A Multicriteria Approach for Assessing the Impact of ICT on EU Sustainable Regional Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Improve the four inter-related dimensions of ICT (the 4C Framework): Computers, Connectivity, Content, (human) Capacity.

- The successful application ICT for sustainable development depends on the scalability and the sustainability.

- -

- ICT constitutes just a means of achieving sustainable development.

- -

- Active efforts are required to foster global inclusion.

- -

- Sustainable ICT should be economically feasible and create end-user value.

- -

- ICT for sustainable development research and practice should be participatory, collaborative and empowering for the solutions to be globally consistent and relevant.

- Sustainable ICT should become a globally recognized and funded industry.

- -

- Inspire and effectively engage all relevant stakeholders to have a shared vision to implement sustainable ICT.

- -

- Develop metrics to quantify the level of success and effectiveness and consider new academic rigor.

- -

- Focus on the challenges of modernization.

- -

- Plan innovative models for research and development.

- Information and Communication Technology (ICT).

- Research and Innovation (R&I).

- Enhancing the competitiveness of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs).

- Transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Define the preferences: this function deals with the decision-maker’s preference for an alternative xk with respect to another alternative xl regarding a criterion.

- (2)

- Calculate the preference index: this index is used to compare the alternatives in pairs, quantitatively taking into consideration all the defined criteria.

- (3)

- Construct valued outranking graph: outgoing and incoming flows are determined by means of relevant preference indices.

- (4)

- Rank alternatives according to the valued outranking graph: determination of the weights is an important step in most multi-criteria methods [45].

- there is now so much sensitivity of the estimated relation in small changes.

- the results can be easily interpreted and discussed.

- the use of the superiority relation is applied when the alternatives (sustainable regional policies) have to be ranked from the alternative with the highest score to the alternative with the lowest score.

- the assessment and ranking process of complicated cases of sustainable regional policies is suitable for the application of PROMETHEE II methodology in the way that it seems to be closer to reality.

