Abstract

The Roma ethnic group represents an integral part of the Slovak population. Thanks to their specific customs and traditions, in combination with social segregation, they have kept several differences from the majority of the population. These differences have also been demonstrated in the conditions and quality of housing, which are the basic indicators of the economic and cultural maturity of an individual, as well as the nation itself. The goal of this paper is to examine the issue of the Roma population in the Slovak Republic, with a focus on the area of housing. In the historical excursion, the authors present the arrival of the Roma to Europe and subsequently the present territory of the Slovak Republic. They point out the importance of the Roma issue and what has caused the conditions and factors determining the development and position of this ethnic group at the periphery of the majority. Using the data from the Atlas of Roma Communities from 2019, they analyze the demographic behavior and reproduction of the Roma population, which differs from the reproduction behavior of the majority population, as well as the territorial displacement of the Roma. In the following sections of the paper, the authors focus on examining the housing conditions of the Roma community in individual regions of the Slovak Republic and the programmes aimed at improving the housing situation of the Slovak Roma.

1. Introduction

The social–economic transformation of the Slovak economy after 1989 caused a new social stratification of the population, and it deepened the differences in their living standards. The social policy had to react to radical social–economic changes with gradual legislative standards, by enforcing the principle of personal responsibility and participation, which also contributed to the deepening issues of the living standard of some groups of the population and their social exclusion. Non-social and ethnic groups suffered from the changes after November as much as the Roma [1,2]. During the difficult period of transformation, Roma issues have been transformed into the concept of the social inequality of the Roma community itself [3]. The social policy of the state gradually stopped applying the principle of personal policy to them and replaced this with the civil principle. Since this group of citizens were unqualified to an increased extent, its members were among the first to lose employment and became dependent on social support, which for many of them has lasted for more than 30 years.

In this, paper we focus our attention on the continuing issues of the Roma ethnic group in the area of housing in the Slovak Republic, which lead to strong social distancing, as well as proposals for measures for the improvement of the existing situation. Furthermore, we calculate the number of Roma in individual regions and process our basic findings on the housing question of the Roma communities, as well as the programmes leading to improvements in the housing situation of the Roma communities in the Slovak Republic. The Roma issue is one of 33the most discussed topics in our society, which is usually examined from a macro-economic perspective, by using legislature and other macro-economic and social frameworks, which create platforms for the examination of other social aspects. The most sensitive issues are linked to the reproductive behavior of the Roma, unemployment, increased crime, migration, the effectiveness of financial costs spent on social inclusion, misuse of the system of social protection and the housing question. A number of activities are focused on the Roma, which raise questions for the majority population on the meaningfulness of the spent financial resources and energy [1,4,5].

The Roma issue is the result of stigmatization and exclusion of the members of the Roma minority by the majority and the low social potential of this minority. The stigmatization of the Roma results in their marginalization, discrimination, and gradual exclusion from the society. Social exclusion is the primary barrier to equal opportunities [6]. Examinations of the aspects of social exclusion of the Roma were the subject of several studies [7,8,9,10,11]. Madanipour (2003) points out the fact that social exclusion could push the individual out of society [12]. Social exclusion refers to the multi-dimensional and dynamic process of exclusion from different spheres of life [6,13,14,15]. Social exclusion as a structural problem prevents equal access to resources, employment, regular income, and it causes poverty [6]. Poverty and the bad situation of the Roma are often manifested in substandard housing conditions in segregated villages, which often lack basic infrastructure.

During the period of building socialism, there was a general (not only for Roma) suppression of entrepreneurship and creativity and the state’s paternalistic orientation was reinforced. The state gradually took over the patronage of solving the Roma issue and excluded from cooperation those to whom these solutions should have applied, the Roma themselves. This material aid caused the gradual devastation of the Roma’s positive awareness, a loss of personal motivation and apathy. This fact had a major impact on the housing quality of the Roma.

Despite the fact that the housing of the Roma is the subject of many scientific discussions, a comprehensive concept for housing is missing. Using theoretical analysis of domestic and foreign sources, we present a historic view of the Roma issue. By analyzing documents, we have examined the legislative programmes leading to the improvement of Roma housing. In the empirical section, we use a secondary analysis, based on which we analyze the data regarding the type of housing as well as the housing conditions of the Roma residents. Using abstraction, we leave aside some parts and features of the examined topic to focus only on those characteristics that are significant for our focus. We formulate conclusions by generalizing them based on the examined indicators.

2. Theoretical Background and Historical View of the Roma Issue

The origin of the Roma is most likely in India [16], since the ancestors of the Roma were members of the lowest caste, the so-called Pariah. The departure of the Roma from India took place over several centuries in migratory waves. However, they have not stayed in individual countries for the same amount of time. Today, the duration of their stay in each country historically is determined based on the adoption of certain words in the Roma language.

The first record of the Roma in Central Europe is considered a record of an Austrian monk from the 12th century, who writes of them as globetrotters. The oldest record of their stay in Slovakia is from 1322, from the vicinity of Spišská Nová Ves. They have always preferred richer regions to poorer because they knew they could find a livelihood there. Their livelihood was mostly earned through assistant work, music and especially blacksmithing.

Several rulers have attempted the integration of the Roma. In 1761, Maria Theresa issued orders on the method of emancipation of the Roma [17]. Their final goal should have been their fast assimilation with other lieges. They were prohibited from living in chalets or marquises, wandering the region, conducting horse trades, or having their own vajdas or reeves. In 1782, Joseph II ordered the Roma to be educated and to heed to proper school attendance for their children. The Emperor further issued a requirement that they should be led towards farming. The rulers saw assimilation with the majority population and the suppression of differences between them and the rest of the population as the only ways to solve the Roma issue.

After the creation of the first Czecho-Slovakian Republic, there was an effort to introduce measures against nomadic Roma. In 1927, the Act on Wandering Gypsies was adopted [18], which specified the obligations to report to home villages and report on request, and it also introduced “Gypsy legitimations”. The Act regulated the conditions of nomadism, limited the movement of persons, specified the size of the nomadic group and defined locations for camping.

The Act became an example of legislative procedure for other European states and, in our territory, it was the first Act that required the social distancing of the majority population from the Roma. In the pre-Munich period, based on the application of the Act, there were persecutions of the Roma, discrimination, and special treatment of them. For example, based on the application of this Act, the Centre for Registration of Wandering Gypsies was established in Prague in 1928, which fell within the competence of the Ministry of the Interior. The individual provisions of the Act were in violation of the Constitution in force at the time, which guaranteed equality for the citizens of the Republic [19]. In 1969, the Committee of the Government for the Issues of the Gypsy Population and the Union of Gypsies–Roma was created at the Slovak Ministry of Work and Social Affairs [20].

Significant social changes in Europe and major increases in the Roma population in Europe have forced the broader public to take a deeper interest in their way of life, especially because the social, healthcare, education, housing and other issues of the Roma have increased. Hojsík [21] states: the issues of housing, education, employment, health condition and others are in mutual dialectic relation and are mutually conditioned. Millan and Smith [22], as well as Evans and Kim [23], have examined the factors of quality and type of housing and their impact on health. In our view, the Roma end up in a downward spiral due to the combination of these factors, from which there is almost no escape. With the passage of time, it must be stated that the directive on integration was not successful and was even harmful.

The intensification of the discourse on the topic of the Roma issue may lead, in parts of society, to the realization of the need for forthcoming solutions not only from the economic, but also the moral perspective as well; however, the accentuation of the discrimination of the Roma without considering the issues of the Slovak society as a whole can lead, among the less educated population, to the escalation of tensions against the Roma.

