The Role of Social Farming in the Socio-Economic Development of Highly Marginal Regions: An Investigation in Calabria

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Socio-employment integration of disadvantaged workers and people

- Social services and activities for local communities

- Services in support of medical, psychological, and rehabilitation therapies, including using farm animals and growing plants

- Projects aimed at: safeguarding biodiversity, fostering environmental and food education and making the area known by organising social and educational farms

2. Social Farming in Disadvantaged Regions: Elements from the Literature

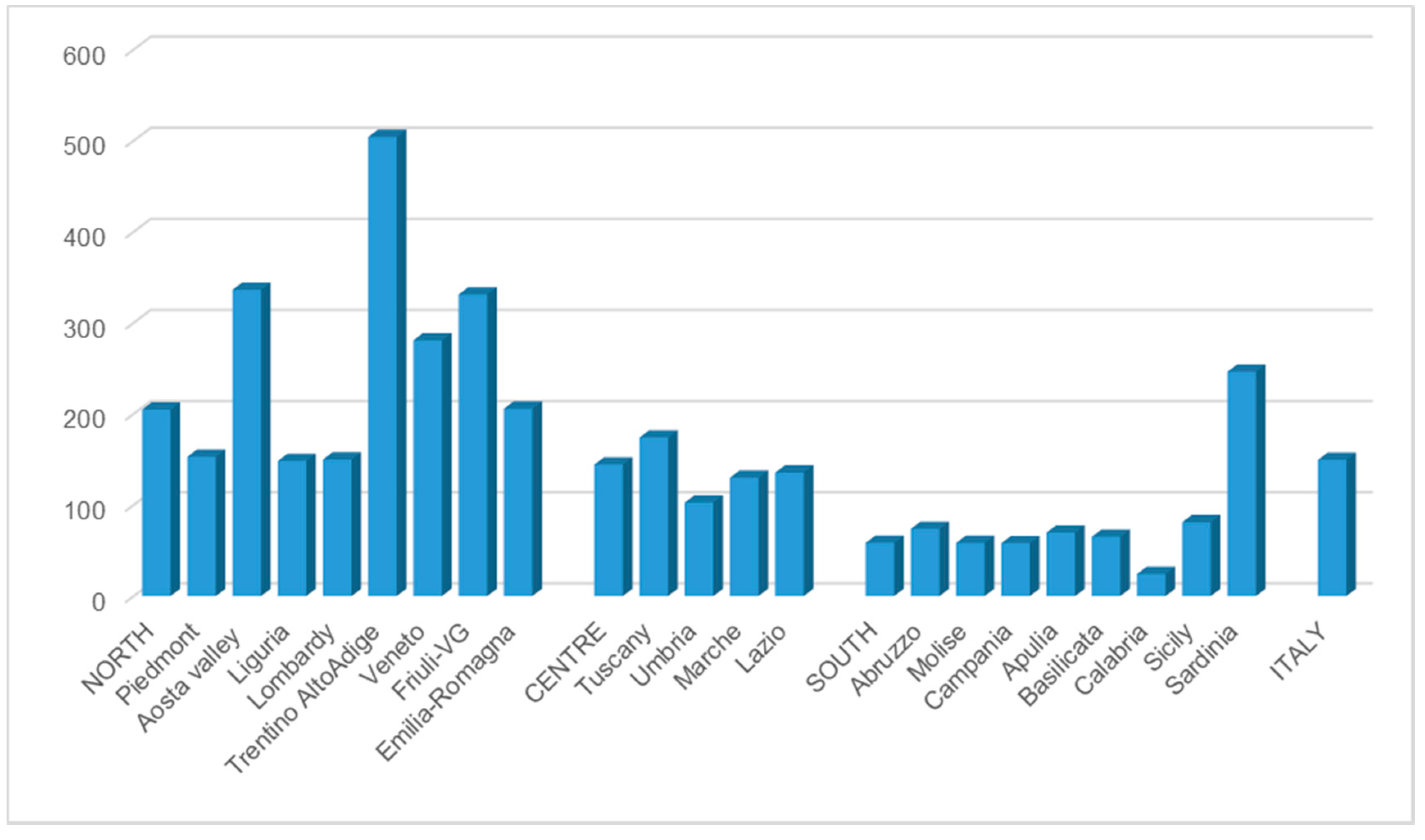

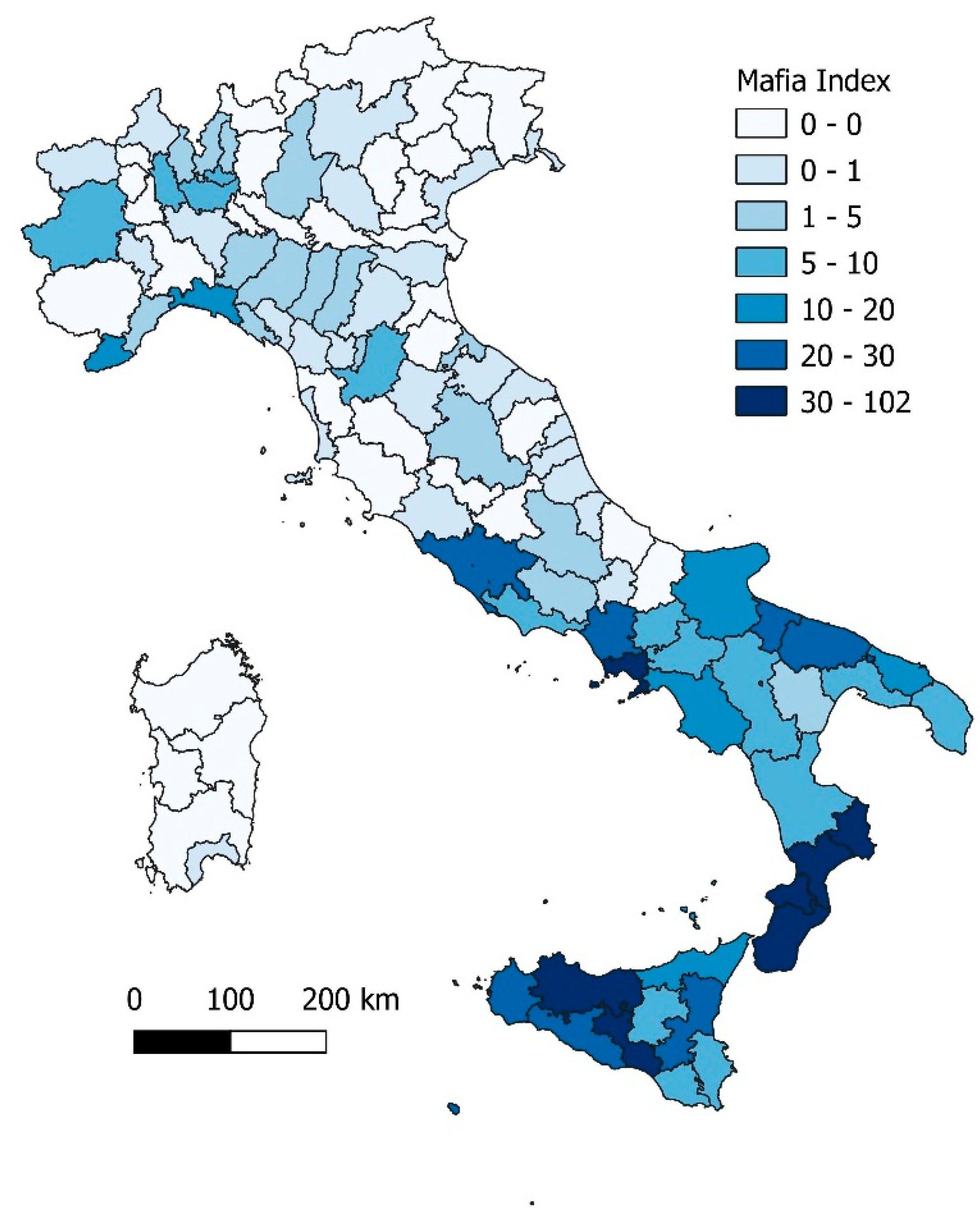

3. The Case Study Area: Calabria, a Lagging Region in Southern Italy

4. Methodological Approach to the Field Investigation: Direct Interviews and Thematic Analysis

5. Results of the Investigation in Calabria

5.1. The Set of Social Farms: Basic Characteristics

5.2. The Economic Mission: Competitive and Growing Social Farms, Part of Innovative Networks

‘When we started, in this field there was nothing, there was much improvisation ... tabula rasa ...’

5.3. The Social Mission: Activities and Services for the Local Community

‘The aim of our cooperative is the integration into its work of disadvantaged people like abused women, etc. ... But over time B has realised that this type of activity lent itself well, became applicable, alternatively, to other groups of disadvantaged people, such as drug addicts, immigrants, etc. … therefore, an involvement of other groups in social farming activities is underway.‘

