1. Introduction

Sustainability research is a widely discussed topic, with the focus on

what should be sustained (environmental issues),

which areas should be developed (the economy and society), and

how it can be maintained (sustainable strategies) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Thus, the concept of sustainability is about conserving, development (economic and non-economic), and maintaining the environment, economy, society, and individuals. The particular role of entrepreneurship in the context of the sustainability concept has been specified [

2,

5,

6,

7]. However, there is still room to keep exploring how the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can enhance economic, social, and sustainable development from an institutional perspective [

8]. Moreover, there is an important current question to be addressed regarding, not only the growth, but also the sustaining of the number of SMEs [

3].

Dynamic changes in the market situation and innovation development complicate the rivalry among different type of firms [

9]. Competition in the dynamic market is specifically harmful to SMEs because they are limited in their tangible resources [

10]. Depending on their resources and competencies, firms develop the strength to gain competitive advantage and enhance their performance, but their lack of resources questions the sustainability of SMEs. Thus, to survive in the market against larger rivals, SMEs should focus more on intangible resources, competences, and dynamic capabilities [

11]. Dynamic capabilities, in comparison with the ordinary ones, underline the need for information acquisition, utilization, and constant transformation to address the environmental threats of an uncertain market [

9]. In this situation, less formalized SMEs are capable of responding to environmental changes in a more agile way [

12].

The implementation of integrated marketing communications (IMC) within an organization can be considered a dynamic capability [

13,

14]. However, the majority of recent studies focus on an analysis of IMC implementation for larger companies, which limits the decision-making process for SMEs [

12]. Recent empirical studies from both a company and customer point of view confirm the positive effect of IMC on organizational performance [

13,

14]. As one of the IMC components, cross-functional coordination facilitates the response to market changes, and message integration positively impacts on customer performance [

14]. Under this condition, less formalized SMEs are capable of responding to environmental changes faster than larger competitors and gain by this extra advantage [

12,

15]. However, the cost of transforming the capabilities may be non-beneficial for young SMEs that need to focus on the short-term to address the liabilities of newness and smallness [

16].

Additionally, as successful IMC implementation requires up-to-date information, a company’s strategic orientation can enhance integration effectiveness [

13,

14]. The lack of analysis on entrepreneurial orientation’s (EO) influence on IMC in SMEs is another limitation that requires further research. But EO effectiveness varies in large companies and SMEs due to organizational and structural issues [

17]. The dynamic capabilities theory underlines the strong relation between managerial behavior and strategic changes in the organization [

18]. The use of EO for successful decision-making in SMEs is related to intrapreneurship (‘in-company entrepreneurship’) [

19]. As a valuable strategic asset of SMEs, EO represents the identification and exploitation of the market [

11,

20,

21]. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in SMEs, EO has a positive impact on the acquisition and utilization of market information and marketing capability, further enhancing organizational performance [

22,

23]. To gain market advantage, SMEs rely on social capital and networking, as well as the endorsement of talent enrichment and individual development [

11,

21]. However, research advises that smaller SMEs, especially in the initial period of their existence, may be less likely to have the experienced managerial talent to build and deploy dynamic capabilities [

16].

The gender issue is a critical concept in sustainability and entrepreneurship research [

24,

25]. Not taking into consideration a possible gender moderating effect may be a significant limitation, given that the owner-manager traits are strongly related to the behavioral characteristics of the SMEs [

25,

26]. Various proposals exist on the gender gaps in entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship in the working environment [

25,

27,

28,

29]. For example, affected by social-cultural obstacles, women entrepreneurs/intrapreneurs may avoid taking risky decisions and evaluate their ‘perceived capabilities’ lower than males [

24,

29]. Another study suggests that female managers evaluate higher firm-level EO but lower performance outcomes [

28]. But, according to the research on individual EO, males are more proactive, risk-taking, and autonomic than females [

25].

