Abstract

The organization of multifunctional agriculture for the provision of social/health/educational services is spreading throughout Europe and elsewhere. This concept is not new, and the organization of practices differs according to each country’s welfare model. The aim of this paper is to reflect on the existing practices and trends and to provide a suitable comprehensive framework. Starting from long-term research action on this topic started in 1999 and from participation in European research projects and networks, this paper reflects on the features of existing practices and distinguishes emerging social farming models. Specific attention is given to the potential of social farming for both global change and the re-organization of local societies and welfare organizations. The diverse social farming models and their interactions with emerging constraints and needs during times of challenge and crisis, such as those we are currently experiencing, are considered in order to understand their basic principles (from direct support to co-production models), as well as how they correlate with the ongoing process of welfare reorganization and evolutionary societal demands.

1. Introduction

Social farming can be considered a retro-innovative [1] solution, where agricultural resources (plants and animals) are organized at the farm level and in informal environments to provide innovative social health services in both peri-urban and rural areas for diverse people in need [2].

In scientific debates, as well as in the current practices and policies of many European countries, attention is given to social farming as part of the intersection between the diverse reflections arising in agricultural- and socioeconomic-related sciences, as well as those in the health and social sciences.

In agricultural- and socioeconomic-related sciences, attention is divided between perspectives of multifunctional agriculture [2,3,4] and the organization of ecosystem services [5] and nature-based solutions [6], as well as the outcome of on-farm diversification from agricultural activities, where farms try to overcome a decline in the economic value of food commodities produced with new diverse activities that are able to generate new sources of income [7].

In the social health sector, relevant debates concern, on the one hand, the opportunity to move from a paternalistic role of the state to a more responsible welfare society open to the contributions of many diverse stakeholders [8] and, on the other hand, the opportunity to adopt new tools and strategies that are able to increase the capabilities of disadvantaged people, as well as the organization of trajectories able to increase their opportunities for social justice [9].

In the crossroads of such discussions, and considering the perspectives and efforts of many diverse actors (social health workers, NGOs, farmers, citizens, policy makers, and consumers), many social farming projects and practices have emerged in Europe and elsewhere, with diverse organizational structures and outcomes [10]. Some of these practices are strongly embedded in defined welfare rules, while others are founded on active community participation. To some extent, currently existing self-help and mutually supportive social practices in traditional rural communities around the world make use of nature, agricultural resources, and rural household solutions, and can also be labeled under the contemporary social farming umbrella so as to be better recognized to reinforce existing social services in traditional rural communities [11].

During the last few years, a growing number of authors have illustrated emerging social farming features in diverse countries [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], as well as growing networks and platforms [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] and possible applications and related outcomes in social farming initiatives [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. In most cases, social farming practices are locally grounded and emerge according to specific cultural and regulatory scenarios, the most relevant being welfare system organization at the national level.

Starting in Europe (but present today in many countries (South Korea, Japan, etc.)), the debate on social farming focuses on common topics, such as the traditional scarcity of public funds and social services in both urban and rural areas; the demand for social support in rural societies to tackle urgent problems (e.g., aging, depopulation, and migratory in- and outflows); the growing debate at the national level on welfare reform, especially in Europe; the organization of innovative and more sustainable and equitable productive and reproductive systems in times of crisis; shocks and scarcities; and the opportunity to use more effective tools to increase the capabilities [42] of disadvantaged people, while also generating innovative services using nature-based solutions. Social farming has an impact on the participants involved but also on others. Among the potential outcomes, the following should be underlined: impacts involving local rural community organization, rural–urban bonds, ethical food content, social impacts, and social capital [10,43,44,45].

The aim of this paper is to reflect on the existing practices and trends and to provide a suitable comprehensive framework. Starting from this, we construct and highlight emerging social farming models. Specific attention is given to the potential of social farming during the present period of global change and in the reorganization of local societies and welfare organization. In times of crisis—from an economic point of view but mainly from societal and environmental points of view—a specific reflection must be made on diverse social farming models and their interactions with emerging constraints and needs to understand their basic principles (from direct support to co-production models), as well as how they can agree with the ongoing process of welfare reorganization and evolving societal demands.

2. Methodology

This paper reflects on the existing social farming practices in European and extra-European scenarios. The aim of this study is to stimulate attention given to this topic, as well as debates on existing models and their opportunities and limits, given the evolutionary and challenging contexts in which they are developing. To achieve this, the present article is based on different sources. The present author performed research on the topic starting in 1999 at a regional scale in Tuscany. He also coordinated from 2006 to 2009 the EU-SoFar project (founded by the VI-EU research framework) that, for the first time, investigated this peculiar aspect of multifunctional agriculture in six European countries (Italy, France, The Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, and Slovenia). The results from this project were presented at the congress organized by the EU Commission and the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor of Hungary on Combating Poverty and Social Exclusion in Rural Areas (Budapest, 11–12 June 2009). In the meantime, the author acted as a national delegate for the Cost Action 866 on Green Care, which included most EU countries, as well as some others in the pre-adhesion regime, and took part in the Farming for Health community of practices. The author also took part in meetings, congresses, and study-related visits on the topic in different EU (Belgium, Germany, Greece, Czech Republic, France, Slovakia, Spain, Italy, Norway, and The Netherlands) and non-EU countries (Japan and South Korea) and worked on the social farming topic with the FAO to explore this topic at a global scale. During most of this time, the research group at Pisa University has engaged in diverse research action projects in Tuscany (in the Lucca, Grosseto, and Pisa areas), Piedmont (in the Turin area in collaboration with a national farm association), and nationally (with the Coldiretti farm association). In Italy, the author accompanied the Ministry for Agriculture in the definition process for the national law on social farming (L.141/2015). In the frame of the third mission of the University, he contributed to the design and management of the Orti ETICI social farming project that has been working since 2009 at the Pisa University farm. This long-term research project informed the reflections presented in this paper, as well as the evidence and cases presented in Section 4.4 that were directly collected, or the result of, our research action projects. At the same time, diverse authors, with a focus on many specific countries, including rural sociologists and agricultural economists and geographers, analyzed this topic from diverse angles and perspectives. The growing number of articles and cases presented facilitated the collection of updated information and views that were particularly useful for reflection.

As noted, our reflections are grounded in large-scale research conducted in Europe and Italy with the involvement of many diverse local, regional, and national stakeholders, as well as in the analysis of existing literature and extra-EU practices and evidence. In our case, the researcher is indebted to the project holders on the ground [2,10,11,22,39,43,45,46,47].

The following sections are informed by the continuous process of triangulation between the information collected during our action research in the field, as well as by the interactions and analyses of emerging research from other authors.

In previous studies, different terms were used to present practices that have diverse relationships with nature, like social farming, social agriculture, care farming, and green care. As discussed in the next section, these terms are not always synonymous and are mainly linked to differences in existing practices but also to more extensive or specific uses of resources presented at the farm level. In our paper, we have chosen to use the term social farming because we focus mainly on the natural resources mobilized at the farm level. At the same time, one of the main conclusions of this article focuses on the possibility to generate a European web, where different practices, according to their limits, opportunities, and goals, might work together by clarifying their roles under the framework of diverse policies. Nevertheless, we continue to use the term “social farming” for the whole web of practices due to the fact that this term is widespread in Europe in different educational projects funded by the EU and seems to be one of the most recognized concepts, although we recognize that the possibility to use a broader term can only emerge from collaborative dialogue among researchers, practice-holders, and policy makers.

