1. Introduction

The importance of collaboration, governance and partnerships for a balanced and sustainable development of any sector has been increasingly acknowledged [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Tourism, probably more than other sectors, is a relational phenomenon, and its understanding is highly dependent on the relationships between its different components and on regarding the destination as a system [

5,

6]. The (strategic) management of a tourism destination itself is based on cooperative planning, involving joint interactions that bring both collective and individual benefits [

7]. Moreover, collaboration is regarded as a key aspect for achieving competitive advantages [

8] and for embarking on a sustainable path of tourism development [

2,

9]. Against this background, there is no surprise that, during recent years, the literature has seen a growing interest in studying the matter of collaboration in tourism [

2,

10,

11].

Studies that deal with collaboration in tourism are traditionally framed by Freeman’s stakeholder theory or by collaboration theory [

12]. According to the former [

13,

14], planning and management of a tourist destination should pay great(er) attention not only to the interest of each stakeholder, but also to the relationships established among all stakeholders involved. From a similar perspective, collaboration theory discusses ‘a process of joint decision-making among key stakeholders of a problem domain about the future of that domain’ [

12]. However, despite significant theoretical advances, empirical evidence is still rather scarce, especially because of the difficulty of gathering the necessary data and of conducting objective analyses on this topic. Consequently, there is still much to uncover regarding the peculiarities and challenges of collaboration in destinations, as the facets of collaboration are extremely diverse and dynamic and therefore very difficult to grasp.

A structural approach for inquiring about collaboration is a partial answer to these challenges, but a highly significant one because of its capacity to unveil peculiarities of tourism networks. The structure of the network is defined as the combination of a systems’ components and refers both to its individual elements and to the ties that connect these elements [

15]. In addition to structural features, tourism research is highly interested in inquiring about forms of collaboration, which are approached from diverse perspectives, such as the type of relationships created [

16], the purpose for which stakeholders collaborate [

17,

18] or the level of formalism of the relationships [

19,

20].

Social Network Analysis (SNA) is one of the main approaches, and one of the most powerful to be employed nowadays for better understanding of collaboration mechanisms in tourism [

21,

22] and for providing empirical evidence on this subject. The methods of SNA make it possible to identify and interpret the collaboration behaviour inside tourist destinations from a quantitative perspective, by starting from a qualitative analysis of certain case studies [

23]. However, despite the fact that there is a growing number of studies using SNA to unveil patterns in tourism collaboration, the application of network science in tourism studies is considered to be in an early stage of development [

24], being regarded as a field that is still insufficiently explored [

22]. Consequently, we argue that the applicability of SNA in tourism studies should be regarded as a highly fertile area, in the direction of advancements of stakeholder and collaboration theories, as well as for deepening our understanding on how tourism networks work in various contexts.

The aims of this paper are (1) to operationalise Social Network Analysis in examining the structural characteristics of tourism networks and the forms of collaboration specific to such networks and (2) to reveal through this approach the weaknesses and strengths of tourism collaboration from a destination management perspective. The aim of identifying deficiencies inside a tourism network is directly related to the choice of a stagnating destination as a case study, in this case Vatra Dornei, a spa resort in Romania, highly representative for the particular context of a post-socialist territory. As such, the paper starts from the premise that the stagnating character of a destination is related to deficiencies concerning collaboration between its stakeholders. The paper contributes to the growing empirical literature on tourism collaboration while also delivering evidence for the utility of SNA for understanding tourism collaboration.

The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction,

Section 2 provides a literature review on theoretical and empirical approaches to tourism collaboration.

Section 3 presents the study area, data and methods employed.

Section 4 describes the results, while

Section 5 discusses the findings and their implications for theory and policy building.

2. Literature Review: Social Network Analysis in Tourism Collaboration Research

The systemic character of tourism, derived from the interdependence between its various involved stakeholders [

25,

26], determines a growing interest in studying collaboration in tourism destinations. Collaboration is also growing in importance through the more recent concept of ‘collective impact’ [

27], as this concept implies that the sustainability of a destination can only be achieved if it is regarded as a common purpose for all stakeholders involved, who therefore have to collaborate towards this goal [

28]. The existing literature shows that collaboration relationships between tourism stakeholders can take many forms and are approached under various names, depending on the context. Researchers mostly discuss matters related to tourism networks [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], tourism local systems [

34,

35] or tourism clusters [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. While these concepts may imply certain conceptual particularities, all of them revolve around the same idea: the existence of a set of stakeholders that collaborate to achieve both individual and collective goals.

During recent years, acknowledging the importance of tourism collaboration has been accompanied by an increasing popularity of Social Network Analysis (SNA) in tourism literature. The applicability of SNA in tourism studies is justified by the fact that tourist destinations can be perceived as collaboration networks of complementary organisations [

41] or as ‘groups of independent suppliers interconnected in order to provide a global product’ [

26]. The evolution of network analysis in tourism literature mirrors the evolution of network science in all fields. As such, the approaches developed from the analysis of basic topological features of networks to the investigation of complex and dynamic processes and more recently to the analysis of multidimensional networks [

24].

