Analysis of ASD Classrooms: Specialised Open Classrooms in the Community of Madrid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- General data about ASD classrooms;

- Physical characteristics of the classroom;

- General characteristics of the students;

- Relation ASD classroom/mainstream classroom;

- Relation ASD classroom/school/state;

- Teacher training for ASD classrooms;

- Conclusions and general overview.

3. Results

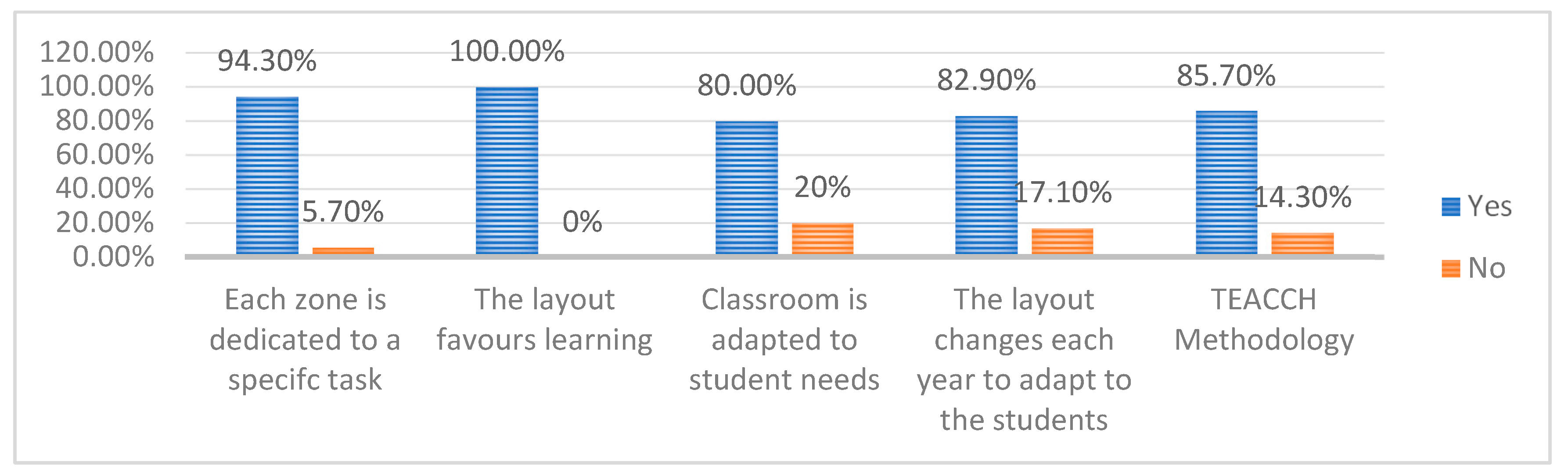

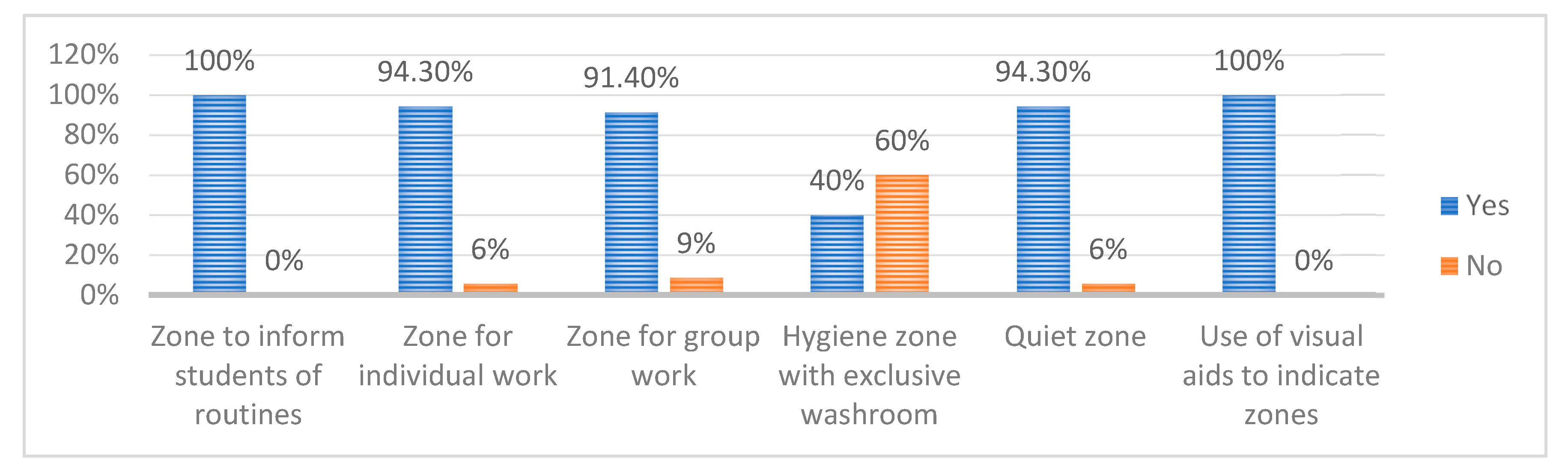

3.1. Layout and Organisation of ASD Classroom

