Abstract

Organizations rely heavily on audits and compliance related activities to prove their competency, credibility, and firm performance. Sustainability audits encompass entire supply chains and are very complex due to, firstly, the global nature of supply chains and, secondly, the expansive scope of sustainability, which may include financial, manufacturing, social, and environmental audits. Adding to this dilemma is the absence of a consensus on standards related to sustainability, resulting in differences, variations, and multiple interpretations. While the frequency, complexity, and scope of audits has increased, unfortunately so has the incident of audit fraud, which has seen increasing media coverage in recent times, often implicating major multinationals and their supply chains. We posit that this trend of increasing audit activity is causing “audit fatigue”, which, in turn, may influence the audit outcome, i.e., either audit fraud or a clean audit. This study proposes that audit fatigue is a genuine issue faced by organizations and needs to be conceptualized.

1. Introduction

Audits have become a regular feature in the day to day affairs of competitive organizations. Recent times have seen an increase in audit activity [1]. Whereas, in the past, audits were confined to one organization or sometimes just a single department within an organization. e.g., ISO 17025 lab certification, now entire supply chains are expected to be audited, including suppliers and distributors. Owing to the global nature of supply chains, this is not an easy task. This increase has been necessitated due to the changing nature of competition, which is no longer between individual businesses but rather between their supply chains [2]. In other words, it takes an entire supply chain’s coordinated and combined effort to produce and deliver a product and not just one organization. Hence, organizations put a lot of emphasis on having a well-oiled network of suppliers and distributors and rely on audits to ensure their entire value chain (value chain is defined as the steps/processes that add value to a product, starting from the raw material to its finished form; all members in a supply chain may not be adding value to the product) is up to the mark [3]. Consequently, the scope of audit has grown beyond the confines of a single organization to cover entire supply chains. All suppliers are expected to conform to stringent standards. This exercise is costly, time consuming, and never ending. The constant fear of bad publicity, financial losses, job insecurity, and lawsuits has become an everyday reality. If news of non-compliant suppliers breaks out in public, the financial implications can be disastrous [4,5,6].

This is not the only reason for an increase in audit activity. In the past, audits used to revolve around basic themes of accounting, product/process quality, or performance. This is no longer the case. Under the global quest for sustainability and tremendous from pressure of regulators, consumers, NGOs, and shareholders [7], this scope has grown [8] to encompass environmental impact (responsible sourcing, carbon footprint, energy usage, resource wastage, reuse, recycling, landfills, etc.) and social impact (working conditions, equal opportunity, child labor, corporate social responsibility (CSR), diversity, community involvement, etc.). These numerous factors cannot be covered in one audit; hence, the need for multiple audits has grown. This has also given rise to several initiatives/associations, such as Supplier Ethical Data Exchange (SEDEX), Fair Factory Clearinghouse (FFC), and Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI) [9,10,11], among others, aimed at the harmonization of standards and data sharing amongst members to avoid duplication of effort [12]. While such initiatives aim towards reducing the audit burden and have improved sustainability reporting, they have yet to gain traction [13]. Unfortunately, the expansive scope of sustainability is not the only problem surrounding this concept. Sustainability is widely understood through the lens of the triple bottom line [14]. However, each industry has its own interpretation of what it entails. Various explanations exist on how to measure, report, and incorporate it into the fabric of corporate culture. This has not only created multiple industry standards for sustainability but has also resulted in redundancy. A social accountability audit conducted to appease one client may not be covering the conditions of a second client, who may have a different set of needs. A supplier with several customers, each using their own preferred standard, might have to manage many differing, sometimes contradictory, requirements [15]. This lack of consistency puts tremendous administrative pressures on the auditee and diverts focus from other productive pursuits.

The problem lies at the confluence of the above factors of frequent audits, complex supply chains, and the variety of sustainability standards, giving rise to “audit fatigue” [16,17,18,19], generally understood as a phenomenon arising from the duplication of effort as a consequence of numerous audits and resulting in high costs and effort [9,20]. While the majority of organizations undergoing numerous audits may face this phenomenon, it has somehow eluded the probing attention of the research community. Whether and how audit fatigue influences the audit outcome is yet to be explored. It is proposed that, once audit fatigue sets in, it has the potential to distract the auditee from the true objective of the audit (self-improvement, transparency, and compliance) and forces them to view the entire process as a mundane and routine task that needs to be completed as quickly as possible, sometimes using wrongful claims, data, and documentation. This can be observed from the extraordinary rise in reported corporate fraud cases worldwide and increasing countermeasures in the form of institutionalized fraud prevention programs and whistle blower laws [21]. While audit fraud has been researched frequently, the role of audit fatigue in audit fraud has not been explored in general and especially not in the context of sustainability reporting. Audit fatigue becomes even more prevalent when supply chains and a variety of sustainability standards are at play. In this study, we explore the link between audit fatigue and audit outcome and posit that audit fatigue has the potential to render the audit result suspect and lacking in veracity.

