Abstract

Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) is an inclusive approach to the research and innovation process. Regional and local authorities are encouraged to take advantages of RRI in order to address the complexity of the interplay between science and society, especially as it affects territorial development policies. However, adopting the RRI approach is not an immediate or linear process. Consciously or not, many territories have already adopted policies and planning instruments that incorporate RRI, generating effects on the spatial scales. The aim of this study is to provide a methodology to map the inclusion of RRI dimensions (i.e., public engagement, open access, gender, ethics, science education) into regional development policies and spatial planning instruments, in order to detect integrated strategies and elements that are sustainable, open, inclusive, anticipative and responsive. The mapping methodology has been applied to three territorial pilot cases. The results provide the territories with a baseline to improve the integration of the RRI approach in their commitments to develop self-sustaining research and innovation ecosystems. Through the lessons learnt from the pilot cases, recommendations are drawn for the integration of RRI in spatial and urban planning policies and tools.

1. Introduction

The term ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’ (RRI) appeared for the first time in Europe around 2011 during the drafting of the Horizon 2020 Framework Program [1], as the evolution of the term ‘Responsible Research’ employed in 2002 in the 6th Framework Program [2] and used to foster ethical issues and the dialogue between various actors and activities in the research field [3]. The European Commission’s Directorate General for Research and Innovation (DG RTD) felt the need to adopt a new term to describe an innovative and inclusive approach to conduct research and innovation (R&I) that aligned R&I outcomes to the values, needs and expectations of European society [4]. This terminology quickly took hold, especially in the research community. By 2014, there were already several workshops and conferences dealing with RRI around Europe, and RRI was discussed in the daily news and FP-funded RRI projects were making themselves and the concept visible. By 2015, RRI was also spread beyond Europe and it moved from workshops and conferences to actions [5].

In the last decade, the wide dissemination of the RRI approach was mainly due to the increasing criticality of the European—but also global—situation. The many societal challenges—such as economic crises, climate change, ageing population, food, water, materials and energy safety, public health, and security [6,7]—have caused a loss of trust in business, government, media, science and innovation [8]. In this context, RRI increasingly emerged as a possible way to pull Europe out of the crisis—a more effective solution to ensure smart, sustainable and inclusive growth [9], a chance to restore the public confidence in science and innovation [10] and a novel way for policy-makers to argue the case for responsible innovation [11].

However, the practical implementation of RRI is problematic, due to the complexity of the concept itself [12]. This complexity is illustrated by the lack of a single and directly applicable definition of the concept. Researchers, policy-makers and funding agencies within the European Commission (EC) have tried to define RRI to ensure its application; nevertheless, most of the actors involved in research and innovation are not fully aware of what RRI specifically refers to [3]. In 2011, Hilary Sutcliff, in a report prepared for the DG RTD, summarized the characteristics of RRI by defining it as a process which attempts to achieve a social or environmental benefit, to involve the public from the beginning, to assess the impacts on society and to anticipate and manage problems and opportunities, all in full transparency and openness [13]. The same year, Von Schomberg from the DG RTD defined RRI as “a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view on the ethical acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products” [14]. Finally, the definition of RRI given by the EC in 2012 emphasized ethics as a key aspect of the process—ethics is seen as a kind of instrument to “ensure increased societal relevance and acceptability of research and innovation outcomes” [15]. However, not only ethical issues are addressed. In 2013, RRI was described by the EC as a “comprehensive approach of proceeding in R&I” which will result in “research, products and services” [7]. In fact, the EC claimed that a RRI framework comprised other fundamental dimensions, or key principles, with six in total: ethics, gender equality, public engagement, science education, open access and governance [16]. With such features, RRI became a cross-cutting issue in the Horizon 2020 Framework Program [15].

Alongside the ‘institutional’ definitions of RRI, academics have also contributed as well to RRI definitions, most of whom (i.e., Stilgoe et al. [10], Stahl [17], Spruit et al. [18]) agree in defining RRI as a process including all actors by trying to anticipate, reflect and respond to the needs and values of society [3].

While the RRI concept is well known in the EU policy arena, many companies are not familiar with it, and are unaware of the scientific and governance discourse that has developed around it [19]. As pointed out by Martinuzzi et al. [20], RRI regards concepts and theoretical approaches previously used in science and technology studies, ethics and philosophy of technology, as well as ethical, legal and social aspects of research. However, companies have already undertaken activities in line with RRI, albeit using different terms (e.g., sustainable innovation, participatory design, open innovation, stakeholder dialogues, scenario development, circular economy, risk assessment). RRI is also congruent with what has become known as corporate social responsibility (CSR), which is a more established concept in business and industry [19]. Framing RRI in industry offers the potential to bring CSR from the margins into core strategic decision processes, achieving a stronger integration of the creation of social value in addition to economic returns. However, it may also spawn new conflicts [20]. According to Lubberink et al. [21], the problem with the current concept of RRI is that it is developed by researchers and policy-makers who are focused primarily on the conduct of responsible science and technological development without differentiating between research, development and commercialization, posing important challenges for the implementation of responsible innovation in the business context.

For the purpose of this article, RRI can be explained as an inclusive approach to R&I which aims to align the processes and outcomes of R&I with the values, needs and expectation of society by involving all actors in the process. Indeed, it shall be noted that RRI-based strategies and practices have shown to be capable of making R&I accessible to all the relevant actors and improve the partnership between science and society [4]. RRI can therefore be considered an ambitious challenge to create R&I policies driven by the demands of the general public and built on the engagement of all societal actors during the whole process [15]. In this sense, as claimed by the SwafS-14-2018-2019 call of H2020 Program [4], “territories have a specific advantage to address the complexity of the challenge set by the interplay between science and society.” RRI processes have direct implications on regional development and can be targeted to solve major social and regional problems. Since the local actors have an intimate knowledge of their own territories, their engagement in the co-creation of such development policies ensures the effectiveness and sustainability of the actions and strategies planned.

Additional knowledge on RRI can be found in some of the tools (e.g., MoRRI indicators; RRI toolkit; co-RRI platform) developed by EU projects dealing with RRI dissemination into R&I ecosystems or with the mapping of RRI impacts. However, neither of them has explicitly focused on the territorial potential of RRI, nor on the mapping of both the strategic and structural tools that territories adopt to shape their transformations, such as the regional development policies and the spatial and urban planning instruments.

Consciously or not, some territories, intended as geographical areas sharing common features, have already adopted local and regional development policies, through e.g., spatial planning instruments and activities, which are RRI-related, generating effects especially on the spatial dimension.

The aim of this study is to understand precisely how the RRI dimensions have been integrated into existing territorial and regional development policies, in order to increase the knowledge and awareness of RRI and to provide a basic support framework for territories. This framework will enable territories to acknowledge what they have done so far as well as to learn how to integrate the RRI approach in their commitments and planning.

This paper provides a comprehensive methodology to map the current inclusion of the RRI thematic elements (i.e., governance, public engagement, science education, gender equality, open access and ethics) plus sustainability into regional development policies and planning tools. The methodology has been developed within the H2020 SeeRRI project, which aims at developing a framework for integrating the RRI approach into regional development policies towards the establishment of a foundation for building self-sustaining R&I ecosystems in Europe. According to the SeeRRI project, a self-sustaining R&I ecosystem is considered to be complex, self-organizing and flexible to niche development, as defined by [22]; to provide access to global business ecosystems based on the local/regional innovation ecosystem; to be open to innovation, co-creation, users; to be trial-based, experimental, and to apply rapid prototyping methods in the real world.

