A Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Providing a platform for sharing crisis management related knowledge in terms of experience, solutions on practical problems, development of instruments such as doctrines, procedures, and equipment;

- Facilitating professional communications and information sharing among various crisis management stakeholders, between and within specialised organisations, trainers, research communities, industry, software producers, and other actors, as well as throughout the European community and citizens for strengthening disaster response volunteerism and resilience;

- Affording the integration of various datasets;

- Providing decision support in every functional area of crisis management, as well as for most specific tasks;

- Offering semantic frameworks for the crisis management organisation of professional and volunteer formations, as well as for national crisis command and management architectures;

- Exploring the hazards-related professional vocabulary;

- Helping focused gap analyses throughout the spectrum of crisis management;

- Representing case-specific semantics for the development of solutions and tools;

- Providing a tool for the study of issues in disaster sociology and crisis management.

2. Design Methodology and Underlying Concepts

2.1. Requirements

2.2. Key Concepts

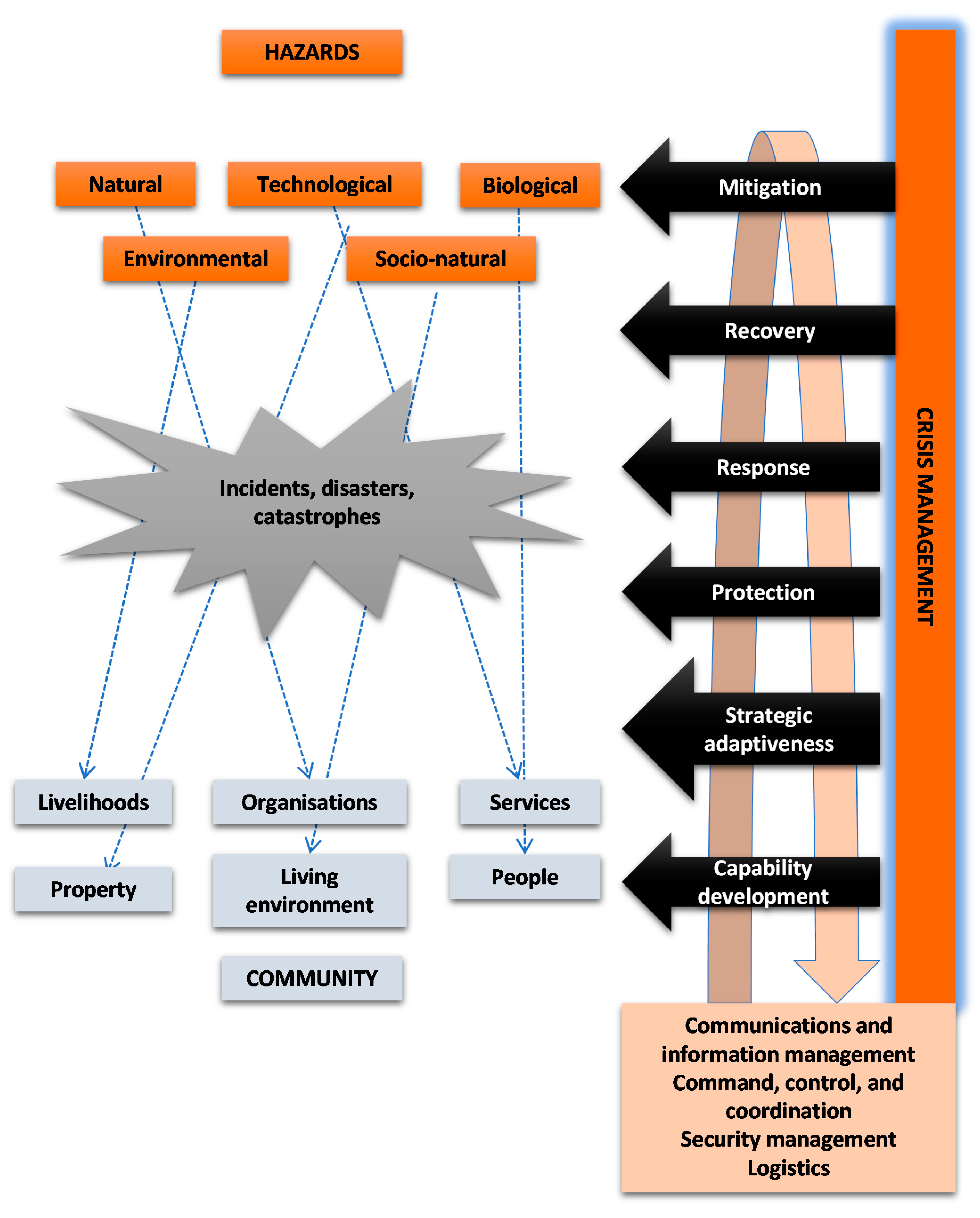

Communities of people with their properties (public and private, cultural, infrastructure and assets, resources); state and private livelihoods; the work of commercial, administrative and non-for-profit organisations; governmental, commercial, and voluntary services; and environment (natural and built) may be considered as a system. The socio-political context influences this system, which may generate and is exposed to hazards and threats. A set of socio-political instruments must be built and used to minimise the risks from identified hazards and threats. In case risk management fails and communities enter a crisis, then measures to respond effectively, provide relief and recovery should be available and promptly undertaken. The understanding of causal relationships in public protection facilitates the decision making on hazards’ mitigation, reduction of vulnerabilities, strengthening response and recovery capabilities and readiness, and generally, in building community resilience.

2.2.1. Hazard, Vulnerability, and Risk

- “Natural hazards: Floods; Severe weather; Wild/Forest fires; Earthquakes; Pandemics/epidemics; and Livestock epidemics.

- Manmade hazards: Industrial accidents; Nuclear/radiological accidents; Transport accidents; Loss of critical infrastructure; Cyberattacks; and Terrorist attacks” [29].