This study presents a novel conceptual framework, adds to the literature examining the concept of audit fatigue in a new light, and proposes a causal relationship between audit frequency and audit outcomes via audit fatigue. Hence, this concept falls in the revising (“Revising is to see something that has been identified in a new way; to reconfigure, shift perspectives, or change.”) and delineating (“Delineating is to detail, chart, describe, or depict an entity and its relationship to other entities.”) categories of conceptual models identified by MacInnis [22]. It falls in the revising category because we are seeing audit fatigue in a new perspective. It falls in the delineating category because audit fatigue’s effect on audit outcome is proposed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper exploring audit fatigue and the relationship to audit outcomes, especially in the context of sustainable supply chains, and it opens up new areas for further research in this domain. Scholars can further study this phenomenon and assist practitioners in timely identification, measurement, and eventual eradication of the ill effects, if any, of audit fatigue. Furthermore, effective management of audit fatigue will assist practitioners and stakeholders in ensuring the reliability of an audit outcome, which will help in achieving true sustainability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Fog of Sustainability

The concept of sustainability was proposed in the United Nations Bruntland Report in 1987 and can be broadly summarized as the ability to meet our own needs in a way that does not incapacitate future generations from meeting their needs [23]. Generally, this concept is composed of three pillars: economic, environmental, and social, also known informally as profits, planet, and people or the “triple bottom line” [24]. Sustainability is the latest buzzword [25], often promoted as the ethical choice for the discerning consumer, even though there are many diverging point of views and debates over what sustainability truly means [26]. Where one school of thought believes in according equal importance to these three dimensions, another prioritizes financial justifications, asking “how supply chains can benefit from addressing social and environmental practices” [27], thus making environment and society subservient to economic interests. Another opinion takes a totally opposing view, also called the ecological/environment dominant view, asking “how can a supply chain be truly sustainable?” [28,29,30]. This is a more idealistic approach in which the environment comes first, society comes second, and economic interests come last. These varying opinions speak volumes about the different approaches taken by practitioners and academics. Several studies confuse sustainability with corporate social responsibility (CSR), reducing environmental harm [31], or achieving several certifications [32]. This has resulted in the creation of many standards revolving around sustainability [33,34,35], each having their own interpretation of what sustainability entails.

The foggy concept of sustainability has been misused, much to the advantage of corporations, with some marketers taking full advantage of the widely acknowledged ambiguities implicit in the term [36]. These unscrupulous elements have hijacked the agenda for sustainability by using fraudulent marketing gimmicks to misguide the consumer and other stakeholders. Green labelling, green washing, and eco labeling are some of its manifestations [37,38]. While we wait for the answer to the question of what is to be measured, the question of how is also becoming a cause of confusion.

The lack of consensus on the definition has also resulted in a multitude of evaluation approaches such as Balance Scorecard [39,40], Life Cycle Assessment [41,42], Fuzzy set approaches [43,44], Data Envelopment analysis [45,46], and Analytical Hierarchy/Network Process [47,48]. These approaches lack objectivity because they can measure only those phenomena with features that can be quantified, controlled, and observed directly with the instruments at hand [49,50]. Organizations tend to cherry pick those approaches that prove their sustainability credentials. This confusion has resulted in a potpourri of standards, approaches, and interpretations being adopted by organizations and regulators. It can be safely stated that sustainability is a “wicked problem” [51,52,53] with no clear definition, no right or wrong solution but rather better or worse ones, each stakeholder having a widely different frame of reference for the problem, constraints and resources for the solution changing over time, and the problem remaining unresolved. Multiple audits become a necessary tool to bring some semblance of objectivity and sense to this complex situation. Interestingly, there is scant research on the effects of vague and numerous sustainability standards on audit outcome [54].