The issues of the Roma ethnic group depend, for the most part, on their integration into society and do not apply to their whole spectrum, only a certain part of their population. Three main groups of Roma can be differentiated in Slovakia based on their way of life. The first group consists of the socially most developed, most educated, and most qualified for work group, which does not significantly differ from the majority in its way of life. This includes Roma, which are dispersed or integrated throughout Slovakia. The most frequent problem they have to face is linked to their ethnicity. The second group consists of partially integrated Roma. Roma who could be included in this category have a reduced social status and more unstable job prospects. In some cases, the housing where they live does not significantly differ from that, where the first group lives; however, more often, they approach the limits of the living conditions of the third group. The third group of Roma live, for the most part, in Roma locations, settlements and ghettos, completely isolated from the majority of society, since the majority of society refuses to accept them and include them in their environment. Its members live in huts and dwellings of a low standard, which are built only as impermanent structures, without foundations, water, electricity and without a building permit. Another part lives in city ghettos, where the majority of the Roma in these locations have been gradually relocated. A significant number of them live on or below the poverty line and, for the most part, are only on state benefits and material need benefits [24]. In this group of Roma, the value of education is found in the lowest levels of the value scale [25]. The education of this group is at the lowest possible level, caused by the fact that a significant group of them did not complete even their primary education, which subsequently affects their employment prospects in the labor market.

The Roma population living in the territory of the Slovak Republic regularly appears among groups most endangered by poverty, social exclusion, and discrimination. Michálek [26] examined the poverty of the Roma, and specializes in the levels of Roma poverty and defined so-called cores of poverty in Slovakia, which, for the most part, are populated by the Roma minority. This ethnicity combines several disadvantages: there is poverty linked to demographic conditions, poverty created by unemployment, poverty caused by doing low-skilled and low-paid work, or a lack of education and discrimination. However, it must be emphasized that these problems do not apply to the entirety of the Roma ethnicity. According to Radičová [27], when taking into consideration the internal differentiation of the Roma, these problems are linked primarily to the so-called segregated Roma.

3. Methodology

The research topic in this scientific article is the issue of the demographic and reproductive behavior of the Roma population, which differs from the reproductive behavior of the majority population. The research problem is the spatial analysis of the obtained data in the context of examining the housing conditions of the Roma community in individual regions of the Slovak Republic and the identification of the number of Roma according to the types of settlements. Through a theoretical analysis of domestic and foreign sources, we have defined a historical perspective on Roma issues. By analyzing the documents, we examined the legislative programs leading to the improvement of Roma housing.

In the empirical part of the paper, we used a correlation analysis to examine the relationship between registered unemployment rate (%) and the share of the Roma minority in selected regions (Bratislava, Košice, Prešov and Banská Bystrica). A slight tendency towards the strong dependence between the unemployment rate and the share of the Roma minority in the examined region (Košice) was confirmed. The correlation coefficient r (x, y) expresses the relationship for a pair of quantities, x and y. It requires the expression of a combination of the mean and variance that characterize the behavior of each of the variables. This connection is expressed by statistical covariance—k (x, y), cov (x, y):

If we know k (x, y), then we can calculate the correlation coefficient:

The value of the correlation coefficient expresses a linear measure of the dependence of x and y. Its value takes values from −1 to 1. Furthermore, in the empirical part, we used a secondary analysis based on which we analyze data on the types of settlements as well as the housing conditions of the Roma population. Using abstraction, we looked away from some parts and features of the researched issue, so that we focused only on those characteristics that are essential to our focus.

For the analysis, we used the database of the Atlas of Roma Communities from 2019. The Atlas of Roma Communities provides data on the extent to which a specific Roma settlement is developed and segregated below average compared to localities inhabited by the majority. We selected several indicators to calculate the index of segregation and underdevelopment (Table 1). The conversion of the data in the selected columns into numerical values allowed us to create an index that organizes the sites in the order from zero (lowest level of segregation and underdevelopment) to 15 (highest level of segregation and underdevelopment) [28].

Table 1.

Indicators entering the index of segregation and underdevelopment.

The last part summarizes the conclusions found in the empirical sections on the basis of the examined indicators and presents recommendations for improving the existing situation in the field of Roma housing in Slovakia.

4. Results

Demographic Development of the Roma Ethnicity in the Slovak Republic

In determining the quantitative data on the number of Roma, we can start with the principle of self-identification of every individual or with the principle of assigned ethnicity. In Slovakia, the Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic works with the concept of self-identification in the creation and processing of ethnicity statistics. The number of Roma reported based on the principle of self-identification is usually called understated and inaccurate. The principle of assigned ethnicity operates via estimates of the number of people who are viewed as Roma in Slovakia. The problem lies in the fact that if a Roma is only a person who declares himself to be of Roma nationality, then we can state that there are only about 2% of Roma in the Slovak Republic [29,30,31], which in absolute numbers represents about 105,000 Roma (Table 2). Only a small percentage of the Roma living in Slovakia acknowledge their Roma origin. We can state that this number is relatively negligible, and it does not require special attention from the majority perspective. However, if we consider a Roma a person who is referred to as Roma by the majority of the population, then we can state that about 8% of the Slovak population is of the Roma ethnicity, which represents about 440,000 people [32]. This significant deviation occurs in that ethnicity has been recorded based on the principle of self-declaration of citizens by themselves. Marcinčin and Marcinčinová [33] present six main reasons why the Roma do not declare their Roma nationality in the census:

Table 2.

Population in the Slovak Republic (selected nationalities).

- -

- refusal to self-identify with a negatively valued social group; low social status of the Roma,

- -

- self-identification with the nationality of the (local) majority population,

- -

- failure to differentiate the terms nationality and state allegiance,

- -

- refusal of the term Roma as a social–political category, self-identification on the level of family and local community, in line with the deep-rooted cultural patterns, which are alien to the categories of nationality and ethnicity,

- -

- fear of possible misuse of declaration of the Roma nationality or fear of discrimination.

At the beginning of the 21st century, there was a significant shift in the practice of collecting data using the method of social–graphical territorial mapping of the Roma settlements. The mapping of the Roma communities in Slovakia (Atlas of Roma Communities) is based on the assumption that the marginalized Roma communities live in certain spatial units, enclaves, whether inside villages, at their outskirts or in segregated settlements, and therefore that the monitoring and mapping of these Roma communities is possible. This procedure is not in violation of the principles anchored in the Constitution of the Slovak Republic, and it is in line with the standards for the protection of personal data, because the mapping does not examine the ethnic identity of the individuals, only making an “inventory” of the settlement [32]. The Atlas of Roma Communities operates with qualified estimates and it is not an exact census from the methodological perspective. The estimates were provided primarily by the representatives of local self-governments, or other relevant informers. We are convinced that although the detection took place only in selected locations and the method of qualified estimates has been used, the deviation of the collected data is not statistically significant [3]. The goal of the Atlas of Roma Communities is the mapping of the infrastructure, access to services and of the overall social–economic conditions in the excluded and segregated environment of the Roma settlements. Currently, the most exact estimate is based on a survey conducted directly in the field [37] between December 2018 and March 2019, which mapped 818 villages and cities, in which it identified 416,039 Roma residents.

In this paper, we have used the data of the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019 to analyze the territorial structure of the Roma population. The largest representation of the Roma population is in the Košice region, where there are 133,988 Roma, followed by the Prešov region with 127,061 residents (Scheme 1). The lowest representations are in the Trenčín region with 8188 residents and the Žilina region with 8555 residents. In terms of age, residents aged 0–15 represent 21% of the Roma population and 14% of the population is aged 65 and over.

Scheme 1.

The number of Roma residents in regions of Slovakia. Source: own elaboration based on the data of the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019. [37]. Notes: regions in the Slovak Republic: BA—Bratislava region, Banská Bystrica region (BB), Trnava region (TT), Trenčín region (TN), Nitra region (NR), Poprad region (PO), Košice region (KE).

In Table 3, we list the villages with the highest share of the Roma population. Villages with a 100% share of the Roma population are found in the territory of the Košice region (Košice) and the Prešov region (Lomnička—County of Stará Ľubovňa). A large portion of the villages with a share of the Roma population between 98.9% (Sútor) and 90.0% (Kaloša) are found in the county Rimavská Sobota in the Banská Bystrica region.

