Global Learning for Sustainable Development: A Historical Review

Abstract

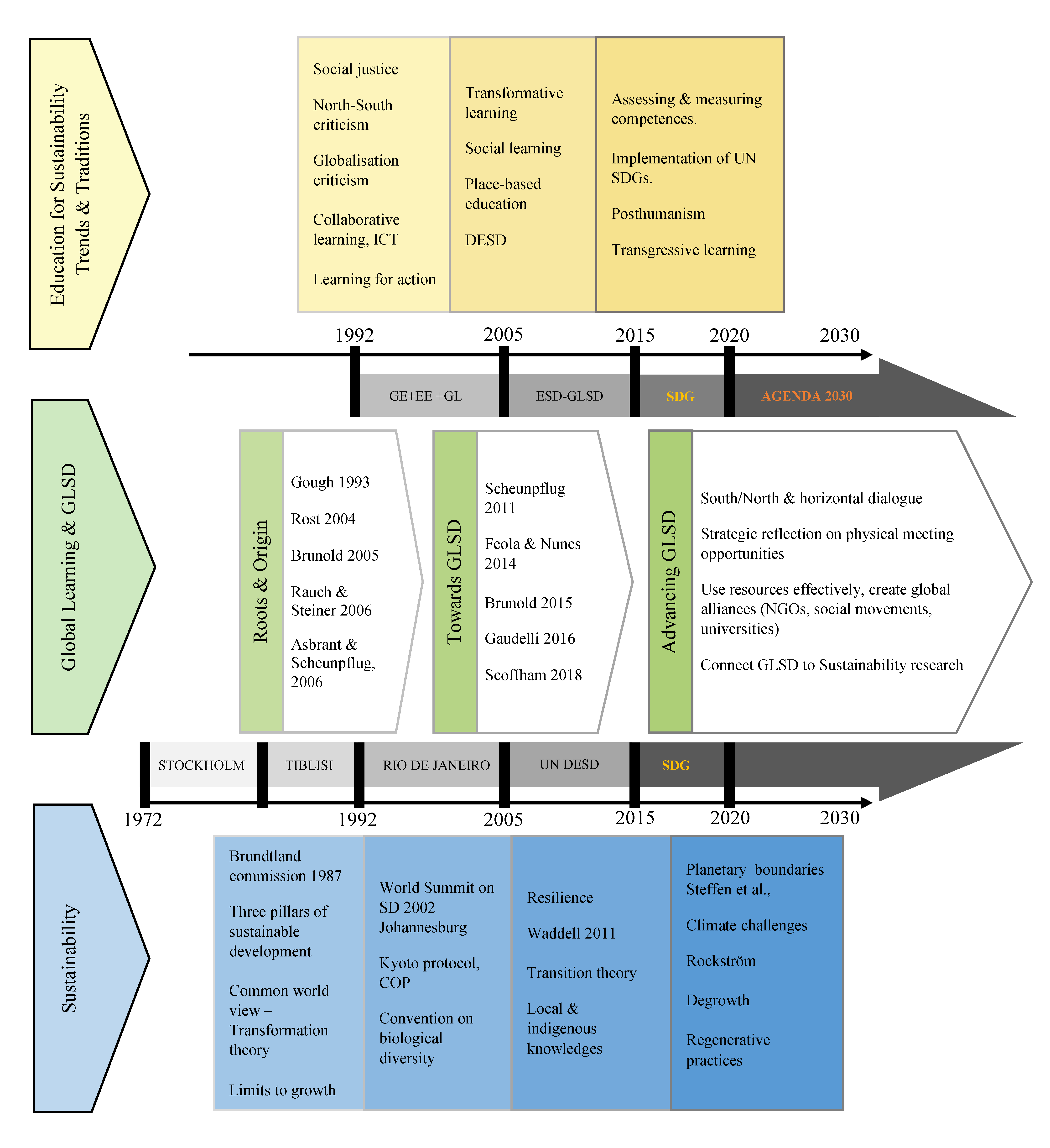

1. Historical Background of the Field—Agenda 21 and Learning for Sustainable Development

2. Global Learning for Sustainable Development

3. Aim

4. Reviews of ESD Literature

5. Method

5.1. Choice of Search Terms

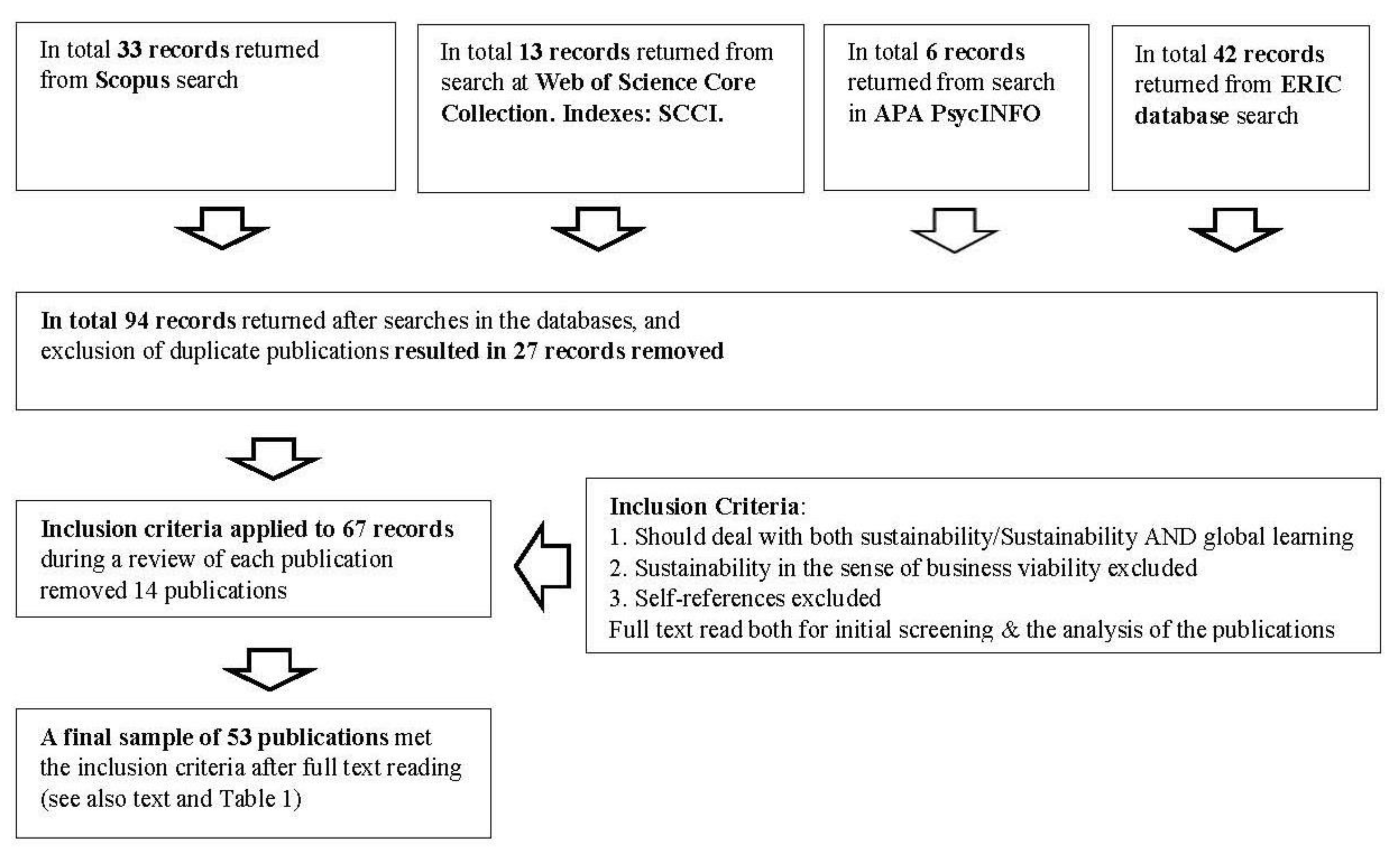

5.2. Search and Screening

6. Thematic Analysis of Reviewed Publications

6.1. General and Historical Overviews

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Policy Research

6.4. Research on Formal Primary and Secondary Education Contexts

6.5. Research in Further and Higher Education Contexts

6.6. Social Learning and Learning Outside Formal Education Contexts

6.7. North–South Relationships

7. GLSD against the Background of Debates and Trends in ESD

“…understand and critically reflect global interdependencies, own values and attitudes, develop own positions and perspectives, see options, capability to make choices, to participate in communication and decisions within a global context.”[99] (pp. 33–34)

