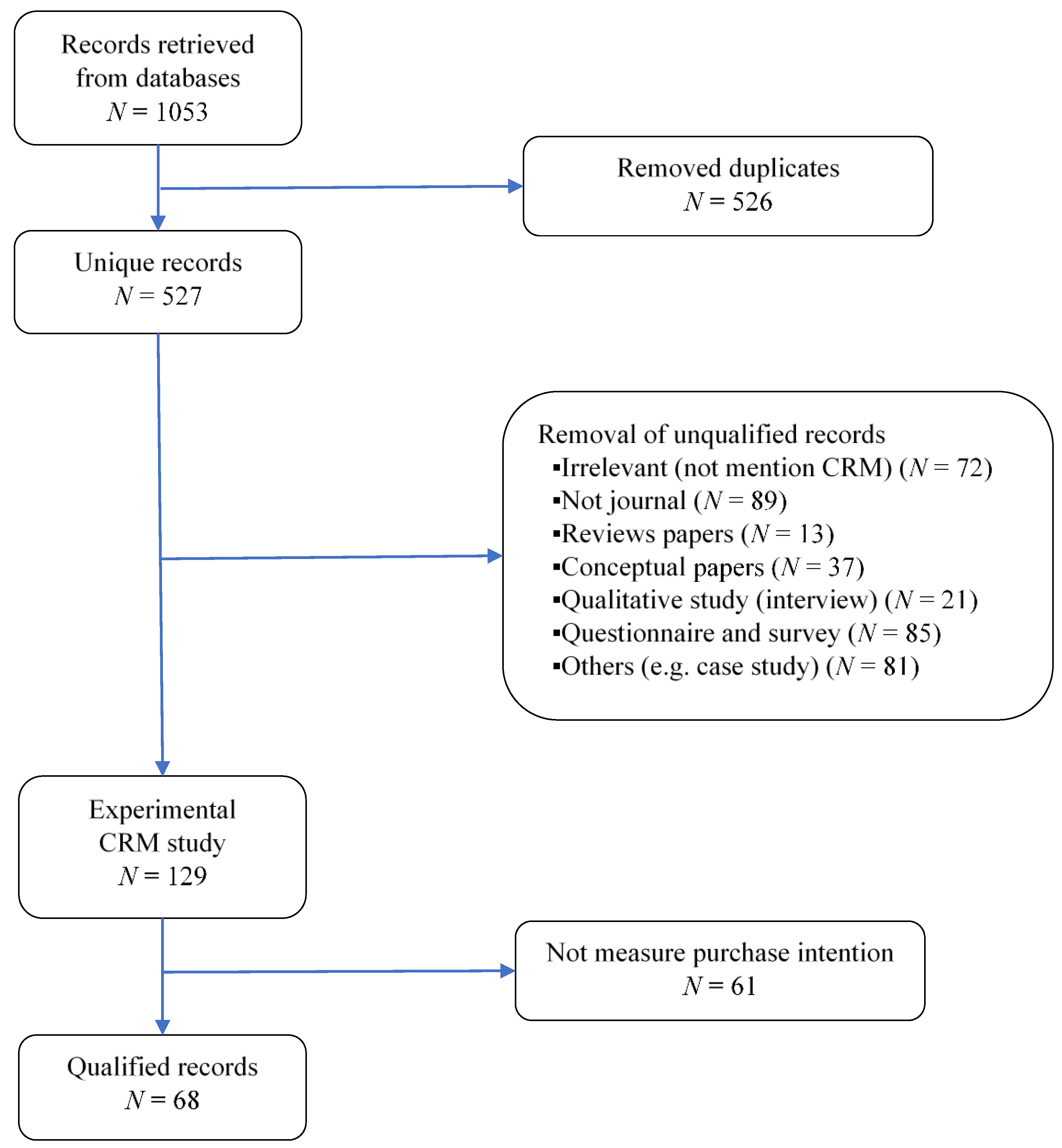

2. Materials and Methods

cause-related marketing * or cause-brand alliance * or charity-linked brand * or product charity bundle * AND experiment * or trial * or study * or questionnaire * or survey *

- Study characteristics, including experiment locations, theory used, sample size, etc.

- Experiment conditions, including product types, whether the company/brand is fictitious, the social causes, and the donation size.