Also, the variations in the results of gender effect analysis in the inter-country context underline the need for further examination [

25,

30]. For example, the comparison between the USA and Korea demonstrates that the context affects more the individual EO level in the case of women (no differences in the case of male respondents) [

25]. From the other side, [

30] suggest that females may be more proactive in marketing related management in developed markets compared to developing ones. Institutional theory supports the idea that a company’s behavior may change depending on the context [

31,

32,

33]. The sociological/organizational branch of the theory indicates that the institutional context shapes individual entrepreneurial behaviors [

33] and the undertaking of decisions within the firm [

32,

34]. The economic/political branch of institutional theory emphasizes the role of external formal institutions in management processes [

31,

34]. The institutional networks and institution-based resources, such as access to information, play a vital role for SMEs’ decision-making processes [

35].

Following the above mentioned, this study covers such research gaps as the lack of analysis on IMC implementation in SMEs, the importance of the gender issue in the entrepreneurship research, and the need to clarify the existing variations in the gender gap in the inter-country contest. Thus, the main objective of this article is to study the role of EO as an antecedent of IMC implementation in SMEs with the focus on gender and inter-country multi-group analysis. The following research issues are underlined: (1) the impact of EO on IMC implementation in SMEs, (2) the influence of IMC on performance in SMEs, (3) the gender moderating effect in the theoretical model, and (4) the country moderating effect in the theoretical model.

Based on the research gaps, the data from 315 SME managers’ surveys (in Spain and Belarus) was analyzed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). Multi-group analysis technique was applied for testing gender and country moderating effects. Some similarities and valuable differences underline the choice of the countries selected for analysis. Following World Bank data and the Entrepreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global (GEM) Report, Spain represents a developed market with good data availability, developed financial markets, technology, and research and development (R&D) investment compared to Belarus, which is an emerging economy [

7,

36,

37]. Both countries demonstrate recent economic growth [

36]. They are in the same region/group in the GEM report and share some similar characteristics in entrepreneurship activities (such as physical infrastructure and entrepreneurial education at the school stage) [

7]. However, the weighted average state of the set of national entrepreneurship framework conditions in Belarus (4.24) is lower than in Spain (5.24), with the notable differences in entrepreneurial finance, government policies, R&D transfer, and commercial and legal infrastructure [

7]. Furthermore, spending on marketing (including spending on IMC tools) as a share of GDP is much higher in Spain (0.49%) than in Belarus (0.17%). However, the internal market dynamic and average increase in annual marketing expenditure is higher in Belarus (15%) than in Spain (5.8%) [

38,

39], confirming the developmental dynamics of the Belarusian market.

This study contributes to sustainability, entrepreneurship, and marketing research by connecting the company’s strategic orientation with marketing communications in SMEs. The focus of the analysis on the SME sample closes the gap on the lack of IMC implementation analysis among SMEs. Moreover, it focusses on the importance of gender issues in sustainability and entrepreneurship research. Finally, the institutional context and inter-country analysis aim to generalize the research results in an international setting.

From a managerial perspective, the research sheds light on the issues related to practices of the EO role in dynamic capabilities implementation and their contribution to the sustainable competitive advantage of SMEs. This is a valuable issue considering the vital role of SMEs in the sustainable development of the economy and society. Gender issue investigation adds to understanding the role of the manager in SMEs and the effect of intrapreneurs’ behavior on a company’s performance. The inter-country analysis clarifies the environmental and institutional context in different regions, economies, and markets, along with its effect on managerial behaviors and organizational outcomes.

Section 2 starts with a literature review and outlines the hypotheses to be tested. Then,

Section 3 explains the context, data collection, and analysis. Next,

Section 4, based on an analysis of the data, presents the research reports, and

Section 5 discusses the results.

Section 6 comments on the theoretical contributions and practical implementations. Finally,

Section 7 lists some limitations and provides suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The topic of sustainability is widely discussed in the literature [

2,

3]. Recent research defines sustainability in the following ways:

what should be sustained (emphasizing the environmental issues, natural resources, and community);

which areas should be developed (with the focus on the economy, individuals, and society); and

how it can be maintained (with the emphasis on sustainable strategies) [

1,

2,

4]. In summary, the concept of sustainability can be defined as the protection, development (economic and non-economic), and maintenance of nature, the economy, society, and individuals.

