Abstract

Since 2005 until today, experience has been gained in the preparation, implementation and impacts of the evaluation of the management effectiveness of German national parks. This process began with the development of a quality set containing fields of action, criteria, standards and a questionnaire to assess the state of national park management. This quality set was applied in the first voluntary full evaluation of German national parks, which took place from 2009 to 2012. An assessment of the full evaluation and the following interim evaluation (2015–2018) demonstrated the positive effects of the evaluation for the national parks, but also revealed some weaknesses of the quality set and the evaluation process. For this reason, work has been underway since 2019 to further improve the evaluation method; however, this has not yet been completed. The article provides an overview of the entire process. It concludes with considerations on the transferability of the evaluation method to other countries and gives some recommendations as to the most important aspects to be considered when evaluating the management effectiveness of national parks.

1. Introduction

The worldwide decline of biodiversity led to the adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) [1] at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro. In 2004, the 7th Conference of the Parties to the CBD (COP 7) adopted the “Programme of Work on Protected Areas” [2], which emphasizes the importance of protected areas for achieving the objectives of the Convention and requests that by 2015 management effectiveness evaluations be carried out for at least 60% of the total protected area of each signatory state.

Worldwide, a large number of evaluation systems for protected areas exist [3,4,5]. In Europe, a systematic evaluation of all national parks of a country has only been carried out in a few countries: Germany, Austria [6], Finland and the Netherlands [7]. For the German large-scale protected areas (national parks, biosphere reserves and nature parks) different criteria sets and evaluation systems have been established and compared by Scherfose 2013 [8], whereas Coad et al. 2013 [9] and Gannon et al. 2019 [10] report on global progress in the evaluation of protected areas.

To fulfill the above mentioned requirements of the CBD, EUROPARC Deutschland (hereafter referred to as EUROPARC Germany), the umbrella organization of Germany’s large protected areas, supported by the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN, Bundesamt für Naturschutz), initiated the development of a quality set for German national parks between 2005 and 2008 and conducted a subsequent voluntary evaluation process from 2009 to 2012 [11,12,13,14]. Between 2015 and 2018, an interim evaluation was carried out in order to determine the impact of the full evaluation. The quality set, consisting of fields of action, standards, criteria and a questionnaire, is currently being revised on the basis of experiences gained to date.

The evaluation pursues the following main aims ([11,12], modified and amended):

- Identification of successes and shortcomings of national parks and the respective underlying causes

- Maintenance and improvement of the national parks’ management quality in the long term

- External support for national park administrations, their requirements and needs

- Promotion of professional exchange

- Contribution to the implementation of the “Programme of Work on Protected Areas”.

The first German national park (Bavarian Forest) was established late, in 1970. In 2005, when the evaluation process was started, 14 national parks existed in Germany. In 2014 (Black Forest) and 2015 (Hunsrück-Hochwald), two more national parks were established and the discussion on the foundation of further national parks is still ongoing [15,16]. Figure 1 provides an overview of the parks’ geographic distribution. They include different landscape and ecosystem types: the Wadden Sea and coastal areas, lake areas and river floodplains, high mountain ranges in the alps and different types of forests, e.g., beech forests which are partly designated as UNESCO World Natural Heritage (Figure 2). The 16 national parks cover a total area of 1,047,859 ha, including marine areas; and 205,655 ha excluding marine areas. Their size differs substantially, ranging from 3070 ha (Jasmund) to 441,500 ha (Wadden Sea Schleswig-Holstein). The size of the national parks without marine areas is between 5738 ha (Kellerwald-Edersee) and 32,200 ha (Müritz). All but three of the parks reach the minimum size of 10,000 ha, as suggested by the quality set for German national parks [11,12]. For further information, see https://www.bfn.de/themen/gebietsschutz-grossschutzgebiete/nationalparke.html.

Figure 1.

German national parks (Source: Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN), 2019, according to the basic geodata of the federal states: © GeoBasis-DE/BKG 2018 https://www.bfn.de/en/activities/protected-areas/national-parks.html, accessed 30 June 2020).

Figure 2.

Impressions from German national parks: (a) Jasmund, chalk cliffs at the Isle of Rügen in the Baltic Sea; (b) Saxon Switzerland, sand stone erosion landscape; (c) Hainich, Thuringia, also designated as UNESCO World Natural Heritage site for its beech forests; (d) Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, view to Königssee in the management zone, a popular tourist destination. (Photos: a–c: Nationale Naturlandschaften e.V., K. Sabry, A. May, S. Schubert; d: M. Günther).

German national parks are managed in line with the IUCN’s requirements for protected areas’ management category II [17], although many of them do not yet meet all the requirements of this category. This concerns, in particular, the minimum proportion of 75% of the entire park, which must be dedicated to dynamic natural processes without human interference or land use (“nature dynamics zone”, often also named “core zone” or “nature zone”). Since Germany’s national parks are regarded as “development national parks” [18], they have to achieve this percentage only 30 years after their establishment. Moreover, this figure is not laid down in the German Federal Nature Conservation Act, which requires a nature dynamics zone proportion of at least 50% of the total park area, and the nature conservation laws of the individual federal states. However, the 75% target is explicitly mentioned in some national park acts and/or ordinances and also included in the evaluation quality set [11,12,14].

Since national parks comprise about 0.6% of Germany’s terrestrial area, they also contribute substantially to the implementation of the German National Strategy on Biological Diversity [19], which states that 2% of Germany’s terrestrial area should be designated as “wilderness areas”.