2.2. Complex Supply Chains

The modern consumer is very conscious when it comes to: (1) what products they consume, (2) how they were made, (3) where were they sourced, and (4) how the product will be disposed of [55]. Sustainability cannot be achieved without a sustainable supply chain [56], so the onus of achieving this goal falls on the entire supply chain. Consumer groups, NGOs, and regulators keep an increasingly sharp eye on industry practices and demand compliance. This has put organizations, along with their supply chains, under the spotlight [7,57]. A typical manufacturer, who interacts only with their first tier supplier and is hardly aware of their second tier suppliers [58,59], finds it difficult to ensure compliance throughout their supply chain. Adding to this is the fact that organizations with diverse product lines usually have multiple supply chains, each serving a different product category [60]. Supply chain complexity has seen its fair share of research [61,62,63,64], but scholars have not paid due attention on the impact it may have on audit outcome.

2.3. The Rise of the Audit Culture—Frequency, Variety and Outcomes

Stakeholders are increasingly relying on third party audits to ensure impartiality, transparency, and compliance [65,66]. The demand for audits has grown overtime to cover a variety of topics, including financial, accounting, stores and inventory, energy use, environmental impact, personal safety, worker rights, workforce diversity, organic chemicals, food, products, sustainable development, supply chains, etc. What Powers [1,67,68] calls the audit society and an audit explosion is actually a manifestation of supply chain complexity and the ever increasing pressure of society on producers to be sustainable. However, rising evidence suggests that this audit explosion has not lived up to expectations. Sustainability auditing has been criticized for enabling big corporations to “greenwash” their products [69], misuse information complexity [70], mislabel [71], under report [72], and sometimes even mislead the general public [73]. The use of audit as a means to control and pressurize suppliers during negotiations has also been reported [74]. The culture of concealment in corporations and their clout over regulators [75] allows them to get their way, regardless of the ethical and legal implications, sometimes to the detriment of human life. The ever increasing cases of misleading sustainability claims are now getting noticed [76]. This has given rise to a new term, “sustainability fraud” [54].