3. Social Farming in the Co-Evolution between Practices and Research

As indicated in [2], social farming has re-emerged since 2003 at the EU level in scientific and public debates under two main forces that are linked, on the one hand, to the demand and opportunities for new technical tools (e.g., nature-based solutions, horticultural therapy, and animal assisted intervention) to provide innovative services for diverse target groups and, on the other hand, to support better social protection nets in rural areas (in addition to peri-urban services) where it is increasingly difficult to ensure equivalent safety nets to those in an urban context.

At the European level, the organization of the Farming for health Community of Practice has generated diverse spin-offs like the SoFar project (2006–2009) and the Cost Action 866 on Green Care (2007–2010). The SoFar and Cost 866 activities also informed the CESE (European Economic and Social Committee) deliberations on social faming in Europe. Since then, many other Erasmus and Interreg projects [23,27,28,32,33] have focused on the social farming area of interests, although without specific research initiatives, instead being mainly focused on educational training and support activities.

It is worth recognizing that all research and learning projects were based on the experiences of pre-existing practices spread since the 1970s in Europe, which have subsequently been mainly active in the shadows [2,35]. Thanks to the active participation of these actors, there has been a strong and continuous evolution of practices on the ground that agree with the growing research activities on the topic. This match between practitioners and researchers started with national and EU research activities and networking initiatives, thereby stimulating deeper thinking along a process of continuous analysis and codification towards collective knowledge creation that has progressively affected larger societal strata [33,34]. The attention given to social farming practices can be divided into three different phases:

- The first stage (knowledge creation), where research activities and debates focused mainly on a deeper comprehension of the emerging topic. In this phase, researchers and private and public stakeholders were involved in a collective process to create and share their understanding and values [7] surrounding the social farming concept, as well as its features and possible facets. This collective knowledge process was mainly supported by participatory methods within European and national projects and activities and remains ongoing in specific research areas. The main evidence from this phase provided a better understanding of how the same resources (plants, animals, farms, and groups of people involved) in diverse Europeans legal frameworks and welfare systems were able to produce specific social farming (SF) practices with different outcomes [2,10]. During the first stage, diverse terms like green care (an umbrella term related to all the activities done in the green, in nature, with plants and animals), care farming (linked to on-farm diversification activities in the frame of the Northern European welfare model), and social farming (attached to the Mediterranean welfare systems and the active involvement of farmers inside a welfare mix of actors) emerged not as synonymous terms but rather as concepts attached to diverse meanings, principles, cultures, public systems, and common frames and perspectives [7,16,18,35,36]. For most of the actors involved, it was evident that social farming initiatives represented an emerging part of a larger iceberg, but, at the same time, it was also clear how rich in terms of innovative elements these initiatives were;

- In the second stage, starting from the emerging evidence, research focused on developing a better understanding of the specific situations in European countries [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,31], as well as in Asian contexts [21]. During this stage, educational and training projects, as well as national networking activities, spread this concept, albeit sometimes using different names with overlapping content and meanings [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. At the same time, especially where the topics had already been explored, an attempt was made to deeply codify transitional management processes, trans-disciplinary paths, evaluation methods, and evidence-based outcomes [16,45,46];

- In the third ongoing phase, increasing attention to the topic emerged in the political arena. This political interest was stimulated by emerging research evidence, as well as the organization of regional and national platforms involving local public and private stakeholders who were advocating for policy support and regulatory frameworks. In many countries, to develop diverse top-down or bottom-up paths, such interests were translated into policy actions under the definition of national regulatory frames, laws, plans, and policy supports. This phase remains ongoing according to diverse national situations [31].

The following three steps facilitate the understanding of the transition process of social farming on a progressively larger scale in diverse countries: (1) the movement from existing unknown innovative practices towards an initial understanding and process of knowledge creation; (2) a shift to a second level of deeper understanding; and (3) the development of policy involvement and design [10]. Besides diversity, social farming initiatives both inside and outside Europe always focus on common targets, goals, and expectations, albeit with diverse organizations from local practices.

Such diversity is not always immediately clear for those approaching the topic within specific contexts, thus generating disbelief and mismatches. To better clarify how and why diversity grows, starting from our reflections, in the next section we depict some of the possible influential elements.

4. Discussion and Results

Based on the methodology described in Section 2, in this section we organize our reflections on the different existing forms of the use of nature in social farming practices in the EU. We first analyze the existing practices considering the diverse existing welfare models in the EU. Adopted by themselves, these welfare models do not explain the differences that can be observed in the provision of social farming services among countries adopting a common welfare model. Consequently, we reflect on the additional elements linked to the differentiation of existing components to build a conceptual framework that can better support the comprehension and analysis of existing social farming initiatives. Starting from the conceptual model, some reflections are offered considering the basic principles that inform different social farming practices, along with their relative strengths and weaknesses. Initiatives based on the co-production paradigm are emerging in many local practices to solve the emerging challenges of both the economy and society. Building on the content presented in Section 4, some final reflections and hypotheses are offered in Section 5.

4.1. Social Farming: A Welfare Dependent Option

The frequent problem arising when local actors, at different institutional levels or as project holders, start to approach the social farming topic is how to define the meanings, visions, frames, expectations, and processes to make the concept more clear and effective according to the perspectives of the actors involved. There is always tension between the diverse actors involved, the path dependency of existing frames and routines, and the demand for innovation and radical thinking [35]. This tension can also generate conflicting positions in local areas and channels regarding the relevant concepts and practices along diverse perspectives and organizations. This is also why the same agricultural resources—plants, animals, rural spaces, natural cycles, and small groups of interpersonal interactions—are shaped differently by the actors involved in their use and definitions. Stakeholders struggle to conceive, perceive, and experience [47] their ideas inside diverse legal frameworks, starting from specific cultural, social, historical, economic, and administrative frames and within the specific welfare systems and related opportunities and constraints that they might generate.

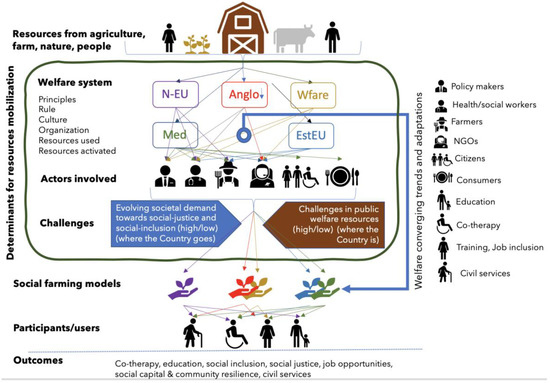

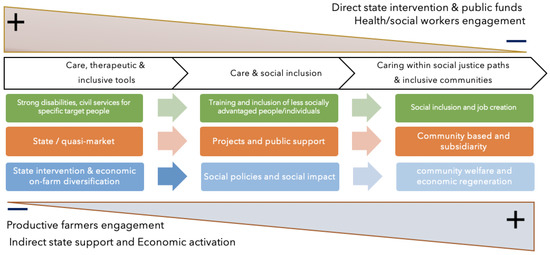

According to our research results and understanding, existing social farming across Europe (and elsewhere) is framed—among others—by diverse welfare models influencing the design, organization, and evolution of social farming practices, as indicated in Figure 1 and already stated in our previous work [2].