2.1. Exploring Basic Structural Features of Tourism Networks

The structural characteristics of tourism systems are considered to be strongly connected to the collaboration behaviour inside tourism destinations [

42]. Not surprisingly, network analysis in tourism has mainly been concerned with ensuring a deep understanding of the basic structural features of the networks. Often, examining the structure of a particular destination has been stated as the only aim of such studies, due to the complexity of the structure of a tourism network. In this regard, results from existing research can be classified in two categories.

First, there is an almost ubiquitous interest in inquiring into networks’ general level of cohesion. Density, average degree or modularity indicate the state of collaboration in destinations in terms of intensity of interaction and connectivity among stakeholders. Related research shows that tourism destinations appear to be generally characterised by a low level of collaboration, with densities between 4.2% and 9.2% for case studies from Portugal [

43], between 6% and 14% for Australian destinations [

26] or as low as 0.3% for Elba destination, Italy [

44]. These empirical results led to a general perception that tourism stakeholders have the tendency to avoid collaboration or that they simply do not take full advantage of its potential benefits [

24]. More complex approaches aim at examining matters of assortativity and modularity. Through this approach, Valeri and Baggio [

45] found that the Italian tourism system has a level of self-organisation that determines the creation of informal communities, which are highly relevant in a destination’s governance.

Second, there is great interest in employing SNA for revealing power hierarchies inside networks. In this regard, several streams of research can be identified. One stream of research produced evidence on the nature and the role of central stakeholders inside destinations. Researchers showed, inter alia, that Destination Management Organisations (DMOs) stand out as central stakeholders in destinations [

46,

47] and that they considerably enhance collaboration. On the contrary, the lack of a central stakeholder, capable of coordinating the collaboration process, can be associated with a generally low level of collaboration [

48]. Another stream of research went further and examined types of power inside destinations. In this context, some researchers found preliminary evidence showing that knowledge-based power plays the most important role in determining the influence of stakeholders inside tourism networks [

49]. Finally, a third stream of research incorporates studies that take a longitudinal approach and look at the evolution of power dynamics in destinations. Such studies have greatly enriched our knowledge. One of them revealed, for example, an increasingly decentralised structure of Korean tourism networks over the last 50 years, due to the growth of the number of organisations involved, with local government, private sector and other stakeholders gaining considerable influence over the years [

50].

This summary of previous literature provides an image of the main concerns in network analyses in tourism studies that deal with basic structural characteristics of collaboration networks. It underlines the wide applicability of SNA for better understanding the structure of tourism destinations, but it also sets the background for more complex approaches to tourism networks.

2.2. Towards the Investigation of Dynamic and Complex Processes

Gradually, the interest for applying SNA in tourism studies has shifted towards more complex approaches. These approaches aim at looking beyond the structural characteristics of networking by analysing them in relation to particular issues and processes related to tourism. Two main topics of interest that employ SNA can be distinguished in the literature.

A first topic of high interest that relies on SNA concerns destination management and its dependency on collaboration between tourism stakeholders. Researchers found evidence for the existence of a direct relationship between the level of tourism development and particularities of networking between stakeholders [

18], as well as for the fact that successful sustainable tourism policymaking requires the involvement of stakeholders from multiple economic sectors concerned with matters of sustainability, not only from tourism stakeholders [

51]. Other studies have drawn conclusions on the existence of a significant shift in power inside networks, with private stakeholders gaining increasing power [

52].

A second central topic that relies on SNA is the relationship between tourism and innovation [

33,

43,

53,

54]. Empirical results show that the developed relationships must be geographically diverse, with emphasis on the necessity of establishing international ties for innovation in tourist destinations [

33]. Nonetheless, the preference of tourism stakeholders for establishing collaboration relationships in their proximity is a reality that defines the tourism sector which is, among other cases, empirically proven for an Italian region [

53].

Overall, it can be concluded that the applicability of Social Network Analysis has evolved to a great extent in tourism literature. This evolution is reflected both in the techniques employed and in the territorial contexts and specific tourism issues addressed. A transversal aim, stated in many of the reviewed papers, is that of illustrating the utility of Social Network Analysis for understanding tourism realities in destinations, an aim reached by analysing various distinct territories and types of tourism-related issues. While the diversification of approaches and their growth in complexity is to be further encouraged, the fact that even recently there are studies focusing on basic structural features of networks as a main purpose [

45,

50] indicates that there is still much to be explored regarding what is perceived as basic characteristics of collaboration networks in tourism.