- Experimental variables, including all kinds of independent variables (the determinants of PI, such as brand awareness, company motivation, message framing, etc.), dependent variables (other than PI), any moderators/mediators (if any), as well as the effects on PI.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Determinants and Effects on PI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, M.P. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: It’s evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.M.M.; Fellows, R.; Tuuli, M.M. The role of corporate citizenship values in promoting corporate social performance: Towards a conceptual model and a research agenda. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2011, 29, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H. Consumer socially sustainable consumption: The perspective toward corporate social responsibility, perceived value, and brand loyalty. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 13, 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, D.; Gupta, A.; Sagar, M. Effectiveness of cause-related marketing for differential positioning of market entrant in developing market: An exploratory study in Indian context. Int. J. Nonprof. Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2017, 22, e1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroof, P.J.; Deitz, G.D.; Howie, K.M.; Evans, R.D. The effect of cause-related marketing on firm value: A look at Fortune’s most admired all-stars. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 899–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzaee, H.K.; Sadeghian, M.; Jalalian, S. Which can affect more? Cause marketing or cause-related marketing. J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 10, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Reast, J.; Van Popering, N. To do well by doing good: Improving corporate image through cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šontaitė-Petkevičienė, M.; Grigaliūnaitė, R. The use of cause-related marketing to build good corporate reputation? Organizacijų Vadyba 2020, 83, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosmayer, D.C.; Fuljahn, A. Consumer perceptions of cause related marketing campaigns. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston-Heyes, C.; Liu, G. A study of non-profit organisations in cause-related marketing. Eur. J. Market. 2013, 47, 1954–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Chu, X.Y. The give and take of cause-related marketing: Purchasing cause-related products license consumer indulgence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Scodellaro, A.; Pang, B.; Lo, H.Y.; Xu, Z. Attribution and effectiveness of cause-related marketing: The interplay between cause-brand fit and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.; Hechtman, J. Corporate sponsorships of sports and entertainment events: Considerations in drafting a sponsorship management agreement. Marquette Sports Law Rev. 2000, 11, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.T.; Duff, B.R.L.; Vargas, P.; Himelboim, I.; Sundaram, H. Can we find the right balance in cause-related marketing? Analyzing the boundaries of balance theory in evaluating brand-cause partnerships. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Kim, H. Temporal duration and attribution process of cause-related marketing: Moderating roles of self-construal and product involvement. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Koritos, C.D.; Krepap, A.; Tasoulis, K.; Theodorakis, I.G. Containing cause-related marketing skepticism: A comparison across donation frame types. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2016, 19, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Edmondson, D.R. A note on the role of cause type in cause-related marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Gabrielli, V. Brand prominence in cause-related marketing: Luxury versus non-luxury. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Lueth, A.K.; McCafferty, R. An evolutionary process model of cause-related marketing and systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.O.; AbouAish, E.M. The impact of strategic vs. tactical cause-related marketing on switching intention. Int. Rev. Public NonProfit Mark. 2018, 15, 253–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pirsch, J. A Taxonomy of cause-related marketing research: Current findings and future research directions. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Mark. 2006, 15, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Rita, P.; Trigueiros, D. A text mining-based review of cause-related marketing literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 139, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Kureshi, S.; Vatavwala, S. Cause-related marketing research (1988–2016): An academic review and classification. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Mark. 2019, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhfeld, W.F.; Tobias, R.D.; Garratt, M. Efficient experimental design with marketing research applications. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews; Joint Technical Report, Keele University technical report TR/SE-0401; National ICT Australia Technical Report 0400011T.1; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004; ISSN 1353-7776. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Skallerud, K. Asystematic review of the trade show marketing literature: 1980-2014. Ind. Market. Manag. 2017, 63, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubacki, K.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Pang, B.; Buyucek, N. Minimizing alcohol harm: A systematic social marketing review (2000–2014). J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T. Missing ingredients in cause-related advertising: The right formula of execution style and cause framing. Int. J. Advert. 2012, 31, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, D.Y. Exploring the effective restaurant CrM ad: The moderating roles of advertising types and social causes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2473–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Stefan, I.V.; Hoyer, W.D. Willingness to pay for cause-related marketing: The impact of donation amount and moderating effects. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Huang, Y.H. Cause-related marketing is not always less favorable than corporate philanthropy: The moderating role of self-construal. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakhani, H.; Carvalho, S.W.; Cunningham, P.H. When partners divorce: Understanding consumers’ reactions to partnership termination in cause-related marketing programs. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Henderson, T. Embedded premium promotion: Why it works and how to make it more effective. Mark. Sci. 2007, 26, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M. Effects of various types of cause-related marketing (CRM) ad appeals on consumers’ visual attention, perceptions, and purchase intentions. J. Promot. Manag. 2016, 22, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Antonetti, P. High-fit charitable initiatives increase hedonic consumption through guilt reduction. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 2030–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Gabrielli, V. Co-branded cause-related marketing campaigns: The importance of linking two strong brands. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2013, 10, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghi, I.; Gabrielli, V. For-profit or non-profit brands: Which are more effective in a cause-related marketing programme? J. Brand Manag. 2013, 20, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Miyazaki, A.D.; Taylor, K.A. The influence of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: Does one good turn deserve another? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Norman, A.T.; Miyazaki, A.D. Consumer response to retailer use of cause-related marketing: Is more fit better? J. Retail. 2007, 83, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, S.; Jere, M.G. Cause-related marketing in an emerging market: Effect of cause involvement and message framing on purchase intention. J. Database Mark. Customer Strategy Manag. 2012, 19, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boenigk, S.; Schuchardt, V. Cause-related marketing campaigns with luxury firms: An experimental study of campaign characteristics, attitudes, and donations. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sector Mark. 2013, 18, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T. Guilt appeals in cause-related marketing: The subversive roles of product type and donation magnitude. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 587–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T. To donate or not to donate? Product characteristics and framing effects of cause-related marketing on consumer purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Chen, P.C.; Chu, X.Y.; Kung, M.T.; Huang, Y.F. Is cash always king? Bundling product-cause fit and product type in cause-related marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Su, S.; He, F. Does cause congruence affect how different corporate associations influence consumer responses to cause-related marketing? Aust. J. Manag. 2014, 39, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Seo, S. Goodwill intended for whom? Examining factors influencing conspicuous prosocial behavior on social media. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 60, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Seo, S. When a stigmatized brand is doing good? The role of complementary fit and brand equity in cause-related marketing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3447–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Trent, E.S.; Sullivan, P.M.; Matiru, G.N. Cause-related marketing: How generation Y responds. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Guha, A.; Biswas, A.; Krishnan, B. How product-cause fit and donation quantifier interact in cause-related marketing (CRM) settings: Evidence of the cue congruency effect. