Assessment of Work Conditions in a Production Enterprise—A Case Study

Abstract

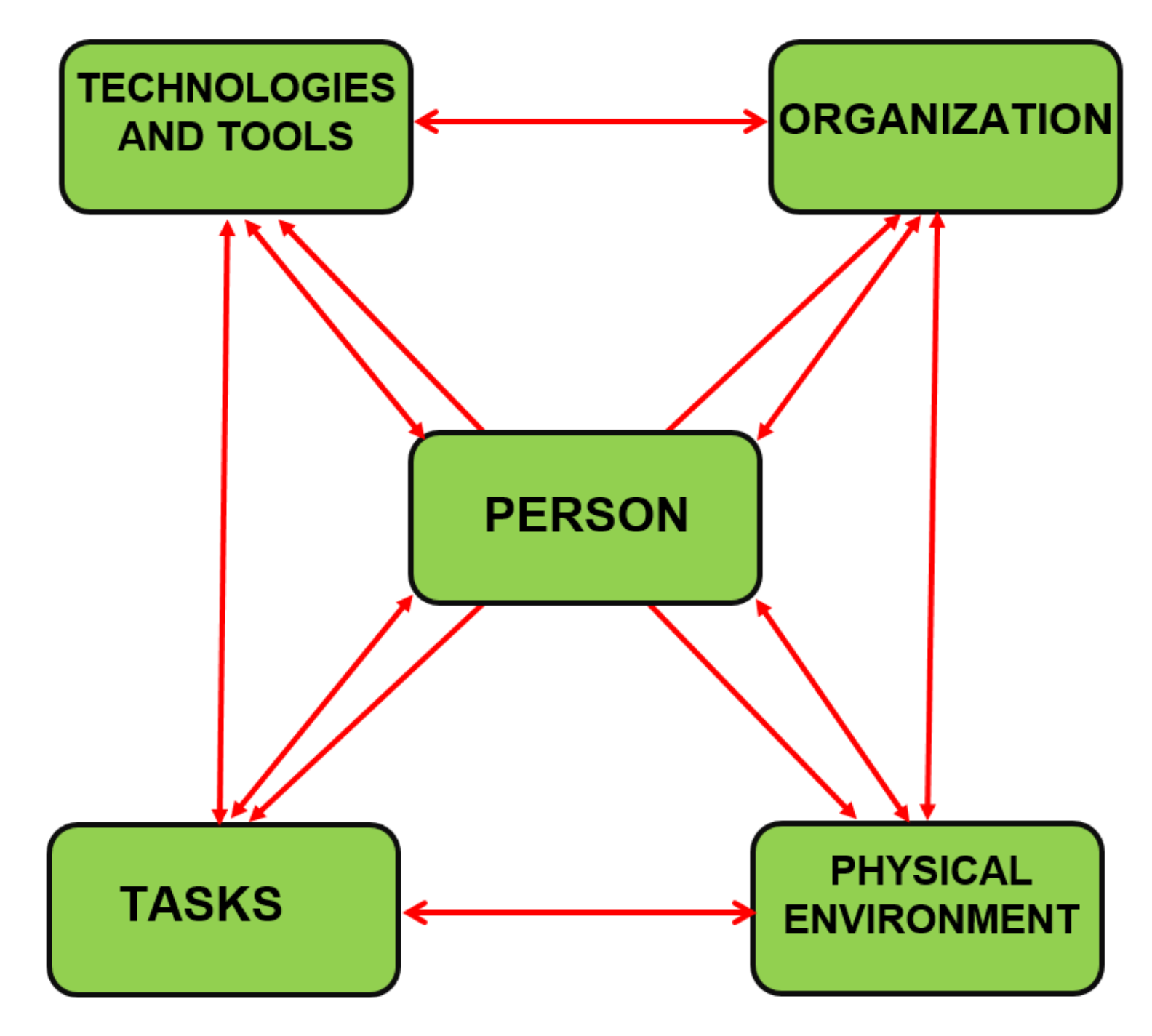

1. Introduction

1.1. Preliminaries, Objectives and Outline of the Study

1.2. Brief Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area of Research—Production Enterprise

2.2. Research Objective and Methodology

- -

- the characteristics of the work;

- -

- the human resource management policies;

- -

- the social context of the work.