Against this background, the present study adds to the literature further evidence of the utility of SNA’s methods and measures in tourism analysis through a classic approach on tourism networks but for a previously unstudied territory. As such, the purpose of this study is to contribute to the knowledge related to tourism collaboration mechanisms, with focus on identifying deficiencies in the way that a stagnating destination functions at the level of stakeholders’ interaction.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

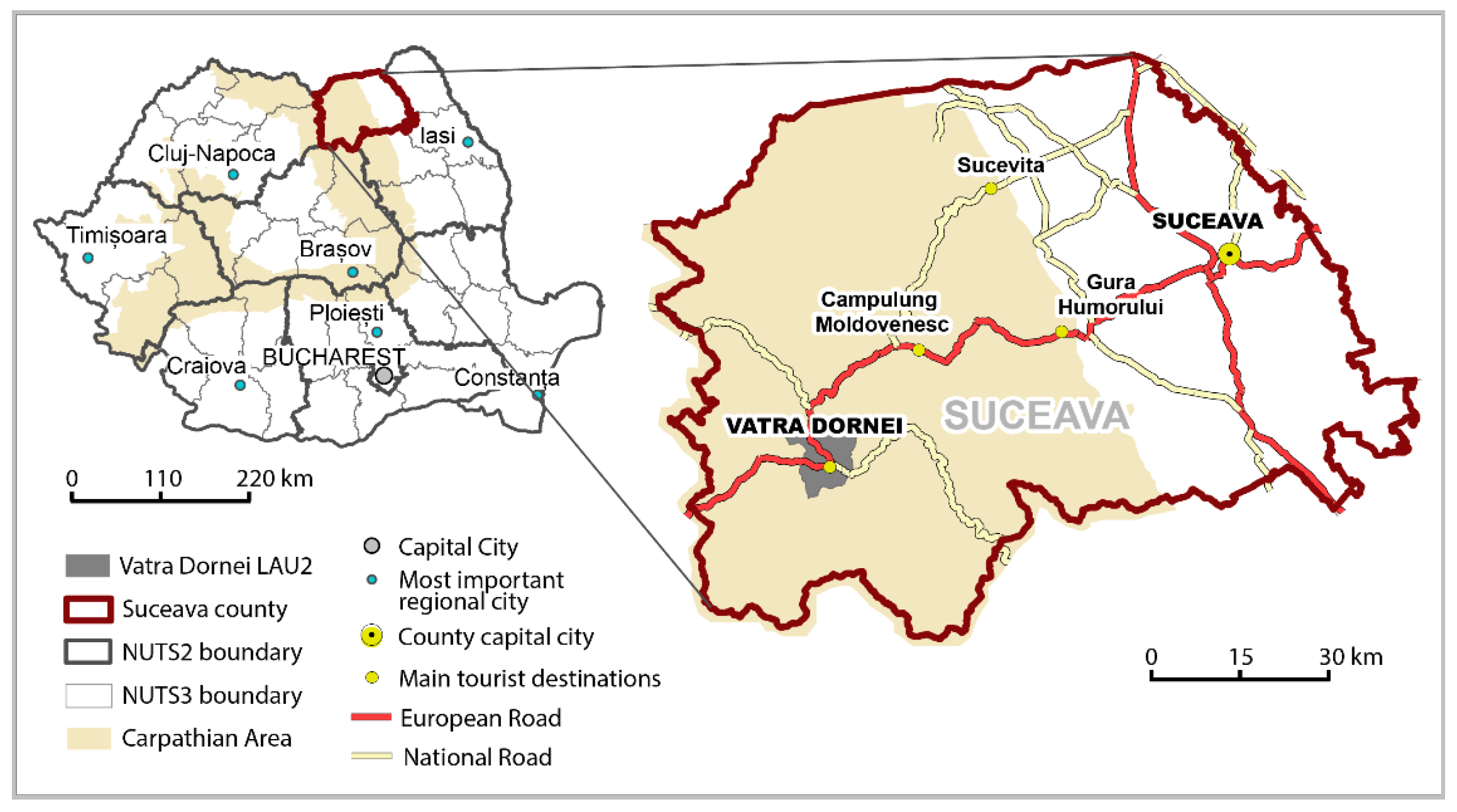

A destination with theoretically complex and well-developed relational dynamics has been chosen as a case study, namely Vatra Dornei (

Figure 1). This destination displays a long tourism tradition, which could imply a significant level of familiarity between its stakeholders and a higher probability for the stakeholders to have established strong relationships. At the same time, Vatra Dornei is placed in a geographical area with a high density of tourism activity, which favours spillover effects and implicitly collaboration interactions with neighbouring areas/destinations.

Administratively, Vatra Dornei is a city that belongs to Suceava County (

Figure 1), which is subordinated to Northeast Region of Romania (NUTS2). A defining geographical characteristic of Vatra Dornei is its peripheral character, which has a high impact on the development of tourism. Vatra Dornei represents a peripheral area in relation to the main urban centre in the county, Suceava, as well as in relation with the main urban centres from the Northeast NUTS2 region and from the entire country (

Figure 1). At the same time, the Northeast region itself is considered a peripheral area, based on its position in Romania and in the European Union. Moreover, Vatra Dornei is situated in one of the most peripheral areas of the country, the Carpathian Mountains, characterised by the weakest accessibility and connectivity in Romania [

55].

