Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Methodology and Questionnaire

2.1.1. Consumers’ Preferences for CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector

2.1.2. Label Mapping

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Wine Consumption Habits

3.3. CSR Preferences for Consumers

3.4. CSR Information Conveyed by the Four Wine Certifications

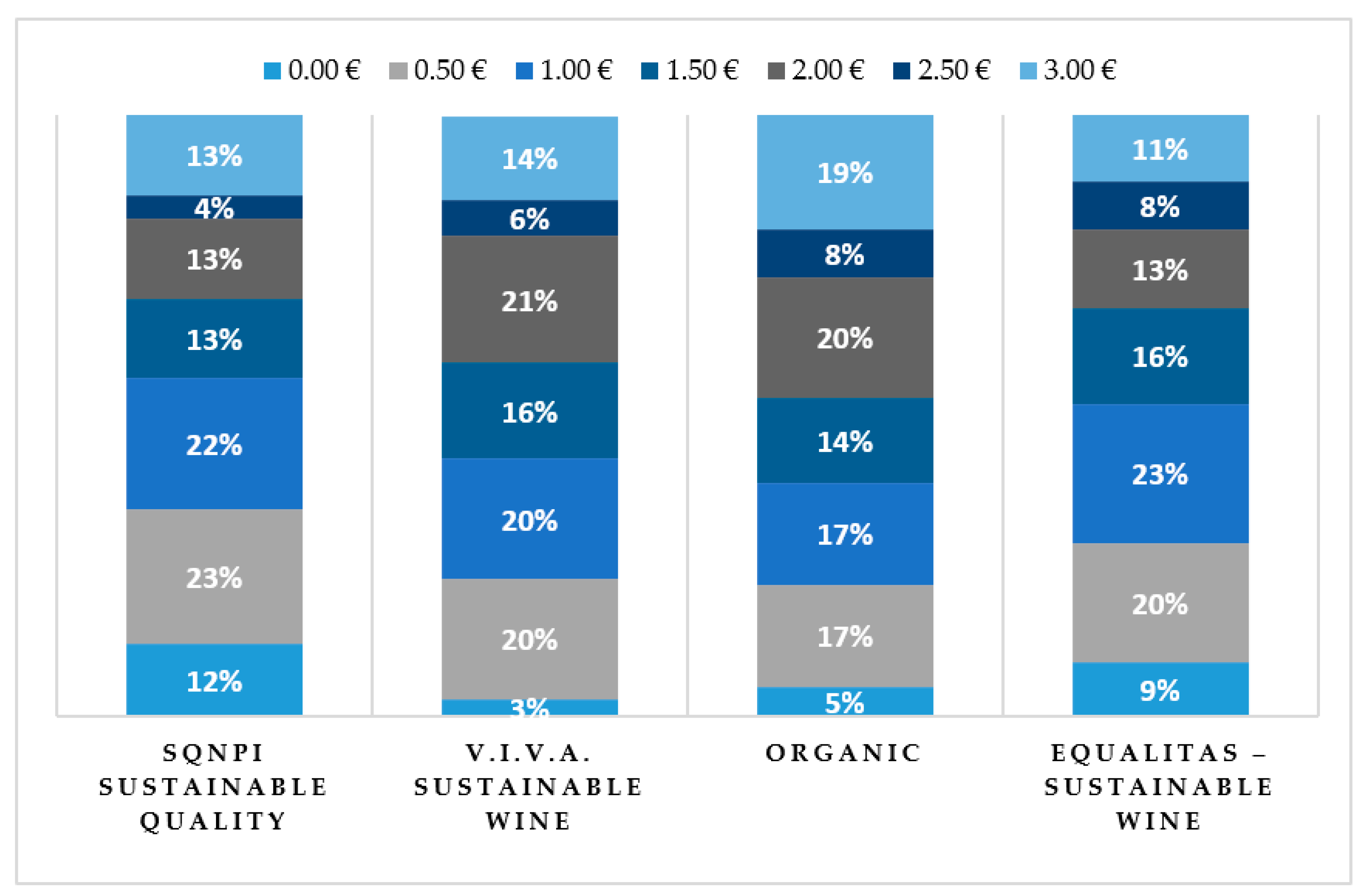

3.5. Consumers’ price premium for the Wine Certifications

4. Discussion

5. Study Implications and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Innovation trends in the food industry: the case of functional foods. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2013, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, E.; Giachino, C.; Bertoldi, B.; Stupino, M. Innovativeness of Ceretto Aziende Vitivinicole: A First Investigation into a Wine Company. Int. Food Agribus. Man. 2014, 17, 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vita, G.; Chinnici, G.; Pappalardo, G.; D’Amico, M.; Bracco, S. Standard output versus standard gross margin, a new paradigm in the EU farm economic typology: what are the implications for wine-grape growers? J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapporto 2019 ISMEA—Qualivita sulle produzioni agroalimentari e vitivinicole italiane DOP, IGP e STG. Available online: http://www.ismea.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeAttachment.php/L/IT/D/d%252F1%252Fc%252FD.5dc105037cf9be92b910/P/BLOB%3AID%3D10971/E/pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Corsi, A.; Mazzarino, S.; Pomarici, E. The Italian Wine Industry. In The Palgrave Handbook of Wine Industry Economics; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Agricultural Heritage Systems and Landscape Perception among Tourists. The Case of Lamole, Chianti (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asero, V.; Patti, S. From wine production to wine tourism experience: the case of Italy. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46471640_From_Wine_Production_to_Wine_Tourism_Experience_The_Case_of_Italy (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Consumers’ Preferences for Wine Attributes: A best–worst Scaling Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas, R.; Spadoni, R. Is innovation needed in the Old World wine market? The perception of Italian stakeholders. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Lerro, M.; Chrysochou, P.; Vecchio, R.; Krystallis, A. One size does (obviously not) fit all: Using product attributes for wine market segmentation. Wine Econ. Policy 2017, 6, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Mora, C.; Menozzi, D. Factors driving sustainable choice: The case of wine. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajdakowska, M.; Jankowski, P.; Gutkowska, K.; Guzek, D.; Żakowska-Biemans, S.; Ozimek, I. Consumer acceptance of innovations in food: A survey among Polish consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Lisanti, M.T.; Caracciolo, F.; Cembalo, L.; Gambuti, A.; Moio, L.; Siani, T.; Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C.; Piombino, P. The role of production process and information on quality expectations and perceptions of sparkling wines. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Public goods production and value creation in wineries: a structural equation modelling. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Vecchio, R.; Nazzaro, C.; Pomarici, E. The growing (good) bubbles: Insights into US consumers of sparkling wine. Br. Food J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G.; Rivetti, F. Responsible innovation in the wine sector: A distinctive value strategy. Agric. Agric. Sci. 2016, 8, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, D.; Malandrino, O.; Esposito, B.; Supino, S.; Sessa, M.R. The Pathway towards Social Responsibility in Italian Wine Sector: The Feudi di San Gregorio SpA Experience. J. Health Sci. 2019, 7, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Lerro, M.; Vecchio, R.; Caracciolo, F.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ heterogeneous preferences for corporate social responsibility in the food industry. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Ma. 2018, 25, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Responsabilità Sociale e Creazione di Valore Nell’impresa Agroalimentare: Nuove Frontiere Di Ricerca. Econ. Agro-Alimentare 2012, 42, 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsch, J.; Gupta, S.; Grau, L.S. An Exploratory Study Framework for Understanding Programs Corporte Social Responsibility as a Continuum: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 70, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Raimondo, M.; Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Marotta, G. Cause Related Marketing among Millennial Consumers: The Role of Trust and Loyalty in the Food Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G. The Life Cycle of Corporate Social Responsibility in Agri-Food: Value Creation Models. Sustainaility 2020, 12, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deselnicu, O.; Costanigro, M.; Thilmany, D.D. Corporate social responsibility initiatives and consumer preferences in the dairy industry. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/agsaaea12/124616.htm (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M. How the social responsibility creates value: Models of innovation in Italian pasta industry. IJGSB 2017, 9, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Sarnacchiaro, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer preference: A structural equation analysis. Corp. Soc. Resp. Env. Ma. 2018, 25, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Massa, I. Modeling social life cycle assessment framework for the Italian wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Theuvsen, L. Influences on consumer attitudes towards CSR in agribusiness. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/166108/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Morgan, C.J.; Widmar, N.J.O.; Wilcoxc, M.D.; Croney, C.C. Perceptions of agriculture and food corporate social responsibility. J. Food Prod. Market 2018, 24, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.T.; Deselnicu, O.; Costanigro, M. How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives: A Cluster Analysis of Dairy Consumers. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2013, 44, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Costanigro, M.; Deselnicu, O.; McFadden, D.T. Product differentiation via corporate social responsibility: consumer priorities and the mediating role of food labels. Agr. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, H.; Theuvsen, L. CSR activities in the German poultry sector: differencing preference groups. Int. Food Agribus. Man. 2016, 20, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, T.; Stranieri, S.; Caracciolo, F.; Ricci, E.C.; Cembalo, L.; Banterle, A.; Cicia, G. Corporate Social Responsibility certifications influence consumer preferences and seafood market price. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäufele, I.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions, preferences and willingness-to-pay for wine with sustainability characteristics: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Cullen, R.; Wratten, S.D.; Fountain, J. Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: an exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G.; Monaco, L. Exploring environmental consciousness and consumer preferences for organic wines without sulfites. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 120, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, P.; Saunders, C.; Dalziel, P.; Rutherford, P.; Driver, T.; Guenther, M. Estimating wine consumer preferences for sustainability attributes: A discrete choice experiment of Californian Sauvignon blanc purchasers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers-Rubio, R. Would you Pay a Price Premium for a Sustainable Wine? The Voice of the Spanish Consumer. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, R. Determinants of willingness-to-pay for sustainable wine: Evidence from experimental auctions. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassler, B. How green is your ‘Grüner’? Millennial wine consumers’ preferences and willingness-to-pay for eco-labeled wine. Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Agrarökonomie 2015, 24, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Corbo, C.; Lamastra, L.; Capri, E. From environmental to sustainability programs: a review of sustainability initiatives in the Italian wine sector. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G. A cross-national comparison of sustainability in the wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianoni, S.; Marchettini, N.; Panzieri, M.; Tiezzi, E. Sustainability assessment of a farm in the Chianti area (Italy). J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchettini, N.; Panzieri, M.; Niccolucci, V.; Bastianoni, S.; Borsa, S. Sustainability indicators for environmental performance and sustainability assessment of the production of four Italian wines. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 2003, 10, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, S.; di Bene, C.; Galli, M.; Remorini, D.; Massa, R.; Bonari, E. Greenhouse gas emissions in the agricultural phase of wine production in the Maremma rural district in Tuscany, Italy. Ital. J. Agron. 2011, 6, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Rowe, I.; Rugani, B.; Benetto, E. Tapping carbon footprint variations in the European wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 43, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Beccali, G.; Cellura, M.; Marvuglia, A. POEMS: A Case Study of an Italian Wine-Producing Firm. Environ. Manag. 2006, 38, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R.; Verneau, F. A future of sustainable wine? A reasoned review and discussion of ongoing programs around the world. Calitatea 2014, 15, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sogari, G.; Corbo, C.; Macconi, M.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. Consumer attitude towards sustainable-labelled wine: An exploratory approach. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2015, 27, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Applying best–worst scaling to wine marketing. IJWBR 2009, 21, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J.J. Determining the Appropriate Response to Evidence of Public Concern: The Case of Food Safety. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; DeVinney, T.M.; Louviere, J. Using Best–Worst Scaling Methodology to Investigate Consumer Ethical Beliefs Across Countries. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 70, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.; Eckert, C.; Davis, S. Segmenting consumers’ reasons for and against ethical consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 2237–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Measuring consumers’ preferences for craft beer attributes through best–worst Scaling. AFE 2020, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lusk, G. Food values. Science 1917, 45, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goodman, S.; Lockshin, L.; Cohen, E.; Fensterseifer, J.; Ma, H.; d’Hauteville, F.; Jaeger, S. International comparison of consumer choice for wine: A twelve country comparison. In Proceedings of the 4th international conference of the academy of wine business research, Siena, Italy, 17–19 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas Molla-Bauza, M.; Martinez-Carrasco Martinez, L.; Martinez Poveda, A.; Rico Perez, M. Determination of the surplus that consumers are willing to pay for an organic wine. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2005, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, K.; Burch, D.; Lawrence, G.; Lockie, S. Contrasting paths of corporate greening in Antipodean agriculture: organics and green production. Jansen, K., Vellema, S., Eds.; In Agribusiness and Society: Corporate Responses to Environmentalism, Market Opportunities and Public Regulation; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pomarici, E.; Amato, M.; Vecchio, R. Environmental friendly wines: a consumer segmentation study. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Pucci, T.; Aquilani, B.; Zanni, L. Millennial generation and environmental sustainability: The role of social media in the consumer purchasing behavior for wine. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loose, S.M.; Remaud, H. Impact of corporate social responsibility claims on consumer food choice: A cross-cultural comparison. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 142–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.C.; Makatouni, A. Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Grunert, K.G. The perceived healthiness of functional foods: a conjoint study of Danish, Finnish and American consumers’ perception of functional foods. Appetite 2003, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.K.; Arvola, A.; Hursti, U.K.K.; Åberg, L.; Sjödén, P.O. Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behaviour. Appetite 2003, 40, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggeman, B.C.; Lusk, J.L. Preferences for fairness and equity in the food system. Eur. Rev. Agric. 2011, 38, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Certification | Logo | Description |

