A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cruise Service Quality

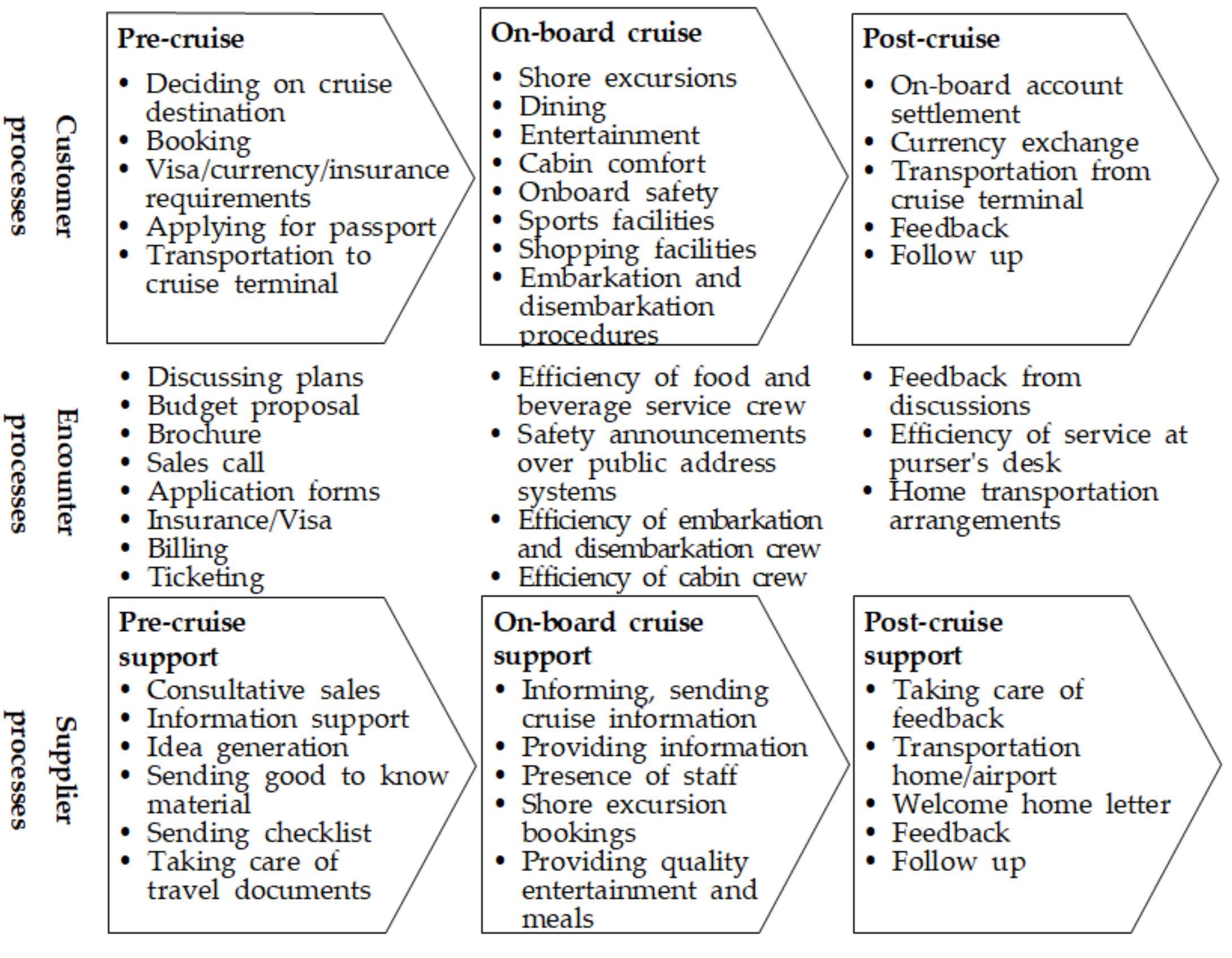

2.2. Cruise Service Attributes

3. Method

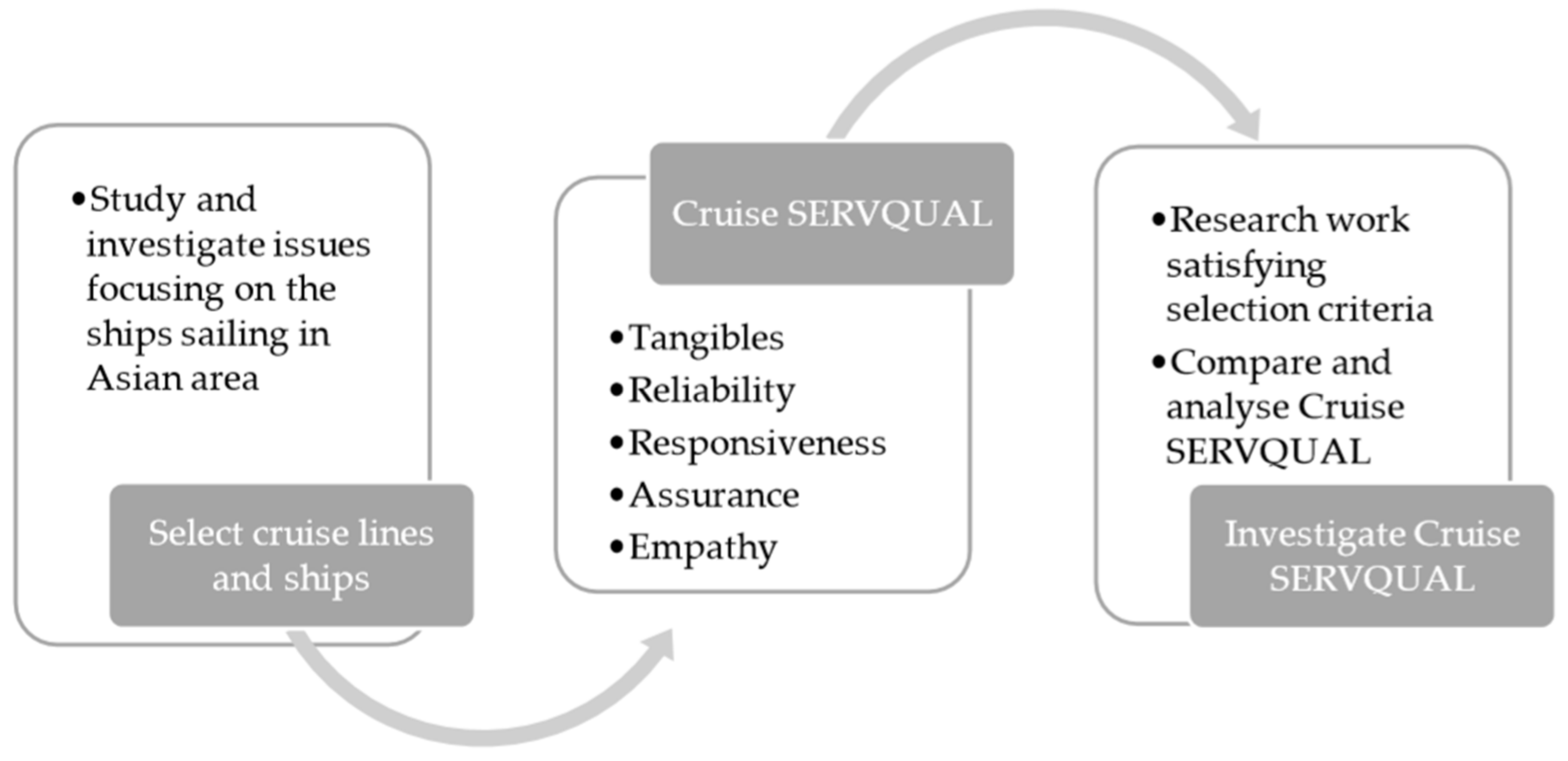

3.1. Research Flowchart

3.2. Objectives and Method

4. Result

4.1. Cruise SERVQUAL

4.2. Cruise SERVQUAL Investigation

4.2.1. Tangibles

4.2.2. Reliability

4.2.3. Responsiveness

4.2.4. Assurance

4.2.5. Empathy

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papathanassis, A. The growth and development of the cruise sector: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Nijkamp, P. Itinerary planning: Modelling cruise lines’ lengths of stay in ports. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Market Watch Website. Available online: https://cruisemarketwatch.com/growth (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- CLIA. 2018 Asia Cruise Industry Ocean Source Market Report; Cruise Line International Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- CLIA. 2019 Asia Cruise Deployment & Capacity Report; Cruise Line International Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bake, D.A. Exploring Cruise Passengers’ Demographics, Experience, and Satisfaction with Cruising the Western Caribbean. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Rev. 2015, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Identifying antecedents and consequences of well-being: The case of cruise passengers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.; Lee, S.; Goh, B.; Han, H. Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. The effect of gamification on psychological and behavioral outcomes: Implications for cruise tourism destinations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Petrick, J.F. Examining the antecedents of brand loyalty from an investment model perspective. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A.; Beckmann, I. Assessing the ‘Poverty of cruise theory’ Hypothesis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. In search of ‘a research front’ in cruise tourism studies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, L.J. Cruise Tourists’ Perceptions of Destination: Exploring Push and Pull Motivational Factors in the Decision to Take a Cruise Vacation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.R.; Petrick, J.F. Towards an Integrative Model of Loyalty Formation: The Role of Quality and Value. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. The Roles of Quality, Value, and Satisfaction in Predicting Cruise Passengers’ Behavioral Intentions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monferrer, D.; Segarra, J.R.; Estrada, M.; Moliner, M.Á. Service Quality and Customer Loyalty in a Post-Crisis Context. Prediction-Oriented Modeling to Enhance the Particular Importance of a Social and Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, T. The structure of customer satisfaction with cruise-line services: An empirical investigation based on online word of mouth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, K.R. The Role of Social Media in Crisis Management at Carnival Cruise Line. J. Bus. Case Stud. JBCS 2014, 10, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, C.S. Carnival cruise lines: Charting a new brand course. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2006, 47, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. The two market leaders in ocean cruising and corporate sustainability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwortnik, R.J. Shipscape influence on the leisure cruise experience. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2008, 2, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L.; Lekakou, M.; Stefanidaki, E. Cruise and container shipping companies: A comparative analysis of sustainable development goals through environmental sustainability disclosure. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A. Cruise tourism management: State of the art. Tour. Rev. 2020, 72, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Schlesinger, W. The sustainability of cruise tourism onshore: The impact of crowding on visitors’ satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, L. Reconsidering global mobility–distancing from mass cruise tourism in the aftermath of COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Schmidt, S.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Karampournioti, E.; Labenz, F. Measuring brand performance in the cruise industry: Brand experiences and sustainability orientation as basis for value creation. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2017, 23, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könnölä, K.; Kangas, K.; Seppälä, K.; Mäkelä, M.; Lehtonen, T. Considering sustainability in cruise vessel design and construction based on existing sustainability certification systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Lines International Association. 2020 State of the Cruise Industry Outlook; Cruise Line International Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 1–25. Available online: https://cruising.org/news-and-research/research/2019/december/state-of-the-cruise-industry-outlook-2020 (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Tong, H. The Labor Market of Chinese Cruise Seafarers: Demand, Opportunities and Challenges. Marit. Technol. Res. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retiling 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Holland, S.; Han, H. A Structural Model for Examining how Destination Image, Perceived Value, and Service Quality Affect Destination Loyalty: A Case Study of Orlando. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 15, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanic, D.C.; Drew Rosen, L. Measuring service quality in restaurants: An application of the SERVQUAL instrument. Hosp. Res. J. 1994, 18, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F.; Ryan, C. Analysing Service Quality in the Hospitality Industry Using the SERVQUAL Model. Serv. Ind. J. 1991, 11, 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimensions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. Taiwanese tourists’ perceptions of service quality on outbound guided package tours: A qualitative examination of the SERVQUAL dimensions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frochot, J.; Hughes, H. HISTOQUAL: The development of a historic houses assessment scale Isabelle. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. ECOSERV: Ecotourists’ Quality Expectations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J.; Snaith, T. From SERVQUAL to HOLSAT: Holiday satisfaction in Varadero, Cuba. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. Customer response to intangible and tangible service factors. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.C. Enhancing luxury cruise liner operators’ competitive advantage: A study aimed at improving customer loyalty and future patronage. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. Segmenting Cruise Passengers with Perceived Reputation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Day, J.; Cai, L.A. Exploring Tourist Perceived Value: An Investigation of Asian Cruise Tourists’ Travel Experience. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2014, 15, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Mohr, L.A. Critical Service Encounters: The Employee’s Viewpoint. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.A.; Berry, L.L. The Combined Effects of the Physical Environment and Employee Behavior on Customer Perception of Restaurant Service Quality. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggett, M.; Lim, W.M. Service Quality and the Cruise Industry. In The Business and Management of Ocean Cruise; Vogel, M., Papathanassis, A., Wolber, B., Eds.; CABI International: London, UK, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Petrick, J.F.; Tonner, C.; Quinn, C. The utilization of critical incident technique to examine cruise passengers repurchase intentions. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Line International Association. Available online: http://www.akcruise.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/2011-CLIA-Lifestyle-Trends-Survey.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Xie, J.H.; Kerstetter, D.L.; Mattila, A.S. The attributes of a cruise ship that influence the decision making of cruisers and potential cruisers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. Using case studies in research. Manag. Res. News 2002, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Olsen, L.S.; Karlsdóttir, A. Sustainability and cruise tourism in the arctic: Stakeholder perspectives from Ísafjörður, Iceland and Qaqortoq, Greenland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leposa, N. Problematic blue growth: A thematic synthesis of social sustainability problems related to growth in the marine and coastal tourism. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A. Prospective case study design: Qualitative method for deductive theory testing. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Case study Research: Design and Method, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cruise Industry News. Asia-Pacific Market Briefing. Available online: https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/store2/product/2014-2015-asia-pacific-market-briefing/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Esser, F.; Vliegenthart, R. Comparative Research Methods. Int. Encycl. Commun. Res. Methods 2017, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Crociere. Available online: https://www.costacruises.eu/fleet.html (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Princess Cruises. Available online: https://www.princess.com/ships-and-experience/ships/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Star Cruises. Available online: https://www.starcruises.com/kr/en/ships (accessed on 25 January 2017).