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elving, W.J.L. Scepticism and corporate social responsibility communications: The influence of fit and reputation. J. Mark. Commun. 2013, 19, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Grau, S.L.; Moulard, J.G.; Pounders, K. Cause-related marketing: Factors promoting campaign evaluations. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2014, 35, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folse, J.A.G.; Niedrich, R.W.; Grau, S.L. Cause-relating marketing: The effects of purchase quantity and firm donation amount on consumer inferences and participation intentions. J. Retail. 2010, 86, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, S.L.; Folse, J.A.G. Cause-related marketing (CRM): The influence of donation proximity and message-framing cues on the less-involved consumer. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H.; Patrick, V.M. Gilt and guilt: Should luxury and charity partner at the point of sale? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjat, M.M. Effects of cause-related marketing on attitudes and purchase intentions: The moderating role of cause involvement and donation size. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Mark. 2003, 11, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, A. One for me, one for you: Cause-related marketing with buy-one give-one promotions. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, R.P.; Wilson, T. The impact of cause branding on consumer reactions to products: Does product/cause ’fit’ really matter? J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.W.; Zhu, W.C.; Gouran, D.; Kolo, O. Moral identity centrality and cause-related marketing: The moderating effects of brand social responsibility image and emotional brand attachment. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, K.M.; Yang, L.F.; Vitell, S.J.; Bush, V.; Vorhies, D. Consumer participation in cause-related marketing: An examination of effort demands and defensive denial. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Fitzpatrick, J. Lending a hand: Perceptions of green credit cards. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1329–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, D.; Terblanche, N. Who receives what? The influence of the donation magnitude and donation recipient in cause-related marketing. J. Nonprofit Public Sector Mark. 2012, 24, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicic, J.; Baxter, S.M.; Kulczynski, A. Keeping it real: Examining the influence of co-branding authenticity in cause-related marketing. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A.H.; Das, N. Thinking about fit and donation format in cause marketing: The effects of need for cognition. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2013, 21, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, J.; Florack, A.; Chladek, A. How to present donations: The moderating role of numeracy in cause-related marketing. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Huber, I.V.; Hoyer, W.D. When will price increases associated with company donations to charity be perceived as fair? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kull, A.J.; Heath, T.B. You decide, we donate: Strengthening consumer-brand relationships through digitally co-created social responsibility. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, A.; Rice, D.H. The impact of perceptual congruence on the effectiveness of cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Consum.Psychol. 2015, 25, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. The relevance of fit in a cause-brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate credibility. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A. Selecting the right cause partners for the right reasons: The role of importance and fit in cause-brand alliances. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ferreira, M. A role of team and organizational identification in the success of cause-related sport marketing. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives on consumers’ identification with companies. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Lii, Y.S.; Lee, M. Doing right leads to doing well: When the type of csr and reputation interact to affect consumer evaluations of the firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S.; Wu, K.W.; Ding, M.C. Doing good does good? Sustainable marketing of csr and consumer evaluations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, E.; Youn, S.; Yoon, D. Functional matching effect in CRM: Moderating roles of perceived message quality and skepticism. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, I.; Montaner, T. Cause-related marketing: An experimental study about how the product type and the perceived fit may influence the consumer response. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2016, 25, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendini, M.; Peter, P.C.; Gibbert, M. The dual-process model of similarity in cause-related marketing: How taxonomic versus thematic partnerships reduce skepticism and increase purchase willingness. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 91, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Cornwell, T.B. The cause cue effect: Cause-related marketing and consumer health perceptions. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 372–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizerski, D.; Mizerski, K.; Sadler, O. A field experiment comparing the effectiveness of “Ambush” and cause related ad appeals for social marketing causes. J. Nonprof. Public Sector Mark. 2001, 9, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.R.; Vilela, A.M. Exploring the interactive effects of brand use and gender on cause-related marketing over time. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sector Mark. 2017, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.D.; Pracejus, J.W.; Brown, N.R. When profit equals price: Consumer confusion about donation amounts in cause-related marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2003, 22, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.R.; Irmak, C.; Jayachandran, S. Choice of cause in cause-related marketing. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, O. The detrimental effect of cause-related marketing parodies. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 517–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, S.; Wymer, W. The effect of fit and dominance in cause marketing communications. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; Reinhard, M.A.; Grunewald, F.; Messner, M. ‘I want to persuade you!’ Investigating the effectiveness of explicit persuasion concerning attributes of the communicator and the marketing campaign. Soc. Influ. 2017, 12, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, A.; Ferguson, D.; Beise-Zee, R. How to go green: Unraveling green preferences of consumers. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 7, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangari, A.H.; Folse, J.A.G.; Burton, S.; Kees, J. The moderating influence of consumers’ temporal orientation on the framing of societal needs and corporate responses in cause-related marketing campaigns. J. Advert. 2010, 39, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.M.; Rifon, N.J.; Lee, E.M.; Reece, B.B. Consumer receptivity to green ads: A test of green claim types and the role of individual consumer characteristics for green ad response. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, R.; Aggarwal, P.; Kozłowski, W. Interdependent self-construal in collectivist cultures: Effects on compliance in a cause-related marketing context. J. Mark. Commun. 2013, 19, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Quaquebeke, N.; Becker, J.U.; Goretzki, N.; Barrot, C. Perceived ethical leadership affects customer purchasing intentions beyond ethical marketing in advertising due to moral identity self-congruence concerns. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 156, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, A.M.; Nelson, M.R. Testing the selectivity hypothesis in cause-related marketing among generation Y: [When] Does gender matter for short- and long-term persuasion? J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, J.; Basil, D.Z.; Runté, M. Psychological distance and perceived consumer effectiveness in a cause-related marketing context. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2017, 14, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Kim, J.A.; Doh, S.J. The dual processing of donation size in cause-related marketing (CRM): The moderating roles of construal level and emoticons. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hanks, L.; Line, N. The joint effect of power, relationship type, and corporate social responsibility type on customers’ intent to donate. J. Hosp. Tourism Res. 2019, 43, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. McGraw-Hill Series in Social Psychology: Social Cognition, 2nd ed.; Mcgraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 313–339. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Hovland, C.I., Kelley, H.H., Janis, I.L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Farache, F.; Perks, K.J.; Wanderley, L.S.O.; Filho, J.M.S. Cause related marketing: Consumers’ perceptions and benefits for profit and non-profits organisations. Braz. Adm. Rev. 2008, 5, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File, K.M.; Prince, R.A. Cause related marketing and corporate philanthropy in the privately held enterprise. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lélé, S.M. Sustainable development: A critical review. World Dev. 1991, 19, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, M.; Vrontis, D.; Leonidou, E.; Thrassou, A. Customer engagement through choice in cause-related marketing: A potential for global competitiveness. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 37, 621–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Number of Articles Retrieved |

