How Sport Tourism Event Image Fit Enhances Residents’ Perceptions of Place Image and Their Quality of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Image Fit

1.2. Place Image

1.3. Quality of Life

2. Hypotheses

2.1. Residents’ Image Fit for Place Image

2.2. Residents’ Image Fit for Quality of Life

2.3. Residents’ Place Image for Quality of Life

3. Methodology

3.1. Context of the Study

3.2. Data Collection and Instruments

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Profile

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

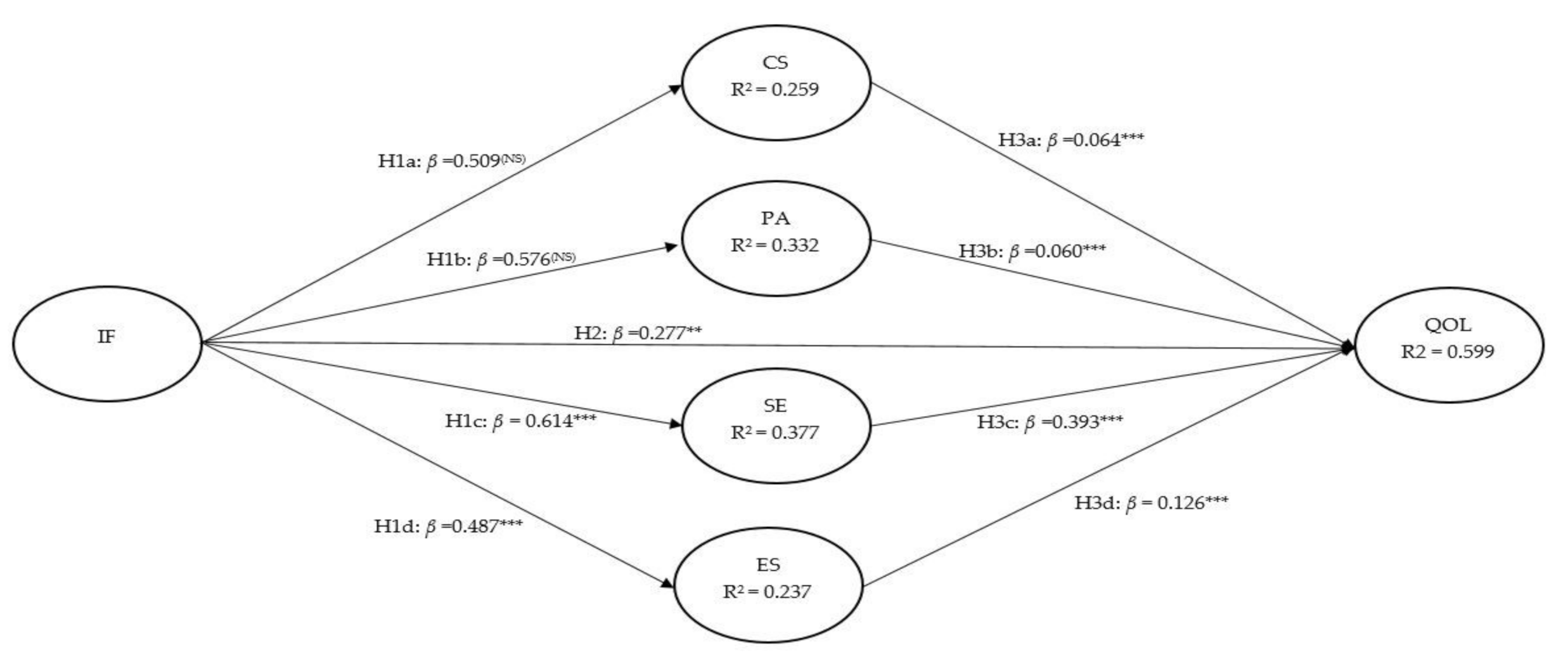

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Vivekadhish, S. Millennium development goals (MDGS) to sustainable development goals (SDGS): Addressing unfinished agenda and strengthening sustainable development and partnership. Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2016, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, J.W.; Rasmussen, K. Classifying Sustainable Development Goal trajectories: A country-level methodology for identifying which issues and people are getting left behind. World Dev. 2019, 123, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, I.; Darby, P. Sport and the Sustainable Development Goals: Where is the policy coherence? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2019, 54, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvina, K.; Kostyantyn, U.; Larysa, D.; Lidiia, R.; Irina, K.; Alina, U.; Olha, B.; Lolita, D.; Shengying, S. Sustainable development and the Olympic Movement. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 403–407. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, P.M.; Kelly, S.J.; Gill, C. Identifying objectives for mega-event leveraging: A non-host city case. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 36, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.; Gursoy, D.; Lau, K.L.K. Longitudinal impacts of a recurring sport event on local residents with different level of event involvement. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Yolal, M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Panosso Netto, A. Impact of trust on local residents’ mega-event perceptions and their support. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshimi, D.; Harada, M. Host residents’ role in sporting events: The city image perspective. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Jordan, J.S.; Funk, D.; Ridinger, L.L. Recurring sport events and destination image perceptions: Impact on active sport tourist behavioral intentions and place attachment. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, J.; Heslop, L.; O’Reilly, N.; Luk, P. Destination in a country image context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Wolfe, K.; Kang, S.K. Image assessment for a destination with limited comparative advantages. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Morais, D.B.; Kerstetter, D.L.; Hou, J.S. Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destinations. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Nunkoo, R. City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.; Simmons, C.J. When do social sponsorships enhance or dilute equity? Fit, message source, and the persistence of effects. ACR North Am. Adv. 2002, 29, 287–289. [Google Scholar]