In the current state of the theoretical and practical context, the growth and sustaining of SMEs is considered to be directly related to sustainable development [

3,

8]. Scientific research states that SMEs play an essential role in new job creation, the counteracting of inflation, increased productivity, innovation, networking, and communities [

2,

5]. SMEs also provide individuals and society with non-economic gains [

6,

7]. Previous studies from entrepreneurship literature and official publications (such as the GEM) affirm the particular importance of small businesses in sustainable development [

7].

However, as SMEs are limited in their number of tangible resources, intense competition threatens their survival in the market against larger rivals [

10,

15,

16,

40]. Changes in the dynamic market and innovation development create uncertainty and complicate the rivalry among different types of firms [

41]. It motivates companies to be more proactive in searching for a competitive advantage [

9,

18]. More usually, to advance in the market, firms rely, not just on resources that are important for performance outcomes, but also on searching for customer-linking capabilities [

18,

41,

42]. Reasonably, instead of focusing on tangible resources, SMEs could concentrate more on intangible resources and dynamic capabilities [

11,

16].

2.1. IMC as SMEs Capability

The dynamic capabilities theory proposes the strategic actions that the company should undertake if aiming to gain and sustain competitive advantage [

18,

41]. The theory claims that, complementary to the need for information acquisition and utilization as a part of ordinary capabilities, the constant capabilities transformation to address the environmental threats of an uncertain market is needed [

9,

16]. Previous research confirmed the significant role of marketing capabilities, including marketing communications, in empowering a company’s competitive strategies [

42,

43,

44]. Specifically, the power of IMC as a market capability drives the achievement of a superior performance [

13,

14,

42]. In particular, a company accumulates market intelligence (including competitor actions and changes in customer preferences) and senses environmental changes (such as the appearance of new technologies). Using the data collected, managers take decisions about capturing internal resources and competences and transforming them into integrated communicational actions that address the changing, uncertain environment [

13,

18,

41]. The possibility of using IMC as one of a company’s dynamic capabilities additionally supports the suggestion of its favorable implementation in SMEs [

11,

16,

17].

However, smaller SMEs, especially in the initial period of their existence, may be less likely to have the experience managerial talent to build and deploy dynamic capabilities. Furthermore, the cost of transforming the capabilities does not benefit young SMEs that need to focus on the short-term in order to address the liabilities of newness and smallness [

16]. This may inhibit the effectiveness of IMC implementation as a dynamic capability in SMEs. From the other side, it is suggested in the literature that, for the successful implementation of IMC, the company must apply cross-functional coordination and have a certain level of flexibility [

13,

42,

45]. Various studies underline that SMEs being more flexible and simpler in their organizational structure are better at cross-functional coordination and sharing the information within the organization [

17,

19,

46]. Simpler coordination together with a less formalized organizational structure may facilitate SMEs’ faster response to the changes in dynamic market environments [

14,

15,

17]. Moreover, studies suggest that SMEs may also be successful in integration due to the simplicity of their communication activities [

46]. Specifically, SMEs are more likely to practice IMC because they target fewer market segments and use fewer communication messages. Furthermore, other studies advise that better informed managers and fewer numbers of communications facilitate better message and channel integration, which positively impacts on a company’s performance [

14,

19]. Thus, SMEs could gain an edge over their larger rivals in IMC effectiveness [

11,

17]. Following on this, we suggest that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). IMC has a positive impact on organizational performance in SMEs.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Orientation as an Antecedent of Successful IMC Implementation in SMEs

Entrepreneurial literature defines EO as a company’s strategic asset representing the intensity with which firms establish the identification and exploitation of untapped opportunities as a management principle of the firm [

15,

20,

47]. Studies focusing on the analysis of SMEs additionally specify that, due to organizational and structural differences compared to larger companies, there is a deeper connection between EO due to the existence of intrapreneurship [

15,

19]. The concept of intrapreneurship (which derives from the phrase ‘in-company entrepreneurship’) describes with which internal and external characteristics a firm’s ‘entrepreneurial’ orientation is associated, and under what conditions this orientation results in a superior performance [

19,

27].