This article aims to provide an overview of the results of, and experiences with, the evaluation process to date and discusses what conclusions other countries could draw from it for similar projects. Insights are provided from the different perspectives of the authors: Volker Scherfose accompanied the entire process since 2005 as project supervisor, on behalf of the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation. Stefan Heiland acted—from a scientific point of view—as spokesperson of the evaluation committee from 2009–2012, as the main author of a “cross-section evaluation” (giving an overview of the evaluation results of all national parks) and an external advisor of the interim evaluation and the current process on further developing the evaluation’s quality set, consisting of criteria, standards and a questionnaire to examine the standards (see Section 2, Projects 2–4). Anja May was the responsible project manager of the interim evaluation and is currently in charge of the further development of the evaluations’ quality set (see Section 2, Projects 3 and 4).

2. Materials and Methods

This article is based upon, and reflects, the results of four consecutive research and development projects on the evaluation of the management quality of German national parks. During the first project, the evaluation criteria and the process were defined, the second project encompassed the evaluation of all national parks, the third an interim evaluation carried out five years after the full evaluation and the fourth, still ongoing project is dedicated to the improvement of the quality set and the evaluation process, building upon the experiences of the second and third projects.

All projects were financed by the German Environmental Ministry, supervised by the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation and carried out under the leadership of EUROPARC Germany e.V. (renamed to Nationale Naturlandschaften e.V. in January 2020). To ensure the widest possible acceptance of the entire process, political support and the greatest practical benefit for the national parks, a variety of actors from different backgrounds participated. First of all, all German national park administrations were intensively involved from the first development of quality standards and criteria, between 2005 and 2008, and the subsequent full and interim evaluation to the current revision of the evaluation criteria and standards. Secondly, representatives of NGOs, universities, consultancies and “LANA” were and are still involved (LANA: “German Inter-State Working Group for Nature Conservation”, a committee founded to allow for cooperation between the responsible ministries of the 16 German federal states in common nature conservation issues and to advise the governments of Germany and its federal states correspondingly).

The following paragraphs provide an overview of the goals of the abovementioned projects as well as the methods used.

Project 1:

Development of a system to evaluate the management quality of national parks (2005–2008) [11,12]

This project aimed at developing (1) a quality set of criteria, standards, indicators and questions to be answered by the national park administrations, and (2) the definition of the evaluation process itself, meaning how the evaluation should be conducted. It was based upon different working steps, the results of which were intensively discussed and reviewed in workshops that involved all actors mentioned above. The methods included an analysis of already existing evaluation systems for large protected areas (e.g., UNESCO Biosphere Reserves), the preparation of a draft of the quality set by an expert office commissioned by EUROPARC Germany, the discussion and further development of the draft version in workshops, a pre-test in four national parks and the adoption of the criteria and standards by LANA.

The resulting quality set includes

- a vision of how the national parks would ideally develop, which could serve as a basis for the formulation of the following elements of the quality set;

- “fields of action”, covering all topics and tasks relevant for the fulfillment of national park purposes and achieving the vision;

- quality criteria describing the requirements for the fields of action in detail;

- quality standards depicting the best possible state of each quality criterion;

- a questionnaire with questions and indicators allowing the current state of each standard to be recorded. It consists of several hundred questions and indicators on the criteria and standards, which have to be answered or assessed by the national park administrations.

Table 1 shows the fields of action and criteria. They contain some elements which can also be found in other evaluation systems, e.g., within the PAME common reporting system [4] (see also [5,7]). However, they have also been modified and amended in order to do justice to the specific situation and requirements of national park management in Germany, as pointed out by the national park administrations. For example, the standard for criterion “2.1 Space for natural processes” is as follows: “Over most of their area, national parks protect the dynamics of natural processes with as little disturbance as possible. In general, this is ensured within a period not longer than 30 years after an area has been designated a national park and for at least 75% of the national park area. The areas for the protection of natural dynamic processes should be contiguous or not interrupted, with few outer boundaries”. Criterion 3.5 “Financing” is detailed by the standard “The full financing of the national park is provided by the federal state in each case. The financing covers at least the protection of natural processes, management, supervision of area, maintenance of recreational infrastructure for experiencing nature, contribution to education for sustainable development, monitoring and research, communication, cooperation in the regional development in the national park surroundings as well as general administration. Support by third parties for the goals of the national parks is desirable.” All standards are presented in the Supplementary Materials to this article as well as in several publications by EUROPARC Germany (see [11,12,13,14]).

Table 1.

Fields of action and criteria set for the evaluation of the management quality in national parks in Germany (as of 2008) [11,12,13,14].

Project 2:

First full evaluation of the national parks (2009–2012) [13,14,20]

Between 2009 and 2012, all the existing 14 German national parks were evaluated on a voluntary basis by a special evaluation committee, whose members had been appointed by LANA. The committee consisted of two representatives of the federal government (BMU—German Ministry for the Environment, BfN), four representatives of the federal states, four representatives of Universities, three representatives of non-governmental organizations, two representatives of the National Parks Working Group of EUROPARC Germany, one representative of EUROPARC Germany and, additionally, one staff member of EUROPARC Germany, who was not a member of the committee, but in charge of managing the entire process. On the evaluation visits to the national parks, only one or two representatives of each of the mentioned groups took part, since most committee members worked on a voluntary basis, in addition to their regular jobs, and they were not to be overburdened by the visits, their preparation and the follow-up work. As a consequence, the personnel composition of the evaluation committee varied from park to park.