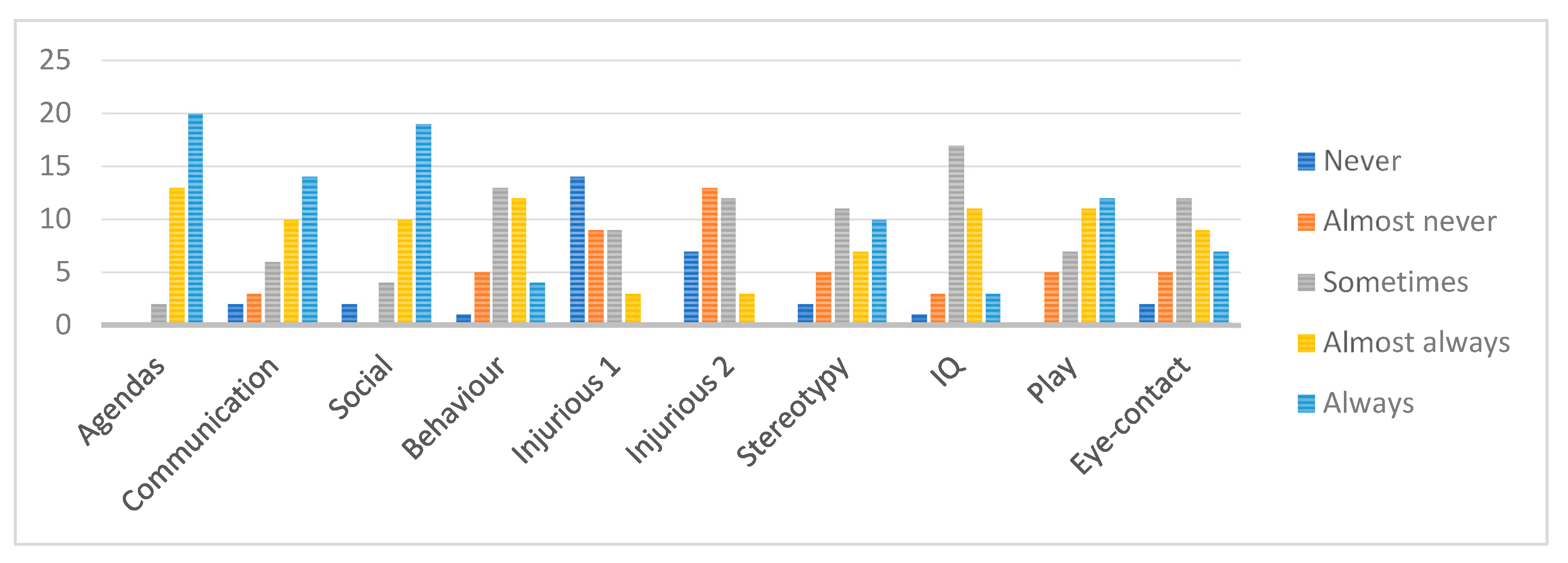

3.2. General Profile of ASD Students

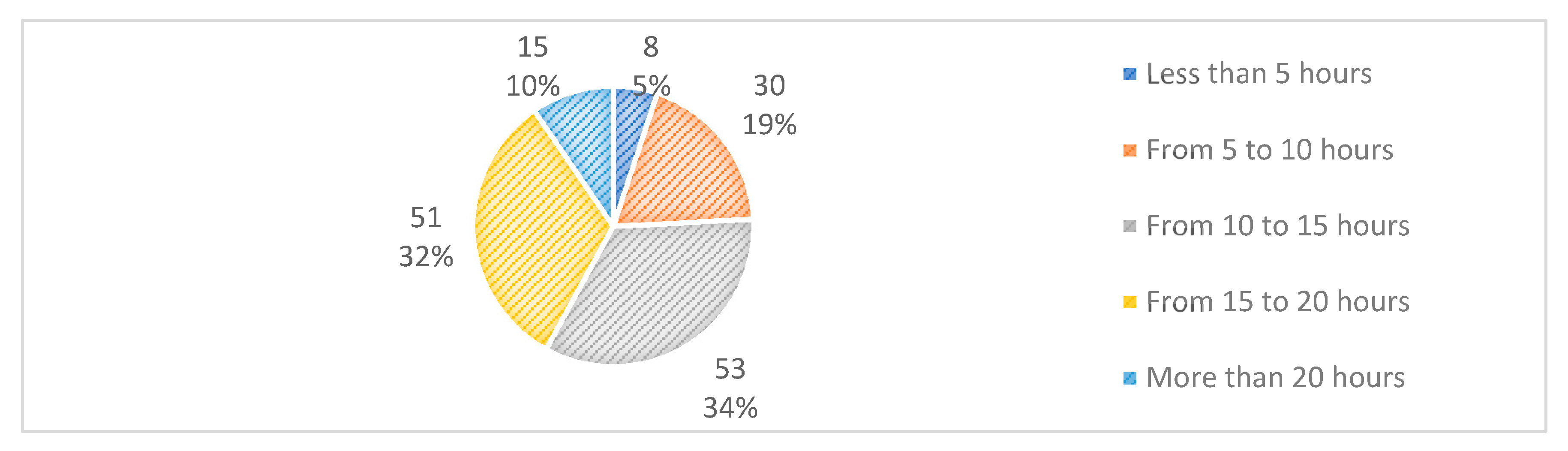

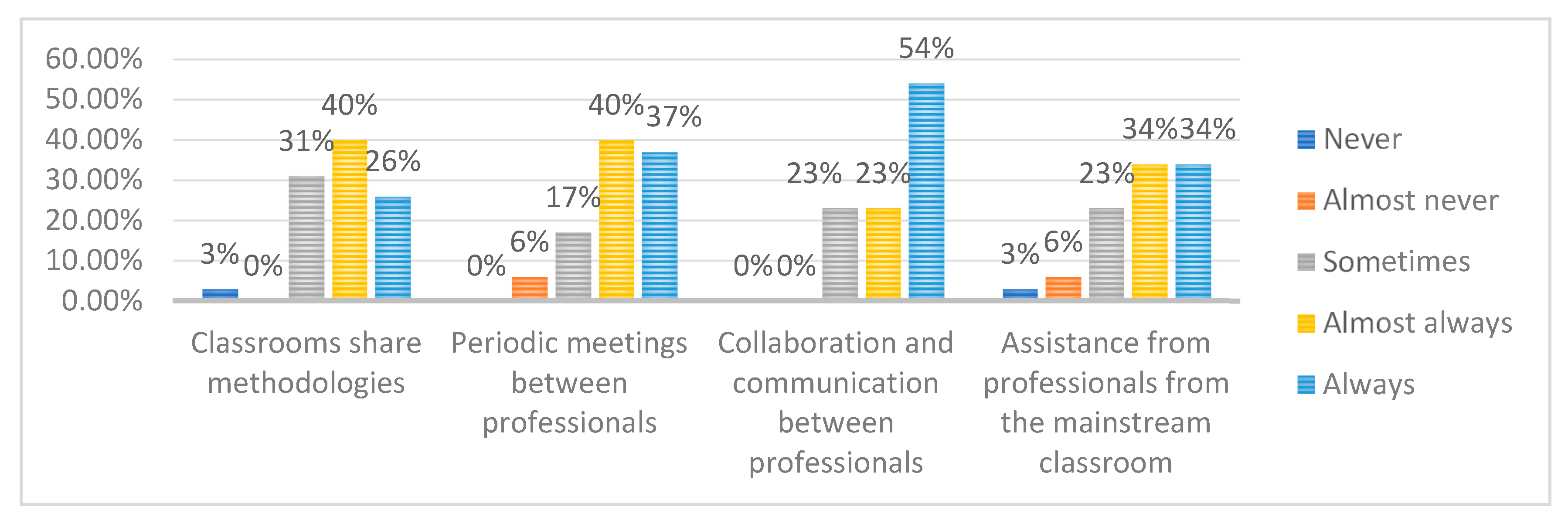

3.3. Relation between ASD Classroom and Mainstream Classroom

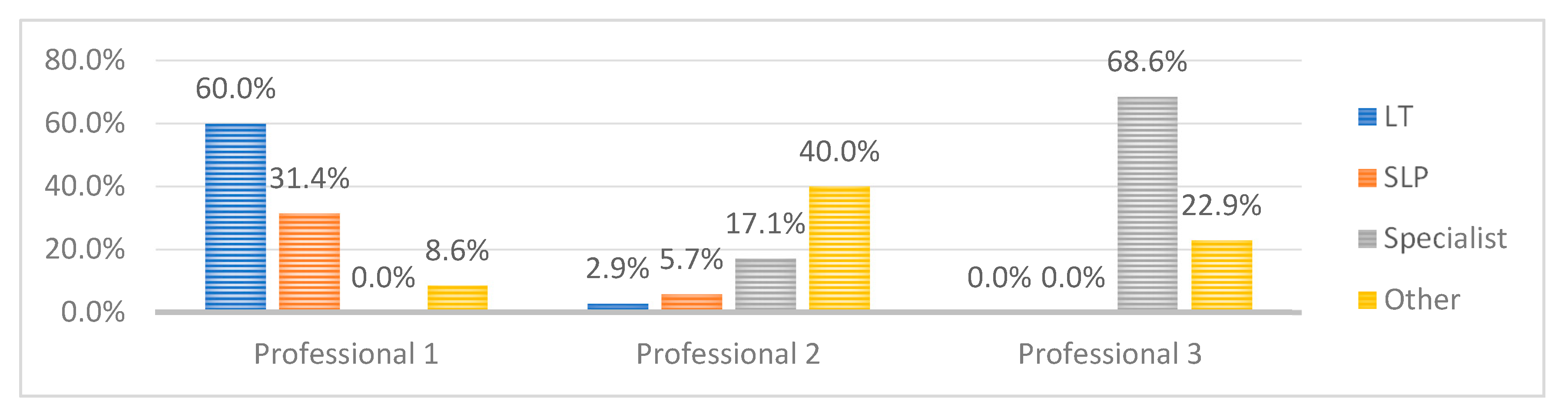

3.4. Collaboration and Assistance Received by ASD Classrooms

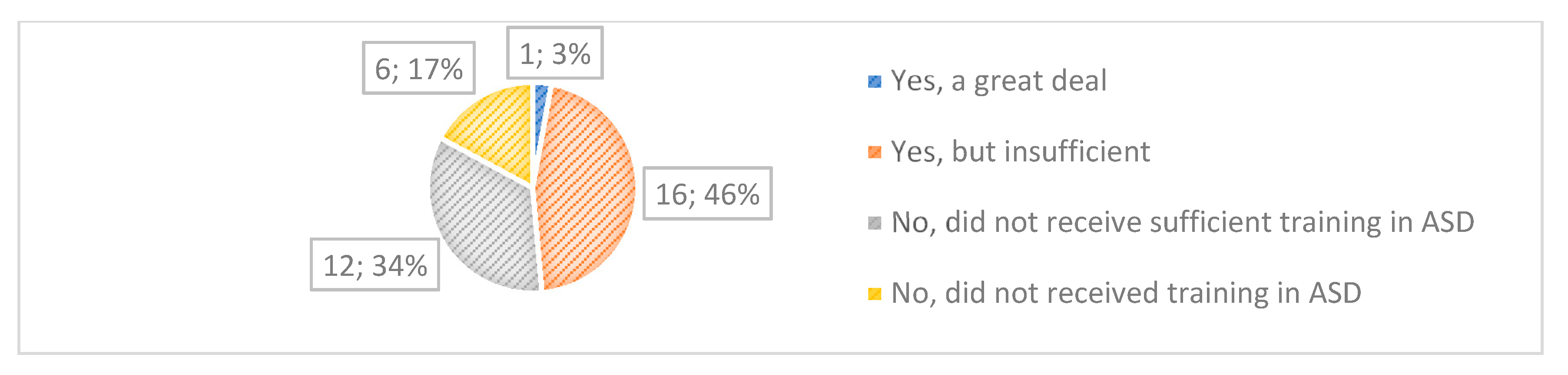

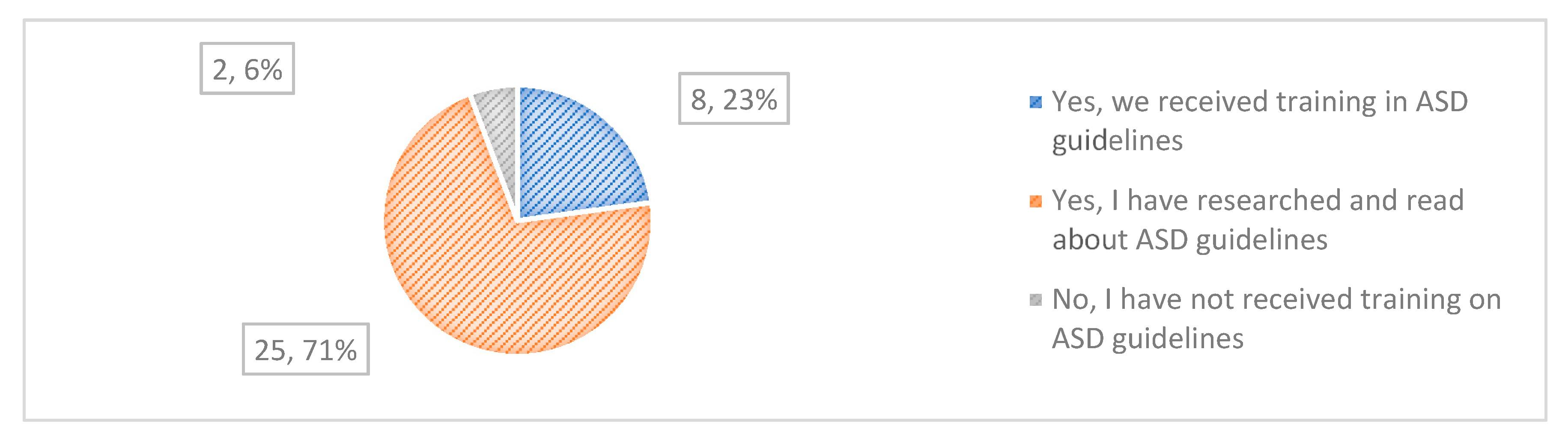

3.5. Teacher Training for ASD Classrooms

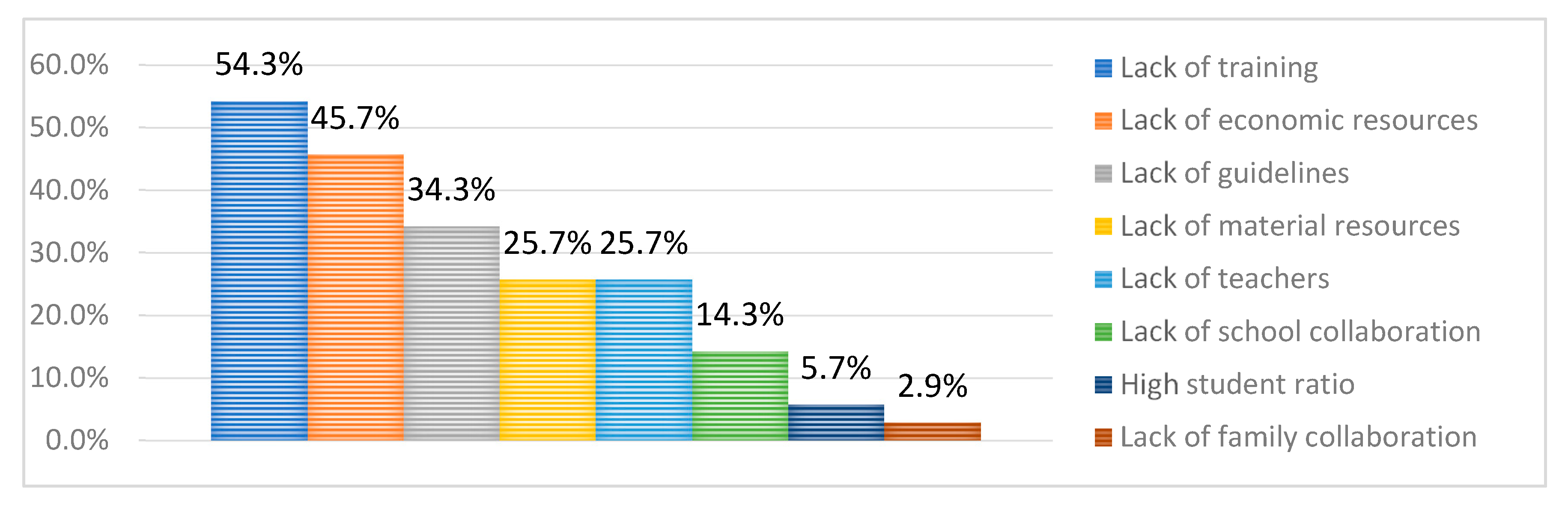

3.6. Benefits and Shortcomings of ASD Classrooms