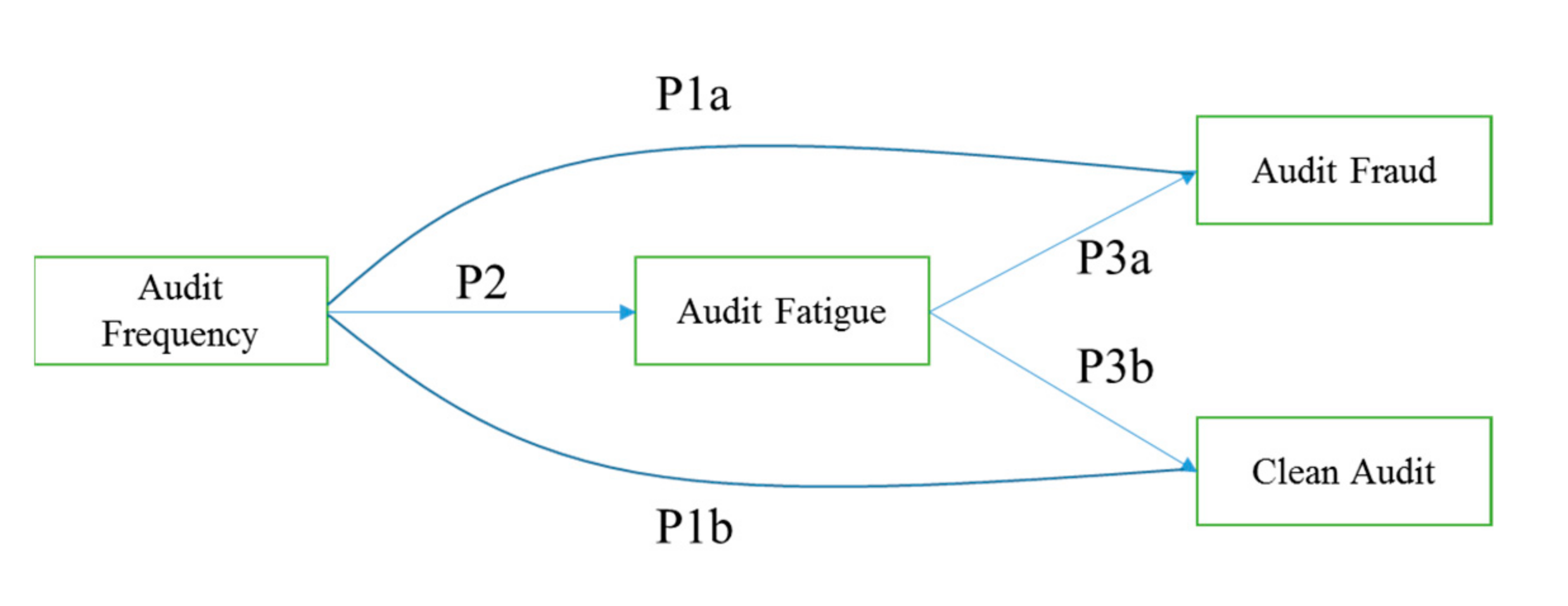

According to Zahra et al. [77], fraud is defined as “deliberate actions taken by management at any level to deceive, con, swindle or cheat investors or other key stakeholder”. Fraud has been a widely studied subject in theory and practice [78,79], albeit with more focus on financial and accounting aspects. In spite of audits becoming acceptable and popular among governments and regulators, the audit regime continues to protect the interests of the industry; hence its neutrality, objectivity, and legitimacy is being challenged [16]. The recent high profile scandals, including the Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal [80,81,82], the Boeing 737 Max crash [83], now common automotive recalls [84], increasing reports of greenwashing [85], and misuse of the sustainability index [86], are a telltale sign that something is amiss. This leads us to the following proposition (as shown in in Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for audit fatigue.

Proposition 1a: The increase in audit frequency leads to an increase in audit fraud.

In order to have a balanced view, there is also a need to examine the positive aspects of frequent audits. Competitive organizations have converted the increasing demand for frequent and multiple audits into an opportunity to improve their processes [87,88]. This has enabled firms to focus on knowledge management and to become learning organizations. They have hired dedicated internal audit teams and have employed best practices [89]. In order to have a “clean audit”, also called a high quality audit, which gives a true picture and is free from misstatements [90], organizations focus on organized, detailed, and formal documentation practices to ensure that the audit process is smooth, quick, and result oriented. This is a requirement of global brands (e.g., Nike, Adidas, Levi’s, etc.) for their suppliers. Proper and thorough documentation is crucial for fulfilling the requirements of numerous audits and international standards and certifications. If the suppliers do not meet these requirements, they risk losing their clients. Due to the high financial stakes, such audits are taken seriously and act as a stepping stone towards improved firm performance [87,91,92]. In order to have reliable documentation throughout their networks, organizations invest in their supply chains’ capacity building [93]. Studies also suggest that, under certain conditions, audits have a positive, albeit uneven, impact on the performance of supply chains [94,95,96]. This leads us to present the following proposition:

Proposition 1b: The increase in audit frequency leads to clean audits.

2.4. Audit Fatigue: Tying All Elements Together

Merriam Webster defines fatigue as “a state or attitude of indifference or apathy brought on by overexposure to repetitive task” [97]. Potential causes are task repetition, monotony, eating habits, lifestyle, medication, prolonged stress, and lack of physical exercise and sleep [98]. It would be prudent to clarify that this research is discussing neither stress nor fatigue, which are often mentioned together, especially in the clinical domain (sports, physical, mental work, etc.). Neither are we discussing audit related stress, which has been researched mostly from the perspective of the auditors [99]. Audit fatigue differs from simple fatigue as it is a direct consequence of overexposure to multiple and frequent audit activity and not due to the typical causes mentioned above. Several industry reports and whitepapers have mentioned this term as the phenomenon induced by frequent audits from numerous clients [18,100]. Some scholars have made a fleeting reference to audit fatigue as an outcome of multiple audits [19,20,101,102] but have stopped short of exploring audit fatigue beyond the basic definition or studying its antecedents and effects. Almost all of these scholars were mainly focused on other aspects of audit activity, such as sustainability initiatives/associations and supplier audit standards, e.g., BSCI, SEDEX, FFC [9,10], sustainability assessment schemes [10,19], ethical audit regimes [16], information asymmetries in multi-tier supply chains [103], etc. Their main focus was on reducing audit fatigue through various approaches rather than on explaining what audit fatigue is in itself or the dynamics (environment/context, causes, and consequences) surrounding this concept. Audits of complex supply chains and sustainability practices, often involving numerous suppliers spread over several countries and covering wide social and environmental aspects, further add to audit fatigue. While the link between audit frequency and audit fatigue is implicitly suggested, the need for further empirical inquiry exists. From the above literature, the following proposition can be drawn:

Proposition 2: The increase in audit frequency leads to audit fatigue.