Table 3.

Villages with the highest share of the Roma population (2019).

The demographic behavior and reproduction of the Roma population differs from the reproductive behavior of the majority population. Its most obvious manifestation is the different age structure of the Roma when compared to the rest of the population. The age structure of the Roma population was seen as very progressive at the end of the 19th century. The specific character of the reproductive behavior of the Roma population is affected primarily by the high natality rate, which is reflected in the age structure of the population. Table 4 clearly shows that the Roma population in Slovakia maintains its young age structure. There are no more than 10 seniors for every 100 Roma children. In the non-Roma population of Slovakia, the ratio between seniors and children continues to deteriorate. According to the latest census, it is almost 87%. The index of dependency of the young is considerably higher in the Roma population, given the high number and ratio of children, than in the non-Roma population.

Table 4.

The share of selected age groups and selected synthetic indicators in the Roma and the non-Roma population of Slovakia.

It is possible to assume that the number of Roma in Slovakia, as well as their share of the total population, will continue to grow, but not at the rate predicted by some politicians. In terms of possible threats, the development to a gradual ethnical domination of the Roma in some counties of Slovakia and the possible migration of the majority population from the marginalized regions are more dangerous. This may lead to the economic collapse of the counties if the Roma and Roma housing become dominant in these counties. A significant ethnicization of poverty may be expected within the next fifteen years, which may acquire a regional character. The unfavourable demographic development, when the population of Roma housing grows at an above average rate, may be reversed only under the assumption of improving the infrastructure of the Roma settlements.

The results of the census of population, houses and apartments of the Slovak Republic shows that, as of 21st May 2011, the Slovak Republic had 5,397,036 permanently residing residents. The population grew by 17,581 residents over a 10-year period. At the decisive moment of the census, of the total number of permanently residing citizens of the Slovak Republic, residents of Slovak nationality, had the greatest representation (80.7%, i.e., 4,352,775), Hungarian nationality (8.5%, i.e., 458,467) and the Roma nationality (2%, i.e., 105,738). In the inter-census period of 2001–2011, the number of permanently residing Roma residents increased the most in absolute numbers (15,818). The Roma are the only national minority in Slovakia, the members of which do not occupy any territory in Slovakia, and they do not even have a mother country [39]. From a demographic perspective, Slovakia is one of countries with the highest percentual representation of Roma. The Roma population in Slovakia is relatively young compared to the general population in terms of age structure and the average age as well. This status is caused by the low mortality age and the higher natality rate of the Roma compared to the majority population. Most residents of Roma nationality lived in the Prešov region (5.3%, i.e., 43,097). According to the results of the population, houses, and apartments census in 2011, there were 17 villages in Slovakia with more than 50% of residents of Roma nationality. The village with the highest share of permanently residing residents of Roma nationality was the village of Kesovce (83.3%, i.e., 194) in the county of Rimavská Sobota [29]. In assessing villages with a higher share of Roma, Ira [40] states that these are small and spatially displaced islands, whereby he warns of the fact that the share of the ethnic Roma is several times higher than the share of residents who declared Roma nationality. Table 1 shows that more and more residents are declaring Roma nationality, but the data on nationality does not take into consideration the actual status of the Roma ethnic group.

Vaňo [41] created a prognosis of the Roma population, which attempted to estimate the development of the Roma population by using the component method in three variants (low—integrating, medium—inertial, high—segregating). Based on this prognosis, in the medium variant and a theoretical migration of zero, the Roma population in the Slovak Republic by 2025 is estimated to be 524,052 people [4].

The Roma issue is not only a matter of the Slovak Republic; almost all European states face this issue. However, they are hampered by the lack of comprehensive statistics on the Roma. In the beginning, the European Commission prevented statistics on the Roma. Only towards the end of the 1990s did the European Commission recognize the issue of the Roma, which should be solved on the European level. The need for statistics on the Roma is becoming increasingly necessary, since many countries of the European Union begin to implement targeted programmes focused on the marginalized Roma communities. The estimates on the size of this community differ significantly and range between 10 and 12 million residents. Of these, about 6.2 million live in the European Union, with the majority in the Central and Eastern member states. Currently, the Roma population is the largest ethnic minority in Europe (Table 5).

Table 5.

Member states with the highest estimated number of Roma.

The adoption of the EU framework for intrastate strategies for Roma integration represents an unprecedented commitment of the member states of the European Union to support the integration of its Roma communities. The EU framework supports policies, the goal of which is to ensure the Roma and the non-Roma population have equal access to employment, education, healthcare and housing.

5. Housing of the Roma Ethnic Group in the Slovak Republic

The housing of the Roma community has been the subject of different studies for a long time [22,43,44,45,46,47]. Horváthová [1], in the 1960s, criticized the contemporary method of housing construction for the Roma, which did not solve the housing issue sufficiently. By analyzing the types of housing (Table 6), we have found, from the number of Roma, based on the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019, that more than 36% of residents of the community live in housing which is localized on the outskirts of a village. Almost 31% of the Roma residents live integrated and dispersed in the majority population and the rest in socially excluded communities in various types of housing: urban and rural concentrations, settlements localized on the outskirts of the city or the village and settlements that are spatially remote from the city or the village, separated by a natural or artificial barrier. It follows that almost 14% of the housing is segregated, which means that this housing is found outside of a village or a town.

Table 6.

Roma housing.

Compared to the Roma in other countries, the Slovak Roma live more often in settlements and on the outskirts of villages and towns [28,29,30,31,48,49]. The coexistence of the Roma and the non-Roma population is problematic, which causes friction in their mutual relationships [44]. The majority of the Roma live in apartment buildings and family houses in various parts of the city. Often the Roma and poor families of the non-Roma majority live next to each other. The living conditions are not good. Many families often live in small housing units. The Roma in higher classes live in ordinary brick houses. The middle class also live in brick houses and have a larger population. Almost 14% of the Roma live in segregated settlements, which means that these settlements are located outside of the village or the town (Table 7). They live in overcrowded settlements, usually in modest wooden huts. A lot of brick houses, wooden huts and shelters of various qualities can be seen in the settlements.

Table 7.

Numbers of residents living in individual types of housing.

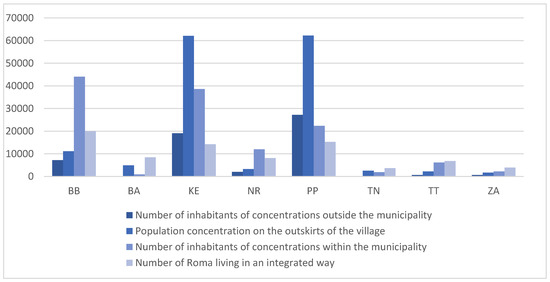

From a regional perspective, the majority of the Roma population is concentrated on the outskirts of villages, especially in the Košice region (62,108 residents) and Prešov region (62,242 residents). In the Košice region, in the Rožňava county, 11,378 residents live on the outskirts of a village, in the Gelnica county, it is 5207 residents. In the Prešov region, in the County of Prešov, 9378 residents live on the outskirts of a village and 2510 residents live in a village. In the county of Vranov nad Topľou, 12,223 of the 17,416 residents live on the outskirts of a village and 2232 live in a village. In the county of Kežmarok, 2498 residents live on the outskirts of a village. In the Košice and Prešov region, the highest number of residents live in a village. Most residents living in a village are in the Banská Bystrica region (44,060 residents); in the county of Lučenec, 2623 residents live in a village. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of Roma residents in regions of the Slovak Republic based on housing. Source: own elaboration based on the data of the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019 [37].

