Abstract

Benefit Corporations (BCs) were introduced in Italy by Law 28-12-2015 N. 208 based on the previous experience of the USA. BCs are hybrid organizations with a blended economic and social/environmental purpose and aim to generate a positive impact on employees, environment, communities, and other stakeholders in addition to profit-making. For BCs, accountability is crucial to achieve social legitimacy and to prove their positive impact on society. Italian BCs are obliged to prepare and publish a yearly impact report. The present research aimed to explore the impact reporting practices of Italian BCs and to evaluate the quality of the published reports. 47 impact reports were collected from 192 websites, and a qualitative content analysis was performed on these reports. Furthermore, an evaluation instrument was built to measure impact reporting quality and to understand which determinants affected the reporting quality. The study allowed understanding that impact reporting practice was at a very early stage of evolution. Furthermore, the analysis focused on the importance of an external standard for promoting reporting quality. The findings of the study contributed to the existing literature on BCs and on reporting quality and allowed some practical implications for managers, policymakers, and standard setters.

1. Introduction

During the last decades, the attention to the relationship between business and society became crucial for the social legitimacy of firms and also for their development. The awareness of the role played by business to enhance social and environmental—as well as economic—sustainability is testified by the enlargement of the debate about the purpose of firms that engaged both scholars and practitioners [1,2,3,4,5]. The possible contribution of firms to sustainable development was, for example, at the very center of the statement of Business Roundtable in August 2019 about the company purpose [6] and the attention to sustainable development goals (SDGs) increased in all sectors of society, including business [7,8,9]. This movement regards traditional companies [10] and new hybrid forms of business that systematically combine economic objectives with different social or environmental goals in a blended purpose [11,12]. Haigh and Hoffman defined hybrid organizations as «organizations that combine elements of for-profit and nonprofit domains, maintaining a mixture of market- and mission-oriented practices, beliefs, and rationale» [13]. Other studies focused on the transformative role played by hybrid organizations in societal [14] or business context [15].

Nonetheless, the study fields about hybrid organizations are still open, and several aspects of their management and accounting have to be explored from a different perspective. One of the main topics faced by hybrid organizations concerns the legal and taxation structure that they can adopt [16]. Increasing attention was given to the formal architecture that organizations with blended goals can choose to develop their purpose better and achieve their goals. To answer this matter, some countries—first several states of USA, first of all, Maryland in 2010, and then Italy starting from 2016—adopted specific laws to discipline the legal form of benefit corporation (BC). BCs are for-profit firms that adopted a mixed purpose by including social or environmental goals in their statutory objective. Nonetheless, while BCs present themselves to customers, suppliers, public opinion, and all the stakeholders as purpose-driven organizations that combine economic and social goals, they have to be accountable to ensure the effectiveness of their social impact and promote legitimacy among their stakeholders. To build a trustworthy environment, BCs must reinforce their reputation by offering concrete instruments useful to evaluate their capability to create social impact.

Also, Italian Law witnesses the importance of accountability for BCs. Indeed, clause n. 382 of article 1 of Law 28-12-2015 n. 208 imposes to all Italian BCs to produce a yearly report that has to be attached to annual financial statements. This report has to show the benefit goals pursued by the firm, the impact evaluation, and the new goals that the firm intends to achieve during the following year. The importance of transparency is reinforced by the legal consequences established if a BC does not effectively pursue benefit goals. Indeed, clause n. 381 of the abovementioned norm compares this behavior to misleading advertisements and imposes the same legal treatment.

Accountability is crucial to create a trusty environment for the development of single BC and the BCs movement; consequently, impact reports are not only formal compliance but a strategic factor for BCs. Therefore, impact reporting quality has become an unavoidable factor for the effectiveness of accountability and the success of BCs.

The present research aims to explore the fields of impact reporting practice of Italian BCs to understand if and how they are accountable and if they concretely contribute to improving the transparency of markets by publishing data about their capacity in creating social impact. In detail, the study aims to answer the following research questions: (1) Do Italian BCs produce impact reports and publish them on their website? (2) Which are the main characteristics of impact reports published by Italian BCs? (3) Which are the main determinants that affect the quality of impact reports?

To answer to these research questions, the study focused on 192 websites of Italian BCs on which content analysis was performed to highlight characteristics of impact reporting practices of Italian BCs. Successively, an evaluation scale was build based on the normative requirement of reports and previous literature, and it was applied to the 47 impact reports. Data that emerged from the content analysis was analyzed by applying appropriate statistical methods to emerge the determinants of impact reporting quality.

Despite the increasing attention devoted to BCs, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have still attempted to examine impact reporting practice and the quality of impact reports. Therefore, the present research aims to explore and map the territory and contribute to the literature on BCs and, more generally, on reporting quality. Given that Italy was the first European country that introduced a law about BCs, but other European countries approached this new form of business, the Italian case appears interesting to explore, and it can allow inferring some first insights useful for a wider reflection on BCs’ impact reporting. Therefore, the present study aims to highlights some implications in terms of policy-making and standard-setting on BCs’ impact reporting in Italy and, more extensively, in the European context.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The second section presents the institutional and theoretical background of the research regarding BCs and, in detail, Italian BCs. The third section describes the research design, the applied methods, and the characteristic of the sample. The fourth section presents and discusses the findings of the research, while in the last section, some implications, conclusions, and inspirations for further research are presented.

2. Benefit Corporations and the Need for Accountability

The legal form of BC was introduced by several USA states—starting from 2010 by Maryland—into their legal framework to offer new instruments to entrepreneurs that want explicitly combine economic and social/environmental goals. As asserted by Wolf, the legal form of BC is «[…] an explicit attempt to suggest that ethical behavior and economic behavior need not be counter-posed to one another, with the added feature that it highlights the fact that anyone who chooses the traditional corporate form over the benefit corporation has made an explicit choice to privilege the profit-motive above all other motives» [17]. In the USA—or better in several USA—the normative process conducted to legislation on BCs was marked by a shift of responsibility about public interest from the public to the private sphere, in a neoliberal context [18]. On the other side, the legal form of BC is also the answer to the need for evolution of corporate legislation that includes a broader view of the purpose of the firms [19].

From a managerial perspective, BCs can be viewed as hybrid organizations [11,20], entities that contemporary pursue economic goals and social aims, combined in different forms. The purpose of hybrid organizations is typically blended, and it can be pursued by both for-profit firms that enlarge their objectives and nonprofit organizations by adopting commercial strategies in addition to institutional activities. BCs are for-profit organizations, but in these firms, profit-seeking is moderate by other goals, and the whole of different aims is at the center of the pursued “benefit” in a transformative way [21]. Economic and social/environmental goals can produce some tensions in the day-by-day life of BCs, and one of the significant challenges of BCs management lies in harmonizing different goals [22,23,24].