Specifically, the scientific literature mentions that the development of intrapreneurs in SMEs is important, as the decisions on product innovation, risk-taking, and proactive behavior are always taken by managers [

18,

28,

48]. Additionally, the dynamic capabilities theory underlines the strong relation between managerial behavior and strategic changes in the organization [

18], and research demonstrates that employees with a higher level of individual EO tend to be more proactive, explore new opportunities, and implement them [

49]. Therefore, in order to gain market advantage, SMEs, develop social capital, endorse talent enrichment and individual development, and advance networking [

11,

15,

21,

42].

Previous studies focused on SMEs demonstrated that EO has a positive impact on the acquisition and utilization of market information, on marketing capability [

22], and the further enhancing of organizational performance [

23]. Firms pursuing innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking are more likely to make strategic decisions and upgrade core capabilities in a dynamic environment [

22]. Thus, the company’s strategic orientation could enhance integration effectiveness as a successful IMC implementation [

50]. Therefore, we state that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). EO has a positive impact on IMC in SMEs.

2.3. Gender Issues in Managerial Decision-Making

Entrepreneurship research emphasizes the gender impacts on decision-making [

25,

26]. The literature demonstrates various proposals regarding the gender gap in entrepreneurship/ intrapreneurship in the working environment [

25,

28,

29].

Specifically, compared to men, research has demonstrated that female entrepreneurs/intrapreneurs have higher pressures from social-cultural obstacles such as ‘the fear of failure’ and ‘perceived capabilities’ [

24]. Among others, several informal factors (the recognition of an entrepreneurial career and female networks) and formal factors (education, family context, and differential of income level) may affect the decisions of female owner-managers [

51]. In this case, even knowing that IMC may have a positive effect on the company’s performance, female managers may avoid implementation of risky changes related to process innovation [

29]. Furthermore, immaterial of their true skills, women may undervalue their ability to implement the strategy successfully or estimate in a less positive way the possible results/outcomes of IMC implementation [

24]. The empirical analysis of individual EO suggested that, in comparison with men, women have lower rates of both entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial activities [

25,

28]. The decisions of females may involve lower degrees of risk-taking, innovativeness, aggressiveness, and autonomy [

25,

29,

30]. It may neglect the positive effect of EO on IMC.

However, the research suggests that female managers may evaluate higher the firm-level of EO but lower the level of performance outcomes [

28]. There is also a suggestion that, under specific environmental conditions of developing markets, female managers may be more effective in the implementation of marketing-related strategies [

30,

52]. Nevertheless, even presenting inconsistent results, all the previous researchers underline the influence of the manager’s gender and the possibility for SMEs to sustain themselves in the market [

25,

29,

30,

51,

52]. Consequently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Gender moderates the EO-IMC relationship in SMEs.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Gender moderates the relationship between IMC and organizational performance.

2.4. Inter-Country Comparison

Institutional theory states that a company’s behavior varies depending on the context [

31,

32]. The economic/political branch of institutional theory emphasizes the role of external formal institutions and institution-based resources [

31,

34]. There is a lower level of market activity and rivalry in emerging markets compared to developed ones [

13]. Therefore, there is less information available, lower competition, and less networking opportunities in emerging markets. The deficit of institution-based resources—such as access to information—may impact negatively on managers’ decision-making [

13,

35]. Additionally, the lack of institutional networks may have a negative influence on business practices in SMEs [

29].

