Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Research Ethics

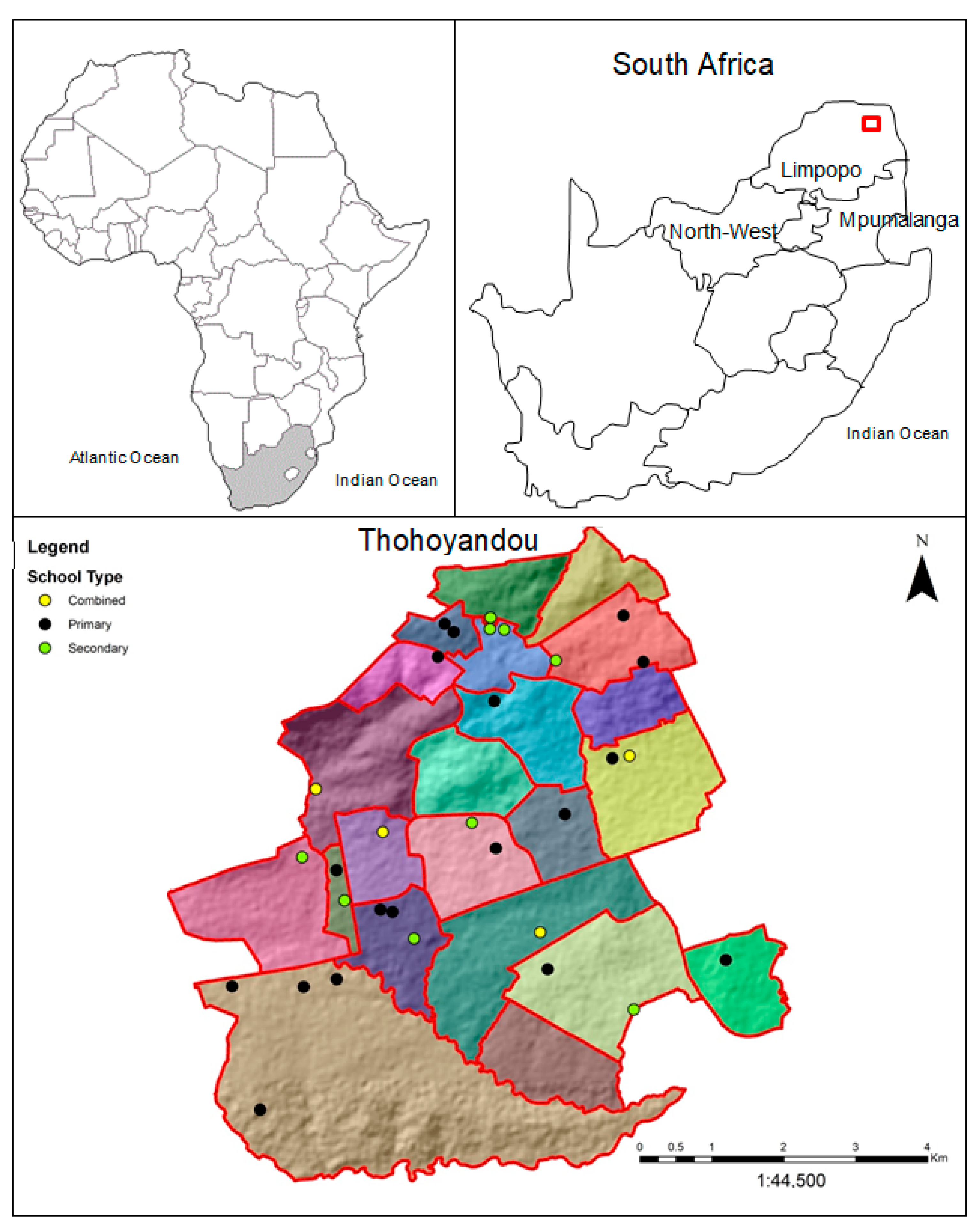

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

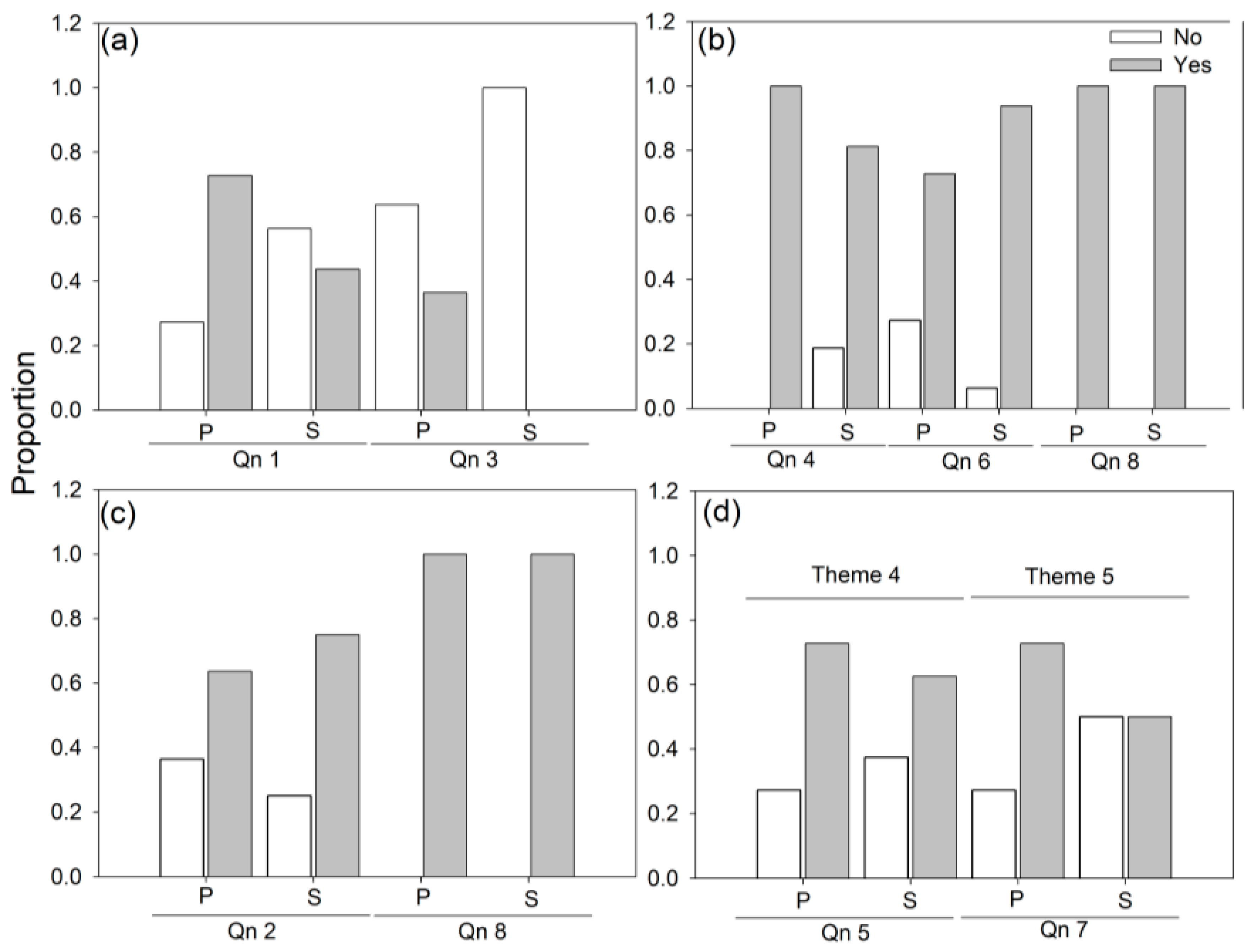

3.1. School Environmental Policies and Code of Conduct

“Secondary School B, Deputy-principal: Yes, learners are not allowed to throw rubbish everywhere because we have rubbish bins in front of every class. On Wednesdays, rubbish from the bins must be collected. There are dire consequences if a learner is found littering in school grounds.”

“Secondary, School B, Senior Teacher A: Yes, do not litter, there are also posters that encourage learners not to throw litter around and trees should be protected as they create a healthy and clean air environment.”

“Primary School A, Teacher C: Yes, learners are reminded to pick any plastics and other materials and throw them in the dustbins.”

“Primary School B, Senior Teacher A: Yes, keep the environment safe by not littering in the school grounds. For instance, burning of plastics and other materials is done after school hours when learners are not present to protect them from inhaling smoke as it will pose a health threat to them.”