This brings us to the question of whether audit fatigue has any impact on the audit outcome, which can go either towards audit fraud or a clean audit. As audits become more frequent, the pressure on top management and, subsequently, on the lower staff grows, and so does the likelihood of the auditee using questionable means to fulfil the audit requirements [104]. There is an implicit expectation for the auditee to provide necessary support to the auditor, which is usually not their primary job, and, as such, there is no associated incentive. In the absence of an explicit reward, these audits are not considered a welcome activity by them [105,106]. The indifference and apathy resulting from multiple audits can result in the auditee taking the audit activity lightly and cut corners during documentation, sometimes using fraudulent data and claims [107]. Various organizations in a supply chain may have differing procedures and documentation approaches [108]. This disharmony can result in additional effort on the part of the audit team to align, reformat, clean, and record the data spread amongst various partner firms [107], thus raising the chances of error and/or fraud. Various sustainability reporting standards, including Global Reporting initiative (GRI), and numerous sustainability indices are now facing criticism for being misused to camouflage problems under the guise of sustainability reporting [61,109,110]. This leads us to propose the following proposition:

Proposition 3a: Audit fatigue may lead to audit fraud.

The alternate outcome to audit fatigue is a clean audit, which fulfills all objectives and is devoid of any misrepresentation. Research has shown that employing multiple third party audit firms and their regular rotation improves audit outcomes [92], thus supporting the argument that audit fatigue may not always be bad. Other factors, such as an organization’s culture and leadership style, also play a very vital role in handling the various pressures [111,112] that may arise from audit fatigue. Similarly, individuals with more audit experience and effective learning environments result in better handling of audits [113]. These factors lead us to the following proposition:

Proposition 3b: Audit fatigue may lead to a clean audit.

The model (Figure 1) being proposed here addresses how audit frequency may affect audit fatigue and, subsequently, audit outcome.

Nowadays, audits have gained a central position in determining the sustainability practices of supply chains. There is need to consider the link between frequent audits and audit fatigue and the subsequent impact on audit outcomes. We urge researchers to explore additional factors that may influence audit frequency; for instance, regulatory pressures, consumer awakening, and social dimensions. This can be further explored and investigated through empirical research using qualitative and quantitative approaches. Academics need to answer several questions, including but not limited to the following research questions. Whether these factors (complex supply chain, sustainability standards, and types of audits) are the only ones causing multiple audits? How to operationalize the construct for audit fatigue? Can a simple metric be used for audit fatigue to ascertain the vulnerability of a sustainability audit report? What are the antecedents of audit fatigue? What are the manifestations of audit fatigue apart from audit fraud? Is audit fatigue a universal phenomenon or just native to sustainability audits? Is audit fatigue affected by cultural difference between collectivist and individualistic societies? Does the employee’s attitude play any role in handling audit fatigue? Researchers also need to study the effects of audit fatigue on other fields, including the financial sector, organic agribusiness, aquaculture, manufacturing, the development sector, the public sector, education, hospitals, and pharmaceuticals, which have seen an exponential rise in audit related activities.

3. Conclusions

The simplicity in the term audit fatigue has conveniently concealed its impact on audit outcome. Society’s increasing dependency on audit for all sorts of decisions is based on the premise that audits are objective, transparent, independent, and generalizable. Increasing reports of audit fraud are challenging this trust. If audit fatigue has any impact on audit outcome, as proposed in this paper, this phenomenon gains significant importance for today’s society. It is a long way before the perfect audit report in all senses is achieved. Until then, cases of misrepresentation and misleading sustainability claims by organizations will continue. Audit fatigue is a reality for the industry, and understanding relevant antecedents and consequences and finding countermeasures has the potential to contribute to reducing such incidents. This can contribute to improving trust in the audit report. This study has laid the foundation for further research by proposing a conceptual framework for audit fatigue, in which audit frequency plays the role of a predictor of audit outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.K., M.H.A., and M.N.A.; original draft preparation, M.K.K. and S.T.H.S.; review and editing, M.K.K., M.H.A., M.N.A., and S.T.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable and constructive suggestions, which greatly improved our revised manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Power, M. Modelling the microfoundations of the audit society: Organizations and the logic of the audit trail. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management| Martin Christopher; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Aydin, G.; Parker, R.P. Social Responsibility Auditing in Supply Chain Networks; Kelley School of Business Research Paper; Kelley School of Business: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Business-Insider. Nikola founder Trevor Milton Resigned from the Company’s Board Following Fraud Allegations. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/nikola-founder-trevor-milton-resigns-following-fraud-allegations-2020-9 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- The-NewYork-Times. Theranos Is Shutting Down. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/05/health/theranos-shutting-down.html (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Washington-Post. Solyndra Solar Company Fails After Getting Federal Loan Guarantees. Available online: Washingtonpost.com/politics/solyndra-solar-company-fails-after-getting-controversial-federal-loan-guarantees/2011/08/31/gIQAB8IRsJ_story.html (accessed on 10 September, 2020).

