We Learnt a Lot: Challenges and Learning Experiences in a Southern African—North European Municipal Partnership on Education for Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Study in a Broad Context

1.2. Framework and Organisations Involved

- (1)

- re-orient education towards sustainable development,

- (2)

- increase access to quality education,

- (3)

- deliver trainers’ training programmes and to develop methodologies and learning materials for them,

- (4)

- lead advocacy and awareness-raising efforts.

1.3. The Purpose of the Work and its Significance

- ➢

- What kind of challenges did the project team face and how were they solved as the project plan was implemented?

- ➢

- How did the participants in the project team express their learning outcomes from being a part of the partnership?

- ➢

- What can South and North learn from one another through a partnership?

1.4. Municipal Partnerships as a Framework for Learning

1.5. Critical Knowledge Capabilities

1.6. Outline of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of Study

2.2. Data Collection and Data Analysis

- (1)

- experiences and approaches to challenges,

- (2)

- learning from solving the challenges,

- (3)

- outcomes from implementation of the project plan.

2.3. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Category A. Understanding

3.1.1. The Project

- ➢

- to understand that you can’t make changes in the plan, not change the numbers of seminars, not change an activity to something else. You have to follow the plan...

- ➢

- as knowing how to spend the budget was not clear, not how to worry about it.

- ➢

- some difficulties to get new people on board … to engage.

- ➢

- My biggest challenge was to know what I was supposed to do in the project.

- ➢

- I’m still a bit confused.

- ➢

- Why am I involved, I would like to understand.

- ➢

- The project plan is unclear on what is to be done in the schools involved.

- ➢

- It was unclear to me who is involved and their roles. Is the teacher we meet part of the project or not? I find it difficult to invest wholeheartedly on partners if you do not know if it is long-term.

- ➢

- … easier to evaluate the number of things in a quantitative way. More difficult to evaluate the quality of activities.

- ➢

- There was no knowledge about the curriculum in the municipality.

3.1.2. Cultural Issues and South-North Collaboration

- ➢

- To understand each other. This is important, and makes it possible for us to carry out the project.

- ➢

- It was a shock to come here. I was not prepared for the huge social differences … I need to understand why we are here? Why are we collaborating?

- ➢

- Unclear about the needs, how we as swedes can contribute to the Namibian part of the project. They have to do it in their way, in their context, even though ESD is new to them. Our role and expectations of us are unclear.

- ➢

- …to create and develop something out of our collaboration… to consist in a longer run. Place the project in a bigger perspective. What are we leaving after the project? What would we like to save for the future?

- ➢

- It is a bit presumptuous to think that the collaboration and the project should be able to make a huge difference, but it may help to start something.

3.1.3. Education for Sustainable Development

- ➢

- We do have different entrances and understandings of the concepts as we are living and working in quite different contexts, Sweden and Namibia. What are we talking about when we are discussing ESD? To some extent, different issues in sustainability are important to us.”. “Some are beginners and some have worked with ESD for a long time.

- ➢

- …when I came on board… I didn’t have a clear concept. I didn’t really have an understanding of ESD...

3.2. Category B. Implementation

- ➢

- We met municipal officials at a higher level, not on the operational level, so nothing happened. That was a challenge, we became impatient …

3.2.1. Teamwork, Project Activities and Communication

- ➢

- To get people on board … to make them find time and engagement … especially as they were not used to working in this kind of project collaboration.

- ➢

- … develop ESD seminars and learn together, not one partner telling the other exactly how to do things, but to inspire, discuss and decide together.

- ➢

- To me as a teacher, the ESD project is something extra.

- ➢

- One of our team members was pushing very much for the project to be a success; it was just to make it done…

- ➢

- We try to give service to our school colleagues.

- ➢

- I feel support … It was just that the venue, the seminars were so far away from my school. The transport issue was an issue – to transport materials from my school to the municipality building.

- ➢

- My commitment to the project is often limited by work priority. As I am working for a Government school, the ESD project has been like an extra more activity. It is not part of formal education. It is something extra I do in my spare time, after school.

- ➢

- It’s worth it! We learn a lot.

- ➢

- The communication between meetings is weak, both local and between the two cities. Everyone has other things to focus on.

- ➢

- Back at home, I feel quite lonely while running this project as I am not meeting other project members daily, no exchange in the corridors so to say.

3.2.2. School Collaboration

- ➢

- A challenge might be to weave together our curriculums so we can do the same activities in both municipalities.

- ➢

- … more fact-based and name on species in Namibia, … more focus on diversity and variation among marine organisms in Sweden.

- ➢

- … the communication failed… resulting in disappointed learners and teachers in both cities.

