Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customers of Fitness Centers

2.2. Managers of Fitness Centers

2.3. Best Practices in Fitness Centers

2.4. Qualitative Research in Sport

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

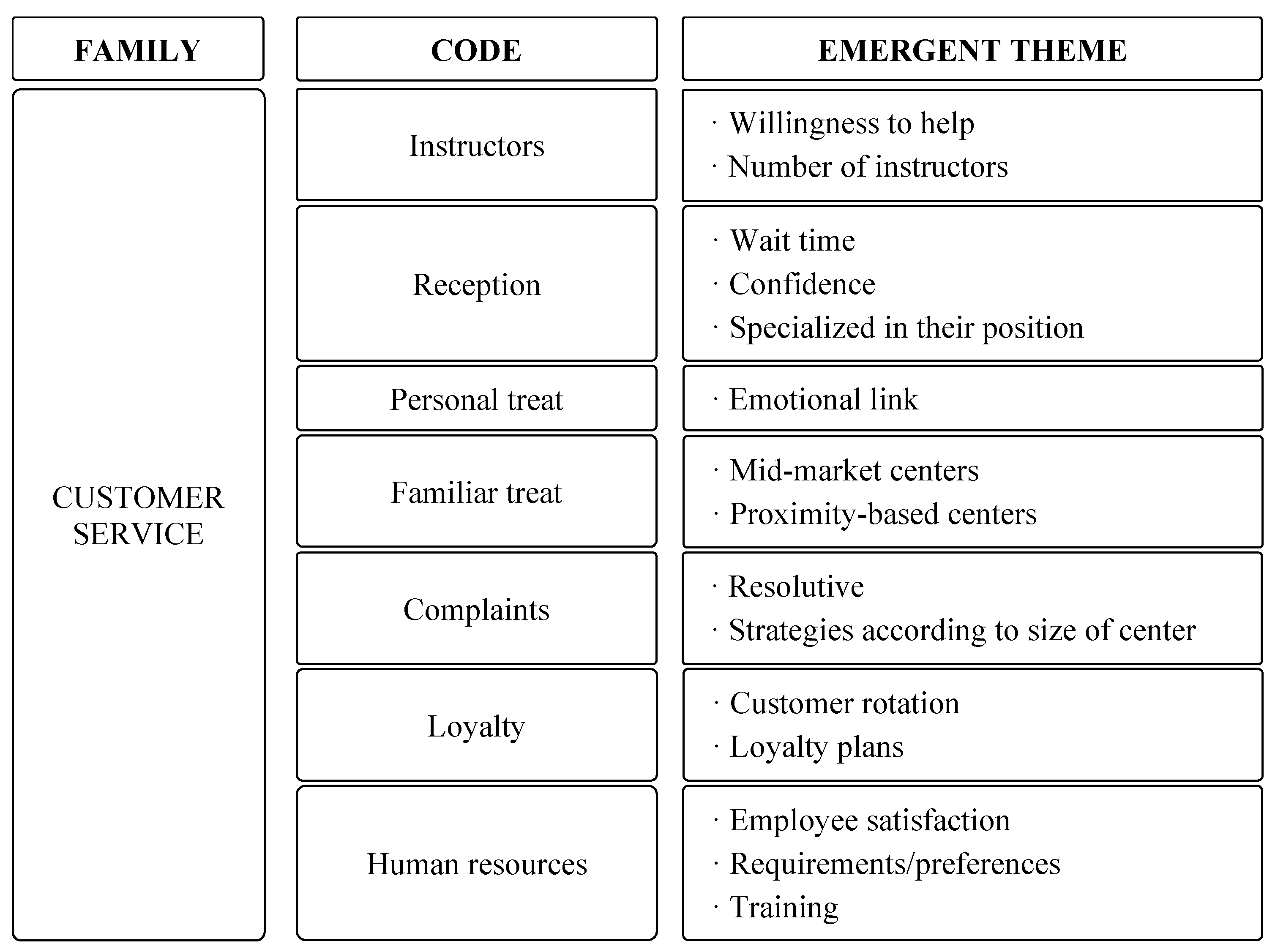

- Customer service: the set of strategies developed by fitness centers through their employees to optimize the interaction with users.