‘We do projects, for example, with schools and kindergarten. The school contacts us, to do pet therapy, hippo-therapy, and we prepare a program .... There is, for example, the case of a school in Gioiosa Jonica, which every 15 days brings 70 disabled children for pet-therapy and hippo-therapy … ’

‘Social farming, in its most multifunctional meaning, lends itself well to combining welfare and environmental sustainability ... think, for example, of the discourse on the impoverished public domain, full of abandoned land ... there are many issues that we are trying to link up, also together with A …’

‘The schools located in this area have all come to us ... Initially, we were going around to present our services, to explain what is a social farm ... now they look for us ...’ ‘At the beginning, the main problem to face was the complete lack of knowledge of these structures, the social farms, their pedagogical work, etc. At that time schools were very rigid, they did not easily modify their programmes in order to accept our proposals ... now they seem to be more open to services like ours ... many schools work independently ... some schools have to follow an internal program, and in others the teachers have the possibility to choose ... compared with the past, there is now more direct contact with teachers ... there has been an awareness, that is, a cultural evolution in the local schools…’

5.4. Threats and Opportunities for Accomplishing the Mission of Calabrian Social Farms: Three Critical Issues

5.4.1. Much Too Peripheral: The Geographical, Economic, and Institutional Isolation

‘We work in a sort of desert, because there are no synergies, no network, and no integration …’

‘They never listened to us during the planning phase of the measures and the actions …’

