Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions

Abstract

1. Introduction: Towards Entrepreneurial Organisation

2. Entrepreneurial Competencies Driving Organisational Change

2.1. From Entrepreneurial Universities to Entrepreneurial Competencies

2.2. Framework for Assessing Entrepreneurial Competencies

3. Case Study Overview

3.1. Research Design, Questions, and Target Group

- 1.

- How are the entrepreneurial competencies assessed in a (higher education) organisation?

- 1.1

- How do the employees evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation?

- 1.2.

- How do the supervisors evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their organisation?

- 1.3.

- Are there any differences between the employees’ and supervisors’ evaluations of their organization’s entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.

- How do personnel self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.1.

- How do the employees self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.2.

- How do the supervisors self-evaluate their entrepreneurial competencies?

- 2.3.

- Are there any differences between the employees’ and the supervisors’ self-evaluations of the entrepreneurial competencies?

- 3.

- How are the entrepreneurial activities of the supervisors visible in the organisation?

- 3.1.

- How do the employees evaluate the entrepreneurial competencies of their supervisors?

- 3.2.

- How do the employees’ evaluations of the supervisors’ entrepreneurial competencies accord with the supervisors’ self-evaluations of their entrepreneurial competencies?

3.2. Assessment Tools and the Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. How Are the Entrepreneurial Competencies Assessed in A (Higher Education) Organisation?