- Offered service: including the core services, basic sports services that are fundamental for the business, and supplementary services, not essential, but adding value to the core service.

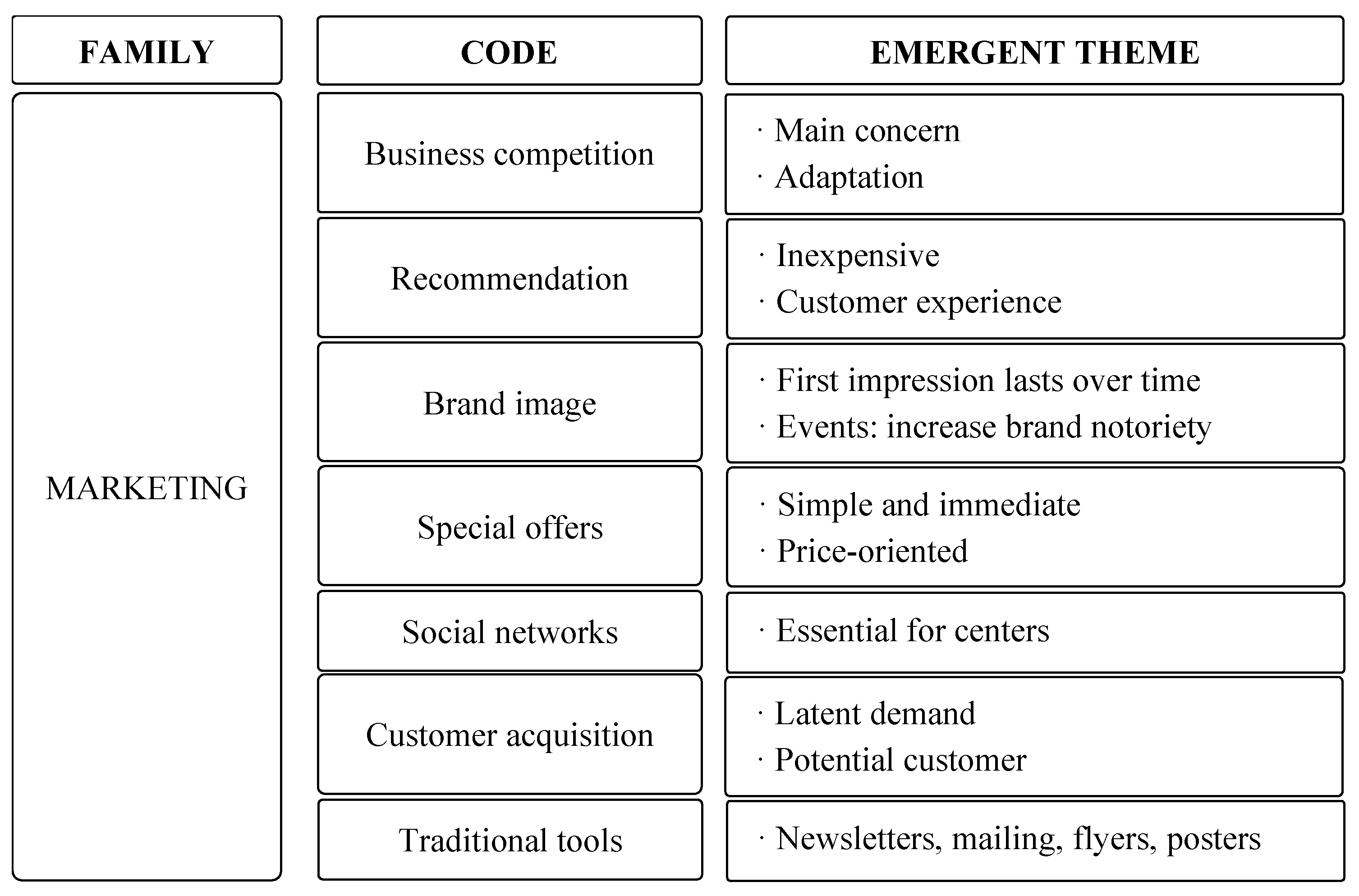

- Marketing: regarding the strategies and tools used by fitness centers for acquiring or retaining customers.