- A natural hazard is an “unexpected and/or uncontrollable natural event of an unusual magnitude that might threaten people” [33];

- A technological hazard is “a hazard originating from technological or industrial conditions, including accidents, dangerous procedures, infrastructure failure or specific human activities, that may cause loss of life, injury, illness or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage” [27];

- A biological hazard is a “process or phenomenon of organic origin or conveyed by biological vectors, including exposure to pathogenic micro-organisms, toxins and bioactive substances that may cause loss of life, injury, illness or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage” [27];

- An environmental hazard is “any single or combination of toxic chemical, biological, or physical agents in the environment, resulting from human activities or natural processes, that may impact the health of exposed subjects, including pollutants such as heavy metals, pesticides, biological contaminants, toxic waste, industrial and home chemicals” [27];

- A socio-natural hazard is “the phenomenon of increased occurrence of certain geophysical and hydro-meteorological hazard events, such as landslides, flooding, land subsidence and drought, that arise from the interaction of natural hazards with overexploited or degraded land and environmental resources” [27].

- “The terms ‘probability’ or ‘likelihood’ are understood as the probability or likelihood of the risk occurring or taking place in the future;

- ‘Consequence’ or ‘impact’ are understood as negative effects of the disaster or risk expressed in terms of human impacts, economic/infrastructure impacts and environmental impacts” [29].

2.2.2. Community

- The people in a concrete geographical area as demographics, respect to the safety regulations, willingness to participate in governmental mitigation and resilience-building programmes, attitude towards voluntarism and mutual help, historical experience, and emergency-related skills;

- Peoples’ property, e.g., possession of infrastructure, land, forests, small dams, and the like, mobile communications and other assets usable for crisis management, public and cultural infrastructure within the area;

- Existing voluntary, formal, or not-for-profit organisations that might be involved in crisis management;

- Services provided by different jurisdictions, as well as commercial and voluntary services;

- The dominant sources of livelihood and their dependencies on plausible hazards;

- The living environment, both built and natural.

2.2.3. Consequence-Based Concepts: Incident, Disaster, Catastrophe, and Crisis

- “A catastrophe is defined by the magnitude of the event on an area, the capacity and ability to respond, and the time to recover” (National Homeland Security Consortium Meeting, December 2005, quoted in [46]);

- “There is a fundamental difference in the preparation, complexity, quality of effort, and scope of catastrophic disaster as opposed to a major natural disaster” [47];

- “Most or all of the community-built structure is heavily impacted” [48];

- “In a catastrophe, most if not all places of work, recreation, worship and education such as schools totally shut down and the lifeline infrastructures is so badly disrupted that there will be stoppages or extensive shortages of electricity, water, mail or phone services as well as other means of communication and transportation” [48];

- “Most, if not all, of the normal, everyday community functions are sharply and simultaneously interrupted” [25];

- “Local officials are unable to undertake their usual work role, and this often extends into the recovery period” [48];

- “…the response and recovery capabilities needed during a catastrophic event differ significantly from those required to respond to and recover from a ‘normal disaster’” [49];

- “A catastrophe, however, overwhelms state and local governments and requires a federal response that anticipates needs instead of waiting for requests from below” [50];

- “Help from nearby communities cannot be provided” [48];

- “In catastrophes, compared to disasters, the mass media differ in certain important aspects. There is much more and longer coverage by national mass media. This is partly because local coverage is reduced if not totally down or out” [48];

- “In catastrophes, there is a need for a more agile, adaptable and creative emergency management” [51].

Crises involve events and processes that carry severe threat, uncertainty, an unknown outcome, and urgency… Most crises have trigger points so critical as to leave historical marks on nations, groups, and individual lives. Crises are historical points of reference, distinguishing between the past and the present… Crises consist of a ‘short chain of events that destroy or drastically weaken’ a condition of equilibrium and the effectiveness of a system or regime within a period of days, weeks, or hours rather than years… Surprises characterize the dynamics of crisis situations… Some crises are processes of events leading to a level of criticality or degree of intensity generally out of control.

2.2.4. Management-Based Concepts: Incident, Disaster, and Crisis Management

2.3. Conceptual Model

2.3.1. Basic Assumptions

In view of the significant increase in the numbers and severity of natural and manmade disasters in recent years and in a situation where future disasters will be more extreme and more complex with far-reaching and longer-term consequences as a result, in particular, of climate change and the potential interaction between several natural and technological hazards, an integrated approach to disaster management is increasingly important.[44]

- The scope and impact of natural and manmade hazards and threats to European communities evolve and challenge the European collective crisis management mechanism and national capabilities;

- The importance of the civil protection function as a component of the European and national internal security is growing;

- There is a growing need, as well as willingness for joint operations for crisis management and disaster resilience [67];

- Crisis management at the European and national level needs better evidence-based investment decision making for building a well balanced comprehensive Portfolio of Solutions in terms of tools, operational concepts, and approaches.

2.3.2. Approach

- Citizens, private subjects, and public authorities;

- Strategy, policy, and operations;

- Missions, functions, and tasks;

- Organisations, processes, and activities;

- Human as well material resources, and real estate;

- Command, control, coordination, management, etc.