‘… the role of the regional government is not adequate, and regional funding, on the basis of the legislation in force, is not timely. Moreover, even the definition of the policy guidelines for social farming and social services is not adequate. If the support was adjusted to the actual needs of the cooperatives, our social services could be quintupled…’

‘….. that of the Piana di Gioia Tauro, a context with a great specialisation in olive and citrus cultivation (in particular the clementines are a product of excellence)… However, this district has not been able to create, over time and durably, synergies, networks and organisations capable of effectively engaging in the promotion and enhancement of the typical agro-food products and the landscape of olive and citrus fruits. Therefore, the competitive level of the local district/supply chain is low, despite its potential …’

5.4.2. What Kind of People Are Needed for Growing and Expanding: Professional Workers or Volunteers?

‘The two people in charge of our association and of its activities (the President, and her husband) are respectively an engineer and a veterinarian, while the collaborating volunteers are all women, graduates (an accountant, a graduate in forestry sciences, a pedagogist, etc.), coming from the province of Reggio…’

‘….. And we had this problem, for example, when we had to close the balance sheets, always at a loss! There was an evident difficulty in terms of the financial sustainability of our activity, so we had difficulty with the payments of many workers.... So many delays in payments ... So, we said: The cooperative must help disadvantaged people, must give them dignity, but it must also stand on its own feet! We have to recruit an adequate number of managerial staff to improve … ’

‘One of our dilemmas is: How to grow up, without losing the ethical dimension, towards legality?’