The introduction of BC as a new legal form was preceded in the USA by the B Corp movement that proposed a new vision of the relationship between business and society by starting from the goals of corporations and building a network of social-oriented for-profit firms [25]. B Corps are firms certified by a nonprofit organization named B Lab about their social and environmental performance. In detail, B Lab measures the score of corporations adopting the evaluating model of B Impact Assessment (BIA) that considers indicators about governance, workers, community, and environment and contributes to developing a social-oriented business model [26,27]. B Corps do not adopt a homogeneous legal structure, but they have to reach a minimum score of BIA to be allowed using the title of Certified B Corp, while during the assessment process, they can use the title of Pending B Corp. Previous studies showed that in the medium-long term, B Corps maintained their social and environmental commitments without renouncing to profitability [28].

The differences between B Corps and BCs are remarkable, above all, about the source of legitimacy. Indeed, while B Corps demonstrated social and environmental performances before becoming B Corps, BCs adapted their legal status only based on formal commitment. As shown in the following paragraphs, BCs have duties about reporting on their social impact, but there is no independent evaluation of their performance. This difference makes relevant the open discussion about the impact reporting of BCs.

From a formal/legal perspective, BCs are one the answers to the need for new organizational forms that allow the development of social business by moderating profit-seeking—without renouncing to it at all—and enhancing social and environmental aims. This need is generalized, but it is particularly strong in these institutional contexts where shareholder primacy is the prominent cultural heritage that limits the diffusion of corporate social responsibility practices among corporations [29]. With specific regards to the USA experience, some scholars, such as Esposito [30], defined BCs as an “optimal” answer because these organizations do not have to renounce to profit, even though they are obliged to integrate stakeholders’ perspective in their strategy. Besides, Hiller affirmed that the BC statute has the power of releasing managers from the unique view of shareholders’ paradigm and fostering the integration of corporate social responsibility into managerial practices [24]. On the contrary, other scholars, such as Yosifon [31] and Murray [32], considered BCs only one option that social-oriented entrepreneurs can adopt and called for a clarification of corporate governance legislation to avoid that stakeholders’ orientation was limited to BCs.

The Italian—and, partially, the European—institutional context in which new legislation about BCs was introduced is profoundly different from the USA. In Italy, a long tradition about the social vocation of business had already been established since the early birth of scientific debate about the nature of the firm and its role in society [33]. Italian “Economia Aziendale”—the science that combines managerial, accounting, and organizational studies—defined business as an instrument of diverse objectives—among which profit—that reflects a broad spectrum of human needs and values [34,35]. Shareholder primacy was not at the center of the vision of the firm, and a specific ethical approach to the relationship between business and society was cultivated [36].

Even Italian legislation considered hybrid forms of business, such as cooperatives, social cooperatives, and social enterprises, before introducing the BCs legal form. In detail, social cooperatives were considered by previous literature as examples of social enterprise [37,38] or hybrid organizations [39] and were largely widespread in Italy, above all in some industries such as health and education services and work integration since the nineties [40]. Nonetheless, while all legal forms characterized as “social” were classified as nonprofit based on the prohibition of the distribution of profits, the introduction of BC (“società benefit” in Italian) was a novelty in the Italian and European scenario, given that Italy was the first country after the USA to introduce this legal form. The new legal form was inspired by USA experiences [41], and it was introduced by the Law 28-12-2015 n. 208-376-384, which came into force toward January 2016. The aim of the Law was to introduce an option for the for-profit companies to choose an institutional architecture that makes explicit their purpose of creating benefit in a responsible, sustainable, and transparent manner. The Law expressly referred to diverse stakeholders, such as employees, customers, suppliers, and civil society, as addressees of value [42].

The norms devoted to regulating Italian BCs are very concise, and the legal requirements to become BCs are very scarce: they only have to adapt their statutes to make explicit the goals of benefit, to make strategies compliant to this social commitment (that can be quite vague), and to publish yearly a report about their impact. On the one hand, some scholars enlightened some fragilities of these new norms as it had already done for the discipline of some USA states [41,43]; on the other hand, the scarcity of the norms stimulated self-discipline by trade associations [44,45].

Previous studies focused on some crucial aspects of Italian BCs. For example, Testi and colleagues analyzed BCs as an enlargement of the social enterprise sector and an integration between for-profit and nonprofit sectors in welfare state evolution [46]. Besides, Mion and Loza Adaui explored purpose declarations of Italian BCs and showed some drivers and contents of the “benefit” pursued by these firms [47]. More studies analyzed Italian certified B-Corps to explore their business models and how public interests are combined with private/economic interests [48,49].

One of the crucial points that emerged by previous studies—both on American and Italian cases—is the accountability of BCs that is fundamental to make clear if and how BCs effectively create a social benefit and to guarantee public trust in BCs. As mentioned above, the publication of an annual report about the impact generated by BCs is mandatory in Italy, but, to the best of our knowledge, no study has explored if BCs publish a report, the characteristics of these impact reports, and their quality.

The needs for BCs’ transparency about their social impact derive from different factors that were highlighted by previous literature, and that is one of the critical points in early legislative experiences in the USA [19]. First, the notion of “benefit” is related to the public interest and, consequently, there is a link between BCs and public policy in order to guarantee (public) trust in these organizations [50]. To avoid any form of greenwashing and make BC an effective form of social business [51], in the USA, as in Italy, the legislation on BCs imposes forms of reporting about social impact. Nonetheless, only some USA states dictate some consequences for BCs that do not publish impact reports [52], and also in Italy, the Law is quite vague about these consequences, even though they are compared to misleading advertisements. In general, greenwashing is a form of market perturbations, and concerns about greenwashing behaviors are typical of reporting on sustainability so much that both legislations and scholars have focused this topic as one of the main relevant in the field of social accountability [53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. The concern about greenwashing was also enforced by previous deleterious cases—such as Volkswagen [60]—and the mandatory publication of impact report by BCs was also imposed to avoid destructive behaviors by organizations that adopted a legal form devoted to social goals. Some scholars highlighted that, in the absence of satisfactory accountability, BCs could paradoxically enlarge the greenwashing phenomenon and limit socially responsible behaviors [61].

Second, accountability can be fundamental to fill the gap in understanding the goals of BCs and their effectiveness in the public interest [62]. As highlighted by Cetindamar [63] for American BCs, the public declarations of the purpose of BCs are often not fully compliant with the Law, and several firms do not declare which are their economic, social, or environmental goals. Mion and Loza Adaui [47] showed that also Italian BCs are quite vague in their public declaration and detecting the real impact of BCs is not simple. Consequently, transparency about the performances and the level of social impact is essential not only to evaluate the “goodness” of the single BC but also to understand how these organizations contribute to the public interest and common good.