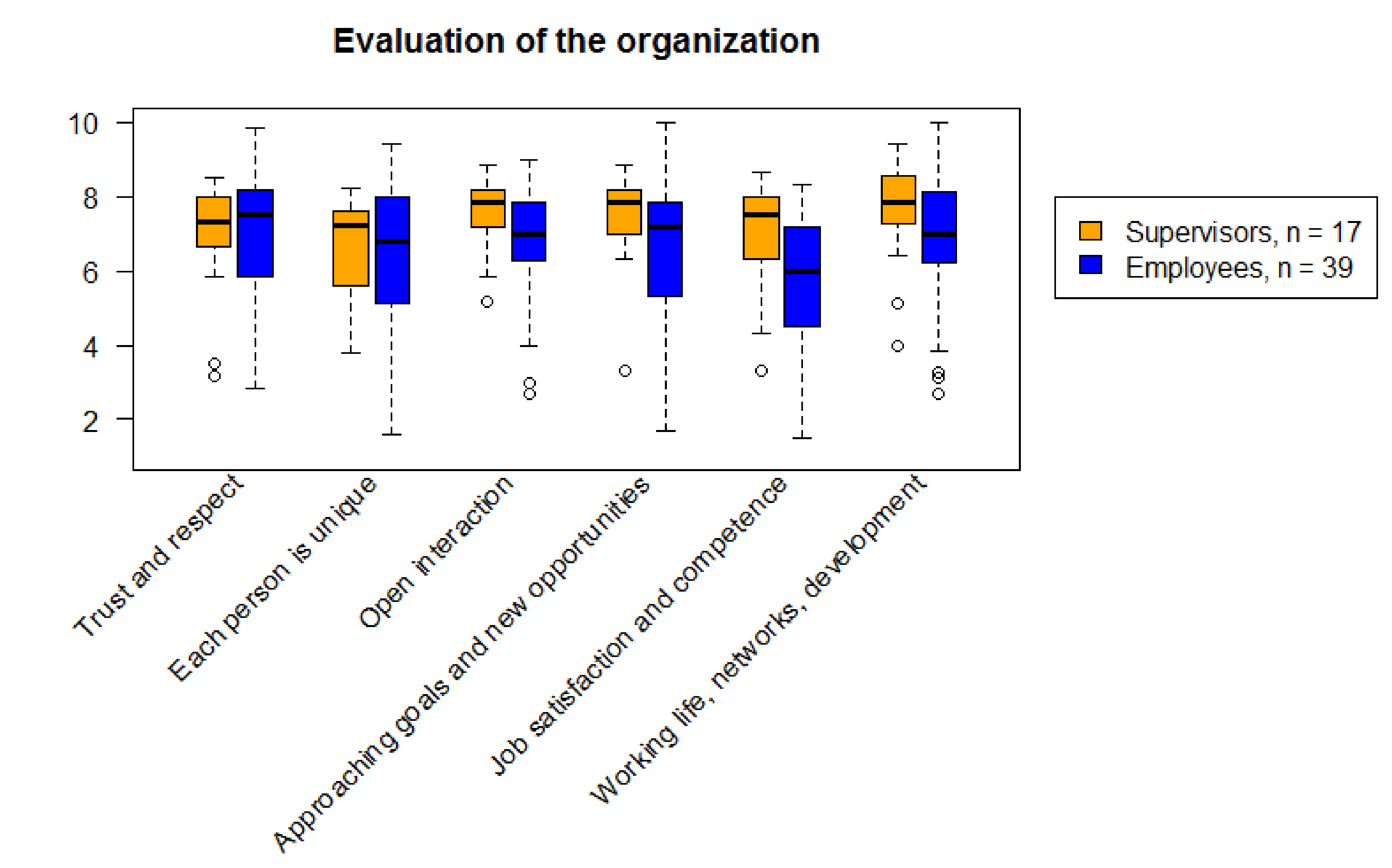

4.1.1. How Do the Employees Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

4.1.2. How Do the Supervisors Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

4.1.3. Are There Any Differences between the Employees’ and the Supervisors’ Evaluations of the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Organisation?