‘…. to avoid an excess of professionalisation, and therefore to prevent the risk of the separation of the cooperative from the context in which it performs its social function …’

5.4.3. The Most Critical and Serious Question: The Presence of the Mafia

‘Now, with the expansion of our activity, we risk meeting new ‘problems’ ... the last incident happened in October, they broke through the roof, and they stole some machines and some tools. As far as other episodes are concerned (fire, devastation of the land), from the investigations, it is clear that they were caused by the Mafia organisations…’

‘Mobsters went to our employees who were working on our land that was confiscated [from the Mafia], and which was granted to us, and they told them that, if they did not leave the land by the end of the day, they would kill them…”

‘This is also why we are in the sights of the ‘ndrangheta ... because we grew up ... everything started with the confiscated property, the building where the local Mafia clan lived. We are an organisation that gives more and more work, and this bothers them … ‘

‘the founders of A were, alone, at the forefront in the resistance to the Mafia, but today even those who initially were scared are getting closer and closer to us…‘

‘Before our initiative, most of the farms could not survive the attacks and the pressure of the Mafia, but nowadays we pay 40 cents per kilo for their oranges, and this definitely helps them to resist and survive … ‘

‘Ethics is not only right, but also profitable …’

‘This is a basic aspect of our identity, of our mission in this place: Getting in contact, connecting, with cooperatives and firms attached by the ‘ndrangheta, and supporting them in their reaction and resistance to its pressure …’

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Iacovo, F. La responsabilità sociale dell’impresa agricola. Agriregionieuropa 2007, 8. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/8/la-responsabilita-sociale-dellimpresa-agricola (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Giarè, F.; Borsotto, P.; De Vivo, C.; Gaito, M.; Pavoncello, D.; Innamorati, A. Rapporto Sull’agricoltura Sociale in Italia. Ministero Delle Politiche Agricole Alimentari e Forestali; Rete Rurale Nazionale: Rome, Italy, 2017; Available online: https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/18108 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C.; Abbate, T.; Dimitrova, V. Agriculture and the social farm: Expression of the multifunctional model of agriculture as a solution to the economic crisis in rural areas. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- Hassink, J.; Grin, J.; Hulsink, W. Multifunctional Agriculture Meets Health Care: Applying the Multi-Level Transition Sciences Perspective to Care Farming in the Netherlands. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Groot, J.C.J.; Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D.; Stobbelaar, D.; Van Ittersum, M.K. Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90 (Suppl. 2), S112–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Technical Workshop: The Implications of Social Farming for Rural Poverty Reduction, 15 December 2014. Final Report. 2015. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5148e.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- European Economic and Social Committee Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on ‘Social Farming: Green Care and Social and Health Policies’ (Own-Initiative Opinion) (2013/C 44/07). Official Journal of the European Union, C44/44-48, 15.2.2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012IE1236&from=IT (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- D’Angelo, D. Un Quadro Sull’agricoltura Sociale in Italia, Tra Presente e Futuro. Agriregionieuropa 2017, 50. Available online: https://agriregionieuropa.univpm.it/it/content/article/31/50/un-quadro-sullagricoltura-sociale-italia-tra-presente-e-futuro (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Becchetti, L.; Cermelli, M. Civil economy: Definition and strategies for sustainable well-living. Int. Rev. Econ. 2018, 65, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iacovo, F.; O’Connor, D. Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe: Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; ARSIA, Agenzia Regionale per lo Sviluppo e l’Innovazione nel settore Agricolo-forestale: Firenze, Italy, 2009; SoFar project: Supporting EU Agricultural Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Moruzzo, R.; Rossignoli, C.M. Collaboration, knowledge and innovation toward a welfare society: The case of the Board of Social Farming in Valdera (Tuscany), Italy. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2017, 23, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganò, F.; Musolino, D. Agricoltura Sociale Come Politica di Sviluppo per le Aree Svantaggiate. Il Caso del Mezzogiorno. In Dimensionen Sozialer Landwirtschaft—Dimensione dell‘ Agricoltura Sociale; Elsen, S., Zerbe, S., Eds.; bu, press: Forthcoming, Bolzano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Petrics, H.; Rossignoli, C. Social Farming and social protection in developing countries in the perspective of sustainable rural development. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on ‘Agriculture in an Urbanizing Society. Reconnecting Agriculture and Food Chains to Societal Needs’, Rome, Italy, 15–17 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, D.; Crea, V.; Marcianò, C. Being Excellent Entrepreneurs in Highly Marginal Areas: The Case of the Agri-Food Sector in the Province of Reggio Calabria. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svimez. Rapporto Svimez 2017 sull’economia del Mezzogiorno; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dessein, J. A Critical Reading from Cases and Emerging Issues. In Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe: Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; Di Iacovo, F., O’Connor, D., Eds.; ARSIA, Agenzia Regionale per lo Sviluppo e l’Innovazione nel settore Agricolo-forestale: Firenze, Italy, 2009; SoFar project: Supporting EU Agricultural Policies. [Google Scholar]