To illustrate the mapping methodology, three territories are used as pilot cases for its implementation. The resulting RRI state-of-the-art pictures provide a baseline for the territories to understand which of their existing policies are sustainable, open, inclusive, anticipative and responsive and where, instead, it is necessary to increase the integration of the RRI approach in order to become self-sustaining RRI ecosystems. The paper also makes recommendations on further integration of RRI in territorial development policies and spatial planning tools based on the lessons learnt from the three pilot cases.

The paper is organized into five sections. Following this introduction, Section 2. Materials and Methods describes the mapping methodology, including the methodological background, the introduction of the data of interest and data providers, the data collection process and the representation of results. Section 3 presents the results obtained by implementing the methodology in the three pilot territories. Section 4 includes the discussion on the mapping results, including also the authors’ inputs for each territory to evaluate and then improve their current situation. This section also includes recommendations for RRI inclusion in spatial planning instruments. Section 5 presents the conclusions of this paper, the acknowledgment of main limitations and new threads for future applications and discussions.

2. Materials and Methods

The mapping of the current inclusion of RRI into regional development policies and planning instruments represents one of the first steps to building the state-of-the-art picture for the specific territory, in order to provide specific information on which dimensions have been most developed or which can be further integrated. To achieve this objective, a common mapping methodology has been established and then validated in three pilot territories. A methodological approach based on the breakdown of RRI into its thematic dimensions has been designed to map the inclusion of each element into regional policies and place-based activities.

According to the MoRRI indicators [5] and to the definition given by the EC [16], the six elements of RRI that are embedded into the methodology are:

- 1.

- Governance (GOV) is about making arrangements that lead to acceptable and desirable futures; measures that need to be robust, adaptable, responsible, shared and accountable. This dimension develops harmonious governance models for RRI that also integrate all the other dimensions.

- 2.

- Public Engagement (PE) is about co-creating the future by bringing together the widest possible diversity of actors on matters of science and technology in order to align the outcomes to the values, needs and expectations of society. The multi-actors exchange fosters more societally relevant, desirable, and creative R&I actions and policies, leading to a wider acceptability of science and technology outcomes.

- 3.

- Gender Equality (GE) means that all actors, women and men, are involved equally. There is still an under-representation of women in R&I. This element promotes gender-balanced teams, ensuring gender balance in decision-making bodies, and considering always the gender dimension in R&I to improve the quality and social relevance of the results.

- 4.

- Science Literacy and Science Education (SLSE) enables a sustained dialogue on R&I processes. Science education is essential to making this happen. This element enhances the current education process to better equip citizens with the necessary knowledge and skills to participate in R&I debates, and to increase the number of researchers by promoting scientific vocations.

- 5.

- Open Access (OA) addresses issues of accessibility to and ownership of scientific information and it can be moved into Open Science. It is widely agreed that making research results more accessible contributes to improving R&I—free and earlier access to scientific work might improve the quality of scientific research and facilitate fast innovation, constructive collaborations among peers, and productive dialogue with civil society.

- 6.

- Ethics (E) focuses on research integrity and on ethical acceptability of scientific and technological developments. European society is based on shared values. In order to adequately respond to societal challenges, R&I must respect fundamental rights and the highest ethical standards. Ethics should not be perceived as a constraint to research and innovation, but rather as a way of ensuring high quality results.

Moreover, acknowledging that the sustainable development is a shared goal that should underpin all of the human activities—from the business sector, to accelerate the companies which businesses transition to create a sustainable world [23], to urban and spatial planning, in accordance with SGD11 [24], the authors have decided to add an additional dimension to the 6 elements of RRI described above:

- 7.

- Sustainability (SUS). RRI is closely linked to the concept of sustainability. All countries are encouraged to adopt the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 drafted by United Nations in 2015 [24]. The Agenda has set 17 Goals for Sustainable Development (SDGs) for promoting prosperity while protecting the planet. Most of these goals are in line with the RRI principles, addressing the challenges for the society regarding sustainable development and growth. Some regions have adopted the UN Agenda to tackle their local issues.

Although sustainable development is not a central anchor for RRI, as shown in the work of Lubberink et al. [21], at the same time, sustainability is not a foreign concept to RRI, representing an overall aspect of RRI and a core principle of all current policies and projects. Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) has only lately included environmental sustainability as a key area for the social desirability of research and innovation, and for stakeholder dialogue in the RRI agenda [25,26]. This later addition of sustainability as a key area of RRI in the European program has led to an underrepresentation of sustainability (i.e., especially environmental sustainability) in the objectives of RRI [25].

Since RRI recognizes the responsibility of researchers in providing socially desirable, ethically acceptable and sustainable outcomes, the paper has included sustainability within the 7 dimensions of RRI to be considered within this research, together with governance, public engagement, open access, gender, ethics, and science education.

2.1. Data of Interest and Its Providers

The core of the mapping exercise is represented by the identification of existing references to the 7 dimensions (GOV, PE, GE, SLSE, OA, E, SUS) within the territorial policy instruments. However, to build a comprehensive picture of the RRI state-of-the-art of an R&I ecosystem, it was first necessary to fully understand the territorial characteristics. In fact, the mapping of RRI inclusion within territorial development policies comprised not only the targeted mapping for each of the dimensions, but also an overall framework of the territory. Moreover, in the SeeRRI project, each territory has identified a thematic focus. The thematic focus is a specific topic that the territories have identified as strategic, and that they decided to further investigate and develop during the entire project and beyond. A specific mapping in relation to the main focus produces more effective results in terms of laying the foundations for future commitments and improvements. For this reason, the mapping of RRI inclusion into the framework of the thematic focus is part of the general methodology.

B30 Area (ES), Lower Austria region (AT) and Nordland region (NO) are the three territories that are partner of the SeeRRI project and that have been identified as case studies. Each territory has been considered as an R&I ecosystem, relaying on already established networks of research and innovation actors. The partners from the three pilot territories are representatives of all quadruple-helix actors: government (regional authorities), business (economic cluster and SMEs), academic (research institutes and universities), and civil societal organization (confederation of enterprises). The territorial actors involved in the project represent both the public authority sphere and the other stakeholders’ sphere.

B30 is a strategic location composed of 23 municipalities in the Catalonia region in Spain, whose name came from the B30 highway, which is one of the most important traffic hubs in all of Catalonia, passing through numerous towns that surround Barcelona and encompassing half of the Catalan industrial network. The area is covered by Catalonia’s S3 Strategy and equipped with R&I infrastructures; for the aim of the SeeRRI project, the actors involved decided to focus on “zero waste” strategy.

Lower Austria is the largest province in Austria and nowadays is an important business location and focus of economic growth. The core of Lower Austrian RIS3 is the specialization in technologies and economic areas into technopoles and clusters. S3 is promoted through clusters, thanks to the Business Agency of Lower Austria, whose focus topic is Additive Manufacturing.