4.2. How Do the Personnel Evaluate Their Own Entrepreneurial Competencies?

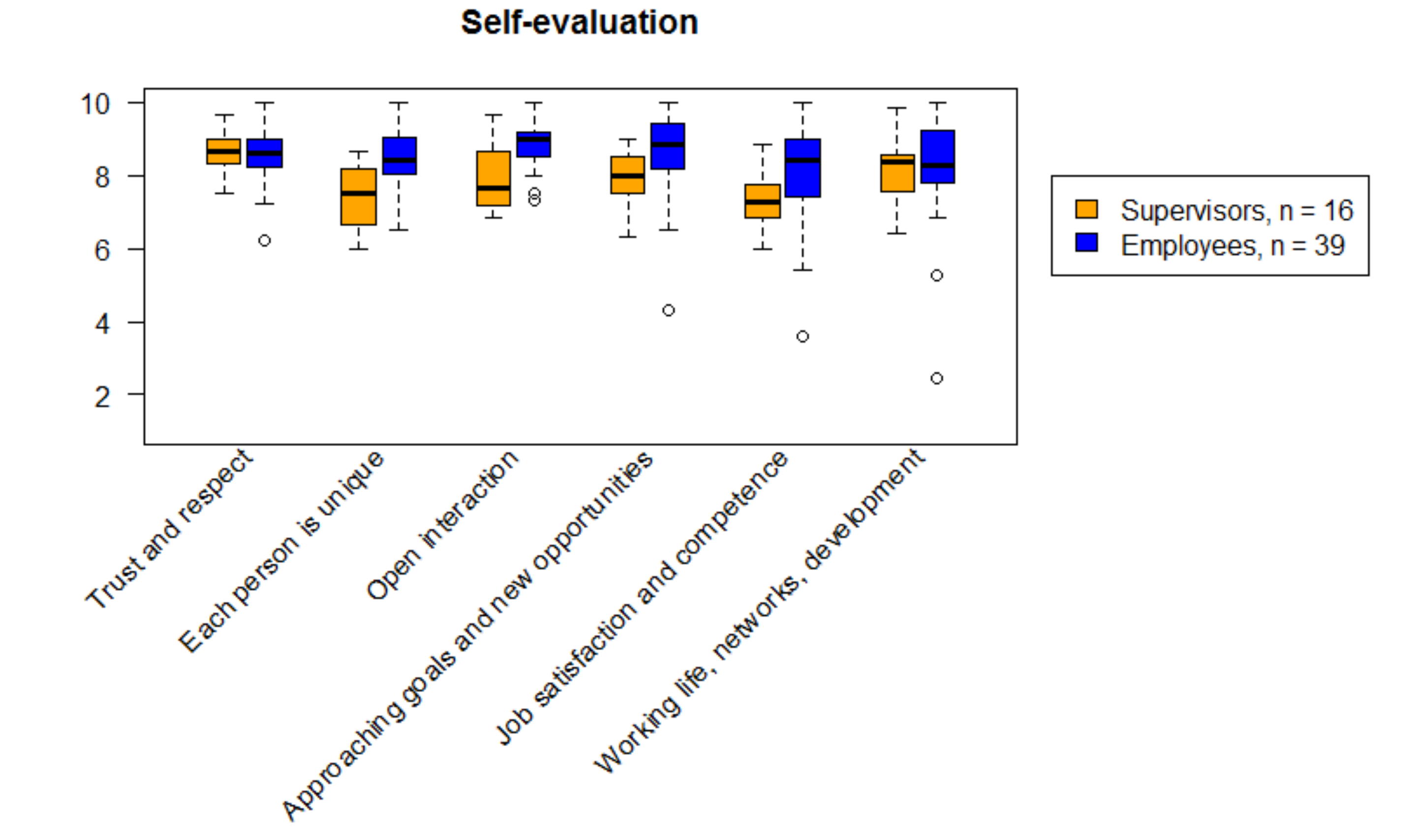

4.2.1. How Do the Employees Self-Evaluate Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

4.2.2. How Do the Supervisors Self-Evaluate Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

4.2.3. Are There Any Differences between the Employees’ and the Supervisors’ Self-Evaluations of the Entrepreneurial Competencies?

4.3. How Are the Entrepreneurial Activities of the Supervisors Visible in the Organisation?

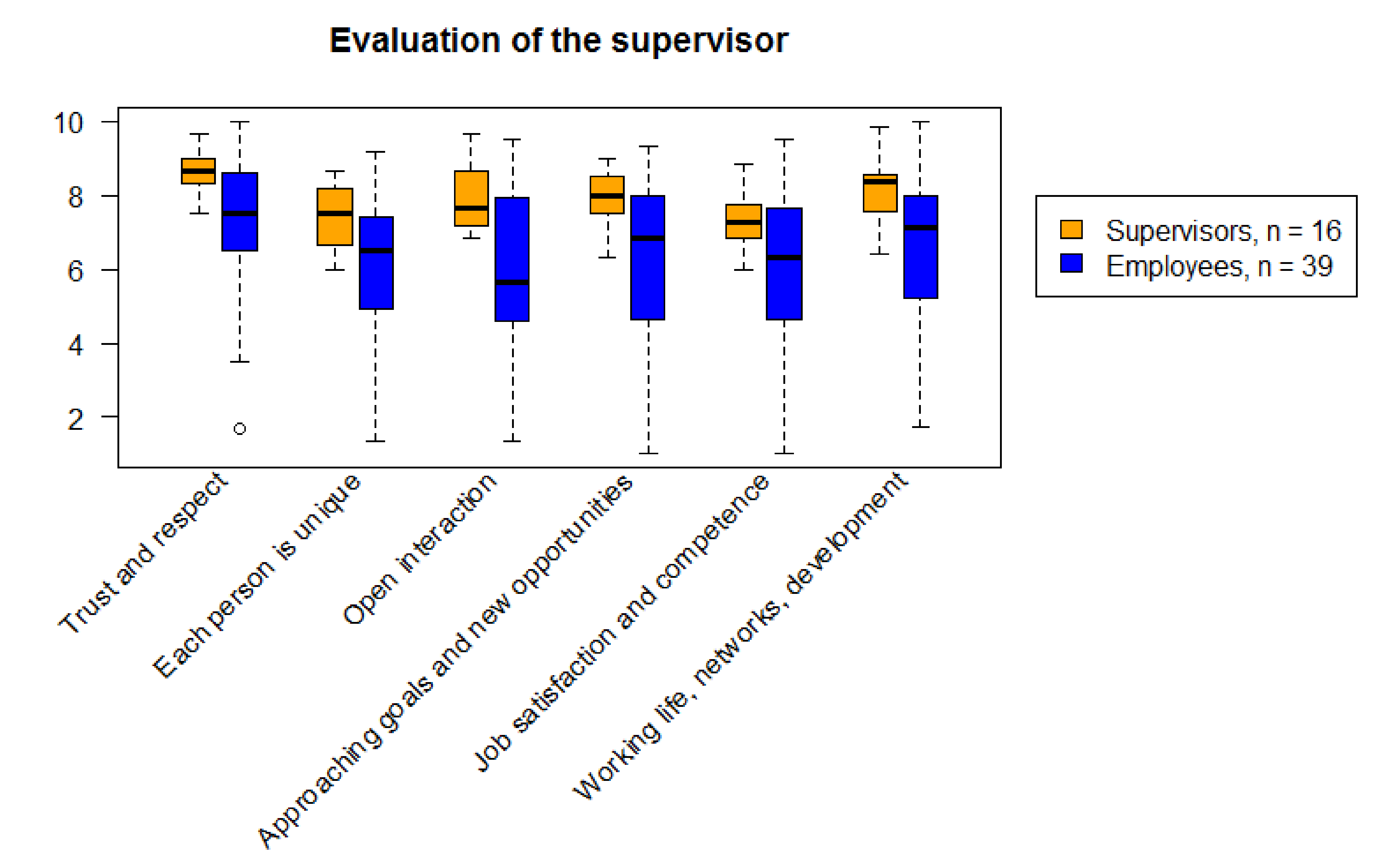

4.3.1. How Do the Employees Evaluate the Entrepreneurial Competencies of Their Supervisors?

4.3.2. How Do the Employees’ Evaluations of the Supervisors’ Entrepreneurial Competencies Accord with the Supervisors’ Self-Evaluations of Their Entrepreneurial Competencies?