- Vogel, M. Pricing and Revenue Management for Cruises. In The Business and Management of Ocean Cruise; Vogel, M., Papathanassis, A., Wolber, B., Eds.; CABI International: London, UK, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- CDC Vessel Sanitation Program. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/vsp/default.htm (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Nakazawa, E.; Ino, H.; Akabayashi, A. Chronology of COVID-19 cases on the Diamond Princess cruise ship and ethical considerations: A report from Japan. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Hanaoka, S.; Kawasaki, T. The cruise industry and the COVID-19 outbreak. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC: CDC’s Role in Helping Cruise Ship Travelers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/cruise-ship/what-cdc-is-doing.html (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Costa Crociere Careers. Available online: https://career.costacrociere.it/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Princess Cruises Careers. Available online: https://www.princess.com/careers/ (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Star Cruises Careers. Available online: https://www.starcruises.com/us/en/careers (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Cruise Minus. Available online: https://www.cruiseminus.com (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- CruiseCritic: Solving Cruise Problems: Onboard. Available online: https://www.cruisecritic.com/articles.cfm?ID=84 (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy: COVID-19 Cruise Ship Studies Reflect Unique Disease Traits. Available online: https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2020/06/covid-19-cruise-ship-studies-reflect-unique-disease-traits (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Hung, K.; Lee, J.S.; Wang, S.; Petrick, J.F. Constraints to cruising across cultures and time. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa Concordia Disaster. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Concordia_disaster (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Cruise Law News. Available online: https://www.cruiselawnews.com (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- CruiseCritic: Help! My Luggage Is Lost. What Should I Do? Available online: https://www.cruisecritic.com/articles.cfm?ID=3940 (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- IMO Safety Regulation: Passenger Ship. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Regulations/Pages/PassengerShips.aspx (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Castillo-Manzano, J.I.; López-Valpuesta, L. What does cruise passengers’ satisfaction depend on? Does size really matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Verification of the role of the experiential value of luxury cruises in terms of price premium. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österman, C.; Hult, C.; Praetorius, G. Occupational safety and health for service crew on passenger ships. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Hernández-Perlines, F.; Giorgi, G. Connected at sea: The influence of the internet and online communication on the well-being and life satisfaction of cruise ship employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y.; Hyun, S.S. Roles of passengers’ engagement memory and two-way communication in the premium price and information cost perceptions of a luxury cruise. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential effects on Chinese citizens’ lifestyle and travel. Tour. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Contents |