- Giarè, F.; Ricciardi, G.; Borsotto, P. Migrants Workers and Processes of Social Inclusion in Italy: The Possibilities Offered by Social Farming. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREA, Fotografia dell’Agricoltura Sociale in Italia. 2018. Available online: https://rica.crea.gov.it/APP/agricoltura_sociale/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Rete Rurale Nazionale 2014–2020, Bioreport 2017–2018. L’agricoltura Biologica in Italia, Roma. 2019. Available online: http://www.sinab.it/sites/default/files/share/bioreport_2017_2018defWEB.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Cannari, L.; Franco, D. Il Mezzogiorno: Ritardi, qualità dei servizi pubblici, politiche. Stato e mercato 2011, 91, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, D. The north-south divide in Italy: Reality or perception? Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2018, 25, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svimez. 150 Anni di Statistiche Italiane Nord. e Sud 1961–2011; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi, G. Ricchezza e Povertà. Il Benessere Degli Italiani, dall’Unità ad Oggi; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolleb, E.; Wolleb, G. Divari Regionali e Dualismo Economico; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Conti Economici Territoriali. Anno 2017; Statistiche Report; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. La Spesa dei Comuni per i Servizi Sociali; Statistiche Report; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. La Povertà in Italia. Anno 2017; Statistiche Report; Istat: Rome, Italy, 26 Giugno 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nifo, A.; Vecchione, G. Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 1628–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, D. Characteristics and effects of twin cities integration: The case of Reggio Calabria and Messina, ‘walled cities’ in Southern Italy. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2018, 10, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, D. (Ed.) The Contribution of Infrastructure to Regional Development, Commission of the European Communities; Infrastructure Study Group: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, G.; Vitetta, A. Short-term forecasting in road evacuation: Calibration of a travel time function. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2011, 116, 615–626. [Google Scholar]

- S&W Spiekermann & Wegener, Urban and Regional Research (2014) ESPON MATRICES Final Report. Available online: https://www.espon.eu (accessed on 20 May 2014).

- Svimez. Rapporto Svimez 2013 sull’economia del Mezzogiorno; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alampi, D.; Iuzzolino, G.; Lozzi, M.; Schiavone, A. La Sanità. In Il Mezzogiorno e la Politica Economica dell’Italia. Workshops and Conferences, Numero 4; Cannari, L., Franco, D., Eds.; Banca d’Italia: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, R.; Mantuano, M. L’ attrazione di investimenti diretti esteri in Italia e nel Mezzogiorno: Il ruolo delle politiche nazionali e regionali. L’industria 2011, 29, 623–642. [Google Scholar]