3.2. Education and Awareness

- (a)

- General school rule;

“Primary School A, principal…early in the morning, learners pick up plastics and dirty materials and throw them in the dust bins”

- (b)

- form of punishment;

“Primary School C, Teacher A…late comers pick litter in school grounds”

- (c)

- form of incentive;

“Primary School A, Teacher C …last year there was a competition where learners challenged each other on keeping the school free of plastic and papers. In addition, the classes that won were foundation phase classes which start from grade R to grade 3”

- (d)

- collaboration with solid waste-preneurs;

“Primary School B, Teacher B…there are people who come with bicycle carts to collect plastic materials and in turn send them for recycling in exchange for money”.

“Secondary School B, Teacher A…there is Limpopo Green Schools for the Earth which is a four-year program whereby learners and communities are part of it. It encourages people to protect water resources as most of the improperly managed plastics end up in rivers”.

“Primary School A, Teacher A…dustbins are provided in the school yard so that plastics don’t end up in the ground.”

“Secondary School, Teacher C…there are plenty dustbins around the school and are classified on what waste is disposed.”

“Secondary School A, d/principal… the school has bought bins but learners lack interest on the issue of throwing litter in the bins. The reason behind is that they expect cleaners to pick up the litter as it is part of their jobs.”

“Primary School C, d/principal…because we are living in a dirty environment, so we should alert learners on the dangers of plastics as it may harm them in one way or the other. For instance, children might cover their faces with plastic and end up suffocating thus dying.”

“Primary School C, Teacher A…because plastics have been a global problem which results in death of birds, fish and livestock”.

“Secondary School B, Teacher C…it is important because locally people burn plastics and other waste which releases dangerous gases that harm human health. Inhalation of gases released contributes to diseases such as asthma and lung diseases. In addition, burning of waste also adds the amount of heat in the environment which results in global warming.”

“Secondary School C, Teacher A…there are dustbins and a site where plastics and other waste are burnt.”

3.3. Curriculum Development

“Primary school A, Teacher C:Yes, in grade 7 there is a topic of matter and materials whereby learners are taught about the manufacturing of plastics and the environmental impacts they have on the environment.”

“Secondary school C, deputy principal:Yes, it is vital to ensure a green footprint, however, teachers do address the dangers of pollution, yet they (the teachers) litter daily…”

3.4. Stakeholder Partnerships

“Secondary School C, Deputy Principal: Yes, there is Thohoyandou Victim Empowerment Programme (TVEP) that raises awareness on social problems and are addressing environmental problems. For instance, improper disposal of disposable nappies has impact on the environmental and human well-being as it ends up on roads and nearby rivers.”