The evaluation of each national park started with the online completion of the questionnaires by the national park administrations in order to assess the compliance of current management practice with the quality standards. Subsequently, an external office analyzed the filled-out questionnaire and prepared a first draft evaluation report. This draft report served as preparation for the visit of the park by the evaluation committee. This one and a half day visit included a field excursion to points of special interest for the committee, interviews with members of the national park administration to discuss and clarify open questions and a meeting with stakeholders of the national park (e.g., land users, NGOs, public authorities). Shortly thereafter, EUROPARC Germany and the evaluation committee prepared the second draft report, on which the national park administrations and the responsible federal state ministries gave feedback before the final version was completed by EUROPARC Germany and published by the park in agreement with the responsible ministry.

The different steps of the evaluation process are depicted in Table 2. The time frame given refers to one park only. As the evaluation of the parks had to be started in quick succession, different parks had to be assessed in parallel by EUROPARC Germany and the evaluation committee, albeit at different working steps. This led to a considerable effort for both and to a duration of nearly four years of the entire evaluation—from the completion of the questionnaire by the first park to the publication of the evaluation report by the last one.

Table 2.

The evaluation process—step by step.

The main task of the committee was the identification of the extent to which the national parks had already fulfilled the quality standards and to deduce therefrom the strengths and weaknesses of each national park. On this basis, park-specific recommendations had to be given in order to secure the successes which had already been achieved, to improve the weaknesses and management effectiveness in general. The results were presented in the form of an approximately 50-page evaluation report for each national park, which was handed over the national park administrations, the relevant state ministries, the BfN and the BMU. Moreover, all of them had voluntarily been made available to the public via Internet.

It has to be emphasized that the aim of the evaluation was not to rank or rate the national parks against each other. Differences in the natural environment, the human and financial resources of the administrations, the regional environment, age of the parks, culture and land-use history or existing uses in the park, as well as the constitutional federal principle (the federal states are in charge of the national parks), do not allow such a comparison.

To gain an overview of the entire German national park system, a so-called “cross-section evaluation” was carried out and published [13,14], providing an anonymized overview of the evaluation results for all parks. While pursuing this work, some weaknesses of the evaluation method became visible and were documented (see Section 3.2.1 [21]).

Additionally, a final discussion of the evaluation committee and a written survey among the national park administrations provided further information on strengths and weaknesses of the evaluation process. This could be described as an “evaluation of the evaluation” in order to improve the process for following evaluations [22].

Project 3:

Interim evaluation of the national parks (2015–2018) [23]

All actors and institutions involved so far agreed that an interim evaluation after five years and another full evaluation after ten years should be carried out. Thereby, the results of the first full evaluation should be secured and the potential of evaluations could be utilized long-term. Accordingly, an interim evaluation took place between 2015 and 2018. It focused on the implementation of the recommendations made by the evaluation committee in the evaluation reports, i.e., on the progress made in further optimizing the management quality. The interim evaluation was carried out by EUROPARC Germany and supported by a representative of the national parks as well as the former spokesperson of the evaluation committee. The former evaluation committee was not involved, as this would have resulted in an unjustifiably high effort.

The working program consisted of three modules:

- Module 1: Data collection through a written survey and telephone interviews with the national park administrations; writing of a first draft report; review by the national park administrations.

- Module 2: Short workshops in the national parks.

- Module 3: Assessment of progress; writing of second draft report; review and approval by the national park administrations; final report.

The questionnaire for the national park administrations (Module 1) comprised questions on (1) the implementation of the recommendations given by the former evaluation committee; (2) measures that were carried out independently of the recommendations or going beyond them to meet the quality standards and (3) on the effects of the evaluation report and how the administrations made use of it. The workshops (Module 2) served to discuss and refine the results of the written survey and to resolve any open questions. Only the respective national park administration, EUROPARC Germany and a representative of BMU or BfN took part in them; in some cases the responsible ministries or other important stakeholders, invited by the national park administration, attended as well. In Module 3, the results were finally assessed and resubmitted to the national park administration to ensure factual accuracy. Afterwards, the final report was prepared. Again, there are reports for each individual park and a final project report, which compiles the results of all national parks but has not been published to date. The EUROPARC Germany working group on national parks and an external experts’ group, which met twice, supported the project.

Project 4:

Further development of quality criteria and standards for German national parks (2019–2020)

Alongside the numerous positive results, the full and interim evaluation also revealed weaknesses in terms of content and process. These related for example to the consistency of standards and corresponding questions or the high expenditure of time for the national park administrations (detailed explanation in Section 3.1). In addition, over the past 10 years, further requirements for national parks have emerged, which could be taken into account in future evaluations. Therefore, this fourth project, taking place between August 2019 and December 2020, is dedicated to improving the quality set (fields of action, standards, criteria, questions and indicators) and the evaluation process. It must be ensured that the results of different evaluations remain comparable. Hence, the number and content of the new criteria and standards should not differ substantially from the previous ones.