|---|---|

| Tangibles | Physical facilities, equipment, and appearance of personnel |

| Reliability | Ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately |

| Responsiveness | Willingness to help customers and provide prompt service |

| Assurance | Knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire trust and confidence |

| Empathy | Caring, individualized attention the firm provides its customers |

| Dimensions | Cruise SERVQUAL | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tangibles | ① Ship Facts: Cruise ship’s facilities have up-to-date equipment. | [10,14,15,21,30,41,52] |

| ② Ship’s interior style, cabin, cleanness: Cruise ship’s facilities are visually appealing. | ||

| ③ Crew members’ appearance: Crew members are well-dressed and appear neat. | ||

| ④ Service materials, other cruise guests: The appearance of the physical facilities of cruise ship is in keeping with the type of services provided. | ||

| Reliability | ① Itinerary and departure/arrival time compliance: When the cruise ship promises to do something by a certain time, it does so. | [13,15,30,41,42,43,49,52] |

| ② When customers have problems, the cruise ship is sympathetic and reassuring. | ||

| ③ Cruise ship is dependable. | ||

| ④ Cruise onboard programs are on time: Cruise ship provides its services at the time it promises to do so. | ||

| ⑤ Cruise ship keeps its records accurately. | ||

| Responsiveness | ① They do not tell customers exactly when services will be performed. | [13,14,21,30,41,43,49,52] |

| ② You do not receive prompt service from crew members. | ||

| ③ Crew members are not always willing to help customers. | ||

| ④ Crew members are too busy to respond to customer requests promptly. | ||

| Assurance | ① Customers can trust crew members. | [8,13,30,41,43,49,52] |

| ② Announcements for safety and lifeboat drills: Customers feel safe in their transactions with crew members. | ||

| ③ Crew members are polite. | ||

| ④ Crew members get adequate support from cruise lines to do their jobs well. | ||

| Empathy | ① These cruise lines do not give customers individual attention. | [13,30,41,42,43,49,52] |

| ② Crew members of cruise lines do not give customers personal attention. | ||

| ③ Crew members of cruise lines do not know what customer’s needs are. | ||

| ④ These cruise lines do not have customer’s best interests at heart. | ||

| ⑤ These cruise lines do not have operating hours convenient to all their customers. |