2.3.3. Context

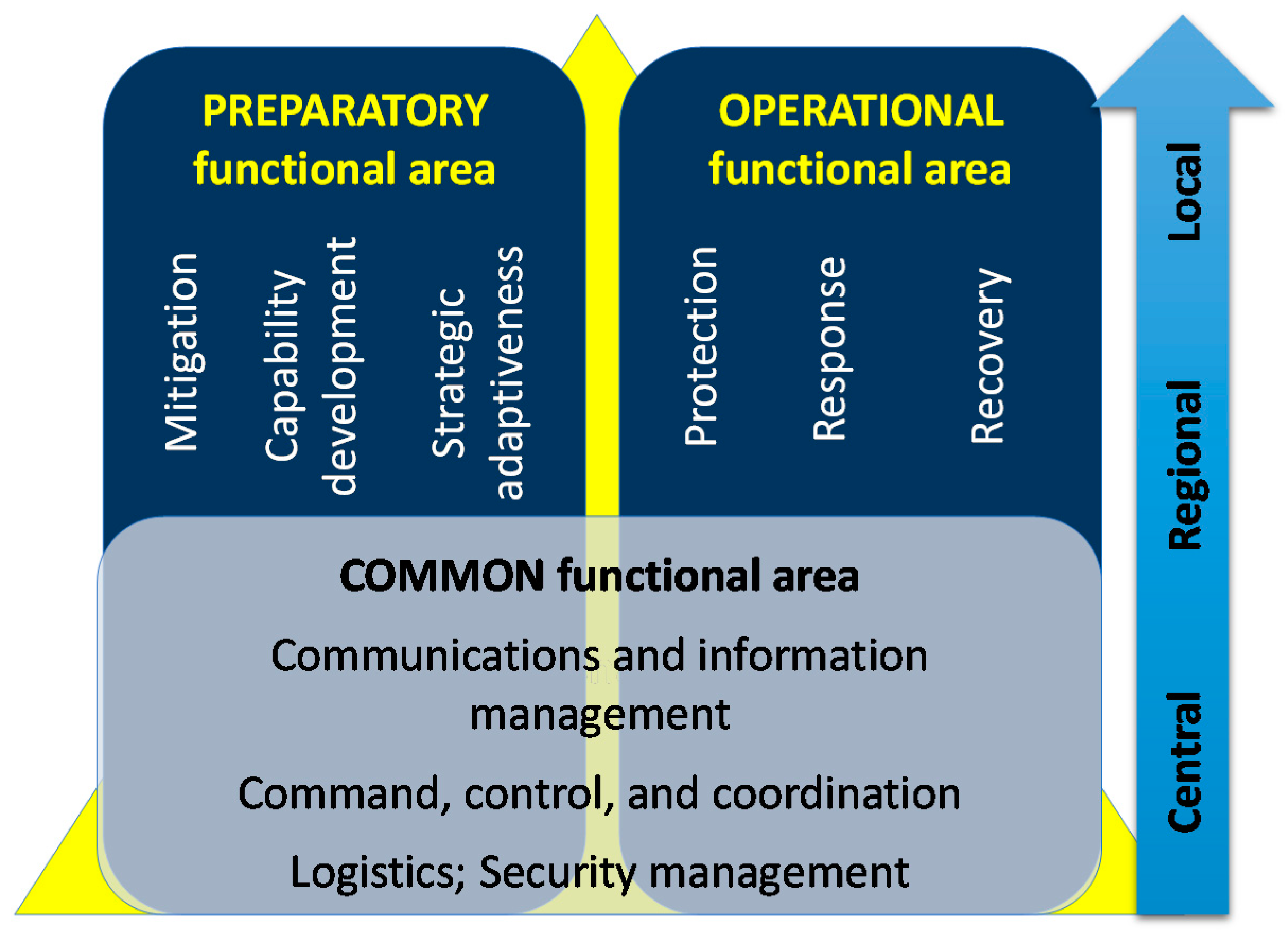

2.3.4. Multi-Dimensionality

- National (also central, federal or state) level;

- Regional (also a province, governorate or wider specific geographical area);

- Local (also community or an administrative entity at the level below province/governorate);

- Cross-border (also European or international).