Also, the sociological/organizational branch of institutional theory implies that the context shapes individual entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial behavior, and the undertaking of decisions within the firm [

32,

33,

34]. Specifically, significant differences have been demonstrated in IMC implementation effectiveness between developed and emerging markets [

13]. The higher level of environmental turbulence in developed markets enhances motivation to improve the relationship between a strategic orientation and performance in SMEs [

40]. Furthermore, the pressure of risk-avoidance is more significant in emerging markets, where managers prefer to avoid decisions that may have uncertain outcomes. Even being aware of the advantage of process innovation (the implementation of IMC practices), decision-makers prefer to invest in production and product innovation [

31,

53].

Additionally, variations in the environmental context may affect personal values and lead to inconsistencies in the strategies adopted by women and men [

25,

30]. In contrast to developed markets, in emerging economies, women owner-managers are more proactive in marketing related management and less successful in strategic, financial, and HRM (Human Resources Management) planning [

30]. Thus, in an emerging market, IMC performance outcomes may be higher in the case of a female rather than a male manager [

25,

30]. Moreover, previous studies suggest that in various markets there may exist differences in the outcomes for females, but not for males. For example, one study [

25] illustrates notable differences in intrapreneurial activity in the comparison of US and Korean students. Male respondents are more risk-taking and competitively aggressive. They engage more often in innovativeness and rely on a higher level of autonomy, depending less on spouses, family, and friends for help [

29]. However, these differences are not significant when comparing only male respondents (when the female group is excluded from the analyses). Thus, we suggest that:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Economy type moderates the EO-IMC relationship in SMEs.

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Economy type moderates the relationship between IMC and organizational performance.