4.4. Consistency of the Assessment Tools

5. Discussion and Conclusion

6. Data Availability Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lackeus, M.; Lundqvist, M.; Middleton, K.W.; Inden, J. The Entrepreneurial Employee in Public and Private Sector. What, Why, How; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2020 Global Report, Global Entrepreneurship Research Association: London, UK, 2020.

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Resolving the Knowledge Paradox: Knowledge-Spillover Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Belitski, M.; Audretsch, D. From Latent to Emergent Entrepreneurship: the Knowledfe Spilloever Construction Circle. J. Technol. Transfer 2020, 45, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, G.N.; Jansen, E. The Founder’s Self-Assessed Competence and Venture Performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1992, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfring, T. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Venturing, ISEN International Studies in Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, C.; Grard, F.-M.; Roegiers, R. Quel Avenir pour les Compétences? De Boeck: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, C.; Hirth, M. A History of Change in the Third Mission of Higher Education: The Evolution of One-way Service to Interactive Engagement. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2005, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zomer, A.; Benneworth, P.; Boer, H.F. The Rise of the University’s Third Mission. In Reform of Higher Education in Europe; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vorley, T.; Nelles, J. Building Entrepreneurial Architectures: A Conceptual Interpretation of the Third Mission. Policy Futur. Educ. 2009, 7, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, B.; Maharajh, R.; Schmoch, U. New Activities of Universities in Transfer and Extension: Multiple Requirements and Manifold Solutions. Sci. Public Policy 2009, 36, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Ranga, M.; Benner, M.; Guaranys, L.; Maculan, A.-M.; Kneller, R. Pathways to the Entrepreneurial University: Towards a Global Convergence. Sci. Public Policy 2008, 35, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S.; Guerrero, M.; Noguera, M.; Torrent-Sellens, J. Institutional Determinants of Student Employer Entrepreneurs at Catalan Universities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, B.; Hannon, P. Towards Entpreneurial University? Int. J. Entrep. Educ. 2006, 4, 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Finley, I. Living in an ‘Entrepreneurial’ University. Res. Post-Compuls. Educ. 2004, 9, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N. Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Growth: What do We Know and What so We Still Need to Know? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, G.; Stensaker, B. Bringing Organisations and Systems Back Together: Extending Clark’s Entrepreneurial University. High. Educ. Q. 2017, 71, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Hsu, D.; Powell, B.C. Self-efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intentions, and Gender: Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Longitudinally. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F.; Kickul, J.; Marlino, D. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2007, 31, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, R.; Rodrigues, V.; Stewart, D.; Xiao, A.; Snyder, J. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Behaviour among K-12 Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 72, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borba, M. A K-8 Self-Esteem, Curriculum for Improving Student Achievement, Behavior and School Climate; Jalmar Press: Torrance, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Borba, M. Staff Esteem Builders: The Administrator’s Bible for Enhancing Self-Esteem; Jalmar Press: Torrance, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Seikkula-Leino, J. (submitted): Developing Theory and Practice for Entrepreneurial Learning—Focus on Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Adolescents. In Guide for Constructing Self-Efficacy Scales; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewoord Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credits, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, I.M. Competition and Entrepreneurship; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskovaara, E.; Rytkölä, T.; Seikkula-Leino, J.; Pihkala, T. Building a Measurement Tool for Entrepreneurship Education: A Participatory Development Approach. In Entrepreneurship Research in Europe Series; Edwaerd Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maassen, P.; Spaapen, J.; Kallioinen, O.; Keränen, P.; Penttinen, M.; Wiedenhofer, R.; Kajaste, M. Evaluation of Research, Development and Innovation Activities of Finnish Universities of Applied Sciences; The Finnish Higher Education Evaluation Council: Helsinki, Finland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen, J. Innovation Pedagogy for Universities of Applied Sciences. Creative Educ. 2011, 2, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ilonen, S. Entrepreneurial Learning in Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education; Painosalama: Turku, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seikkula-Leino, J.; Satuvuori, T.; Ruskovaara, E.; Hannula, H. How do Finnish Teacher Educators Implement Entrepreneurship Education? Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikkula-Leino, J.; Ruskovaara, E.; Hannula, H.; Saarivirta, T. Facing the Changing Demands of Europe: Integrating Entrepreneurship Education in Finnish Teacher Training Curricula. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 11, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveci, I.; Seikkula-Leino, J. A Review of Entrepreneurship Education in Teacher Education. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2018, 15, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landström, H.; Harirchi, G.; Astrom, F. Entrepreneurship: Exploring the knowledge base. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Competence Area | Description |