2.3.5. Language

2.3.6. Commonality

2.3.7. Adaptability

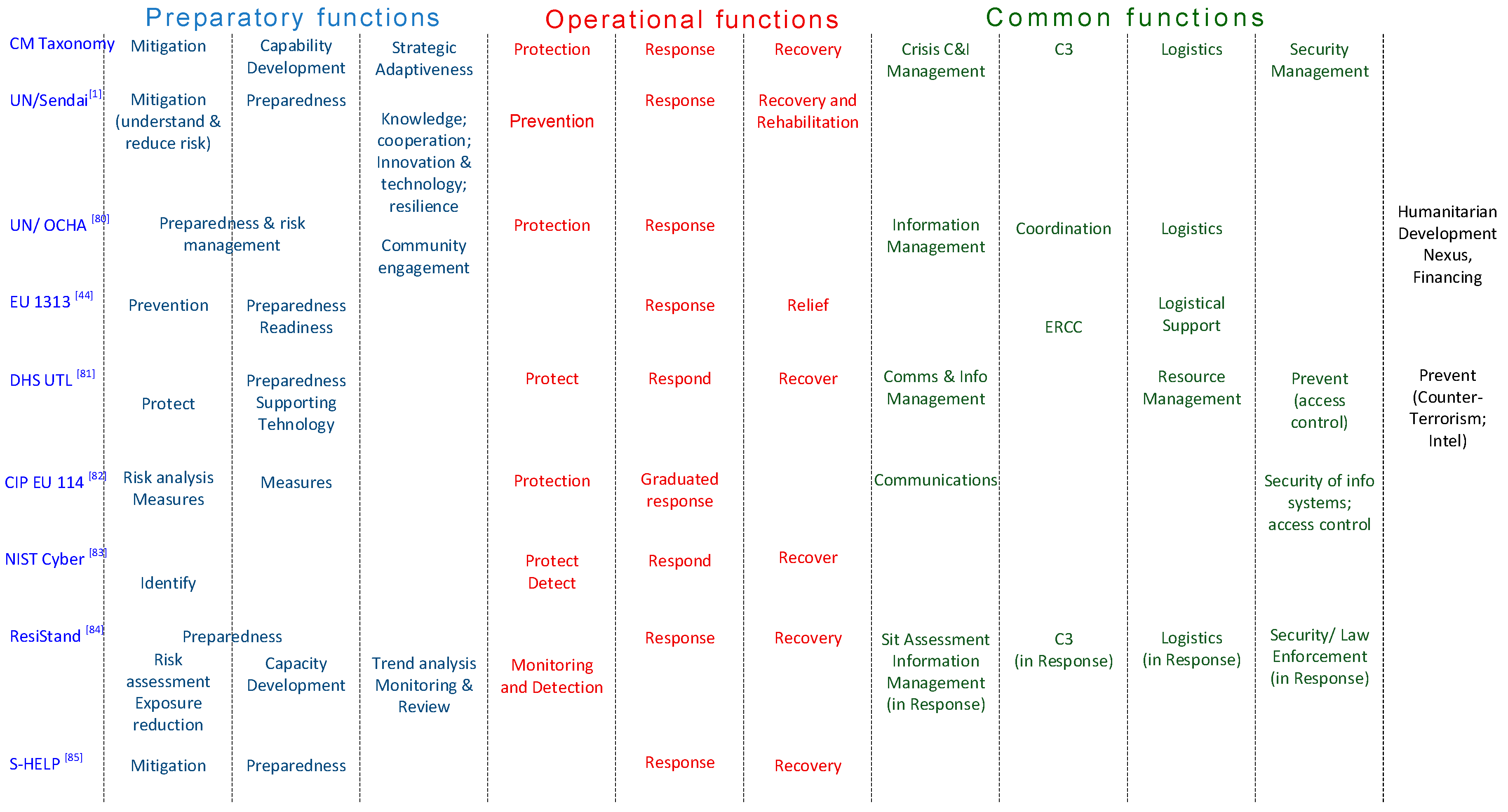

3. Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions

3.1. Preparatory Functional Areas

- Understanding disaster risk (in all its dimensions);

- Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk;

- Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience;

- Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction [1].

a state of readiness and capability of human and material means, structures, communities and organisations enabling them to ensure an effective rapid response to a disaster, obtained as a result of action taken in advance.[44]

3.1.1. Mitigation

3.1.2. Capability Development

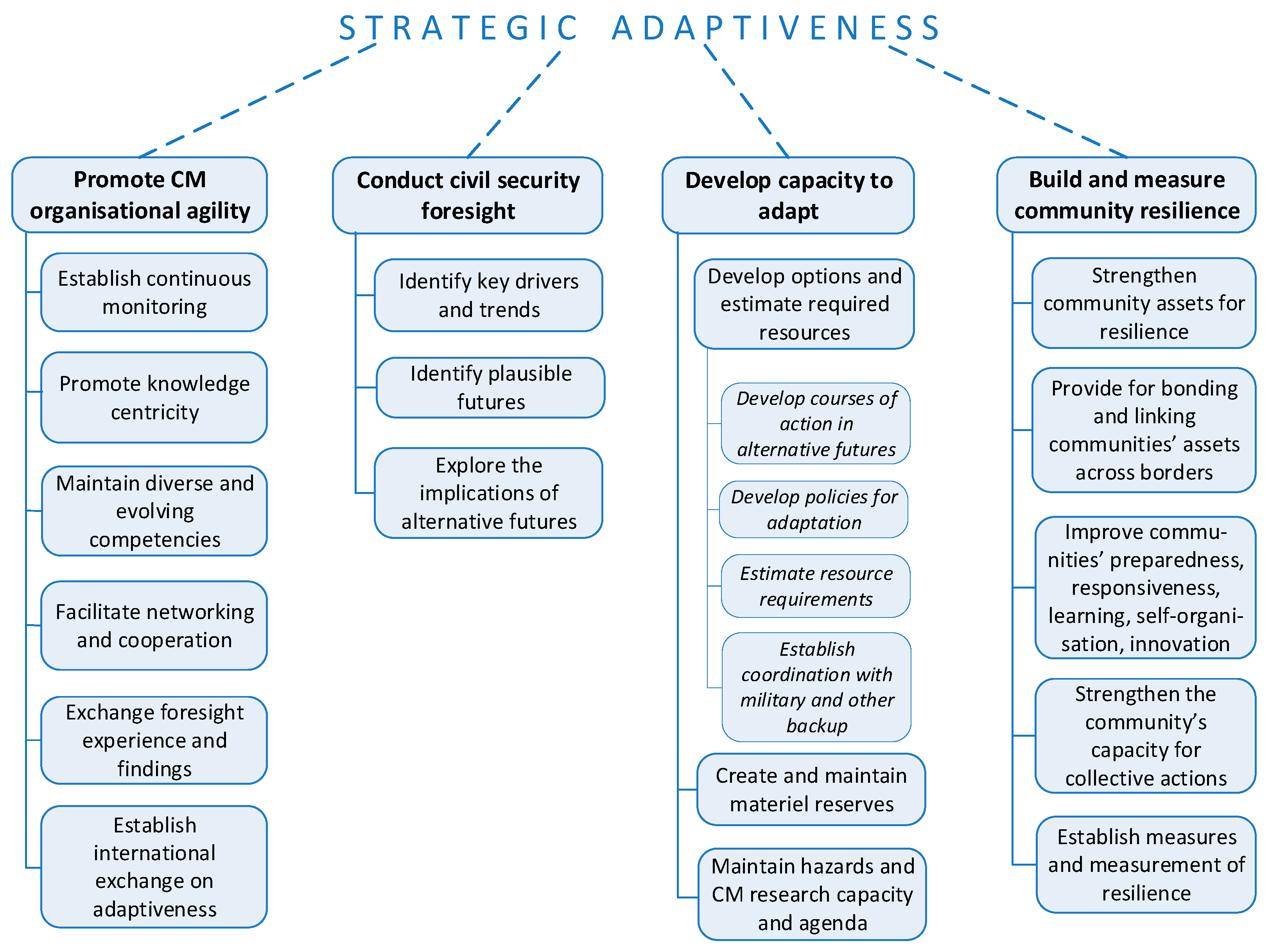

3.1.3. Strategic Adaptiveness

- Strategic adaptiveness to the ecosystem evolution may define three basic tasks: adaptation to gradual changes that may lead to the escalation of known hazards, the adaptation of measures to reduce the risk of hazards that may rise to extreme levels, and adaptation to the geospatial change of hazards towards regions, which previously have not been threatened [102];

- Strategic adaptation to changes in the societal system is much broader and entails complex structural domains as demographics, psychosocial developments, urbanisation, volunteerism, governance, and many others;

- The strategic adaptation tasks may include the reorganisation of the crisis management system towards more decentralisation or centralisation; the expansion of volunteers and public–private formats or strengthening the professional corps of responders; building an extended capacity to provide mental health and psychosocial support; the introduction of different methods of emergency sheltering; etc. Strategic adaptation to technology evolution used in crisis management may include the use of off-the-shelf assets, the adaptation of commercial or military assets to the responders’ special needs, or the design of advanced software tools and hardware.