Figure 1.

Social farming: a conceptual framework to understand the processes of differentiation at the EU level (source: author).

Depending on the set of principles characterizing existing welfare models, resources from agriculture and nature are activated differently by the various actors formally recognized by existing rules. Besides this first framing element, local actors shape social farming initiatives by reading the emerging challenges (we will focus on this later) and trying to define possible answers using nature and agricultural farm processes. The actors involved, starting from their own understanding, knowledge, social background, cultural dimensions, visions, and expectations, design and manage a specific set of practices and achieve outcomes that can also differ depending of the ways the material and immaterial resources are activated by people/agriculture/nature.

In Europe, five well-known diverse welfare models have been codified [48,49,50,51] (Table 1). Social farming practices reflect the welfare systems where they are organized, as in the main element depicted below:

Table 1.

Social farming (SF) diversity in a European context (source: author).

- Northern European model: Here, the presence of strong state intervention driven by the public social health system gives relevance to social workers and their main goals in terms of innovative and quality-based service provisions. Resources from agriculture can be activated by involving diverse farmers in the public logic of intervention. In this situation, farms provide services according to public demands and the existing sets of rules that economically recognize farmers’ participation in the social protection network and their provision of services for selected targeted groups. Farmers diversifying their activity in social services always reduce their interest in agricultural economic processes that might then become residual. A driving motivation for the public social health sector is the implementation of innovative tools able to diversify the offers of social health services. On the other hand, from a farmer’s perspective, a driving motivation is the opportunity to have an income when the agricultural process itself no longer provides a sufficient income in times of market competition. In this case, a socio-therapeutic experience commonly emerges, and economic sustainability is mainly due to public support.

- Workfare: Where farmers are not recognized, the social sector can activate natural and agricultural resources under the financial support of public policies. This is always the case for countries like Germany and France, where mostly social workers are engaged in the organization of large- and medium-sized structures, strongly supported by the state. In such situations, the activation of agricultural economic activities plays an important role by involving disadvantaged people (potentially facing serious difficulties) in vocational training and motivating activities in a protected environment mainly supported by public policies.

- Anglo-Saxon: This charity system is based on foundations able to support social farming and garden initiatives that are normally driven by charity groups and NGOs. Similar to experiences based on workfare systems, Anglo-Saxon systems can use agriculture to support the daily life of disadvantaged people by aiding their agricultural processes only marginally based on their direct economic sustainability. In this case, socio-therapeutic and social inclusion experiences mainly emerge, as in the other practices illustrated above.

- Eastern European: Here, welfare is evolving far from soviet institutional intervention and is readapting into a European frame with local and regional authorities. In this case, social farming initiatives and their debates are beginning to emerge in regimes where communities still have a relevant role due to the involvement of pioneer projects rooted in the support of different actors. Ministries of agriculture are primarily supporting projects and social farming initiatives (in the Czech Republic, Poland, and partially in Hungary), as well as the ministries of labor and social affairs, labor offices (Czech Republic), and European Social Fund (ESF) projects. Agricultural products are a source of income that can be smaller (especially in therapeutic communities) or larger (in case of job inclusion) and also depend on the sizes of the farms involved. For foundations and foundation funds, small donors can support specific projects (especially in Hungary and Slovakia) [31].

- Mediterranean welfare: Social farming is organized among different stakeholders as the consequence of a welfare mix that includes (besides the public) the private specialized sector (the second sector), the so-called third sector (NGOs), families (the forth sector), and newcomers like responsible firms in agriculture (an emerging fifth sector). In this case, the provision of innovative services can be differently designed, becoming based more strongly on NGOs supported by public funding and/or farms operating at the community level. In the last case, recognition of farmers does not always come from direct public payments but is mainly activated by principles linked to the recognition of gifts and reciprocity in the community. In such practices, the participants involved are mainly those who need less attention and might be more easily involved in routine agricultural processes with specific support that are still manageable by the farmer.

- More recently, within the diverse welfare models, the role of the state has been complemented or substituted by private quasi-markets according to established public rules. In this case, families and users can directly buy social farming services provided by private firms in accordance with established guidelines provided normally by public institutions. This is the case for some specific co-therapeutic activities organized based on plants (horticultural therapy) and animals (animal-assisted activities) provided by both farmers and NGOs under state rules and directly funded by the users’ families. This is also the case for kindergartens organized by farmers or other emerging services under the same frame; in this case, agricultural resources are mainly used in a specialized way to provide innovative services for socio-therapeutic purposes or civil services.

From our direct experience, outside the EU, social farming initiative are growing differently in Japan and South Korea (where a recent national law was established supporting pilot initiatives) and in other countries (South and North America), which feature mostly isolated initiatives. In Japan, the organization of social farming initiatives is mainly linked to job inclusions connected with farmer cooperatives, while in the South Korean case, pilot initiatives are connected with small farms or community organizations and are mainly related to supporting the social inclusion of elders in traditional on-farm activities, as well as people with disabilities. Comprehension of social farming and welfare models is pivotal to facilitate a full understanding of the different relevant resource mobilization and organizational paths, especially for the countries and project holders that are coming into contact with the social farming concept but still need to determine how to introduce and promote the concept according to existing national welfare rules and systems.

4.2. Social Demands and Social Farming in a Challenging Scenario

As discussed in the previous section, welfare models matter in the organization of social farming initiatives, in the actors involved as project holders, in the relationships and responsibilities shared among public and private holders, and in the expected outcomes.

Besides the welfare models, other elements are also influential in the path design of social farming development. As shown in Table 2, the emergence and consolidation of social farming initiatives is country-dependent for specific challenging trends. These trends can be summarized based on at least two different driving forces:

Table 2.

Driving trends in social farming initiatives (source: author).

- The emerging challenges in terms of resources and adaptations that the welfare systems in Europe (and elsewhere) are facing; these challenges depend on the countries and their general macro-economic trends;

- The national societal demands in connection with the outcomes expected from social health services, which might catalyze diverse sensibilities in terms of social inclusion principles and perspectives. Both these forces have an influence on the organization of the diffusion and application of social farming initiatives at the national level, despite a common welfare model being in use in diverse situations.

For the first driving force (public resources and welfare), the debate inside and outside Europe—even before COVID-19—focused on the enormous challenges that many countries were facing in terms of public expenditures and service provisions in today’s changing society, especially challenges due to aging, progressive urbanization, migratory flows (in and out), pension scheme expenditures, economic automatization and job losses, climate change and emerging diseases, and technological health assessments [8,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. From this point of view, despite starting from diverse positions, most EU countries were already converging towards common trends, reflecting the role of the state in changing economic regimes and the design of the diverse participation of society in welfare provisions. In the meantime, the shift from a welfare state to social investment and the organization of a welfare society were considered as leverage to increase opportunities by giving more responsibility to community members in their everyday lives [59,60,61,62,63].

