1. Introduction

Child abuse is as old as humanity. The current definition of child abuse did not emerge until the 1970s, however. Throughout history there have been many cases, but understanding of the phenomenon has changed.

Settling on a single definition is complicated. We can focus on the one provided by the World Health Organization: “Any form of physical and/or emotional abuse, sexual abuse, neglect or inconsiderate treatment, or commercial or other exploitation that causes a real or potential harm to the health, survival, development or dignity of the child in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power,” [

1] (p. 9).

We also find different perspectives referring to their typology. Lau et al. [

2] proposed a Hierarchical Classification System (SCJ) model, whereby the abuse’s concept is dichotomous (yes/no), differentiating between active and passive abuse, and when both take place, the active forms are considered the predominant type of abuse within the established hierarchy of sexual abuse, physical abuse, child neglect and emotional abuse. On the other hand, there is the Modified Maltreatment Classification System (SCMM) proposed by English et al. [

3]. It is part of the model initially proposed by Barnett et al. [

4], and its classification is as following: physical abuse, sexual abuse, child neglect, emotional abuse and moral/legal/educational abuse. Currently, one of the most widely accepted hierarchies is that provided by the Childhood Observatory [

5]: physical abuse, negligence, emotional abuse and sexual abuse.

In every child abuse situation, there is a victim and an aggressor. We could define as child abuse’s victims, as indicated by the United Nations Children’s Fund, “Those children and adolescents up to 18 years old who suffer occasional or habitual acts of physical, sexual or emotional violence, whether in a family group or in social institutions”, [

6] (p. 2). Child abuse, in addition to producing consequences at the time, can have negative effects in adulthood, including psychological, emotional, behavioral and neurobiological consequences [

1,

7,

8].

The cases currently detected are only a small part of those that take place. The ignorance in society means that it is often suggested that child abuse only takes place in marginal populations, but it is a social problem that concerns everyone. Worldwide, child abuse is legal in many cases. In more than 100 countries, children in schools suffer violent punishment authorized by the State [

9]. The World Report on violence against boys and girls includes international data and indicates that only 2.4% of children in the world are protected against child abuse [

10]. Around 300 million of two- to four-year-old children (three out of four) are routinely subjected to violence by their caretakers; one in four adults believe that violence is necessary to raise children [

11].

In Spain, the Ministry of Social Rights and 2030 Agenda [

12], through “Childhood in Data”, collects the most relevant data related to the situation of children in the country. In relation to the population under 18 years old, it pointed out that in 2018, the latest year for which such data are available, there were 6532 cases of child abuse in Spain. The cases have been increasing with respect to previous years. In 2017 there were 6038 cases. In 2014 the number of cases was significantly lower, at 4674 cases. Several studies suggest that it is very difficult to know the real figures. Pereda points out that “the percentages vary according to the sex of the victim and the origin of the sample analyzed, although they place this experience between a 10 and 20% of the community population” [

13] (p. 132).

In recent years child abuse has become more visible. More and more action protocols and prevention plans are being developed. Even so, there is a part of the population that is not aware of this problem. Save the Children [

14], in a national study on the importance of violence against children, found that 65.2% of the population described it as a very serious social problem, 25.5% as a serious social problem, 3.9% as a minor social problem, 2% did not consider it a social problem and 3.4% of the population found it better not to answer. If these data are extrapolated to the Spanish population, with a population of almost 47 million inhabitants, that would mean that more than two and a half million inhabitants do not consider it as a social problem, or consider it not very relevant.

This large number of people who do not consider it a relevant social problem may be due to various reasons related to previous experiences and erroneous beliefs [

15], such as the belief that each family is free to raise their children as they wish and therefore that no person should meddle in the privacy of another family. It can also be due to previous negative experiences wherein appropriate reporting did not lead to the desired or expected resolution. Another reason may be the erroneous belief that the reporting of a child abuse case must be accompanied by absolute evidence and certainty and/or fear of being wrong, and family members deciding to report the reporter or to excuse acts of mistreatment due to different beliefs, customs or cultural values.

If we take into account that at least 38 possible child abuse victims are detected every day within families in Spain [

16], and data collected in research indicate that teachers rarely detect cases, the need for action in the educational context is clear. Schools are the most important socializing context after the family. When underage children do not receive the necessary attention, “schools have a greater importance, because it is there where they establish the affective bonds that they cannot develop in their family environment” [

17] (p. 103).

Schools must address the issue of child abuse. This is reflected in our country’s law [

18]. Educational centers have the obligation to keep confidential the information they have about students and their families, except in cases where it is believed that the law is being broken, such as in cases of mistreatment, which must be reported to the appropriate authorities, and the students’ needs, especially those in disadvantaged situations, must be met by all educational centers with the help of public services.