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Are you an ASD teacher? Yes / No… |

|---|

| Type of centre: Public / Private / Charter school... |

| Academic course in which this classroom was created: __________. Existing educational stages: Pre-primary / Primary / Secondary. Number of ASD students in your current classroom: __________. Number of professionals and their title: _________. - Professional 1: LT / SLP / Teacher / Psychologist / Psycho-pedagogy/ Nurse / Physiotherapist /Technical. - Professional 2: LT / SLP / Teacher / Psychologist / Psycho-pedagogy/ Nurse / Physiotherapist /Technical. - Professional 3: LT / SLP / Teacher / Psychologist / Psycho-pedagogy/ Nurse / Physiotherapist /Technical. - Professional 4: LT / SLP / Teacher / Psychologist / Psycho-pedagogy/ Nurse / Physiotherapist /Technical. In case you are a public professional, what specialty did you choose at the beginning? ____________. Is there exist the “teacher in the shadow” role in the classroom or school? ____________. Number of students evaluated in the ASD classroom to go a Special School? ____________. Why they were evaluated? |

| PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ASD CLASSROOM. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||||||||

| Is there a specific area to report routines and activities? (Agendas, weekly and monthly calendars, etc.) | |||||||||||||

| Does the classroom have an area for individual work? | |||||||||||||

| Does the classroom have an exclusive area for group work? | |||||||||||||

| Is there a hygiene area with an exclusive toilet for the ASD classroom? | |||||||||||||