This approach has also received criticism among those arguing for the risk of public retirement as an outcome of a neoliberal regime where economic enterprises find justification to reduce their contributions to society that are ensured by the fiscal system. The emergence of COVID-19 will affect such discussions in connection with the expected economic crises in many countries, the increase in job losses, and also as a consequence of strong pro-active collaborative solutions activated in societies to overcome growing economic and social tensions. For many authors [64,65] and others in society, besides the dramatic impact of COVID-19, there is also the opportunity for reflection and change in terms of societal behavior, as well as the economic attitudes of firms. Sustainability, resilience to stresses, responsibility, and the collaboration of firms with society are some of the elements of this debate that apply to the same organization of public health social services, as well as the social farming topic, in different ways according to the diverse existing models. This topic is not new, and the transition from economic development to the concept of prosperity has been present in public debates for many years, where increasing attention has been given to collaborations between the economy, society, and nature in terms of the organization of affordable systems in times of scarcity and related enormous challenges [66]

The second driving force relates to the evolving expectations of social rights and how to best fit them. The debate initiated by Sen [42] around such capabilities influenced reflections on welfare provisions and social and individual dignity, thereby contributing to the concept of social justice. The influence of Sen, on the one hand, prompted debate over the fact that it is not important how and who is providing services but how an individual might have the rights to access such services, independent of the actors and resources involved. On the other hand, in the professional community, this discourse was translated into the provision of more personalized tools and paths able to fit and support people in need according to their individual expectations and, consequently, generate flexible contexts to a greater extent than universal support.

Social farming evolution can be observed in continuity with the main discussion summarized earlier. On the one hand, social farming evolution is related to the organization of more flexible and enabling contexts linked to the use of nature and agricultural-related processes and activities; on the other hand, from the perspective of social innovation [67,68,69,70], it re-embeds the rights and opportunities of disadvantaged people in the whole of society by organizing new public–private networks for the provision of potentially effective and more efficient services, both for different human targets and for diverse urban–rural areas.

In this way, the matrix that we present in Table 2 describes four possible situations that can emerge in different countries according to the level of the country’s perception and state-of-the-art of the driving trends. In case 1, which features sufficient public resources and a low level of expectations for the delivery of innovative services (also depending on a high level and quality of existing service provisions), social farming develops less—mainly in relation to a specific target of people or services (e.g., Denmark, Norway, Finland, and France). In other situations, despite the presence of strong challenges in terms of public funds (case 2) (e.g., Greece over the past few years and also Portugal), the organization of social farming initiatives remains limited to isolated cases in the presence of seemingly minor reactivity and innovation in public service provisions, at least for nature-based solutions. In other contexts, the demand for innovative services in the context of a low level of public resource scarcity (case 3) (like in the Netherlands, Germany at the very beginning of the 21st century, and some Eastern European countries that have experienced economic growth and the support of EU funds after their entrance into the EU) and in the context of the emerging need for welfare provisions (case 4) (e.g., Italy, but also Spain and eastern countries later on) have given more emphasis to social farming initiatives as a suitable solution to fit growing economic and societal needs. Where the “country is” depends on the overlap of historically rooted social, cultural, and economic elements and trends that inform the existing organization of practices on the ground. They always generate path dependency in everyday life, as well as constraints to possible innovations. On the other hand, where the “country goes” is always related to the presence of a facilitating context able to support social innovation processes and the pro-active behavior of visionary actors (public or private) who engage themselves in participatory multi-actor processes able to mobilize local resources in the frame of new perspectives. Such processes have been already investigated in social farming with specific reference to the situation in the Netherlands [16] and in Italy [45] and are related to transitional processes able to generate changes in attitudes, knowledge, and rules for contrasting scenarios.

4.3. Social Farming as a Conceptual Framework

Building on the elements drafted above, in this section, by elaborating on our research and knowledge, we conceptualize how social farming initiatives can be shaped differently in various European contexts.

Figure 1 shows the diversity of growth in social farming initiatives. Different social farming models always start from the same farming resources and often address common users but are activated by different determinants. These determinants are:

- Welfare models, which frame (with their institutional rules, cultural meanings, procedures, types of incentives, evidence, and practices) the landscapes in which social farming initiatives are established;

- Actors involved in the organization and evolution of the social farming sector are diverse, including public health–social–agriculture–rural technicians, the diversification of on-farm activities (in the northern European system), politicians, project holders (public, private, and third sector), users, and the association of users. Indirectly, citizens and food consumers can also be considered depending on the situation;

- How the driving trends are perceived by the actors that are activated by the welfare models;

- How active the local actors are and how accommodating the local environment is to innovation;

- What the relationships are between innovators and actors embedded in the existing regime and in what ways their relationships are able to facilitate innovation processes and mobilize resources from agriculture to provide innovative services.

Social farming initiatives are mainly organized according to the previous points, the targets addressed, and the outcomes expected. Each welfare model incorporates specific principles that are able to differently activate natural and agricultural resources (Table 3), such as direct public payments (state intervention), charity donations (based on voluntary funds for subsides by public resources), project activation (traditionally based on public, national, and/or EU funds), private quasi-market recognition (based on direct payments from families under the regulatory systems designed by public institutions), community-based initiatives (the latter being based on a mix of voluntary action, indirect recognition from citizens and consumers aiming to act ethically, and the choice of food from farmers willing to support the social farming initiative community on a voluntary basis, albeit within a public frame and with some support).

Table 3.

Principles for farm activation and the actors involved (source: author).

Existing welfare models and rules select and recognize diverse actors in the design and management of social farming initiatives. Not necessarily all the actors are equally recognized or involved in any country situation or welfare model. Conversely, diverse principles normally activate some of these actors in the design and management of social farming practices.

According to the mixture of welfare models and perspectives focused on by the stakeholders involved, as well as their positions and (un)satisfactory starting situations, the actors embedded in diverse environments can be differently engaged to analyze their reality, act to build coherent and new answers to emerging needs, and mobilize existing resources according to social innovation models. At the same time, efforts are commonly channeled along diverse goals and outcomes in connection with the main principles conditioning existing welfare models. Thus, different actors—always with strong ethical motivations—support specific goals in line with their visions, competences (in agriculture and in the social health sector), attitudes, and recognized priorities.

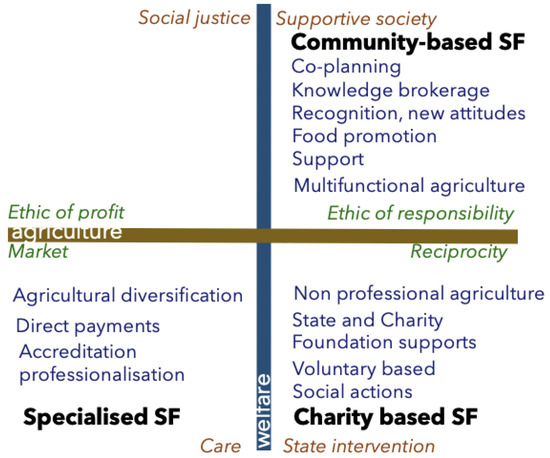

As illustrated in Figure 2, from an agricultural perspective, many farming styles can be adopted:

Figure 2.

Social farming models across Europe: principles, actors, and resource activation (source: author).

- Styles that are more oriented toward an ethic of profit (strongly embedded in a state–market divide perspective);

- Those according to common ideas developed within local actors; they might also follow an ethic of responsibility and reciprocity (this is more evident in places where the welfare principle allows a larger perspective of mutual collaboration among the actors involved. Moreover, the demand for innovative solutions is higher due to the driving trends connected to funding availability and societal demands involving relationships within society).