- ➢

- You have to be very clear about things, to really have an agreement about things. It’s frustrating when things don’t work because you have not agreed on who is the responsible person.

3.3. Category C: Gaining Insights

3.3.1. Project Plan, Teamwork and Processes

- ➢

- After many, many, emails and discussions, the understanding of the project plan and how to run the project has developed.

- ➢

- Now, there is an understanding of the function of the project plan. It’s a ‘ripening process’.

- ➢

- Sometimes you need to be more than clear, even more clear than you thought you have to.

- ➢

- The project leader explained to me. She taught me how the budget works … Then it was clear.

- ➢

- There is a strict control … limitation of unnecessary expenses … no challenges with the budget today.

- ➢

- The difference between this and many other South-North projects is that we are not coming telling them how to do things … that is something I think is highly appreciated. Things must be done on the basis of the conditions in each municipality.

- ➢

- The project is based on committed people. It would not be possible without these.

- ➢

- When you work with people, a learning lesson is that one should be responsive and humble. You can’t place yourself higher than anyone else. Hierarchy can be very troublesome. The difference in culture is exciting, but sometimes difficult to relate to.

3.3.2. Communication and Sharing

- ➢

- The projects meetings, twice a year are important. This is when we sum up … reflect on the implementation, outcomes and planning for the next activity in the project plan.

- ➢

- Clarity in communication is even more important than I thought before being involved in this project… to discuss and explain … over and over again.

- ➢

- We learned from running the project, the content, but also from the challenges, between different people and organisations, different cultures.

- ➢

- We share examples, possibilities, different activities and ways of ESD. I believe it starts processes, thoughts in the project team.

- ➢

- We are more experienced now.

3.3.3. Implementation of Activities

- ➢

- We need knowledge to make good discussions, to be able to reflect, argue and develop action competence.

- ➢

- Meeting people from other organisations … is also generating new thoughts and ideas, on things to develop and different ways of doing things.

- ➢

- When you leave your ‘black box’ and reflect, you learn new ways of thinking and doing things.

- ➢

- … very helpful to me, is that when you have a presenter, you can share the workshop sheets with them. … they can add in questions that will address the aims of the specific workshop… so people will be able to listen. They talk about something relevant, so it’s going to address people. That has been very helpful.

- ➢

- Since we have the RCE, we have very good cooperation.

3.4. Category D: Knowledge Formation

3.4.1. Sharing and Learning Together

- ➢

- I learned to work with people. Most of the time I used to work on myself … but now working in a team, it is really great.

- ➢

- An understanding of different cultures, in the organisations and countries, different working methods, our different hierarchy cultures that also come into play.

- ➢

- It is now an exchange of knowledge.

- ➢

- We learn from the challenges, from our solutions.

- ➢

- … most funds would like to have measurable results, the soft values are ‘a bit flimsy’. Cultural understanding is difficult to measure, but the ‘soft ware’ makes sense … might be the most important after a while.

3.4.2. Learning by Activities

- ➢

- Practical work, it makes things practical… makes you understand easier…

- ➢

- …but you still use the same concept as in the ESD project.

- ➢

- Sometimes we think that we can’t learn from children, but doing this, workshops with adults, we actually learn from the kids, and that was very interesting. It’s very good for myself, motivates me to keep on doing this. Rather I let the kids have hands-on experiences, they seem to remember it.

3.4.3. Local Anchoring of the Global

- ➢

- Going to Sweden was the most wonderful thing in this project. It brought me considerable experience. It was a good experience. My way of thinking is very different now.

- ➢

- We are contributing and we can learn from our partners, it’s really an exchange of knowledge.

- ➢

- … you have to remember, changes take time.

3.5. Category E: Capacity for the Future

- ➢

- This kind of project is always an investment for the future.

- ➢

- We have developed our thoughts, received new ideas and insights, developed networks, a lot of processes have started, and this might sustain in the long run.

3.5.1. Professional Knowledge and Experience

- ➢

- What I learned from this project will definitely be useful for me in the future.

- ➢

- We learn things and bring the knowledge back to our organisations, in ordinary work. The things you learn… and the various experiences, you bring them with you in your further career. You learn about different ways of thinking, methods, how to run and develop a project, and how to develop new ideas.

- ➢

- The main outcome for me is my development of how to run a project. It helps me to organise myself, in my job and in private. From this … I learned about time management. It’s important.

3.5.2. Rethinking Education

- ➢

- The work we are doing now… developing the competence and knowledge of teachers is for the future.

- ➢

- … they have the possibility to try another way of education, to do it in another way, more exploratory and student-centred working methods.