At the beginning of the project, the revision requirements already known from Projects 2 and 3 were systematically compiled in a comprehensive table, which was commented on and supplemented by all national park administrations as well as external experts (BMU, BfN, LANA, University, NGO). The results formed the basis for a two-day workshop in January 2020 with representatives of all national parks, during which the fields of action, criteria and standards were discussed and suggestions for improvement were developed. In further iterative coordination between the project holder and all participants, a new draft version of the quality set, comprising the fields of action, criteria and standards was developed, further discussed, refined and again discussed at a second workshop in June 2020. On this basis, questions and indicators that were no longer necessary were removed from the questionnaire, and new ones were added, if necessary. In upcoming rounds, final changes can be made before the new quality set has to be approved by LANA.

3. Results

The following sections firstly present the results of the full and interim evaluation with regard to the national park management (Section 3.1), and secondly the strengths and weaknesses of the evaluation method itself, as well as necessary improvements for future evaluations derived from it (Section 3.2).

3.1. National Park Management

3.1.1. Results of the First Full Evaluation (2009–2012)

German national parks can differ greatly from each other. During the evaluation, this applied, for example, to the year of foundation (1970–2004), area (3070 ha–441,500 ha), staffing (20 full-time positions–151 full-time positions plus 42 part-time positions), legal responsibilities, natural conditions, existing third-party rights of land use or the options of managing financial resources. Therefore, it is not surprising that the identified strengths and weaknesses of each national park also differed greatly. Nevertheless, common tendencies could be identified which apply to a majority of the national parks, although the situation in individual parks may deviate considerably.

Table 3 gives an overview of important strengths and weaknesses in various fields of action. For example, the increase in the acceptance of the parks by the regional population, which results from numerous activities undertaken by the national park administrations, is to be highlighted positively. On the other hand, however, personnel resources and organizational structure are often inadequate to deal with central tasks.

Table 3.

Main strengths and weaknesses of national parks in Germany according to the first full evaluation, carried out between 2009 and 2012 (the table shows the main tendency; the situation in individual national parks can differ significantly) [13,14].

With regard to the impact of the evaluation process, it is noteworthy that during and because of the evaluation process, the national park administrations had already been intensively addressing topics that previously had not been in their focus. In addition, cross-national park initiatives were initiated, e.g., for wildlife management.

3.1.2. Results of the Interim Evaluation (2015–2018)

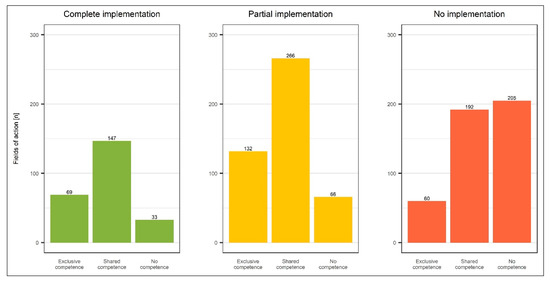

The interim evaluation [23] focused on the implementation of the recommendations given by the evaluation committee during the previous full evaluation and the resulting improvements. In total, for all national parks, the committee had given 1076 recommendations. The number of recommendations per national park ranged from 57 to 95, with an average of 77. By the data collection deadline of the interim evaluation (end of January 2016), 249 recommendations (23%) had been fully implemented, 464 (43%) partially, and 357 (33%) not (Figure 3). The implementation of two thirds of all recommendations had thus begun. Since the partially implemented recommendations include many measures that arise regularly and require ongoing efforts, the actual situation is even more positive than is reflected in the plain figures.

Figure 3.

Results of the interim evaluation of German national parks: Degree of implementation of measures recommended during the full evaluation, depending on the allocation of competence for the respective measure. © Nationale Naturlandschaften e.V.

Figure 3 puts special emphasis on the question of whether the degree of implementation is dependent on the competence for the respective measure. This responsibility can be assigned to the national park administration alone (“Exclusive competence”), to the national administration and other actors (e.g., land owners, public authorities, the respective ministry, NGOs, private educational providers) which have to be involved (“Shared competence”) or to other actors alone (“No competence”). Considering the entirety of all national parks and recommendations, the answer to the above question tends to be “yes”: Whereas 26.4% of all measures in exclusive competence and 24.3% of all measures in shared competence are completely implemented, this applies only to 10.9% of all measures with “no competence” of the national park administration. About three quarters of all measures both in exclusive and shared competence are completely or partially implemented, but only 32% of the measures depend entirely upon the decision of other actors. One reason for this is that other actors do not primarily—or sometimes not at all—pursue the interests of the national park.

However, a different picture emerges when looking at the individual parks. Six parks display the same result as described above—the proportion of implemented recommendations is significantly higher when the park administration has full competence, compared to shared or no competence. However, in three national parks the share of fully implemented measures is completely independent of the allocation of competence, and in five parks the proportion is lower when the park administration has exclusive competence than when it has shared or no competence.

The recommendations covered all fields of action. Examples can be found in Table 4, which shows improvements in park management that were achieved based on the recommendations. In almost all national parks, an above-average number of recommendations was implemented in the field of action “Protection of natural biological diversity and dynamics”. This refers in particular to the increase in the proportion of the nature dynamic zone (eight national parks), the reduction of high hoofed game populations (four national parks) and the success in, or reduction of, forest development measures (three national parks).

Table 4.

Examples for the improvements in park management achieved by the first full evaluation of German national parks [23].

In addition, several national park administrations implemented an above-average number of recommendations in the fields of action “management”, “communication”, “education”, “nature experience and recreation” as well as “monitoring and research”. This concerned, for example, the reduction or restriction of usage rights, the further development of socio-economic monitoring, the improvement of communication and external presentation of the national park as well as the expansion of offers for education and nature experience, including barrier-free offers.