|---|---|

| Trust and respect within the working community | There is trust between the employees and the management, and in the organisation as a whole. There is trust enough to allow mistakes that may lead to new solutions or ideas. |

| Each person is unique | The personnel have an understanding of individual respect, and the personnel are given the space and opportunity to act individually. This also promotes new innovative ways to work in the organisation. |

| Open interaction | A cooperative approach is encouraged at work. The personnel are proud of the team spirit in the workplace. The staff shares ideas. Furthermore, the organisation does not cooperate only internally. Interaction expands to communities outside of the organisation. |

| Approaching goals and new opportunities | The achievement of personal and group goals is supported in the workplace. The personnel are encouraged to seek out new opportunities and ways of doing things to achieve goals. The community participates in decision making. Changes in a working community bring improvements to the work. |

| Job satisfaction and competence | The personnel’s skills are recognized, and the personnel have an opportunity to leverage their strengths in the workplace. There is a feeling that the staff is able to significantly influence one another’s results. The staff evaluates whether objectives have led to results. |

| Working life, networks, development | The workplace supports the development of understanding of different fields and professions, and networking and partnerships with working life and the society around that. A workplace encourages the development/further development of ideas, solutions, or services for customers or other target groups. There is continuous development of competences. Moreover, understanding of entrepreneurship and/or entrepreneurial business is shared within the organisation. |

| Competence Area, Examples | Evaluation of the Organisation (The 1st Assessment Tool) | |

| Trust and respect within the working community | 1. The staff share the same opinion about the common rules. | |

| 2. There is open communication between the employees and the management, and this enables, for example, the proposal of ‘crazy’ ideas. | ||

| 3. There is trust between the employees and the management. | ||

| 4. Employees can count on the promises made by management. | ||

| 5. The rules governing employees are clear. | ||

| 6. We see that mistakes that are made lead to new solutions or ideas. | ||

| Open interaction | 1. It is clear that the personnel are proud of the team spirit in the workplace. | |

| 2. Cooperation is encouraged at work. | ||

| 3. The atmosphere in the workplace means that people keep ideas to themselves.* | ||

| 4. Employees want to work for the benefit of the whole organisation and not only to complete their own tasks. | ||

| 5. The employees have a feeling of unity. | ||

| 6. We actively develop network cooperation with parties outside our working community. | ||

| *Question number 3 was reversed. This was taken into account in our analysis by reversing the answers for this question. | ||

| Competence Area, Examples | Self-Evaluation of Supervisors (The 2nd Assessment Tool) | Self-Evaluation of Employees (The 3rd Assessment Tool) |

| Each person is unique | As a member of the management team… 1. I make an effort to get to know the personal lives of the employees. 2. I send personal messages (e.g., congratulations, condolences, thanks). 3. I regularly consider the uniqueness of each employee; 4. I take into account the efforts of employees. 5. I provide opportunities for employees to get to know each other’s interests. 6. I allow space for employees to take risks when doing new things. | 1. I will take note if my colleague or other member of the work community has succeeded in something. |

| 2. I don’t mind if I act differently to other employees. | ||

| 3. I like to take into account the personal lives of others (birthday, hobbies, children, spouse, etc.). | ||

| 4. I show my appreciation for others. | ||

| 5. I am not afraid of failure, but I boldly try new things. | ||

| 6. I encourage other employees to do new things. | ||

| Approaching goals and new opportunities | As a member of management team… 1. I strive to map employees’ thoughts and ideas on development regularly. 2. I help staff develop a shared vision of what is most important in our workplace for the client or other target group. 3. I make sure that everyone is aware of our mission content. 4. I offer opportunities for shared responsibility. 5. I provide detailed feedback to help each employee achieve their goals. 6. I guide employees towards seeing the positive aspects of change. | 1. I strive to find new opportunities in my work. |