2.3. Demographic Characteristics of the Surveyed Group of Employees

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Correlation Coefficient Between Selected Variables

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Characteristics of Work and Physical Work Conditions

3.4. Management Policy

3.5. Psychosocial Work Context

3.6. Efficiency and Creativity

3.7. Work Satisfaction

3.8. Stress at Work

3.9. Global Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- maintaining a work–life balance;

- -

- good work atmosphere in which the employee feels appreciated;

- -

- sense of job security (lack of uncertainty if the employee will be dismissed);

- -

- avoiding work in stress;

- -

- improving physical work conditions that are harmful and lead to sickness and absence of the employee, which generates additional costs;

- -

- preventing pay gaps.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | How many hours a day do you work (professionally)? |

| ☐ up to 6 h | |

| ☐ 7–8 h | |

| ☐ 9–10 h | |

| ☐ 11–12 h | |

| ☐ 13–14 h | |

| ☐ more than 14 h (how many?) | |

| 2 | Do you ever happen to work on Saturday? |

| ☐ I work nearly every Saturday | |

| ☐ I work every other Saturday | |

| ☐ ca. once a month | |

| ☐ ca. once in a quarter or even less often | |

| ☐ I never work on Saturday | |

| 3 | Do you ever happen to work on Sunday? |

| ☐ I work nearly every Sunday | |

| ☐ I work every other Sunday | |

| ☐ ca. once a month | |

| ☐ ca. once in a quarter or even less often | |

| ☐ I never work on Sunday | |

| 4 | Do you have time for leisure and relaxation? |

| ☐ I always have enough time for this | |

| ☐ I usually have the time | |

| ☐ I am sometimes short of time | |

| ☐ I am often short of time | |

| ☐ I generally do not have the time | |

| 5 | Do you feel your career adversely affects you private life? |

| ☐ definitely yes | |

| ☐ generally yes | |

| ☐ to some extent | |

| ☐ no | |

| ☐ definitely not |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you Have Poor Work Conditions as Regards: | Definitely Not | Not Really | Moderately | Considerably | Definitely |

| 1.1 | noise | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 1.2 | temperature | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 1.3 | lighting | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 1.4 | insufficient space | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Does your workplace have any of the elements that would be deemed repulsive or unpleasant by most people: dirt, dampness, objectionable smell? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely | Generally Yes | To Some Extent | No | Definitely Not | ||

| 1 | Do you have to work at a fast pace? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Does your job require intense effort? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Are you overloaded with work? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Does your work require lots of attention and focus? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | Does your work require good memory? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 6 | Does your work require solving complex problems? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 7 | Does your work require making quick and/or risky decisions? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No | Question | Response | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardly 1 | To Some Extent 2 | Moderately 3 | Considerably 4 | Definitely 5 | ||||

| 1 | My work… Allows me to make my own decisions on how to plan it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 2 | My work… Gives me a chance to draw upon my own initiative or opinion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 3 | My work… Allows me to choose methods used to complete my tasks | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 4 | My work… Provides me with clear, unambiguous information on my effectiveness (e.g. quality and quantity of my work) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 5 | My work… Provides me with information about my efficiency. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | My work… Provides me with feedback on the work I have done | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely Not | Not Really | Moderately | Considerably | Definitely | ||

| 1 | My work…Requires planning activities well in advance | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | My work…Requires making difficult organisational decisions | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | My work…Requires motivating others to achieve organisational objectives | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | My work…Requires supervising others | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5 | My work…Requires conforming to conflicting requirements | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No | Question | Response | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Definitely Not | Hardly Ever | Moderately | Considerably | Definitely | ||

| 1 | Do you have a chance to choose employees in the number and with the qualifications as required for the job? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2 | Do you have appropriate equipment in order to do your job? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3 | Do you have easy access to the information necessary to perform your job? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4 | Do you have the opportunity to obtain sufficient funds to perform the tasks assigned to you? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It Does Not Offer This Element at All 1 | Hardly 2 | Moderately 3 | Considerably 4 | It Definitely Offers This Element 5 | ||