The Union Mechanism should include a general policy framework for Union actions on disaster risk prevention, aimed at achieving a higher level of protection and resilience against disasters by preventing or reducing their effects and by fostering a culture of prevention, including due consideration of the likely impacts of climate change and the need for appropriate adaptation action.[44]

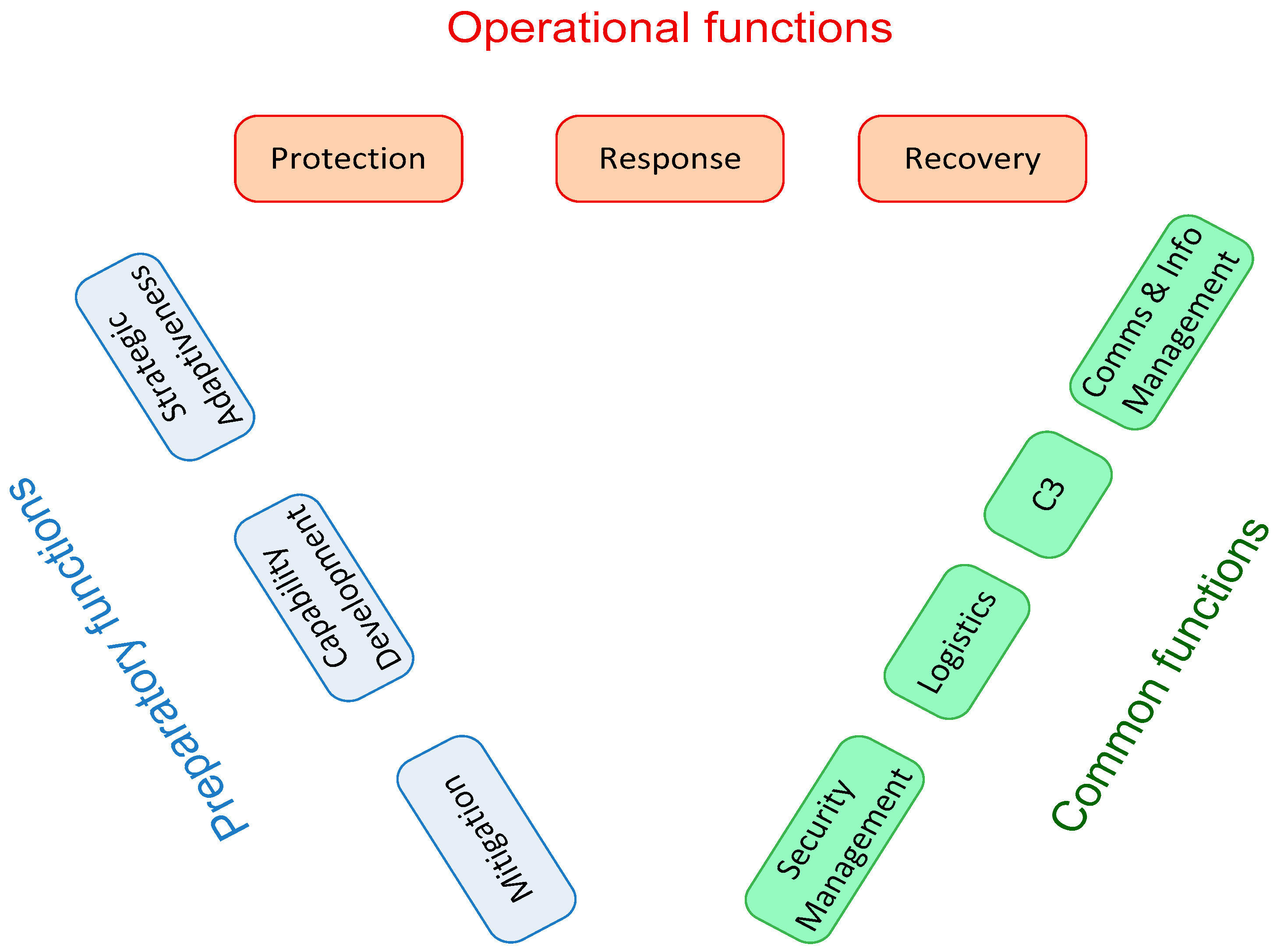

3.2. Operational Functional Areas

3.2.1. Protection

The National Protection Framework focuses on Protection core capabilities that are applicable during both steady-state conditions and the escalated decision making and enhanced Protection operations before or during an incident and in response to elevated threat. Steady-state conditions call for routine, normal, day-to-day operations. Enhanced conditions call for augmented operations that take place during temporary periods of elevated threat, heightened alert, or during periods of incident response in support of planned special events in which additional or enhanced protection activities are needed.[107]

3.2.2. Response

3.2.3. Recovery

3.3. Common Functional Areas

3.3.1. Crisis Communications and Information Management

3.3.2. Command, Control, and Coordination (C3)

3.3.3. Logistics

Logistics integrates whole community logistics incident planning and support for timely and efficient delivery of supplies, equipment, services, and facilities. It also facilitates comprehensive logistics planning, technical assistance, training, education, exercise, incident response, and sustainment that leverage the capability and resources of Federal logistics partners, public and private stakeholders, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in support of both responders and disaster survivors.[111] (p. 1)

3.3.4. Security Management

4. Taxonomy Evolution, Current and Future Use

- Analyse and account for the experience in the use of the taxonomy in classifying crisis management gaps and solutions on the Portfolio of Solutions (POS) platform;

- Provide for a classification of new solutions and authoritative lists of crisis management gaps and effective association of gaps and solutions;

- Expand the taxonomy to allow for a classification of gaps and solutions related to terrorist acts, chemical, biological and radiological threats and the increasing reliance of both society and crisis management organisations on information and communications infrastructures, i.e., on cyberspace.

