Sustaining Students’ Identities within the Context of Participatory Culture. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating an Interactive Learning Activity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

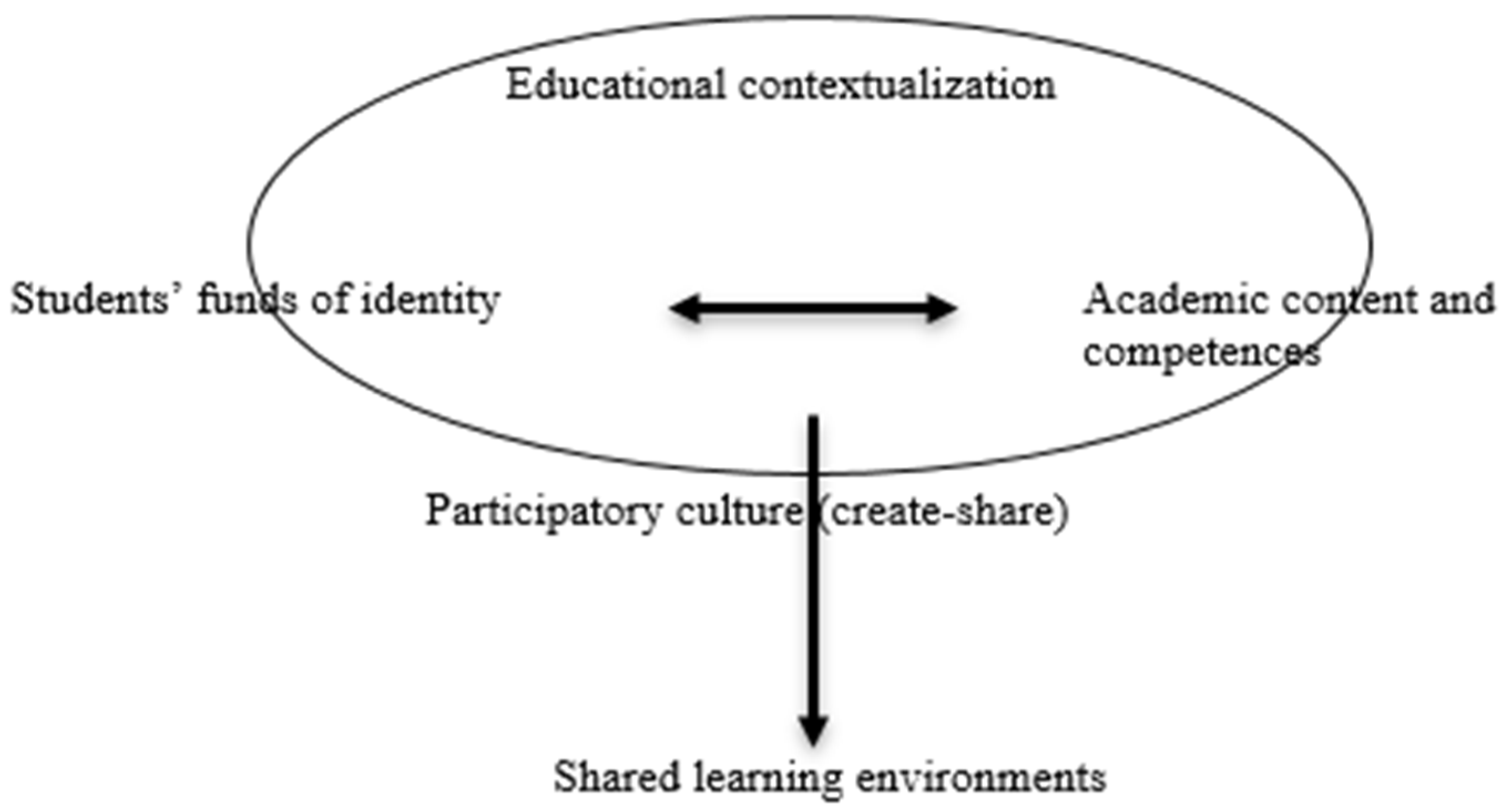

Funds of Knowledge, Funds of Identity and Funds of Identity 2.0

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

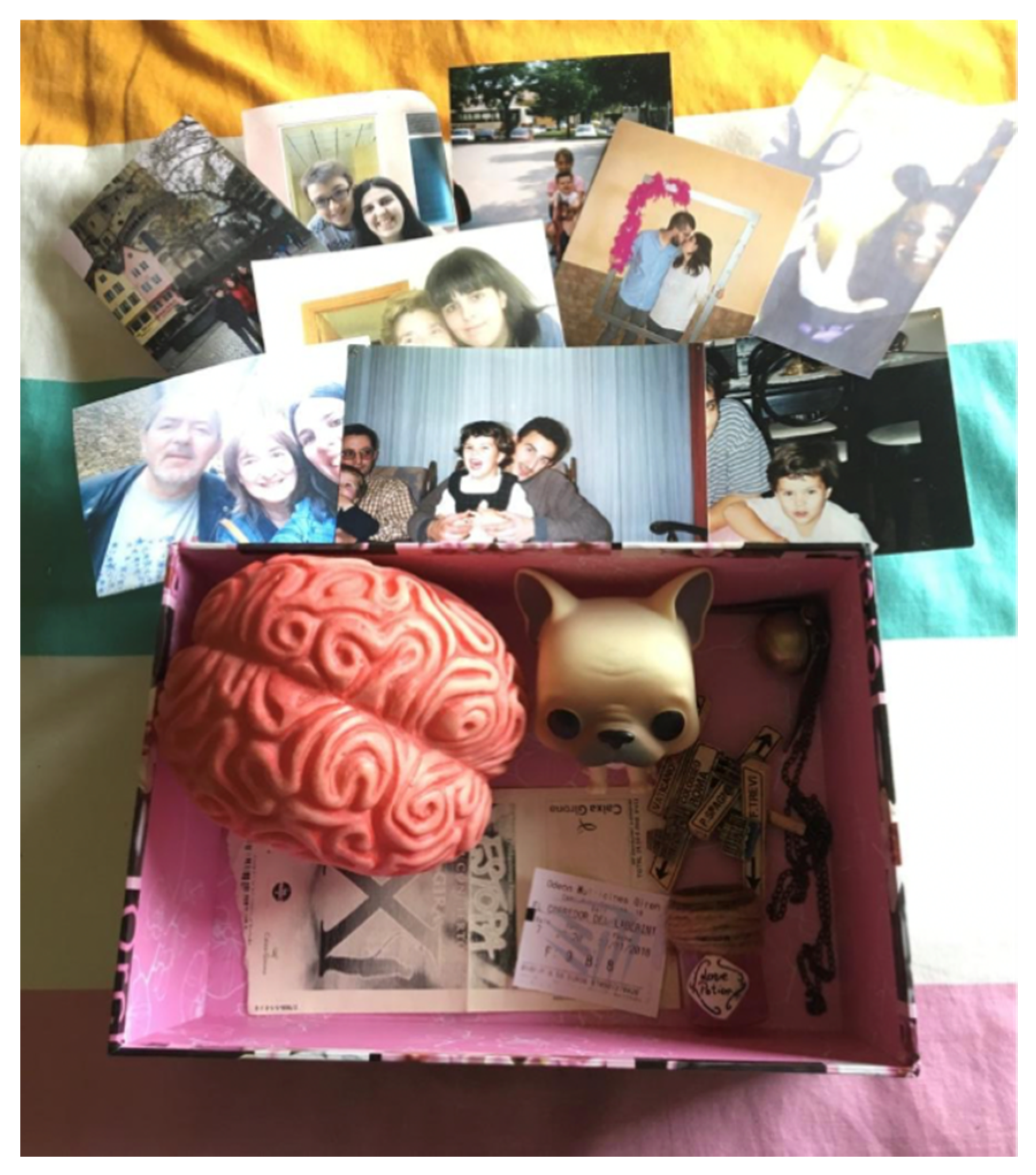

3.1. Phase 1. Identity Artifacts and Funds of Identity

3.2. Phases 2, 3 and 4. Linking of Funds of Identity with the Subject

3.3. Phase 5. Self-Evaluation and Learning Obtained

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barron, B. Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Hum. Dev. 2006, 49, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erstad, O. Digital Learning Lives; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Coll, C.; Penuel, B. Learning across settings and time in the Digital age. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2018, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Designing for deep learning in the context of digital and social media. Comun. Media Educ. Res. J. 2019, 58, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liin, G. Sustainability in lifelong learning: Learners’ perceptions from a Turkish distance language education context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomé, M.; Herrera, L.; Lozano, S. Teachers’ opinions on the use of personal learning environments for intercultural competence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bower, M. Deriving a typology of Web 2.0 learning technologies. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2015, 47, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.H. Technology-enhanced learning: An optimal CPS learning application. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Churchill, D. Educational applications of Web 2.0: Using blogs to support teaching and learning. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 40, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martínez, J.; Serrat-Sellabona, E.; Estebanell-Minguell, M.; Rostan-Sánchez, C.