- Facilities: the physical environment where the activity of the fitness centers is developed, whether intended for sports activities or not.

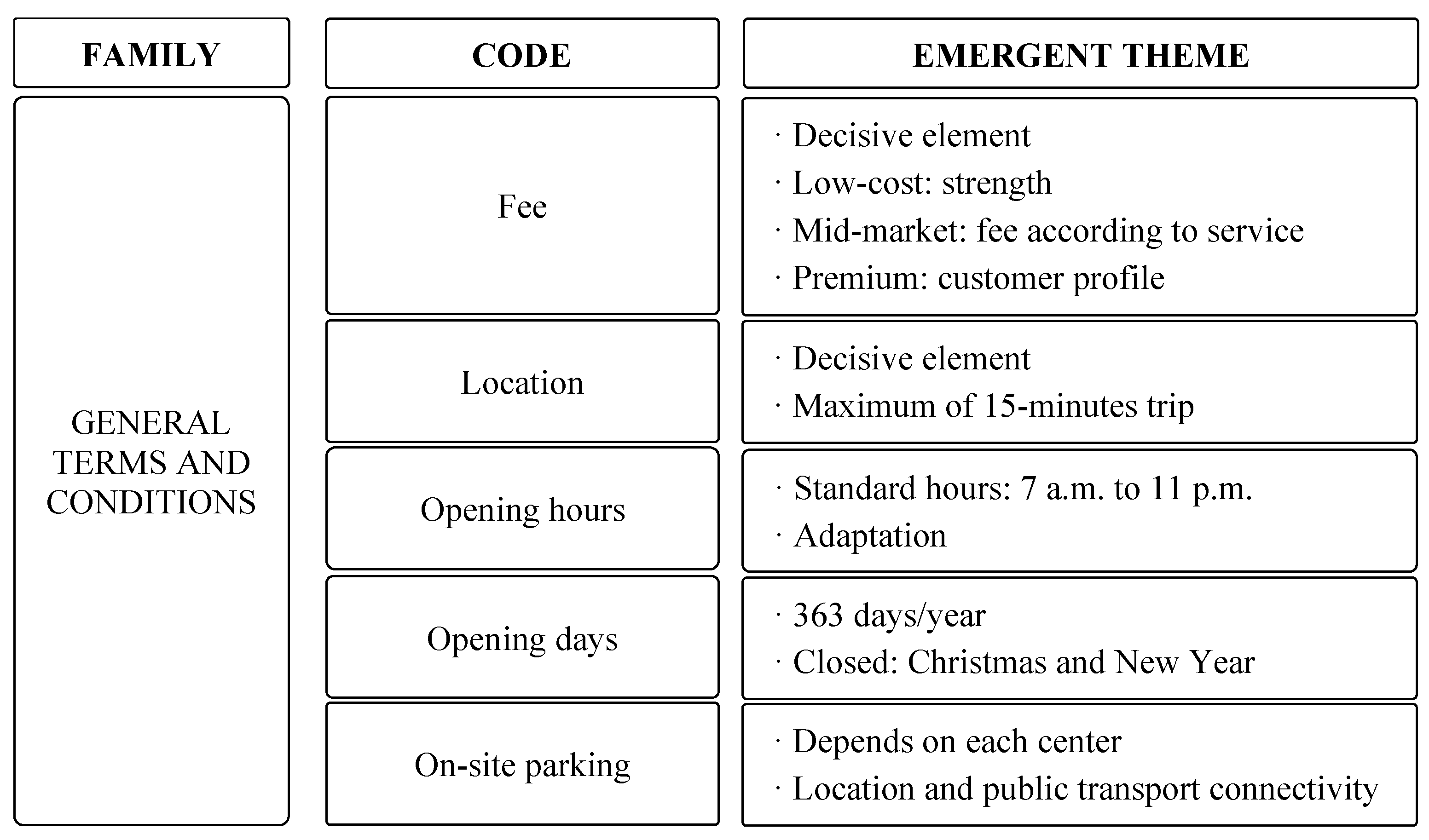

- General terms and conditions: requirements or clauses accepted by the customer during his membership.