In the Spanish education system, the ratio of students per teacher for the first cycle of Early Childhood Education (0–3 years old) is regulated by each autonomous community. However, for the second cycle of Early Childhood Education (3–6 years old) and for Primary Education (6–12 years old), the Ministry of Education sets the maximum number of students per classroom at 25. In many cases, this large number of children per teacher makes it challenging to attend to and care for each child individually with the attention they deserve. This makes it difficult for teachers to detect and act on cases of child abuse among their students.

Several studies have been carried out to consider the training that educational professionals have with regard to child abuse. Carrion [

19], after his research with a sample of 26 teachers belonging to the Early Childhood Education and Primary Education stage, found that 42.3% of teachers recognize that they did not have adequate knowledge of the subject.

Another research question is whether teachers have received any training on child abuse during their professional careers. Several investigations indicate that the majority of teachers have never received any training in this area. In one study, 93% of 33 teachers surveyed [

20] and 85% of 274 professionals [

21] answered negatively, confirming the lack of training that teachers receive on child abuse.

Prieto [

22], with data from 420 teachers, found that 38.3% of teachers have come across a case of child abuse, and almost a quarter of them admit not having acted. This data on the insufficiency of detection of child abuse is confirmed by another study of 79 teachers, in which 75.9% said they had never detected any cases. Despite this, the vast majority (88.3%) wanted to improve their training [

23].

One study [

24] indicates that it cannot be confirmed that having more experience helps to identify cases of child abuse. However, according to the data collected in the study, the more years of experience teachers have, the more they agree that teachers have the right knowledge and know the procedure to follow in cases of child abuse.

All these data are consistent with the low rate of cases detected by school teachers (6.25%). Another 6.25% of cases are detected by health center pediatricians, 25% by emergency room doctors and 62.5% by nurses [

25]. Despite these percentages, which show a low level of detection in education, it has been shown that teachers in the early educational stages are the best placed people for detection.

Most education professionals have a positive predisposition to change the situation. This is corroborated by a study in which 99% of 221 teachers surveyed stated that child abuse could be prevented, and 98.64% of them wanted to receive training [

26]. Some educators noted that in order to improve the situation with regard to child abuse, it is necessary to introduce appropriate skills into the training curricula of universities on a compulsory basis [

27].

Having established the prevalence of victims of child abuse and the fundamental role played by early-education teachers in the prevention and detection of child abuse, this study considers the following research issue: Do the teachers of Early Childhood Education and Primary Education, both in training and in service, have the necessary knowledge about child abuse and how to act on it? Therefore, this study focuses on analyzing these teachers’ knowledge of child abuse and how to respond to it, and their interest in improving responses to child abuse. In addition, this study investigates the training they have received in this area and whether cases have been found during their professional practice, and it determines the differences between teachers in training and those in service.

3. Results

The results of the questionnaire on child abuse by teachers are presented below. To this end, this section shows a comparison between in-service and in-training teachers regarding previous training, the detection and intervention in child abuses cases, and the knowledge, the action and the improvement aspects in the face of child abuse. Finally, the three variables’ data (knowledge, action and improvement aspects) are analyzed together to check if there is a relationship between them.

3.1. Results of the Previous Training in Child Abuse among Teachers

Analyzing the teachers’ responses to their training with regard to child abuse, it was found that 29.2% of 144 teachers in training and 28.7% of 80 teachers in service stated that they had received some form of training. Through the performance of the Chi-square test it was found that these differences are not significant (p = 0.95), so having received some type of training on child abuse is independent of being a teacher in training or in service.