8. Limitations of Strategies Implemented Since Rio

9. Where Do We Go from Here?

10. Conclusions

11. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. Resolutions Adopted by the Conference. A/CONF.151/26/Rev.l. In Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1993; Volume I, Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/dsd/agenda21/Agenda%2021.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Agenda 21. United Nations Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Brundtland, G. Our Common Future (The Brundtland Report). In World Commission on environment and Development; University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aikens, K.; McKenzie, M.; Vaughter, P. Environmental and sustainability education policy research: A systematic review of methodological and thematic trends. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetz, J.M.; Walid, M. Social Responsibility Versus Sustainable Development in United Nations Policy Documents: A Meta-analytical Review of Key Terms in Human Development Reports. In Social Responsibility and Sustainability; World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 301–334. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B.; Wals, A.E.J. Globalization and environmental education: Looking beyond sustainable development. J. Curric. Stud. 2008, 40, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.; Kieft, G. Education for Sustainable Development: Research Overview; Sida Review 2010: 13; Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

- Gaudelli, W. World Class: Teaching and Learning in Global Times; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.A. Typology of Corporate Environmental Policies. Environ. Ethics 1998, 20, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schugurensky, D. The forms of informal learning: Towards a conceptualization of the field. SSHRC Research Network New Approaches to Lifelong Learning (NALL) Wall Working Paper No.19. 2000. Available online: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/2733/2/19formsofinformal.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Rauch, F.; Steiner, R. School development through Education for Sustainable Development in Austria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentall, C.; Bourn, D.; McGough, H.; Hodgson, A.; Spours, K. Global Learning for Global Colleges: Creating opportunities for greater access to international learning for 16–25 year olds. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2014, 38, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scheunpflug, A.; Asbrand, B. Global education and education for sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, Z.; Yeates, N.; Young, P. What Can Global Perspectives Contribute to Curriculum Development in Social Policy? Soc. Policy Soc. 2005, 4, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T. Moving toward the centre: Transformative learning, global learning, and indigenization. J. Transform. Learn. 2020, 7, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grosseck, G.; Țîru, L.G.; Bran, R.A. Education for sustainable development: Evolution and perspectives: A bibliometric review of research, 1992–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascopé, M.; Perasso, P.; Reiss, K. Systematic Review of Education for Sustainable Development at an Early Stage: Cornerstones and Pedagogical Approaches for Teacher Professional Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Nguyen, V.-T. Mapping the Landscape and Structure of Research on Education for Sustainable Development: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Chatpinyakoop, C. A Bibliometric Review of Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development, 1998–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Links between the Global Initiatives in Education, Education for Sustainable Development in Action, Technical Paper No. 1. September 2005. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000140848?posInSet=1&queryId=28606f6d-799c-4d08-ab2b-3e2cf223a5da (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudelli, W. Global Citizenship Education: Everyday Transcendence; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, A.; Warwick, P. Global Learning and Education: Key Concepts and Effective Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brunold, A.O. The United Nations decade of education for sustainable development, its consequences for international political education, and the concept of global learning. Int. Educ. J. 2006, 7, 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brunold, A.O. Global learning and education for sustainable development. High. Educ. Eur. 2005, 30, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunold, A.O. Civic Education for Sustainable Development and its Consequences for German Civic Education Didactics and Curricula of Higher Education. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2015, 6, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brunold, A.O. Globales Lernen und Lokale Agenda 21. Aspekte kommunaler Bildungsprozesse in der “Einen Welt”; Global Learning and Local Agenda 21. Aspects of Communal and Educational Processes in “One World”; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.-K. Play locally, learn globally: Group selection and structural basis of cooperation. J. Bioeconomics 2008, 10, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazem, D. Critical Realist Approaches to Global Learning: A Focus on Education for Sustainability. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 10, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunpflug, A.; Krogull, S.; Franz, J. Understanding Learning in World Society: Qualitative Reconstructive Research in Global Learning and Learning for Sustainability. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2016, 7, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, S.-M. Sustainable Knowledge Transformation in and through Higher Education: A Case for Transdisciplinary Leadership. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2017, 8, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.W. Information Technology and Global Learning for Sustainable Development: Promise and Problems. Altern. Glob. LocalPolitical 1994, 19, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang-Wojtasik, G. Transformative Cosmopolitan Education and Gandhi’s Relevance Today. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 10, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatley, J. Universal Values as a Barrier to the Effectiveness of Global Citizenship Education: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2019, 11, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, E. No global citizenship? Re-envisioning global citizenship education in times of growing nationalism. High Sch. J. 2017, 100, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoffham, S. Global Learning: A Catalyst for Curriculum Change. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.G.; Park, I. A review of the differences between ESD and GCED in SDGs: Focusing on the concepts of global citizenship education. J. Int. Coop. Educ. 2016, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bourn, D. Education for sustainable development and global citizenship. The challenge of the UN-decade. Zep Z. Für Int. Bild. Und Entwickl. 2005, 28, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. Globalization, Education, and Citizenship: Solidarity vs Markets. In Globalization and Education, Collected Essays on Class, Race, Gender, and the State; Torres, C.A., Ed.; Teacher’s College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andreotti, V. Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy Pract. A Dev. Educ. Rev. 2006, 3, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education, Topics and Learning Objectives; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-92-3-100102-4. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232993 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Vaccari, V.; Gardinier, M.P. Toward One World or Many? A Comparative Analysis of OECD and UNESCO Global Education Policy Documents. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2019, 1, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaomin, L.; Auld, E. A historical perspective on the OECD’s ‘humanitarian turn’: PISA for Development and the Learning Framework 2030. Comp. Educ. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva, Z.; Mochizuki, Y. Regional Centres of Expertise: Innovative Networking for Education for Sustainable Development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 2, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendix, B. Decolonizing Development Education Policy: The Case of Germany. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 2, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzifotiou, A. Education for sustainable development: Vision, policy, practices—An open or closed ‘doorway’ for teachers and schools? World Sustain. Ser. 2018, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J. Becoming Critical: A Challenge for the Global Learning Programme? Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2017, 3, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell-Straub, S. Mathematics Education Meets Development Education: The Competency ‘Mathematical Modelling’ Combined with Global Skills and Competencies in a Secondary School Project in Germany. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2013, 1, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béneker, T.; van Dis, H.; van Middelkoop, D. World-Mindedness of Students and Their Geography Education at International (IB-DP) and Regular Schools in the Netherlands. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2014, 6, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguth, B.M.; Yang, H. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as a Global Content Framework? J. Int. Soc. Stud. 2019, 1, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bangay, C. Protecting the Future: The Role of School Education in Sustainable Development--An Indian Case Study. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2016, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, S.J. Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship: Leadership, Collaboration, and Networking in Primary Schools. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2015, 1, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewchurran, K.; McDonogh, J. The Phenomenon of “Being-In-Management” in Executive Education Programmes: An Integrative View. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2015, 7, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Camacho, M.T.; Graell-Martín, M.; Fuentes-Loss, M.; Balaguer-Fàbregas, M.C. Integrating sustainability into higher education curricula through the project method, a global learning strategy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickford, T.; Ellis, L. The creation of interactive activity pods at a Recycling Education Centre. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, A.; Hawkins, G. Global Learning and Development as an Engagement Strategy for Christian Higher Education: A Macro Study. High. Educ. 2016, 5, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, S.E. Global Citizenship as a Floating Signifier: Lessons from UK Universities. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2014, 6, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S. Sustainable distance learning for a sustainable world. J. Open Distance Learn. 2016, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waddell, S. Global Action Networks: Creating our Future Together; Palgrave-Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell, S.; McLachlan, M.; Dentoni, D. Learning & transformative networks to address wicked problems: A golden invitation. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Feola, G.; Nunes, R. Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the transition movement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naleppa, M.J.; Waldbillig, A.A. International staff exchange: Evaluation of a collaborative learning partnership. Int. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balls, E. Analysing Key Debates in Education and Sustainable Development in Relation to ESD Practice in Viet Nam. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2016, 1, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M.; Laitinen, J. The Earth Charter Goes Interactive and Live with e-GLO: Using New Media to Train Youth Leaders in Sustainability on Both Sides of the Digital Divide. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 4, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J. Global Learning from the Periphery: An Ethnographic Study of a Chinese Urban Migrant School. Sustainability 2020, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrey, M. CLICK: Arts Education and Critical Social Dialogue within Global Youth Work Practice. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2015, 1, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithead, J.; Humble, S. How Children Living in Poor Informal Settlements in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana, Perceive Global Citizenship. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2020, 12, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.; Ho, L.-C.; Kiwan, D.; Peck, C.L.; Peterson, A.; Sant, E.; Waghid, Y. (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reysen, S.; Katzarska-Miller, I. A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriprakash, A.; Tikly, L.; Walker, S. The erasures of racism in education and international development: Re-reading the ‘global learning crisis’. Compare 2020, 50, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-M.; Hong, S.-K. Island development: Local governance under globalization. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2014, 3, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, D. A review of clean energy innovation and technology transfer in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riitaoja, A.-L.; Posi-Ahokas, H.; Janhonen-Abruquah, H. North-South-South Collaboration as a Context for Collaborative Learning and Thinking with Alternative Knowledges. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2019, 2, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heto, P.P.-K.; Odari, M.H.; Sunu, W.K. Different schools, different cultures. In Handbook on Promoting Social Justice in Education; Papa, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 583–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. The case for inclusion of international planning studios in contemporary urban planning pedagogy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, C.; Salam, I. Making a MEAL out of a Global Professional Learning Community: A Transformative Approach to Global Education. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2014, 3, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.; Webb, G. A review of the literature to inform the development of a new model of global placement: The Global Learning Partnership. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2018, 23, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikos, L.H.; Manning, S.B.; Frieders, Z.J. Ready or not here I come: A qualitative investigation of students’ readiness perceptions for study abroad/away. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2019, 8, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diprose, K. Critical distance: Doing development education through international volunteering. AREA 2012, 44, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L. Global citizenship, global health, and the internationalization of curriculum: A study of transformative potential. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2010, 14, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabtree, R.D. Mutual empowerment in cross-cultural participatory development and service learning: Lessons in communication and social justice from projects in El Salvador and Nicaragua. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1998, 26, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie Smith, M.; Laurie, N. International volunteering and development: Global citizenship and neoliberal professionalisation today. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinert, L.; Guffler, K.; Polak, J.T. International Development Volunteering: An Instrument for Promoting Education in Line with the Sustainable Development Goals? Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2019, 1, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D.; Coles, R. The new environmentalism of everyday life: Sustainability, material flows and movements. Contemp. Political Theory 2016, 15, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, A. Working with/in/against more-than-human environmental sustainability education. Educ. J. Res. Debate 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cielemęcka, O.; Daigle, C. Posthuman sustainability: An ethos for our anthropocenic future. TheoryCult. Soc. 2019, 36, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromquist, N.P.; Monkman, K. Globalization and Education: Integration and Contestation across Cultures; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eilks, I.; Hofstein, A. Combining the question of the relevance of science education with the idea of education for sustainable development. In Science Education Research and Education for Sustainable Development; Eilks, I., Markic, S., Ralle, B., Eds.; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, K.; Hopkins, C.A. ESD for All: Learnings from the Indigenous ESD Global Research. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2019, 21, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Jeronen, E.; Lemmetty, P. Teaching and learning methods in geography promoting sustainability. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VENRO. “Globales Lernen” als Aufgabe und Handlungsfeld Entwicklungspolitischer NichtRegierungsorganisationen; Grundsatze, Probleme und Perspektiven der Bildungsarbeit des VENRO und seiner Mitgliedsorganisationen; VENRO: Bonn, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scheunflug, A. How to get Knowledge into Competences?–Challenges for Global Learning in Schools. In Proceedings of the Keynote 1: Professor Dr Annette Scheunpflug, Bamberg University, at the Conference by Globala Skolan, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 19 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yueh, M.-C.M.; Barker, M. Framework Thinking, Subject Thinking and ’Taiwanness´ in Environmental Education. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2011, 27, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourn, D. Global Learning and Subject Knowledge. Development Education Research Centre Research Paper No. 4; University College London, Institute of Education: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1476665/1/GlobalLearningAndSubjectKnowledge.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Bowden, J.A. Capabilities–driven curriculum design. In Effective Learning and Teaching in Engineering; Baillie, C., Moore, I., Eds.; RoutledgeFalmer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth, S.; Thomas, I. Competencies or capabilities in the Australian higher education landscape and its implications for the development and delivery of sustainability education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunpflug, A. Global education and cross-cultural learning: A challenge for a research-based approach to international teacher education. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2011, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, F. The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourse of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A.; Bonal, X.; Zancajo, A. Indicators for a Broad and Bold Post-2015 Agenda: A Comprehensive Approach to Educational Development. Globalization, Education and Social Policies (GEPS); Open Society Foundations, Autonomous University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazey, I.; Schäpke, N.; Caniglia, G.; Patterson, J.; Hultman, J.; Van Mierlo, B.; Säwe, F.; Wiek, A.; Wittmayer, J.; Al Waer, H.; et al. Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J. An Analysis of New Labour’s Policy on Education for Sustainable Development with Particular Reference to Socially Critical Approaches. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, J. Competencies for education for sustainability. Dev. Educ. J. 2004, 11, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Agenda 2030, Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- SDG Indicators. SDG Indicators—SDG Indicators (un.org). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database/ (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Hunt, F. Global Learning in Primary Schools in England: Practices and Impacts; Development Education Research Centre. Research Paper No. 9; Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gwin, R.; Foggin, J.M. Badging for Sustainable Development: Applying EdTech Micro-Credentials for Advancing SDGs amongst Mountain and Pastoralist Societies. Preprints 2020, 2020030402. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202003.0402/v1 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Thakur, R. The United Nations and the North-South Partnership: Connecting the Past to the Future. Ethics Int. Aff. 2020, 34, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsmark, C.N. Inspiring climate action without inducing climate despair. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e169–e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.; Leung, A. Illuminate: A Simulation Game to Instill Grounded Hope in Youth for Climate Action. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Folke, C. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J. Big World, Small Planet: Abundance within Planetary Boundaries; Max Ström: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lade, S.J.; Steffen, W.; De Vries, W.; Carpenter, S.R.; Donges, J.F.; Gerten, D.; Hoff, H.; Newbold, T.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J. Human impacts on planetary boundaries amplified by Earth system interactions. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Global Biodiversity Outlook 5; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; ISBN 9789292256883. Available online: www.cbd.int/GBO5 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Mir, W. Financing the United Nations Secretariat: Resolving the UN’s Liquidity Crisis; International Peace Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Bernstein, M.J.; Laubichler, M.; Caniglia, G.; Minteer, B.; Lang, D.J. A global classroom for international sustainability education. Creat. Educ. 2013, 4, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheunpflug, A. Global Learning: Educational research in an emerging field. Key Note at ECER 2019. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Schottenfeld, M.A. Internationalising experiential learning for sustainable development education. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, W.F.; Habron, G.B.; Johnson, H.L.; Goralnik, L. Critical thinking assessment across four sustainability-related experiential learning settings. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 38, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Situation Prospects. Statistical Annex; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. United Nations Millennium Declaration: Resolution 55/2. 2000. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_55_2.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Kuntsman, A.; Rattle, I. Towards a paradigmatic shift in sustainability studies: A systematic review of peer reviewed literature and future agenda setting to consider environmental (Un) sustainability of digital communication. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, A.G. Globalizing environmental education: What’s language got to do with it? J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 16, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Fünfschilling, L.; et al. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, R.E. The dominance of English in the international scientific periodical literature and the future of language use in science. Aila Rev. 2007, 20, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Q.; Liu, C.; Du, D. Globalization of science and international scientific collaboration: A network perspective. Geoforum 2019, 105, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANGEL. Global Education Digest 2020; Development Education Research Centre, UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10112144/1/Digest%202020%20Online.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2020).