| 2. There are clear goals in my work. | ||

| 3. I strive to reach my goals. | ||

| 4. I try to influence decision-making. | ||

| 5. I understand what the goals of our organisation are. | ||

| 6. I am excited about new challenges in my work. | ||

| Competence Area, Examples | Evaluation of the Supervisors by Employees (The 4th Assessment Tool) | |

| Job satisfaction and competence | As an employee I think that the management… 1. Offers the support I need so I can fulfil the expectations set for me. 2. Enables me to demonstrate my competence. 3. Directs my improvement at work through various methods (e.g., through observation, discussion, leveraging customer feedback, etc.). 4. Clearly states what is good in my work and what could be improved. 5. Helps me to identify the significance of my activities regarding the personal activities of others (target groups/customers, other employees, etc.). 6. Evaluates how I have achieved results. | |

| Working life, networks, development | As an employee I think that the management… 1. Supports the development of my understanding of the various sectors and areas of working life. 2. Directs me towards networking in order to support the development of my work. (Networks include companies, educational institutions, organisations, social actors, etc.). 3. Encourages me to develop/further develop ideas, solutions, or services for customers. (A customer may also be a person or entity who does not pay for a service.) 4. Supports me in developing new solutions that improve my own operations. 5. Supports the continuous development of my own skills. 6. Contributes to strengthening my understanding of entrepreneurship and/or entrepreneurship business. 7. Encourages the search for partnerships from different sectors of society. | |

| Evaluation of the Organisation, Supervisors | Evaluation of the Organisation, Employees | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 6.98 | 6.9 | 0.9502 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 6.58 | 6.43 | 0.768 |

| 3. Open interaction | 7.52 | 6.82 | 0.1025 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 7.24 | 6.46 | 0.1006 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 6.99 | 5.73 | 0.008955 ** |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 7.6 | 6.86 | 0.127 |

| Self-Evaluation, Supervisors, | Self-Evaluation, Employees, | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 8.63 | 8.52 | 0.9929 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 7.48 | 8.41 | 0.000167 *** |

| 3. Open interaction | 7.95 | 8.83 | 0.0005413 *** |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 7.9 | 8.62 | 0.002278 ** |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 7.28 | 7.98 | 0.009078 ** |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 8.11 | 8.26 | 0.504 |

| Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 7.14 | 7.5 | 1.99 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 6.04 | 6.5 | 2.06 |

| 3. Open interaction | 6.11 | 5.67 | 2.07 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 6.15 | 6.83 | 2.25 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 5.97 | 6.33 | 2.32 |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 6.6 | 7.14 | 2.06 |

| Supervisors’ Self-Evaluation | Evaluation of the Supervisors | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 8.63 | 7.14 | 0.000111 *** |

| 2. Each person is unique | 7.48 | 6.04 | 0.000559 *** |

| 3. Open interaction | 7.95 | 6.11 | 2.63 × 10−5 *** |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 7.9 | 6.15 | 6.77 × 10−5 *** |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 7.28 | 5.97 | 0.002704 ** |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 8.11 | 6.6 | 0.000439 *** |

| Total | 7.89 | 6.34 | 2.79 × 10−5 *** |

| Evaluation of the Organisation | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 0.91 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 0.87 |

| 3. Open interaction | 0.83 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 0.91 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 0.88 |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 0.91 |

| Supervisors Self-Evaluation | |

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 0.68 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 0.61 |

| 3. Open interaction | 0.7 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 0.64 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 0.6 |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 0.79 |

| Employees Self-Evaluation | |

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 0.47 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 0.69 |

| 3. Open interaction | 0.52 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 0.81 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 0.77 |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 0.88 |

| Employees Evaluating Supervisors | |

| 1. Trust and respect within the working community | 0.92 |

| 2. Each person is unique | 0.89 |

| 3. Open interaction | 0.89 |

| 4. Approaching goals and new opportunities | 0.95 |

| 5. Job satisfaction and competence | 0.95 |

| 6. Working life, networks, development | 0.95 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seikkula-Leino, J.; Salomaa, M. Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187323

Seikkula-Leino J, Salomaa M. Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187323

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeikkula-Leino, Jaana, and Maria Salomaa. 2020. "Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187323

APA StyleSeikkula-Leino, J., & Salomaa, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability, 12(18), 7323. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187323