|---|---|---|

| SQNPI Sustainable Quality |  | This certification shows that the wine was obtained from grapes treated with integrated cultivation practices (e.g., limitation in the use of chemicals on grapes). |

| V.I.V.A. Sustainable Wine |  | This certification shows that the winery respects specific sustainability standards both in vineyard and cellar. Sustainability is assessed by four indicators: air, water, vineyard, and territory. |

| Organic |  | This certification shows that the wine is organic and employs grapes obtained by cultivation practices that ban the use of pesticides or chemical fertilizers. Further, the wine has a reduced sulfite content. |

| Equalitas—Sustainable Wine |  | This certification shows that wine meets specific sustainability standards and is obtained adopting good agronomic and cellar practices, as well as social (relationships with local stakeholders) and economic initiatives (employees’ incentives and fair prices for suppliers). |

| CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector | Description |

|---|---|

| Energy consumption | The winery’s involvement in reducing energy consumption in the vineyard and cellar and/or to using energy produced from renewable sources. |

| Water consumption | The winery’s involvement in reducing water consumption, also adopting a water recycling system in cellar. |

| Air pollution | The winery’s involvement in reducing the emissions generated by its activities and consequently their impact on climate change. |

| Support for the local community | The winery’s involvement in supporting donations to and/or sponsorships of local initiatives (e.g., cultural, sports, etc.). |

| Attention to the employees | The winery’s involvement in giving all workers the same opportunities as well as fair or higher than market wages. |

| Fair trade | The winery’s involvement in supporting the economic development of the territory and suppliers (e.g., ensuring a guaranteed minimum price). |

| Waste management | The winery’s involvement in valorizing, internally, the byproducts produced (e.g., fertilizers) and/or in other sectors (e.g., cosmetics, animal husbandry, energy, etc.). |

| Sustainable agronomic practices | The winery’s involvement in adopting sustainable agronomic practices aimed at preserving soil fertility and reducing the environmental impact. |

| Health and food safety | The winery’s involvement in reducing the use of chemical products both in vineyard and cellar (e.g., wines with reduced sulfite content). |

| Biodiversity | The winery’s involvement in preserving biodiversity in the vineyard, promoting the development of spontaneous flora and fauna. |

| Sustainable packaging | The winery’s involvement in adopting recyclable packaging and/or reducing environmental impact such as corks made of glass or sugar cane and light glass bottles. |