| 1 | Competitive salary | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Salary that reflects the results of my work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Remuneration system and social package are related to the results | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | Bonuses are linked to the economic result of the whole organisation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | Fair system of extra perks and bonuses | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Employment agreement that guarantees secure employment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | Guarantee of keeping my job | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | Ability to participate in courses, trainings and workshops | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | Support in planning my future professional development | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | Ability to develop new skills and knowledge, which can be useful for my current work or in the future | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Hardly Agree 1 | I Slightly Agree 2 | I Somewhat Agree 3 | I Largely Agree 4 | I Definitely Agree 5 | ||

| 1 | The people I work with are friendly. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | The people I work with show me their interest. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | There are people at work who can understand and comfort me when times are tough. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | My superior shares information about my work with me. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | My colleagues inform me of my efficiency. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Other people in the organisation inform me about my efficiency. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | I can rely on my superiors to share the information I need to complete my work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | I can rely on my colleagues to share the information I need to complete my work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | I can rely on my superior to collaborate with me on the tasks I am supposed to complete. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | I can rely on my colleagues to collaborate with me on the tasks I am supposed to complete. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | I can assume that my superiors will make an effort to help me in a specific way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | I can assume that my colleagues will make an effort to help me in a specific way. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | I believe that my superiors consider me trustworthy and competent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | I believe that my colleagues consider me trustworthy and competent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Hardly Agree 1 | I Slightly Agree 2 | I Somewhat Agree 3 | I Largely Agree 4 | I Definitely Agree 5 | ||

| 1 | I properly complete the tasks assigned to me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I fulfil the obligations defined in my job description | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I complete the tasks that are expected of me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | At work I am practical: I suggest ideas that are useful for the organisation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | At work I am flexible: I try to adapt to the available resources in a creative way | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | At work I am creative: I come up with original ideas for my organisation. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardly 1 | To Some Extent 2 | Moderately 3 | Considerably 4 | Definitely 5 | ||

| 1 | Freedom to choose methods of work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Recognition I receive for a well done job | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Scope of responsibility assigned to me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | Opportunity to use my skills | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | Variety of tasks | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Physical conditions at workplace | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | My colleagues | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | My remuneration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | My working hours | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| No | Question | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never 1 | Hardly Ever 2 | Sometimes 3 | Quite Often 4 | Very Often 5 | ||

| 1 | Over the past month, how often did you feel nervous, because something unexpected happened at work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Over the past month, how often did you feel you do not control some important aspects of your life? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Over the past month, how often did you feel stressed or anxious because of work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | Over the past month, how often were you convinced that you could cope with difficulties at work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | Over the past month, how often did you feel that everything was going as it should at work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Over the past month, how often did you conclude that you cannot cope with all of your tasks at work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | Over the past month, how often were you able to contain the irritation related to your work? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | Over the past month, how often did you feel that the progress of tasks at work is just as you had assumed? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | Over the past month, how often were you angry because something that happened at work was beyond your control? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | Over the past month, how often did you feel that there were so many problems at work that you simply could not cope? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | Generally speaking, I have the opportunity to share my opinion about my work with my superiors, as well as to report any defects or proposed improvements without fear of ridicule or criticism | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | Generally speaking, the equipment and place where I work are appropriate and suitable for me to perform by tasks | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | Generally speaking, the way my superiors organise work makes it possible for me to perform my tasks properly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | Generally speaking, I feel my superior treats me fairly and evaluates my work properly. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | Generally speaking, I am fine with the atmosphere among my colleagues at work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16 | Generally speaking, I feel that my work is noticed, recognised and appreciated by my superiors. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 17 | Generally speaking, I feel I am overloaded with work and taken advantage of by my superiors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 18 | Generally speaking, I can count on my colleagues’ help and support at work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19 | Generally speaking, I can count on my superiors’ help and support at work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | Generally speaking, U am satisfied with my remuneration. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 21 | Generally speaking, my weekly and weekend roster is good for me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 22 | Generally speaking, the company gives me opportunity for personal development | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Varible | Response |

|---|---|

| Sex | ☐ 1. Male ☐ 2. Female |

| Age | ☐ 30 or younger ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 ☐ 51–60 ☐ 61 or more |