| Year of Publication | Article Title | Authors | Searched Keywords A and/or B/Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | The erasures of racism in education and international development: re-reading the ‘global learning crisis’. | Sriprakash, A., Tikly, L., Walker, S. | A/Scopus + B/SSCI + ERIC |

| 2020 | A historical perspective on the OECD’s ‘humanitarian turn’: PISA for Development and the Learning Framework 2030. | Xiaomin, L., Auld, E. | A/Scopus + B/SSCI |

| 2020 | Global Learning from the Periphery: An Ethnographic Study of a Chinese Urban Migrant School. | Dong, J. | AB/SSCI |

| 2020 | Different schools, different cultures. | Heto, P.P.-K., Odari, M.H., Sunu, W.K. | A/Scopus |

| 2020 | How Children Living in Poor Informal Settlements in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana, Perceive Global Citizenship. | Leithead, J., Humble, S. | A/ERIC |

| 2019 | The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as a Global Content Framework? | Maguth, B.M.; Yang, H. | B/ERIC |

| 2019 | Universal Values as a Barrier to the Effectiveness of Global Citizenship Education: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis. | Hatley, J. | AB/ERIC |

| 2019 | Socio-Scientific Inquiry-Based Learning: An Approach for Engaging with the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals through School Science. | Amos, R., Levinson, R. | B/ERIC |