- “Common Global Capability Gaps” identified by the International Forum to Advance First Responder Innovation (IFAFRI), https://www.internationalresponderforum.org/resources; and

- ‘strategic gaps’ and the challenges, policies, and recommendations elaborated by the EU DRMKC’s (Disaster Risk Management Knowledge Centre) “Gaps Explorer” in a pilot project on forest fires, https://drmkc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/knowledge/Gaps-Explorer/forest-Fires.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. In Proceedings of the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai, Japan, 14–18 March 2015; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Uwizera, C. Sustainable Development: International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, A/70/472/Add.3. UN General Assembly. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/472/Add.3&Lang=E (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- European Commission. Action Plan on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. A Disaster Risk-Informed Approach for All EU Policies. SWD(2016) 205 Final/2. Brussels. 17 June 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/sites/echo-site/files/1_en_document_travail_service_part1_v2.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Eller, W.S.; Wandt, A.S. Contemporary policy challenges in protecting the homeland. Policy Stud. J. 2020, 48, S33–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paté-Cornell, M.-E.; Kuypers, M.; Smith, M.; Keller, P. Cyber risk management for critical infrastructure: A risk analysis model and three case studies. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pescaroli, G.; Wicks, R.T.; Giacomello, G.; Alexander, D.E. Increasing Resilience to Cascading Events: The M.OR.D.OR. Scenario. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Fattoum, A.; Moreno, J.; Bealt, J. A Structured Methodology to peer review disaster risk reduction activities: The viable system review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 46, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.P.; Torres-Muñoz, A.M. Risk transfer for populations in precarious urban environments. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Li, W.-S. Public private partnership operational model—A conceptual study on implementing scientific-evidence-based integrated risk management at regional level. J. Disaster Res. 2019, 14, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, E.; Mysiak, J.; Oliveira, C.S.; Peters, K.; Surminski, S. Managing disaster risk. In Science for Disaster Risk Management 2017: Knowing Better and Losing Less; Poljanšek, K., Ferrer, M.F., De Groeve, T., Clark, I., Eds.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 442–515. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, L.; Fleming, K.; Abad, J.; Schueller, L.A.; Leone, M.; Scolobig, A.; Baills, A. simulating synergies between climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction stakeholders to improve management of transboundary disasters in Europe. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, G. What makes climate change adaptation effective? A systematic review of the literature. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 62, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, O.; Tomov, N.; Nikolova, I. M&S Support for crisis and disaster management processes and climate change implications. In Information Technology in Disaster Risk Reduction; Murayama, Y., Velev, D., Zlateva, P., Gonzalez, J.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Foks-Ryznar, A.; Ryzenko, J.; Trzebińska, K.; Tymińska, J.; Wrzosek, E.; Zwęgliński, T. Trial as a pragmatic and systematic approach for assessing new solutions in crisis management and rescue operations. In Proceedings of the XLIV-th IEEE-SPIE Joint Symposium, Wilga, Poland, 6 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Pan-European Test-bed for Crisis Management Capability Building, DRIVER+. Available online: https://www.driver-project.eu/a-pan-european-test-bed-for-crisis-management-capability-building/ (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Goel, K. Understanding community and community development. In Community Work: Theories, Experiences and Challenges; Goel, K., Pulla, V., Francis, A.P., Eds.; Niruta Publications: Bangalore, India, 2014; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chandra, C.; Shiau, J.-Y. Developing taxonomy and model for security centric supply chain management. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2009, 17, 184–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, B. Organizational Systematics—Taxonomy, Evolution, Classification; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Knezić, S.; Baučić, M.; Kekez, T.; Delprato, U.; Tusa, G.; Preinerstorfer, A.; Lichtenegger, G. Taxonomy for Disaster Response: A Methodological Approach. In Proceedings of the TIEMS 2015 Annual Conference, Rome, Italy, 30 September–2 October 2015; Available online: https://episecc.eu/sites/default/files/TIEMS_2015_AC_submission_21.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Ontology Model for the EPISECC Use Case, Deliverable D4.4. EPISECC Project. 2015. Available online: https://episecc.eu/sites/default/files/EPISECC_WP4_D4%204_Deliverable_Report.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Sveinsdottir, T.; Finn, R.; Rodrigues, R.; Wadhwa, K.; Fritz, F.; Kreissl, R.; von Laufenberg, R.; de Hert, P.; Tanas, A.; van Brakel, R. Taxonomy of Security Products, Systems and Services, Deliverable D1.2. CRISP Project. 2016. Available online: https://www.trilateralresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CRISP-D1.2-Taxonomy-of-Security-Products-Systems-Services_REVISED.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Liu, S.; Brewster, C.; Shaw, D. Ontologies for Crisis Management: A Review of State of the Art in Ontology Design and Usability. In Proceedings of the 10th International ISCRAM Conference, Baden-Baden, Germany, 12–15 May 2013; Comes, T., Fiedrich, F., Fortier, S., Geldermann, J., Yang, L., Eds.; ISCRAM Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; pp. 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Information and Documentation—Records Management—Part 1: Concepts and Principles; ISO 15489-1:2016; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Canton, L.G. Emergency Management: Concepts and Strategies for Effective Programs; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. Just as a disaster is not simply a big incident, so a catastrophe is not just a big disaster. J. Am. Soc. Prof. Emerg. Plan. 1996, 3, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Societal Security—Terminology; ISO 22300:2012; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNISDR. Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, P. Hazard as a Concept; Safety Institute of Australia: Tullamarine, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Overview of Natural and Man-Made Disaster Risks in the EU; Commission Staff Working Paper SWD/2014/0134 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, I.; Kates, R.; White, G. The Environment as Hazard; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. (Ed.) What Is A Disaster? Perspectives on the Question; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter, S.L. (Ed.) American Hazardscapes: The Regionalization of Hazards & Disasters in the United States; Joseph Henry Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bokwa, A. Föhn. In Encyclopedia of Natural Hazards; Bobrowsky, P.T., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security. DHS Risk Lexicon; Department of Homeland Security: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Cutter, S.L. Living with Risk; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Weichselgartner, J. Disaster mitigation: The concept of vulnerability revisited. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2001, 10, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques; IEC 31010:2019; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Public Safety Canada. All Hazards Risk Assessment Methodology Guidelines 2012–2013; Public Safety Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012.