| Education | ☐ primary ☐ junior high school ☐ secondary ☐ vocational ☐ higher/university |

| Professional category | ☐ production worker ☐ administration/office employee ☐ foreman ☐ managerial job ☐ Other. Please specify……………………………………………… |

| Form of employment (you can choose a few options) | ☐ indefinite employment agreement ☐ fixed-term employment agreement ☐ part-time employment agreement ☐ contract of mandate, contract of specific work ☐ self-employment/running one’s own business ☐ remote work ☐ replacement employment agreement ☐ temporary work/employment under a temporary work agency ☐ seasonal job |

| Duration of the current agreement | …………………………………………………. Please enter the duration of the current agreement in years and months |

| How much time you have been working on this job | ☐ less than 5 years ☐ 6–10 years ☐ 11–15 years ☐ more than 16 years |

| Do you hold a managerial position: ☐ yes ☐ no? If yes, how many people are there in your team? ……………….. | |

Appendix B

References

- Vera, I.; Langlois, L. Energy indicators for sustainable development. Energy 2007, 32, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasibulina, A. Education for Sustainable Development and Environmental Ethics. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 2015, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, S. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, P.; Brown, D.; Hughes, M. Measuring resilience and recovery. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 447–460. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux, L.; Brown, C.; Wagner, L.; Foster, J. Measuring resilience in energy systems: Insights from a range of disciplines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Murcka, B. Sustainable development in the mining industry: Clarifying the corporate Perspective. Resour. Policy 2000, 26, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharčíková, A.; Mičiak, M. Human Capital Management in Transport Enterprises with the Acceptance of Sustainable Development in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green Human Resource Management as a Tool for the Sustainable Development of Enterprises: Polish Young Company Experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oginni, O.S.; Omojowo, A.D. Sustainable Development and Corporate Social Responsibility in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Industries in Cameroon. Economies 2016, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininia, G.; Ramezani, A. Factors Influencing Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Iran: A Case Study of Food Industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaskova, K.; Kliestik, T.; Svabova, L.; Adamko, P. Financial Risk Measurement and Prediction Modelling for Sustainable Development of Business Entities Using Regression Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, M.J.; Sutherland, W. An exploration of measures of social sustainability and their application to supply chain decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Tulder, T. International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P.; Hundt, A.S.; Karsh, B.-T.; Gurses, A.P.; Alvarado, C.J.; Smith, M.; Brennan, P.F. Work system design for patient safety: The SEIPS model. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, S.O.; Östberg, O. Working conditions and environment after a participative office automation project. Int. J. Ind. Ergonom. 1995, 15, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.-C.; Madhavan, R.; Righetti, L.; Smart, W.; Chatila, R. The Impact of Robotics and Automation on Working Conditions and Employment. IEEE Robot. Automat. Magaz. 2018, 6, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. Relationship between Job Satisfaction, Working Conditions, Motivation of Teachers to Teach and Job Performance of Teachers in MTs, Serang, Banten. J. Mgmt. Sustain. 2015, 141, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.B.; Zivin, K.; Walters, H.; Ganoczy, D.; MacDermid Wadsworth, S.; Valenstein, M. Factors Associated with Civilian Employment, Work Satisfaction, and Performance Among National Guard Members. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saurin, T.A.; Ferreira, C.F. The impacts of lean production on working conditions: A case study of a harvester assembly line in Brazil. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2009, 39, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining Structural Relationships between Work Engagement, Organizational Procedural Justice, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovative Work Behavior for Sustainable Organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, T.S.; Jeyapaul, R.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Evaluation of ergonomic working conditions among standing sewing machine operators in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2019, 70, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diant, I.; Salimi, A. Working conditions of Iranian hand-sewn shoe workers and associations with musculoskeletal symptoms. Ergonomics 2014, 7, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M.; Girard, S.A.; Simard, M.; Larocque, R.; Leroux, T.; Turcotte, F. Association of work-related accidents with noise exposure in the workplace and noise-induced hearing loss based on the experience of some 240,000 person-years of observation. Anal. Accid. Prev. 2008, 40, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbott, E.; Helmkamp, J.; Matthews, K.; Kuller, L.; Cottington, E.; Redmond, G. Occupational noise exposure, noise-induced hearing loss, and the epidemiology of high blood pressure. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 121, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminski, M.; Bourgine, M.; Zins, M.; Touranchet, A.; Verger, C. Risk factors for Raynaud’s phenomenon among workers in poultry slaughterhouses and canning factories. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzanello, M.R.; Moro, A.R. Increase of Brazilian productivity in the slaughterhouse sector: A review. Work. J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2012, 41, 5446–5448. [Google Scholar]