3. Results

4. Discussion

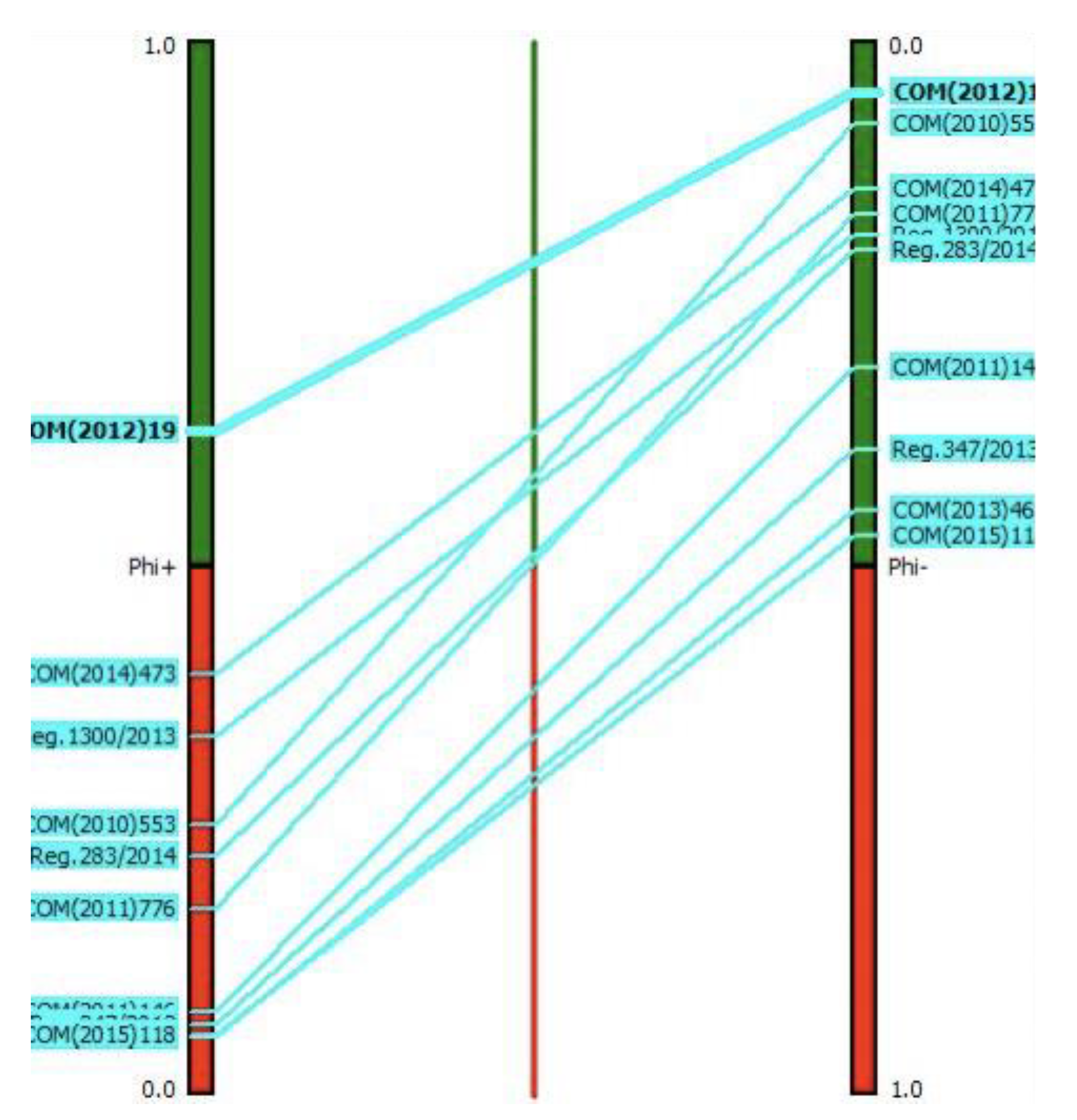

- PROMETHEE II analysis shows that ICT has the strongest impact on COM(2012)19 “Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE)”, while Reg.2015/207 “The models for the progress report, submission of the information on a major project, the joint action plan, the implementation reports for the Investment for growth and jobs goal, the management declaration, the audit strategy, the audit opinion and the annual control report and the methodology for carrying out the cost- benefit analysis” is ranked in the second position.

- The same analysis shows that ICT has the weakest impact on COM(2015)118 “The Agreement on the European Economic Area”.

- Most EU sustainable regional policies adopt ICT solutions, as most of them contribute positively to their total net flows (Phi).

- The large spectrum of the values of the total net flows (Phi) shows a great difference concerning “superiority” between the first and the last EU regional policies, according to the impact of ICT.

- GAIA analysis depicts that COM(2012)19 has the strongest impact of ICT and COM(2015)118 has the weakest impact of ICT.

- MCDA and GAIA analyses provide similar results in terms of scenario ranking.

- “The requirement of the design of new business processes” and “The requirement of collaboration between ICT systems of multiple DGs or institutions/organizations” are found to be the most robust criteria in the PROMETHEE II ranking.

- “The imposition of authentication requirements by the legislation” and “The requirement of new interoperability specifications” are found to be the weakest criteria.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Title | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reg.1083/2006 | General provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund and the Cohesion Fund. |

| 2 | Reg.1081/2006 | European Social Fund. |

| 3 | Reg.1082/2006 | A European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC). |

| 4 | Reg.1290/2005 | Financing of the common agricultural policy. |

| 5 | Reg.2012/2002 | Establishing the European Union Solidarity Fund. |

| 6 | Reg.1301/2013 | The European Regional Development Fund and on specific provisions concerning the Investment for growth and jobs goal. |

| 7 | Reg.1304/2013 | The European Social Fund and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1081/2006. |

| 8 | Reg.1299/2013 | Specific provisions for the support from the European Regional Development Fund to the European territorial cooperation goal. |

| 9 | Reg.1303/2013 | Common provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and laying down general provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. |

| 10 | Reg.1300/2013 | Cohesion Fund and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1084/2006. |

| 11 | Reg.347/2013 | Guidelines for trans-European energy infrastructure. |

| 12 | Reg.283/2014 | Guidelines for trans-European networks in the area of telecommunications infrastructure. |

| 13 | Reg.1828/2006 | Rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 1083/2006 laying down general provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund and the Cohesion Fund and of Regulation (EC) No 1080/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Regional Development Fund. |

| 14 | Reg.1445/2007 | Common rules for the provision of basic information on Purchasing Power Parities and for their calculation and dissemination. |

| 15 | Reg.1059/2003 | Establishment of a common classification of territorial units for statistics (NUTS). |

| 16 | Reg.231/2014 | Establishing an Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA II). |

| 17 | Reg.1085/2006 | Establishing an Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA). |

| 18 | Reg.240/2014 | The European code of conduct on partnership in the framework of the European Structural and Investment Funds. |

| 19 | Reg.2015/207 | The models for the progress report, submission of the information on a major project, the joint action plan, the implementation reports for the Investment for growth and jobs goal, the management declaration, the audit strategy, the audit opinion and the annual control report and the methodology for carrying out the cost-benefit analysis. |