- Hassini, E.; Surti, C.; Searcy, C. A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castka, P.; Searcy, C.; Mohr, J. Technology-enhanced auditing: Improving veracity and timeliness in social and environmental audits of supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.C. Private regulatory capture via harmonization: An analysis of global retailer regulatory intermediaries. Regul. Gov. 2019, 13, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, I.J.; Schwarzkopf, J.; Müller, M. Exploring Supplier Sustainability Audit Standards: Potential for and Barriers to Standardization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzau, L. The Business Social Compliance Initiative. A system for the continuous improvement of social compliance in global supply chains. Zfwu Z. Für Wirtsch. Und Unternehm. 2011, 12, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, O.J. Guidelines for the integration of certifiable management systems in industrial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn Murphy, C.; Cia, C. Supply chain complexity awaits technology solutions. Strategy Financ. 2014, 96, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Miemczyk, J.; Luzzini, D. Achieving triple bottom line sustainability in supply chains. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2019, 39, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Klassen, R.; Johnston, D.; Shevchenko, A.; Sharma, S. Are safety and operational effectiveness contradictory requirements: The roles of routines and relational coordination. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, G.; Lister, J.; Dauvergne, P. Governing global supply chain sustainability through the ethical audit regime. Globalizations 2017, 14, 958–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S. Supply Chain Briefing Part 2: Working with Competitors—Cooperation Conundrums. Available online: https://www.reutersevents.com/sustainability/print/36379?utm_source (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Rammohan, S. Toward a More Responsible Supply Chain: The HP Story. Supply Chain Manag. Rev. 2009, 8, 35. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, J. Sustainability Assessment: A Pathway for Reducing Audit Fatigue? International Institute of Industrial Environmental Economics; Working Paper; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L.; McGrath, P.; Harrigan, F. What’s your strategy for supply chain disclosure? Mit Sloan Manag. Rev. 2016, 57, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, C. How corrupt are universities? audit culture, fraud prevention, and the Big Four accountancy firms. Curr. Anthropol. 2018, 59, S92–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAlfy, A.; Darwish, K.M.; Weber, O. Corporations and sustainable development goals communication on social media: Corporate social responsibility or just another buzzword? Sustain. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D.; Steffen, W.; Rose, D.B.; Daniell, K.; Felton, A.; Garnett, S.; Gilna, B.; Heinsohn, R.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Mind the sustainability gap. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Bansal, P. Instrumental and integrative logics in business sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montabon, F.; Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Making sustainability sustainable. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. Environment dominant logic: Concerning for achieving the sustainability marketing. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markman, G.D.; Krause, D. Theory building surrounding sustainable supply chain management: Assessing what we know, exploring where to go. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, L. The Standardization of Down-Streamed Small Business Social Responsibility (SBSR): SMEs and Their Sustainability Reporting Practices. In Social Entrepreneurship: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 670–685. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, L. Climate Change: How Debates over Standards Shape the Biophysical, Social, Political and Economic Climate. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2011, 18, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, F.C. Toppling the tripod: Sustainable development, constructive ambiguity, and the environmental challenge. Consilience 2011, 5, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C.; Hildebrandt, T.; Bailis, R. International sustainability standards and certification. In Sustainable Development of Biofuels in Latin America and the Caribbean; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 27–69. [Google Scholar]