4.1. Customer Service

4.2. Offered Service

4.3. Marketing

4.4. Facilities

4.5. General Terms and Conditions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association. The 2019 IHRSA Global Report; IHRSA: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Europe Active. European Health Fitness Market Report 2020; Europe Active: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, R.; Woo, M. Determinants of Perceived Service Quality: An Empirical Investigation of Fitness and Recreational Facilities. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2016, 12, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clavel, I.; García-Unanue, J.; Iglesias-Soler, E.; Felipe, J.L.; Gallardo, L. Prediction of abandonment in Spanish fitness centres. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 19, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Arroyo, M.J.; García-Fernández, J.; Gálvez-Ruiz, P.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M. Analyzing Consumer Loyalty through Service Experience and Service Convenience: Differences between Instructor Fitness Classes and Virtual Fitness Classes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J.; Gálvez-Ruíz, P.; Fernández-Gavira, J.; Vélez-Colón, L.; Pitts, B.; Bernal-García, A. The effects of service convenience and perceived quality on perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty in low-cost fitness centers. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H.W.; Craig, C.L.; Lambert, E.V.; Inoue, S.; Alkandari, J.R.; Leetongin, G.; Kahlmeier, S.; Andersen, L.B.; Bauman, A.E.; Blair, S.N.; et al. The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. Lancet 2012, 380, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Special Eurobarometer 472 Report—Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9a69f642-fcf6-11e8-a96d-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Thompson, W.R. Worldwide Survey of Fitness Trends for 2020. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2019, 23, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakoulis, A. European Survey of Fitness Trends for 2020. ACSMs Health Fit. J. 2019, 23, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A Dynamic Process Model of Service Quality: From Expectations to Behavioral Intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, M.A.; Palmer, A. Importance-performance analysis: A useful tool for directing continuous quality improvement in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2004, 12, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E.; Tzetzis, G.; Konsoulas, D. Perceived Service Quality and Loyalty of Fitness Centers’ Customers: Segmenting Members Through Their Exercise Motives. Serv. Mark. Q. 2017, 38, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voráček, J.; Čáslavová, E.; Šíma, J. Segmentation in sport services: A typology of fitness customers. Acta Univ. Carol. Kinanthropol. 2016, 51, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- León-Quismondo, J.; García-Unanue, J.; Burillo, P. Service Perceptions in Fitness Centers: IPA Approach by Gender and Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burillo, P.; Sánchez-Fernández, P.; Dorado, A.; Gallardo, L. Global customer satisfaction and its components in local sports services. A discrimminat analysis. J. Sports Econ. Manag. 2012, 2, 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorakis, N.; Alexandris, K.; Rodriguez, P.; Sarmento, P.J. Measuring customer satisfaction in the context of health clubs in Portugal. Int. Sports J. 2004, 8, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitskari, E.; Quick, S.; Tsakiraki, A. Measuring Exercise Involvement Among Fitness Centers’ Members: Is It Related With Their Satisfaction? Serv. Mark. Q. 2014, 35, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandris, K.; Zahariadis, P.; Tsorbatzoudis, C.; Grouios, G. An empirical investigation of the relationships among service quality, customer satisfaction and psychological commitment in a health club context. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2004, 4, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrosen, S.; Lagrosen, Y. Exploring service quality in the health and fitness industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2007, 17, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakova, O.; Mirza, M.T. Service quality models in the context of the fitness industry. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 6, 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabuig, F.; Quintanilla, I.; Mundina, J. La calidad percibida de los servicios deportivos: Diferencias según instalación, género, edad y tipo de usuario en servicios náuticos. RYCIDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2008, 4, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.M. An importance-performance analysis of fitness center service quality: Empirical results from fitness centers in Turkey. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 7031–7041. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Rodriguez, A.; Onetti-Onetti, W.; Chinchilla-Minguet, J.L. Perceived Quality in Sports Centers in Southern Spain: A Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avourdiadou, S.; Theodorakis, N.D. The development of loyalty among novice and experienced customers of sport and fitness centres. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; De Ruyter, K. Customer loyalty in high and low involvement service settings: The moderating impact of positive emotions. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandei, S.; Vieira, M.C.; Reis, A.C. Adherence to physical activity in an unsupervised setting: Explanatory variables for high attrition rates among fitness center members. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavel, I.; García-Unanue, J.; Iglesias-Soler, E.; Gallardo, L.; Felipe, J.L. Drop out prediction in sport centres. Definition of models and reproducibility. Retos 2020, 37, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Açak, M. An examination of the decision-making styles of hearing-impaired sports club managers in Turkey. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 8309–8319. [Google Scholar]