From a historical point of view, the city is part of Bucovina Region, a territory with distinct identity due to the fact that in the past it has been under the administration of the Habsburg Empire, which significantly influenced the development of the city. Due to the discovery of mineral waters here during the 19th century [

56], Vatra Dornei has been known as a spa resort since that time. Later, the interest of the communist administration during the second half of the 20th century for fostering mass tourism related to spa tourism [

57] further encouraged the development of the city as a spa resort. Currently, tourism in Vatra Dornei continues its tradition as a spa resort, but it also relies on winter sports and on the mountainous areas around the town, which favoured the development of active tourism in the area, starting from the first half of the 20th century [

58].

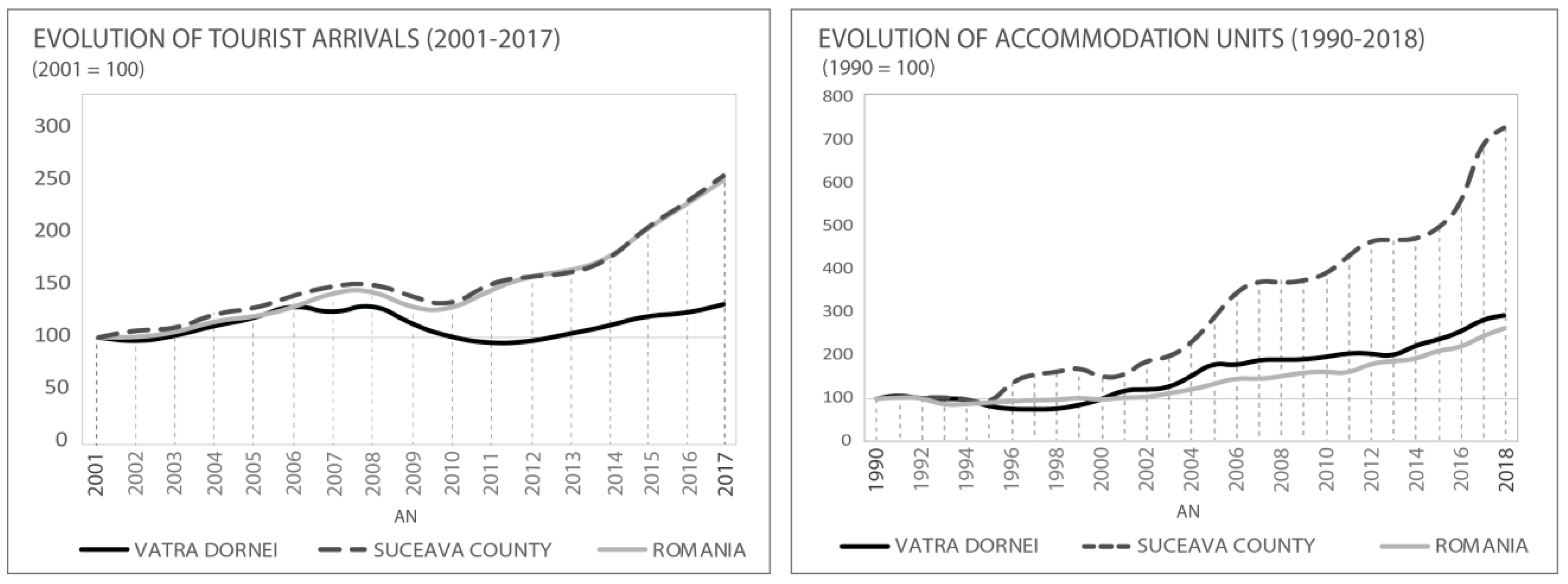

It is important to consider recent tourism trends in Vatra Dornei when inquiring about collaboration between stakeholders in the destination, so that the background of the identified collaboration behaviours is presented. Despite the fact that tourism is one of the main economic activities in the town at present, Vatra Dornei appears to be a stagnating destination, especially in terms of tourist arrivals (

Figure 2). Compared to the regional (Suceava county) and national context, Vatra Dornei continued its path to decline even long after the economic crisis in 2008, failing to reach again its level from before the crisis. In terms of tourism supply, Vatra Dornei manifests similar growth rates to those specific for Romania, while the growth of the entire county is considerably higher than it is in Vatra Dornei. Overall, this evolution brings attention to potential issues in the current management of the destination, especially since this resort develops at a significant slower pace than other destinations in the county. However, causes for this discrepancy in the region concerning the development of accommodation units might also be found in the fact that Vatra Dornei is already a mature destination being in the first position in terms of tourism supply during the last decades, with 2607 bed places distributed in 63 accommodation establishments (2019) [

59]. Data show that while in 1990 Vatra Dornei owned 33% of the total number of bed places in Suceava County, in 2019 this value decreased to 21%. This emphasises the notable emergence of many rural destinations after 2000, which led to a more uniform distribution of accommodation establishments across the county, and which naturally manifest higher growth rates in the first stages of their destination lifecycle [

60].

Overall, Vatra Dornei is a mature, stagnating destination, a type of tourism territory that has rarely been approached in studies concerned with collaboration dynamics. As such, the present paper provides insights into the mechanisms of collaboration that are specific to this type of destination, which could give answers to deficiencies specific to stagnating destinations through further such case studies.