3.5. Resource Availability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettipas, S.; Bernier, M.; Walker, T.R. A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic marine pollution. Mar. Policy 2016, 68, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, J.; Bond, A.L.; Avery-Gomm, S.; Borrelle, S.B.; Bravo Rebolledo, E.L.; Lavers, J.L.; Mallory, M.L.; Trevail, A.; Van Franeker, J.A. Quantifying ingested debris in marine megafauna: A review and recommendations for standardization. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.; An, Y.J. Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T.; Malesa, B.; Cuthbert, R.N. Assessing factors driving the distribution and characteristics of shoreline macroplastics in a subtropical reservoir. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amélineau, F.; Bonnet, D.; Heitz, O.; Mortreux, V.; Harding, A.M.; Karnovsky, N.; Walkusz, W.; Fort, J.; Gremillet, D. Microplastic pollution in the Greenland Sea: Background levels and selective contamination of planktivorous diving seabirds. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R. Prospect of recycling of plastic product to minimize environmental pollution. Encycl. Renew. Sustain. Mater. 2018, 1, 695–703. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.K.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, R.N.; Al-Jaibachi, R.; Dalu, T.; Dick, J.T.; Callaghan, A. The influence of microplastics on trophic interaction strengths and oviposition preferences of dipterans. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2420–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbedzi, R.; Dalu, T.; Wasserman, R.J.; Murungweni, F.; Cuthbert, R.N. Functional response quantifies microplastic uptake by a widespread African fish species. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavropoulos, A.; Newman, D. Wasted Health: The Tragic Case of Dumpsites; Report Prepared as a Part of International Solid Waste Association’s Scientific and Technical Committee Work-Program 2014–2015; International Solid Waste Association: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, N.; Kumar, A.; Majgi, S.M.; Kumar, G.S.; Prahalad, R.B.Y. Usage of plastic bags and health hazards: A study to assess awareness level and perception about legislation among a small population of Mangalore city. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, LM01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvergne, P. Why is the global governance of plastic failing the oceans? Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 51, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.W.M.; Chow, S.C.F. Environmental education in primary schools: A case study with plastic resources and recycling. Education 3-13 2019, 47, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizmony-Levy, O. Bridging the global and local in understanding curricula scripts: The case of environmental education. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2011, 55, 600–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Thondhlana, G. Plastic bag use in South Africa: Perceptions, practices and potential intervention strategies. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L.; Maricchiolo, F.; Carrus, G.; Dumitru, A.; Mira, R.G.; Stancu, A.; Moza, D. Environmental considerations in the organizational context: A pathway to pro-environmental behaviour at work. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Yeung, K.L.; Carrico, A.R.; Gillis, A.J.; Raimi, K.T. From plastic bottle recycling to policy support: An experimental test of pro-environmental spillover. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, C.C.; Cheung, T.Y.; So, W.W.M.; Cheng, I.N.Y.; Fok, L.; Yeung, C.H.; Chow, C.F. Enhancing pupils’ pro-environmental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours toward plastic recycling: A quasi-experimental study in primary schools. In Environmental Sustainability and Education for Waste Management; So, W., Chow, C., Lee, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyamin, A.; Djuwita, R.; Ashar, A.A. Norm activation theory in the plastic age: Explaining children’s pro-environmental behaviour. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 74, 08008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.E.; Rickson, R.E. Environmental knowledge and attitudes. J. Environ. Educ. 1976, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molstad, E.P.; Heyer, K.P.; Martin, K.; Sardi, P. Reducing single-use plastic in a thai school community: A sociocultural investigation in Bangkok, Thailand. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/206 (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Van Rensburg, M.L.; S’phumelele, L.N.; Dube, T. The ‘plastic waste era’; social perceptions towards single-use plastic consumption and impacts on the marine environment in Durban, South Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 114, 102132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Census 2016: Achieving a Better Life for All: Progress Between Census’ 2007and Census 2016 (No. 3); Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczyk, G.; De Matteo, D.; Festinger, D. Essentials of Research Design and Methodology; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. Research Designs; Cooper, H., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopaedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Release 16.0.0 for Windows. Polar Engineering and Consulting; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adane, L.; Muleta, D. Survey on the usage of plastic bags, their disposal and adverse impacts on environment: A case study in Jimma City, Southwestern Ethiopia. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2011, 3, 234–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chanthawong, A.; Dhakal, S.; Kuwornu, J.K.; Farooq, M.K. Impact of subsidy and taxation related to biofuels policies on the economy of Thailand: A dynamic CGE modelling approach. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018, 11, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, C.; Feng, L. Environmental governance strategies in a two-echelon supply chain with tax and subsidy interactions. Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 290, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.N.; Royals, A.W.; Jameel, H.; Venditti, R.A.; Pal, L. Evaluation of paper straws versus plastic straws: Development of a methodology for testing and understanding challenges for paper straws. BioResources 2019, 14, 8345–8363. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, A.; Simpson, A.; Neeman, T.; Dickson, K. Plastic bag bans: Lessons from the Australian Capital Territory. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, I.; Thomas, S.M. Making sense with posters in biological science education. J. Biol. Educ. 1999, 33, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursitasari, I.D.; Suhardi, E.; Fitriana, I. Development of context-based teaching book on environmental pollution materials to improve critical thinking skills. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Human Res. 2019, 253, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, K.P.; Chan, H.W. Environmental concern has a weaker association with pro-environmental behaviour in some societies than others: A cross-cultural psychology perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M. Mitigating Microplastics: Development and Evaluation of a Middle School Curriculum. Master’s Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T.R.; Pettipas, S.; Bernier, M.; Xanthos, D.; Day, A. Canada’s Dirty Dozen: A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic pollution. Zone Fall Coast. Zone Can. Assoc. Newsl. 2016, 9–12. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tony_Walker/publication/311732880_Canada\T1\textquoterights_Dirty_Dozen_A_Canadian_policy_framework_to_mitigate_plastic_marine_pollution/links/5858032608aeabd9a589e1b5/Canadas-Dirty-Dozen-A-Canadian-policy-framework-to-mitigateplastic-marine-pollution.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Karpudewan, M.; Roth, W.M. Changes in primary students’ informal reasoning during an environment-related curriculum on socio-scientific issues. Inter. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2018, 16, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.M. Environmental Engagement through Behaviour Change Interventions: A Case Study of Litter Reduction in New Zealand Schools. Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kanene, K.M. The impact of environmental education on the environmental perceptions/attitudes of students in selected secondary schools of Botswana. Eur. J. Altern. Educ. Stud. 2016, 1, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.; Vinoda, K.S.; Papireddy, M.; Gowda, A.N.S. Toxic pollutants from plastic waste—A review. Proc. Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essienubong, I.A.; Okechukwu, E.P.; Ejuvwedia, S.G.; Essienubong, I.A.; Okechukwu, E.P.; Ejuvwedia, S.G. Effects of waste dumpsites on geotechnical properties of the underlying soils in wet season. Environ. Eng. Res. 2018, 24, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, H.M. Medical school curricula should highlight environmental health. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.B. Evaluating Environmental Education in Schools. A Practical Guide for Teachers; Environmental Education Series 12; Environmental Education Section, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gayford, C. Environmental education in schools: An alternative framework. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 1996, 1, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, A.N.H. Plastic bags and environmental pollution. Art Educ. 2010, 63, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanišić, J.; Maksić, S. Environmental education in Serbian primary schools: Challenges and changes in curriculum, pedagogy, and teacher training. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.; El Batri, B.; Zaki, M.; Nafidi, Y. Environmental education in Moroccan primary schools: Promotion of representations, knowledge, and environmental activities. Elem. Educ. Online 2019, 19, 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, P.; Fernandes, R.C. Bibliographic review of articles on pedagogical practice of environmental education in schools. Terrae Didat. 2019, 14, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, E.; Edge, A.; West, A. Environmental Education in the Educational Systems of the European Union: Synthesis Report. Available online: http://www.medies.net/_uploaded_files/ee_in_eu.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- MacDonald, A.; Clarke, A.; Huang, L.; Roseland, M.; Seitanidi, M.M. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG# 17) as a means of achieving sustainable communities and cities (SDG# 11). In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kandziora, J.H.; Van Toulon, N.; Sobral, P.; Taylor, H.L.; Ribbink, A.J.; Jambeck, J.R.; Werner, S. The important role of marine debris networks to prevent and reduce ocean plastic pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannathoko, M.C. School-stakeholder-partnership enhancement strategies in the implementation of arts in Botswana basic education. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2019, 15, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. The relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental attitude of high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 1999, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Collaboration as a Pathway for sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 16, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Question | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Are There Any Environmental Policies in the School that You are Aware of? | 1 |