| Does it have a relaxing area? | |||||||||||||

| Is each zone dedicated to a specific activity? | |||||||||||||

| Do you use visual aids to inform on the distribution of the different areas? | |||||||||||||

| If so, please specify which ones: | |||||||||||||

| Do you consider that the distribution of your classroom encourages student learning? | |||||||||||||

| Justify your answer | |||||||||||||

| Do you consider that your classroom is adapted to your student’s needs? | |||||||||||||

| Justify your answer: | |||||||||||||

| Does the distribution of the classroom change each year according to the children´s characteristics? | |||||||||||||

| Do you use any type of methodology within the ASD classroom? | |||||||||||||

| If so, please specify which ones: | |||||||||||||

| Briefly describe the materials you use to work with children with ASD | |||||||||||||

| GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDENTS | |||||||||||||

| Answer the questions with a number from 1 to 5; where 1 is: No / never; 2: Hardly ever; 3: Sometimes; 4: Often; 5: Yes / always | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| Most of the children in the ASD classroom usually need routines and agendas to structure their time | |||||||||||||

| If so, indicate what type of agendas and / or routines: | |||||||||||||

| They usually need communication supports (for example: Boards, communication notebooks, visual aids, AAC, PECS, etc.) | |||||||||||||

| If so, indicate which ones: | |||||||||||||

| They usually present alterations in social interaction (for example: Inability to develop relationships with peers, lack of social or emotional reciprocity) | |||||||||||||

| Most have behavioural problems in two or more contexts | |||||||||||||

| They tend to present harmful behaviour towards themselves | |||||||||||||

| They tend to present harmful behaviour towards their classmates or other teachers | |||||||||||||

| Most of them present stereotyped behaviour such as hand washing, aligning objects, flapping ... | |||||||||||||

| If so, indicate some examples of stereotypical behaviour: | |||||||||||||

| The intellectual level is usually lower than the corresponding to their age | |||||||||||||

| They usually have difficulties in symbolic or imaginative play | |||||||||||||

| They tend not to have eye contact | |||||||||||||

| RELATIONSHIP ASD-CLASSROOM OF MAINSTREAM CLASSROOM | |||||||||||||

| Answer the questions with a number from 1 to 5; where 1 is: No / never; 2: Hardly ever; 3: Sometimes; 4: Often; 5: Yes / always | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| There is collaboration and fluid communication among the professionals in both classrooms | |||||||||||||

| The teachers in both classrooms hold regular meetings to monitor students with ASD | |||||||||||||

| The student usually spends more than half of his teaching day in the mainstream classroom | |||||||||||||

| Specify how many hours per week approximately each student spends in your mainstream classroom: - Student 1: _________ - Student 2: _________ - Student 3: _________ - Student 4: _________ - Student 5: _________ | |||||||||||||

| Every methodology used in the ASD classroom usually has continuity in the mainstream classroom (for example: Manipulative materials, study techniques, learning strategies, etc.) | |||||||||||||

| RELATIONSHIP AMONG THE ASD CLASSROOM -EDUCATIONAL CENTER-STATE | |||||||||||||

| Rate your satisfaction level from 1 to 5 with the following factors, being 1 “not at all satisfied” and 5 “very satisfied” | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| Collaboration and help from the ordinary teachers to the ASD classroom. | |||||||||||||

| Collaboration and help from part of the educational community: Material resources, regulations, support for families, regular meetings with the management team, etc. | |||||||||||||

| Collaboration and help from Autism specific associations: Trainings on ASD, regular visits, fluid communication, etc. | |||||||||||||

| Collaboration and help from the families of the children in the ASD classroom | |||||||||||||

| Collaboration and help from the Community of Madrid: Regulations, legislation, etc. | |||||||||||||

| ASD CLASSROOM TEACHER TRAINING Do you consider the knowledge acquired at university is useful for your work in the ASD classroom? ○ Yes, definitely. ○ Yes, but it is not enough ○ No, I received training on Attention to Diversity, but it was not enough ○ No, I did not receive any training about this topic. ○ Others: ________________________________________________________________ | |||||||||||||