| Quality Item | Costa Victoria | Diamond Princess | Superstar Virgo | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship Facts Year built Renovation Shipbuilder Passengers (Max) Crew Gross Tonnage Length Beam No. of cabins No. of deck PSR Facilities Restaurants Sports Spa Bar/Lounge/Theatre Others | 1996 2013 Bremer Vulkan 2394 790 75,166 828 feet (252 m) 105 feet (32.2 m) 964 14 decks (12 for guest use) 31.4–39 5 restaurants 3 pools, Gym, Spa, Solarium 10 bars, Casino, theatre Reception, Shore excursion office, Medical centre, Internet café, Shop, etc. | 2004 2014 Mitsubishi 2706 1100 115,875 952 feet (290.2 m) 123 feet (37.5 m) 1337 18 decks (13 for guest use) 35.7–42.8 9 restaurants 4 pools, Gym, Spa, Solarium 5 bars, Casino, Theatre Reception, Shore excursion office, Medical centre, Internet café, Shop, Library | 1996 2012 Meyer Werft 2800 1300 75,338 881 feet (268.6 m) 106 feet (32.3 m) 935 13 decks (10 for guest use) 26.9–38 9 restaurants 2 pools, Gym, Spa, Solarium 5 bars, Casino, Theatre Reception, Shore excursion office, Medical centre, Karaoke, Shop, etc. | ∙The cruise ships sailing in Asia area are old. ∙Costa Victoria is the oldest ship among all Costa ships. ∙Lack of Jumbo cruise ships with diverse entertainment facilities was revealed. ∙Ship renovations were made recently, so facilities’ functions are diversified (2012–2013). |

| ∙Interior style ∙Cabin ∙Cleanness (CDC) | Elegant Italian Style 14–45 m2 96 | Modern Premium Style 15.6–123.5 m2 98 | Splendid Asian Style 12–60 m2 Not Yet Inspected | ∙Cruise line’s concepts and interiors style are matched with target customers. ∙Regular controls are needed with Vessel Sanitation Program (CDC score). |

| Crew members’ appearance (attire) | Uniform and nametag | Uniform and nametag | Uniform and nametag | Crew members are monitored for the regulation of attire and appearance. |

| ∙Service materials ∙Other customers | Seapass Card, Daily program, etc. European, Asian (Chinese) | Seapass Card, Daily program, etc. Oceanian, Asian (Japanese), North American | Seapass Card, Daily program, etc. Asian (Chinese, Singaporean, Indian) | Service materials are in keeping with the types, concepts, atmosphere of services provided. |

| Quality Item | Costa Victoria | Diamond Princess | Superstar Virgo | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itinerary and Departure/Arrival time compliance | They can change the itinerary and onboard program; they only refund in case of changes because of cruise line’s one-sided reasons providing substitutive services/compensation | Same | Same | Not liable for changing itineraries and onboard programs; they usually provide substitutive services or compensations for customer satisfaction case by case |

| When customers have problems, the cruise ship is sympathetic and reassuring | Passenger–Crew ratio (PCR) (2.8:1) | PCR (2.5:1) Handling of various incidents | PCR (2.2:1) | The attitudes for solving customer problems affect a cruise line’s reputation |

| Cruise ship is dependable | ∙Europe No.1 Cruise ∙For more than 65 years the historic Costa Cruises brand has been providing the best of Italian hospitality. ∙Costa Concordia disaster; Rescue of passengers from a fishing boat on fire | ∙Premium cruise with innovative ships, an array of onboard options, and an environment of exceptional customer service ∙Norovirus, COVID-19 | ∙The Leading Cruise Line in the Asia Pacific ∙Star Cruises has built its reputation on offering first-rate Asian hospitality throughout its fleet of six vessels ∙No accidents | The cruise line’s reputation is not just because of ship fires, Concordia-like disasters; continuous records about environmental pollution, mistreatment of crew members, PR response and follow-up reactions |

| Cruise onboard programs on time | Announcements for daily schedules and programs | Announcements for daily schedules and programs | Announcements for daily schedules and programs | Facilities opening and program operation on time |

| Cruise ship keeps its records accurately | Handling of Personal data (ID information, reservation information-cabin categories, membership, additional services, shore excursions, purchases (invoice)) | Same | Same | Cruise ships keep personal records (Id, reservations, purchases) accurately |