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Sobre el concepto de alfabetización transmedia en el ámbito educativo: Una revisión de la literatura. Comun. Soc. 2018, 33, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-García, R.; López-Martin, C.; Arguedas-Sanz, R. Collaborative learning communities for sustainable employment through visual tools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gee, J.P. Teaching, Learning, Literacy in Our High-Risk, High-Tech World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Serra, J.M.; Vila, I. Informationalism and informalization of learnings in 21st century: A qualitative study on meaningful learning experiences. Soc. Educ. Hist. 2017, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Patiño, J.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Some of the Challenges and Experiences of Formal Education in a Mobile-Centric Society. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2014, 15, 64–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Ito, M.; Boyd, D. Participatory Culture in a Networked Era. A Conversation on Youth, Learning, Commerce and Politics; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Martin, C.; Pfister, R.C.; Rafalow, M.H.; Salen, K.; Wortman, A. Affinity Online: How Connection and Shared Interest Fuel Learning; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Participatory Culture. Interviews; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhardt, A.; Purcell, K.; Smith, A.; Zickuhr, K. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use among Teens and Young Adults; Pew Internet & American Life Project: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- González, N.; Moll, L.; Amanti, C. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1–307. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, L. Vygotsky and Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, L. Elaborating funds of knowledge: Community-oriented practices in international contexts. Lit. Res. 2019, 67, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L. Hacia un Curriculum Cultural. La Vigencia de Vygotski en la Educación; Álvarez, A., Ed.; Infancia y Aprendizaje: Madrid, Spain, 1997; Chapter 3; pp. 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tharp, R.G. Four hundred years of evidence: Culture, Pedagogy, and Native America. J. Am. Ind. Educ. 2006, 45, 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, L. Making school relevant for at-risk students: The Wai’anae High School Hawaiian Studies Program. J. Educ. Stud. Places At-Risk 2003, 8, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, R.R. The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thought and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–287. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, E.; Rosebery, A.; González, N. Classroom Diversity: Connecting Curricula to Students’ Lives; Heinemann: Portsmouth, MH, USA, 2001; pp. 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Serra, J.M.; Llopart, M. The role of the study group in the founds of knowledge approach. Mind Cult. Act. 2018, 25, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, L. Funds of knowledge: An investigation of coherence within the literature. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopart, M.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Funds of knowledge in 21st century societies: Inclusive educational practices for under-represented students: A literatura review. J. Curric. Stud. 2018, 50, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovés, P.; Siqués, C.; Esteban-Guitart, M. The incorporation of funds of knowledge and funds of identity of students and their families into educational practice: A case study from Catalonia, Spain. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 49, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Wyman, L.; O’Connor, B. The past, present, and future of “Funds of knowledge”. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Education; Levinson, B.A., Pollock, M., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 479–494. [Google Scholar]