Third, the need for transparency emerged from a managerial perspective. After the diffusion of BCs among the USA (and among other countries, first of all, Italy), a need for clarity emerged about the capacity of BCs in concretizing their hybrid goals into tangible benefit and profit performance. If BCs have a potential cultural role of market-changer [64], this role is affected by the effectiveness of their blended purpose. The evident tension between economic and social/environmental goals is at the very center of BCs management [65], but if this tension is well managed, it is the primary driver of success for these organizations. BCs need to emerge their hybridity “in practice,” which is in the concrete ability to purse combined goals by harmonizing potentially conflicting stakes.

Furthermore, stakeholders’ specific information needs to expand the importance of transparency about the impact of BCs. For example, financial advisors can be interested in BCs given that financial markets are giving growing attention to sustainable investment; nonetheless, the formal condition of BCs is not enough to ensure that their performances are effectively capable of creating a positive social or environmental impact. Indeed, the hybrid nature of BCs can facilitate opportunistic behaviors in favor of shareholders’ interest or, on the contrary, neglect the expectations of shareholders in the name of benefit goals. Consequently, financial advisors need to have instruments to understand BCs and their performances to promote investments in these organizations [66].

Finally, the importance of accountability and the quality of reports is confirmed by a large body of literature that focused on the topic of quality of sustainable/social reporting [67,68], even though these studies did not specifically explore the case of BCs. Several scholars highlighted that quantity of disclosed information does not ensure the quality of reporting and cannot be considered satisfactory to the needs of stakeholders [69], and quality is related to other dimensions of reporting such as the adoption of guidelines, the readability of the documents, or the clarity of information [70]. Despite the variety of methods adopted and the results achieved by these studies, the importance of quality reporting emerged as a crucial factor to gain stakeholders’ legitimation and cultivate good relationships with them [71,72,73].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

The research focused on the mandatory publication of social reports by Italian BCs to understand if these organizations were compliant with the normative requirement, which were the main practices in reporting, the quality of impact reporting, and the determinant of quality. The study was exploratory in nature, and it aimed to fill the gap in the literature about impact reporting of BCs and contribute to the increasing discussion about BCs’ role in society and, above all, about their impact reporting.

In detail, the study aimed to answer three related research questions:

- (1)

- Did Italian BCs publish impact reports in compliance with normative requirements?

- (2)

- Which were the main characteristics of these reports?

- (3)

- Which was the quality of these reports, and which were the main determinants of reporting quality?

To answer to the abovementioned questions, the research design adopted a mixed qualitative, and quantitative approach. In detail, after the definition of the sample of analysis (see the following Section 3.3), websites of BCs were analyzed to understand if these organizations effectively published an impact report. Second, a content analysis was performed to impact reports to gather information and data about reporting practices and to evaluate the quality of reporting. The quality evaluation was performed by applying an evaluation scale—based on previous literature and normative requirements—that is presented in the following subparagraph. Content analysis is a technique largely adopted to explore reporting practices [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] and evaluate reporting quality [79,83,84,85]. The aim of the evaluation scale was overcoming a narrow view of reporting quality based only on the quantity of information disclosed, that previous studies underlined as an unsatisfactory proxy of quality [86,87]. Finally, the results of content analysis were explored by applying statistical methods aimed to understand the determinants of reporting quality.

3.2. Evaluation Instrument

To answer research question n. 3 and appreciate the quality of impact reports, an evaluation instrument based on previous literature was adopted. The notion of reporting quality is not unanimously accepted in literature, but it is mostly recognized that quality is multidimensional, and it is appropriately valuable only by a compound approach that considers different aspects of reporting [74,85,88,89,90,91,92]. In detail, according to Helfaya and colleagues [69], reporting quality is the combination of three characteristics: content (the preponderant one), credibility, and communication. As done by previous studies such as one by Sierra-Garcia and colleagues [92] in similar situations, the evaluation instrument adopted in the present research was designed on the content of § 382 of the article 1 of Law 28-12-2015 n. 208. Furthermore, the evaluation instrument took into account the abovementioned three dimensions of contents (as required by the Law), credibility (understood as the adoption of an external standard in preparing the report), and communication, defined by the availability of the report on the website and the readability. The evaluation instrument included ten indicators (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Instrument for the analysis of impact report quality.

A rating scale was developed to assign points to each indicator. This rating scale—built based on previous literature [93,94]—allows evaluating the indicators according to the numeric relevance disclosed in Table 2. The evaluation scale was designed to avoid the risk of considering only quantitative aspects of impact reporting, and to deepen the quality of each indicator.

Table 2.

Evaluation scale.

The minimum score was 0 (for BCs that did not publish an impact report on the website), while the maximum possible score was 40. It is to remark that the score of 4 points in each indicator was reserved for exceptional disclosure or an innovative way to explain.The application of the evaluation scale for indicator n. 9 (adoption of external standard) took into account the degree of adoption, while for indicator n. 10, the number of clicks necessary to reach the report and the use of tables, graphics, and figures were considered to assign the score. As suggested by previous literature [95], the evaluation procedure started with a pilot study that involved 20 reports. Each impact report was considered separately to assign a score about its quality. Then, to reduce the subjectivity of the evaluation, a cross-check analysis was performed by the author and by another researcher, called to supervise and verify the procedure. After the pilot study, some discrepancies between the two researchers were detected, discussed, and reconciled.

Furthermore, in order to verify the reliability of the scale, the results of the content analysis were verified by applying Cronbach’s alpha, as suggested by Krippendorff [96]. According to the literature, the reliability is confirmed if Cronbach’s alpha shows values in the range of 0.7–0.95 [97,98,99]. In this case, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.904 and confirmed the reliability of the adopted scale.

3.3. Sample of Analysis

The sample of analysis was built, starting from the data available into the AIDA-Bureau Van Dijk database in July 2020. The database included 328 benefit corporations, but some of them were excluded from the analysis. In detail, 19 BCs were excluded because they were ceased, failed, or in liquidation; consequently, they were not obliged to publish an impact report, and the analysis of these BCs would have been not significant for the aims of the study. 63 BCs were founded during the last year, and they also were not obliged to publish impact reports; finally, for 54 BCs, there was no valid information. Consequently, the sample of analysis included 192 BCs. 48 BCs had no active website, and the content analysis was performed on 148 BCs’ website and on 47 impact reports that could be found on these websites. There was impossible to find an impact report on 101 websites.

Some key data were collected from the AIDA-Bureau Van Dijk database, useful to the analysis of the determinant of impact reporting quality. In detail, the following data were collected: geographical site, industry, total earnings, and profitability (measured as return on assets). Furthermore, by analyzing the B-Lab database, the certifications B-Corp were also explored.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Impact Reporting Practices

The clause 383 of article 1 of Law 28-12-2015 n. 208 imposes the mandatory publication of an annual impact report on the website of the BCs if this website exists. The content analysis of 192 BCs highlighted that 144 BCs had an active website in July 2020, but only 47 published online a report (32.64% of BCs with an active website). It was impossible to verify if BCs without an active website published the annual report. Furthermore, several BCs did not publish the report pertinent to 2019, while some BCs disclosed online only the 2017 impact report. These findings were really surprising because of the mandatoriness of the yearly preparation and publication on the website of an impact report. Table 3 shows the distribution of impact reports for years of competences and the number of needed clicks to reach the impact report on the website.