| Quality Item | Costa Victoria | Diamond Princess | Superstar Virgo | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∙They do not tell customers exactly when services will be performed (-) | ∙No time assurance for baggage delivery | ∙Same as Costa | ∙Check-in baggage delivery to the cabins no later than 60 min after sailing | ∙They do not tell customers exactly when check-in/out and baggage delivery services will be performed and finished |

| ∙You do not receive prompt service from crew members (-) | ∙Receipts issued promptly after purchasing on board | ∙Same | ∙Same | ∙Immediate reaction after customer requests |

| ∙Refund immediately after cancellation purchasing | ||||

| ∙Crew members are not always willing to help customers (-) | ∙PCR (2.8:1) | ∙PCR (2.5:1) | ∙PCR (2.2:1) | ∙Spontaneous customer support |

| ∙Improving PCR ratio | ||||

| ∙Crew members are too busy to respond to customer requests promptly (-) | ∙24-h Front office service (room service-nominal fee/free) | ∙24-h Front office service (room service-nominal fee) | ∙24-h Front office service (room service-nominal fee) | ∙Stand ready for customers 24 h |

| ∙Interactive TV, Kiosk, Princess@sea | ∙Smart web service |

| Quality Item | Costa Victoria | Diamond Princess | Superstar Virgo | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∙Customers can trust crew members | ∙Costa Concordia accident | ∙No navigation related accidents | ∙No navigation related accidents | ∙The records of accidents and safe rescue cases |

| ∙Burning fishing boat rescue | ∙Emergency patient transportation | |||

| ∙Announcements for safety and lifeboat drills | ∙All crew members have BST (Basic Safety Training) | ∙Same | ∙Same | ∙Announcements for safety through onboard broadcasting |

| ∙Regular lifeboat drills | ∙Regular lifeboat drills | |||

| ∙Crew members are polite | ∙Guest Satisfaction Questionnaire | ∙C.R.U.I.S.E. program | ∙Guest Feedback Form | ∙Service improvement through guests’ feedback |

| ∙Crew members get adequate support from cruise lines to do jobs well | ∙Onboard training only | ∙Same as Costa | ∙GSTA (Genting-Star Tourism Academy) | ∙Training—Cruise service experts have job requirements and communication skills |

| Quality Item | Costa Victoria | Diamond Princess | Superstar Virgo | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cruise lines do not give customers individual attention (−) | 24-h room service (nominal charge/free) | 24-h room service (free) | 24-h room service (nominal fee) | Stand ready for customer’s needs 24 h a day |

| Membership (6 levels) | Membership (6 levels) | Membership (5 levels) | Membership: customer relationship management | |

| Crew members do not give customers personal attention (-) | 5 dining options | 13 dining options | 4 dining options | Several dining options, though open hours of onboard facilities are limited |

| Anytime dining | ||||

| Crew members do not know what customers’ needs are (-) | Special dining request | Same as Costa | Shore excursion option | Consider the customer’s individual dining request and shore excursion selection |

| Shore excursion option | ||||

| Cruise lines do not have customer’s best interests at heart (-) | Membership (6 levels) benefits | Membership (4 levels) benefits | Membership (5 levels) benefits | Provide benefits through cruise membership and next cruise promotion |

| Cruise fare promotion | Next cruise promotion | Casino membership promotion | ||

| Cruise lines do not have operating hours convenient for all their customers (-) | Charter/group guests caring | Charter/group guests caring | Group guests caring | Respond to special requests, understanding customer’s specifics |

| Tipping (Adult: USD 12.00, 4–14: 50%, 0–3: Free) | Tipping (USD 14.50) | No tipping policy | Tipping policy |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, Y.; Cha, K.C. A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198073

Yoon Y, Cha KC. A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198073

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Yeohyun, and Kyoung Cheon Cha. 2020. "A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198073

APA StyleYoon, Y., & Cha, K. C. (2020). A Qualitative Review of Cruise Service Quality: Case Studies from Asia. Sustainability, 12(19), 8073. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198073