- Tirloni, A.S.; Dos Reis, D.C.; Dos Santos, J.B.; Reis, P.F.; Barbosa, A.; Moro, A.R. Body discomfort in poultry slaughterhouse workers. Work 2012, 41, 2420–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, F. Work–life balance: Contrasting managers and workers in an MNC. Empl Relat. 2007, 29, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakandi, M.; Behery, M. Sustainable human resources: Examining the status of organizational work–life balance practices in the United Arab Emirates. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.J. Work–life balance in the Australian and New Zealand surveying profession. Struct. Surv. 2008, 26, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, L.; Langford, P. Work–life balance or work–life alignment? A test of the importance of work-life balance for employee engagement and intention to stay in organisations. J. Manag. Organ. 2008, 14, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Shen, Y.-M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Chen, Q.; See, L.-C. Effects of Co-Worker and Supervisor Support on Job Stress and Presenteeism in an Aging Workforce: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoro, L.; Useche, S.; Alonso, F.; Cendales, B. Work Environment, Stress, and Driving Anger: A Structural Equation Model for Predicting Traffic Sanctions of Public Transport Drivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J. Associations of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Components of Work Stress with Health: A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, V.; Chinnadurai, J.S.; Lucas, R.A.I.; Kjellstrom, T. Occupational Heat Stress Profiles in Selected Workplaces in India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Building sustainable organizations: The human factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Speth, J.G. Towards a new economy and a new politics. Solutions 2010, 1, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Longoni, A.; Golini, R.; Cagliano, R. The role of New Forms of Work Organization in developing sustainability strategies in operations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.; Cheung, L.; Mak, A.; Leung, L. Confucian thinking and the implications for sustainability in HRM. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2014, 6, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maley, J. Sustainability: The missing element in performance management. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2014, 6, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Sustainable human resource strategy: The sustainable and unsustainable dilemmas of retrenchment. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2003, 30, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. The harm indicators of negative externality of efficiency focused organizational practices. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2012, 39, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Health harm of work from the sustainable HRM perspective: Scale development and validation. Int. J. Manpow. 2016, 37, 924–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S.; Kramar, R. Sustainable HRM: The synthesis effect of high performance work systems on organisational performance and employee harm. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2014, 6, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrewijk, M.V. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Silvestre, B.S. Managing stakeholder relations when developing sustainable business models: The case of the Brazilian energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccann, J.T.; Holt, R.A. Servant and sustainable leadership: An analysis in the manufacturing environment. Int. J. Manag. Pr. 2010, 4, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccann, J.; Sweet, M. The perceptions of ethical and sustainable leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, K.K.; Sen, S. Incenting managers toward the triple bottom line: An agency and social norm perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Christ, G.; Remer, A. Um Welt wirt schaft oder wirt schafts € okologie?Vorüberlegungen zu einer theorie des ressource nmanagements. In Betriebliches Umweltmanagement im 21; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zaugg, R.J.; Blum, A.; Thom, N. Sustainability in Human Resource Management; Institute for Organisation und Personel, University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2001; Working Paper No. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.; Santos, F.C.A. Continuing the evolution: To-wards sustainable HRM and sustainable organizations. Bus. Strat. Ser. 2011, 12, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Boselie, P.; Paauwe, J. The relationship between perceptions of HR practices and employee outcomes: Examining the role of person-organization and person-job fit. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widerszal-Bazyl, M.; Cieślak, R. Psychospołeczne Warunki Pracy: Podręcznik Kwestionariusza; CIOP: Warszawa, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment as Predictors of Organizational Citizenship and In-Role Behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Cummings, A. Employee creativity: Personal and Contextual Factors at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.L.; Rout, U.; Faragher, B. Mental Health, Job Satisfaction, and Job Stress among General Practitioners. Br. Med J. 1989, 298, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkowska-Smolak, T.; Grobelny, J. The design and preliminary psychometric analysis of the perceived stress at work questionnaire. Psychol. J. 2016, 22, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.; Cook, J.; Wall, T. Scales for the measurement of some work attitudes and aspects of psychological well-being. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1979, 52, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-P.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Lan, M.-Y.; Chen, H.-S. Examining the Moderating Effects of Work–Life Balance between Human Resource Practices and Intention to Stay. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, H.J.; Collins, M.K.; Shaw, D.J. The relation between work-family balance and quality of life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Luo, X.; He, X.; Yin, W. Development of Construction Workers Job Stress Scale to Study and the Relationship between Job Stress and Safety Behavior: An Empirical Study in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, N.; Cao, J.; Lim, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Kitahara, S.; Ishida, S.; Kodama, K. The Effects of Psychological Factors on Perceptions of Productivity in Construction Sites in Japan by Worker Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idrees, M.D.; Hafeez, M.; Kim, J.-Y. Workers’ Age and the Impact of Psychological Factors on the Perception of Safety at Construction Sites. Sustainability 2017, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smids, J.; Nyholm, S.; Berkers, H. Robots in the Workplace: A Threat to—or Opportunity for—Meaningful Work? Philos. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.Y.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of job stressors and stress on the safety behavior and accidents of construction workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.M.; Dearmond, S.; Chen, P.Y. Role of safety stressors and social support on safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2014, 64, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-Y. A Study of the Health-Related Quality of Life and Work-Related Stress of White-Collar Migrant Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3740–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, J.C.; Willyerd, K. The 2020 Workplace: How Innovative Companies Attract, Develop and Keep Tomorrow’s Employees Today; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gratton, L. The Shift: The Future of Work is Already Her; Collins: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Kozłowski, S.; Nazar, K. Wprowadzenie do Fizjologii Klinicznej; PZWL: Warszawa, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- O’ Neal, E.K.; Bishop, P. Effects of work in hot environment on repeat performance of multiply of simple mental tasks. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Liukkonen, P.; Cartwriht, S. Stress Prevention in the Workplace. Assessing the Costs and Benefits for Organisations; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxemburg, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Merecz, D. Psychospołeczne cechy pracy: Stresory i czynniki pozytywne. In Psychospołeczne Warunki Pracy Polskich nauczycieli. Pomiędzy Wypaleniem Zawodowym a Zaangażowaniem; Pyżalski, J.Ł., Merecz, D., Eds.; Impuls Publish House: Krakow, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter, S.L.; Hurrell, J.J. Occupational health psychology: Origins, content, and direction. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 1999, 30, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Variable | Variable Indicator | Source Measuring Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sociodemographic factors: age, gender, level of education, professional category, form of employment, duration of contract, length of service in the current position, managerial position held, scope of management | Responses given in the PI form | Personal information form—self-devised |