| Have you continued training in autism since you left college? ○ Yes, I usually attend educational courses and conferences ○ Yes, but less than I would like ○ No, but I would like ○ No, I don’t think it’s necessary Do you know the regulations proposed by your Autonomous Community on the operation of ASD classrooms? ○ Yes, we have received training on it ○ Yes, I have researched and read about it ○ Yes, but I don’t think it’s useful ○ No, you have not received this regulation ○ No, my Autonomous Community does not have a regulation ○ Others: ________________________________________________________________ CONCLUSIONS AND GENERAL VIEW What benefits of the ASD Classrooms do you consider most important for the education of the students? You can check up to three options: ○ Personalized attention ○ Specialized teacher training on ASD ○ Adaptation of the environment ○ Visual supports ○ Less sensory stimulation (smells, sounds, etc.) ○ Lower ratio ○ Inclusion of students in their mainstream classroom ○ Material resources ○ Others: ____________________________________________________________________ What disadvantages of the TEA Classrooms do you consider most important for the education of the students? You can check up to three options. ○ Little training of the TEA classroom teachers ○ Few economic resources ○ Few material resources ○ Little collaboration from other professionals at the centre ○ Little collaboration from families ○ A unified standard for TEA classrooms throughout the community ○ Few teachers ○ Others: ___________________________________________________________________ If you had to transmit to the Community of Madrid an improvement proposal to help all TEA classrooms, what would it be? | |||||||||||||

References

- Arnaiz, P. La Educación Inclusiva en el Siglo XXI: Avances y Desafíos. In Proceedings of the Master Lecture Read at the Academic Act of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 28 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, 4th ed.; Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, 5th ed.; Médica Panamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg, H. Defining language phenotypes in autism. Clin. Neurosci. Res. 2006, 6, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, S.; Szatmari, P.; Boyle, M.; Hanna, S.; Duku, E.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Investigating phenotypic heterogeneity in children with autism spectrum disorder: A factor mixture modelling approach. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiker, D.; Lotspeich, L.; Dimiceli, S.; Myers, R.; Risch, N. Behavioural phenotypic variation in autism multiplex families: Evidence for a continuous severity gradient. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 114, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, L.; Di Filippo, T.; Roccella, M. The child with Autism Disorder s (ASDS): Behavioural and neurobiological aspects. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2015, 31, 1187. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniowiecka-Kowalnik, B.; Nowakowska, B.A. Genetics and epigenetics of autism spectrum disorder—Current evidence in the field. J. Appl. Genet. 2019, 60, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölte, S.; Girdler, S.; Marschik, P.B. The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1275–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, R. Los Trastornos Generales del Desarrollo. Una Aproximación Desde la Práctica; Consejería de Educación, Dirección General de Participación y Solidaridad en la Educación: Sevilla, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, B.F.M.; Brewer, R.; Bird, G.; Catmur, C. Theory of mind is not theory of emotion: A cautionary note on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S.; McConnell, F.; Manola, E.; McConachie, H. Interventions based on the Theory of Mind cognitive model for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, M. Evolution in the Understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder: Historical Perspective. Indian J. Paediatr. 2017, 84, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, J.; Llorente, M. El niño al Que se le Olvidó Cómo Mirar; La Esfera de los Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Consejería de Educación. Los Centros de Escolarización Preferente Para Alumnado con Trastornos Generalizados del Desarrollo en la Comunidad de Madrid; Consejería de Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. La educación inclusiva, el camino hacia el futuro. In Proceedings of the Conferencia Internacional de Educación, Ginebra, Switzerland, 25–28 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shmuksky, S.; Gobbo, K. Autism Spectrum in the College Classroom: Strategies for instructors. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2013, 37, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández del Mazo, P.; Lozano, A.C.; Barrero, M.; de la Concha, F.; Olmo, L. Proyecto Educativo de Atención Integral Para Alumnado con TEA en Castilla la Mancha; FACLM: Castilla La Mancha, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- García, A. Puesta en Marcha de un aula TEA en un Centro Ordinario. Bachelor´s Thesis, Universidad de Segovia, Segovia, España, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, C.L. Classroom Design for Living and Learning with Autism; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heredero, E.; Zurita, M.; Gómez, L.M.; Alemany, R.; Medina, N. Análisis del proceso de diagnóstico y elaboración de una adaptación curricular: Estudio de casos. Rev. Ibero Am. Estud. Educ. 2012, 7, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, B.; Martín, E.; Pérez, E.M. La valoración de las aulas TEA en la Educación Infantil: La voz de docentes y familias. Univ. Salamanca Siglo Cero 2018, 49, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Morrier, M.J.; Hess, K.L.; Heflin, L.J. Teacher Training for Implementation of Teaching Strategies for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2014, 34, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Leppert, T. Brief Report: Outcomes of a Teacher Training Program for Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona, L.L.; Christodulu, K.V.; Rinaldi, M.L. Investigation of School Professionals’ Self-Efficacy for Working with Students with ASD: Impact of Prior Experience, Knowledge, and Training. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2017, 19, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauderdale-Littin, S.; Brennan, M. Evidence-Based Practices in the public school: The role of preservice teacher training. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2018, 10, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcallister, K. The ASD Friendly Classroom—Design Complexity, Challenge and Characteristics. In Proceedings of the Design Research Society International Conference 2010, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mesibov, G.B.; Shea, V. Structured Teaching and Environmental Supports. In Learners on the Autism Spectrum: Preparing Highly Qualified Educators; Dunn, K., Wolfberg, P., Eds.; Autism Asperger Publishing Co.: Minnetonka, MN, USA, 2008; pp. 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kidder, J.E.; McDonnell, A.P. Visual Aids for Positive Behaviour Support of Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Young Except. Child. 2017, 20, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnahan, C.R.; Hume, K.; Clarke, L.; Borders, C. Using Structured Work Systems to promote independence and engagement for students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Teach. Except. Child. 2009, 41, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesibov, G.B.; Shea, V.; Schopler, E. Structured Teaching. In The Teacch Approach to Autism Spectrum Disorders; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fein, D.; Dunn, M.A. Autism in Your Classroom: A General Educator’s Guide to Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders; Woodbine House: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire, P.K.; Hourcade, J. Teaching play skills to children with Autism Using Visually Structured Tasks. Teach. Except. Child. 2014, 46, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.M.; Ingersoll, B.R. Improving Social Skills in Adolescents and Adults with Autism and Severe to Profound Intellectual Disability: A Review of the Literature. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasari, C.; Dean, M.; Kretzmann, M.; Shih, W.; Orlich, F.; Whitney, R.; Landa, R.; Lord, C.; King, B.H. Children with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: A randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 57, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, E.; Chandler, S.; Baird, G.; Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A.; Loucas, T.; Charman, T. The experience of friendship, victimization and bullying in children with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with child characteristics and school placement. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Larraceleta, A.; González, A.; Cuesta, M.A.; Melendi, R.M.; Mónico, P.; Vázquez, A.; Fregeneda, P.; Hevia, L.; Iglesias, A.I.; et al. Orientaciones para planificar la respuesta educativa. In Propuesta Inclusiva para Intervenir en Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria; Consejería de Educación del Principado de Asturias: Asturias, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M. Aba en el tratamiento educativo. In Psyciencia; 2018; Available online: https://pavlov.psyciencia.com/2018/02/aba-tratamiento-autismo.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2019).