On the other hand, the recommendations for the fields of action “framework conditions” and “organization” have been relatively poorly implemented—although they are of central importance for the work of a national park administration, since they significantly influence the possibilities in other fields of action. However, improvements in these two fields of action are often difficult to achieve by the national park administrations, because in many cases either other actors, such as parliaments and different ministries of the federal states, or the national government and subordinate authorities hold the necessary decision-making powers, or legal, political and financial limits are predetermined for the national park administrations.

In every national park there are still deficits, which vary in number and severity and can occur in all fields of action. In particular, recommendations that required strong cooperation between different authorities or the amendment of laws and regulations could not be implemented in most cases. Lack of land ownership by the federal states and high costs also proved to be serious obstacles to implementation. Remaining weaknesses in the Fields of action 1–4 must be regarded as particularly significant, since they can either have decisive effects on other fields of action or impair the central purpose of protection.

For example, concerning field of action 1, “Framework conditions”, not all national park administrations have the necessary regulatory responsibilities for the full realization of the national park’s objectives. Regarding field of action 2, “Protection of natural biological diversity and dynamics”, it is still not clear how some national parks can achieve the 75% share of the natural dynamics zone within 30 years after their foundation. One obstacle here is the management of high hoofed game populations, which is partly still carried out in nature dynamic zones. Forest development measures, which are too strongly oriented toward regular forestry, also play a role. Furthermore, still existing usage rights, which are difficult to abolish (or only in the long run), impair the realization of the protection purpose in many national parks. Lastly, four national parks still do not reach the internationally envisaged minimum size of 10,000 ha.

Already during the first evaluation, the insufficient quantitative and/or qualitative staffing, which may also include national park rangers, was identified as a fundamental problem of almost all national parks. This problem still persists, albeit with varying intensity—the number of employees ranges from about 20 to almost 200. Even in better equipped national parks it happens that some positions cannot be filled at all, or only with staff lacking the necessary qualifications. In addition to the organizational structure, staffing, however, is a crucial factor in maintaining the successes achieved and remedying any remaining deficits.

3.2. Evaluation Method and Process

3.2.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Evaluation Method and Process

The interim evaluation proved that the full evaluation had initiated and promoted important changes, and thus provided a major impetus for the improvement of the management quality in all German national parks. In addition, the evaluation achieved its secondary goal of highlighting the national park administrations’ strengths and weaknesses from an external perspective, giving advice and further supporting their work. As the National Parks Working Group of EUROPARC Germany confirmed, an unbiased view and constructive criticism from the outside are important and helpful, both internally and with regard to external relationships and the presentation of a national park [23]. LANA and the responsible ministries also unanimously supported a continuation of the evaluation.

The strengths of the evaluation method can be summarized as follows:

- a quality set that is well oriented toward the tasks and problems of the parks and therefore generally accepted by the parks and the federal states;

- numerous opportunities to discuss uncertainties of the evaluation results (e.g., by inquiries to the parks by EUROPARC or workshops in the parks) and therefore avoid misunderstandings;

- involvement of a multidisciplinary external evaluation committee that contributes additional expertise and an outside perspective;

- visits to the national parks which allow for detailed on-site surveys and discussions;

- the possibility for the parks to give feedback on the draft evaluation report in order to correct factual mistakes and potential misrepresentations.

However, the full and interim evaluation have also shown that the quality set and the evaluation process need to be revised and further developed. In the following, the main reasons for this in terms of content and process are listed [21,22] (for comparison, see [24,25]).

Weaknesses of the quality set

- Unclear delimitation between fields of action due to individual criteria; e.g., criterion “Integration of the national park into the region”, in field of action 4, “Management” vs. field of action 10, “Regional development”.

- Redundancies at the levels of fields of action and criteria; e.g., questions/statements on the protection of natural dynamics in fields of action 2 and 4, on the integration of the national park into the region in fields of action 4, 5 and 10, on naturalness in criteria 1.6, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3.

- Missing fit between field of action and corresponding criteria or criteria and corresponding standard: In some cases, the standards and questions are not stringently derived from the corresponding criteria and standards, resulting in an incomplete compatibility between the three levels. This leads to some contents of the standard not being covered by questions, while the associated questions go beyond the standard in other places. As a consequence, the three offices which had written the first draft of the committee reports during the full evaluation emphasized different aspects, and the committee, consisting of a different combination of members in each park, adopted them in different ways. For example, in the case of several criteria, it is asked whether the national park administration has a written concept without this being required by the standard (e.g., criteria 2.5, Species Management, 2.6, Ecosystem Networking, 3.4, Human Resources Management). In such cases, it is unclear or left to the committee how to assess the lack of the concept. This could lead, at least slightly, to different assessments of the parks.

- A few standards are partly formulated in a rather qualitative or “soft” way, as for example in the standard for criterion 7.3: “The staff members … emanate a sense of identification with the national park”. Such standards cannot be operationalized and verified without considerable effort. This results in a lack of valid ascertainability.

- The number of questions and indicators that have to be answered or collected by the national park administrations is regarded as too high and time-consuming—a point that has been especially emphasized by the park administrations themselves.