| Which of the Following Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives do you Think are the Most Important and Least Important Aspects that a Winery Should Focus On? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Most important | Least important | |

| □ | Water consumption | □ |

| □ | Biodiversity | □ |

| □ | Waste management | □ |

| □ | Health and food security | □ |

| □ | Sustainable packaging | □ |

| Variable Name and Description | Mean | Frequency | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.390 | N/A | 0 | 1 | |

| Female | 39.0% | ||||

| Male | 61.0% | ||||

| Respondent’s age | 40.813 | 11.962 | 18 | 75 | |

| Household size | 3.251 | 1.175 | 1 | 8 | |

| Education level classes Primary school Secondary school High school University degree Above university degree | 3.936 | 0.0% 3.2% 24.3% 48.2% 24.3% | 0.782 | 1 | 5 |

| Occupation status Employed Self-employed Housewife/husband Retired Student Unemployed | 1.892 | 51.8% 34.3% 0.8% 2.0% 8.4% 2.7% | 1.342 | 1 | 6 |

| Family monthly income classes <€2000 €2001–€4000 €4001–€6000 €6001–€8000 >€8000 | 2.657 | 19.9% 38.7% 15.1% 8.4% 17.9% | 1.369 | 1 | 5 |

| Variable Name and Description | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Wine consumption frequency Every day 4–5 times per week 2–3 times per week Once a week 2–3 times per month Once a month | 20.3% 7.6% 22.3% 19.9% 13.9% 16.0% |

| Favorite wine place of purchase Supermarket, hypermarket, discount store Directly from the producer Pub/restaurant Wine bar Online Others | 35.1% 32.7% 9.2% 13.5% 4.4% 5.1% |

| Favorite wine place of consumption At home At friends’ homes Pub/restaurant Lounge bar/wine bar | 55.8% 21.1% 18.3% 4.8% |

| Favorite wine consumption occasion Lunch Aperitif Dinner After dinner Party Others | 19.9% 4.4% 62.2% 2.0% 10.8% 0.7% |

| Wine purchase by price point <€5.00 between €5.01–€10.00 between €10.01–€15.00 between €15.01–€20.00 between €20.01–€25.00 >€25.01 | 24.3% 39.0% 16.7% 15.1% 3.2% 1.7% |

| CSR Initiatives | Total Best | Total Worst | B–W Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and food safety | 710 | −44 | 666 |

| Sustainable agricultural practices | 449 | −112 | 337 |

| Air pollution | 284 | −123 | 161 |

| Waste management | 186 | −147 | 39 |

| Water consumption | 206 | −184 | 22 |

| Attention to the employees | 209 | −228 | −19 |

| Biodiversity | 152 | −182 | −30 |

| Support for the local community | 227 | −307 | −80 |

| Fair trade | 103 | −399 | −296 |

| Sustainable packaging | 102 | −422 | −320 |

| Energy consumption | 95 | −433 | −338 |

| CSR Initiatives | Average B–W Score | Mean Comparison * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and food safety | 0.765 | |||

| Sustainable agronomic practices | 0.634 | |||

| Air pollution | 0.564 | |||

| Waste management | 0.516 | X | ||

| Water consumption | 0.509 | X | ||

| Attention to the employees | 0.492 | X | X | |

| Biodiversity | 0.488 | X | X | |

| Support for the local community | 0.468 | X | ||

| Fair trade | 0.382 | X | ||

| Sustainable packaging | 0.373 | X | ||

| Energy consumption | 0.365 | X | ||

| Certification | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQNPI Sustainable Quality | 1.29 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| V.I.V.A. Sustainable Wine | 1.53 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Organic | 1.66 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

| Equalitas—Sustainable Wine | 1.37 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 3.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanco, M.; Lerro, M. Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135230

Stanco M, Lerro M. Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135230

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanco, Marcello, and Marco Lerro. 2020. "Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135230

APA StyleStanco, M., & Lerro, M. (2020). Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector. Sustainability, 12(13), 5230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135230