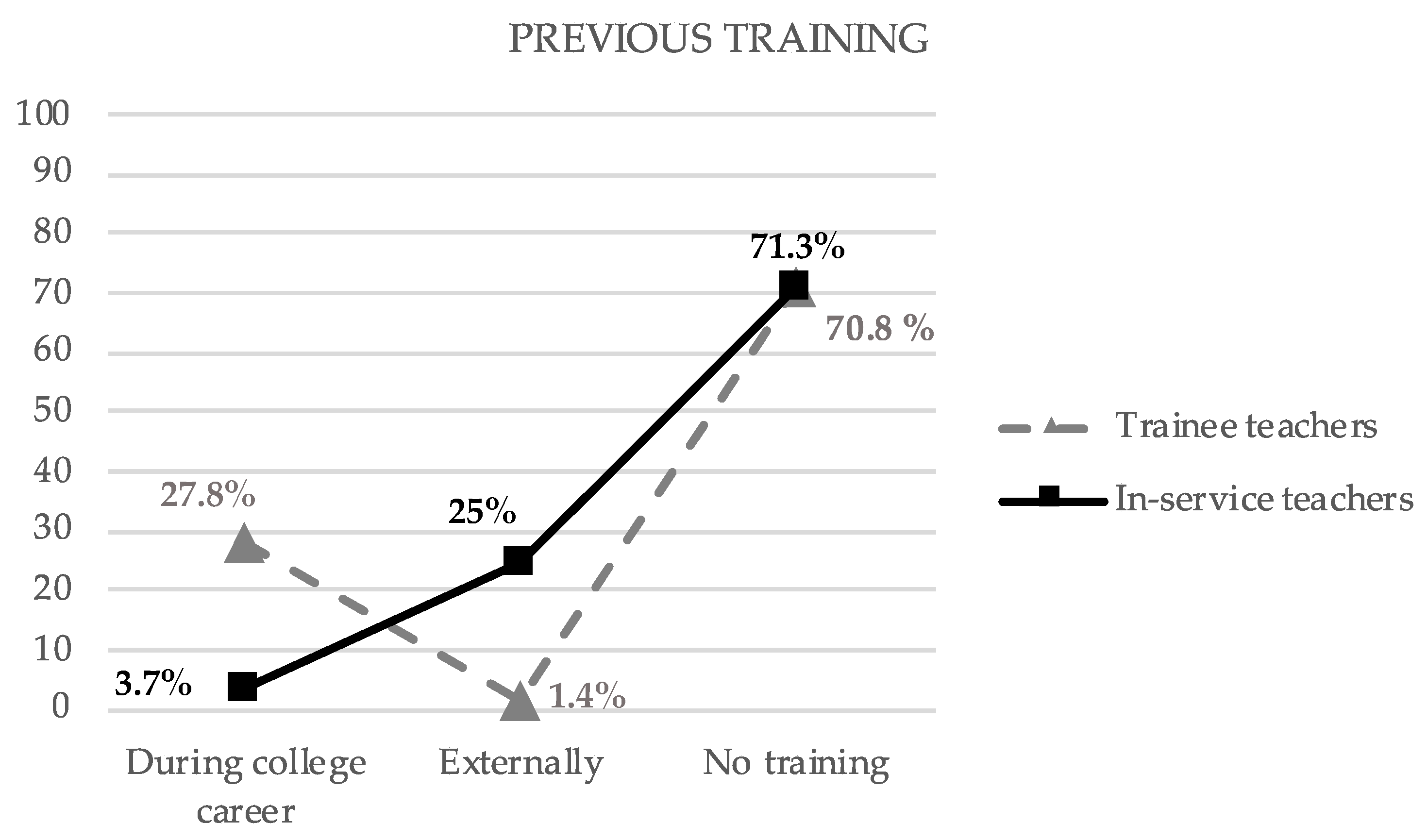

Of the teachers in training who have received some type of training, 27.8% of teachers received it during their university degree and 1.4% of teachers received it externally. However, of in-service teachers who have received training, only 3.7% received it during their university degree and 25% received it externally.

The Chi-square test indicates that there is a significant association (

χ2(2) = 44.66,

p < 0.05) in the form the training was received in with respect to the stage teachers are at in their careers (in training or in service). If we look at the descriptors (

Table 2), we can observe how trainee teachers have received more training during their university studies, since of the 42 teachers in training who indicated having received training, 40 indicated having received it during their degree. On the other hand, out of 23 in-service teachers who reported having received training, only three indicated having received it during their university degree. However, the training received externally was higher for in-service teachers than for trainee teachers, with 20 in-service teachers reporting having received the training externally, compared to two teachers in training.

Figure 1 shows the differences in the training received with regard to child abuse between teachers in service and teachers in training, showing the percentages according to the way in which they have received the training (externally or during their university degree), as well as those who have not received any type of training.