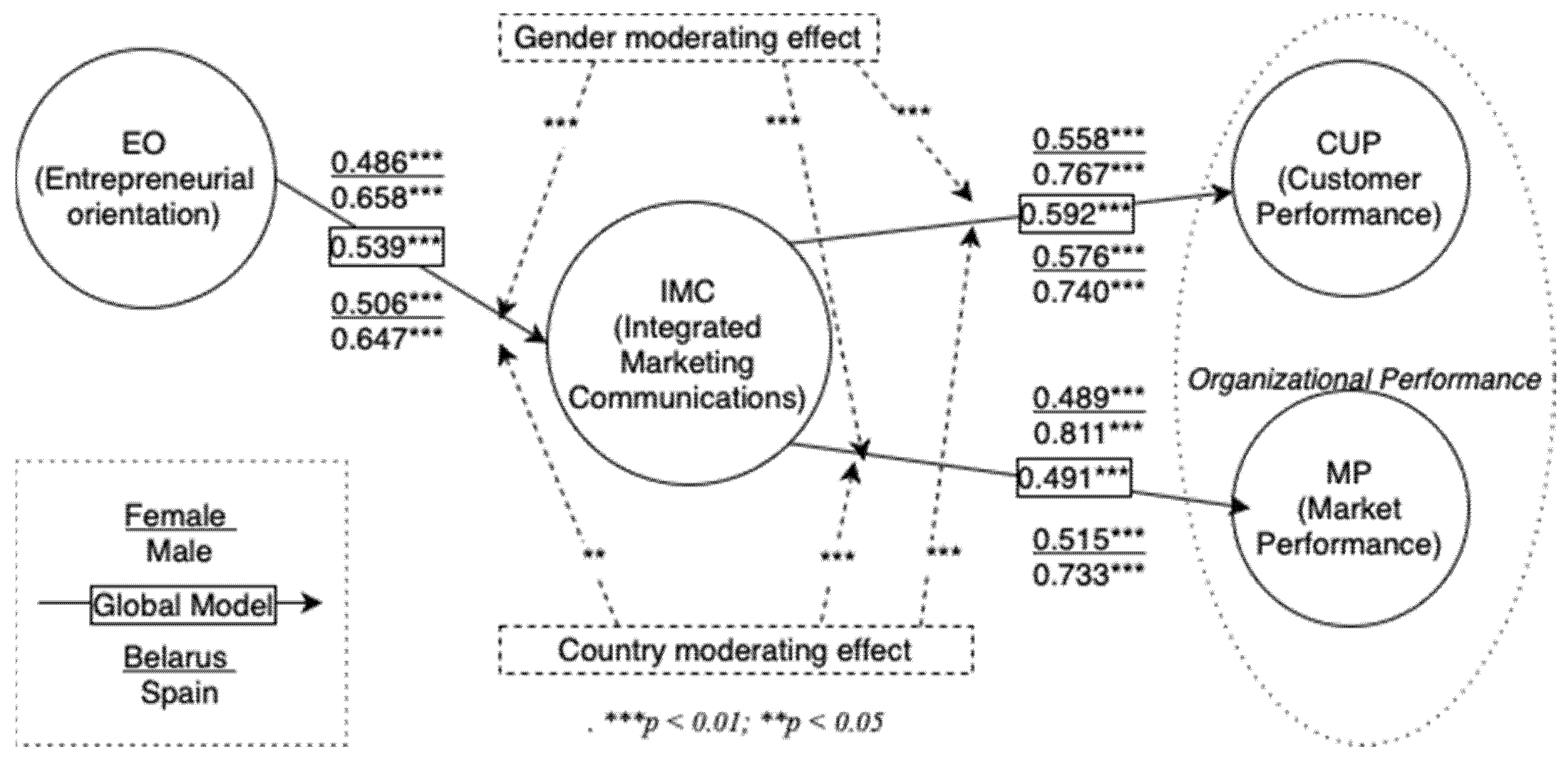

4. Results

The results of testing the theoretical model (

Table 2) demonstrate that EO has a significant positive impact on IMC (H1: 0.539,

p < 0.01). Furthermore, IMC has a significant positive impact on performance: customer (H2: 0.592,

p < 0.01) and market performance (H3: 0.491,

p < 0.01).

The results of gender moderating effect analysis in

Table 3 suggest that, in SMEs where managers are male, compared to ones where they are female, EO has a significantly stronger effect on IMC (H4a

female: 0.486 vs. H4

male: 0.658;

p < 0.01), and IMC has a significantly stronger effect on customer performance (H4b

female: 0.558 vs. H4b

male: 0.767;

p < 0.01) and market performance (H4c

female: 0.489 vs. H4c

male: 0.811;

p < 0.01).

Following the results of country moderating effect in

Table 4, the relationships between EO and IMC in SMEs are significantly stronger in the developed economy when compared with the emerging economy (H5a

Belarus: 0.506 vs. H5a

Spain: 0.647;

p < 0.05); the same is true for the relationships between IMC and customer performance (H5b

Belarus: 0.576 vs. H5b

Spain: 0.740;

p < 0.01) and IMC and market performance (H5c

Belarus: 0.515 vs. H5c

Spain: 0.733;

p < 0.01).

Figure 1 presents the results of the global model analysis and testing gender and country moderating effects.

Deeper results on the gender gap analysis in the inter-country context are presented in

Table 5. The data from the global sample is analyzed separately for Spain and Belarus. The analysis suggests that, in a developed market, similar to the data from the global sample, the EO-IMC-performance relationship is significantly stronger for male respondents than it is for female ones. However, in the case of Belarus (an emerging market) there are no significant differences.

Furthermore, the multi-group analysis for the country moderating effect was done separately for male and female respondents. The results in

Table 6 suggest that, like the global model, the EO-IMC-performance relationship in the case of a male manager is significantly stronger in a developed market (Spain) (

p < 0.01). Conversely, in the case of female managers, the EO-IMC-performance relationship is significantly stronger in the case of developing market (

p < 0.01).

5. Discussion

As has been suggested, the results confirm that EO has a positive effect on IMC implementation in SMEs, and IMC has a further positive impact on organizational performance (customer and market). Thus, hypotheses H1 and H2 are supported. In addition to the previous findings on the positive effect of EO on market capabilities and organizational performance in SMEs [

22,

23], this suggests that IMC can be a source of competitive advantage for SMEs.