According to Šuvada [44] in some concentrated Roma groups, under persisting conditions, it is possible to expect a total resignation of the Roma to the morals, values, and normative framework of the majority of the population. The estimates say that the increase in the Roma population in some locations of our cities may indicate an increase in conflict, which is one of the reasons why the Roma are not a generally accepted and included part of Slovak society. Future estimates say that the number of people living in concentrated Roma groupings will grow in our cities. The main reason for this is the disproportionately high natality rate because the Roma community has a long-term high natality rate, and therefore a high rate of natural growth. This will lead to the overcrowding of some Roma districts, which will most likely lead to the even greater decline of whole areas of towns into the zone of social dependency and the related accumulation of associated problems, which will increase the urgency to solve the issues of concentrated Roma groupings in our towns [44]. Segregation distances the members of the disadvantaged group from the availability of services, such as postal services, shops, transportation, hospitals, etc. For this reason, it is desirable to implement the principle of desegregation, which is where a housing unit is placed integrally in the village or in a place that reduces the distances between the community and the main part of the village or town.

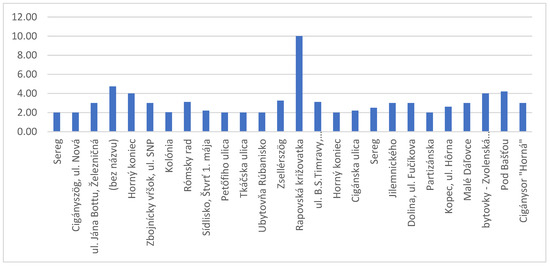

In connection with the previous findings, we also examined the index of segregation and underdevelopment. It is the segregation of Roma communities that is reflected in the quality of their housing. For the purposes of the survey, we used data from the Atlas of Roma Communities of 27 municipalities in the less developed region of Banská Bystrica, Lučenec District, with the highest number of Roma inhabitants. We found that the index of segregation and underdevelopment is in the range of two to 10 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Values of the segregation and underdevelopment index. Source: own elaboration based on the data of the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019 [37].

Roma concentrations are characterized by the absence of basic facilities, which are usually found in the non-Roma part of the village. Roma housing is often in a very poorly maintained and unhygienic condition. The spontaneous, rapid establishment of these settlements leads to a spatial absence of functional public areas and the communication between individual objects are unsuitable, which is linked to a plethora of other issues (for example, the frequent impossibility of waste disposal, which leads to the continued deteriorating condition of the environment [50]. There is also a high share of housing objects that do not pass building inspection requirements, or are in an unfit condition, such as shacks, caravans, unimobunka (note: unimobunka—container housing), etc. Almost 35,000 Roma residents live in shacks (Table 8) and more than 48,000 Roma live in masonry or wooden houses, which does not pass building inspections (Table 8). The conditions for the Roma population, whether in concentrations outside of a village, on the outskirts of a village or outside a village, do not have a positive impact on the quality of their life, which carries on from their quality of life in childhood. If children do not go to school, they become increasingly less employable in the labor market, which leads to them becoming unemployed.

Table 8.

Unfit types of housing and the population living in them—regional analysis, regions of the Slovak Republic.

There are long-term high unemployment rates in the counties of the Košice, Prešov and the Banská Bystrica regions. In 2019 in Rimavská Sobota, the rate was 15.14% (18.48%), Revúca 12.58% (14.88%), Kežmarok 14.79% (15.44%), Rožňava 12.14% (16.23%), Sobrance 11.35% (12.93%) and Medzilaborce 10.07%, (12.83%). In these counties, more than 35% of the population completed only basic education (counties in the East and South of Slovakia (Kežmarok, Námestovo, Revúca, Rimavská Sobota, Rožňava, Poltár, Gelnica and Košice—vicinity) and only 5% of the population completed university education (counties of Košice—vicinity, Námestovo, Poltár, Bytča, Gelnica, Čadca, Sabinov and Veľký Krtíš). The level of education of the population of these regions is related to the higher level of concentration of the Roma population (counties of Lučenec, Rimavská Sobota, Poltár, Revúca, Rožňava, Košice—vicinity and Kežmarok).

Districts are not using their potential. The untapped potential of less developed regions is also due to the relatively low activity of the Roma population in comparison with the remaining population or other countries in the region. The gradual deterioration of the labor market is reflected in the growing shortage of skilled workers, as the long-term unemployed suffer from a lack of skills. Every fourth jobseeker has not worked in these districts for more than 4 years. They are mainly low-skilled employees with the lowest level of education. This combination contributes to weak economic growth.

Using a correlation analysis, we examined the relationship between the registered unemployment rate (%) and the share of the Roma minority in selected regions (Bratislava, Košice, Prešov and Banská Bystrica). The values of the correlation coefficients for determining the dependence of the registered unemployment rate (%) and the share of the Roma minority in the selected region confirmed an indirect moderate to indirect strong dependence between the unemployment rate and the share of the Roma minority in the examined region (correlation coefficient Košice: 0.797686294; correlation coefficient Prešov: 0.806832269; correlation coefficient Banská Bystrica: 0.999999962; correlation coefficient Bratislava: 0.800989916). We can assume that, in regions with a high Roma population (Košice, Prešov, Banská Bystrica), the unemployment rate of the Roma is the highest and, conversely, in the Bratislava region, where the Roma make up a low percentage of the total population, unemployment rate is also the lowest. This fact is also caused by the fact that the Bratislava region has a low concentration of Roma settlements. An important reason for this is the fact that, in the Bratislava region, Roma have a better possibilities in the labor market, as there are job opportunities (construction work, work in hotels), while in the regions of Košice, Prešov or Banská Bystrica, there are not many job opportunities and, at the same time, there is also a high concentration of Roma. We state that there is a correlation, but cannot say that there is a causality between the studied variables.

The bad economic situation of the Roma in the villages causes the creation of non-standard settlements (simple dwellings made of wood, mud, sheet metal or other materials), which do not meet the technical or hygiene standards, and are built by the Roma themselves on land with unsettled legal status and without construction permits (Table 9).

Table 9.

Uninspected houses and the population living in them based on the regions of the Slovak Republic.

The fact that they stand on unsettled land results in basic infrastructure, such as water, electricity, sewerage, etc., not being brought to them. The Slovak Republic is trying to solve this embarrassing situation by amending Act No. 330/1991 Coll. on Landscaping, which means that, after the amendment, it will no longer be necessary to settle with every landowner individually and, instead, the whole village is dealt with under a joint action [51]. According to this amendment, it is sufficient to settle with the absolute majority of the owners, which should avoid situations where a couple of owners block the resolution of the settlement of the land. Settling the land of Roma villages has the following advantages:

- -

- satisfaction of the original owners, since the land will be settled,

- -

- satisfaction of the participating users, since land under the settlements in the Roma villages will be settled,

- -

- new organization of the land is possible through simple landscaping,

- -

- the development of the land will ensure the possibility of new construction,

- -

- there will be an increase in the income of the village through the property tax on the acquired land.

The main issues related to housing include access to drinking water, electricity, sewerage, municipal waste disposal and heating. Access to drinking water is considered a basic human right, which is also confirmed by the decision by the General Assembly of the UN from July 2010 [52]. Safe drinking water, together with access to sewerage, are “human rights, which are the foundations for a full life and for all other human rights” [3]. In 1042 monitored Roma locations, only 62% of housing is actually connected to and also uses public water supplies, 20% of the Roma use their own wells and 13% use public wells. Up to 6% of the monitored Roma population uses non-standard sources of water. This means that in the area of providing the population with drinking water, the situation is problematic for many groups of the Roma population. The problematic access to drinking water also suggests the fact that external water sources are not always found in the vicinity of Roma housing and therefore are quite a long distance away. The lack of quality drinking water is not only a question of survival, but it causes an overall social exclusion of the Roma population, which is manifested in poor health conditions, hygiene, attendance of children at schools and their results, as well as housing conditions. The regional perspective of the access to a water supply, wells, sewerage, gas and electricity is shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Housing conditions of the Roma population (based on regions of the Slovak Republic).