Nordland is a county in the Northern Norway region in Norway characterized by a strong presence of industries and clusters, as well as experience-based tourism. Nordland county has implemented a Smart Specialization Strategy since 2014 and now, they want to lift S3 to a more strategic level in the region. The detected thematic focus for the ecosystem concerns finding new ways to develop a more sustainable society through regional strategies and planning processes, as well as to involve different types of stakeholders.

A summary of the three steps which constitute the mapping is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The three sections in mapping RRI (Responsible Research and Innovation) inclusion within territorial development policies.

The detailed contents feeding the mapping are then deeply investigated, in order to build a comprehensive framework in which all the potentially relevant information can be collected and processed. The data of interest for the mapping are connected to the presumed data holders within the territorial actors; this identification of the data providers also facilitates the data gathering process. In the case of R&I ecosystems, the data providers can be grouped into two main categories:

- Public Authorities (PA): This is the institutional level that includes the whole ecosystem. It will depend on the territorial extent of the R&I ecosystem and on the governmental structure of the territory. It can be the regional authority, or an association of municipalities, a province or even a national authority. In general, it refers to the lowest institutional level that includes the whole territorial ecosystem. In order to be as flexible as possible, each R&I ecosystem can consider as PA whichever level of institutional government they believe is able to provide relevant documents and information, even more than one.

- Other Stakeholders (OS): This level refers mostly to cluster organizations based on the R&I ecosystem and quadruple-helix actors other than the PA.

Both representatives of the PA and OS hold data regarding general information (a), thematic focus (b) and the 7 dimensions (c). For what concerns the general information (a), data concerning geography, society, economy and local actors are asked of the PA while some information about the internal organization of clusters are asked of the OS. The information required about the thematic focus (b) is asked mainly of the OS representatives and consists of territorial data regarding the thematic focus (e.g., data on businesses and researches involved or on funds and infrastructures available in the thematic field) and of a collection of the main policy instruments and initiatives strictly linked to the thematic focus, that are systematized according to the 7 dimensions by cataloguing them under one (or more) main dimension/s. Lastly, the targeted mapping by dimensions (c) concerns all the policy instruments and initiatives of the PA as well as of OS that are strictly connected with the 7 dimensions. More specifically, those data are then classified with reference to one main dimension primarily addressed by the considered plan or action, which is also representing its core objective (i.e., a spatial planning tool is adopted to govern the territorial development of the considered area, therefore it has GOV as main dimension). According to the expected data provider, the contents required are listed in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Mapping dimensions (c) classified by data provider (i.e., Public Authorities—PA; Other Stakeholders—OS) and the main dimension (i.e., Governance—GOV; Public Engagement—PE; Gender Equality—GE; Science Literacy and Science Education—SLSE; Open Access—OA; Ethics—E; Sustainability—SUS).

Investigating the policy instruments through the lenses of the 7 dimensions contributes to establish whether a territory is committed or not into a specific dimension. To build a more comprehensive understanding of the current situation, along with the presence of the elements as described in Table 2 and the count of the initiatives, a more detailed description of them has been asked of the data providers (e.g., amount, type, keywords, objectives, main actions, people reached, the presence of the monitoring system). Moreover, a self-assessment of each initiative has been introduced as well, in order to understand if the absolute number or amount provided could be considered good enough or not for the territory in relation to their possibilities, resources and expectations. The self-assessment consists in answering the question “How would you rate it?” on a five-point Likert scale: very good, good, fair, poor and very poor.

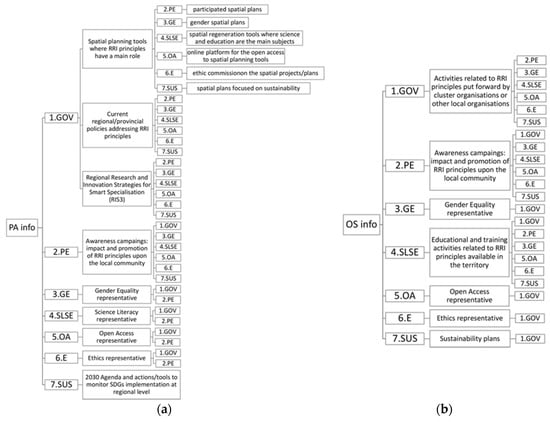

The contents of Table 2 are related to one main dimension, but further delineations of the topic are needed. Therefore, sub-categories have been introduced. The structure of the required data of interest, and in particular the relationships with the 7 dimensions and sub-dimensions, are made explicit in the two diagrams in Figure 1. This data framework has been designed to be as comprehensive as possible, although not all the topics and sub-topics are applicable to every R&I ecosystem. In addition, and for completion, the data gathering forms used for the RRI mapping campaign are included in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Structure of the linkages between contents and dimensions for (a) the PA’s data of interest and (b) the OS’s data of interest.

Spatial planning tools where RRI principles have a main role are all the regional or urban planning policies, regulations or actions addressing one of the dimensions as their main goal. These include participated spatial plans showing the PA’s intention to engage the citizens; gender spatial plans showing how the PA aims to balance the gender gap by customizing the urban environment; spatial and sectorial plans where science or literature are the main focus with the intent of increase the Scientific Education; and an Online Platform for spatial planning tools ensuring the open access.

Regional policies addressing RRI principles are economic policies, labor market policies and others with one of the other dimensions as a main topic. Such policies refer to the territory as a whole (in some cases, even to an even larger area than the R&I ecosystem) but they are not necessarily spatial planning tools. They have been chosen for the present mapping since they are believed to complement the overview on regional and planning policy instruments, but from a thematic perspective.

Specifically, at the regional government level, the R&I ecosystems have been asked to go into details of their RIS3—Regional R&I Strategy for Smart Specialization. RIS3 are place-based policy instruments promoted by the EU cohesion policy [27], able to build competitive advantage based on regional strengths and potential [28]. The RIS3 documents are analyzed by looking at their priorities and pillars, the connected actions and instruments, and the monitoring and evaluation system (if existing), always referring to one dimension in turn.

Following Smith [29], who claims the integration of participation and behavior—rather than a distinction—while studying behavior, social marketing and the environment—participatory planning has been investigated, searching for the presence, number and main objectives of awareness/social marketing campaigns on RRI principles which provide the basic knowledge on the promotion of RRI in the local communities. Lefebvre [30] conceptualizes society as a marketing system, where a number of strategies such as communication, regulation, finance and community mobilization can be applied. It could be argued that this approach conceptualizes social marketing as integral to the policy process, rather than a mechanism for behavioral change brought in at the end [31].

For some of the dimensions (GE, SLSE, OA, E), where it is hard to find specific tools, plans or policies, an effective way to map their inclusion into the administrative set-up of the territorial PA has been to check the presence of an institutional representative (that could be one person or even an entire dedicated office) or of organizations promoting these principles as a core mission.

Some governments, especially regional ones, may have adopted (but it is not mandatory in all countries) a targeted 2030 Agenda and actions or tools to monitor SDGs implementation. Identifying the main challenges and objectives for the region linked to each SDG helps to map the implementation of sustainability into the territory.

The presence of activities related to RRI principles, such as EU projects or non-EU projects carried out by local organizations in the area and focused on PE, GE, SLSE, OA, E or SUS as their sub-dimension, can help understand the OS commitment in relation to RRI.