- Llopart, M.; Serra, J.M.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Teachers’ perceptions of the benefits, limitations, and areas for improvement of the funds of knowledge approach: A qualitative study. Teach. Teach. 2018, 24, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Towards a multimethodological approach to identification of funds of identity, small stories and master narratives. Narrat. Inq. 2012, 22, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M. Funds of Identity. Connecting Meaningful Learning Experiences in and Out of School; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Moll, L.C. Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Cult. Psychol. 2014, 20, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saubich, X.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Bringing funds of family knowledge to school: The living Morocco project. REMIE Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subero, D.; Llopart, M.; Siqués, C.; Esteban-Guitart, M. The mediation of teaching and learning processes through identity artifacts: A Vygotskian perspective. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2018, 44, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopart, M.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Strategies and resources for contextualizing the curriculum based on the funds of knowledge approach: A literature review. Aust. Educ. Res. 2017, 44, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subero, D.; Vujasinovic, E.; Esteban-Guitart, M. Mobilizing funds of identity in and out of school. Camb. J. Educ. 2017, 47, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Moll, L. Lived Experiences, Funds of Identity and Education. Cult. Psychol. 2014, 20, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A. Funds of knowledge 2.0: Towards digital funds of identity. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2017, 13, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Lalueza, J.L.; Zhang-Yu, C.; Llopart, M. Sustaining students’ cultures and identities: A qualitative study based on the funds of knowledge and identity approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteban-Guitart, M.; Gee, J.P. “Inside the head and out in the world.” An approach to deep teaching and learning. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renninger, K.A.; Hidi, S.W. To level the playing field, develop interest. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2020, 7, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Instruction | Period (Length of Time Allocated for the Task) |

|---|---|---|

| 1st phase: What are my funds of identity? | Depict—by means of a graph, map, drawing, collage, photograph, text, or any other resource or medium, what is most significant or most important to you, what best defines you. It may be people, institutions, objects, activities, hobbies, knowledge, ideas, interests, spaces or places that are relevant to you. | 1 week |

| 2nd phase: What content, topic and competence can I relate them to? | Link any of the elements depicted in the first task to a content, topic or competence included in the subject Educational Psychology. These may be topics, authors, competences or contents that are part of the syllabus. To do this, you must familiarize yourself with the contents and competences included in the subject by consulting the guide or overview, as well as the reference manuals, articles or texts that are recommended within the framework of the subject. | 1 month |

| 3rd phase: What work or research am I going to do? | Now it is time to develop the chosen content or competence. That is, to look for information and construct knowledge regarding the understanding of “x” as content or the development of “x” as a competence. To do this, you will have to do research work on the subject using reliable resources and funds: bibliography, interviews with experts, fieldwork, etc. | 1 month |