3.2. Data Collection

The data for the analysis were gathered through a semi-structured interview, which was organised in two sections. The first section addressed matters related to main issues of tourism in Vatra Dornei and perceptions of collaboration. The second section focused on the collaboration relationships of each respondent. The main purpose of this section was to identify the most important collaboration relationships that each stakeholder developed in the previous 24 months, followed by inquiring into details on the purpose and nature of each relationship, in order to identify the forms of collaboration that are most prevalent. The forms of collaboration are, as such, defined in this case as the tourism activities for which stakeholders collaborate. The geographical origin of the collaboration was also a matter of interest, as collaboration with stakeholders at each geographical level has distinct implications. Consequently, the collaboration relationships were classified into four categories defined from a geographical perspective: local (from Vatra Dornei), regional (from Suceava County), national (from Romania, apart from Suceava County) and international (from other countries).

The selection of stakeholders for interviews was conducted by means of snowball sampling. This technique ensures that as much of the relevant stakeholders as possible were covered through the interviews [

61]. The use of the snowballing sampling is a frequent approach when studying matters related to a collaborative process through stakeholder interviews [

26,

46,

61], especially when small groups are regarded [

62]. From a practical standpoint, its application consists in a sequence of different steps that, in our case, were implemented as follows. A series of 10 most important stakeholders were first identified, through official documents and official travel websites, and then interviewed. These stakeholders were (i) managers of public institutions related to tourism or (ii) owners or managers of private firms providing accommodation or other services for tourists. The respondents from each of these 10 institutions and firms were asked to identify other key stakeholders regarding the development of the destination according to their perception and knowledge. Then, the most recurring names were included in the list with the purpose of being interviewed, leading to a total of 24 interviews that were realised. The interviews were carried out in February–April 2019, through face-to-face interaction with the stakeholders. The duration of the interviews varied between 10 min and 30 min.

Table 1 displays the list of interviewed stakeholders, as well as their main attributes.

Data were collected from 6 representatives of the public sector: the City Hall, the Tourism Information and Mountain Rescue Centre (TourMountResc), the Cultural House (Inst2), two museums (TAtt4, TAtt5) and a ski slope under the administration of the City Hall (TAtt8). The private stakeholders were mostly accommodation establishments, to which were added 2 other ski slopes (TAtt7, TAtt10), a stud farm (TAtt1) and the only incoming travel agency in the city (Tag3).

Concerning the general background of the interviewed stakeholders, as well as their general attitude towards collaboration (

Table 1), three main aspects are worth noticing. Firstly, stakeholders unanimously consider collaboration important, but opinions vary when regarding the perceived benefits attained from existent collaboration relationships: local public administration and institutions had the most positive opinion about their collaboration relationships, while representatives of accommodation establishments were more sceptical. Secondly, half of the interviewed stakeholders indicated that their opinion or involvement in strategy and policy design for tourism development in Vatra Dornei was never demanded. All of these stakeholders belong to the private sector and constituted 66% of all the private stakeholders interviewed. This should be seen as a particular problem from a policy perspective, as the involvement of all the stakeholders in decision-making is considered a precondition for efficient collaboration and for the sustainable development of the destination [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. However, the lack of involvement of these stakeholders in strategy and policy design does not impede them from being part of other local tourism collaboration networks. Thirdly, the respondents’ average years of experience in the field of tourism is of 12.9 years, which (i) ensures a high level of knowledge of the local tourism context from their part and (ii) makes their opinion regarding collaboration issues reliable for the purpose of our study.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

UCINET 6 for Windows [

64] was used to analyse the structure of the network and the individual features of the stakeholders that constitute it. The software allows one to compute various measures of the network and centrality values for the stakeholders, starting from the coded responses of the interviews.

A network is an expression of a social system, being composed by nodes, which are the entities that form the system, and by the ties that connect these nodes, which are the relationships between the entities [

65]. In the present case, the nodes are represented by stakeholders involved in tourism activities, while a tie consists of a collaboration relationship with another stakeholder. These ties have been indicated by each interviewed stakeholder, and the total number of nodes that forms the network is composed of the number of interviewed stakeholders (24) and by those stakeholders that they indicated as collaborators (112).

Since the study aimed at providing a thorough image of the structure of the network, both global measures and measures at the level of the nodes were computed. First, the global measures of density and average degree were analysed. The density represents the ratio between the existent ties and the total possible ties in a network. The density of a tourism network informs about strength of relations, trust, products and information exchange and, of course, about the general level of communication in a destination [

26,

33]. The average degree is complementary to density, providing a simpler image of the interactions inside a network, namely the average number of ties specific to each node [

65].