- ➢

- All these examples… I am sure, or at least I believe, that the seminars have started a process in Swakopmund.

- ➢

- The schools have started to move outside the classroom with the learners, with the kids, and that includes also the marine life, as well as raising the awareness of our environment.

- ➢

- … the driving force, a teacher, used to be a ‘normal teacher’… now a dedicated teacher for special projects, which is beneficial to our project.

- ➢

- We try to coordinate projects of environmental clubs, so we think by using the ESD workshops that we got. Workshops are going to be included in one of our new projects, the green project, so every workshop that we did before, energy, waste etc., we will do again.

3.5.3. Networks

- ➢

- This kind of project will always facilitate future cooperation.

- ➢

- I think partnership with different stakeholders will stay.

- ➢

- The networks we are building among our organisations are also important for the future. It’s easier to contact and ask for help or collaboration when we know each other. That’s also a kind of result in this project.

- ➢

- For us as a municipality, the main thing is to be there, to support the schools and see that it continues. That’s our vision for the future. In terms of reaching the community, and the grassroots level, we have implemented the seminars to different schools, in different areas.

- ➢

- We have a commitment from the Ministry of Education, supporting us in our areas. They are willing to support us in our goals and objectives of the project…

- ➢

- Maybe, it will be closer to our goal, to proclaim Swakop as sustainable, the first sustainable town in Namibia.

3.5.4. South-North Understanding

- ➢

- Both the harder and the softer issues, between people and cultures, we will bring with us.

- ➢

- We develop friendships and learn from each other. We became close friends just because of the project.

- ➢

- To participate, be part of this project will be useful to me … I have seen poverty and huge social differences among the population. Meeting people in real life is important! Without learning and sharing… there will be no changes.

- ➢

- To be involved in the project affects me a lot. I get a completely different, completely new picture of how things work in a poor country. I have a different understanding of the complexity of social-economic differences and injustices.

- ➢

- Cultural understanding is difficult to measure, but the ‘soft ware’ makes sense … might be the most important after a while.

- (1)

- Challenges experienced: category A and B

- (2)

- Solutions recognised: category C

- (3)