- Çiftçi, S.; Gökçel, B.; Demirkıran, Y. Analyse of the Expectations of the Sports Management Students in Terms of Quality. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 2602–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranco, D.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Crovetto, M.; Barbado, C.; Boned, C.; Felipe, J.L. Differences in Conditions of Employment Between Sport Managers With and Without a Degree in Physical Activity and Sport Sciences. J. Sport Health Res. 2015, 7, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, L.M.; Henry, I.; Chin Hsun, J. The perceived importance of sport management competencies by academics and practitioners in the cultural/industrial context of Taiwan. Manag. Leis. 2011, 16, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retar, I.; Plevnik, M.; Kolar, E. Key competences of Slovenian sport managers. Ann. Kinesiol. 2013, 4, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Koustelios, A. Identifying important management competencies in fitness centres in Greece. Manag. Leis. 2003, 8, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelladurai, P. Sport Management: Macro Perspectives; Sports Dynamics: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, M.; Edwards, J.; Washington, M. Understanding the concept of professionalisation in sport management research. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boned, C.J.; Felipe, J.L.; Barranco, D.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M.; Crovetto, M. Perfil profesional de los trabajadores de los centros de fitness en España. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2015, 15, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Mischler, S.; Bauger, P.; Pichot, L.; Wipf, E. Private fitness centres in France: From organisational and market characteristics to micromentalities of the managers. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2009, 5, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J.; Bernal-García, A.; Fernández-Gavira, J.; Vélez-Colón, L. Analysis of existing literature on management and marketing of the fitness centre industry. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2014, 36, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G.B. Theory and theory development in sport management. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, N.; Kaburakis, A. Bridging the Gap: U.S. Sport Managers on Barriers to Industry–Academia Research Collaboration. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmus, M.; Kubina, M.; Koman, G.; Ferenc, P. Ensuring the Long-Term Sustainability Cooperation with Stakeholders of Sports Organizations in SLOVAKIA. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.L.P.; Lacerda, T.S. Fitness centers: What are the most important attributes in this sector? Int. J. Qual. Res. 2019, 13, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.; Ferreira, J.J. Strategic framework of fitness clubs based on quality dimensions: The blue ocean strategy approach. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2017, 29, 1648–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Felipe, J.L.; Gallardo, L.; Burillo, P.; Gallardo, A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Plaza-Carmona, M. A qualitative vision of artificial turf football fields: Elite players and coaches. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2013, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; Gallardo, L.; Ubago-Guisado, E.; García-Unanue, J.; Felipe, J.L. Causes of customer dropouts in fitness and wellness centres: A qualitative analysis. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2018, 40, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. The Significance of Saturation. Qualitative Health Research. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, N.; Soriano, C.; López, A.; Rosa, D.; Magraner, L.; Porcar, R.M.; Such, M.J.; Sánchez, J.J.; Prat, J.M. Factores de Éxito Desde la Perspectiva del Usuario en Instalaciones Deportivas, de ocio y Salud en Comunidad Valenciana; Instituto de Biomecánica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elasri, A.; Triadó, X.M.; Aparicio, P. La satisfacción de los clientes de los centros deportivos municipales de Barcelona. Apunt. Educ. Física Deporte 2015, 119, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuviala, A.; Grao-Cruces, A.; Tamayo, J.A.; Nuviala, R.; Álvarez, J.; Fernández-Martínez, A. Diseño y análisis del cuestionario de valoración de servicios deportivos (EPOD2). Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2013, 13, 419–436. [Google Scholar]