Table 3.

Reports for the year of competences and number of clicks.

Observed data showed a low degree of compliance by Italian BCs about the compulsoriness of both the publication of the impact report on the corporate website and the annual frequency. Even though the 2019 reports had to be prepared during the COVID-19 pandemic emergency 19 and some delay could be expected, the evidence remained strong about the insufficient attention paid by BCs to accountability. These findings were surprising not only because of the mandatoriness of the publication of impact report but also because BCs should be firms with a clear social purpose and, consequently, with a strong commitment to transparency and sharing of impact performance. The Law did not discipline the control system and responsibility on BCs’ impact report. This absence could be one of the motives of quite a narrow number of compliant BCs, together with the scarce experience on BCs’ impact evaluation.

Regarding the accessibility of information, the content analysis disclosed that most published impact reports could be easily detected on the website. Indeed, 28 impact reports (59.58%) could be found by one or two clicks, while only 4 cases required more than three clicks. As highlighted by previous literature [100], also for Italian BCs’ case, the accessibility of impact reports was influenced by the primary purpose of the website, above all for those BCs that adopt the website for retail or presenting products or services to their actual or potential customers. Furthermore, only one BCs adopted an interactive form of impact report that allowed the reader the free navigation among the contents, while the other ones published the report as a pdf file with limited adoption of navigation or feedback instruments (such as links or online survey). The analyzed BCs were often small or medium-sized companies. They were pioneers in impact reporting: their reporting and disclosing practices on the web are partially poor and confirmed previous studies on sustainability reporting in the early stage of evolution [100,101,102].

About methodological aspects, the content analysis made clear that the reporting practices were very various, starting from the wording of the published documents. Even though the largest part of the reports was named “impact report”—often by explicitly referring to normative requirements—there were several other titles for the report: “social report,” “sustainability report,” “integrated report,” or “interdependence report.” The titles mirrored the standards adopted for report preparation; in detail, the “sustainability report” referred to the GRI standard, while the “interdependence report” referred to the adoption of the declaration of the interdependence of B Corps.

Nonetheless, using a national or international external standard to prepare the report and evaluate the impact was relatively low. Table 4 summarizes the external standard adopted by Italian BCs, by separating the standards used for the evaluation of impact (such as the Benefit Impact Assessment—BIA) and the standards used to prepare the reports and present the performance (such as GRI Guidelines and SDGs). Some reports referred to more than one standard, while many did not refer to any standard.

Table 4.

Adoption of external standards.

Many BCs adopted the BIA Standard to testify their social impact, even though a part of them (3 BCs) did not gain the minimum score of 80 on 200 established by B Lab as the minimum level to become Certified B Corp. Nonetheless, in many cases, there was no comment about the BIA score, and BCs did not disclose the factors that determined their impact. Indeed, only 2 BCs disclosed their partial scores about the sub-dimensions of the four aspects of impact valued by the BIA (governance, workers, community, and environment). The extensive adoption of BIA was easily predictable because of the logical (even though not formal) relationship between being a BCs and the certification B Corp, and several analyzed BCs were certified B Corps. However, as underlined by previous literature, the BIA use alone was not a guarantee of neither the quality of external communication [103] nor the sustainable growth of the company [104,105], even though other studies—such as this by Gazzola and colleagues [106]—underlined the significance of BIA for the social and financial performance of BCs.

Despite a large literature and practice about different models and instruments adopted to evaluate social impact in general [107,108] and of social-oriented firms in particular [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117], the content analysis showed that Italian BCs were inspired mainly by the B Corp experience and they modeled their impact evaluation on the BIA model. A reason for this choice could be detected in Annex 5 to 383 of article 1 of Law 28-12-2015 n. 208 that reproduced the impact area of BIA in the guidelines of the impact evaluation of BCs. Nonetheless, this finding was partially unsatisfactory in terms of the potential contribution that BCs could give to social development. The present study underlined that the absence of a profound reflection on measurement methods brought out a partially unexplored understanding of the “impact” of BCs. Apart from some sporadic cases, into the analyzed reports, social impact was not well defined, but it was considered as the mere ability to achieve organizational goals. On the contrary, in literature, social impact was defined as “significant or lasting changes in people’s lives, brought about by a given action or series of action” [118], as “the extent to which that change arises from the intervention” [119], or as “the difference between the outcome for participants, taking into account what would have happened anyway, the contribution of others and the length of time the outcomes last” [120]. The content analysis brought out that several BCs developed a narrow vision of “impact” that limited also reporting practices.

On the side of reporting standards, the findings were very scarce: only a few BCs prepared their impact report based on external standards such as GRI ones [121], only one BC published an integrated report based on Integrated Report Framework [122], and seven BCs decided to present their social impact by making reference to SDGs [123]. Several reports were prepared with a free form and did not make explicit if they adopted a methodological approach. The lack of a transparent reporting methodology can be considered a crucial point of weakness for the accountability of BCs. In addition to those that explicitly adopted the GRI standard, only two impact reports analyzed the materiality of reported issues and explained a stakeholder engagement process. On the contrary, previous literature on social/sustainability reporting was unanimous in considering the importance of stakeholder engagement to make sure that reports effectively disclosed corporate performance [124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133]. In this regard, the findings of the present study underlined the need for the creation of a more robust reporting culture in BCs and the methodological improving impact reporting practices.

On the side of the content of impact reports, the methodological lack caused a huge variety of choices that allowed detecting some good practices and a widespread need for improving the impact reporting process. The content analysis showed that in the absence of normative guidelines and of the adoption of external reporting guidelines, BCs interpreted the normative requirements about the content of impact reports in a very different way. First, the Law required presenting the goals of the company. Nonetheless, several BCs disclosed their goals only by reproducing the declaration of the corporate objective without detailing specific planned goals and targets. In consequence, there was no clarity about the operationalization of corporate purpose in specific benefit goals. These findings confirmed findings of previous literature—on both the American [61] and the Italian case [47]—about the vagueness of purpose declaration of BCs that were not able to make explicit how “benefit” could be made in practice.

Second, the Law required disclosing obstacles that limited the pursuing of benefit goals. This requirement could be considered as “eventual,” but it was quite normal that not all the planned goals could be reached during the year. 11 BCs disclosed some information about the reasons that restrained the planned benefit activities or limited the achievements of the benefit objectives, while the other 36 analyzed impact reports did not contain information about this point. Some impact reports presented good practices by detailing, for each goal, the level of achievement, and, when the target was not reached, the reason for the failure to achieve.