3.2. Results of Detection and Action in Child Abuse’s Cases among Teachers

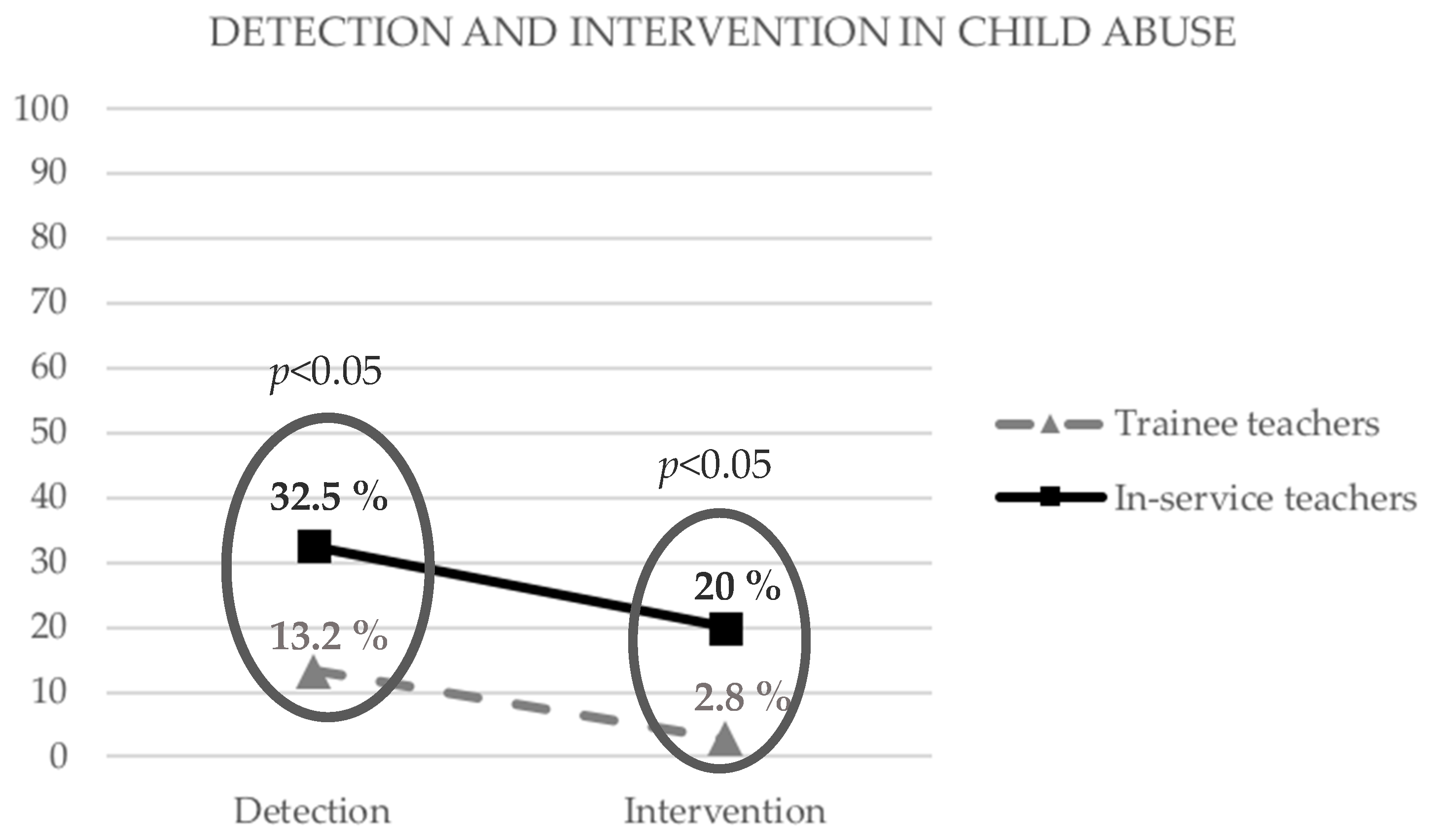

Regarding the detection of child abuse cases, taking into account the total number of teachers in training who participated (144), 19 answered they had detected some cases (13.2%), while 125 answered they had not detected any case (86.8%). However, among active teachers, 26 responded positively (32.5%) and 54 responded negatively (67.5%) to the question of whether they had ever come across cases of child abuse. As might be expected, in-service teachers detected more child abuse cases than trainee teachers. Through the Chi-square test we were able to verify that the differences between teachers in training and teachers in service in the detection of child abuse cases perceived in the classroom are statistically significant (χ2(1) = 11.94, p < 0.05).

As far as cases of intervention are concerned, it was also possible to observe through the Chi-square test that there are significant differences between the teachers in service and the teachers in training (χ2(1) = 18.759, p < 0.05). A greater number of teachers in service (20%) stated that they had intervened in child abuse cases, while only 2.8% of teachers in training stated that they had acted in any intervention. This means that detection and intervention increase when the teachers are in service and therefore spend more hours with students.

Figure 2 shows the differences in the detection of and intervention in child abuse cases between trainee teachers and in-service teachers, showing the percentages of affirmative responses of having detected and intervened in child abuse cases during their professional experience.