| 2019 | International Development Volunteering: An Instrument for Promoting Education in Line with the Sustainable Development Goals? | Scheinert, L., Guffler, K., Polak, J.T. | B/ERIC |

| 2019 | Toward One World or Many? A Comparative Analysis of OECD and UNESCO Global Education Policy Documents. | Vaccari, V. Gardinier, M.P. | B/ERIC |

| 2019 | North-South-South Collaboration as a Context for Collaborative Learning and Thinking with Alternative Knowledges. | Riitaoja, A.-L., Posi-Ahokas, H., Janhonen-Abruquah, H. | B/ERIC |

| 2019 | The case for inclusion of international planning studios in contemporary urban planning pedagogy. | Jones, P. | A/Scopus + B/SSCI |

| 2019 | Integrating sustainability into higher education curricula through the project method, a global learning strategy. | Fuertes-Camacho, M.T., Graell-Martín, M., Fuentes-Loss, M., Balaguer-Fàbregas, M.C. | AB/Scopus + AB/SSCI |

| 2019 | Ready or not here I come: A qualitative investigation of students’ readiness perceptions for study abroad/away. | Bikos, L.H., Manning, S.B., Frieders, Z.J. | B/PsycInfo |

| 2018 | International staff exchange: Evaluation of a collaborative learning partnership. | Naleppa, M.J., Waldbillig, A.A. | B/Scopus + A/SSCI |

| 2018 | Intercultural education as a prerequisite for sustainability. | Schrüfer, G., Schwarze, S., Obermaier, G. | AB/Scopus |

| 2018 | A review of the literature to inform the development of a new model of global placement: The Global Learning Partnership | Lees, J., Webb, G. | A/Scopus |

| 2018 | Education for sustainable development: Vision, policy, practices—an open or closed ‘doorway’ for teachers and schools? | Chatzifotiou, A. | AB/Scopus |

| 2018 | Global Learning: A Catalyst for Curriculum Change. | Scoffham, S. | A/ERIC |

| 2018 | Transformative Cosmopolitan Education and Gandhi’s Relevance Today. | Lang-Wojtasik, G. | A/ERIC |

| 2018 | Critical Realist Approaches to Global Learning: A Focus on Education for Sustainability. | Khazem, D. | A/ERIC |

| 2018 | Decolonizing Development Education Policy: The Case of Germany. | Bendix, B. | B/ERIC |

| 2017 | Sustainable Knowledge Transformation in and through Higher Education: A Case for Transdisciplinary Leadership. | Khoo, S.-M. | AB/ERIC |

| 2017 | Becoming Critical: A Challenge for the Global Learning Programme? | Huckle, J. | B/ERIC |

| 2016 | Sustainable distance learning for a sustainable world. | Bell, S. | AB/PsycInfo |

| 2016 | Global citizenship education: Everyday transcendence. | Gaudelli, W. | B/Scopus |

| 2016 | Understanding Learning in World Society: Qualitative Reconstructive Research in Global Learning and Learning for Sustainability. | Scheunpflug, A., Krogull, S., Franz, J. | A/ERIC |

| 2016 | Global Learning and Development as an Engagement Strategy for Christian Higher Education: A Macro Study. | Decker, A., Hawkins, G. | B/ERIC |

| 2016 | Protecting the Future: the Role of School Education in Sustainable Development--An Indian Case Study. | Bangay, C. | B/ERIC |

| 2016 | Analysing Key Debates in Education and Sustainable Development in Relation to ESD Practice in Viet Nam. | Balls, E. | B/ERIC |

| 2015 | Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship: Leadership, Collaboration, and Networking in Primary Schools. | Bennell, S.J. | B/ERIC |

| 2015 | CLICK: Arts Education and Critical Social Dialogue within Global Youth Work Practice. | Aubrey, M. | B/ERIC |

| 2015 | Civic Education for Sustainable Development and Its Consequences for German Civic Education Didactics and Curricula of Higher Education. | Brunold, A.O. | AB/ERIC |

| 2015 | The Phenomenon of “Being-In-Management” in Executive Education Programmes: An Integrative View. | Sewchurran, K., McDonogh, J. | A/ERIC |

| 2015 | The creation of interactive activity pods at a Recycling Education Centre. | Pickford, T., Ellis, L. | A/Scopus |