|---|---|

| EBSCO (Scholarly Journals) | 292 |

| Emerald | 0 |

| Ovid | 144 |

| ProQuest (All databases) | 372 |

| Web of Science | 245 |

| Total | 1053 |

| No. | Lead Author, Year | Location | Theory(s) Used | Product Type(s) | Company | Cause Type(s) | Donation Type/Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aghakhani, 2019 (S1) [36] | Canada | N/A | Orange juice | Fictitious | Humanitarian aid, health | USD 0.5 per sale |

| 1 | Aghakhani, 2019 (S2) [36] | Canada | Attribution | Orange juice | Fictitious | Humanitarian aid, health | 5% of sales |

| 2 | Arora, 2007 (S1) [37] | USA | Utility theory | Bottled water | True, fictitious | N/A | USD 0.15, 0.30, 0.45 per sale |

| 2 | Arora, 2007 (S2) [37] | USA | N/A | Bottled water | True, fictitious | N/A | USD 0.15 per sale |

| 3 | Bae, 2016 [38] | USA | ELM, perceptual fluency theory | Shampoo | Fictitious | Environmental | USD 1 per sale |

| 4 | Baghi, 2017 (S1) [39] | Italy | Rational choice, information integration theory | Sunglasses, printer, massage coupon, train transit pass | N/A | Health | 5% of price |

| 4 | Baghi, 2017 (S2) [39] | Italy | Perceptual fluency, associative theory | Dental check-up, paper napkins, massage coupon, ice cream | N/A | Health, food/nutrition, Humanitarian aid | 5% of price |

| 5 | Baghi, 2013a [40] | Italy | Signaling theory | Pen | True | Educational | 5% of sales |

| 6 | Baghi, 2013b [41] | Italy | Signaling theory | Doll | True | Humanitarian aid | 5% of sales |

| 7 | Baghi, 2018 (S1) [19] | Italy | Signaling theory | Mug, notebook | True | Humanitarian aid | 5% of sales |

| 7 | Baghi, 2018 (S2) [19] | Italy | Signaling theory | Chocolate | True | Humanitarian aid | 5% of sales |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S1a) [42] | USA | PKM | Television | Fictitious | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S1b) [42] | USA | PKM | Television | Fictitious | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S2a) [42] | USA | Utility theory | PC | Fictitious | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S2b) [42] | USA | Expectancy value model | PC | Fictitious | N/A | N/A |

| 9 | Barone, 2007 (S2) [43] | USA | Consistency theory | Pet supply, drugstore | Fictitious | Health | N/A |

| 9 | Barone, 2007 (S3) [43] | USA | Information integration | Pharmaceutical products | Fictitious | Animal, health | N/A |

| 10 | Bester, 2012 [44] | South Africa | ELM | Fish fingers | True | Food/nutrition | Product |

| 11 | Boenigk, 2013 [45] | Germany | Attribution theory | Lodging | True | Food/nutrition | 1%, 25% of price |

| 12 | Chang, 2011 [46] | Taiwan, China | ELM | Shampoo, toilet paper, compact disc, movie ticket, bottled water, yoghurt | Fictitious | Food/nutrition | 5%, 25% of price |

| 13 | Chang, 2012 (S1) [31] | Taiwan, China | Cognitive dissonance, affect theory | Shampoo, toilet paper, ice cream, movie ticket | Fictitious | Educational | 10% of price |

| 13 | Chang, 2012 (S2) [31] | Taiwan, China | Consistency theory | Smartphone | Fictitious | Health | 5% of price |

| 14 | Chang, 2008 [47] | Taiwan, China | ELM | Shampoo, toilet paper, printer, e-dictionary, compact disc, movie ticket, stereo system, DVD player | Fictitious | N/A | 5%, 25% of price |

| 15 | Chang, 2018 (S1) [48] | Taiwan, China | Accessibility-diagnosticity framework | MP3 | Fictitious | Health | 5% of price |

| 15 | Chang, 2018 (S2) [48] | Taiwan, China | N/A | Granola bar | Fictitious | Food/nutrition, educational | 5% of price |

| 16 | Chen, 2014 [49] | China | Information integration theory | Dry batteries | Fictitious | Environmental, educational | 1%, 5% of profits |

| 17 | Chen, 2016 (S5) [35] | China | N/A | Sunglasses, baby food and care, bank, tea | True | Educational | 5% of sales |

| 18 | Choi, 2017 [50] | USA | Signaling, cognitive dissonance theory | Mug | N/A | Humanitarian aid | 5% of profits |

| 19 | Choi, 2019 [51] | USA | Attribution, associative theory | Fast food | True | Humanitarian aid, health | N/A |

| 20 | Cui, 2003 [52] | USA | Attribution theory | Grocery | Fictitious | Humanitarian aid, health | 5% of sales |

| 21 | Das, 2016 (S1) [53] | USA | Consistency theory | Coffee, toothpaste | Fictitious | Health, food/nutrition | USD 0.60 per sale, a portion of price |

| 21 | Das, 2016 (S2) [53] | USA | Cognitive bias theory | Cookies | Fictitious | Food/nutrition | USD 1 per sale, a portion of price |

| 22 | Elving, 2013 [54] | Amsterdam, Netherlands | Attribution, legitimacy, associative, consistency theory | Toilet paper | Fictitious | Sanitation, food/nutrition | USD 0.30 per sale |

| 23 | Folse, 2014 (S1) [55] | USA | PKM | Frozen pizza | True | Educational | USD 10, product |