Third, the content analysis focused on the required information about BCs performance on the four fields prescribed by the Annex 5 to 383 of article 1 of Law 28-12-2015 n. 208: governance, workers, other stakeholders, and the environment. Some BCs choose to illustrate their impact on specific fields or specific stakeholders, while others narrated their performance about all the expected categories of stakeholders as prescribed by the Law. In the absence of materiality analysis, the choice of reported areas was not disclosed: in some cases, the impact areas were chosen according to the declared benefit purpose, while in other cases, the exclusion of one or more impact areas was not clarified. When the BCs included the BIA score into the report, an evaluation of all the impact areas was implicitly done. Nonetheless, in several impact reports, no information was present about activities and performances that allowed achieving this score. Furthermore, the content analysis showed the scarce adoption of quantitative indicators such as GRI indicators or other KPI in favor of a narrative approach to impact evaluation. On the one hand, these findings underlined the absence of detailed guidelines about the content of impact reports and specific normative requirements about quantitative analysis of impact. Without a homogenous set of indicators, the comparability of impact reports proved to be very low, and the quality of accountability was quite unsatisfactory compared with other reporting practices [83,134]. On the other hand, as underlined by Whitehead [133], without a careful materiality analysis, the use of indicators could be not significant and self-referential.

Finally, the content analysis focused on the disclosure of new goals that BCs intended to pursue during the next year(s). Apart from five cases, all BCs were compliant with the normative requirement about disclosing new goals. As was easily predictable, this section was strictly correlated to that one devoted to disclosing corporate goals, and the level of transparency about new goals was in line with past goals disclosure. Some BCs decided to make explicit, specific targets related to goals and future planned actions, while several impact reports displayed only generic commitments.

4.2. Impact Reporting Quality

As mentioned above in the methods section of the paper, the impact report quality was evaluated by applying the evaluation model to impact reports. The analysis included all the 47 reports, even though they did not refer to the same year of competence, because the content analysis aimed to measure the quality of the document and did not compare performances. The evaluation instrument could be applied to all the impact reports, and Table 5 shows some data of descriptive statistics of impact reporting quality about the entire sample and sub-groups of BCs (Certified or non-Certified B-Corps, native and non-native BCs, and BCs that prepared the report by applying an external standard for the impact evaluation and/or reporting).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of impact reporting quality.

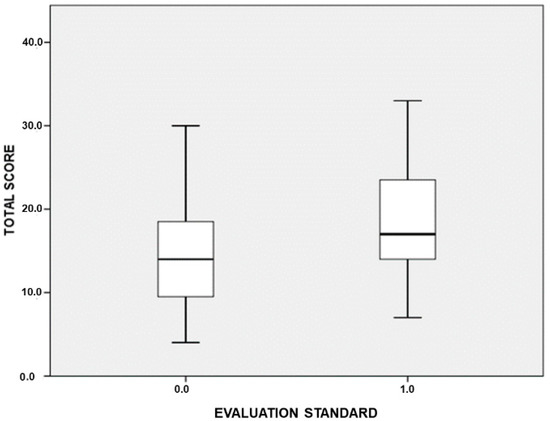

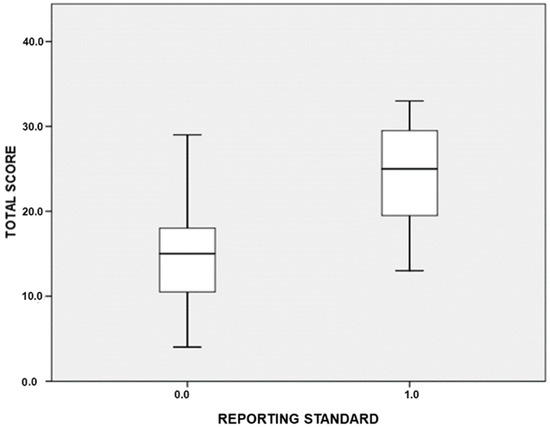

The observation of data and the means highlighted a critical difference in the quality score between BCs that adopted external standards and BCs that prepared their reports without referring to any guideline. Furthermore, the adoption of reporting external standards appeared a more potent as a driver of quality than the adoption of impact evaluation standard (that is, in almost all cases, the BIA). This finding is related to what emerged by the qualitative content analysis described in the previous subparagraph. The effect of the adoption of an external standard on reporting quality also emerged by observing the median value as showed by Figure 1—referred to impact evaluation external standard—and Figure 2, relating to reporting external standard.

Figure 1.

Box-plot of impact reporting quality score for BCs that adopted or non-adopted impact evaluation external standard.

Figure 2.

Box-plot of impact reporting quality score for BCs that adopted or non-adopted reporting external standard.

To deepen this finding, a Mann-Whitney U-test [135,136,137] was applied to verify if there was a significant difference between the impact reporting quality score of BCs that applied an external standard of impact evaluation or reporting. The test showed a relevant difference with a high level of significance (p-value < 0.001). Nonetheless, applied to separate groups based on the type of adopted external standard, the U-test showed a relevant difference only for BCs that used a reporting external standard (p-value < 0.001). At the same time, there was no significant difference in impact quality score between reports prepared with or without impact evaluation standard. Furthermore, the Kruskal-Wallis test verified the findings with a satisfactory level of significance (p-value < 0.005) if applied to the groups with an external standard and without it. As the previous test, also Kruskal-Wallis test [138] was applied, and it confirmed the high significant difference in impact quality score determined by the adoption of reporting external standard (p-value < 0.001).

In contrast, the use of impact evaluation standards did not cause a significant difference in the scores (p-value > 0.1). These findings confirmed that applying an external standard is a crucial factor in promoting the quality of reporting and, indirectly, the level of accountability of BCs. Even though the disclosure of the BIA score could be considered an instrument to measure and testify the social and environmental performance of BCs, this standard appeared as unsatisfactory in terms of reporting quality. The double adoption of evaluation and reporting external standards had also to be highlighted: the five BCs that made this choice prepared impact reports with very high-quality scores in the range 20–33 and could be considered as good practices. These findings were in line with previous literature on corporate social responsibility/sustainability reporting that highlighted that the application of mandatory [139,140] or voluntary [141] standards affected reporting quality. Furthermore, the previous study by Meyskens and Paul [142] agreed that the voluntary adoption of a largely recognized standard or guidelines was an essential factor of reporting quality, but it showed that companies adopted this practice overtimes. In this regard, it is remarkable that the largest part of analyzed impact reports was the first experience of reporting for BCs, and a gap in reporting quality could be reasonably expected.