3.3. Results of Knowledge and Action against Child Abuse among Teachers

The general knowledge scale about child abuse consists of 10 items and allows one to obtain a score between 0 and 10 points. Therefore, the highest score (10 point) corresponds to an excellent knowledge level about child abuse.

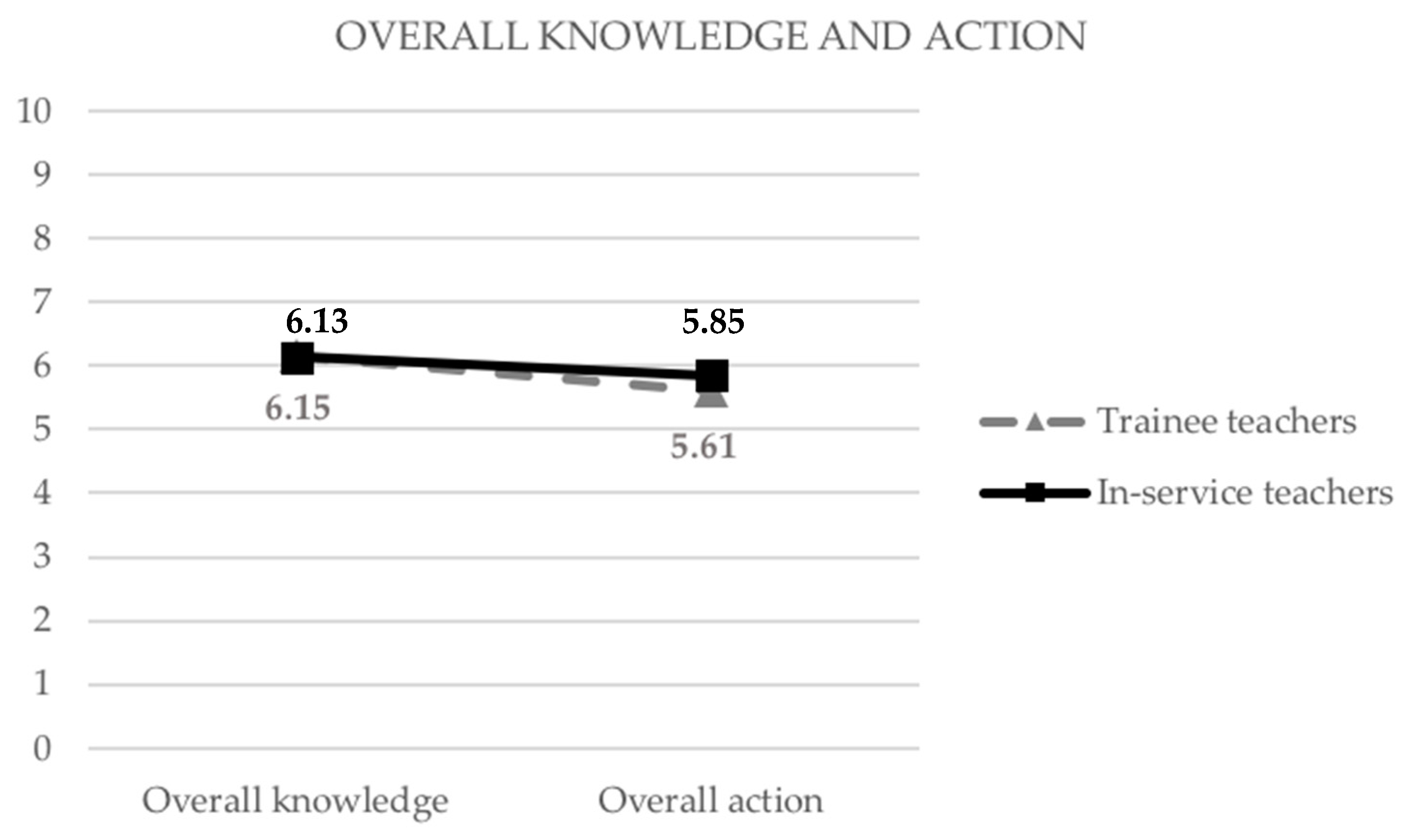

The graph in

Figure 3 shows that for the variable of global knowledge of child abuse, teachers in training (

M = 6.15) have obtained a higher average score than teachers in service (

M = 6.13), there being a small difference in the results. After carrying out the Student

t-Test for independent samples, it was verified that there are no statistically significant differences (

p = 0.11) in the knowledge of child abuse between teachers in training (

M = 6.15,

ST = 1.47) and teachers in service (

M = 6.13,

ST = 1.76).