- Oshimi, D.; Harada, M. The effects of city image, event fit, and word-of-mouth intention towards the host city of an international sporting event. Int. J. Sport Manag. Recreat. Tour. 2016, 24, 76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Z.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, K.C. It’s all about life: Exploring the role of residents’ quality of life perceptions on attitudes toward a recurring hallmark event over time. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Handbook of Quality-of-Life Research: An Ethical Marketing Perspective; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.A.; Andereck, K.L.; Pham, K. Designing for quality of life and sustainability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.; Hawkins, N. A tale of two cities—A commentary on historic and current marketing strategies used by the Liverpool and Glasgow regions. Place Branding 2006, 2, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Eaton, J. Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. J. Advert. 1999, 28, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, R.; Thompson, P. Determinants of sports sponsorship response. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, G.Y.; Quarterman, J.; Flynn, L. Effect of perceived sport event and sponsor image fit on consumers’ cognition, affect, and behavioral intentions. Sport Mark. Q. 2006, 15, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, S.; Beatty, S.E. Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence: An assessment of recall and affect. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 21, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, L.R.; Homer, P.M. Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 11, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M.A. An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.; Bennett, G. The impact of brand cohesiveness and sport identification on brand fit in a sponsorship context. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L. And now, a word from our sponsor—A look at the effects of sponsored content and banner advertising. J. Advert. 2003, 32, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. The interrelationship between sport event and destination image and sport tourists’ behaviours. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, T. The relationship of residents’ image of their state as a tourist destination and their support for tourism. J. Travel Res. 1996, 34, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Asplund, C.; Rein, I.; Haider, D. Marketing Places Europe: How to Attract Investments, Industries, Residents and Visitors to Cities, Communities, Regions, and Nations in Europe; Financial Times: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, R. City marketing, image reconstruction and urban regeneration. Urban Stud. 1993, 30, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, A.; Aitken, R.; Thyne, M.; Gnoth, J. Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.X.; Hui, T.K. Residents’ quality of life and attitudes toward tourism development in China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Kalavar, J.M.; Melubo, K. Tourism and community well-being: The case of the Maasai in Tanzania. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C. Mega-events and host-region impacts: Determining the true worth of the 1999 Rugby World Cup. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Brown, D.O. A comparison of the views of involved versus noninvolved citizens on quality of life and tourism development issues. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Uysal, M. Measuring the effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life: Further validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 69, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Karadakis, K.; Gibson, H.; Thapa, B.; Walker, M.; Geldenhuys, S.; Coetzee, W. Quality of life, event impacts, and mega-event support among South African residents before and after the 2010 FIFA World Cup. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Larson, B.V.; Swanson, S.R. Image transfer in corporate event sponsorship: Assessing the impact of team identification and event-sponsor fit. Int. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2009, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D.R.; Crompton, J.L. Tactics used by sports organizations in the United States to increase ticket sales. Manag. Leis. 2004, 9, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T. Schema-Triggered Affect: Applications to Social Perception, Affect and Cognition, Proceedings of 17th Annual Carnegie Mellon Symposium on Cognition, 1982; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1982; pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stylidis, D. Residents’ place image: A cluster analysis and its links to place attachment and support for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Breuer, C. Image fit between sport events and their hosting destinations from an active sport tourist perspective and its impact on future behaviour. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.Q.; Li, M.; Shen, H. Developing a measurement scale for event image. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.C.; Phau, I. Extending symbolic brands using their personality: Examining antecedents and implications towards brand image fit and brand dilution. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Ritchie, B.W.; Adair, D. Sport Tourism: Interrelationships, Impacts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2004; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Tianzhongmarathon. About Tianzhongmarathon. Available online: https://www.tianzhongmarathon.com/blank-1 (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger III, P.J. Exploring synergetic effects of social-media communication and distribution strategy on consumer-based Brand equity. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2020, 10, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Ting, H.; Ramayah, T.; Chuah, F.; Cheah, J. A review of the methodological misconceptions and guidelines related to the application of structural equation modeling: A Malaysian scenario. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2017, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.H. Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J., III. Exploring consumer–brand engagement: A holistic framework. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger, P.J. The influence of perceived social media marketing elements on consumer–brand engagement and brand knowledge. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Kössler, C.; Schlemmer, P.; Peters, M. Influence of event and place image on residents’ attitudes toward and support for events. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 1096348020919502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, G.C.; Mak, A.H. Exploring the discrepancies in perceived destination images from residents’ and tourists’ perspectives: A revised importance–performance analysis approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1124–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Yang, S.C. Residents’ attitudes toward support for island sustainable tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez del Rio-Vazquez, M.E.; Rodríguez-Rad, C.J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.Á. Relevance of social, economic, and environmental impacts on residents’ satisfaction with the public administration of tourism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, A.J.A.; Custódio, M.J.F.; Perna, F.P.A. “Are you happy here?”: The relationship between quality of life and place attachment. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 6, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund-de Witt, A. Rethinking sustainable development: Considering how different worldviews envision “development” and “quality of life”. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8310–8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mosko, E.; Munsters, W. Sport tourism: A growth market considered from a cultural perspective. Ido Mov. Cult. J. Martial Arts Anthropol. 2018, 18, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vehmas, H. Rationale of active leisure: Understanding sport, tourism and leisure choices in the Finnish society. Ido Mov. Cult 2010, 10, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Cynarski, W.J.; Obodyński, K.; Porro, N. Sports, Bodies, Identities and Organizations: Conceptions and Problems; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego: Rzeszów, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, H.K. Southern Hospitality: Tourism and the Growth of Atlanta; University Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Starnes, R.D.; Blevins, B.; Jackson, H.H.; Ownby, T.; Pierce, D.S. Southern Journeys: Tourism, History, and Culture in the Modern South; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Item | Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Fit (IF) | IF1 | 0.921 | 0.871 | 0.694 |