- The central objective of national parks is to enable natural dynamic processes without human interference on at least 75% of their area (“Let nature be nature”). The operationalization of this goal requires an understanding of what “natural processes” or “near-naturalness” means in a concrete case and how these desired states can be achieved. This becomes a problem especially in the following situations:

- (a) Further development of currently strongly culturally influenced habitats, especially monoculture, non-natural pine or spruce forests: The national park administrations have to choose between intervening in “natural processes” over a certain period of time, by felling the trees and fostering other, more “natural” species (such as beeches) through active restoration measures, and no longer intervening, thus accepting a “non-natural habitat” for a possibly very long period of time.

- (b) A similar problem exists due to a frequently too high density of hoofed game, which can lead to considerable peeling and browsing damage and thus impede or even prevent natural regeneration. The choice the national park administrations have to face here is either to reduce hoofed game by hunting measures (which is another interference) or to do nothing, which makes it difficult for a new (near-) natural type of forest to develop naturally.

- The national park administrations follow different strategies in both cases described [14,26], which per se can neither be regarded as “good” nor “bad”, providing different answers to the question “What kind of nature do we want to protect?”. The lack of definition of important terms such as “dynamic natural processes”, “near-naturalness” or “wildlife management” in the quality set made a uniform understanding difficult and was one reason for different assessments of similar situations in different national parks. Regarding the actual decisions and activities of the national park administrations, they also have to be based upon financial possibilities and likely effects of the chosen management measures on the acceptance of the national parks within the surrounding region and by important actors. Against this background, the motto “Let nature be nature”, which appears to be very clear and unambiguously realizable at a first glance, proves to be a central challenge on culturally shaped areas and in the midst of a still densely populated and intensively used cultural landscape. This has an impact on all management decisions and the public effectiveness and acceptance of national parks [14]. It is difficult to answer this question uniformly for all parks. In its new position paper, the National Parks Working Group of National Natural Landscapes e.V. justifies wildlife regulation in national parks as a specific instrument of species management if natural regulatory factors do not have a sufficient effect; however, it should be used “as little as possible” [27].

- More than a decade has passed since the quality set was developed. Therefore, it does not or only insufficiently reflect current developments, which have become increasingly apparent in recent years. These include topics such as wilderness, socio-economic monitoring, ecosystem services, international cooperation, accessibility and inclusion, climate change or a role model function of national park administrations with regard to sustainable management.

Weaknesses of the evaluation process

- Both the initial and interim evaluation required a great deal of time and personnel in addition to the “day-to-day work” that had to be done. These expenditures proved to be problematic and unsatisfactory, especially for the national park administrations.

- This is related to the long duration of the evaluations. From the start of the data collection to the completion of the last evaluation report, the full evaluation and the interim evaluation took about four years and two and a half years, respectively. The reasons for this were the high number of participants (EUROPARC Germany, national park administrations, responsible ministries of the federal states, LANA, BfN, BMU, Universities, NGOs) and a high demand for mutual enquiries and feedback in order to avoid misinterpretations and factual mistakes. Consequently, the reports for the individual national park do not necessarily represent the current status.

Project 4, “Further development of quality criteria and standards for German national parks” addresses these problems and pursues the objectives of

- revising the quality set from the fields of action down to the individual questions of the questionnaire in order (1) to eliminate the abovementioned weaknesses and thereby to obtain more consistent and clearer evaluation results, (2) to minimize the number of questions in order to reduce the time required, and (3) to nevertheless ensure that the results of future evaluations are still comparable to the results of previous ones,

- improving the future evaluation process in terms of effectiveness and efficiency.

The results achieved so far (as of the end of June 2020) are presented in the following section.

3.2.2. The Revised Quality Set and Evaluation Process—Current State

The discussion on the quality set led to an interim version by June 2020, which reduced the number of fields of action from 10 to 8 and the number of criteria from 44 to 41. A combination of closely related former fields of action has been discussed, namely to combine “Cooperation and partners” and “Regional development” to “Cooperation and sustainable regional development” as well as “Education” and “Experiencing nature, recreation” to “Education and nature experience”. It was proposed that some criteria be shifted to other fields of action to avoid redundancies and to give a clearer structure to the quality set: e.g., “Volunteer management” from “Cooperation and partners” to “Organization”, which would then include all personnel topics, or “Integration of the national park into the region” from “Cooperation and partners” to “Management”. According to the current state of the discussion, the field of action “Protection of natural biological diversity and dynamics” would be reduced considerably—not due to a “low” relevance of a topic that is actually very important, but due to many previously existing redundancies. Furthermore, some new criteria have been suggested for integration into the quality set, as they reflect important developments that have taken place throughout the last decade. This is the case of “Environmental management and sustainable procurement”, emphasizing the role model function of a national park; “Participation”, fostering public participation and meeting raised requirements for it; and “Accessibility for and inclusion of handicapped people” to meet the social responsibility of national parks. This is still an interim result or draft, as the entire quality set is subject to further discussion and must be approved by the LANA.

The adaptation of the questions and indicators to the reformulated or new criteria has already begun but is still in progress and has to be completed until the end of the project. Special attention has to be paid to a clear relation to the corresponding standard; the avoidance of mere qualitative statements (“x is in very good, good, rather bad, bad condition”), which can be interpreted differently and therefore also be easily questioned; the possibility of using questions and indicators which are recorded by the Integrative Monitoring of large protected areas, that has been developed in parallel; the reduction of the number of questions, to relieve the national park administrations from as much work as possible. The current status suggests that the number of questions could be reduced by about 20–25%. The updated quality set, including the questionnaire, will be published in 2021 in German and English.