Furthermore, centrality measures, calculated at the level of nodes, add to the analysis by providing information regarding the ‘prominence or the influence that some stakeholders or elements have over others, due to their particular situation within the network’ [

22]. Degree centrality and betweenness centrality were calculated for the stakeholders of the Vatra Dornei network. Degree centrality indicates the effective ties each stakeholder has with other stakeholders, in terms of relationships that each stakeholder indicated (OutDegree) and of relationships that other stakeholders indicated with a particular stakeholder (InDegree). On the other hand, betweenness centrality emphasises the potential of a node to control communication inside the network [

66]. When calculated for a particular node, this measure considers the proportion of all the shortest paths from one node to another (except for the node the measure is calculated for) that pass through that particular node. All resulted proportions, for all potential pairs of nodes, are summed, resulting a single value for each node. The higher the value for a node, the more central that particular node is, indicating that it is situated across a high number of shortest paths inside the network [

65].

4. Results

4.1. General Level of Collaboration in Vatra Dornei

Despite a unanimous acknowledgment of collaboration as being essential for the development of a tourist destination (

Table 1), it appears that the network is created through 231 ties, which represent only 1.3% of the total possible ties between the 136 stakeholders included in the network (

Table 2). Therefore, Vatra Dornei is characterised by a low level of collaboration between the stakeholders when considering all stakeholders involved. If calculated only for the local stakeholders, 3.1% of the possible connections are established, which does not indicate a high density either, but at least a higher level of cohesion at the local level (only local stakeholders), compared to the global network (stakeholders from local, regional, national and international levels). However, these results have to be regarded with caution, as the low level of collaboration identified is also partly influenced by the rather reduced number of interviewed stakeholders, compared to the total number of stakeholders included in the network.

The local network of the destination, namely the one composed only of relationships between stakeholders from Vatra Dornei, comprises 68 stakeholders. While all relevant local public administration, institutions and tourism attractions are included in this network, in terms of tourism supply, only 49% of the total accommodation establishments from Vatra Dornei appear as collaborators. This sample of local stakeholders is influenced by the number of interviewed stakeholders, but it also illustrates a potential lack of involvement in collaboration initiatives from half of the hospitality representatives, as they are not present as collaborators in the list of any of the interviewed stakeholders.

In terms of relationships between private and public sectors, stakeholders from both sectors are more predisposed to collaborate with other stakeholders from their own category. As such, rather poor communication is identified between public and private stakeholders, with only 32% of relationships established by private stakeholders being with public ones and around 45% of the relationships established by public stakeholders, involving private stakeholders.