- World Health Organisation. Concepts in Emergency Management: The Basis of EHA Training Programmes in WPRO. Available online: https://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/tools/WHO_strategy_consecpts_in_emegency_management.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Department of Homeland Security. National Response Framework, 3rd ed.; DHS: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Ife, J.W. Community Development: Creating Community Alternatives—Vision, Analysis and Practice; Longman: Melbourne, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shaluf, I.M.; Ahmadun, F.-R.; Said, A.M. A review of disaster and crisis. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2003, 12, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Bhopal: Anatomy of Crisis, 2nd ed.; Ballinger: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and the Council. Decision No 1313/2013/EU of the european parliament and of the council on a union civil protection mechanism. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 347, 924–947. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2013/1313/oj (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- European Commission. Risk Assessment and Mapping Guidelines for Disaster Management; Commission Staff Working Paper, SEC(2010)1626 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, W. Guide to Emergency Management and Related Terms, Definitions, Concepts, Acronyms, Organizations, Programs, Guidance, Executive Orders & Legislation: A Tutorial on Emergency Management, Broadly Defined, Past and Present; Department of Homeland Security: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Department of Homeland Security. Pandemic Influenza Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Guide for Critical Infrastructure and Key Resources; DHS: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Quarantelli, E.L. Catastrophes are Different from Disasters: Some Implications for Crisis Planning and Managing Drawn from Katrina; Disaster Research Center, University of Delaware: Newark, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. Emergency Preparedness and Response—Some Issues and Challenges Associated with Major Emergency Incidents (William O. Jenkins, Jr. Testimony before the Little Hoover Commission); GAO: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Rood, J. Medical Catastrophe—No One’s in Charge, the Plan’s Incomplete and Resources Aren’t Sufficient if We Suffer Mass Casualties in an Overwhelming Disaster. Available online: https://www.govexec.com/magazine/features/2005/11/medical-catastrophe/20591/ (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Kastrioti, C. USA: Katrina—Managing a Catastrophe; Institute for Crisis, Disaster, and Risk Management: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/united-states-america/usa-katrina-managing-catastrophe (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Van Wart, M.; Kapucu, N. Crisis management competencies: The case of emergency managers in the USA. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazmand, A. Introduction—Crisis and Emergency Management. In Handbook of Crisis and Emergency Management; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA; Basel, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Societal Security—Guideline for Incident Preparedness and Operational Continuity Management; ISO/PAS 22399:2007; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Skertchly, A.; Skertchly, K. Catastrophe management: Coping with totally unexpected extreme disasters. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2001, 16, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Qihao, H. Climate Change and Catastrophe Management in a Changing China; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C. Is Your Business Protected? Manag. Rev. 1995, 84, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, C.F. Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1963, 81, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, U.; Kouzmin, A. Crises and Crisis Management: Toward Comprehensive Government Decision Making; Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wittacker, H. State Comprehensive Emergency Management; Defense Civil Preparedness Agency: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1979.

- Petiet, P.; van Berlo, M.; Weggemans, A.; Tymkiw, C.; Albièro, S.; Bergersen, S.; Gala, F.; Stelkens-Kobsch, T. Updated Project Handbook; Deliverable D911.10. DRIVER+ Project; The Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research: Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, W.L.; Streib, G. Collaboration and leadership for effective emergency management. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, C. Organizing for homeland security after katrina: Is adaptive management what’s missing? Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D. From civil defence to civil protection—And back again. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2002, 11, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratchev, V.; Tagarev, T. Policy and legal frameworks of using armed forces for domestic disaster response and relief. Inf. Secur. Int. J. 2018, 40, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The EU Internal Security Strategy in Action: Five Steps towards a More Secure Europe, COM/2010/0673 Final. 2010. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52010DC0673 (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Löscher, M.; Woitsch, P.; van Zetten, J.; Stolk, D.; van der Lee, M.; Bousché, H.; Vollmer, M.; Pastuszka, H.-M.; Heikkilä, A.-M.; Fuggini, C.; et al. ResiStand Handbook; Deliverable D1.1. ResiStand Project; GEOWISE: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Governors’ Association. Comprehensive Emergency Management: A Governor’s Guide; Center for Policy Research: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A.; ‘T Hart, P.; Stern, E.; Sundelius, B. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership Under Pressure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, D. Reconsidering the Phases of Disaster. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 1997, 17, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, A.D.; Smith, B. Defining ‘Function’. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Definitions in Ontologies IWOOD 2015, Lisbon, Portugal, 27–30 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The US Department of Defense. DoD Architecture Framework Version 2.02, DoD Data Model; The US Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Bountouri, L.; Papatheodorou, C.; Gergatsoulis, M. Modelling the public sector information through CIDOC conceptual reference model. In On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM 2010 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Meersman, R., Dillon, T., Herrero, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 6428, pp. 404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.M.; Mitroff, I.I. From Crisis Prone to Crisis Prepared: A Framework for Crisis Management. Acad. Manag. 1993, 7, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolk, D.; Beerens, R.; de Groeve, T.; Hap, B.; Kudrlova, M.; Kyriazanos, D.; Langinvainio, M.; van der Lee, M.; Missoweit, M.; Pastuszka, H.-M.; et al. Aftermath Crisis Management—Approaches and Solutions; Deliverable D5.1. ACRIMAS Project; Fraunhofer Institute for Technological Trend Analysis: Euskirchen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fayol, H. General and Industrial Management; Pitman: London, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, J. The Essence of Winning & Losing, Unpublished manuscript. 1995.