The Atlas of Roma Communities in Slovakia also helps in creating timelines, since the data from the Atlas of Roma Communities from the 2013 document showed that the public water supply was only used by 57% of the households of marginalized Roma communities. Only 23% used their own well and the rest used other sources, or they did not have access to drinking water at all. At the same time, access to fresh water, from the perspective of hygiene standards, co-creates the conditions for full participation in the life of a society. Only 32% of people actually use public sewerage, gas is actually used by 19% of people and 86% of marginalized people are connected to the electrical network.

According to Haraslinová [39], it is very important, even pressing, to improve the housing conditions and the present inhumane quality of life in some areas, in order to ensure, for example, school attendance, the hygiene of children, etc. In her opinion, these basic issues consist of the segregation that is significantly visible in these areas. However, it is not realistic to force so-called “urban mixing”, since the majority non-Roma community, as well as the Roma themselves, in most cases, do not want to live together. Upon the removal of existing settlements, great efforts and the rapid construction of housing, as well as facilities and infrastructure, are important. This requires not only state and local financial effort, but especially the rapid social and economic development of the Roma population. There is also the issue that the renewal or construction of residential houses and destroyed districts requires a large amount of finance. Assistance to villages and administrative authorities face misunderstandings on the part of the residents of the affected villages. However, the issues cannot be solved without this form of assistance.

In the programming period for the structural funds of the European Union 2014–2020, under the Human Resources Operational Programme, the use of mechanisms is envisaged, which would automatically authorize the villages with Roma settlements, with insufficiently developed infrastructure, to use financial resources to complete the construction of a water supply and sewerage. In this context, it is also necessary to consider the requirements of the EU Directive (91/271/EHS) on Municipal Wastewater Treatment. This imposes the obligation on member states to equip all locations with more than 2000 residents, where housing or agricultural activities are concentrated, with secondary municipal wastewater treatment [3].

5.1. Programmes Leading to Housing Improvement

The Slovak Republic attempted different forms of assigning apartments to the Roma, a process which was started by the socialist programme of liquidation of the Roma settlements. Different authors dealt with the issues of liquidation of the Roma settlements [53,54]. The results of this programme were devastated streets and districts, which had a bad impact on villages. One of the reasons for the failure of this programme was that the Roma themselves were not ready for such a rapid change to their lifestyle. Residents who moved to city apartments did not know, did not want or were not capable of using them properly, because thousands of Roma had lived in shacks until that point, some even in ground- or semi-ground-level dwellings. Their adaptation to life in the city environment was problematic [55]. According to Fulková [43], Roma from such a low social environment could not adapt to the life in panel apartment housing and this misunderstanding of the ethnopsychology of the Roma led to the fact that the provided apartments were often completely demolished and devalued. Only a couple of months after they moved into the apartments, many destroyed them. Since then, the public has very negatively perceived every possible initiative focused on the improvement of the housing conditions of the Roma. Therefore, these initiatives are considered politically very risky.

The transformation of housing after 1989 introduced major changes in the financing of housing and the housing policy of the state. Easily accessible loans and repayable grants for the construction of houses have been abolished. The right to housing was suddenly not granted by the “paternalistic” state (in the form of the policy of “assigning apartments”) and the acquisition of an apartment became a personal responsibility, just like with any other commodity in the market. The state-owned apartments were transferred to the villages and subsequently privatized. The tenants had the right to purchase their apartments for a low price set by the state. The majority of the tenants used this right before the end of the 1990s and, in most cases, only apartments where socially and economically weaker households lived remained in the ownership of the cities and villages [56]. This was also the case of many apartments in the historic centres of towns, inhabited by Roma. As these centres developed, this real estate became attractive, which led to efforts to force out the Roma tenants [57].

The main initiative of the Government of the Slovak Republic to improve the housing of families with lower income was the Housing Development Programme, which was adopted for the first time in 2001, and which was directed by the Ministry of Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic [58].

The state gradually created a system of supportive economic tools for housing development, which were differentiated based on the social situation of the applicants in relation to housing. The greatest and most effective support of the state was focused on supporting the construction of rental apartments for households with the lowest incomes and marginalized groups of the population. These supporting tools have been continuously modified. The maximum support of the state has been provided to villages and non-profit organizations for the construction of rental apartments for households, the income of which does not exceed three times the subsistence level. Support was provided in the form of subsidies of up to 30% of the procurement costs of construction, with the condition that the procurement costs per 1 m2 of the surface area of the flat did not exceed the maximum limit set by the regulation of the Ministry of Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic. To finance the rest of the costs of the construction, the investors could use a loan from the State Fund for Housing Development, with a low interest rate and a long repayment period. Other forms of support were rental apartments of a lower standard for citizens in material or social need. The condition for the acquisition of rental apartments of a lower standard was not to exceed the maximum limit of procurement costs per 1 m2 of surface area of the apartment, which, given the lower standard of equipment of the apartment, represents ca. 55% of the procurement costs of a standard apartment. These are apartments that are equipped with a sink, corner shower, flushing toilet, devices for the production of hot water and local heating.

The research of the Milan Šimeček Foundation in their “Evaluation of the Programme of Municipal Rental Apartments in Roma Housings” [57] pointed out the long-term unsolved issues of the Roma in connection to ensuring housing in villages and outside of them. One of the goals was to confront the field findings with the theoretical setting of the system of state support for housing development, specifically, the support of procuring municipal rental apartments for residents of Roma housing.

The Slovak Republic has learned from that and, today, it solves the unsuitable housing of the Roma by means of so-called transitional housing. Between 2014 and 2020, the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic, as the mediatory authority for part of the Human Resources Operational Programme (HROP), issued a call on 19th November 2018 focused on improving the forms of housing for villages with the presence of marginalized Roma communities with elements of transitional housing, a project which is co-financed by the resources of the European Fund for Regional Development [59]. The financial resources have aimed to support projects for the reconstruction and construction of residential buildings, which will be engaged in the multistage system of social housing in the form of rental housing with elements of transitional housing, whereby individual levels of this system must be accompanied by the work of housing assistants.

5.2. Transitional Housing

Transitional housing is based on the principle that the Roma will not abruptly move to apartments of a common standard, but that they will do this gradually, which means that they will live in a lower standard of housing at first and, subsequently, they then will move to a higher standard of housing, based on the merit principle. In this way, the Roma gradually learn to manage financial resources and also care for and maintain the apartment and common areas. However, the system works both ways, which means that in cases where the rules are violated, the client may be moved from a higher standard to a lower standard apartment. The second stage of the training consists of the supervision of the actions of the family, which means that they are monitored to see if the family members look for a job and if they pay their bills for the provided services.

In principle, the higher the housing standard:

- the higher the housing quality,

- the longer the rental agreement, which improves the stability of housing,

- the less supervision is necessary by social workers,

- the possibility of acquiring it is more difficult, since stricter assignment conditions are applied, for example, active participation of the household members in community activities or employment of at least one member of the household.

According to the view of the former Plenipotentiary of the Government of the Slovak Republic for Roma Communities, Ábel Ravasz, the long-term goal of transitional housing is to allow the households to enter the housing market by finding a rental apartment or through the self-help construction of a family house. The target groups are all vulnerable groups that require assistance in solving their housing issues and have the potential to improve their living standards through motivation [60].

The critics point out several shortcomings of the system of transitional housing. The system does not have the ambition to transition all clients into independent housing. Only about 30% and, in some cases, only 10–15% of the clients reach the highest level of housing. A large majority of the clients remain at lower housing levels in the long term [61].

The Slovak Republic allocated EUR 45 million from the European Union resources and more than EUR 5 million from the state budget resources for projects focused on improving forms of housing, with elements of transitional housing.

Transitional housing is not intended for all groups of the population, for example, for the handicapped and the homeless. For these groups, it will be more suitable to obtain apartments by means of so-called housing first, where the acquisition of housing is understood as the prerequisite for improved social–economic situations in other areas of life. A comparison of the selected aspects of the system of transitional housing and housing first is shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Comparison of the system of transitional housing and housing first aspects.