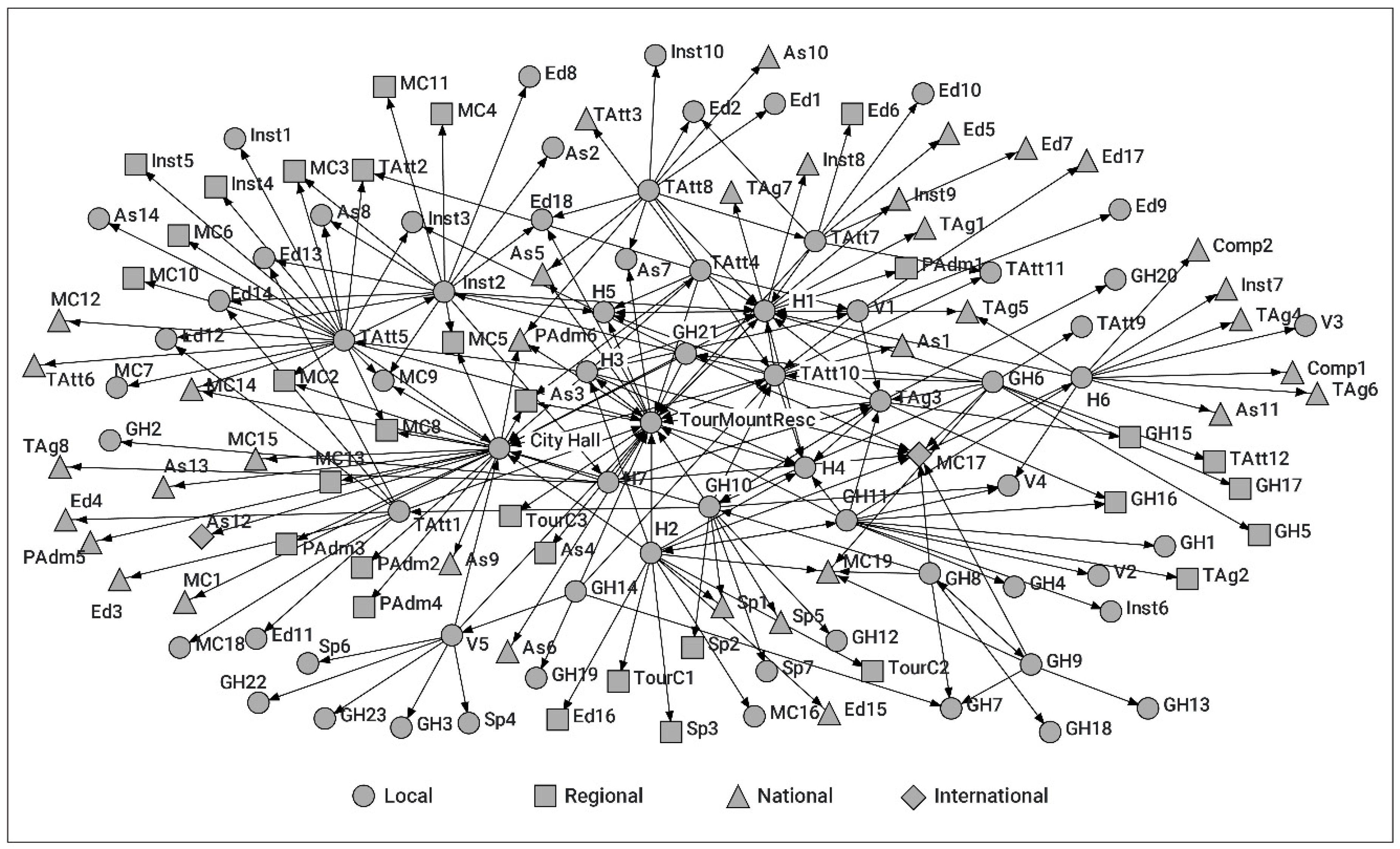

The tourism network in Vatra Dornei is dominated by local stakeholders, with 50% of the members of the network belonging to this geographical level (

Table 3 and

Figure 3). The regional and national levels own similar shares in the network, with 22.8% and 25.7%, respectively, of the stakeholders. Two international stakeholders account for the remaining 1.5% of the relationships: an online booking platform and a winter sports association. The very low share of international collaborators might be associated with the pronounced peripheral character of the destination, which might hinder a higher international visibility of the destination.

4.2. Forms of Collaboration

The purpose for which stakeholders collaborate is an important characteristic of the collaboration mechanisms inside a destination, as each purpose determines a particular form of collaboration. A pair of stakeholders that established a collaboration relationship can be engaged in one or several forms of collaboration, according to their common goals and priorities. In Vatra Dornei, the predominant purpose of collaboration is that of marketing and promotion, with 181 of the total pairs of stakeholders that collaborate (78%) being engaged in this type of tourism activity (

Table 4). According to insights gained from the interviews, three distinct situations are most frequently indicated by the 24 stakeholders: (i) a certain stakeholder that is promoted by another, generally the second one being a media channel; (ii) mutual promotion between the two stakeholders, which generally apply for stakeholders from the same category or from similar categories; (iii) collaboration initiatives for promoting the destination as a whole.

A second important purpose for which stakeholders collaborate is for providing necessary goods and services, an activity highly related to the complementarity between different categories of stakeholders. The collaboration relationships established for strategy and policy development have a considerably lower frequency, of 9.5%, which is similar to that of knowledge exchange and research (9.1%) and products creation (7.8%).

4.3. Centrality and Power Inside the Vatra Dornei Tourism Destination

The centrality measures for the Vatra Dornei network point out a limited number of central stakeholders (

Table 5) and therefore not many members with a real capacity to make decisions that influence the overall manner in which the network functions. The central stakeholders are determined by the number of relationships established: the higher the number of relationships that a stakeholder establishes, the more central he is. In terms of betweenness centrality, besides the number of relationships, a central stakeholder is also defined by his position in relation to the other stakeholders and implicitly by his capacity to connect other stakeholders between themselves, as it is situated across many shortest paths between each pair of stakeholders in the network.

The degree centrality indicates two different and complementary perspectives regarding the stakeholders’ relationships. The OutDegree values illustrate the number of connections indicated by each stakeholder, while the InDegree values represent the relationships with that particular stakeholder declared by other stakeholders that were interviewed. As such, the InDegree is a more relevant indicator of how central and influential a certain stakeholder is inside a network. In this case, the Tourist Centre and Mountain Rescue Service stands out as the most frequent collaborator indicated by the interviewed stakeholders, with 15 collaborators (

Table 5). The hierarchy is significantly diverse, with a hotel owning the second position (H1) and the local public administration a third position. These are followed by media channels, tourist attractions, the local travel agency and other accommodation establishments.

The betweenness centrality gives further information regarding the stakeholders’ position and points out the most influential ones, who have the capacity of connecting the members that do not collaborate in the network. The highest values of this measure (

Table 6) indicate the stakeholders who hold control over the communication in the network, and the considerable distance between the first position(s) in the hierarchy and the following ones indicates the reduced number with a real control and influence in the network. The Tourist Centre and Mountain Rescue Service is the most central stakeholder in the network, with theoretically the most significant capacity of facilitating the connection between the stakeholders. The first positions in this hierarchy are diverse in terms of the category each stakeholder belongs to. The local public administration is not a prominent stakeholder in the tourism network of Vatra Dornei, and its position appears even more insignificant related to its capacity of mediating connections among all the members when regarded only inside the local network of tourism stakeholders.