| 2014 | Global Learning for Global Colleges: Creating opportunities for greater access to international learning for 16–25 year olds. | Bentall, C., Bourn, D., McGough, H., Hodgson, A., Spours, K. | A/Scopus + ERIC |

| 2014 | Global Learning and Education: Key Concepts and Effective Practice. | Peterson, A., Warwick, P. | AB/Scopus |

| 2014 | Island development: Local governance under globalization. | Tsai, H.-M., Hong, S.-K. | B/Scopus |

| 2014 | Success and failure of grassroots innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the transition movement. | Feola, G., Nunes, R. | B/Scopus + A/SSCI |

| 2014 | Making a MEAL out of a Global Professional Learning Community: A Transformative Approach to Global Education. | MacCallum, C.; Salam, I. | B/ERIC |

| 2014 | Global Citizenship as a Floating Signifier: Lessons from UK Universities. | Moraes, S.E. | A/ERIC |

| 2014 | World-Mindedness of Students and Their Geography Education at International (IB-DP) and Regular Schools in the Netherlands. | Béneker, T., van Dis, H., van Middelkoop, D. | A/ERIC |

| 2013 | Mathematics Education Meets Development Education: The Competency ‘Mathematical Modelling’ Combined with Global Skills and Competencies in a Secondary School Project in Germany. | Schell-Straub, S. | B/ERIC |

| 2013 | Learning & transformative networks to address wicked problems: A golden invitation. | Waddell, S., McLachlan, M., Dentoni, D. | B/Scopus + A/SSCI |

| 2013 | A review of clean energy innovation and technology transfer in China. | Liu, H., Liang, D. | A/Scopus |

| 2012 | Critical distance: doing development education through international volunteering. | Diprose, K. | B/SSCI |

| 2010 | The Earth Charter Goes Interactive and Live with e-GLO: Using New Media to Train Youth Leaders in Sustainability on Both Sides of the Digital Divide. | Sheehan, M., Laitinen, J. | AB/ERIC |

| 2008 | Play locally, learn globally: Group selection and structural basis of cooperation. | Choi, J.-K. | A/Scopus |

| 2007 | Regional Centres of Expertise: Innovative Networking for Education for Sustainable Development. | Fadeeva, Z., Mochizuki, Y. | B/ERIC |

| 2006 | The United Nations decade of education for sustainable development, its consequences for international political education, and the concept of global learning. | Brunold, A.O. | A/Scopus |

| 2006 | School development through Education for Sustainable Development in Austria. | Rauch, F., Steiner, R. | A/Scopus + B/PsycInfo + ERIC |

| 2005 | Global learning and education for sustainable development. | Brunold, A.O. | A/Scopus + ERIC |

| 1994 | Information Technology and Global Learning for Sustainable Development: Promise and Problems. | Hall, B.W. | A/Scopus + B/SSCI |

| General and historical overviews | Historical context and development of field; ideological divergences; need for and value of GLSD; suggested future directions |

| Theoretical contributions | Knowledge formation, exchange, and transfer; inter- and transdisciplinarity; global–local collaboration and networks; universality or pluralism in values; motivation to engage in collaboration |

| Policy research | International agendas (UN, OECD); national policies and curricula; choice of learning content and competencies; need for critical global learning |

| Formal primary and secondary education | Position of GLSD with respect to curricular content; student learning outcomes; student motivation; leadership and whole-school engagement; collaboration with actors outside schools |

| Further and higher education | Institutional drivers; funding; institutional capacity; forms of including GLSD content in programs |

| Learning outside formal education | NGO action; global action networks/NGO networks; practical challenges; diverging priorities; self-identification as global citizens |

| North-South relationships | Unequal global power relationships; inequalities within countries; racism; shallow learning from exchanges; examples of partnerships for GLSD |

| Cross-cutting findings or topics | North–South power imbalances; question of shared language; issues funding GLSD; weaknesses both in digitally mediated communication and in physical exchanges; knowledge does not necessarily lead to action for sustainability |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nordén, B.; Avery, H. Global Learning for Sustainable Development: A Historical Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063451

Nordén B, Avery H. Global Learning for Sustainable Development: A Historical Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063451

Chicago/Turabian StyleNordén, Birgitta, and Helen Avery. 2021. "Global Learning for Sustainable Development: A Historical Review" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063451

APA StyleNordén, B., & Avery, H. (2021). Global Learning for Sustainable Development: A Historical Review. Sustainability, 13(6), 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063451