The implementation of awareness/social marketing campaigns, put forward by the clusters organizations or other local-based organizations (OS), provides information on the current promotion of the RRI principles in the local communities, although the data available could not make possible a distinction among awareness campaign and social marketing ones.

The presence of an institutional representative for GE, OA and E within the administrations of the cluster organizations and other relevant organizations (OS) contributes to the implementation of RRI principles within the territory.

Educational and training activities focused on one dimension, i.e., projects, programs or scholarships available in the territory for courses or graduate programs, make the RRI concept visible and increase the sensitivity to the theme.

The presence, and related contents, of eventual Sustainability Plans put forward by the cluster organizations and other relevant organizations based in the territory (OS) highlights the emphasis on sustainability within the territory.

2.2. Data Collection Process

The data gathering campaign in the three pilot territories was conducted using a data collection sheet filled in by the representatives of the PA and the OS by accessing existing databases. No further surveys or questionnaires to third parties were anticipated. In fact, the identified territorial actors have been placed in the condition to gather most of the information required from their existing databases or through a process of re-elaboration of the available information.

The form consists of 5 sheets: (i) instructions on how to fill in the data collection form; (ii) general information about the features of the territory and its economic and business clusters; (iii) thematic focus information; (iv) PA data regarding the RRI-related policies and planning instruments of the institutional level; (v) OS data regarding RRI-related activities of the clusters and all the other relevant stakeholders involved. For each of the three territories, the sheets (ii), (iii), (iv) and (v) were filled out jointly by the representatives of the PA and of the OS among the territorial partners of the SeeRRI project.

The four stages of the data collection process were:

- Distribution of the data collection form to the PA and OS representatives of each territory for a joined compilation of the form using existing databases and basing on their own knowledge;

- Bilateral remote meetings between the authors and the territorial actors involved in the campaign to clarify the potential doubts and concerns;

- Exchange of several draft versions of the data gathering form to further improve the information collected and produce as comprehensive of a picture of each territory as possible;

- Final check of the data collected by the authors for the following analysis.

3. Results

The data collected from the three case studies through the data gathering sheet constitute the experimental results of the mapping, demonstrating the applicability of the methodology developed to real contexts in Europe. Once the three forms were collected, the data were analyzed and classified. An interactive visualization of the results of the mapping campaign was created using Prezi software to elaborate the narrative of the three territories. This visualization reports the current commitment of the three SeeRRI ecosystems with RRI, visualizing whether concrete actions were put into practice by the local actors and to what extent, as well as providing links to websites and further references.

The main results are described for each of the three territories in the following Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3. The complete overview of the data available can be found within the Prezi presentation of the SeeRRI territories [32] and in the SeeRRI project, Deliverable 2.3—RRI within Regional Development Policies: The Case of Catalonia, Lower Austria and Nordland [33].

3.1. B30 Area Results

The B30 Area is located in Catalonia (ES). Although it has an extension of only 485 km², it boasts 38,000,000 euro GDP and a high-density population of 1,036,000 inhabitants. The Government of Catalonia (GENCAT) and the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) have been the territorial actors involved in the mapping of B30. From the data provided, the area has been found to be very vital and productive, with a quadruple-helix of stakeholders (12 academic institutions, 30,173 industries and business companies, and plenty of civil society organizations) involved in six cluster organizations committed to sustainability, innovation and efficiency.

The thematic focus has been identified by the B30 responders by using the following keywords: zero waste, recycling, circular economy, sustainability, industrial symbiosis. The scope of the thematic focus affects many companies in important industries in B30, such as packaging and food. A wide group of researchers are currently dealing with the zero-waste objective—the research staff counts 160 people so far and it has been considered already a good number by the B30 partners according to the self-assessment. Some of the infrastructures available in B30 region are directly related in the thematic focus: UAB Open Labs, Parc de Recerca coworking spaces and Esade creapolis. The current infrastructures and tools operating in the thematic focus have been evaluated as good by the B30 partners through the self-assessment section of the data gathering form.

In the B30 area, there have already been implemented initiatives since 2017 that can be counted as strictly linked to the thematic focus, demonstrating the commitment of the actors based in the area to the achievement of the shared objective of zero waste. The supra-municipal initiative Valles Circular (2017-2019) [34], promoted by the Consell Comarcal Vallés Occidental, aims at boosting circular economy at local level focusing on management and governance. The initiative seeks also the participation of all the actors of the quadruple-helix on circular economy, supporting the economic, environmental and social sustainability. The Green Digital Vallès [34] is an education program started in 2017 to promote the employment of young people in the context of digital and sustainable industrial transformation. It is a county initiative promoted by the Consell Comarcal Vallés Occidental to foster science education on sustainability and digital issues. According to the respondents, data analysis on the municipal waste management performed in 2017, and on the municipal agricultural system towards sustainability performed in 2018 in the metropolitan area of Barcelona, also contributed to support the implementation of zero waste and of the sustainability issue. Moreover, strategic analysis to understand the conceptual approach to zero waste policies at regional level [35] were also introduced in 2019 by GENCAT to cover the governance sphere of the thematic focus. The sustainability sphere resulted to be the most affected one by the actions already put into practice on the thematic focus chosen by B30, and this is mostly because sustainability is a cross-cutting issue of the thematic focus itself; however, also governance, public engagement and science education are among the affected dimensions.

The governance, public engagement and sustainability dimensions have been directly enforced by the Reflexió Estratègica Metropolitana (REM) [36], a strategic metropolitan spatial plan that has been developed, thanks to public participation, and that which contains social inclusion as one of its main actions. The open access to spatial planning documents is provided by the metropolitan area online platform [37]. In addition to this, a number of provincial policies are addressing RRI principles as their main objectives: gender equality, science education, open access and ethics. The Regional Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization of the Catalonia Region (RIS3CAT) [38] has defined priorities in line with RRI governance, pubic engagement, open access and sustainability. RIS3CAT foresees participation and quadruple-helix collaboration among its priorities, to be put in place by instrument as RIS3CAT Communities or Projects of Territorial Specialization and Competitivity. Not only did the public sphere take care of the RRI governance, but also cluster organizations and other local organizations, especially through the implementation of 28 EU and 25 non-EU projects focused on all the RRI main dimensions and on sustainability, as well as through the establishment of institutional representatives for addressing gender equality, open access and ethics. Moreover, eight training programs and projects focused on RRI governance have been reported in the B30 area.

Public engagement has been widely implemented in practices and initiatives such as REM [36] and RIS3CAT [38] presented above, but also citizens resulted to be involved in organizations that promote RRI principles as a core mission, such as gender equality, science education, open access and ethics. Only one EU project on public engagement has been reported by the cluster organizations and this result has been self-evaluated by the respondents as poor. Eleven training programs/projects focused on public engagement have been self-evaluated as good.

Gender equality has been reported with not enough spread inside the public sphere. However, it resulted to be the main objective for two socio-economic policies that were put into practice by the public authorities. As socio-economic policies, they fall into the governance sphere of RRI, but still are related to equality, gender-based violence and education. At OS level, the gender equality dimension has already received quite a bit of attention, not only thanks to the presence of institutional gender equality representatives, but also thanks to its implementation through three EU projects (i.e., EGERA, MISEAL, GIMMS), and two non-EU projects focused on gender equality; gender equality awareness/social marketing campaigns put forward by cluster organizations or other local organizations based in the area in the past five years; and eight training programs/projects.