- Learning outcome: category D and E

4. Discussion

4.1. Different Types of Challenges the Project Team Faced

4.2. The Way the Project Team Found Solutions

4.3. The Project Team Participants’ Experiences of Learning Outcomes

4.4. What South and North Can Learn From One Another Through a Partnership

5. Conclusions: Deepened Understanding through Three Dimensions of Learning

5.1. Learning Dimension 1: Establishing Critical Knowledge Capabilities Enhancing Democratic Action

5.2. Learning Dimension 2: Transforming Knowledge Coherently

5.3. Learning Dimension 3: Developing Knowledge Formation and Capacity

5.4. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/globalpartnerships/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- SIDA. Available online: https://www.sida.se/English/partners/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy: ICLD. The Municipal Partnership Programme. Available online: https://icld.se/en/municipal-partnership/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy: ICLD. ICLD in the world. Available online: https://icld.se/en/where-we-work/icld-in-the-world/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Global RCE Network. Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.rcenetwork.org/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Devers, U.-K. Municipal partnerships and learning—Investigating a largely unexplored relationship. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Wilson, G. Learning and mutuality in municipal partnerships and beyond: A focus on northern partners. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.; Johnson, H. Knowledge, learning and practice in North–South practitioner-to-practitioner municipal partnerships. Local Gov. Stud. 2007, 33, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontenbal, M.C. Differences in learning practices and values in north-south city partnerships: Towards a broader understanding of mutuality. Public Admin. Dev. 2013, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.B.; Anderberg, S.; Coenen, L.; Neij, L. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phago, K.; Molosi-France, K. Reconfiguring local governance and community participation in South Africa and Botswana. Loc. Econ. 2018, 33, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, J.; Smedby, N.; McCormick, K. The Role of Local Governments in Governing Sustainable Consumption And Sharing Cities. In A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 172–184. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education: Preparing Learners for the Challenges of the 21st Century; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dasli, M. Reviving the ‘moments’: From cultural awareness and cross-cultural mediation to critical intercultural pedagogy. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 2011, 19, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Intercultural Competences: Conceptual and Operational Framework; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.; Byram, M.; Lázár, I.; Mompoint-Gaillard, P.; Philippou, S. Developing Intercultural Competence through Education; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Competency for an Inclusive World. Assessing what Education Systems and Teachers Can Do to Promote Global Competence; OECD Secretariat, Directorate for Education and Skills: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.; Wilson, G. North–South/South–North partnerships: Closing the ‘mutuality gap’. Public Admin. Dev. 2006, 26, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.F. Authentic NGDO Partnerships in the New Policy Agenda for International Aid: Dead End or Light Ahead? Dev. Chang. 1998, 29, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, U.; Limani, I. Intermunicipal collaboration—A smart alternative for small municipalities? Scand. J. Public Admin. 2015, 19, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Katajamäki, H.; Mariussen, Å. Transnational learning in local governance: Two lessons from Finland. In Learning Transnational Learning; Mariussen, Å., Virkkala, S., Eds.; Routledge Studies in Human Geography: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderberg, E.; Nordén, B.; Hansson, B. Global learning for sustainable development in higher education: Recent trends and critique. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 2009, 10, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, M.J.; Schroeder, K. International adult education partnerships: Much more than a one way street. Adult Educ. Dev. 2007, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Competences for Democratic Culture: Living Together as Equals in Culturally Diverse Democratic Societies; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, A.M. Scientific Literacy and Informal Learning. Studies Sci. Educ. 1983, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J. Doing justice to the informal science education community. Studies Sci. Educ. 2010, 50, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordén, B. Learning and Teaching Sustainable Development in Global-Local Contexts. Ph.D. Thesis, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- King, H.; Dillon, J. Learning in informal settings. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Seel, N., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1905–1908. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle, N. Teaching for Understanding at University: Deep Approaches and Distinctive Ways of Thinking; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J.B. Approaches to learning in secondary and tertiary students in Hong Kong: Some comparative studies. Educ. Research J. 1991, 6, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schugurensky, D. The Forms of Informal Learning: Towards a Conceptualization of the Field. NALL Working Paper #19. 2000. Available online: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/2733/2/19formsofinformal.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Molosi, K.; Dipholo, K.B. Power relations and the paradox of community participation among the San in Khwee and Sehunong. J. Public Admin. Dev. Altern. 2016, 1, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organisational Learning II. Theory, Method and Practice; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, J.A.; Marton, F. The University of Learning: Beyond Quality and Competence; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nordén, B.; Anderberg, E. Knowledge capabilities for sustainable development in global classrooms–local challenges. J. Didact. Educ. Policy 2011, 20, 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T. Moving toward the centre: Transformative learning, global learning, and indigenization. J. Transform. Learn. 2020, 7, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Högfeldt, A.-K.; Rosén, A.; Mwase, C.; Lantz, A.; Gumaelius, L.; Shayo, E.; Lujara, S.; Mvungi, N. Mutual Capacity Building through North-South Collaboration using Challenge Driven Education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mula, I.; Tilbury, D.; Ryan, A.; Mader, M.; Dlouha, J.; Mader, C. Catalysing Change for Higher Education for Sustainable Development: A review of professional development initiatives. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 2017, 18, 798–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, S. The need for a complexity informed active citizenship education program. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2019, 59, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S. A ladder of citizen participation. AIP J. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