In the social health sector, the main perspectives of relevant social workers (public, private, or third sector) can be defined as follows:

- The idea of care and state intervention (again, mainly based on the perspective of strong state intervention);

- The perspective of social justice and the organization of a more supportive society by organizing the involvement of local communities (in a society, new perspective are focusing on the design of innovative solutions that consider participant rights and the relationships inside that society).

Figure 2 suggests at least three diverse solutions:

- A Specialized social farming model mainly based on direct public payments, with agricultural diversification still based on an ethic of profit, as well as specialization and accreditation of the farms involved in the new area of social services. In this model, attention is focused on the quality of the services provided to participants who can choose specific services over others. For social farming service providers, their activities move from the food/agricultural market to the market of services for the people. These services are provided under direct state payments and control. Participants are considered to be clients, and agricultural resources are a tool that can be usefully implemented in the social health sector under specialized competences. These solutions are mainly evident in the Northern European welfare models; they are strongly dependent on public funds and are able to activate specialized forms of horticultural-therapy and animal-assisted activity services devoted to caring activities.

- A Charity/project based social farming model, where the efforts of the public or third sector are still embedded in state intervention (funding and projects). Here, there is a prevalent ethic of responsibility and reciprocity among the actors involved, farmers are not directly involved in social farming, and the agricultural processes are run more in a relationship with caring activities that for their own sustainability. Such solutions are mainly developed in the Anglo-Saxon and in workfare welfare models but are also present in the Mediterranean system and in Eastern European countries for projects that contain some productive agricultural elements that involve active, at work, and disadvantaged people (although this model is strongly dependent on external funding under the organization of specific projects and supports);

- Community based social farming, where farmers are actively involved in local new networks where public and third sector social workers are also active. Farmers act on a voluntary basis, with little to no direct economic recognition. Direct state intervention is very limited due to funding scarcity. Agricultural processes are mainly run professionally, as economic sustainability still depends on them. Collaborative nets are organized, and the local society and consumers actively reshape their relationships, placing more emphasis on ethical food [71,72] and acting reciprocally with local farmers (e.g., using gifts) to facilitate the involvement of disadvantaged members of society. On a voluntary basis, farmers provide new opportunities to disadvantaged people by including them in everyday agricultural processes. Farming activities—agricultural as well as animal husbandry—remain food-business oriented but also support social opportunities for the participants involved. In this case, agricultural resources are mainly valorized for social health uses by strengthening their multifunctional aspects and the co-production of food and social services at the same time. Farmers work in collaboration with the social health sector (the public or third sector) and, in the meantime, gain evidence and recognition in the local society and by consumers. In this model, consumers are willing to recognize social farmers’ roles in society and pay new attention to the food they produce. These solutions are mainly developing in Mediterranean countries but, due to growing economic constraints, are also growing in Northern European countries, as well as in Eastern European countries.

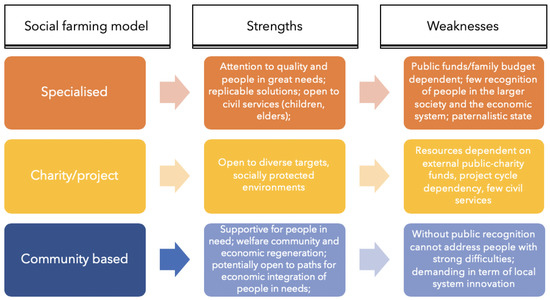

These three social farming solutions illustrate the diversity and meanings that inform social farming practices, at least in the EU. Each model presents its own strengths and weaknesses in the outcomes for the people involved and in local societal organization and future sustainability (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Social farming models’ strengths and weaknesses (source: author).

- The Specialized model (supported by state policies or direct family payments and a quasi-market) always defines quality and structured services that are able to support the lives of people in need and design innovative specialized services (e.g., AAA (Animal Assisted Activities) and also services for children and elders).

- The Charity model is still supported with public funds and/or charity support from the communities; it primarily involves social health and public/NGO actors and facilitates training and social inclusion mainly via agricultural processes and job support, and might generate a social impact on society.

- The Community-based model starts from a novel recognition of the diverse actors embedded in local society and the possibility for them to interact at different levels. The values that are needed in the community (economic, social, and environmental values) do not arise from specialized work divisions but instead from the reorganization of community coalitions among diverse stakeholders aiming at the design of more resilient and future-proof values. From this point of view, state and third sector interventions are complemented by private enterprise engagement but from the perspective of voluntary support (gifts) that are indirectly recognized by society (reciprocity). Subsidiarity, co-production, and civic economy are the emerging principles in this model.

4.4. Redesigning Services and Value Creation in Social Farming

Social farming initiatives can be analyzed from different perspectives related to their organization and diversity, their expected outcomes for users, the effectiveness of public funds, the evolutionary process of innovation in society, and the motivations and main competences involved. In parallel, all the mentioned aspects should be read in light of the specific social farming models adopted. Besides analysis of the current state-of-the-art, social faming could be analyzed in terms of future perspectives, especially under a scenario of the emerging societal challenges, to better understand what components of social farming practices (and in which direction) would best fit future needs. This will be the focus of our reflections in this section.

One key to moving forward from the latter perspective is related to the coherence among diverse social farming models with the welfare debates at the EU and non-EU levels. The other key looks to the possible existing links between social farming initiatives and SDG achievements. Regarding the first point, every day the demand for a transition from the strictly economic perspective that is still driving western societies to a reorganization of all societal, environmental, and economic factors is becoming more evident.

For the other factors, in 2009, Jackson introduced a semantic passage from “economic growth” to “prosperity”. The latter considers environmental limits, the need for (green) growth that is able to incorporate sustainability, and a shift in societal priorities and human habits, including consumerism. From a societal point of view, the One Health and One Wellness concepts connect human quality of life not only with economic power but also with the quality of environmental (water, air, and land) and human resources. More recently, Raworth [73] designed a doughnut metaphor to explain how our living space is compressed between a collapsing roof (represented by our primary challenges) and an elevating floor representing the reduction in the achievement of basic human rights due to increasing economic disparity and state intervention reductions in times of financial crisis. The expanding living space suggests a reduction in environmental pressures (also from the perspective of a One Health/One Wellness view) and a modification of the productive and redistributive mechanisms in society, which have been, to date, regulated by the fiscal leverage of a growing economy and the resulting state intervention. The globalized economic regime, on the one hand, has moved economic activities on a geographical scale; on the other hand, it has disconnected economies from territories and—by way of growing fiscal elusion and evasion—from fiscal pacts [74,75].

Starting from this perspective, the diverse role of the state—as a partner—and the more pro-active engagement of society and economic firms should be promoted by providing value to pre-existing practices. This mode of thinking also entails a reassessment of the adopted value creation models. Circular economy models, sustainable processes, and collaborative and social/civil economies are seen in various ways as possible pathways for change. In terms of services and societal relationships, besides the Beveridge welfare model based on public intervention, the core economy must reevaluate its active societal role and its voluntary elements in society [63].