Several educational and training activities related to RRI principles have been implemented in the area: 8 focused on RRI governance, 11 on public engagement, 8 on gender equality, 4 on open access, 5 on ethics, and 6 on sustainability. At the PA level, one education policy focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and science education has been implemented; while, according to the self-assessment, a good number of projects were put forward at the OS level, 14 EU projects and 23 non-EU projects focused on science education. Indeed, science education has resulted to be one of the main themes for 22 awareness/social marketing campaigns at the PA level and OS level.

Open access has been promoted as a core mission by at least one organization at public level and it is recognized as the main objective of an institutional representative at the cluster organizations based in the area. In this framework, the metropolitan area of Barcelona is provided with an online platform [37] which ensures the open access to spatial planning documents; two socio-economics policies have transparency as the main objective; the RIS3CAT [38] has open innovation and social innovation among its priorities, to be put in place by instruments as the Digital Agenda; and one EU project and four training programs focused on open access were put forward by the OS level.

The embedment of the ethics dimension has been reported by the PA through the presence of one organization promoting ethics as a core mission; and by the OS with the presence of an institutional ethics representative at the cluster organization based in the area. The pursuit of ethical standards or objectives is not explicit in other RRI principles-related instruments, but it can be clearly found in the Code of ethic and good governance [39] developed by the Consell Comarcal del Vallès Occidental in 2019, that includes quality citizen participation and transparency as its main objectives; and in one EU project and five training programs focused on ethics implemented by the cluster organizations or other local organizations.

Moving to the sustainability dimension, the Catalonia Region has identified a series of challenges and objectives to meet the UN Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 through The 2030 Agenda: Transform Catalonia, Improve The World [40]. In particular, they focus on resources management, sustainability, eco-innovation, waste management, employment, inclusion, poverty, society wellbeing, open innovation and social innovation; through these objectives, B30 as part of the region, aims to directly face all the SDGs, excluding the 4th, 14th and 15th SDGs only. Although the PA is committed to a regional Sustainability Agenda [40], sustainability remains mainly a cross-cutting theme in several public plans or programs, such as in the REM strategic plan [36] or in the RIS3CAT [38], and in the current activities of the OS level, through six training programs and eight EU projects focused on sustainability.

3.2. Lower Austria Results

Lower Austria, with a land area of 19,186 km² and a population of 1,612,000 people, is the largest state of Austria. It is a leading economic performer among the regions of Europe. It has a GDP of 57,349,000 euro and hosts 18 academic institutions, 102,000 industries and business companies and more than 100,000 civil society organizations. It is a vibrant area from many points of view and the clusters have a main role in the regional economy, involving the quadruple-helix of stakeholders in sustainability, resource efficiency, technology, quality and safety. The Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT) and the Business Agency of Lower Austria (Ecoplus) have been the territorial actors involved in the mapping of the Lower Austria ecosystem.

At the time when the data were collected, the respondents from Lower Austria identified in additive manufacturing (AM) and 3D printing (AM for metals, polymers, ceramics), the keywords for its thematic focus. This focus influences the manufacturing sector and aims to reduce the costs of production by leveraging the opportunities provided by the technology to facilitate mass customization of industrial products. The specific objective is to build up an ecosystem from education, R&D, companies, equipment producers, quality requirements and product development. Forty-two companies and associations have been already involved in the thematic focus, a commitment that has been evaluated as fair according to the self-assessment of respondents, as well as for the 25 people in the research staff, while the amount of more than 100 people in the business staff has been self-evaluated as very good. In addition, the respondents reported and self-assessed as fair, the fifteen jobs created in the thematic field and safeguarded by the clusters.

Some of the infrastructures available in Lower Austria region have a direct connection to the thematic focus. Two incubation and coworking spaces (i.e., Technology Center Wr. Neustadt, Zukunftsakademie Mostviertel) have been, however, self-evaluated as poor; eight scientific-technical services as good; and three access to contacts and networks (i.e., House of Digitalization; Mechatronics Cluster; Technopol Wr. Neustadt) as fair.

The provincial government of Lower Austria has developed policies, plans and other instruments to govern the implementation of RR principles, in particular, public engagement and science education, but also gender equality, open access and sustainability. The Regional Strategies 2024 can be considered as strategic spatial planning tools where public engagement has a central role in the whole process, from the preparation to the implementation. It must be noted that Lower Austria has five main regions and each of them have developed their own regional strategy 2024 [41,42,43,44,45]. The Regional Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization of Lower Austria [46] has defined priorities explicitly in line with pubic engagement and science education. In the region, there are institutional representative for some of the RRI dimensions, in particular, for gender equality (i.e., both at the PA and OS levels) and for ethics (i.e., in medicine and health). However, the RRI principles embedded into governance instruments and tools have not always been explicit enough to allow the detection of RRI into such initiatives, often implying a negative self-assessment from the respondents.

Public engagement has been reported to be mainly achieved thanks to awareness/social marketing campaigns addressing the local communities promoted by the OS level. The RRI principles involved in such campaigns have been gender equality, science education, open access and sustainability, although the self-assessment for each of these dimensions varies from good for gender equality, to very poor for open access. The concept of public engagement was widely implemented at the PA level in other practices. Indeed, public engagement is the only dimension among the seven studied that has been explicitly considered in spatial planning tools and regional policies, and RIS3 of Lower Austria by the provincial government of Lower Austria: Hauptregionsstrategien 2024 [41,42,43,44,45] collects the main regional strategies for 2024 [29,30,31,32,33] and involves municipalities, civil society organizations, politicians, regional government departments and spatial planning experts. According to the self-assessment, it has been rated as good; e5 Country Program for Energy Efficient Communities [47] is one among the initiatives that promote public participation (e.g., in the field of energy; in the field of ecology; to improve the attractiveness of the region); and the RIS3 of Lower Austria [46] identified cooperation as one of its priorities to be implemented through the Cluster Program. The implementation of cooperation and participation is monitored through participation quotes in initiatives to increase the competences, cooperation through the clusters and collaborative projects, and specific events organized in the technopoles.

At the provincial government of Lower Austria (PA level) is established the Women’s Department, an office that focuses on gender budgeting, parent-oriented personnel policy which makes career conformable with parenthood, and spatial development for women and men. On the other hand, Ecoplus (OS level) is provided as well with an institutional gender equality representative. Gender equality is also a concept at the basis of other RRI-related instruments implemented by both the provincial government and the clusters’ business agency: equal opportunities in Lower Austria are the objectives of policies and projects put forward by the provincial government, such as Gender Mainstreaming and GenderStrat4Equality [48,49,50]; awareness/social marketing campaigns on gender equality put forward by Ecoplus and the cluster organizations have been self-evaluated as fair and able to reach a good number of people.

Science education has been already embedded by Lower Austria as an objective in provincial policies (e.g., see the Science Academy Niederösterreich [51]); however, according to the self-assessment, the results are not yet satisfying. On the one side, at the PA level, it has been also possible to recognize science education as an objective for the RIS3, considering that consulting for innovation beginners is one of the priorities to be implemented [46]; on the other side, Ecoplus has implemented science literacy through the promotion of four awareness/social marketing campaigns in the past five years. According to the estimation provided by the respondents, 100,000 people were reached by such campaigns, an achievement that has been self-evaluated as fair.