| 23 | Folse, 2014 (S2) [55] | USA | Distributive justice theory | Frozen pizza, notebook | Fictitious | Educational | USD 10, product |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S1) [56] | USA | Attribution theory | Shampoo | True | Health | USD 0.05, 0.2, 0.8, 3.2 per sale |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S2) [56] | USA | PKM | Shampoo | True | Health | USD 0.75, 2.25, 6.75 per sale |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S3) [56] | USA | Social exchange theory | Shampoo | True | Health | USD 1, 4 per sale |

| 25 | Grau, 2007 (S1) [57] | USA | Signaling theory | Lotion | Fictitious | Health | N/A |

| 25 | Grau, 2007 (S2) [57] | USA | Attribution, frame theory | Calcium supplements | True | Health | USD 0.50 per sale |

| 26 | Hagtvedt, 2016 (S2) [58] | USA | N/A | Watch | True | Food/nutrition, educational, health | N/A |

| 26 | Hagtvedt, 2016 (S3) [58] | USA | N/A | Jeans | Fictitious | Food/nutrition | N/A |

| 27 | Hajjat, 2003 [59] | Oman | ELM | Fruit drink | Fictitious | Humanitarian aid | 0.1%, 5% of sales |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S2a) [60] | USA | CLT | Toothpaste, ice cream | Fictitious | Educational | Product, equal cash per sale |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S2b) [60] | USA | CLT | Socks, sunglasses | Fictitious | Humanitarian aid | USD 12.99 per sale |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S3) [60] | USA | CLT | Shoes | True | N/A | Product, equal cash per sale |

| 29 | Hamlin, 2004 [61] | New Zealand | N/A | Milk | True | Health, animal | USD 0.05 per sale |

| 30 | He, 2016 (S1) [62] | UK | Social cognitive theory | Shower gel | True | Food/nutrition, sanitation, educational, environmental | 2% of price/sales |

| 30 | He, 2016 (S2) [62] | UK | Social cognitive theory | Shower gel, bottled water | True | Food/nutrition, sanitation, educational, environmental | 2% of price/sales |

| 31 | Howie, 2018 (S1) [63] | USA | Cognitive dissonance theory | Hair care | True | Environmental | N/A |

| 31 | Howie, 2018 (S2) [63] | USA | Neutralization theory | Hair care | True | Environmental | N/A |

| 32 | Huang, 2018 (S1) [64] | USA | Social exchange theory | Credit card | N/A | Environmental | 0.5%, 1%, 1.5% of sales/profits |

| 32 | Huang, 2018 (S2) [64] | USA | Symbolic interaction theory | Credit card | N/A | Environmental | 1% of sales/profits |

| 33 | Human, 2012 [65] | South Africa | Social exchange, equity theory | Glue stick | True | Educational | USD 0.2, 1 per sale |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S1) [66] | Australia | Attribution theory | Speakers | True | Cultural | USD 5 per sale |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S2) [66] | Australia | Associative theory | Shoes | True | Health | USD 5 per sale |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S3) [66] | Australia | Value theory | Shoes | True | Health | USD 5 per sale |

| 35 | Kerr, 2013 [67] | USA | Consistency theory | Chocolate | Fictitious | Food/nutrition, health, animal | USD 3 per sale, a portion of price |

| 36 | Kim, 2016 [32] | USA | Self-categorization theory | Restaurant | Fictitious | Food/nutrition, health | N/A |

| 37 | Kleber, 2016 (S1) [68] | Austria | N/A | Concert ticket, caviar, watch, notebook, transportation ticket, stove, refrigerator, game console | N/A | N/A | 15% of price |

| 37 | Kleber, 2016 (S2) [68] | Austria | N/A | Thermos, lamp, washing machine, refrigerator | N/A | Humanitarian aid | 7% of price |

| 38 | Koschate-Fischer, 2016 (S4) [69] | Germany | Temporal contiguity principle | Bottled water | True | Health | USD 0.05, 0.25, 0.40 per sale |

| 39 | Kull, 2016 (S3) [70] | USA | Cognitive dissonance theory | Lodging | True | N/A | A portion of price |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S1) [71] | USA | Perceptual fluency theory | Lemonade | True | Health | 5% of sales |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S2) [71] | USA | Perceptual fluency theory | Lemonade | True | Health | N/A |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S3) [71] | USA | Perceptual fluency theory | Lemonade | True | Health, food/nutrition | N/A |

| 41 | Lafferty, 2007 [72] | USA | Consistency theory | Shampoo | Fictitious | Animal | N/A |

| 42 | Lafferty, 2009 (S1) [73] | USA | Social identity theory | Shampoo | True | Health, animal | N/A |

| 42 | Lafferty, 2009 (S2) [73] | USA | Consistency theory | Shampoo | True | Animal | N/A |

| 43 | Lafferty, 2014 [18] | USA | Self-categorization theory | Cereal | True | Environmental, health, animal, humanitarian aid | Donation per sale until USD 250,000 |

| 44 | Lee, 2013 [74] | USA | Consistency, social identity theory | T-Shirt | Fictitious | Educational, health | USD 1 per sale |

| 45 | Lii, 2011 [75] | Taiwan, China | Social identity theory, SOR | Shoes | True | Humanitarian aid | USD 10 per sale |

| 46 | Lii, 2012 [76] | Taiwan, China | Social identity, SOR social exchange | Smartphone | True | Humanitarian aid | USD 16 per sale |

| 47 | Lii, 2013 [77] | Taiwan, China | Social exchange, affect theory, CLT | Watch | True | Health | USD 10 per sale |

| 48 | Manuel, 2014 [78] | USA | ELM, functional attitude theory | Bottled water | Fictitious | Environmental | USD 0.10 per sale |

| 49 | Melero, 2016 [79] | Spain | N/A | Milk, printer, chocolate, MP3 | True | Environmental, food/nutrition | 3% of price |