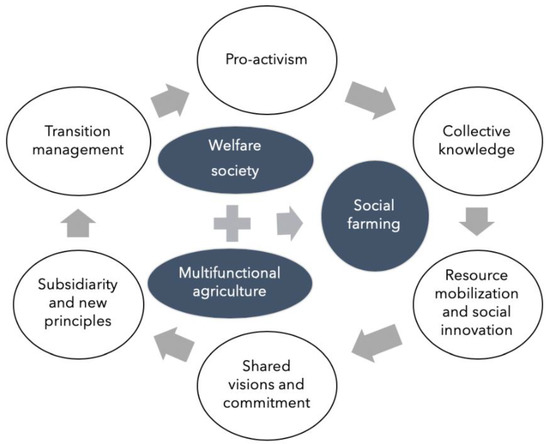

For arising crises (economic, financial, social, and environmental), part of the debate on innovative welfare solutions focuses on the passage from state intervention to social impacts, regenerative solutions, and the organization of a welfare society [8,59,60,61,62]. The pro-active participation of society and the organization of a stronger subsidiarity among public and private actors (NGOs, civil society, and private firms) are considered possible paths to build innovative visions and mobilize, in a collective way, the resources needed to enlarge the living spaces of society. The proposed work scheme has effective applications in social farming, where the development of innovative initiatives in the area is achieved via multi-stakeholder paths of social innovation. In these paths, agricultural resources are mobilized for other purposes, including those related to the innovation of social health services for people and communities (Figure 4).

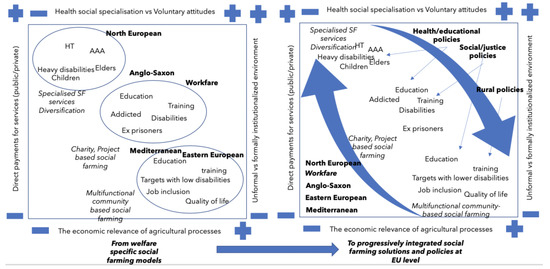

Figure 4.

Redesigning a welfare society by activating resources from agriculture and nature (source: author).

From this perspective, social farming initiatives can be read as part of the innovative tensions in present-day society. In different ways, and by following diverse models, they mobilize toward social innovation paths through existing resources of agriculture (plants, animals, spaces, nature, and people). A common perspective is to increase and to improve social health services so as to improve access to human rights for different groups of people in need and to reinforce existing social protections. This process is ongoing in Europe and outside Europe in a more or less structured way according to existing welfare models and resources, both in peri-urban and rural areas.

The main demand we should answer is related to the diverse existing models presented in the previous paragraph and what their strengths and weaknesses are for present societal demands and challenges. As noted, three main social farming models—Specialized, Charity/Project, and Community based—are developing under diverse conditions with specific levels of organization, as well as specific and often diverse outcomes (from service provisions to social justice).

Considering a common perspective, how different models can accommodate themselves, what kinds of services would be most resilient (especially under the financial tensions in welfare models), and how to allocate social farming initiatives in the future are part of the aforementioned increasing demand, especially after COVID-19. From this point of view, the social farming models that are more dependent on public resources are also clearly more vulnerable than others (specialized resources more than community-based ones) to financial scarcity. Specialized models strongly focus on the quality of services provided to specific target groups, are strongly based on the professionalization of the actors involved, and are directly supported by public policies or private payments. From this point of view, the main limit is resource dependency that, in times of scarcity, might generate difficulties for the project-holders and the services themselves. Charity/project-funded social farming initiatives are still dependent of public or charity resources, although agricultural processes might also partially support economic sustainability. It is also clear that charity models have strengths in their flexibility and limitations in their dependence on funding.

The community-based model could find innovative solutions to achieve sustainability and thus achieve wider and more indirect community recognition (see subsequent sections), as well as facilitate a social justice path of inclusion accompanying people from social exclusion toward empowerment and active engagement in the agricultural processes to help them achieve professional and economic recognition. On the other hand, without public support, the inclusion of disadvantaged people might more successfully help them actively participate in existing on-farm processes. It is also evident that people more in need demand specific professional attention, as professionalized skills cannot be supported by agricultural economic processes alone; they still require public resources (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Social farming models: principles, targets, and outcomes (source: author).

Again, a growing number of people are in need (and will be even more so in the future), although they are often not classified into official social categories. To fit these needs, public resources will be necessary (see the financial discussion at the EU level), but the future for many people will also be dependent on innovative economic models that are able to offer new paths of personal development according to innovative paths of social/civil economy to revitalize the firms themselves.

From this point of view, the Social Farming Community model fits these re-organizing trends with the relationships between state intervention, societal involvement, the responsibility of firms, and the economic system. In this system, a new ethical consumer attitude might re-frame the space for innovative and multipurpose value creation in terms of environmental, social, and economic perspectives. Such solutions might be able to enlarge this vital space in our limited society. At the same time, we should also consider that for converging challenges and trends, the same welfare models in Europe will gradually converge. Within this path, the social farming initiative and related models should take advantage of the common comprehension of commonalities and diversities to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of all of them and better understand the mix of solutions (from specialized to community-based social farming models) that can best solve existing and emerging demands.

4.5. Social Farming: the Co-Production Paradigm

As described in the previous sections, each existing social farming model presents diverse strengths and weaknesses. The specialized and the charity/project-based social farming initiatives are well-known and do not need further explanation, as they are mainly rooted in the traditional state–market paradigm, where some of the resources produced by the economic system are redistributed for social purposes and from the perspective of a more equal society. The community-based models embedded in societal reform, however, require more detail, where subsidiarity, co-production, and civil/social economy are the main pillars, as we present from Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 and which emerged from the cases collected and organized during our research initiatives.

Table 4.

Biagi Farm (our survey). Website: https://www.facebook.com/PodereAiBiagi/.

Table 5.

Calafata Farm (our survey). Website: http://www.calafata.it.

Table 6.

Orti ETICI (our survey). Website: http://www.ortietici.it.

Table 7.

Turin area (our survey).

The concept of subsidiarity [76,77] is not new. Subsidiarity describes the collaborative participation of different actors according to their recognized roles in the organization of specific activities and services. In the Mediterranean model, and especially in Italy, subsidiarity arose in the beginning of the 1990s with the involvement of the third sector in the organization of the welfare system. At present, the idea of subsidiarity has been expanded to other actors involved in the organization of the community-based social farming model, including private farmers, citizens, and consumers. All of these actors are locally involved in the transition paths and specific areas necessary to reframe their common visions, knowledge, actions, roles, and procedures, in order to redesign the space for maneuvering among different stakeholders and competences [45].

The idea of co-production can have diverse meanings. It can be seen as the co-design of new services, normally with the involvement of the final users (in the economic system, this is instead a marketing activity to affiliate future customers). In the case of social farming, co-design can take part in the interactions between user associations and other stakeholders involved along a transitional management process. At the same time, the co-production idea can be understood as a positive collaboration among public and private actors to reinforce and improve service provisions [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. In social farming activities, it is related to the participation of public and private actors in the re-organization of the local social protection net from the perspective of a welfare society with the participation of public social health institutions and workers, NGOs, farmers and farmer associations, training agencies, and associations of users. Again, co-production can also be seen as the simultaneous production of public and private values and, in the case of social farming, of economic and social attributes and outcomes. The idea of co-production is linked to that of multifunctional agriculture. The latter involves the capability of an agricultural process to simultaneously produce public (landscape, water management, biodiversity, etc.) and private outcomes (mainly food). Such agricultural processes are driven with economic purposes but can accompany people in need to help them reinforce their capabilities.