- Daniele, V.; Marani, U. Organised crime, the quality of local institutions and FDI in Italy: A panel data analysis. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2011, 27, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direzione Nazionale Antimafia. Relazione Annuale Sulle attività Svolte dal Procuratore Nazionale Antimafia e Dalla Direzione Nazionale Antimafia Nonché Sulle Dinamiche e Strategie Della Criminalità Organizzata di tipo Mafioso nel Periodo 1° Luglio 2013—30 Giugno 2014. Gennaio 2015. Available online: https://www.camera.it/temiap/2015/03/04/OCD177-1033.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Asmundo, A.; Lisciandra, M. The Cost of Protection Racket in Sicily. Glob. Crime 2008, 9, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asso, P.F.; Trigilia, C. Mafie ed Economie Locali. Obiettivi, Risultati e Interrogativi di una Ricerca. In Alleanze nell’ombra. Mafie ed Economie Locali in Sicilia e nel Mezzogiorno; Sciarrone, R., Ed.; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccorsi di Patti, E. Weak Institutions and Credit Availability: The Impact of Crime on Bank Loans. In Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers); Banca d’Italia: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ciconte, E. ‘Ndrangheta dall’unità a Oggi; Roma-Bari: Laterza Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gambino, S. La Mafia in Calabria; Città del Sole Edizioni: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, G. Inchiesta Parlamentare sulle Condizioni dei Contadini Nelle Provincie Meridionali e nella Sicilia; Volume VI—Sicilia. Tomo I; Tipografia Nazionale Bertero: Roma, Italy, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Mack Smith, D. A History of Sicily: Modern Sicily; Chatto and Windus: London, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Transcrime. Dove operano le mafie in Italia. In: Progetto PON Sicurezza 2007–2013. Gli investimenti delle mafie. 2013. Available online: http://www.transcrime.it/pubblicazioni/progetto-pon-sicurezza-2007-2013/ (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Gambetta, D. The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, G.; Lo Forte, G. Lo Stato illegale. Mafia e politica da Portella della Ginestra a oggi; Roma-Bari: Laterza, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Snowball Subject Recruitment; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.A. Comment: On Respondent-Driven Sampling and Snowball Sampling in Hard-to-Reach Populations and Snowball Sampling Not in Hard-to-Reach Populations. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, P. La Ricerca Sociale: Metodologia e Tecniche. Vol. 3: Le Tecniche Qualitative; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; Cassell, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2004; pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, L.; Egan, M.; O’Connell, N. The Experience of Unemployment in Ireland: A Thematic Analysis; UCD Geary Institute Discussion Paper Series; University College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, C.; Willmott, J. The thief of womanhood: Women’s experience of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.J.; Kitzinger, C. Denying equality: An analysis of arguments against lowering the age of consent for sex between men. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, D. The mental maps of Italian entrepreneurs: A quali-quantitative approach. J. Cult. Geogr. 2018, 35, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golijan, J.; Dimitrijević, B. Global organic food market. Acta Agric. Serbica 2018, 23, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismea and Svimez. Rapporto sull’agricoltura del Mezzogiorno; Ismea and Svimez: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeAttachment.php/L/IT/D/1%252F0%252F0%252FD.6592694c7471bb7c8c31/P/BLOB%3AID%3D10029/E/pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Ikinci, A.; Bolat, I.; Şimşek, M. International Pomegranate Trade and Pomegranate Standard; Presented at the International Gap Agriculture & Livestock Congress: Şanlurfa, Turkey, 25–27 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, N.; Jamwal, V.L.; Shukla, M.; Gandhi, S. The Rise of Nutraceuticals: Overview and Future. In Biotechnology Business—Concept to Delivery; Saxena, A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY USA, 2020; pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni; R. La teoria dello Sviluppo Regionale; CUSL Nuova Vita: Padova, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R. Regional Economics, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New, York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. I Distretti Industriali 2011. 9° Censimento dell’Industria e dei Servizi e Censimento Delle Istituzioni non Profit, 2015; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.; Berruti, G. Social Agriculture, Antimafia and Beyond: Toward a Value Chain Analysis of Italian Food. Antropol. Food. 2019. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/aof/10306 (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Campiglio, L. Le Relazioni di Fiducia nel Mercato e Nello Stato. In Mercati Illegali e Mafie L’economia del Crimine Organizzato; Zamagni, S., Ed.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzino, P. La mafia siciliana come “industria della violenza”. Caratteri storici ed elementi di continuità. Dei Delitti e delle Pene 1993, 2, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarrone, R. Il capitale sociale della mafia. Relazioni esterne e controllo del territorio. Quaderni di Sociologia 1998, 18, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santino, U. Fighting the Mafia and Organized Crime: Italy and Europe. In Crime and Law Enforcement in the Global Village; McDonald, W.F., Ed.; Anderson Publishing Co.: Cincinnati, H, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mori Sì, la mafia ha perso. Il Foglio, 30 Maggio 2017. Available online: https://www.ilfoglio.it/giustizia/2017/05/30/news/mafia-ha-perso-falcone-borsellino-137080/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Multifunctionality and Value Creation in Rural Areas of Southern Italy”. In Proceedings of the 118th Seminar of the EAAE ‘Rural development: Governance, policy design and delivery’, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 25–27 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Verso un nuovo paradigma per la creazione di valore nell’impresa agricola multifunzionale. Il caso della filiera zootecnica. Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Value portfolio in the multifunctional farm: New theoretical-methodological approaches. Rivista di Econ. Agrar. 2012, 2, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Padovani, R.; Provenzano, G. La Convergenza Interrotta”. Il Mezzogiorno del 1951–1992: Dinamiche, Trasformazioni, Politiche. In La dinamica Economica del Mezzogiorno; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Servidio, G. Industria Meridionale e Politiche di Incentivazione: Storia di un Progressivo Disimpegno. In La Dinamica Economica del Mezzogiorno; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marcianò, C.; Palladino, M. La Pianificazione Integrata in Un’area Calabrese Nell’ottica di una Rete di Affiliazione. Analisi Delle Strutture dei Partenariati Locali e del Loro Sviluppo. In Governance rurali in Calabria; Marcianò, C., Ed.; Università degli Studi Mediterranea: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2013; pp. 337–402. [Google Scholar]