| 2 | Within the curriculum is there any content that allows you to teach about pollution and specifically plastic pollution? | 3 |

| 3 | Are there any banned plastics in the school? | 1 |

| 4 | Are there any extra curricula activities or programs that increase environmental awareness such as picking up litter around the school of recycling? | 2 |

| 5 | Does the school have any networks with NGO’s that promote environmental awareness? | 4 |

| 6 | Are there any resources (i.e., environmental awareness posters, flyers) allocated towards environmental education? | 2 |

| 7 | Do teachers consciously choose to use non plastics materials when they are teaching? | 5 |

| 8 | Do teachers feel it is important to teach about pollution and the specific dangers to the environment? | 3 |

| Principal | Deputy Principal | Senior Teacher | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||

| Primary | |||||

| A | x | x | x | x | x |

| B | x | x | |||

| C | x | x | x | x | |

| Secondary | |||||

| A | x | x | x | x | x |

| B | x | x | x | x | |

| C | x | x | x | x | x |

| D | x | x | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dalu, M.T.B.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Muhali, H.; Chari, L.D.; Manyani, A.; Masunungure, C.; Dalu, T. Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176775

Dalu MTB, Cuthbert RN, Muhali H, Chari LD, Manyani A, Masunungure C, Dalu T. Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176775

Chicago/Turabian StyleDalu, Mwazvita T. B., Ross N. Cuthbert, Hulisani Muhali, Lenin D. Chari, Amanda Manyani, Current Masunungure, and Tatenda Dalu. 2020. "Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176775

APA StyleDalu, M. T. B., Cuthbert, R. N., Muhali, H., Chari, L. D., Manyani, A., Masunungure, C., & Dalu, T. (2020). Is Awareness on Plastic Pollution Being Raised in Schools? Understanding Perceptions of Primary and Secondary School Educators. Sustainability, 12(17), 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176775