The participation of disadvantaged people in existing agricultural farm processes might be demanding in terms of attention, especially in the starting phase with the involvement of a new participant. The level of engagement is also dependent on the existing capabilities of the person involved (the lower the person’s capabilities are, the higher their professional support should be, and vice versa). Unlike other social farming models, in the community-based model, the economic sustainability of social activities emerge from an economy of scope. In multifunctional processes, the economy of scope is related to the possibility of providing more outcomes from the same process. For social farming, the possibility to promote social services and the inclusion of pre-existing professional agricultural processes lowers the relevant costs and introduces people in need to the everyday life of a farm, groups of people, and society, thereby facilitating social justice processes.

The idea of multifunctional agriculture was introduced by the OECD in the 1990s to better justify public support to farmers committed to the provision of public goods for so-called ecosystem services (5). The related debates mainly focus on environmental goods, but very few arguments engage with social goods. The demands related to the multifunctional use of agricultural processes for social purposes in the absence of public support are apparent under state and market principles. Why should a farmer collaborate with other public and private stakeholders from the social sector without any direct economic recognition? This question frequently emerges in public debates. On the other hand, the same question can be phrased as follows: how can social farming exist under public financial constraints, and in what ways could our society remain inclusive for disadvantaged people?

To answer the two questions above, we should move from the state–market divide towards other principles that traditionally inform community life: gifts and reciprocity [86,87,88,89]. In this perspective, farmers act with responsibly to answer community needs (in the case of social farming, social demands) and can thereby valorize the economy of scope in multifunctional agricultural processes to generate opportunities for people in need. Local society might react to gifts offered by farmers with reciprocity, by giving more attention to the public and private goods offered by the farmers with specific efforts to support community needs.

The easiest way to act with reciprocity is to offer more visibility and market opportunities for the food provided by farmers. This can happen directly with consumer involvement in short food circuits and direct selling, as well as via local distribution channels.

Local society’s support for responsible farms could reinforce a shift in entrepreneurial attitudes and support the co-production paradigm. At the same time, an improvement in the economic activities organized by social farmers could be translated into emerging job opportunities for the people involved in the social farming activities, which could improve their skills and capabilities and allow them to become workers paid by the social farmers themselves. In this situation, the local actors are involved in a process that should be able to progressively facilitate the shift from a state–market paradigm to a civil economy, where the farmer acts with responsibility to the local community under “for project” rather than “for profit” activities, i.e., projects that mediate the public and private interests of the actors involved.

From this perspective, the provision of public and private goods (economic, social, and (for organic sustainable farming) environmental) does not emerge in many stages of local life (with production first and re-distribution later) but instead happens simultaneously.

This is also why social farming, according to the community-based model, can co-produce values. To move from theory to practice, specific cases are presented in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. These cases were selected from among the action research paths co-managed by Pisa University over the last 10 years. Four of them can be synthetically offered to generate evidence related to the concepts introduced above regarding subsidiarity, co-production, and civic economy in a community-based model. The first two examples (Table 4 and Table 5) are business models organized by a family farm (Table 4) and a farming social cooperative (social cooperative type B and farmer entrepreneurs, according to the national laws) working in the Lucca (Tuscany) area (Table 5). The third one is a partnership among public and private NGOs working in the Pisa area on university farmland (Table 6), and the fourth one is related to a project in the Turin area involving about 90 actors (Table 7).

Each case includes its history and main motives, as well as its ongoing activities, targets, future strategies, and main driving principles in terms of subsidiarity, co-production, and civil economy. In all cases, the strong motivations of the project leaders and all the actors involved stand out, as well as their abilities to listen to, propose, and elaborate solutions. These tables also include the networking activities needed for the projects to generate innovative paths and solutions, their ability to organize collaboration among diverse actors (public and private) in a space of freedom, their radical thinking attitudes for generating alternative solutions, their effectiveness in redesigning local value creation, their ability to generate positive interfaces between diverse actors to define innovative solutions, their ability to avoid or reduce conflicting positions and incorporate the main local stakeholders to develop win–win solutions, their ability to generate large-impact initiatives in terms of social and economic results, the resilience of the projects in the long-term, and their ability to enlarge their influence and potential impact over time. These data also illustrate each project’s ability to grow in times of crisis, like in the COVID-19 situation, mainly because they are less dependent on public funds.

4.6. Social Farming Looking Forward

In our paper, we focused on social farming initiatives across Europe and abroad in order to design a conceptual framework and better understand the emerging social farming models, as well as their strengths and weaknesses relative to the main challenges experienced by modern society. Our framework shows how the same resources—land, nature, agricultural processes, farm spaces, and project holders—are activated differently when they are organized under diverse welfare models and exposed to different driving trends. In this framework, agricultural resources are mobilized according to social innovation processes that take place in emerging local arenas where local, regional, and national public and private actors are involved, without any tension or possible competition.

Existing models (specialized, charity/project-based, and community-based models) have various strengths and weaknesses. What is clearly evident is the diversity between models based on an agricultural diversification perspective (i.e., the specialized social farming model), those where agricultural projects are socially useful but not always economically sustainable (those that need charity/project support), and multifunctional projects, where the co-production of agricultural processes (in terms of private and public goods and economic and social values) is a relevant perspective. The first two are more embedded in a social health framework (and funded with public/charity resources), while the latter are more inspired by the organization of informal living environments and organized based on a co-production paradigm, where the effectiveness of agricultural processes remains part of the project’s sustainability independent from the actors involved (i.e., responsible private firms or entrepreneurship NGOs).

Today, each model is strongly embedded in mainstream local welfare (Figure 6). At the same time, in Europe, under growing social, economic, and environmental challenges, a converging reflection on existing models (not only in social farming) and their possible adaptations to increasing constraints remains ongoing. Social farming could be a useful and effective resource in this process to consolidate and even enlarge existing social protections in both urban and rural areas, as well as for diverse groups of people.

Figure 6.

Social farming in Europe and abroad with individual models forming a broader web (source: author).

Looking at the inspiring principles of different social farming models, some of them remain embedded in the state–market divide and can increase the effective management of available public resources. Models based on co-production could better respond to existing and forthcoming economic and social crises, as they are able to, simultaneously, produce economic and social values and public and private goods and reshape the relationships between firms and society from the perspective of a civil economy that is more focused on community needs than profit. After the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, strong efforts in many countries should be organized to redesign value creation models from an economic, social, and environmental perspective.

Reflecting on the three different models and on their different opportunities and threats, a broader social farming web, according to the expected outcomes in continuity with each other, could be designed to better fit the diverse needs of potential users and reinforce social protections, both in rural and peri-urban areas. Models that are currently framed as specific and differentiated models could also be interpreted from the perspective of a growing integrated European social farming web, where diverse models and practices can be allocated under different policies (health, social, education, justice, and rural policies) to offer more fluidity and flexibility for the people engaged according to their evolving needs. From more specialized solutions to models that are able to better embed disadvantaged people in the everyday society and even their professional and economic recognition in local community, social farming seems to open a space of action where single actors and local/regional/national institutions can engage their efforts to generate new visions, thinking, and solutions.

This might also become possible under the perspective of a progressive area of convergence among diverse existing welfare models and under the pressure of more common constraints.