- Kim, J.; Cavaretta, N.; Ferting, K. Supporting preschool children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and their families. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Prof. 2014, 2014, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, N.; Eisenhower, A.; Carter, A.S.; Blacher, J. Satisfaction with Individualized Education Programs among Parents of Young Children with ASD. Except. Child. 2018, 84, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenbacher, S.L. Building Bridges: A Case Study of the Perceptions of Parents of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Towards Family/School Partnerships. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Chodiman, R.; Pooley, J.; Cohen, L.; Taylor, M. Students with ASD in Mainstream Primary Education Settings: Teachers’ Experiences in Western Australian Classrooms. Australas. J. Spec. Educ. 2012, 36, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Schumacher, S. Investigación Educativa, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Adison Wesley: Madrid, España, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A. Intervención a Través del Método TEACCH en un Alumno con Trastorno del Espectro del Autismo. Bachelor´s Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, V. Pensadores visuales en nuestras aulas: Métodos de intervención. Acercamiento al Método TEACCH. In Proceedings of the IX Jornadas de formación ASPRODIQ, Castilla la Mancha, Castilla la Mancha, Spain, 25–26 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, I. Efectividad de la Metodología TEACCH con el Alumnado TEA: Estudio de Revisión. Bachelor´s Thesis, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, A.; Rueda, I. Alteraciones de conducta en los trastornos del espectro autista. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 66, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, A. Relación Entre los Distintos Contextos Educativos Entre sí y con la Familia en Sujetos con TEA. Bachelor´s Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Extremadura, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval, M. La colaboración y la formación del profesorado como factores fundamentales para promover una educación sin exclusiones. Contextos Educ. Rev. Educ. 2008, 11, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, R.M.; Orellana, M.D. Actitudes de los docentes hacia la inclusión escolar de niños con autismo. Kill. Soc. 2018, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.; Sánchez, A.; Pastor, J.C.; Martínez, J. La formación docente ante el trastorno del espectro autista. Rev. Euroam. Cienc. Deporte 2019, 11, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vela Llauradó, E.; Martín Martínez, L.; Martín Cruz, I. Analysis of ASD Classrooms: Specialised Open Classrooms in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187342

Vela Llauradó E, Martín Martínez L, Martín Cruz I. Analysis of ASD Classrooms: Specialised Open Classrooms in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187342

Chicago/Turabian StyleVela Llauradó, Esther, Laura Martín Martínez, and Inés Martín Cruz. 2020. "Analysis of ASD Classrooms: Specialised Open Classrooms in the Community of Madrid" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187342

APA StyleVela Llauradó, E., Martín Martínez, L., & Martín Cruz, I. (2020). Analysis of ASD Classrooms: Specialised Open Classrooms in the Community of Madrid. Sustainability, 12(18), 7342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187342