- Espiner, S.; Orchiston, C.; Higham, J. Resilience and sustainability: A complementary relationship? Towards a practical conceptual model for the sustainability–resilience nexus in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castka, P.; Corbett, C.J. Governance of eco-labels: Expert opinion and media coverage. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, S.; Botero, C. Are eco-labels sustainable? Beach certification schemes in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1550–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.; Cruz-Machado, V. Investigating lean and green supply chain linkages through a balanced scorecard framework. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2015, 10, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanki, S.; Thakkar, J. A quantitative framework for lean and green assessment of supply chain performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Massa, I. Modeling social life cycle assessment framework for the Italian wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-W.; Hsu, C.-W.; Hu, A.H. An analytical framework for social life cycle impact assessment—Part 2: Case study of labor impacts in an IC packaging company. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaghi, M.; Mascle, C.; Baptiste, P.; Rostamzadeh, R. Sustainability assessment using fuzzy-inference technique (SAFT): A methodology toward green products. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 56, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygun, Ö.; Dede, A. Performance evaluation of green supply chain management using integrated fuzzy multi-criteria decision making techniques. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016, 102, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhedayatian, S.M.; Azadi, M.; Saen, R.F. A novel network data envelopment analysis model for evaluating green supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajbakhsh, A.; Hassini, E. A data envelopment analysis approach to evaluate sustainability in supply chain networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Singh, R.K.; Murtaza, Q. Triple bottom line performance evaluation of reverse logistics. Compet. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Çifçi, G. Evaluation of the green supply chain management practices: A fuzzy ANP approach. Prod. Plan. Control 2012, 23, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.; Rout, M. Can sustainability auditing be indigenized? Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S. A review of modeling approaches for sustainable supply chain management. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, J. Dialogue Mapping. In Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H. Transformational supply chains and the’wicked problem’of sustainability: Aligning knowledge, innovation, entrepreneurship, and leadership. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2009, 9, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmeier, M. Fraud in sustainability departments? An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckel, S. The sustainability society: A sociological perspective. Cult. Pract. Eur. 2017, 2, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.E.; Figueiredo, M.D. Practicing sustainability for responsible business in supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Sustainability measurement system: A reference model proposal. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Gold, S. Sustainability management beyond corporate boundaries: From stakeholders to performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M.; Knemeyer, A.M. Exploring the integration of sustainability and supply chain management. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics & Supply Chain Management; Pearson UK: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, C.; Wagner, S.M. Structural drivers of upstream supply chain complexity and the frequency of supply chain disruptions. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 36, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, S.; Grotenhuis, R.; van Goor, A.R. Assessing complexity of supply chains: Evidence from wholesalers. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Aitken, J.; Bozarth, C. A framework for understanding managerial responses to supply chain complexity. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. An Exploratory Investigation of the Effects of Supply Chain Complexity Performance. IIIE Trans. 2002, 49, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, K.; Haider, M.B.; Kokubu, K. Are third-party assurances preferable to third-party comments for promoting financial accountability in environmental reporting? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, V.S.; Osmundsen, T.C. Virtually the reality: Negotiating the distance between standards and local realities when certifying sustainable aquaculture. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M. The audit society—Second thoughts. Int. J. Audit. 2000, 4, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M. Research Evaluation in the Audit Society. In Wissenschaft unter Beobachtung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.K. Corporate social responsibility/sustainability reporting among the fortune global 250: Greenwashing or green supply chain. In Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Y.-S.; Cheng, Y.-C. The impact of information complexity on audit failures from corporate fraud: Individual auditor level analysis. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, S.; Cawthorn, D.M.; Hanner, R. Mislabeling seafood does not promote sustainability: A comment on Stawitz et al.(2016). Conserv. Lett. 2017, 10, 781–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Rovenpor, J.L.; Demir, M. Enhancing the quality of reporting in Corporate Social Responsibility guidance documents: The roles of ISO 26000, Global Reporting Initiative and CSR-Sustainability Monitor. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2017, 122, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Conversation. Spruiking the Stars: Some Home Builders Are Misleading Consumers about Energy Ratings. Available online: https://theconversation.com/spruiking-the-stars-some-home-builders-are-misleading-consumers-about-energy-ratings-136402 (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Busch, L. Governance in the age of global markets: Challenges, limits, and consequences. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Boeing’s ‘Culture of Concealment’ to Blame for 737 Crashes. Available online: Bbc.com/news/business-54174223 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- KPMG. The Rising Challenge of Sustainability Fraud; KPMG: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; Priem, R.L.; Rasheed, A.A. The antecedents and consequences of top management fraud. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorminey, J.; Fleming, A.S.; Kranacher, M.-J.; Riley, R.A. , Jr,The evolution of fraud theory. Issues Account. Educ. 2012, 27, 555–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Dacin, T.; Palmer, D. Fraud in accounting, organizations and society: Extending the boundaries of research. Account. Organ. Soc. 2013, 38, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mačaitytė, I.; Virbašiūtė, G. Volkswagen emission scandal and corporate social responsibility—A case study. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 2018, 2, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, M. How does greenwashing effect the firm, the industry and the society-The case of the VW emission scandal. Proc. FIKUSZ 2016 Symp. Young Res. 2016, 2016, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, N. A case study of Volkswagen unethical practice in diesel emission test. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Appl. 2016, 5, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pixley, J. Grounding the Robber Barons; Global Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nassar, S.; Kandil, T.; Kara, M.E.; Ghadge, A. Automotive recall risk: Impact of buyer‒supplier relationship on supply chain social sustainability. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los Angeles Times. Skepticism Grows over Products Touted as Eco-Friendly. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/business/la-xpm-2011-may-21-la-fi-greenwash-20110521-story.html#:~:text=To%20Marina%20Meadows%2C%20green%20may%20be%20the%20new%20white.&text=But%20environmentalists%20and%20some%20consumers,a%20practice%20they%20call%20greenwashing (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Lyytimäki, J.; Tapio, P.; Varho, V.; Söderman, T. The use, non-use and misuse of indicators in sustainability assessment and communication. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, U.; Javeed, S.A.; Latief, R. How Audit Quality Affects the Firm Performance with the Moderating Role of the Product Market Competition: Empirical Evidence from Pakistani Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, D.; Lawton, A.; Luo, B.N. Customer orientation and firm performance: The joint moderating effects of ethical leadership and competitive intensity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endaya, K.A.; Hanefah, M.M. Internal auditor characteristics, internal audit effectiveness, and moderating effect of senior management. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggelen, J. Global trends in audit quality, supervision, and standard setting. Maandbl. Voor Account. En Bedrijfsecon. 2018, 92, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwuigbe, U.; Teddy, O.; Uwuigbe, O.R.; Emmanuel, O.; Asiriuwa, O.; Eyitomi, G.A.; Taiwo, O.S. Sustainability reporting and firm performance: A bi-directional approach. Acad. Strategy Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- El-Dyasty, M.M. Multiple Audit Mechanism and Audit Quality: An Empirical Investigation. SSRN 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Pawar, K.S.; Bhardwaj, S. Improving supply chain social responsibility through supplier development. Prod. Plan. Control 2017, 28, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Regini, M.; Sabel, C.F. On Richard M. Locke, the promise and limits of private power: Promoting labor standards in a global economy, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2013. Sociol. Econ. Rev. 2014, 12, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M. The Promise and Limits of Private Power: Promoting Labor Standards in A Global Economy; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, R.M.; Qin, F.; Brause, A. Does monitoring improve labor standards? Lessons from Nike. Ilr Rev. 2007, 61, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster. Available online: Merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fatigue (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Crandall, R.; Perrewe, P.L. Occupational Stress: A Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suhardianto, N.; Leung, S.C. Workload stress and conservatism: An audit perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1789423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Fighting Fraud: A Never-Ending Battle; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, K.S. Third-Party Audit Programs for the Fresh-Produce Industry. In Microbial Safety of Fresh Produce; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; p. 321. [Google Scholar]