The knowledge level on child abuse action was also measured through a scale with 10 items, allowing us to obtain a score between 0 and 10. The highest score corresponds to 10, meaning that teachers have a high knowledge level about acting on child abuse.

The results show that there are no major differences in knowledge of action in child abuse between teachers in training and teachers in service.

Figure 3 shows that the average level of knowledge about child abuse action between teachers in training (

M = 5.61) is slightly lower than that which teachers in service have (

M = 5.85). Through the Student

t-Test for independent samples, it was verified that these differences are not statistically significant (

p = 0.35) with regard to knowledge about child abuse action among teachers in training (

M = 5.61,

ST = 1.87) and those in service (

M = 5.85,

ST = 1.79).

Therefore, in

Table 3 it can be observed that the level of knowledge of both child abuse and the correct action to take is independent of being a trainee teacher or an in-service teacher. Both have an intermediate knowledge, as their average scores oscillate between 5.30 and 6.30 points.

3.4. Results of Aspects for Improvement in the Face of Child Abuse among Teachers

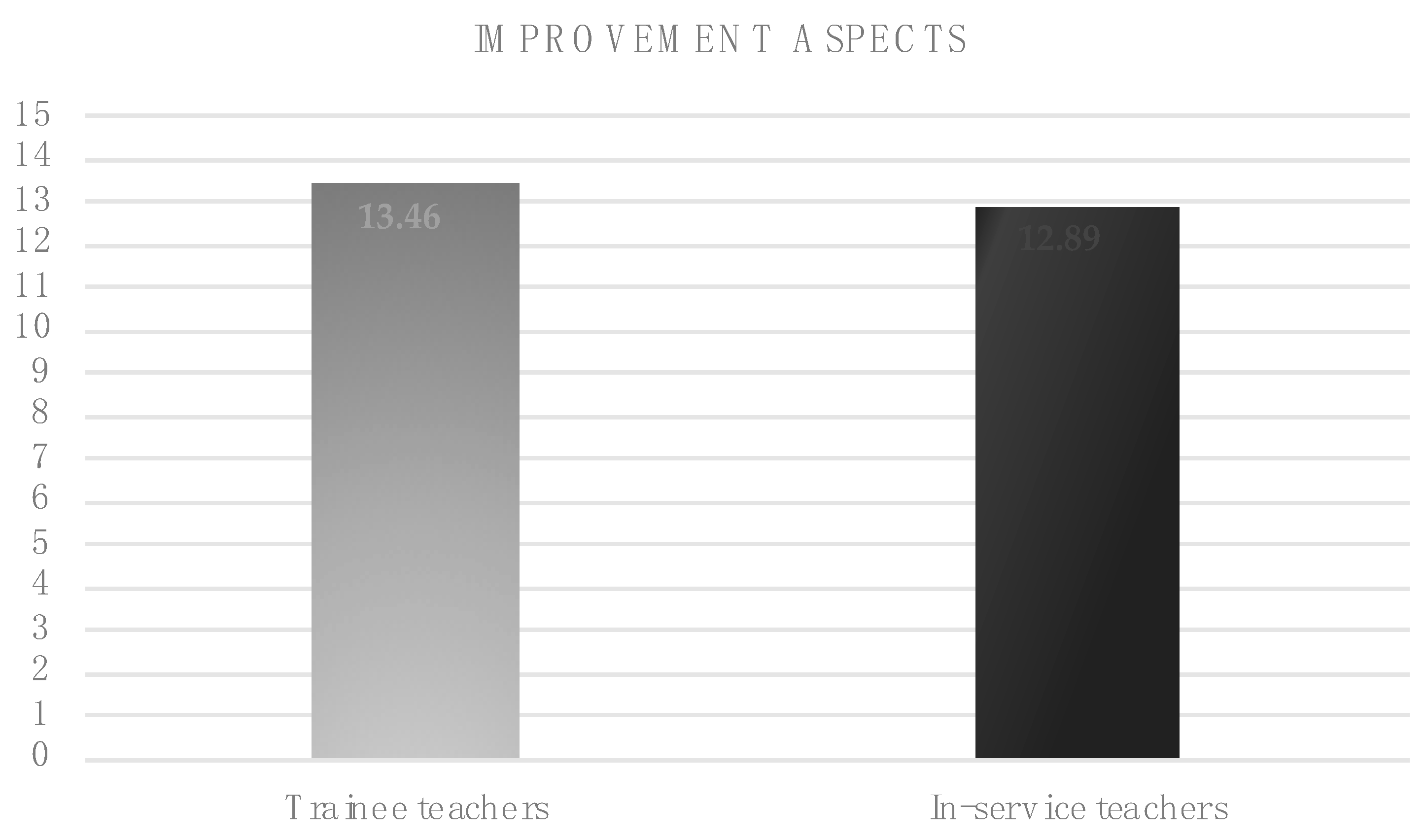

In order to evaluate teachers’ intentions to improve in relation to child abuse, a 5-item scale was proposed, scored from 0 to 3. Therefore, the score that teachers can obtain on this scale is between 0 and 15 points.