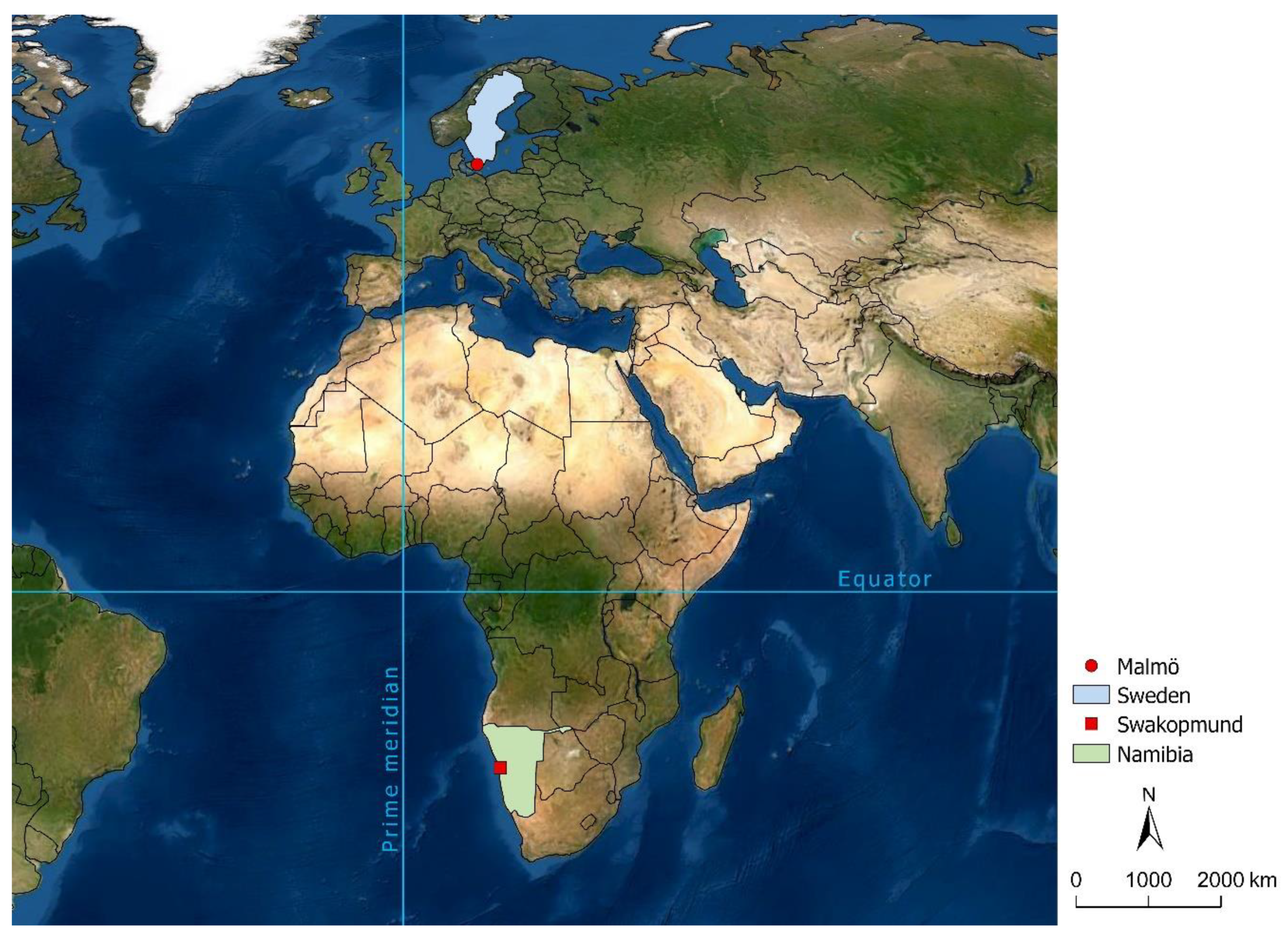

- The Country Guide (Landguiden, in Swedish). Available online: www.ui.se (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Natural Earth. Available online: https://www.naturalearthdata.com/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Esri. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/home (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; p. 201. ISBN 978-0-19-968945-3. [Google Scholar]

- Theman, J. Uppfattningar om Politisk Makt. [Conceptions of Political Power]. Ph.D. Thesis, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Marton, F.; Booth, S. Learning and Awareness; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L. Research Methods’ analytical and contextual qualities. In Perspectives on Qualitative Method; Allwood, C.M., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2004; pp. 65–95. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, S. Learning Computer Science and Engineering in Context. Comp. Sci. Educ. 2001, 11, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Research Council. Good Research Practice. Stockholm, Sweden. 2017. Available online: https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Bowden, J.A. Capabilities–driven curriculum design. In Effective Learning and Teaching in Engineering; Baillie, C., Moore, I., Eds.; RoutledgeFalmer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Kieft, G. Education for Sustaianble Development. Research Overview; Review 2010:13; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA): Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson, P.; Harvey, B.; Van Epp, M.; Thornton, P.K. Social learning and sustainable development. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Main Category | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| A | Understanding | The project |

| Cultural issues and South-North collaboration | ||

| Education for sustainable development | ||

| B | Implementation | Project activities and communication |

| School cooperation | ||

| C | Gaining insights | Project plan, teamwork and processes |

| Communication and sharing | ||

| Implementation of activities | ||

| D | Knowledge formation | Sharing and learning together |

| Learning by activities | ||

| Local anchoring of the global | ||

| E | Capacity for the future | Professional knowledge and experiences |

| Rethinking education | ||

| Networks | ||

| South-North understanding |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonesson, K.; Nordén, B. We Learnt a Lot: Challenges and Learning Experiences in a Southern African—North European Municipal Partnership on Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208607

Sonesson K, Nordén B. We Learnt a Lot: Challenges and Learning Experiences in a Southern African—North European Municipal Partnership on Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208607

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonesson, Kerstin, and Birgitta Nordén. 2020. "We Learnt a Lot: Challenges and Learning Experiences in a Southern African—North European Municipal Partnership on Education for Sustainable Development" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208607

APA StyleSonesson, K., & Nordén, B. (2020). We Learnt a Lot: Challenges and Learning Experiences in a Southern African—North European Municipal Partnership on Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 12(20), 8607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208607