So far, no final decisions have been made concerning the future evaluation process. However, it is clear that no interim evaluation will take place in the future—although it has been of great value to the whole process so far, as it allowed us to review the process and to confirm the importance and achievements of the full evaluation. The next full evaluation is planned to start in 2021 or 2022. How the evaluation committee will then be composed, how the members can develop a common understanding of the evaluation and the quality set and what tasks they will perform also remains to be determined.

4. Discussion

As demonstrated above, the first quality set and its application already led to important findings and contributed to a further improvement in the work of the national park administrations. It is particularly worth mentioning that the evaluation process led to further research projects and initiatives to standardize management practices in national parks, such as the management of hoofed game [26], alien species [28] or the preparation of national park plans [29]. Furthermore, the quality set as well as the evaluation process attracted international interest, e.g., at the COP 11 of the CBD in Hyderabad/India in 2012. In 2014, EUROPARC Germany was commissioned by the Austrian national parks to evaluate them with a similar quality set and approach, but tailored to the specific needs in Austria [6].

All this proves that the quality set and procedure described here can be useful for national parks in other countries, especially since they are based on the international framework for evaluation of protected area management effectiveness by the World Commission of Protected Areas (WCPA). More recent IUCN initiatives moving toward an IUCN Green List of protected and conserved areas [30] could also benefit from the experience gained during the evaluations of German national parks. Such transfers must of course take into account the respective national framework conditions, especially in terms of legal basis, financial support and natural conditions.

Finally, we would like to give some recommendations for the most important aspects to be considered—according to our individual experience.

- Foremost, the evaluation should not be misunderstood by participating actors as an instrument of control and benchmarking, but as a means of support for the national park administrations to fulfill their tasks more effectively and efficiently. This does not mean that points worthy of criticism should not be criticized—on the contrary, but the criticism should be constructive and provided with mutual respect. Only then can an open discussion on critical points be held.

- The evaluation is not a purpose in itself, but serves to support the national parks. It should therefore be as comprehensive as necessary, but also as concise as possible not to overburden the involved parties in terms of time. This includes a clear definition and understanding of what the important aspects of national park management are.

- The evaluation criteria and the evaluation process should be developed together with the national park administrations, so that their experiences and needs can be adequately taken into account from the very beginning. This also makes sense because the rather extensive evaluation process depends heavily on the cooperation of the national park administrations.

- It should be clarified very early on who is in charge of conducting the evaluation and which actors are to be involved at what point in the evaluation process and for what purpose. A clear assignment of standards to fields of action is as indispensable as a logical and stringent derivation of suitable questions from the standards. Redundancies should be avoided.

- Sufficient time should be provided for further inquiries and the clarification of open questions and misunderstandings.