The Slovak Republic is characterized by a high rate of housing overcrowding, which, in 2017, reached 36.4%, while the average of the European Union is 15.3%. The rate of housing overcrowding in households with an income lower than 60% of the median is at 56%. One of the main explanations of the high overcrowding in the Slovak Republic is the numerous marginalized Roma communities. For this reason, we can consider the numerous groups of the Roma ethnic group in the Slovak Republic the so-called homeless. The significant lack of living space and cramped conditions are an ordinary part of the life of a significant number of the Roma population.

Housing in the housing first approach is understood as the basic need of every person, through the fulfilment of which the clients have the space and motivation to set other goals for areas in their life where they would like to see a change, with the help of a team of workers [62]. Housing first is not financially as difficult as transitional housing, since it does not include the construction costs and it lowers the usage of crisis services. Moreover, when comparing housing retention rates after the end of the provision of services, the success rate of housing first is twice as high as that of the transitional housing system [61].

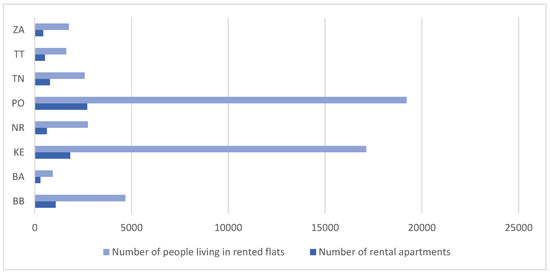

The state also helps to solve the unsatisfactory situation of Roma housing by different forms of support. The Housing Development Programme partially solves the situation, through which subsidies are provided for the procurement of rental apartments of common and lower standards, land preparation and the procurement of technical equipment, as well as for the removal of system failures in residential buildings. This programme is currently governed by Act No. 443/2010 Coll. [63] on Housing Development Subsidies and Social Housing. However, it is necessary to understand that this programme has its limitations and it will not solve all problems in the area of housing of marginalized Roma communities. The regional representation of the Roma population living in rental apartments is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Roma population living in rental apartments based on the regions of the Slovak Republic. Source: own elaboration based on the data of the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019 [37].

A significant share of the loan support pursuant to Act No. 150/2013 Coll. [64] of the State Fund of Housing Development was represented by support for the procurement of rental housing in the form of construction or purchase. The State Fund for Housing Development creates housing development programmes, which are not based on the division of the population into a majority and minority. This fund finances the priorities of the state housing policy approved by the Government of the Slovak Republic for the expansion and improvement of the housing fund. Members of the marginalized Roma communities are among the disadvantaged groups in the housing market, and for this reason, activities improving the housing fund are supported. Since 2018, the State Fund for Housing Development (2019) has provided support for the procurement of technical equipment for the financed apartments and for legal persons and entrepreneurs, and also the purchase of related land. A total of 83 applications for the procurement of a rental apartment have been delivered to the State Fund for Housing Development, of which 76 applications have been positively evaluated (Table 12). The procurement of a total of 76 residential buildings with 1487 apartment units have been supported. The value of loans granted was EUR 176,666,370 [65].

Table 12.

Success rate of applicants based on individual purposes (in %).

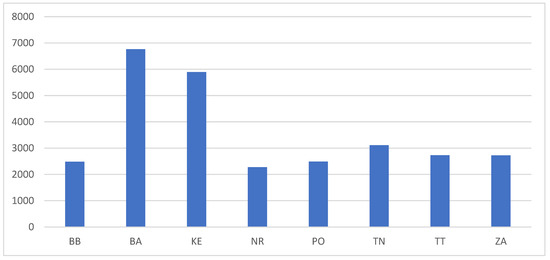

The regional representation of the number of supported housing units by the State Fund of Housing Development is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The number of supported housing units from the SFHD (State Fund of Housing Development) in individual regions in 2018. Source: own elaboration based on the data from SFHD 2019 [65].

A quantitative evaluation created by the Milan Šimeček Foundation [57] pointed to the fact that, in almost 92% of cases, the new rental apartments deepened the original spatial segregation, or the segregation remained at about the same level. The rental apartments represent a new financial burden for the tenants, since the amount of rent is far higher than the financial possibilities of the Roma population. If the Roma truly want to improve their own housing, society should offer a helping hand in the form of improving their education and integration in the labor market, and this will gradually lead to the improvement of their housing situation.

6. Conclusions

The Slovak Republic adopted the ‘Strategy for Roma Integration by 2020’, the goal of which is to create measures, which will ensure the improvement of the social inclusion of the marginalized Roma communities, as well as a reduction in their exclusion from other groups of the population. However, their marginalization is caused especially by their low level of education and qualifications, hidden discrimination on the part of employers, which causes high unemployment rates and, last but not least, by the low status of their housing and living conditions, which pushes them to the edge of society. Life in poverty, insufficient hygiene and very poor living conditions mean that the Slovak Republic is not only facing these issues on a local level, but also throughout the whole of Slovakian society.

In this paper, we have dealt with the issue of housing in the marginalized Roma minority. We have processed the newest data on the Roma communities living in Slovakia, based on the Atlas of Roma Communities of Slovakia 2019, which contains a broad range of data, however not all of the data have identical informative value. The realization of the heterogeneous nature of the data is necessary for their correct interpretation. Our analysis confirms that the conditions and quality of housing is at a low level. The Roma live in every third village in Slovakia. Most of them live in the Banská Bystrica, Košice and Prešov regions. The Roma live either integrated in the majority population directly, in the cities and villages, or, especially in the case of Eastern Slovakia, in settlements and dwellings on the outskirts of cities and villages. Based on the Atlas of Roma Communities 2019, more than 36% of community members live in housing that is localized on the outskirts of a village. In total, 31% of the Roma population lives integrated and displaced in the majority population and the rest live in socially excluded communities in the following types of housing: city and municipal concentrations, settlements localized on the outskirts of a city or village, settlements spatially removed from a city or village or segregated by natural or artificial barriers. This indicates that almost 14% of the housing is segregated, which means that this housing is found outside of a village or the town. The housing quality is of a very low standard, which is caused especially by non-existent or unsatisfactory infrastructure. The type of housing also affects the ability of the community to get help and support, since it makes stronger family ties and a more sociable lifestyle easier.

Satisfaction with housing affects one’s quality of life, the forming of one’s personality, a life of harmony, work and the spread of a positive attitude towards life. On the other hand, dissatisfaction with housing leads to the deepening of aggression and hate.

The improvement in the quality of life of the Roma population is in the interest of Slovakia, since it also improves the quality of life of the majority of the population. Attempts at improving the quality of life of the Roma by material assistance were tried before and they did not end with the desired effect. We have already seen in the previous regime that the Roma were assigned new apartments under the assumption that this would achieve their integration into society. However, this failed. These apartments were destroyed in a very short time and the level of housing returned to the original situation before the assistance. This also failed because these apartments were built, for the most part, on the outskirts of cities, which laid the foundations for the present concentrated Roma groupings. Here, the principle is that, in Roma settlements, material assistance without the necessary educational assistance is very ineffective. Housing is sustainable only if the future inhabitants are engaged in its preparation as much as possible and they are positively motivated to improve their housing situation by themselves. Successful housing policy in the context of integrating the Roma ethnic group must be based on the idea that new apartments must be dispersed in the majority environment and segregation should not be implemented by concentrating the apartments at a sufficient distance from the villages.

Effective assistance must be based on the idea that the Roma themselves can take care of themselves and their families. The majority population creates suitable conditions and tools for them, and shows them examples of good practice. For this reason, we propose to compile statistics on a regular basis, with the goal of monitoring the effectiveness of the support provided to the Roma, since it is alarming that the Slovak Republic has thus far spent substantial financial resources to solve the unfavourable situation of the Roma, and yet the situation continues to be unfavourable. Examples of good practice are in villages, where the self-governments strive to improve the quality of life and integration of the minority population in ordinary life through assistance, with the goal of engaging those residents in the self-help construction of their own housing.