However, the research indicates a significant moderating effect of gender on the EO-IMC-performance relationship. Thus, hypotheses H3 and H4 are supported. This result is congruent with previous research that demonstrates the existence of a gender gap in the working environment [

24,

44]. Specifically, the impact of EO on IMC in SMEs is significantly more intense when the manager is a male. These results may additionally support the suggestion about a deeper connection between EO and intrapreneurship in SMEs [

15,

19]. The explanation could be the fact that, in comparison with men, women have lower rates of individual EO and intrapreneurial activities [

25,

28]. The IMC impact on organizational performance (customer and market) is also considerably higher in the case of male managers. These results could be related to the social-cultural pressure and possible underestimating of their capability level perception [

22]. Additionally, the reason could be due to the lower degree of risk-taking, innovativeness, aggressiveness, and autonomy of females [

24,

25,

29,

30]. Furthermore, the conditions of SMEs, where the decision-making and sharing of managerial responsibilities are limited, could be an additional obstacle for female managers [

46].

The economy type moderating effect analysis also confirms the inter-country differences in the EO-IMC-performance relationship in SMEs. Thus, hypotheses H5 and H6 are supported. The effect of EO on IMC is significantly higher in a developed economy compared to an emerging one, and the same is true for the IMC outcomes for organizational performance. This supports previous research demonstrating the lower effectiveness of a strategic orientation on IMC in emerging economies [

13]. This confirms that market turbulence in developed markets motivates SMEs to apply EO practices more [

40]. Moreover, the lack of networking, less available market information, and the rejection of risk-related decisions in an emerging market all reduce IMC implementation effectiveness in SMEs [

13,

29].

Further multi-group analysis of the gender moderating effect separately in each country presents additional insights. Meanwhile, the relationships in the model are stronger for male than for female managers in the developed market; however, there is no significant gender moderating effect in the emerging market. This means that there is a gender gap among managers of SMEs in Spain, but no gender gap in Belarus. A possible reason for the lack of gender differences in the emerging market could be that both male and female behavior tends towards risk-avoidance [

12]. Perhaps due to the limit of resources or market information, even being aware of the implementation of IMC practices, managers in developing markets prefer to invest in production and product innovation [

31,

53].

There is also a contrast in country moderating effect when testing male and female groups of respondents separately. In the case of male managers, as in the global sample results, the relationships in the model are significantly stronger in the developed market compared to the emerging one. Interestingly, the results are the opposite for the analysis of data from the female respondents. When the manager is a female, contrary to the mixed sample, the EO-IMC-performance relationship is considerably more intense in the emerging market. This supports the suggestion that the institutional conditions may affect females and males differently [

25,

54]. It also means that female managers in emerging markets may be more efficient in functional strategies in the area of marketing [

30]. As is similar to the previous studies, these results can probably be explained by the variation in the perception of the values [

45]. The socio-cultural obstacle of the ‘fear of failure’ for females in emerging markets may be lower. This could be explained by the lower level of competition in the labor market and, as a consequence, a diminished fear of losing a job and career opportunities; or it could be due to the longer period of maturity stays and the fact that there is more focus on family rather than on career in emerging countries.

6. Conclusions

This research has valuable theoretical and practical contributions to make to the study of marketing, entrepreneurship, and sustainability topics with a specific focus on SMEs, gender issues, and inter-country context. Specifically, the empirical analysis covers the gap in explaining the possible use of EO as an antecedent of IMC as a source of competitive advantage in SMEs. Additionally, the research focuses on the analysis of the important sustainability and entrepreneurship research gender issues. The results underline the significant differences among male and female managers, which may affect the effectiveness of IMC implementation in SMEs. Additionally, this study helps to generalize the results in the inter-country context. The outcomes of the analysis highlight the significant differences in EO-IMC-performance relationships in developed and developing markets. Finally, this article further covers the effect of the institutional environment on the variations in the gender gap between markets.