- All participants, especially the members of the evaluation committee (if there is one) should have the same or at least a very similar understanding of the concrete meaning of the central terms and purposes of national parks, such as “natural dynamics”, “natural processes”, “naturalness” or “wilderness”. This is especially true in parks that are surrounded by an intensively used cultural landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/17/7135/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., A.M. and V.S.; methodology, S.H., A.M. and V.S.; investigation, S.H., A.M. and V.S.; data curation, S.H. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H., A.M. and V.S.; visualization S.H., A.M., V.S. project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, A.M., V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Ministry of the Environment (BMU) and professionally accompanied by the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) in the following research and development projects: Entwicklung von Qualitätskriterien und -standards für deutsche Nationalparke (Development of quality criteria and standards for German national parks; FKZ: 80581002), Anwendung von Qualitätskriterien und -standards zur Evaluierung der deutschen Nationalparke (Application of quality criteria and standards for the evaluation of German national parks; FKZ: 3508820200), Zwischenevaluierung deutscher Nationalparke inkl. Analyse zum Artenmanagement in den Kernzonen (Interim evaluation of German national parks incl. analyses on species management in core zones; FKZ: 3515850600), Weiterentwicklung der Qualitätskriterien und-standards für deutsche Nationalparke (Further development of quality criteria and standards for German national parks; FKZ: 3519810600).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of Technische Universität Berlin for the publication of this paper. We would also like to thank Annika Miller for the English proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations: Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/convention/text/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Secretariat of the Convention of Biological Diversity. Programme of Work on Protected Areas. 2004. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/pa-text-en.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Hockings, M.; Stolton, S.; Leverington, F.; Dudley, N.; Courrau, J. Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing Management Effectiveness of Protected Areas, 2nd ed.; Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 14; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leverington, F.; Costa Lemos, K.; Pavese, H.; Lisle, A.; Hockings, M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leverington, F.; Kettner, A.; Nolte, C.; Marr, M.; Stolton, S.; Pavese, H.; Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Hockings, M. Protected Area Management Effectiveness Assessments in Europe; Supplementary Report: Overview of European Methodologies; BfN-Skripten: Bonn, Germany, 2010; Volume 271b, p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Nationalparks Austria; EUROPARC Deutschland; Institut für Ländliche Strukturforschung. Gesamtbericht über die Evaluierung der Nationalparks in Österreich; Berlin, Germany, 2015; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, C.; Leverington, F.; Kettner, A.; Marr, M.; Nielsen, G.; Bomhard, B.; Stolton, S.; Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Hockings, M. Protected Area Management Effectiveness Assessments in Europe; A Review of Application, Methods and Results; BfN-Skripten: Bonn, Germany, 2010; Volume 271a, p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Scherfose, V. Quality Criteria and Standards for Large-Scale Protected Areas in Germany as a Base for Evaluation Processes. 2013. Available online: https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/MDB/documents/service/ZGF_Scherfose_2013_PA_Evaluation.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Coad, L.; Leverington, F.; Burgess, N.; Cuadros, I.; Geldmann, J.; Marthews, T.; Mee, J.; Nolte, C.; Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Vansteelant, N.; et al. Progress towards the CBD protected area management effectiveness targets. Parks 2013, 19, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, P.; Dubois, G.; Dudley, N.; Ervin, J.; Ferrier, S.; Gidda, S.; MacKinnon, K.; Richardson, K.; Schmidt, M.; Seyoum-Edjigu, E.S.; et al. Editorial Essay: An update on progress towards Aichi biodiversity target 11. Parks 2019, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. (Ed.) Quality Criteria and Standards for German National Parks; Developing a Procedure to Evaluate Management Effectiveness; EUROPARC Deutschland e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Available online: http://www.europarc-deutschland.de/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2008_Quality_criteria_and_standards_for_German_national_parks.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. (Ed.) Qualitätskriterien Und-Standards für Deutsche National Parke; Entwicklung eines Evaluierungsverfahrens zur Überprüfung der Managementeffektivität; EUROPARC Deutschland e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. (Ed.) Evaluation of German National Parks; Checking Management Efficiency; EUROPARC Deutschland e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. (Ed.) Managementqualität Deutscher National Parks; Ergebnisse der ersten Evaluierung der Deutschen Nationalparks; EUROPARC Deutschland e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://www.landschaft.tu-berlin.de/menue/publikationen/#c506271 (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Scherfose, V.; Riecken, U.; Jessel, B. Weitere Nationalparke für Deutschland?! Argumente und Hintergründe mit Blick auf die aktuelle Diskussion um die Ausweisung von Nationalparken in Deutschland; Positionspapier des BfN: Bonn, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://www.bfn.de/ueber-das-bfn/positionspapiere.html (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Panek, N.; Kaiser, M. Ein neues Nationalparkprogramm für Deutschland. Nat. Landsch. 2015, 47, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-021.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Scherfose, V. Stand der Entwicklung deutscher Nationalparke. Naturschutz u. Biol. Vielfalt 2009, 72, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit. Nationale Strategie zur Biologischen Vielfalt; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit: Berlin, Germany, 2007; Available online: http://www.biologischevielfalt.de/fileadmin/NBS/documents/broschuere_biolog_vielfalt_strategie_bf.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Heiland, S.; Hoffmann, A. Erste Evaluierung der deutschen Nationalparks: Erfahrungen und Ergebnisse. Nat. Landsch. 2013, 88, 303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Heiland, S. Schwächen der Evaluierung deutscher Nationalparks im Rahmen des F+E-Vorhabens Anwendung von Qualitätskriterien und-standards zur Evaluierung der deutschen Nationalparke. Unpublished Internal Working Paper. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. Evaluierung des Projekts Anwendung von Qualitätskriterien und-standards zur Evaluierung der deutschen Nationalparke. Unpublished Internal Working Paper. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EUROPARC Deutschland e.V. Zwischenevaluierung der Deutschen Nationalparks Inklusive Analyse zum Artenmanagement in den Kernzonen (insbesondere Neobiota); Abschlussbericht über das Teilprojekt Zwischenevaluierung des F+E-Vorhabens des Bundesamtes für Naturschutz; Berlin, Germany, 2019; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, C.N.; Hockings, M. Opportunities for improving the rigor of management effectiveness evaluations in protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 2011, 4, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Dudley, N.; Belokurov, A.; Deguignet, M.; Burgess, N.D.; Hockings, M.; Leverington, F.; MacKinnon, K.; Young, L. Lessons learned from 18 years of implementing the Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool (METT): A perspective from the METT developers and implementers. Parks 2019, 25, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, S.; Lang, J.; Simon, O.; Hohmann, U.; Stier, N.; Nitze, M.; Heurich, M.; Wotschikowsky, U.; Burghardt, F.; Gerner, J.; et al. Wildmanagement in Deutschen Nationalparken; BfN-Skripten 434; Bonn-Bad: Godesberg, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/BfN/service/Dokumente/skripten/Skript434.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Nationale Naturlandschaften, e.V. AG Nationalparke: Positionspapier Wildtierregulierung. Unpublished. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, J.R.; Schmiedel, D.; Scherfose, V.; von Oheimb, G. Umgang mit Neobiota und Zielarten in Naturdynamik- und Entwicklungszonen deutscher Nationalparks. Nat. Landsch. 2019, 94, 472–483. [Google Scholar]

- Schlumprecht, H.; Knuff, A.; Scherfose, V. Vorschläge zur Gliederung und zu Inhalten von Nationalpark-Plänen; Leitfaden des BfN; BfN-Skripten 425; Bonn-Bad: Godesberg, Germany, 2015; Available online: https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/BfN/service/Dokumente/skripten/Skript425.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Hockings, M.; Hardcastle, J.; Woodley, S.; Sandwith, T.; Wildson, J.; Bammert, M.; Valenzuela, S.; Chataigner, B.; Lefebvre, T.; Leverington, F.; et al. The IUCN green list of protected and conserved areas: Setting the standard for effective area-based conservation. Parks 2019, 25, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).