Open access and ethics are the most under-developed dimensions represented in the data gathered. Very few initiatives have been mapped under the open access dimension (i.e., three promoted awareness/social marketing campaigns in the last five years implemented by Ecoplus and the presence of an online portal such as the Transparence portal) [52]. Ethics is almost absent, with the exception of the field of health and medicine through the presence of ethics commissions.

Focusing on the sustainability dimension, results show that both PA and OS are committed in sustainability-related activities, starting from the adoption of a national Sustainability Agenda [53]. However, the mapping exercise was probably not able to highlight them all, leading to a limited level of satisfaction according to the self-assessment. The Lower Austria region has identified a series of challenges and objectives to meet the UN Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. In particular, they focus on employment, inclusion, poverty, resources management, social wellbeing, innovation, and e-government; through these objectives Lower Austria aims to directly face all the SDGs with the exclusion of the 4th, 14th, 15th and 16th SDGs. At the OS level, among the activities aimed at fostering sustainability, there are initiatives awarding sustainable projects. In addition, sustainability has also been reported as a central theme for most of the existing territorial development policies already linked to a specific RRI dimension: the Lower Austria Climate and energy program 2020 [54] is mainly focused on environmental sustainability and provides actions on buildings, mobility, and circular economy; five awareness/social marketing campaigns on sustainability were promoted by Ecoplus in the past five years, and this result has been assessed as fair, although the number of people reached has not been provided.

3.3. Nordland Results

The Nordland region is part of Northern Norway (NO) and it is the second largest area of Norway’s 11 regions with a very long coastline and an extension of 38,482 km². It counts a GDP of 10,825,000 euro and a medium-low density population of 243,335 inhabitants distributed in 44 municipalities. The economy of Nordland is strongly globalized and it boasts a long tradition of cooperation with regions, knowledge institutions, and businesses, also in other parts of Europe; the region also includes 10 academic institutions, 29,541 industries and business companies and 7613 civil society organizations based within the area. Nordland’s innovation strategy is on the European Union’s smart specialization platform and it has innovation clusters in several industries including tourism and seafood. All the five territorial clusters identified involve actors from business, academia and civil society, stating that the collaboration between different types of actors is an affirmed practice in Nordland. Nordland Research Institute (NRI), Nordland County Council (NFK) and the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) are the territorial actors involved in the mapping of Nordland region, among the SeeRRI project partners. It is important to note that the respondents did not provide answers to the self-assessment questions, therefore the results in this territorial case lack this set of information.

At the time when the data were collected, the partners from Nordland identified in sustainability and stakeholder engagement, the keywords representing the thematic focus selected for the SeeRRI project. Sustainability issues affect many companies in important industries in the area, but also many academic researchers (i.e., at Nord University and NRI) are involved in research that addresses sustainability issues. Moreover, many subsidies are provided for sustainability-related innovation projects in the private sector. The region has three incubators (i.e., Kunnskapsparken Bodø, Kystinkubatoren, Kunnskapsparken Helgeland) and two industrial parks (i.e., Fabrikken Næringshage, Sentrum Næringshage) supported by public funds. The incubators and industrial parks facilitate access to contacts and networks.

Regional plans and strategies strictly linked to the thematic focus have been implemented since 2017, demonstrating the commitment of the actors based in the area to the achievement of a sustainable development of the region. The Strategy for tourism in Nordland 2017-2021 [55] is a regional strategy promoted by Nordland County Council where the sustainable use of resources is described as an important strategic issue. The Sustainable and innovative agriculture in Nordland [56] is a regional plan promoted by Nordland County Council including the sustainable use of resources as an important element of the plan. The Regional climate plan [57], promoted by Nordland County Council, focuses on reducing carbon emissions to promote a sustainable environment. According to the data provided by the respondents, a correspondence between existing initiatives linked with the thematic focus and the implementation of other dimensions rather than sustainability, has not been found.

Nordland has developed a number of policies, plans and other instruments to govern the implementation of RRI principles and the related processes. The public engagement dimension and that of sustainability have been directly enforced by the regional plan, Guidelines for area policy 2013-2025 [58], which includes guidelines for area policies where the environmental sphere of sustainability has a main role and the general work process is a co-development. The open access to spatial planning documents is provided by a county online platform [59]. Nordland has a Smart Specialization Strategy (i.e., Innovation strategy for Nordland 2014-2020) [60] that focuses on growth based on three strong innovation ecosystems: seafood, mineral production, and experience-based tourism. Moreover, the RIS3 has defined actions dealing with pubic engagement, science education and sustainability. The region has already implemented a number of instruments and tools (i.e., a strategic regional plan, more than seven policies addressing RRI principles, the RIS3 and other activities put forward by clusters) for the governance of RRI-related topics, confirming a strong commitment to the RRI embedment in their future development.

Public engagement has been mainly achieved thanks to awareness/social marketing campaigns upon the local communities promoted by both the PA sphere and that of the OS. Objectives related to science education, gender equality and sustainability have been at the basis of awareness/social marketing campaigns implemented by NCC. The dimension of public engagement has been implemented in other practices put forward for the development of the Nordland area: Public engagement is at the basis of the Guidelines for area policy 2013-2025 [58], a strategic regional plan co-developed involving stakeholders such as indigenous people and industry stakeholders; the Regional climate plan [57] has the competency in communication, reduction of climate gases, adaptation to climate change and pollution awareness between its main objectives and it is based on public engagement; and the Innovation strategy for Nordland 2014-2020 (Nordland RIS3) [60] also contributes to the promotion of public engagement.

The SeeRRI territorial partners of Nordland have referred to equality dimension rather than gender equality while completing the data gathering sheet, since they are believed to be a more representative topic for their region. In this framework, the public level represented by NCC boasts a representative working on issues specific to the indigenous people and also the implementation of other equality-related activities such as the Universal accessibility policy [61], which has equality and inclusiveness as its main objectives. The OS level has promoted initiatives with equality at center stage, focusing mainly on gender equality (e.g., the awareness campaign encouraging women’s participation in engineering). In addition to this, NHO also financed research on gender equality in management, supporting women’s education for leadership roles and positions.

At OS level, NHO is provided with an institutional science education/literacy representative. Several educational and training activities related to RRI principles have been reported in the area, mainly focusing on RRI governance, gender equality, ethics and sustainability. Moreover, the Norwegian universities and colleges, in collaboration with NCC, are required to establish a Council for cooperation with Working Life (RSA), which has been a way to strengthen the social and regional relevance of educational institutions. NCC has also supported an initiative for connecting high schools with industry in collaboration with Kunnskapsparken Helgeland. Science education is also a core mission of county policies at the PA level and of the Nordland RIS3 2014-2020. Through regional development funds, they have financed many efforts, i.e., Forskningsdagene, a national event localized to the different regions, and Lytring, a series of debates between academics where the public takes an active role.

Open access is promoted as a cross-cutting topic, but it has not been reported as a main theme for specific initiatives. The NCC is provided with an online platform which ensures the open access to spatial planning documents. Awareness/social marketing campaigns on open access have been reported as implemented by NHO.