Finally, the results of impact reporting quality evaluation were analyzed by applying some statistical tests on correlation to verify if there were some significant determinants of reporting quality. In detail, Spearman Rho and Kendall Tau tests—that were considered robust tests as nonparametric correlation estimators [143]—were applied. The analysis focused on both determinants broadly adopted in literature as reporting quality determinants [67,68] and other ones identified explicitly to the reality of Italian BCs. In detail, the analyzed determinants were the followings:

- The geographical area in which the BCs had their headquarter in consideration of the difference in economic and entrepreneurial development among different areas [144]. This determinant was built by dividing the Italian territory into four areas as usually done for statistic and social studies by the Italian National Institute of Statistics [145];

- B-Corp certification, that was considered as a dummy variable, i.e., 1 for BCs that had achieved the certification and 0 for BCs that had no certification or were pending B-Corps;

- Native or non-native BCs, that was also considered as a dummy variable, 1 for BCs that were founded in the present form and 0 for companies that changed their legal status in BC after their foundation. Even though this variable was correlated to the age of the company considered that the Law n. 208 entered into force only from 2016, it had to be considered a different variable, typical of Italian BCs;

- Industry: it was a variable adopted largely in previous studies on reporting quality [75,141,146,147,148,149,150]. The diverse industries were grouped in three clusters: agriculture (to which the value 1 was assigned), manufacture (value 2), and services (value 3);

- Profitability, expressed as a proxy by the Return On Asset index, in line with previous studies that adopted this indicator and analyzed its correlation to reporting quality [78,90,150,151,152];

- Corporate size, expressed as total revenue [141].

Table 6 shows the results of the Spearman rho correlation test, and Table 7 shows the results of the Kendall tau test.

Table 6.

Spearman rho correlations.

Table 7.

Kendall tau correlations.

The findings of the correlation analysis were quite poor but allowed some first insights. Indeed, the analysis demonstrated a relevant correlation only between corporate size and impact reporting quality, while the other determinants were not significantly correlated with the impact reporting quality score. Regarding corporate size, the findings were in line with previous studies such as those by Michelon et al. [141] and by Brammer and Pavelin [153]. On the contrary, the irrelevance of the other determinants was unexpected and not in line with previous experiences. Nonetheless, the tests’ results have to be understood in light of the novelty of impact reporting for Italian BCs. Despite the mandatoriness of impact reports publication, the relatively low number of BCs that effectively published the impact report affected the analysis. These BCs seemed real “pioneers” of impact reporting practice, and probably the quality of their reports was influenced by their commitment more than by institutional or economic determinant. The analysis brought to light some “good pioneers” that established appreciable reporting practices and other BCs that did not yet cultivate a developed accountability culture. Further research could be able to deeply explore the determinant of impact reporting quality when the practices are extensive.

5. Conclusions

Impact reporting practices are at a very early stage of evolution because of the novelty of the Law that introduced the BCs legal status in Italy. This research aimed to explore impact reporting practices by Italian BCs and evaluate the quality of impact reports as a crucial determinant of BCs accountability. The findings of the content analysis and the quality evaluation highlighted some critical points that can contribute to the development of existing literature on BCs and on reporting quality. However, they also can suggest some practical implications for BCs manager, policy-makers, and standard setters.

The analysis showed a low level of compliance by Italian BCs in publishing a yearly impact report. Furthermore, the reporting practices turned out to be significantly differentiated in terms of both content and methodological aspects. The absence of a generally recognized external standard and, probably, of a stringent control allowed to each BC interpreting impact reporting in different manners. Indeed, while some impact reports were prepared by applying an external standard and proper methods (e.g., materiality analysis) and including all required contents, many other reports appeared very poor and potentially unable to give a transparent and accountable image of BCs performance. The analysis of impact reporting quality allowed deepening the content analysis by confirming the crucial role of external standard in promoting reporting quality, while other factors—such as the B Corp certification—seemed to be irrelevant on reporting quality. Furthermore, statistical analysis showed that impact reporting quality was correlated only to corporate size, while it was not significantly correlated to other determinants considered by previous studies on corporate social responsibility/sustainability reporting.

Under the theoretical perspective, this study confirmed the crucial role played by impact reporting to improve the accountability of BCs. Normative compliance alone did not produce generalized impact reporting practices that probably could be fostered by other determinants such as organizational culture or stakeholder engagement. Furthermore, the study deepened the notion of reporting quality by applying the evaluation model on an unexplored reality. The findings confirmed the importance of an external standard to promote reporting quality but did not prove a significant correlation between reporting quality and other determinants such as profitability, external certification, or industry.

Some practical implications derived from the findings. The study suggested to managers the need for an external standard or, at least, the adoption of some crucial instruments proposed by standard (such as stakeholder engagement and materiality analysis) to improve the quality of impact reporting. Furthermore, managers can understand the importance of a clear statement of which impact the BCs aim to achieve for improving their accountability and, in a medium-long time perspective, their legitimacy among stakeholders.

Furthermore, the study can suggest to policy-makers increased attention in defining the characteristics and the requirements of impact reporting to avoid excessive inhomogeneity among impact reports and to promote the comparability of these reports. Policy-makers can also improve the forms of external controls on compliance of BCs about the mandatory publication of impact reports, for example, by establishing a public register of BCs impact reports. Finally, standard setters can promote the publication of standards devoted to BCs by adapting existing standards, detailing them, or producing new specific standards.