5. Concluding Remarks

Social farming in Europe and abroad still has little supporting evidence, although such farms have rich potential in term of the services they provide, their areas for intervention, their costs and effectiveness, their impacts on users, their pathways for transition, their commitment to the people involved, and their emerging innovative paradigms. From all the mentioned perspectives, social farming might offer many lessons for current crises.

Social farming offers many resources to achieve a better living space for all. From this point of view, social farming deserves to be better analyzed and supported by different policy streams. Social farming can also support the development of regenerative cities and sustainable local systems around the urban areas where most of the population lives (as introduced by FAO). In rural areas, social farming could provide the services that are needed to ensure a vibrant community, generational renewal, and sustainable economies. Especially in rural areas, it is increasingly clear that without social services, it will be difficult to ensure effective and equal economic activities, especially under stronger migratory flows.

The organization of a social farming web that is able to valorize different models according to various needs and outcomes is demanding in terms of policy reorganization. At the national and EU level, it remains difficult to move past narrow, pre-existing specialized views. Social policies, health policies, and rural and agricultural policies are still specialized and remain focused on traditional actors and solutions. On the contrary, based on our reflection, it appears clear that a social farming web is not a mode-based solution. To take advantage of these diverse models, diverse policies should be implemented (including health, social, justice, education, and rural policies) according to the expected outcomes (primarily in terms of health, social results, urban regeneration, and economic rural re-design). This still seems to require a long transition path. Examples from the forthcoming rural development policies of social farming are still mainly considered only with reference to migration management.

What also emerges from European research is the high level of engagement of researchers in action research paths. This is related to two different aspects: On the one hand, the role of researchers as a third party in mediation processes is linked to the local pathways for change where actors are engaged; on the other hand, it is difficult to approach a field where people demonstrate strong social commitments in an instrumental way. From the perspective of responsible research and innovation (where diversity and inclusion, anticipation and reflexivity, openness and transparency, and adaptability and flexibility are the main elements), more research projects at the EU level should be developed according to an EU research perspective. Social farming in Europe is (in addition to research activities) strongly supported by the European networking and research driven by past EU projects. Today, it seems even more relevant to reorganize specific lines of research on topics related to innovative business and service solutions to produce greater sustainability from economic, societal, and environmental perspectives. This is an area of investigation where social farming can offer new insights and useful solutions.

Funding

This research received funds from Pisa University for its publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stuiver, M. Highlighting the retro-side of innovation and its potential for regime change in agriculture. In Between the Global and the Local: Confronting Complexity in the Contemporary Agri-Food Sector; Marsden, T., Murdoch, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 12, pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; O’Connor, D. Supporting Policies for Social Farming in Europe. Progressing Multifunctionality in Responsive Rural Areas; ARSIA: Firenze, Italia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.; Groot, J.C.; Van Der Ploeg, J.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D.; Stobbelaar, D.; Van Ittersum, M.; Van Ittersum, M. Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, S112–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Vandermeulen, V.; Mettepenningen, E.; Verspecht, A. Multifunctionality of Agriculture: A Review of Definitions, Evidence and Instruments. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2007, 1, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharo, E.; Daily, G.C. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Da Rocha, S.M.; Almassy, D.; Pinte, L. Social and Cultural Values and Impacts of Nature-Based Solutions and Natural Areas. May 2017. Available online: https://naturvation.eu/sites/default/files/result/files/naturvation_social_and_cultural_values_and_impacts_of_nature-based_solutions_and_natural_areas.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Dessein, J.; Bock, B.B.; De Krom, M. Investigating the limits of multifunctional agriculture as the dominant frame for Green Care in agriculture in Flanders and the Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 32, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, I.; Mushövel, F.; Niblett, R.; Vandenbroucke, F.; Rinaldi, D.; Wolff, G.; Wilson, K.; Hüttl, P.; Hellström, E.; Kosonen, M. Redesigning European Welfare States—Ways Forward, Vision Europe Summit. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/29644900/Redesigning_European_welfare_states_Ways_forward (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Barnes, M. Care, deliberation and social justice. In Proceedings of the Community of practice Farming for Health, Ghent, Belgium, 6–9 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Moruzzo, R.; Rossignoli, C.; Scarpellini, P. Innovating Rural Welfare in the Context of Civicness, Subsidiarity and Co-Production: Social Farming. In Proceedings of the 3rd EURUFU Scientific Conference, Social Issues and Health Care in Rural Areas, Sondershausen, Germany, 25 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Iacovo, F.; Petrics, H.; Rossignoli, C. Social Farming and social protection in developing countries in the perspective of sustainable rural development in Agriculture in an urbanizing society: Reconnecting agriculture and food chains to societal needs. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Agriculture in an Urbanizing Society Reconnecting Agriculture and Food Chains to Societal Needs, Rome, Italy, 14–17 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Leck, C.; Evans, N.; Upton, D. Agriculture–Who cares? An investigation of ‘care farming’ in the UK. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 34, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudcová, E.; Chovanec, T.; Moudry, J. Social Entrepreneurship in Agriculture, a Sustainable Practice for Social and Economic Cohesion in Rural Areas: The Case of the Czech Republic. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramm, V.; Torre, C.D.; Membretti, A. Farms in Progress-Providing Childcare Services as a Means of Empowering Women Farmers in South Tyrol, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Olio, M.; Hassink, J.; Vaandrager, L. The development of social farming in Italy: A qualitative inquiry across four regions. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Hulsink, W.; Grin, J. Farming with care: The evolution of care farming in the Netherlands. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 68, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, W. The innovative model of Community-based Social Farming (CSF). J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 60, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriggi, A. Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship: A participatory study of Green Care practices in Finland. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 15, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirado, C.; Valldeperas, N.; Tulla, A.F.; Sendra, L.; Perpinyà, A.B.I.; Evard, C.; Cebollada, À.; Espluga, J.; Pallarès, I.; Vera, A. Social farming in Catalonia: Rural local development, employment opportunities and empowerment for people at risk of social exclusion. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 56, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slámová, M.; Belčáková, I. The Role of Small Farm Activities for the Sustainable Management of Agricultural Landscapes: Case Studies from Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.S. Social Farming as a New Opportunity for Agriculture in Korea, FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform. Available online: http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=756 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Sofar Project. Available online: http://sofar.unipi.it/index.htm (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Sofaredu. Available online: https://sofaredu.eu (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Innpatunet. Available online: https://www.innpatunet.no (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Green Care Austria. Available online: http://www.greencare.at (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Social Faming in Czech Republic. Available online: www.socialni-zemedelstvi.cz (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Maie Project. Available online: https://www.maie-project.org/index.php-id=89&L=4.html (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Social Farmning in Ireland. Available online: https://www.socialfarmingireland.ie (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Social Farming in UK. Available online: https://www.farmgarden.org.uk (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Green Care Coalition in UK. Available online: https://greencarecoalition.org.uk (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Social Faming in the Visegrad Countries. Available online: http://www.socialni-zemedelstvi.cz/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/social-farms-in-visegrad-countries-web.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Profarm Project. Available online: http://profarmproject.eu (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Inclufar Project. Available online: http://www.inclufar.eu/en/ (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Green Care Finland. Available online: http://www.gcfinland.fi/in-english/ (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Green Care in Agriculture. Health Effects, Economics, and Policies. Available online: https://www.cost.eu/publications/green-care-in-agriculture-health-effects-economics-and-policies/ (accessed on 29 April 2020).