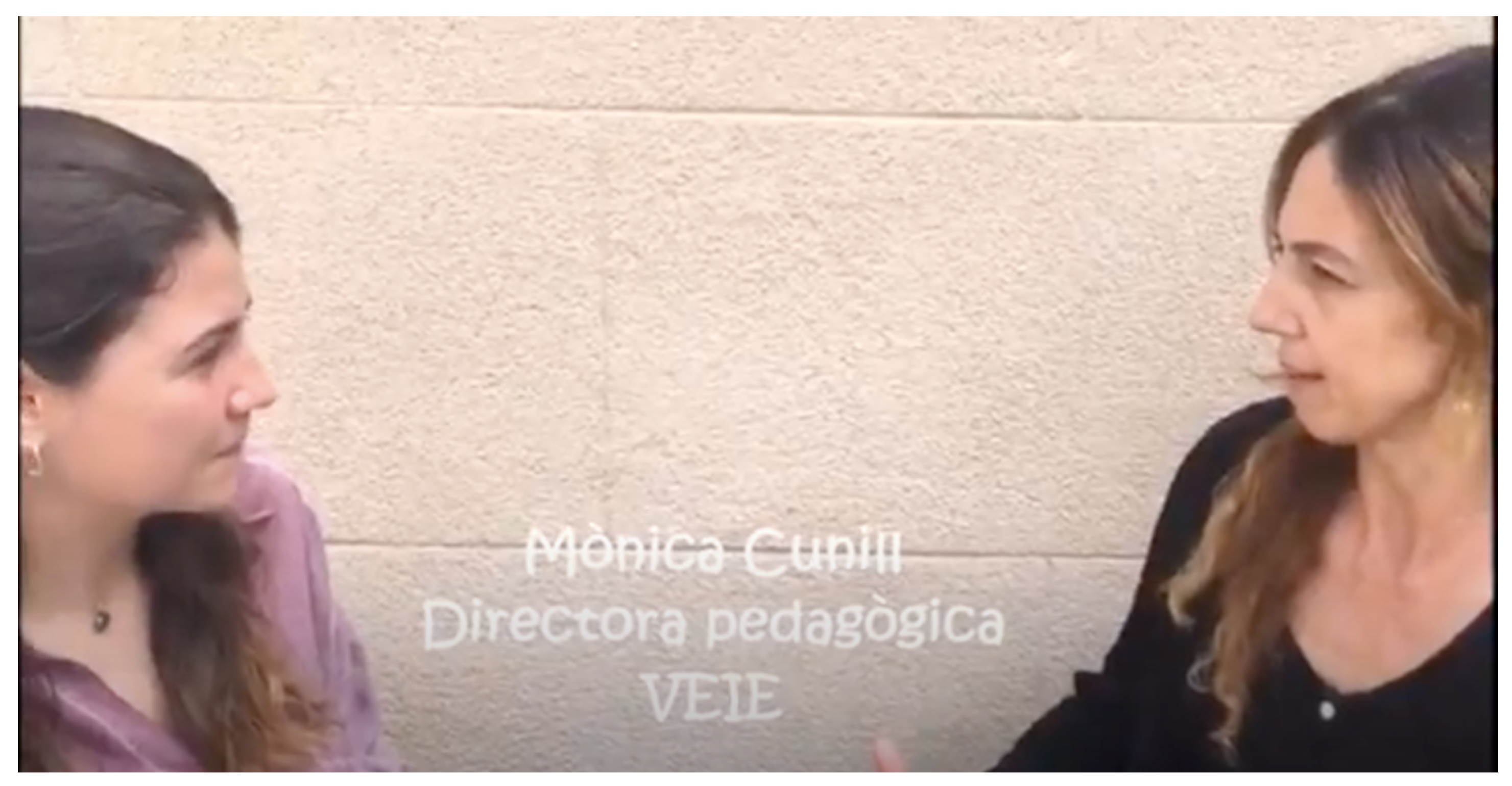

| 4th phase: How am I going to share it and with whom? | Next, you will make a short video (about 2–5 min in length), where you summarize the most significant aspects of the work you have done, and then share it on the YouTube channel “UdG Psicologia-Educació”. This video might contain a PowerPoint presentation, an interview, fieldwork, a mixture of content (texts, photographs), etc., related to a particular author, subject, content, or competence connected to the subject (the author, subject, content or competence selected in stage 2). | 1 month |

| 5th phase: How do I evaluate it? | Finally, describe what you have learned from the project, what you should improve and how, and then grade your task, from 0 to 2, in accordance with the length and breadth of your learning process, with 2 being the maximum level of acquired learning. | 1 week |

| Types of Funds of Identity | Number of Times They Appear in the 60 Identity Artifacts |

|---|---|

| Geographical funds of identity (cities, spaces, countries) | 29 |

| Social funds of identity (family, couple, friends) | 121 |

| Cultural funds of identity (physical and symbolic artifacts) | 33 |

| Identity practices (hobbies, activities such as music or sports) | 53 |

| Institutional funds of identity (reference to institutions such as the Church) | 36 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esteban-Guitart, M.; Monreal-Bosch, P.; Palma, M.; González-Ceballos, I. Sustaining Students’ Identities within the Context of Participatory Culture. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating an Interactive Learning Activity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124870

Esteban-Guitart M, Monreal-Bosch P, Palma M, González-Ceballos I. Sustaining Students’ Identities within the Context of Participatory Culture. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating an Interactive Learning Activity. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124870

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsteban-Guitart, Moisès, Pilar Monreal-Bosch, Montserrat Palma, and Irene González-Ceballos. 2020. "Sustaining Students’ Identities within the Context of Participatory Culture. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating an Interactive Learning Activity" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124870

APA StyleEsteban-Guitart, M., Monreal-Bosch, P., Palma, M., & González-Ceballos, I. (2020). Sustaining Students’ Identities within the Context of Participatory Culture. Designing, Implementing and Evaluating an Interactive Learning Activity. Sustainability, 12(12), 4870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124870