The study has some limitations that also open for further research. First, the study could appreciate impact reporting practices only in their early stage and analyzed only one edition of the reports. Future longitudinal studies will better understand the determinant of impact reporting quality and appreciate the improvement path of BCs. Second, the study focused on the mandatory contents of impact reports, while future research will understand the different reporting practices by deepening voluntary contents, such as the contribution of BCs to the achievement of SDGs. Finally, further research could explore the relations between reporting quality and social/environmental performance of BCs, including those measured by BIA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Williams, F. The business case for purpose. In Perspectives on Purpose; Taylor & Francis: Milton, UK, 2019; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, C.A.; Ghoshal, S. Changing the role of top management: Beyond strategy to purpose. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1994, 72, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.; Van den Steen, E. Why do firms have “purpose”? The firm’s role as a carrier of identity and reputation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; Thakor, A.V. Creating a purpose-driven organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2018, 96, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The big idea. How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Roundtable. Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation; The Business Roundtable: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muff, K.; Kapalka, A.; Dyllick, T. The Gap Frame—Translating the SDGs into relevant national grand challenges for strategic business opportunities. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Whiteman, G.; Parker, J.N. Backstage interorganizational collaboration: Corporate endorsement of the sustainable development goals. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Van Zanten, J.; Van Tulder, R.; Van Zanten, J.A. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2018, 1, 208–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M.; Walker, J.; Dorsey, C. In search of the hybrid ideal. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2012, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Hoffman, A.J. The new heretics: Hybrid organizations and the challenges they present to corporate sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexius, S.; Furusten, S. Enabling sustainable transformation: Hybrid organizations in early phases of path generation. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Varon Garrido, M.A. Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. J. Bus. Strategy 2017, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Walker, J.; Bacq, S.; Kickul, J. Hybrid organizations: Origins, strategies, impacts, and implications. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. The economy effect: Conceptual innovation and benefit corporations. New Polit. Sci. 2018, 40, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudot, L.; Dillard, J.; Pencle, N. The emergence of benefit corporations: A cautionary tale. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deskins, M.R. Benefit corporation legislation, Version 1.0—A breakthrough in stakeholder rights? Lewis Clark Law Rev. 2011, 15, 1048–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing research on hybrid organizing—Insights from the study of social enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.L.; Kahn, W.N. The hijacking of a new corporate form? Benefit corporations and corporate personhood. Econ. Soc. 2016, 45, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Strategies, practices, and tensions in managing business model innovation for sustainability: The case of an Australian B Corp. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing social-business tensions: A review and research agenda for social enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2018, 233, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, J.S. The benefit corporation and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Klaber, A.; Thomason, B. B Lab: Building a new sector of the economy. Harv. Bus. Sch. Case 2011, 411047, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Villela, M.; Bulgacov, S.; Morgan, G. B Corp certification and its impact on organizations over time. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Beveridge, A.J.; Haigh, N. A configural framework of practice change for B Corporations. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. Evaluating CSR accomplishments of founding certified B Corps. J. Glob. Responsib. 2015, 6, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C.; Rönnegard, D. Shareholder primacy, corporate social responsibility, and the role of business schools. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, R.T. The social enterprise revolution in corporate law: A primer on emerging corporate entities in Europe and the United States and the case for the benefit corporation. William Mary Bus. Law Rev. 2013, 4, 639–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yosifon, D.G. Opting out of shareholder primacy: Is the public benefit corporation trivial? Del. J. Corp. Law 2017, 41, 461–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Murray, J.H. Choose your own master: Social enterprise, certifications, and benefit corporation statutes. Am. Univ. Bus. Law Rev. 2012, 2, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Garzella, S. L’azienda e la Corporate Social Responsibility. Approfondimenti Dottrinali e Riflessioni Gestionali; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2018; p. 124. ISBN 9788891784131. [Google Scholar]