These are relevant enrichments as SMEs play a significant role in the sustainable development of economies and societies. They provide, not only economic gains, but also resource social capital, endorse talent advancement, and stimulate individual development [

2,

5,

6,

7,

11]. The sustainability literature underlines the importance of both the growth and sustaining of SMEs [

3,

8]. Additionally, gender is considered to be an important issue in sustainability and entrepreneurship research [

24,

25]. The managers’ profile was considered to play a significant role in SMEs [

25,

26]. Finally, the effectiveness of managerial practices varies in the international context [

13,

14].

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

Specifically, the study covers the gap in understanding IMC effectiveness for SMEs and the role of entrepreneurial orientation in enhancing IMC effectiveness, which contributes to better organizational performance. Our results confirm that IMC can be considered a dynamic capability for SMEs. The study of the gender gap in this research contributes more to understanding the role of intrapreneurs in firms. The results suggest that IMC effectiveness is higher in the case of male managers.

The inter-country perspective and application of institutional theory in this research is an additional contribution towards generalizing the results in the international context. The study states that, in the emerging economy compared to the developed one, the EO impact on IMC implementation is lower. Furthermore, the IMC outcomes for the organizational performance (customer and market) are weaker. The lack of a developed institutional formal context, fewer networking opportunities, and scarcity of institutional resources, such as market information, probably hurts SMEs’ opportunities in gaining a sustainable competitive advantage.

Additional analysis of gender moderating effects separately in Belarus and Spain contribute to a deeper understanding of the gender gap in SMEs in the inter-country context. In the case of the developed market, the gender impact on the EO-IMC-performance relations is significantly weaker when the manager is female. In the emerging market, there is no significant gender gap. Probably in the situation of lack of resources and no available market information neither female nor male managers are able to implement risky decisions related with IMC implementation processes effectively.

The country moderating effects analysis independently in the case of male and female managers and contributes deeper to understanding the institutional context effect on manager behavior. In the case of male managers, EO-IMC-performance relationships are more intense in a developed market. In the case of the female manager, conversely, these relationships are more intense in emerging markets. Thus, female managers are probably more affected by social-cultural obstacles and avoid making risky decisions due to ‘fear of failure’ in developed markets. In emerging markets, women tend to be more efficient than men in applying marketing related strategies. Additionally, the variations in results additionally confirm the importance of multi-group analysis of moderating effects in marketing research.

6.2. Practical Implementation

From the practical perspective, the orientation towards new opportunities in the market, together with the flexibility and formalization of SMEs, facilitates the integration processes. Proactiveness, risk-taking, and innovativeness have a positive effect on the message/channel integration and cross-functional coordination in SMEs. This results in higher customer satisfaction, an increase in repurchase intention, a higher market share, and more opportunities for new customer acquisition. Thus, IMC can be considered to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage for SMEs. The loss of IMC effectiveness may reduce the positive effect on organizational performance and the possibility of SME survival in the market.

The results additionally confirm the importance of the owner-manager profile for the success of SMEs [

42]. Thus, the practices supporting the entrepreneurs/intrapreneurs may help individual development and the survival of SMEs in the market. The extra support, networking possibilities, and sharing of responsibilities, together with specific educational programs on risk-management, can be helpful. They may facilitate accepting more risky choices and, as a result, increase the number of innovative decisions among managers in SMEs.

The inter-country analysis shows extra complications for SMEs looking to gain a competitive advantage in the emerging markets. As a solution, specific plans can be applied to provide small and medium companies with extra information resources and to facilitate networking opportunities.

The lack of a gender gap may mean that the manager’s profile is less important in emerging markets compared to developed ones. In the situation of scarce resources and limited information, both male and female managers need extra support. Additionally, the institutional context of an emerging environment negatively impacts the male managers’ decision-making effectiveness. Thus, similar to the previous suggestion, resource and information support may be helpful for the survival of SMEs in the case of male managers. Conversely, it is interesting that the emerging market environment has a favorable impact on female managers. In developing markets, contradicting the results in developed ones, female respondents show more effectiveness in the implementation of marketing strategies than male managers. Socio-cultural and institutional factors such as the lower dedication of females to a career, more days of the maturity stage, or less competition in the labor market, among others, should also be mentioned.