- Rial, A.; Rial, J.; Varela, J.; Real, E. An application of importance-performance analysis (IPA) to the management of sport centres. Manag. Leis. 2008, 13, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J. Business & Fitness. El Negocio de los Centros Deportivos; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dhurup, M.; Singh, P.C.; Surujlal, J. Customer service quality at commercial health and fitness centres. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2006, 28, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, G.; Dale, L.P.; Lau, E. Examining the use of loyalty point incentives to encourage health and fitness centre participation. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afthinos, Y.; Theodorakis, N.D.; Nassis, P. Customers’ expectations of service in Greek fitness centers. Gender, age, type of sport center, and motivation differences. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2005, 15, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, J.; Fernández-Gavira, J.; Durán-Muñoz, J.; Vélez-Colón, L. La actividad en las redes sociales: Un estudio de caso en la industria del fitness. Retos 2015, 28, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.; Chinn, S.J. Meeting Relationship-Marketing Goals Through Social Media: A Conceptual Model for Sport Marketers. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2010, 3, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, R.F. The Impact of Experimental Marketing on Customer Loyalty for Fitness Clubs: Using Brand Image and Satisfaction as the Mediating Variables. J. Int. Manag. Stud. 2015, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mañas-Rodríguez, M.Á.; Giménez-Guerrero, G.; Muyor-Rodríguez, J.M.; Martínez-Tur, V.; Moliner-Cantos, C.P. Los tangibles como predictores de la satisfacción del usuario en servicios deportivos. Psicothema 2008, 20, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.D.; Taylor, P.; Shibli, S. Measuring customer service quality of English public sport facilities. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2009, 6, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.; Ferreira, J.J.; São João, R. Creation of value for business from the importance-performance analysis: The case of health clubs. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2019, 23, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ramos, M.; Serrano-Gómez, V.; García-García, O. ¿Existen diferencias en la calidad percibida y satisfacción del usuario que asiste a un centro deportivo de titularidad privada o pública? Un estudio piloto. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2016, 16, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cañamero, S.; García-Unanue, J.; Felipe, J.L.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Gallardo, L. Why do clients enrol and continue at sports centres? Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 9, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Pan, L.Y.; Hsu, C.H.; Lee, D.C. Exploring the Sustainability Correlation of Value Co-Creation and Customer Loyalty—A Case Study of Fitness Clubs. Sustainability 2018, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Codes | Grounded | Families |

|---|---|---|

| Human resources | 129 | Customer service |

| Instructors | 23 | |

| Loyalty | 18 | |

| Reception | 11 | |

| Personal treat | 7 | |

| Familiar treat | 5 | |

| Complaints | 4 | |

| Group classes | 46 | Offered service |

| Service quality | 20 | |

| Technology | 5 | |

| Supplementary services | 2 | |

| Traditional tools | 17 | |

| Business competition | 15 | Marketing |

| Recommendation | 22 | |

| Brand image | 12 | |

| Special offers | 7 | |

| Social networks | 6 | |

| Customer acquisition | 6 | |

| Locker rooms | 38 | Facilities |

| Level of maintenance | 21 | |

| Cleanliness | 19 | |

| Large spaces | 15 | |

| Equipment | 15 | |

| Importance | 13 | |

| Price | 29 | General terms and conditions |

| Location | 22 | |

| Opening days | 21 | |

| Opening hours | 20 | |

| On-site parking | 6 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

León-Quismondo, J.; García-Unanue, J.; Burillo, P. Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125067

León-Quismondo J, García-Unanue J, Burillo P. Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125067

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeón-Quismondo, Jairo, Jorge García-Unanue, and Pablo Burillo. 2020. "Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125067

APA StyleLeón-Quismondo, J., García-Unanue, J., & Burillo, P. (2020). Best Practices for Fitness Center Business Sustainability: A Qualitative Vision. Sustainability, 12(12), 5067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125067