- Marcianò, C.; Romeo, G. Integrated Local Development in Coastal Areas: The Case of the “Stretto” Coast FLAG in Southern Italy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social Farm | Location (Province) | Legal Form | Foundation Year | Size * | Turnover (Euro) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Reggio C. | Group of cooperatives, firms, associations | 2003 | Big | More than 1mln |

| B | Catanzaro | Group of cooperatives and associations | 1976 | Big | 500k−1mln |

| C | Reggio C. | Cooperative | 2004 | Medium | 100k−500k |

| D | Reggio C. | Cooperative | 2010 | Small | 100k−500k |

| E | Reggio C. | Association | 2008 | Small | 100k−500k |

| F | Cosenza | Cooperative | 1995 | Small | Less than 100k |

| G | Catanzaro | Cooperative | 2008 | Small | Less than 100k |

| H | Cosenza | Cooperative | 1982 | Small | Less than 100k |

| I | Catanzaro | Cooperative | 1995 | Small | Less than 100k |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musolino, D.; Distaso, A.; Marcianò, C. The Role of Social Farming in the Socio-Economic Development of Highly Marginal Regions: An Investigation in Calabria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135285

Musolino D, Distaso A, Marcianò C. The Role of Social Farming in the Socio-Economic Development of Highly Marginal Regions: An Investigation in Calabria. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135285

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusolino, Dario, Alba Distaso, and Claudio Marcianò. 2020. "The Role of Social Farming in the Socio-Economic Development of Highly Marginal Regions: An Investigation in Calabria" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135285

APA StyleMusolino, D., Distaso, A., & Marcianò, C. (2020). The Role of Social Farming in the Socio-Economic Development of Highly Marginal Regions: An Investigation in Calabria. Sustainability, 12(13), 5285. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135285