We can present the activities in some villages as examples (for example, Rankovce, Spišský Hrhov). Otherwise, a significant part of the Roma minority living in segregated Roma settlements will continue to remain in a state of material need and the “scissors” between the majority and the Roma will continue to open. This trend will be reversed only under the assumption that the majority and its representatives will accept the costly financing of social programmes, accompanying the investments in infrastructure. Otherwise, poverty will be reproduced in Slovakia at a very rapid pace and the attempts at preventing the creation of visible islands of poverty, known as hungry valleys, will fail. Today, there is no actual supra-local mechanism and the government do not have a lot of possibilities to prevent the discrimination of the Roma minority where it occurs the most often—at the lowest level of state administration and self-government (unwillingness to hire Roma, unwillingness to allow construction, unwillingness to sell land, etc.)

The Roma issue is multidimensional and is mainly a specific issue of our society. Today, there are reasons for the Roma issue to remain the most-discussed topic in Slovakia. Should the status quo continue (weak engagement of the state without a viable plan), which is the non-standard and possibly regressive approach of the Slovak administration towards the Roma, without the implementation of development programmes, we should also expect issues in relation to other minorities. The completion of a system of social security based on the principle that it pays to work, which would focus on systematic assistance and satisfy the housing needs of the people, should be a challenge for politicians. To solve the housing issues of the Roma ethnicity, an expert discussion must take place, of which the Roma must make up an integral part.

In conclusion, we can state that the effort to improve the housing conditions in Slovakia is a long-term process. We are of the opinion that our results and findings have analytical potential; they are applicable across several social–scientific disciplines and may help policymakers in searching for solutions to the issues of the Roma ethnic group. It is our recommendation that members of the Roma minority participate in the resolution of their housing problems, especially through changes in their lifestyle at an early age. Correcting the habits of Roma children will lead to a change in their attitude to education, which guarantees that, in the future, they will be capable of taking care of their own needs and using their own resources, under the preserved assistance of the state.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; methodology, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; validation, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; formal analysis, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; resources, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; visualization, P.S., J.V. and E.R.; funding acquisition, P.S., J.V. and E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The paper is the output of the research grant VEGA no. 1/0251/19 “Households investments in housing and the possibility of their alternative use as additional income at the time of receiving the pension benefit” (50%) and VEGA no. 1/0037/20 “New challenges and solutions for employment growth in changing socio-economic conditions” (50%).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Horváthová, E. Cigáni na Slovensku; Slovenská Akadémia Vied: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gajdoš, P. K vybraným problémom transformácie sociálno-priestorovej situácie Slovenska v 90-tych rokoch. Sociológia 2001, 2, 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Belák, A.; Červenka, J.; Hrabovský, M.; Rilčák, R.; Findor, A.; Grill, J.; Hajská, M.; Hrustič, T.; Krekovičová, E.; Podolinská, T. Čierno-Biele Svety. Rómovia v Majoritnej Spoločnosti na Slovensku; Vydavateľstvo VEDA: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015; ISBN 978-80-224-1413-5. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvada, M.; Slavík, V. Prínos Slovenskej geografie do výskumu rómskej minority v Slovenskej republike. Acta Geogr. Univ. Comen. 2016, 2, 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Samko, E. Rómovia Včera, Dnes a Zajtra; Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa: Nitra, Slovakia, 2000; ISBN 80-8050-302-8. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, B. Social exclusion, social isolation, and the distribution of income. In Hills, John, Le Grand, Julian and Piachaud, David, eds. Understanding Social Exclusion; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, W. Between Past and Future: Roma of Central and Eastern Europe; Universtiy of Hertforshire Press: Hatfield, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch, P. Ethnic minority identity and movement politics: The case of the Roma in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2003, 5, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vašečka, M. Čačipen pal o Roma. Súhrnná správa o Rómoch na Slovensku; Inštitút Pre Verejné Otázky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002; ISBN 80-88935-41-5. [Google Scholar]

- Filčák, R. Living Beyond the Pale: Environmental Justice and the Roma Minority in Slovakia; CEU Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Filadelfiová, J. Situačná Analýza Vybraných Aspektov Životnej Úrovne Domácností Vylúčených Rómskych Osídlení; UNDP: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Madanipour, A. Social exclusion and space. In Madanipour, Ali, Cars, Goran, Allen, Judith, eds. Social Exclusion in European Cities: Processes, Experiences, and Responses; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. Social Exclusion; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, M.; Heady, C.; Middleton, S.; Millar, J.; Papadopoulos, F.; Room, G.; Tsakloglou, P. Poverty and Social Exclusion in Europe; Edward Elgar: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Akkan, B.; Baki, D.M.; Eratan, M. The Romanization of poverty: Spatial stigmatization of Roma neighborhoods. Turk. Rom. Stud. 2017, 1, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinaiová, A.; Ondriová, I. História a zdravie rómskej populácie. In Molisa 6: Medicínsko-ošetrovateľské listy Šariša; Prešovská univerzita v Prešove, Fakulta zdravotníctva: Prešov, Slovakia, 2009; ISBN 978-80-555-0048-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sika, P. Sociálno-ekonomické podmienky marginalizovaných rómskych komunít. Ekon. Spektrum 2013, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zákon Národního Shromáždění Republiky Československé z 14. Júla 1927 o Potulných Cigánech. 1927. Available online: https://www.noveaspi.sk/products/lawText/1/4450/1/2/zakon-c-117-1927-sb-o-potulnych-cikanech/zakon-c-117-1927-sb-o-potulnych-cikanech (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Rómske Dokumentačné a Informačné Centrum. Rómovia v Uhorsku v 19. Storočí a Zač. 20. Storočia. 2013. Available online: http://www.romadocument.sk/index.php/sk/dejiny-romov-naslovensku/romovia-v-uhorsku-v-19storoi-a-za-20storoia.html (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Kotvanová, A.; Szép, A.; Šebesta, M. Vládna Politika a Rómovia; Slovenský Inštitút Medzinárodných Štúdií: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hojsík, M.F. Evaluácia Programu Obecných Nájomných Bytov V Rómskych Osídleniach. 2008. Available online: https://www.nadaciamilanasimecku.sk/files/documents/publikacie/evaluacia%20programu%20obecnych%20najomnych.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Millan, M.; Smith, D. A Comparative Sociology of Gypsy Traveller Health in the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W.; Kim, P. Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status-health gradient. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popper, M.; Szeghy, P.; Šarkozy, Š. Rómska Populácia A Zdravie: Analýza Situácie na Slovensku; Fundación Secretariado Gitano: Madrid, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-692-5485-1. [Google Scholar]

- Poláková, E. Štúdia na Tému Etika A Rómska Problematika; Univerzita Konštantína Filozofa: Nitra, Slovakia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Michálek, A. Chudoba na lokálnej úrovni (Centrá chudoby na Slovensku). Geogr. Čas. 2004, 3, 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- Radičová, I. Hic Sunt Romales; Nadácia S.P.A.C.E: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrle, J.; Ivanov, A.; Grill, J.; Kling, J.; Škobla, D. Nejasný Výsledok: Pomohli Projekty Európskeho Sociálneho Fondu Rómom na Slovensku? UNDP: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2012; pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-80-89263-12-7. [Google Scholar]

- Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej republiky. Základné Údaje zo Sčítania Obyvateľov, Domov a Bytov 2011. Obyvateľstvo Podľa Národnosti; Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Antolová, D.; Halánová, M.; Janičko, M.; Jarčuška, P.; Reiterová, K.; Jarošová, J.; Madarasová Gecková, A.; Pella, D.; Dražilová, S.; HepaMeta Team. A Community-Based Study to Estimate the Seroprevalence of Trichinellosis and Echinococcosis in the Roma and Non-Roma Population of Slovakia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koupilová, I.; Epstein, H.; Holčík, J.; Hajioff, S.; McKee, M. Heath needs of the Roma population in the Czech and Slovak Republics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úrad Vlády Slovenskej Republiky. Stratégia Slovenskej Republiky pre Integráciu Rómov do Roku 2020; Úrad Vlády SR: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011; Available online: https://www.minv.sk/?strategia-pre-integraciu-romov-do-roku-2020 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Marcinčin, A.; Marcinčinová, Ľ. Straty Z Vylúčenia Rómov–Kľúčom K Integrácii Je Rešpektovanie Inakosti. 2009. Available online: https://www.iz.sk/download-files/sk/osf-straty-z-vylucenia-romov.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Slovenský Štatistický Úrad. Sčítanie Ľudu, Domov a Bytov 3.3.1991; Slovenský Štatistický Úrad: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej Republiky. Sčítanie Obyvateľov, Domov a Bytov 26.5.2001; Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej Republiky. Sčítanie Obyvateľov, Domov a Bytov 21.5.2011; Štatistický Úrad Slovenskej Republiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Úrad Splnomocnenca Vlády SR pre Rómske Komunity. Atlas Rómskych Komunít 2019; Úrad Splnomocnenca Vlády SR pre Rómske Komunity: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019; Available online: https://www.minv.sk/?atlas-romskych-komunit-2019 (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Slovenský Štatistický Úrad. Sčítanie Ľudu, Domov a Bytov 1.11.1980; Slovenský Štatistický Úrad: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Haraslinová, M. Bývanie pre marginalizované skupiny obyvateľstva. In Nehnuteľnosti a Bývanie; Slovenská Technická Univerzita v Bratislave: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; ISSN 1336-944X. [Google Scholar]

- Ira, V. Etnická a religiózna štruktúra obyvateľstva východného Slovenska a percepcia etnických a religióznych napätí. Geogr. Čas. 1996, 1, 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vaňo, B. Prognóza Vývoja Rómskeho Obyvateľstva v SR do Roku 2025; Edícia Akty; INFOSTAT—Inštitút Informatiky a Štatistiky: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002; Available online: http://www.infostat.sk/vdc/pdf/prognoza2025rom.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Európsky Dvor Audítorov. Politické Iniciatívy a Finančná Podpora Eú Na Integráciu Rómov: Výrazný Pokrok Za Posledné Desaťročie, No Ďalšie Úsilie Je Potrebné V Praxi; Úrad pre Vydávanie Publikácií Európskej Únie: Luxembourg, 2016; ISBN 978-92-872-5286-9. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR16_14/SR_ROMA_SK.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Fulková, E. Identita Rómov Cez Ich Kultúrnu Gramotnosť; Štúdio-dd: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1990; ISBN 80-967263-3-1. [Google Scholar]

- Šuvada, M. Rómovia v Slovenských Mestách; POMS: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015; p. 68. ISBN 978-80-8061-828-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, I. My Rómsky Národ—Ame Sam E Romane Džene; Petrus: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005; p. 258. ISBN 80-88939-97-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bernáth, G.; Havas, G.; Kállai, E.; Károlyi, J.; Kemény, I.; Kovács, A.; Messing, V.; Szuhay, P.; Vajda, I.; Wizner, B. The Gypsies/The Roma in Hungarian Society; Teleki László Foundation: Budapešt, Hungary, 2002; p. 174. ISBN 963-85774 6-0. ISSN 0866-1251. Available online: http://mek.oszk.hu/06000/06025/06025.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Jakoubek, M.; Hirt, T. Rómske Osady Na Východnom Slovensku Z Hľadiska Terénneho Antropologického Výskumu; Dolis s.r.o., Slovakia: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2008; p. 727. ISBN 978-80-969271-5-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ringold, D.; Orenstein, M.A.; Wilkens, E. Roma in an Expanding Europe: Breaking the Poverty Cycle, 1st ed.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Petrescu, D.C.; Oroian, I.G.; Safirescu, O.C.; Bican-Brișan, N. Environmental Equity through Negotiation: A Case Study on Urban Landfills and the Roma Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smatanová, K. Segregované romské koncentrace—současný stav a možné nástroje transformace. In Člověk, Stavba a Územní Plánování 8. ČVUT v Praze; Holubec, P., Ed.; Fakulta Stavební: Prague, Czech Republic, 2015; pp. 240–252. ISBN 978-80-01-05655-4. ISSN 2336-7687. [Google Scholar]

- Zákon Slovenskej Národnej Rady č. 330/1991 Zb. O Pozemkových Úpravách, Usporiadaní Pozemkového Vlastníctva, Pozemkových Úradoch, Pozemkovom Fonde a o Pozemkových Spoločenstvách v Znení Neskorších Predpisov. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1991/330/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Škobla, D.; Filčák, R. Social Solidarity, Human Rights and Roma: Unequal Access to Basic Resourcies in Central and Eastern Europe. In Reinventing Social Solidarity Across Europe; Ellison, M., Ed.; The Police Pres: Bristol, UK, 2011; pp. 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Jurová, A. Vývoj Rómskej Problematiky Na Slovensku Po Roku 1945; Goldpress Publishers: Bratislava, Slovakia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, W. The Attempt of Socialist Czechoslovakia to Assimilate its Gypsy Population. Ph.D. Thesis, Universtiy of Bristol, Bristol, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Uherek, Z. Cizinecké komunity a městský prostor v Českej republike. Sociol. Čas./Czech Sociol. Rev. 2003, 2, 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M. Housing Policy: An End or A New Beginning; OSI/LGI.: Budapest, Hungary, 2003; p. 461. ISBN 96-3941-946-X. [Google Scholar]

- Milan Šimècka Foundation; The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE); European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC). Forced Evictions in Slovakia—2006 (Executive Summary); Nadácia Milana Šimečku: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2007; Available online: http://www.nadaciamilanasimecku.sk/fileadmin/user_upload/dokumenty/Evictions_ENG_-_Web_version_22_Jan.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Ministerstvo Výstavby a Regionálneho Rozvoja Slovenskej Republiky. Uznesenie Vlády SR č. 335/2001 z 11. Apríla 2001. k Návrhu Programu Podpory Výstavby Obecných Nájomných Bytov Odlišného Štandardu, Určených pre Bývanie Občanov v Hmotnej Núdzi ako i Technickej Vybavenosti v Rómskych Osadách. Available online: http://www.romainstitute.sk/files/files/123.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Ministerstvo Vnútra Slovenskej Republiky. Výzva Zameraná na Zlepšené Formy Bývania pre Obce s Prítomnosťou Marginalizovaných Rómskych Komunít s Prvkami Prestupného Bývania—OPLZ-P06-SC611-2018-2. 2018. Available online: https://www.minv.sk/?aktualne-vyzvy-na-predkladanie-ziadosti-o-nenavratny-financny-prispevok&sprava=vyzva-zamerana-na-zlepsene-formy-byvania-pre-obce-s-pritomnostou-marginalizovanych-romskych-komunit-s-prvkami-prestupneho-byvania-oplz-po6-sc611-2018-2 (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- TASR. Prestupne Byvanie Nie je o Rozdavani Bytov. Available online: https://openiazoch.zoznam.sk/cl/191656/Prestupne-byvanie-nie-je-o-rozdavani-bytov (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Škobla, D. Systém Podpory Bývania a Príspevok Na Bývanie. Identifikácia Optimálneho Modelu Na Základe Skúseností Best Practice V Medzinárodnej Perspektíve; Inštitút pre Výskum Práce a Rodiny: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Škobla, D.; Csomor, G.; Ondrušová, D. Uplatniteľnosť Systému Prestupného Bývania a, Housing-First“v Podmienkach SR; Inštitút pre Výskum Práce a Rodiny: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zákon Národnej Rady Slovenskej Republiky č. 443/2010 Z. z. o Dotáciách na Rozvoj Bývania a o Sociálnom Bývaní v Znení Neskorších Predpisov. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2010/443/20140101 (accessed on 10 June 2020).