- Coda, V. Valori imprenditoriali e successo dell’impresa. In Valori Imprenditoriali e Successo Aziendale; Bellante, F., Bertini, U., Butta, C., Coda, V., Cricchio, S., Lipari, C., Miraglia, R.A., Modica, M., Schillaci, C.E., Sorci, C., et al., Eds.; Giuffrè: Milan, Italy, 1986; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Coda, V. Il bene dell’impresa, bussola per comportamenti responsabili. In Valori d’Impresa in Azione; Coda, V., Minoja, M., Tessitore, A., Vitale, M., Eds.; EGEA: Milan, Italy, 2012; pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Signori, S.; Rusconi, G. Ethical thinking in traditional italian economia aziendale and the stakeholder management theory: The search for possible interactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 89, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Fundamentals for an international typology of social enterprise models. Voluntas 2017, 28, 2469–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences. J. Soc. Entrep. 2010, 1, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G. La cooperazione sociale: Un modello di hybrid organization? In Tra Economicità e Bene Comune. Analisi Critica delle Cooperative Sociali Come Hybrid Organizations; Broglia, A., Corsi, C., Farinon, P., Mion, G., Eds.; RIREA: Rome, Italy, 2017; pp. 49–89. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. The rise of social cooperatives in Italy. Voluntas 2004, 15, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolfo, G. The new Italian benefit corporation. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2019, 21, 279–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, M. L’interesse sociale: Dallo shareholder value alle società benefit. Banca Impresa Soc. 2017, XXXVI, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, S. Le società benefit nell’ordinamento italiano: Una nuova “qualifica” tra profit e non profit. Nuove Leggi Civ. Comment. 2016, 39, 995–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Assonime. La Disciplina delle Società Benefit; Assonime: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, M.; Sertoli, C. Una ricerca Assonime sulle società benefit. Dati empirici, prassi statutaria e prospettive. Anal. Giuridica Econ. 2018, 1, 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Testi, E.; Bellucci, M.; Franchi, S.; Biggeri, M. Italian social enterprises at the crossroads: Their role in the evolution of the welfare state. Voluntas 2017, 28, 2403–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R. Understanding the purpose of benefit corporations: An empirical study on the Italian case. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M.; Agulini, A. Governance and accountability models in Italian certified benefit corporations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2368–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Acting as a benefit corporation and a B Corp to responsibly pursue private and public benefits. The case of Paradisi Srl (Italy). Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S.K.; Arsneault, S. The Public Benefit of Benefit Corporations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 51, pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stecker, M.J. Awash in a sea of confusion: Benefit corporations, social enterprise, and the fear of “greenwashing”. J. Econ. Issues 2016, 50, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, C. Benefit Corporation Reporting Requirements; Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. A Critical review of environmental sustainability reporting in the consumer goods industry: Greenwashing or good business? J. Manag. Sustain. 2013, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.S.; Thorne, L.; Cecil, L.; LaGore, W. A research note on standalone corporate social responsibility reports: Signaling or greenwashing? Crit. Perspect. Account. 2013, 24, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Montiel, I. When are corporate environmental policies a form of greenwashing? Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 377–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter “greenwashing”: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A.; Vollero, A.; Conte, F.; Amabile, S. “More than words”: Expanding the taxonomy of greenwashing after the Volkswagen scandal. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R. Benefit corporations at a crossroads: As lawyers weigh in, companies weigh their options. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R. Assessing the Accountability of the benefit corporation: Will this new gray sector organization enhance corporate social responsibility? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, D. Designed by law: Purpose, accountability, and transparency at benefit corporations. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, R. A new look at benefit corporations: Game theory and game changer. Am. Bus. Law J. 2015, 52, 501–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W. Examining the interplay of social and market logics in hybrid business models: A case study of Australian B Corps. In Sustainable Business Models: Principles, Promise, and Practice; Moriatis, L., Melissen, F., Idowu, S.O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Halsey, B.J.; Tomkowicz, S.M.; Halsey, J.C. Benefit corporation concerns for financial service professionals. J. Financ. Serv. Prof. 2013, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifka, M.S. Corporate responsibility reporting and its determinants in comparative perspective—A review of the empirical literature and a meta-analysis. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2013, 22, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M.; Alawattage, C. Exploring the quality of corporate environmental reporting Surveying preparers’ and users’ perceptions. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 32, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management: A stakeholder perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability ... and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Scherer, A.G. Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, C.K. The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. In Social and Environmental Accounting: Developing the Field; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 51–63. ISBN 1848601697. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and rehearsal of the method in a British-German context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M.; Van Velthoven, B. Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? Eur. Account. Rev. 2005, 14, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2011, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Monteiro, S.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. Determinants of environmental disclosure in the annual reports of large companies operating in Portugal. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G. The relevance of environmental disclosures: Are such disclosures incrementally informative? J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R. Mandatory nonfinancial disclosure and its consequences on the sustainability reporting quality of Italian and German companies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Abeysekera, I. Content analysis of social, environmental reporting: What is new? J. Hum. Resour. Costing Account. 2006, 10, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Petty, R.; Yongvanich, K.; Ricceri, F. Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting. J. Intellect. Cap. 2004, 5, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, N.; Northcott, D. Content analysis in accounting research: The practical challenges. Aust. Account. Rev. 2007, 17, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutantoputra, A.W. Social disclosure rating system for assessing firms’ CSR reports. Corp. Commun. 2009, 14, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R. The effect of mandatory publication of nonfinancial disclosure in Europe on sustainability reporting quality: First insights about Italian and German companies. In Non-Financial Disclosure and Integrated Reporting: Practices and Critical Issues; Songini, L., Pistoni, A., Baret, P., Kunc, M., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 55–80. ISBN 9781838679644. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, J. Methodological issues—Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2000, 13, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, S.; Bozzolan, S. Quality versus quantity: The case of forward-looking disclosure. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2008, 23, 333–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Staden, C.J.; Hooks, J. A comprehensive comparison of corporate environmental reporting and responsiveness. Br. Account. Rev. 2007, 39, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, H.; Zaman, M. Board gender diversity and sustainability reporting quality. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2016, 12, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tuwaijri, S.A.; Christensen, T.E.; Hughes, K.E. The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comyns, B.; Figge, F. Greenhouse gas reporting quality in the oil and gas industry: A longitudinal study using the typology of “search”, “experience” and “credence” information. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Garcia, L.; Garcia-Benau, M.A.; Bollas-Araya, H.M. Empirical analysis of non-financial reporting by Spanish companies. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hąbek, P.; Wolniak, R. Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszak, Ł.; Rózańska, E. CSR disclosure in Polish-listed companies in the light of directive 2014/95/EU requirements: Empirical evidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.W.; Milne, M.J. Exploring the reliability of social and environmental disclosures content analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1999, 12, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in content analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84787-907-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A.; Frost, G.R. Accessibility and functionality of the corporate web site: Implications for sustainability reporting. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2006, 15, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikhardsson, P.; Raj Andersen, A.J.; Bang, H. Sustainability reporting on the internet. Greener Manag. Int. 2014, 2002, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, C.; Godemann, J. Internet-supported sustainability reporting: Developments in Germany. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, G.; Michelini, L.; Grieco, C. Social impact and online communication in B-Corps. Glob. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 11, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gehman, J.; Grimes, M.G.; Cao, K. Why we care about certified B Corporations: From valuing growth to certifying values practices. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.C.; Gamble, E.N.; Moroz, P.W.; Branzei, O. The impact of B Lab certification on firm growth. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2019, 5, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Ratti, M.; Amelio, S. CSR and sustainability report for nonprofit organizations. An Italian best practice. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 5, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, M.J.; Bustelo, E.S. Social Impact Assessment and Monitoring: A Guide to the Literature; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, K.; Hooper, D.A.; Thompson, J.; Creighton, J. Guide to Social Impact Assessment: A Framework for Assessing Social Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rawhouser, H.; Cummings, M.; Newbert, S.L. Social impact measurement: Current approaches and future directions for social entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.D.; Beaton, E.; Haigh, N. Increasing social impact among social enterprises and traditional firms. In Handbook on Hybrid Organisations; Billis, D., Rochester, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, G. Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2009, 18, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.; Galimidi, B. Catalog of Approaches to Impact Measurement Assessing Social Impact in Private Ventures Version 1.1; Social Venture Technology Group with the support of The Rockefeller Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, R.; Hall, K. Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement: The opportunities and barriers for social enterprises in health and social care. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, J.; Kaminski, J.; Sodagar, B.; Khan, S.; Harris, R.; Arnaudo, G.; Mc Brearty, S. A strategic approach to social impact measurement of social enterprises. Soc. Enterp. J. 2009, 5, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, A.; Weber, C. Developing a conceptual framework for comparing social value creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A.; Rangan, V.K. What impact? Aframework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, K.; Lynch-Cerullo, K. Measuring the social returns of nonprofits and social enterprises: The promise and perils of the SROI. Nonprofit Policy Forum 2014, 5, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, C. Impact Assessment for Development Agencies: Learning to Value Change; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.; Lawlor, E.; Neitzert, E.; Goodspeee, T. A guide to Social Return on Investment; The SROI Network: Liverpool, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Foundation 101; Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume GRI101, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- GECES Sub-Group on Impact Measurement. Proposed Approaches to Social Impact Measurement in European Commission Legislation and in Practice Relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). About Integrated Reporting; International Integrated Reporting Council: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Furlotti, K. The materiality assessment and stakeholder engagement: A content analysis of sustainability reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puroila, J.; Mäkelä, H. Matter of opinion Exploring the socio-political nature of materiality disclosures in sustainability reporting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 1043–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Guix, M.; Bonilla-Priego, M.J. Corporate social responsibility in cruising: Using materiality analysis to create shared value. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, G. The quality of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting: Empirical evidence and critical points. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmini, L.; Bavagnoli, F.; Comoli, M.; Riva, P. Waiting for materiality in the context of integrated reporting: Theoretical challenges and preliminary empirical findings. In Sustainability Disclosure: State of the Art and New Directions; Emerlad: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 135–163. ISBN 1479351220150. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate sustainability: First evidence on materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. Stakeholder engagement and corporate social responsibility reporting: The ownership structure effect. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder relationships, engagement, and sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A method for making it work in practice. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, J. Prioritizing sustainability indicators: Using materiality analysis to guide sustainability assessment and strategy. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, L.C.; Searcy, C. An analysis of indicators disclosed in corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, D.W. Comparative power of student T test and Mann-Whitney U test for unequal sample sizes and variances. J. Exp. Educ. 1987, 55, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachar, N. The Mann-Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2008, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B.; Grove, D. Use of the Mann-Whitney U-test for clustered data. Stat. Med. 1999, 18, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawilowsky, S.; Fahoome, G. Kruskal-Wallis test: Basic. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wolniak, R.; Hąbek, P. Quality assessment of CSR reports—Factor analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 220, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Martell, T.F.; Demir, M. An evaluation of the quality of corporate social responsibility reports by some of the world’s largest financial institutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyskens, M.; Paul, K. The evolution of corporate social reporting practices in Mexico. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Dehon, C. Influence functions of the Spearman and Kendall correlation measures. Stat. Methods Appl. 2010, 19, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Anbumozhi, V. Determinant factors of corporate environmental information disclosure: An empirical study of Chinese listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]