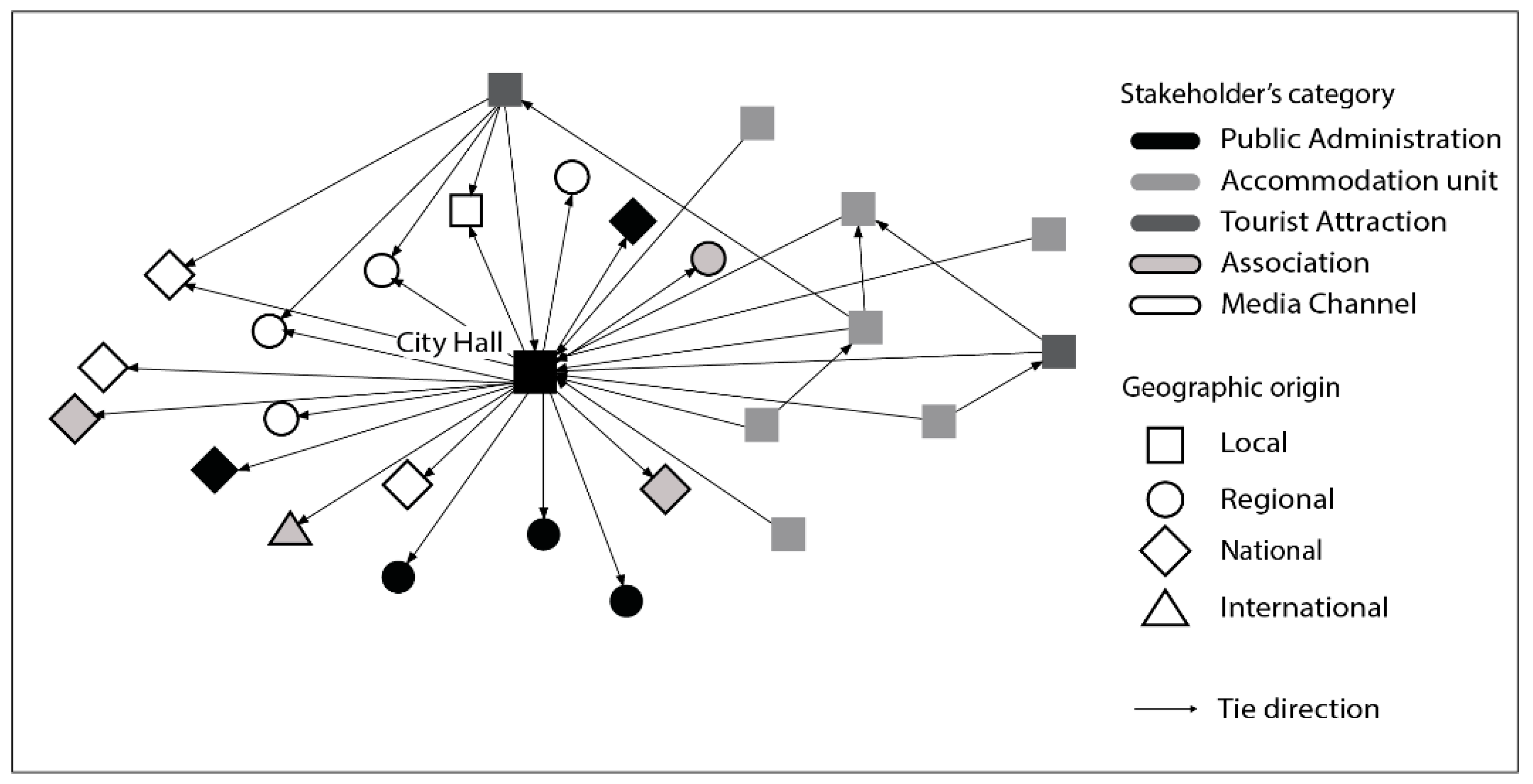

4.4. Egonet of the Local Public Administration

The relationships established by the local public administration are relevant due to the (theoretically) important role that it has for the development of a tourism destination and therefore due to the influence that its relationships may have for the destination. The collaboration behaviour of the public administration has to be regarded from two perspectives: (i) the extent to which it is connected on a local level and therefore has the potential to coordinate the tourism stakeholders, and (ii) the level of internationalization that it confers to the destination, through external ties, which have a central role in enhancing the visibility and success of the destination.

At the local level, results reveal a low number of collaborators, which poses problems in terms of network strength. Moreover, most of the local collaborators are stakeholders who indicated a relationship with the City Hall themselves, while only one local collaboration relationship is mentioned by the representative of the City Hall (

Figure 4). This unbalanced perspective might indicate that the local public authorities are not aware of their real role within the local tourism network. However, the representative of the local public administration indicated their openness for constantly collaborating with all the local stakeholders, mentioning that invitations are made periodically for all of them to participate in public meetings and consultations.

In terms of external relationships, the balanced distribution of collaborators from all geographical contexts is an advantage. Recent collaboration relationships with the local public administration in two destinations from the regional context, Campulung Moldovenesc and Gura Humorului, were indicated as the main ones that envisage collective benefits for the entire destination. As such, the three destinations were brought together by the geographical proximity and by the fact that all of them belong to the same historical region, Bucovina, which is a brand itself. The stated purpose of the collaboration is that of taking advantage of the complementary assets of the three destinations in order to provide integrated tourism products and to promote together the entire region.