| 2 | Work characteristics: working time, work–home balance, physical work conditions, work requirements, autonomy, feedback from work, management functions, possibility of obtaining resources | Result on the measuring scale | Questionnaire on psychosocial work conditions [57] |

| 3 | Management policy: remuneration, additional bonuses, employment security, development opportunities | Result on the measuring scale | Questionnaire on perceived HR practices [57] |

| 4 | Psychosocial work context: work atmosphere, support from the supervisor, support from colleagues, feedback from the supervisor, feedback from colleagues | Result on the measuring scale | Questionnaire on psychosocial work conditions [58,59] |

| 5 | Performance (work efficiency) | Result on the measuring scale | Performance scale [60] |

| 6 | Creativity | Result on the measuring scale | Creative performance scale [61] |

| 7 | Satisfaction with work: internal, external and global | Result on the measuring scale | Work satisfaction scale [61] |

| 8 | Stress at work | Result on the measuring scale | Questionnaire on stress at work [62] |

| 9 | Global assessment | Result on the measuring scale | Questionnaire—own elaboration |

| Age | N | % |

| Up to 30 years old | 4 | 10 |

| 31–40 years old | 18 | 45 |

| 41–50 years old | 12 | 30 |

| 51–60 years old | 6 | 15 |

| Education Level | N | % |

| Middle school (junior high) | 1 | 2.5 |

| High school | 21 | 52.5 |

| Vocational | 13 | 32.5 |

| University | 4 | 10 |

| Incomplete data | 1 | 2.5 |

| Variable | Age | Physical Work Conditions —Noise | Requirement —Fast Pace | Autonomy | Management Policy —Salary | Psychosocial Context of Work | Productivity | Satisfaction | Stress | Global Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.000 | −0.2324 | 0.107 | −0.0556 | −0.0560 | −0.3485 | 0.166 | 0.022 | −0.0142 | 0.070 |

| p = --- | p = 0.144 | p = 0.507 | p = 0.730 | p = 0.728 | p = 0.026 | p = 0.301 | p = 0.891 | p = 0.930 | p = 0.664 | |

| Physical work conditions —noise | −0.2324 | 1.000 | −0.5677 | 0.063 | −0.3696 | −0.1181 | 0.0453 | −0.0472 | 0.120 | 0.062 |

| p = 0.144 | p = --- | p = 0.000 | p = 0.698 | p = 0.017 | p = 0.462 | p = 0.779 | p = 0.770 | p = 0.455 | p = 0.702 | |

| Requirement —fast pace | 0.107 | −0.5677 | 1.000 | 0.286 | 0.626 | 0.461 | −0.3194 | 0.414 | 0.4610 | 0.118 |

| p = 0.507 | p = 0.000 | p = --- | p = 0.070 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.042 | p = 0.007 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.463 | |

| Autonomy | −0.0556 | 0.063 | 0.286 | 1.000 | 0.352 | 0.149 | 0.127 | 0.339 | −0.2095 | 0.037 |

| p = 0.730 | p = 0.698 | p = 0.070 | p = --- | p = 0.024 | p = 0.352 | p = 0.428 | p = 0.030 | p = 0.189 | p = 0.821 | |

| Management policy —salary | −0.0560 | −0.3696 | 0.626 | 0.352 | 1.000 | 0.414 | −0.3862 | 0.441 | −0.5360 | 0.176 |

| p = 0.728 | p = 0.017 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.024 | p = --- | p = 0.007 | p = 0.013 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.272 | |

| Psychosocial context of work | −0.3485 | −0.1181 | 0.461 | 0.149 | 0.414 | 1.000 | −0.464 | 0.305 | −0.4490 | 0.070 |

| p = 0.026 | p = 0.462 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.352 | p = 0.007 | p = --- | p = 0.002 | p = 0.053 | p = 0.003 | p = 0.666 | |

| Productivity | 0.166 | −0.0453 | −0.3194 | 0.127 | −0.3862 | −0.4642 | 1.000 | −0.1045 | 0.441 | 0.144 |

| p = 0.301 | p = 0.779 | p = 0.042 | p = 0.428 | p = 0.013 | p = 0.002 | p = --- | p = 0.515 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.369 | |

| Satisfaction | 0.022 | −0.0472 | 0.414 | 0.339 | 0.441 | 0.305 | −0.105 | 1.000 | −0.4264 | 0.407 |

| p = 0.891 | p = 0.770 | p = 0.007 | p = 0.030 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.053 | p = 0.515 | p = --- | p = 0.005 | p = 0.008 | |

| Stress | −0.0142 | 0.120 | −0.4610 | 0.2095 | −0.5360 | −0.4490 | 0.441 | −0.4264 | 1.000 | 0.021 |

| p = 0.930 | p = 0.455 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.189 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.003 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.005 | p = --- | p = 0.896 | |

| Global assessment | 0.070 | 0.062 | 0.118 | 0.037 | 0.176 | 0.070 | 0.144 | 0.407 | 0.021 | 1.000 |

| p = 0.664 | p = 0.702 | p = 0.463 | p = 0.821 | p = 0.272 | p = 0.666 | p = 0.369 | p = 0.008 | p = 0.896 | p = --- |

| Physical Work Conditions | Descriptive Statistics | Points in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–4 | 3 | 1–2 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Favorable Result | |