- McKay, B.; McKay, K. The Tao of Boyd: How to Master the OODA Loop. The Art of Manliness, Last Updated: 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.artofmanliness.com/articles/ooda-loop/ (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Civil Contingencies Secretariat. HM Government Emergency Response and Recovery: Non Statutory Guidance Accompanying the Civil; Contingencies Act. 2004; The UK Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2013.

- United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Themes. Available online: https://www.unocha.org/themes (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Department of Homeland Security. Universal Task List: Version 2.1; DHS: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=458805 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- European Council. Council Directive 2008/114/EC of 8 December 2008 on the Identification and Designation of European Critical Infrastructures and the Assessment of the Need to Improve Their Protection. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 345, 75–82. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/114/oj (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- National Institute for Standards and Technology. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity; v.1.1.; Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Stolk, D.; van der Lee, M.; Petiet, P.; Liedtke, C.; Lindner, R.; van Zetten, J.; Karppinen, A.; Anson, S.; Kroen, I. Assessment Framework for Standardisation Activities; Deliverable 1.3. ResiStand Project; TNO: Rijswijk, The Netherlands, January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, K.; O’Riordan, S.; Pope, A.; Rauner, M.; Rochford, M.; Madden, M.; Sweeney, J.; Nussbaumer, A.; McCarthy, N.; O.‘Brien, C. Towards the development of a decision support system for multi-agency decision-making during cross-border emergencies. J. Decis. Syst. 2016, 25 (Suppl. 1), 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Societal Security—Preparedness and Continuity Management Systems—Requirements; ISO 22301:2012; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. What Is Mitigation? FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/what-mitigation (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- International Organization for Standardization. Societal Security—Emergency Management—Requirements for Incident Response; ISO 22320:2011; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines; ISO 31000:2009; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tagarev, T. The art of shaping defense policy: Scope, components, relationships (but no Algorithms). Connect. Q. J. 2006, 5, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.K. Analytic Architecture for Capabilities-Based Planning, Mission-System Analysis, and Transformation; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. Societal Security—Mass Evacuation—Guidelines for Planning; ISO 22315:2014; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, B.E. (Ed.) Handbook on Long Term Defence Planning; NATO Research and Technology Agency: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. (Ed.) Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, H.M.; Colyvan, M.; Burgman, M.A. A taxonomy and treatment of uncertainty for ecology and conservation biology. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Peat, F.D. From Certainty to Uncertainty: The Story of Science and Ideas in the Twentieth Century; Joseph Henry Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Adaptive Management for Water Resources Project Planning; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Star, J.; Rowland, E.L.; Black, M.E.; Enquist, C.A.; Garfin, G.; Hoffman, C.H.; Hartmann, H.; Jacobs, K.L.; Moss, R.H.; Waple, A.M. Supporting adaptation decisions through scenario planning: Enabling the effective use of multiple methods. Clim. Risk Manag. 2016, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garard, J.; Luers, A.; Star, J.; Laubacher, R.; Cronin, C. Broadening the Dialogue: Exploring Alternative Futures to Inform Climate Action, Futures CoLab. November 2018. Available online: https://futureearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Broadening-the-Dialogue-Futures-CoLab-20.11.2018.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Gambhir, A.; Cronin, C.; Matsumae, E.; Rogelj, J.; Workman, M. Using Futures Analysis to Develop Resilient Climate Change Mitigation Strategies; Grantham Institute Briefing Paper No. 33; Imperial College London: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.climateworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Grantham-Briefing-Paper-33-Futures-Analysis-for-Climate-Mitigation.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- German Committee for Disaster Reduction. Enhancing Methods and Tools of Disaster Risk Reduction in the Light of Climate Change; DKKV: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, A.; Bennet, D. Organizational Survival in the New World: The Intelligent Complex; Adaptive System; KMCI Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Casciano, D. COVID-19, Discipline and blame: From italy with a call for alternative futures. J. Extrem. Anthropol. 2020, 4, E18–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meriläinen, E. The dual discourse of urban resilience: Robust city and self-organised neighbourhoods. Disasters 2020, 44, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockenschaub, G. Strengthening Health Systems Crisis Management Capacities in the WHO European Region; A WHO—DG Sanco Collaboration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Homeland Security. National Protection Framework, 2nd ed.; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Christensen, T.; Lægreid, P.; Rykkja, L.H. Crisis management organization: Building governance capacity and legitimacy. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Publication 1 (Capstone Doctrine); FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 42–44.

- Penuel, K.B.; Statler, M.; Hagen, R. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Crisis Management; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. Emergency Support: Function # 7—Logistics Annex; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Clémenceau, A.; Giroud, F.; Ryzenko, J.; Wrzozek, E.; Loescher, M.; Albiéro, S.; Atun, F.; Fonio, C.; Tagarev, T.; Bird, M.; et al. List of Crisis Management Gaps; Deliverable D922.11. DRIVER+ Project; The Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research: Delft, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, P.; Moore, S. Responding to the Cyber Threat: A UK Military Perspective. Connect. Q. J. 2020, 19, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinhos, L. Cyber defence in Germany: Challenges and the way forward for the bundeswehr. Connect. Q. J. 2020, 19, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergersen, S.; Martins, B.O.; Hermansen, E. Societal Impact Assessment Framework—Version 2; Deliverable D913.31. DRIVER+ Project; The Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research: Delft, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen, S.; Palacio, C.; Reuge, E.; Philpot, J.; Martins, B.O.; Hermansen, E. A Guide on Assessing Unintended Societal Impacts of Different CM Functions—Version 2; Deliverable D913.41. DRIVER+ Project; The Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research: Delft, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sliuzas, R.; Jackovics, P.; Thorvaldsdóttir, S.; Kalinowska, K.; Tyrologou, P.; Resch, C.; Castellari, S.; Greiving, S. Risk Management Planning. In Science for DRM 2020: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tagarev, T.; Ratchev, V. A Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125147

Tagarev T, Ratchev V. A Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125147

Chicago/Turabian StyleTagarev, Todor, and Valeri Ratchev. 2020. "A Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125147

APA StyleTagarev, T., & Ratchev, V. (2020). A Taxonomy of Crisis Management Functions. Sustainability, 12(12), 5147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125147