Figure 4 shows the average scores presented by teachers in training and teachers in service with reference to the issues raised relating to aspects for improvement in child abuse. These results show that the trainee teachers’ average (

M = 13.46) is higher than the in-service teachers’ average (

M = 12.89). However, both figures are quite high and show a high level of interest among teachers in making improvements in relation to child abuse.

Through the Student

t-Test for independent samples, it was possible to verify in

Table 4 that there are statistically significant differences (

t(143,17) = 2.01,

p < 0.05,

r = 0.16) in the aspects for improvement in relation to child abuse between teachers in training (

M = 13.46,

ST = 1.84) and teachers in service (

M = 12.89,

ST = 2.15), with the former presenting a higher level of interest.

Finally, teachers were asked about the relevance and lack of awareness of child abuse in education through the following question: “In a personal way, describe how important you think training and knowledge about familial child abuse is for teachers today. Is it a relevant issue in teaching? Is it something unknown in this profession?” With this, the aim was to check the participants’ views on how child abuse is currently affecting teaching and whether it is given enough importance.

The different points of view expressed by teachers in training and teachers in service are outlined below. Among the trainee teachers’ answers we can highlight the following:

- -

“Because it is a complicated issue it is omitted and, therefore, not studied at universities. However, it is something that, unfortunately, we will find in classrooms and we must know how to act in these situations and how it will affect the child...” (Trainee teacher studying Primary Education, 21 years old).

- -

“Unfortunately, the teachers did not tell us anything about this issue”. (Trainee teacher studying Primary Education, 24 years old).

- -

“I think it is a very relevant issue in teaching, but unfortunately very little is known about this. I consider that one of the problems is that in the teachers’ university training it is not emphasised or given too much relevance”. (Trainee teacher studying Primary Education, 23 years old).

Among the teachers in service, the vast majority point out that it is difficult to address this issue and that training could be improved. We can highlight their following answers:

- -

“Unfortunately, this is not unknown to those of us who work in education, but there are so many training needs and in so many areas that we are sometimes overwhelmed”. (In-service teacher in Primary Education, 45 years old; 20 years experience).

- -

“In my opinion, teacher training in child abuse is clearly insufficient in the vast majority of cases. However, I consider it essential to know the indicators and the way to act in case of suspicion of child abuse, knowing that schools are an essential detections area”. (In-service teacher in Early Childhood Education, 27 years old; 5 years experience).

- -

“It’s a quite unknown aspect of teaching, but I think it’s very important for the child’s emotional development. The administration should train us to detect cases”. (In-service teacher in Early Childhood Education, 59 years old; 35 years experience).

As can be seen, many of the teachers agree that it is a very important issue, yet unknown in the educational field, and they show a high level of interest in better training. Unfortunately, a great number of participants report that they are not well prepared to detect and act in those situations.

3.5. Results of the Relationship between Knowledge, Action and Aspects for Improvement in Child Abuse among Teachers

Finally, the relationship between the three main research variables was considered, pertaining to knowledge of child abuse, action and aspects for improvement. To this end, the Pearson’s Correlation was carried out, as is shown in

Table 5.

To begin with, we were able to verify that there is a statistically significant and positive relationship between general knowledge and teachers’ action in child abuse cases (r = 0.42, p < 0.01). This indicates that the more knowledge about child abuse a teacher has, the more knowledge about action to take the teacher has as well.

We can also verify that there is a statistically significant and positive relationship, although weaker, between the total knowledge of child abuse and the improvement measures proposed by teachers (r = 0.19, p < 0.01).

Finally, it can be observed that there is also a statistically significant, positive and weak relationship between teachers’ knowledge of child abuse intervention and aspects for improvement in this area (r = 0.15, p ≤ 0.05).

With the results obtained from the Pearson’s Correlation, we can affirm that there is a significant and positive relationship between the three variables studied, these being global knowledge, global action and aspects for improvement in child abuse. That is, having a greater global knowledge about child abuse is also related to having a greater knowledge about how to act in cases of child abuse, and to having a higher level of interest in establishing improvement measures.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In the Early Childhood Education and Primary Education stages, pupils, being very young, are often not able to express their feelings and problems in their families. On the other hand, pupils spend long school days with the same classmates and teachers. As such, teachers have a fundamental role in the detection of child abuse and in taking appropriate action to help the child.