- Benstead, A.V.; Hendry, L.C.; Stevenson, M. Detecting and remediating modern slavery in supply chains: A targeted audit approach. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannibal, C.; Kauppi, K. Third party social sustainability assessment: Is it a multi-tier supply chain solution? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 217, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.C.; DeZoort, F.T.; Hermanson, D.R. Review of recent literature on pressure on CFOs to manipulate financial reports. J. Forensic Inverstigative Account. 2017, 9, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, P.R.; Crabtree, R.M.; Kerr, A.K. The Australian sport management job market: An advertisement audit of employer need. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, W.S. Perception of Auditors and Auditee on Public Sector Performance Audits. Policy Gov. Rev. 2019, 3, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Sitorus, S.M.; Surya, R.L.; Shauki, E.R.; Diyanti, V. Pressure, dysfunctional behavior, fraud detection and role of information technology in the audit process. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debicki, T.; Kolinski, A. Influence of EDI Approach for Complexity of Information Flow in Global Supply Chains; Business Logistics in Modern Management: Osijek, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Serdarasan, S. A review of supply chain complexity drivers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2013, 66, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Seele, P. Uncommitted deliberation? Discussing regulatory gaps by comparing GRI 3.1 to GRI 4.0 in a political CSR perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Mas, L.O.; Barac, K. The influence of the chief audit executive’s leadership style on factors related to internal audit effectiveness. Manag. Audit. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Hameed, W.; Mohammad, H.; Shahar, H.; Aljumah, A.; Azizan, S. The effect of integration between audit and leadership on supply chain performance: Evidence from UK based supply chain companies. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2019, 7, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-C.; Su, J.-M.; Tsai, S.-B.; Lu, T.-L.; Dong, W. A comprehensive survey of government auditors’ self-efficacy and professional Development for improving audit quality. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).