| 50 | Mendini, 2018 (S4) [80] | USA | Attribution theory, ELM, RFT | Audio | True | Educational, humanitarian aid | x% of price |

| 51 | Minton, 2016 (S2) [81] | USA | Cueing theory | Cookies | N/A | Health, environmental | A portion of sales |

| 51 | Minton, 2016 (S3) [81] | USA | Spreading activation theory | Cookies | N/A | Health, food/nutrition | A portion of sales |

| 52 | Mizerski, 2001 [82] | Australia | ELM, TPB | Alcohol | N/A | Health, educational, | A portion of price |

| 53 | Nelson, 2017 [83] | USA | Weak theory | Sunblock | True | Health | USD 0.10 per sale |

| 54 | Olsen, 2003 (S4) [84] | Canada | N/A | Printer | Fictitious | N/A | 1%, 10% of price/profits |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S1b) [85] | USA | N/A | Calculator | Fictitious | Health, educational | 5% of sales |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S2) [85] | USA | N/A | Calculator | Fictitious | Health, educational | 5% of sales |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S3) [85] | USA | N/A | Notebook | Fictitious | Environmental, educational | 5% of sales |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S4) [85] | USA | N/A | Shampoo | Fictitious | Environmental, educational | 5% of sales |

| 56 | Sabri, 2018 [86] | France | Negativity effect theory | Water filter pitchers, coffeemaker | Fictitious | Food/nutrition | USD 0.30, USD 6.75 per sale |

| 57 | Samu, 2009 (S2) [87] | India | Information integration theory | Baby food and care | True | N/A | 10% of price |

| 58 | Schindler, 2017 [88] | Germany | Attribution theory | Smartphone | True | Health | USD 23 per sale |

| 59 | Sony, 2015 [89] | Thailand | N/A | Printer paper | Fictitious | Environmental | N/A |

| 60 | Tangari, 2010 (S1) [90] | USA | CLT | Nutritional supplement | True | Health | 50% of price |

| 60 | Tangari, 2010 (S2) [90] | USA | Protection motivation theory | Nutritional supplement | N/A | Health | N/A |

| 61 | Tucker, 2012 [91] | USA | ELM | Toilet paper | True | Environmental | USD 0.05 per sale |

| 62 | Vaidyanathan, 2013 [92] | Poland | Consistency theory | Lotion | Fictitious | Environmental | USD 0.65, 1.30 per sale |

| 63 | Van Quaquebeke, 2017 [93] | Germany | N/A | Bottled water, parcel service | Fictitious | N/A | USD 0.05 per sale |

| 64 | Vilela, 2016 (S1) [94] | USA | Gender schema theory | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 64 | Vilela, 2016 (S2) [94] | USA | Gender schema theory | Cereal | True | Educational | USD 0.10 per sale |

| 65 | Wiebe, 2017 [95] | Canada | CLT | Grocery | N/A | Educational, health | USD 5 per sale |

| 66 | Yoo, 2018 (S1) [96] | Korea | CLT | Bottled water | Fictitious | Educational, health | 5%, 40% of price |

| 66 | Yoo, 2018 (S2) [96] | Korea | CLT | Coffee | Fictitious | Educational, health | 5%, 40% of price |

| 67 | Youn, 2018 [16] | USA | CLT | Printer, yoghurt | Fictitious | Environmental | A portion of sales |

| 68 | Zhang, 2019 [97] | USA | Self-presentation, power theory | Restaurant | N/A | Educational, health | N/A |

| No. | Lead Author, Year | Independent Variable(s) | Moderator(s) | Mediator(s) | Effect(s) on PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aghakhani, 2019 (S1) [36] | Termination of CRM | Fit (brand–cause) | N/A | Negative |

| 1 | Aghakhani, 2019 (S2) [36] | Termination of CRM decision motivation, decision source | Decision motivation, decision source | N/A | Mixed, mixed |

| 2 | Arora, 2007 (S1) [37] | Presence of CRM | N/A | N/A | Positive |

| 2 | Arora, 2007 (S2) [37] | Presence of CRM | Consumer participation effort, promotion payoff destination, brand awareness | N/A | Positive |

| 3 | Bae, 2016 [38] | CRM ad appeal | Cause involvement | Visual fixation duration, company credibility, attitude toward CRMP | Positive |

| 4 | Baghi, 2017 (S1) [39] | Presence of CRM | N/A | Guilt | Positive |

| 4 | Baghi, 2017 (S2) [39] | Product type, fit (product–cause) | Fit (cause–product) | Guilt | Mixed, mixed |

| 5 | Baghi, 2013a [40] | (for-/non-profit) Brand awareness | N/A | N/A | N.s., positive |

| 6 | Baghi, 2013b [41] | (for-/non-profit) Brand awareness | N/A | N/A | Positive, positive |

| 7 | Baghi, 2018 (S1) [19] | Brand prominence disparity | N/A | Product attitude | Positive |

| 7 | Baghi, 2018 (S2) [19] | Brand prominence disparity | Brand type ((non)luxury) | Product attitude | Mixed |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S1a) [42] | Company motivation | Performance trade off | N/A | Positive |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S1b) [42] | Company motivation | Price trade off | N/A | Positive |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S2a) [42] | Company motivation | Performance trade off | N/A | Mixed |

| 8 | Barone, 2000 (S2b) [42] | Company motivation | Price trade off | N/A | Mixed |

| 9 | Barone, 2007 (S2) [43] | Fit ((retailer) company–cause) | Affinity with cause | N/A | Positive |

| 9 | Barone, 2007 (S3) [43] | Fit ((retailer) company–cause), affinity with cause | Retailer motivation, affinity with cause | N/A | Mixed, positive |

| 10 | Bester, 2012 [44] | Cause involvement, message framing | N/A | N/A | Positive, n.s. |