The pursuit of ethical standards or objectives has not emerged explicitly in other RRI principles- related instruments, but it has been quite evident according to ethical guidelines for civil servants in Nordland with the main objective of promoting trust, openness, and loyalty; and the initiatives related to the active engagement of inclusiveness of migrants in the work-life and in helping youths, people with disabilities, people with addiction problems, and so on, back into the work life. The OS level has reported few activities related to ethics, but NHO actively encourages its members to take responsibility through the provision of educational materials and services to avoid ethical conflicts.

Moving to the sustainability dimension, the PA has identified a series of challenges and objectives to meet the UN Sustainable Development Agenda 2030. In particular, according to the Sustainability Agenda, [62] they focus on eldercare, exchange programs, ground water protection, wind energy, high-quality education, smart specialization, preservation of indigenous people’s culture, communication, awareness, adaptation, and coastal protection; through these objectives, Nordland aims to directly face the SDGs of nos. 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14. As already mentioned, sustainability is also a cross-cutting theme for most of the existing territorial development policies and it is also the core of the thematic issue identified by Nordland’s SeeRRI partners.

4. Discussion

The data collected have been elaborated according to the results of the monitoring of impacts of the relative policy or instrument (if available), the self-assessment of the territorial partners involved in the application of the RRI mapping methodology and further considerations deriving from the features of each specific context, as well as from the lessons learnt from other territories. Based on the data provided by the three SeeRRI territories, the authors have identified—for each of them—on the one side, the most developed RRI dimensions and, on the other side, the ones where there are still room for improvement.

In the B30 area, public engagement, science education and governance instruments addressing RRI principles are practices that are already well-developed within the territory. Gender equality and sustainability are under-represented issues while ethics and open access are still insufficiently included into regional development policies and urban planning instruments.

The results from Lower Austria mapping indicate that there is still room for improvements on ethics and open access, but also RRI governance and science education are dimensions that can be further included in the current policy instruments. On the other hand, public engagement, gender equality and sustainability are topics that are well-covered in current territorial development policies. Despite the absence of a self-assessment from the territorial actors of Nordland, the available data were discussed and elaborated by the authors. The resulting mapping reveals a good inclusion of sustainability, governance and public engagement into their current development policies. As in B30 and Lower Austria, ethics and open access seems to be the most under-developed RRI dimensions, while science education and gender equality are present, although their inclusion can be improved.

The general trend emerging from the three case studies considered reveals that the most critical dimensions of RRI to be included in territorial development policies and urban planning instruments are ethics and open access. In some contexts, it can be observed that the RRI dimension of ethics has been already included in labor directives and guidelines, as well as in the health and medicine field, but it could be expanded also to other fields. For instance, both the public authorities and cluster organizations could try to include specifically ethical standards in their development policies and instruments, also by developing targeted awareness/social marketing campaigns. Ethics, as a criterion for deciding on precise questions and options, may be a way of ensuring high quality results. Not only in the decision process but also in the previous stages, during the research and analysis, to build the knowledge framework to make the decisions, ethics guarantees the integrity of the research and the ethical acceptability. In fact, ethics may be seen as a standard for quality and social acceptance of research results, planning choices or strategic priorities and as a selecting criterion for some decisions and actions foreseen by plans and strategies. Moreover, the establishment of an ethics commission on spatial plans and other development planning instruments may be a good way to ensure that the ethical dimension is well-considered during the plan choices (e.g., location of infrastructures, allocation of services, territorial compensation, inhabitants’ balance).

As far as the three case studies show, open access is mainly seen as transparency and openness in public processes (i.e., to request information) and in publication of specific policies (i.e., through online portals or open platforms to access spatial planning documents or other public policies). In this sense, open access should be also included as a priority in territorial development campaigns and in the current RIS3. Transparency mostly applies to public authorities, which are often obliged by national or regional laws to publish in open access documents and procedures, and to make the general public aware of decisions on urban planning and territorial development. Not only should the open access to spatial plans or development policies be achieved, but also surveys, analysis and other documents that are used as a background for building the plans and development policies, in order to make available to the general public all the information necessary to understand the plan’s choices and in order to make up their own mind for the place where they live. On the other hand, open access is still a thorny question, especially in the private sector, mainly for intellectual property issues. However, evidences show that open access, seen as free and easier access to scientific works and research (open science) in academia, business and civil society, may also help the socio-economic development and the scientific growth [63]. This implies that all the stakeholders involved in a territory should try to guarantee a free and earlier access to scientific works in order to improve the quality of scientific research and facilitate fast innovation, constructive collaborations among peers, and productive dialogue with civil society. If open access is achieved as widely as possible, then the opportunities for conscious involvement and commitment of all stakeholders in the processes are greater. The more the results are accessible, the more they contribute to improve R&I.

For what concerns the other dimensions of RRI and the sustainability dimension, the analysis of the three territorial cases has pointed out which are the existing territorial development instruments that are more suitable to include, and which kind of activities and actions can be put forward by public authorities and clusters to increase the RRI embedment. The spatial and urban planning instruments should be able to govern RRI principles (i.e., public engagement, science education, gender equality, open access and sustainability) by incorporating them as contents or issues; but also the overall concept of RRI must be included in the whole planning process, resulting in planning instruments and processes that are diverse and inclusive, anticipative and reflective, open and transparent, and responsive and adaptive (RRI process dimensions).

Participatory processes during the drafting of spatial plans and development policies are already a common practice in many territories to pursue public engagement, as well as the promotion of awareness/social marketing campaigns on specific RRI dimensions, mainly gender equality and science education. Citizens and all the relevant actors should be involved during the whole process, from the elaboration to the approval and also during the implementation and monitoring of spatial plans and development policies, in order to guarantee the acceptability of the choices made and also to obtain more concrete results in the achievement of the planning objectives [64]. Moreover, the co-creation in the first phases ensures that different perspectives are included, aligning the outcomes to the values, needs and expectations of the whole society. Not only the behavior of citizens but also that of public administrators and entire organizations could be addressed by behavioral public policy [65].

Gender equality is an objective that many territories have set as a target for their development policies (i.e., in RIS3 or in socio-economics policies), or even as a main theme in training programs and projects. However, including gender equality in urban and spatial planning is still a new practice which has not been fully exploited yet, and it arises from the fact that the urban society is becoming more and more diversified, with divergent interests that often entail conflicts between different user groups. As the Manual for Gender Mainstreaming in Urban Planning and Urban Development [66] states, gender-sensitive planning is a differentiated planning culture. It considers the needs of target groups who are often overlooked, and the equitable distribution of space and time. Moreover, the reflection on the underlying values of urban planning from a gender-sensitive perspective supports a planning culture based on everyday needs.

Targeted development policies are already addressing science education as their main objective in many territories; moreover, training activities and learning programs on RRI principles (i.e., mainly on gender equality, public engagement and sustainability) are widespread practices. However, an accurate and targeted planning and design is often required in order to provide dedicated spaces and infrastructure for innovative science education (e.g., Science Parks, Scientific and Technical Pole, public university campuses, research centers), to also improve the quality of the educational and training spaces and the provision of technologies and infrastructures for the scientific research and education.