| Noise | 1 | 5 | 3.39 | 1.14 | 51.22% | 31.71% | 17.07% |

| Temperature | 1 | 5 | 3.68 | 1.13 | 68.30% | 17.07% | 14.63% |

| Lighting | 1 | 5 | 2.58 | 0.98 | 12.20% | 41.46% | 46.34% |

| Small amount of space | 1 | 5 | 2.50 | 1.13 | 20.00% | 25.00% | 55.00% |

| Dirt, humidity, unpleasant smell | 1 | 5 | 2.32 | 1.11 | 12.20% | 21.95% | 65.85% |

| Factor | Descriptive Statistics | Points in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–10 | 11–15 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Favorable Result | |

| Physical requirements at work | 3 | 12 | 6.49 | 2.58 | 56.10% | 36.59% | 7.32% |

| Factor | Descriptive Statistics | Points in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–8 | 9–13 | 14–20 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Favorable Result | |

| Cognitive requirements | 4 | 16 | 8.66 | 2.89 | 46.34% | 46.34% | 7.32% |

| Factor | Descriptive Statistics | Points in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–10 | 11–15 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Favorable Result | |

| Autonomy | 3 | 14 | 8.56 | 3.38 | 26.83% | 39.02% | 34.15% |

| Human Resource Management Policy | Descriptive Statistics | Scoring in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–10 | 11–15 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Advantageous Result | |

| Remuneration | 3 | 13 | 6.71 | 2.81 | 45.00% | 45.00% | 10.00% |

| Bonus | 2 | 10 | 4.76 | 2.05 | 48.72% | 43.59% | 7.69% |

| Employment safety | 2 | 10 | 6.02 | 2.14 | 17.95% | 56.41% | 25.64% |

| Development | 3 | 13 | 8.02 | 3.15 | 30.77% | 43.59% | 25.64% |

| Factor | Descriptive Statistics | Scoring in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–10 | 11–15 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Advantageous Result | |

| Atmosphere | 3 | 13 | 7.44 | 2.84 | 41,.46% | 41.46% | 17.07% |

| Supervisor’s support | 3 | 14 | 7.51 | 3.49 | 43.90% | 29.27% | 26.83% |

| Coworkers’ support | 3 | 13 | 8.76 | 3.11 | 14.63% | 36.59% | 48.78% |

| Information from the supervisor | 2 | 10 | 5.17 | 2.25 | 48.78% | 31.71% | 19.51% |

| Information from coworkers | 2 | 8 | 5.32 | 1.75 | 31.71% | 58.54% | 9.76% |

| Factor | Descriptive Statistics | Scoring in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–6 | 7–10 | 11–15 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Advantageous Result | |

| Efficiency | 4 | 15 | 12.37 | 2.74 | 7.50% | 2.50% | 90.00% |

| Creativity | 3 | 15 | 11.10 | 3.18 | 12.50% | 17.50% | 70.00% |

| Satisfaction | Descriptive Statistics | Scoring in the Questionnaire | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9–20 | 21–32 | 33–45 | |||||

| Min | Max | Average | Standard Deviation | Unfavorable Result | Average Result | Advantageous Result | |

| Internal | 5 | 20 | 14 | 4.22 | 32.50% | 52.50% | 15.00% |

| External | 4 | 17 | 10.73 | 3.03 | 20.00% | 65.00% | 15.00% |

| General | 9 | 36 | 24.73 | 6.25 | 25.00% | 70.00% | 5.00% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tutak, M.; Brodny, J.; Dobrowolska, M. Assessment of Work Conditions in a Production Enterprise—A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135390

Tutak M, Brodny J, Dobrowolska M. Assessment of Work Conditions in a Production Enterprise—A Case Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135390

Chicago/Turabian StyleTutak, Magdalena, Jarosław Brodny, and Małgorzata Dobrowolska. 2020. "Assessment of Work Conditions in a Production Enterprise—A Case Study" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135390

APA StyleTutak, M., Brodny, J., & Dobrowolska, M. (2020). Assessment of Work Conditions in a Production Enterprise—A Case Study. Sustainability, 12(13), 5390. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135390