| 11 | Boenigk, 2013 [45] | Presence of CRM, donation amount, product price | Product price | N/A | Positive, positive, mixed |

| 12 | Chang, 2011 [46] | CRM ad appeal, product type, | Product type, donation amount | N/A | Mixed. mixed |

| 13 | Chang, 2012 (S1) [31] | Brand prominence disparity | Product type | N/A | Mixed |

| 13 | Chang, 2012 (S2) [31] | Cause value framing | Product type, | N/A | Mixed |

| 14 | Chang, 2008 [47] | Product type, donation amount, donation framing, product price | Product price, donation framing | Guilt, pleasure, amount of thoughts | Positive 1, negative, mixed, negative |

| 15 | Chang, 2018 (S1) [48] | Donation type | Fit (product–cause) | N/A | Mixed |

| 15 | Chang, 2018 (S2) [48] | Donation type | Fit (product–cause), product type | N/A | Mixed |

| 16 | Chen, 2014 [49] | Corporate ability, CSR | Fit (company–cause) | Attitude toward company, product, CRMP | Positive |

| 17 | Chen, 2016 (S5) [35] | CSR type | Self-construal | N/A | Positive 2 |

| 18 | Choi, 2017 [50] | Status-seeking, guilt | Recognition | N/A | Mixed |

| 19 | Choi, 2019 [51] | Brand equity, Perceived fit, complementary fit (company–cause) | Brand equity | N/A | Mixed, mixed, mixed |

| 20 | Cui, 2003 [52] | Cause type, cause proximity, donation length/frequency, gender | N/A | N/A | Positive, n.s., positive, positive 3 |

| 21 | Das, 2016 (S1) [53] | Fit (product–cause), donation qualifier | Product type | N/A | Mixed, mixed |

| 21 | Das, 2016 (S2) [53] | Fit (product–cause), donation qualifier | Purchase type | N/A | Mixed |

| 22 | Elving, 2013 [54] | Fit (company–cause), reputation | Companies’ prior reputation | Skepticism | Positive, n.s. |

| 23 | Folse, 2014 (S1) [55] | Donation type | Consumer participation effort | Company motivation | Positive 4 |

| 23 | Folse, 2014 (S2) [55] | Donation type, fit (company–cause, product–cause) | N/A | Company motivation | Positive 4, positive, positive |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S1) [56] | Donation amount, purchase quantity requirement | N/A | Company motivation, perceived CSR | N.s., negative |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S2) [56] | Donation amount, purchase quantity requirement | Consumer participation effort | Company motivation, perceived CSR | Positive, negative |

| 24 | Folse, 2010 (S3) [56] | Donation amount, purchase quantity requirement | N/A | Company motivation, offer elaboration, perceived CSR, brand attitude | Positive, negative |

| 25 | Grau, 2007 (S1) [57] | Cause involvement, donation proximity | Cause involvement | N/A | Positive, mixed |

| 25 | Grau, 2007 (S2) [57] | Message framing | Cause involvement | Evaluation of CSR | N.s. |

| 26 | Hagtvedt, 2016 (S2) [58] | Brand type, the presence of CRM | N/A | Guilt | Positive 5, mixed |

| 26 | Hagtvedt, 2016 (S3) [58] | Store brand type | N/A | Guilt | Positive 5 |

| 27 | Hajjat, 2003 [59] | Type of marketing | Cause involvement, donation amount | N/A | Mixed |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S2a) [60] | Donation type, product type | Product type | N/A | N.s., mixed |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S2b) [60] | Donation type | Product type | Perceived helpfulness, perceived monetary value of the donation | N.s., n.s. |

| 28 | Hamby, 2016 (S3) [60] | Donation type | N/A | Perceived helpfulness, perceived personal role, imagery of the beneficiary | Negative 4 |

| 29 | Hamlin, 2004 [61] | Fit (product–cause) | N/A | N/A | Positive |

| 30 | He, 2016 (S1) [62] | Consumer moral identity centrality, brand social responsibility image, brand familiarity | Brand social responsibility image | N/A | Mixed, positive, positive |

| 30 | He, 2016 (S2) [62] | Consumer moral identity centrality, brand emotional attachment | Brand emotional attachment | N/A | Mixed, positive |

| 31 | Howie, 2018 (S1) [63] | Campaign effort | N/A | Perceived cause importance, CSR | Negative |

| 31 | Howie, 2018 (S2) [63] | Campaign effort | Choice of cause | Perceived cause importance, CSR | Mixed |

| 32 | Huang, 2018 (S1) [64] | Donation amount | N/A | N/A | Mixed |

| 32 | Huang, 2018 (S1) [64] | Donation framing | Individual’s propensity to volunteer, environmental concern | N/A | Mixed |

| 33 | Human, 2012 [65] | Donation amount, recipient’s familiarity and brand presence | N/A | N/A | N.s. |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S1) [66] | Celebrity social responsibility | N/A | Co-branding authenticity | Positive |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S2) [66] | Celebrity social responsibility | N/A | Co-branding authenticity, co-branding fit (celebrity-product) | Positive |

| 34 | Ilicic, 2019 (S3) [66] | Celebrity social responsibility | Consumer self-transcendence value | Co-branding authenticity | Positive |

| 35 | Kerr, 2013 [67] | Fit (product–cause), donation framing | Need for cognition | N/A | Mixed |

| 36 | Kim, 2016 [32] | Cause type, message type | N/A | N/A | N.s., positive 6 |

| 37 | Kleber, 2016 (S1) [68] | Donation framing, product type, product price | Consumer numerical ability | N/A | Mixed, negative 1, negative |

| 37 | Kleber, 2016 (S2) [68] | Donation framing, product price | Consumer numerical ability | N/A | Mixed, negative |

| 38 | Koschate-Fischer, 2016 [69] | Donation amount | Timing of the donation | Attributed company motives, perceived price fairness | Mixed |