The data from this research have confirmed that teachers have an intermediate level of knowledge of child abuse, but at the same time they show great interest in training and improvement.

The obtained results show that there are no significant differences between the training received by trainee teachers and by teachers in service. A high number of participants, more than 70%, confessed to not having received any type of training. These data, although more encouraging, corroborate the results of the study by Díaz et al. [

20], whereby 93% of those surveyed stated that they had not received any training. Arenas’ research [

21] also confirms these results, since 85% of teachers reported the same answer, i.e., that they had never received training. In addition, there are differences in the way in which teachers have acquired this training, with more in-service teachers receiving it externally and more trainee teachers receiving it during their university education. This may be due to the fact that Spain has improved university training in education on this issue. Despite this, many argued that it is an issue that should be addressed even more. However, the majority of in-service teachers did not receive training during their studies, and in order to become informed they have had to seek it through their own means externally. This is probably due to the fact that today students receive more training in this problem at university, compared to the small number of in-service teachers who received it during their university period and, therefore, had to be trained externally. In spite of this data, we can affirm that there are no significant differences in knowledge of child abuse between teachers in training and teachers in service.

According to previous studies, 38.3% [

22] and 24.1% [

23] of teachers have detected cases of child abuse during their professional careers. These study results corroborate these data, because it has been observed that 32.5% of teachers in service have come across at least one case of child abuse in schools, and only 20% have intervened. On this occasion, we did find significant differences in cases of detection and intervention between teachers in training and those in service, possibly due to the greater number of hours the latter spend in schools. However, the data obtained about the knowledge of how to act in child abuse cases do not show significant differences.

All these data show the medium to low levels of knowledge about child abuse among a large percentage of teachers. This situation is worrying because, if teachers are not able to act, many students will suffer serious consequences that could be avoided with the early detection of cases. However, despite these negative figures, we have discovered in this research that there is a very high number of teachers (if not all of them) who are willing to improve their training. This high level of interest among teachers is also corroborated by Salinas and Campos’ [

26] research, where 98.64% of those who were surveyed wanted to receive training. According to Rúa et al. [

27], educators believe that it would be appropriate to improve training by introducing content on abuse into the curriculum. The fact is that teachers in training are more interested in improving this situation, as well as their knowledge, than teachers in service. These results could be due to the fact that teachers in training have more time and, therefore, can attend training events, extra talks during their studies, etc. However, teachers in service, due to their heavy workload, do not have the time they would like to have to be able to train in this area.

It is essential to know that teachers’ knowledge of child abuse will have an impact on their actions. This has been reflected in this research by verifying that there is a positive and significant relationship between knowledge, capacity for action, and the intention to establish improvement measures in the area of child abuse. That is, it is observed that there is a tendency among teachers who have greater general knowledge about child abuse to act and intervene more effectively, and to continue searching for proposals and solutions to improve in this area.

For future research, it would be interesting to design teacher training activities on child abuse and its detection and intervention in the classroom, checking their effectiveness through the instruments designed in this study to verify the impact of having an adequate knowledge about child abuse and its impact on students. Through these evaluation scales (Scale of knowledge of child abuse, Scale of action against child abuse, Scale of aspects for improvement in child abuse), it would be possible to verify the effectiveness of the training and to observe teachers’ progress in their knowledge about child abuse. This would be made possible by applying the questionnaire (Assessment instrument on child abuse to evaluate teachers) before and after training. That is, based on teachers’ results about their knowledge of child abuse, training sessions on this problem can be developed, and once these programs have been implemented, the questionnaire can be re-conducted to determine their improvement.

It would also be appropriate to move forward in the study of child abuse with another type of population and context, to contrast the differences that may exist between teachers from other countries and under different cultural and socio-economic conditions. Similarly, it would be useful to introduce new variables, such as teachers’ gender, age or years of experience, to observe whether there are differences in the detection of and intervention in cases of child abuse in the classroom between men and women, and according to their age and years of experience.

In addition, it would be appropriate to propose strategies within the education system to help students who are child abuse victims or have serious family problems. Considering the rate of child abuse in Spain and teachers’ medium to low knowledge about it, educational centers should implement appropriate training on child abuse, including detection and intervention, to enable pupils to receive assistance and to reduce the number of victims, without forgetting the relevant reporting to the appropriate agency according to the seriousness of each case.