Finally, sustainability is commonly addressed by many different development instruments collected, starting from the spatial planning tools, which are the main instruments to achieve the 11th goal of the UN Sustainable Agenda, Sustainable cities and communities [23]. In fact, they can be tailored to many areas of interest (e.g., mobility, energy, public infrastructures, ecological network), always including the concept of sustainability in all its aspects, by developing i.e., Sustainable Mobility Plans, Climate Change Plans, Sustainable Energy Plans, etc. Of course, in the formulation and implementation of such plans, not only the 11th SDG should be tackled, but also as much of the SDGs as possible. Moreover, the strategic planning instruments should integrate the 17 SDGs, and a monitoring system to systematically report the implementation of all the promoted projects and initiatives related to sustainability should be enforced (i.e., Report on UN Sustainable Development Goals).

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5.1. Concluding Remarks

Describing the degree of inclusion of Responsible Research and Innovation in European territories is still a challenge. When it comes to aligning R&I outcomes to the values, needs and expectations of the society, the investigation of the characteristics of the regional development policies and urban planning instruments is believed to be a key opportunity to picture the state-of-the-art on how territories have been able to embed RRI into policy instruments driving the development of such territories.

This research has provided a concrete solution to the issue of understanding to what extent RRI dimensions (i.e., governance, public engagement, open access, gender, ethics, science education) and sustainability have been included so far into regional development policies and spatial planning instruments. The developed mapping methodology has been applied to three territorial pilot cases involving the partners of the SeeRRI project. The resulting RRI state-of-the-art pictures represent the foundations for the territories to improve the integration of the RRI concept in their commitments, in order to become self-sustaining RRI ecosystems. Recommendations have been provided for further integrating RRI in spatial and urban planning policies and tools.

The research has clearly shown that embedding Responsible Research and Innovation embedment into territorial development policies and spatial planning tools is not a clear and linear process. The methodology developed has been aimed not only at collecting information on the level of inclusion of RRI into current policy instruments, but also at providing suggestions to overcome the difficulties encountered during the mapping process, and to further embed RRI into the territories.

Through the implementation into three territorial case studies with an already solid network of R&I local actors, this methodology has proven itself to be a valuable technique to actually map the current inclusion of RRI principles into development policies and spatial planning instruments. The mappings obtained were, in fact, able to provide clear pictures of the current RRI state-of-the-art in the three territories—pictures that constitute the basic knowledge for future considerations and commitments.

5.2. Limitations

Some limitations should be acknowledged. First, the present mapping methodology has been built to be as comprehensive as possible, trying to cover all those practices, policies and tools developed by a given territory that may, in some way, have a connection with the RRI principles of gender equality, public engagement, open access, ethics, science education, governance and sustainability. The amount of necessary data is very high, therefore, the effort from territories strongly depends on the availability of the dataset and existing collaborations and partnerships among the various territorial partners. To perform the mapping exercise, each territory should rely on its own network, involving all the stakeholders able to find the requested data. Of course, this requires a great effort for the territories that has not achieved, so far, a good level of collaborations among the relevant stakeholders. However, it could also be seen as the chance to strengthen the territorial R&I network.

Despite the existence of a wide territorial network, the data required are not always available or accessible. The data may not be involved in the mapping process, the data may not be available in open access, or some data may not have a clear connection with RRI. In fact, it could be that the data available are too generic and it is not possible to detect if a specific dimension is included within them. In the latter case, it is important to note that the RRI principles may not be explicitly present but are still included in some way, and this methodology may not be able to detect the connection.

Finally, to be able to elaborate on the data collected in order to build an image of the current level of inclusion of RRI principles within territorial development policies and urban planning instruments, information on impacts and actual benefits brought by the implemented actions, plans and policies is necessary. Unfortunately, at the time when the mapping exercise has been performed, most of the policies and instruments implemented were not equipped with a monitoring system and/or set of indicators to assess the impacts and results. In absence of the monitoring, it has not been possible to perform a detailed assessment of the current planning situation and to evaluate the implementation of RRI-related plans and strategies. The mapping methodology developed during this research tries, in fact, to overcome the gaps left by the quite common absence of targeted monitoring of impacts and results through the integration of a self-assessment system performed by the territorial partners. The self-assessment results are, then, an important part of the methodology because they serve as the basis for subsequent discussions and considerations about the future directions and improvements of the specific territory. Most of the numbers and figures collected are not indicative of positive or negative impacts on the territory. Neither does the presence of plans, programs or other activities within the territory imply measurable impact. Different contexts, targets and stakeholders may affect the potential impacts and results of policies, plans and other instruments. However, not only the policy structure, the foreseen actions, the strategies and the challenges addressed by such instruments are able to be evaluable through simple processes and this is why an assessment coming from the local actors, who directly know the context and the actions made, is fundamental. Of course, it is not always easy to rate the actions and plans put forward as very good, good, fair, poor or very poor, but an effort from the local actors is crucial to guide what comes next.

5.3. Directions for Future Research

From the lessons learnt from the mapping of the three pilot territories of this research, the most suitable instruments to include RRI principles among the already available ones have emerged, as well as the dimensions that are generally under-developed and need more targeted actions. Such findings are not only at the basis for future considerations on how to better include RRI into territories, serving as a starting point for wider RRI-related discussions and researches, but they also might help other territories in performing the mapping exercise and in identifying the challenges and opportunities for the inclusion of RRI into their policy instruments and planning tools.

The methodology described and tested in this research has been validated, thanks to the involvement of partners of the SeeRRI project. However, it has been conceived to be applied to any additional territory that might be interested in the possibility of mapping the current level of inclusion of RRI into its regional development policies and urban planning instruments.

Some territories, which are part of the Network of Affiliated Territories (NAT) of the SeeRRI project, have expressed the interest in applying the mapping methodology. NAT members are from European states, associated countries and third countries with compositions that could mirror actors of the three focal territories regarding regional development policies, and innovation ecosystems, including, but not limited to, Badajoz, Haifa Municipality, Burgos, South-Eastern Europe, Ostrobothnia, Sardinia, Montenegro, and Southeast of Mexico. Extending this process to additional territories will allow to improve the methodology and to better detect the shortcomings.

Based on the previous considerations, it is recommended to others than the SeeRRI territories which may aim to conduct a mapping of their current RRI state-of-the-art in territorial policies and plans, to start from building a strong network of local stakeholders to look into the dataset available at territorial level in order to find connections with the RRI principles, and to always make an effort to self-evaluate their actions and plans. Such a process is dependent on concerted efforts from multiple actors and engagement with the specificities accorded by different cultures, be they public, private, or disciplinary [67]. Strong local networks with a clear identification of the stakeholders and their role; the presence of a monitoring system able to capture the impact of the initiatives foreseen in the policy instruments; and the access to open public datasets emerged as key elements that additional territories need to take into account before approaching the mapping exercise. Further research is needed to provide considerations on the level of maturity of RRI into regional development policies and urban planning instruments and the political, geographical and socio-economic characteristics.

Explicit inclusion of RRI into territorial development policies and strategies can make the concept more visible, raising people’s awareness of RRI principles and also implementing actions which are more focused and effective. In doing so, it could be possible for territories to become more inclusive and responsible, both in spatial planning and development strategies.

However, the actual impacts and benefits of RRI-related instruments need to be properly monitored and evaluated as policies and tools must be equipped with an effective monitoring system in order to be able to state if they need to be improved in the future and how. In this way, RRI might overcome its original boundaries and be embedded in a more effective way into place-based development instruments.

Author Contributions