| 39 | Kull, 2016 (S3) [70] | Presence of cause choice in CRM | Brand image | Empowerment, engagement | Mixed |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S1) [71] | Fit (product–cause) | N/A | Perceived company motives | Positive |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S2) [71] | Fit (product–cause) | N/A | Affective response toward charity | Positive |

| 40 | Kuo, 2015 (S3) [71] | Fit (company–cause) | Type of fit (company–cause) | Perceived company motives | Mixed |

| 41 | Lafferty, 2007 [72] | Fit (brand–cause), corporate credibility | Corporate credibility | N/A | N.s., positive |

| 42 | Lafferty, 2009 (S1) [73] | Cause importance, brand familiarity | Brand familiarity | N/A | Mixed, mixed |

| 42 | Lafferty, 2009 (S2) [73] | Fit (brand–cause), brand familiarity | Brand familiarity | N/A | N.s., n.s. |

| 43 | Lafferty, 2014 [18] | Cause category, cause cognizance | Brand familiarity, cause importance | N/A | N.s., positive |

| 44 | Lee, 2013 [74] | Fit (brand–cause) | Team identification; cause organizational identification | Attitude toward CRMP | Positive |

| 45 | Lii, 2011 [75] | CSR type | N/A | Consumer–company identification | Positive 3 |

| 46 | Lii, 2012 [76] | CSR type | CSR reputation | Consumer-company identification, brand attitude | Positive |

| 47 | Lii, 2013 [77] | CSR type | Brand social distance, cause spatial distance | Company credibility, brand attitude | Positive |

| 48 | Manuel, 2014 [78] | Functional fit (CRM message–consumer participation motive), consumer skepticism, perceived message quality | Consumer skepticism, perceived message quality | N/A | Mixed, negative, positive |

| 49 | Melero, 2016 [79] | Fit (product–cause), product type | N/A | N/A | N.s., negative |

| 50 | Mendini, 2018 [80] | Type of fit | N/A | Trust, skepticism | Positive 7 |

| 51 | Minton, 2016 (S2) [81] | Presence of CRM | N/A | N/A | Positive |

| 51 | Minton, 2016 (S3) [81] | Cause type, consumer health interest, nutrition knowledge | Consumer health interest, nutrition knowledge | N/A | N.s. |

| 52 | Mizerski, 2001 [82] | Type of CRM | N/A | N/A | N.s. |

| 53 | Nelson, 2017 [83] | The timing point before/after seeing the CRMP | Gender, brand usage | N/A | Mixed |

| 54 | Olsen, 2003 (S4) [84] | Donation amount, donation framing | N/A | N/A | Positive, positive 8 |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S1b) [85] | Choice of cause in CRM | N/A | N/A | Positive |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S2) [85] | Choice of cause in CRM | Collectivism | Perceived personal role | Mixed |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S3) [85] | Choice of cause in CRM | Perceptual fit (company–cause) | Perceived personal role | Mixed |

| 55 | Robinson, 2012 (S4) [85] | Choice of cause in CRM | Goal proximity | Perceived personal role | Mixed |

| 56 | Sabri, 2018 [86] | Type of CRM | N/A | Skepticism toward the altruistic and sincere motives | Mixed |

| 57 | Samu, 2009 (S2) [87] | Fit (brand–cause), (brand/cause) dominance | N/A | N/A | Positive, mixed |

| 58 | Schindler, 2017 [88] | Persuasion strategy | Communicator’s experience regarding social engagement | Perceived company motives | Mixed |

| 59 | Sony, 2015 [89] | Green strategy | N/A | N/A | Positive |

| 60 | Tangari, 2010 (S1) [90] | Temporal framing within the CRM ad | Consumers’ temporal orientation | N/A | Mixed |

| 60 | Tangari, 2010 (S2) [90] | Consumers’ temporal orientation | Temporal framing within the CRM ad, temporal framing of the societal need | Attitude toward CRMP | Mixed |

| 61 | Tucker, 2012 [91] | Ecological ad appeal | Individual environmental protection attitude, behavior, perceived consumer effectiveness | Ad involvement, ad credibility, attitude toward the ad, brand | N.s. |

| 62 | Vaidyanathan, 2013 [92] | Donation amount, donation source, commitment | N/A | Perceived value | Mixed, positive 9, positive |

| 63 | Van Quaquebeke, 2017 [93] | Presence of CRM | Ethical leadership | Self-congruence | N.s. |

| 64 | Vilela, 2016 (S1) [94] | Gender | N/A | N/A | Positive 3 |

| 64 | Vilela, 2016 (S2) [94] | Presence of CRM, gender | N/A | Elaboration thoughts | Mixed |

| 65 | Wiebe, 2017 [95] | Proximal framing of CRM appeal, | Perceived consumer effectiveness | N/A | Negative |

| 66 | Yoo, 2018 (S1) [96] | Donation amount | Construal level | Perceived benefits, perceived monetary sacrifice | Mixed |

| 66 | Yoo, 2018 (S2) [96] | Donation amount | Construal level; presence of emoticon | Perceived benefits, perceived monetary sacrifice | Mixed |

| 67 | Youn, 2018 [16] | Temporal duration | Self-construal, product involvement | Attributed company altruistic motives | Negative |

| 68 | Zhang, 2019 [97] | Type of CRM | Type of social power state, type of companion | N/A | Mixed |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, A.; Saleme, P.; Pang, B.; Durl, J.; Xu, Z. A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229609

Zhang A, Saleme P, Pang B, Durl J, Xu Z. A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229609

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Anran, Pamela Saleme, Bo Pang, James Durl, and Zhengliang Xu. 2020. "A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229609

APA StyleZhang, A., Saleme, P., Pang, B., Durl, J., & Xu, Z. (2020). A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies Investigating the Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability, 12(22), 9609. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229609