| IF2 | 0.930 | |||

| IF3 | 0.912 | |||

| Community Services (CS) | CS1 | 0.799 | 0.897 | 0.744 |

| CS2 | 0.813 | |||

| CS3 | 0.884 | |||

| Physical Appearance (PA) | PA1 | 0.800 | 0.902 | 0.754 |

| PA2 | 0.902 | |||

| PA3 | 0.883 | |||

| Social Environment (SE) | SE1 | 0.883 | 0.892 | 0.733 |

| SE2 | 0.909 | |||

| SE3 | 0.811 | |||

| Entertainment Services (ES) | ES1 | 0.831 | 0.953 | 0.871 |

| ES2 | 0.847 | |||

| ES3 | 0.889 | |||

| Quality of Life (QOL) | QOL1 | 0.933 | 0.944 | 0.848 |

| QOL2 | 0.937 | |||

| QOL3 | 0.930 |

| Construct | IF | CS | PA | SE | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Fit (IF) | |||||

| Community Services (CS) | 0.754 | ||||

| Physical Appearance (PA) | 0.658 | 0.783 | |||

| Social Environment (SE) | 0.794 | 0.748 | 0.678 | ||

| Entertainment Services (ES) | 0.621 | 0.677 | 0.802 | 0.637 | |

| Quality of Life (QOL) | 0.599 | 0.662 | 0.701 | 0.553 | 0.704 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | β | t-Value | f2 | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | IF → CS | 0.509 | 1.079(NS) | 0.005 | 0.259 | 0.249 |

| H1b | IF → PA | 0.576 | 0.95(NS) | 0.004 | 0.332 | 0.327 |

| H1c | IF → SE | 0.614 | 6.279 *** | 0.181 | 0.377 | 0.370 |

| H1d | IF → ES | 0.487 | 2.147 * | 0.019 | 0.237 | 0.229 |

| H2 | IF → QOL | 0.277 | 4.612 *** | 0.105 | 0.599 | 0.413 |

| H3a | CS → QOL | 0.064 | 12.143 *** | 0.349 | ||

| H3b | PA → QOL | 0.060 | 13.164 *** | 0.496 | ||

| H3c | SE → QOL | 0.393 | 14.017 *** | 0.606 | ||

| H3d | ES → QOL | 0.126 | 10.15 *** | 0.311 | ||

| H4a | IF→ CS → QOL | 0.033 | 1.067 (NS) | |||

| H4b | IF → PA → QOL | 0.035 | 0.945 (NS) | |||

| H4c | IF → SE → QOL | 0.241 | 5.834 *** | |||

| H4d | IF → ES → QOL | 0.061 | 2.151 * |

| Construct | PLS | LM | PLS-LM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | Q2 | RMSE | Q2 | RMSE | Q2 | |

| QOL1 | 1.007 | 17.01 | 1.02 | 17.139 | −0.014 | 0.017 |

| QOL2 | 0.91 | 13.909 | 0.92 | 14.083 | −0.008 | 0.012 |

| QOL3 | 0.991 | 16.781 | 0.998 | 17.014 | −0.005 | 0.007 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsu, B.C.-Y.; Wu, Y.-F.; Chen, H.-W.; Cheung, M.-L. How Sport Tourism Event Image Fit Enhances Residents’ Perceptions of Place Image and Their Quality of Life. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198227

Hsu BC-Y, Wu Y-F, Chen H-W, Cheung M-L. How Sport Tourism Event Image Fit Enhances Residents’ Perceptions of Place Image and Their Quality of Life. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198227

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsu, Bryan Cheng-Yu, Yu-Feng Wu, Hsin-Wei Chen, and Man-Lai Cheung. 2020. "How Sport Tourism Event Image Fit Enhances Residents’ Perceptions of Place Image and Their Quality of Life" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198227

APA StyleHsu, B. C.-Y., Wu, Y.-F., Chen, H.-W., & Cheung, M.-L. (2020). How Sport Tourism Event Image Fit Enhances Residents’ Perceptions of Place Image and Their Quality of Life. Sustainability, 12(19), 8227. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198227