| 20 | COM(2014)473 | Sixth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion: investment for jobs and growth. |

| 21 | COM(2009)295 | Classification of certain goods in the Combined Nomenclature. |

| 22 | COM(2008)371 | Fifth progress report on economic and social cohesion Growing regions, growing Europe. |

| 23 | COM(2007)273 | Fourth progress report on economic and social cohesion Growing regions, growing Europe. |

| 24 | COM (2004)107 | Arsenic, cadmium, mercury, nickel and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in ambient air. |

| 25 | COM(2006)281 | The Growth and Jobs Strategy and the Reform of European cohesion policy Fourth progress report on cohesion. |

| 26 | COM(2005)192 | Third progress report on cohesion: Towards a new partnership for growth, jobs and cohesion. |

| 27 | COM(2007)798 | Member States and Regions delivering the Lisbon strategy for growth and jobs through EU cohesion policy, 2007–2013. |

| 28 | COM(2008)876 | Cohesion Policy: investing in the real economy. |

| 29 | COM(2008)616 | Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength. |

| 30 | COM(2006)30 | Time to move up a gear: The new partnership for growth and jobs. |

| 31 | COM(2003)690 | A European initiative for growth, investing in networks and knowledge for growth and jobs. Final Report to the European Council. |

| 32 | COM(2014)490 | The urban dimension of EU policies–Key features of an EU urban agenda. |

| 33 | COM(2010)553 | Regional Policy contributing to smart growth in Europe 2020. |

| 34 | COM(2006)675 | A contribution by the Swiss Confederation to the European Union military operation in support of the United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) during the election process (Operation EUFOR RD Congo). |

| 35 | COM(2006)385 | Cohesion Policy and cities: the urban contribution to growth and jobs in the regions. |

| 36 | COM (2009)103 | Insurance against civil liability in respect of the use of motor vehicles, and the enforcement of the obligation to insure against such liability. |

| 37 | COM(2015)118 | The Agreement on the European Economic Area. |

| 38 | COM(1999)54 | Amending Council Directive 66/402/EEC on the marketing of cereal seed. |

| 39 | COM(97)172 | Amending the boundaries of the less-favored areas in the Federal Republic of Germany within the meaning of Council Directive 75/268/EEC. |

| 40 | COM(2002)709 | A framework for target-based tripartite contracts and agreements between the Community, the States and regional and local authorities. |

| 41 | COM(2003)585 | Structural indicator. |

| 42 | COM(2003)811 | Dialogue with associations of regional and local authorities. |

| 43 | COM(2011)146 | Reform of the EU State Aid Rules on Services of General Economic Interest. |

| 44 | COM(2012)19 | Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE). |

| 45 | COM(2014)494 | Guidelines on the application of the measures linking effectiveness of the European Structural and Investment Funds to sound economic governance according to Article 23 of Regulation (EU) 1303/2013. |

| 46 | COM(2011)776 | Seventh progress report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. |

| 47 | COM(2013)463 | Eighth progress report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. The regional and urban dimension of the crisis. |

| 48 | Dec.2006/702 | Community strategic guidelines on cohesion. |

| 49 | Dec.1336/97 | A series of guidelines for trans-European telecommunications networks. |

| 50 | Direct.2008/57 | The interoperability of the rail system within the Community (Recast). |

References

- Hilty, L.M.; Seifert, E.K.; Treibert, R. Information Systems for Sustainable Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.; Murray, A.; Mohamed, M. The role of information and communication technology (ICT) in mobilization of sustainable development knowledge: A quantitative evaluation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, L.M. Information Technology and Sustainability: Essays on the Relationship between Information Technology and Sustainable Development; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Andreopoulou, Z.; Samathrakis, V.; Louca, S.; Vlachopoulou, M. E-Innovation for Sustainable Development of Rural Resources during Global Economic Crisis; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z.; Zopounidis, C.; Lemonakis, C. E-commerce in the Context of Protected Areas Development: A Managerial Perspective Under a Multi-Criteria Approach. In Multiple Criteria Decision Making; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tongia, R.; Subrahmanian, E.; Arunachalam, V. Information and Communications Technology for Sustainable Development: Defining a Global Research Agenda; No. Information and Communications Technology for Sustainable Development: Defining a Global Research Agenda; Allied Publishers Pvt. Ltd.: Bangalore, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.; Watanabe, C.; Li, Y. Institutional structure of sustainable development in BRICs: Focusing on ICT utilization. Technol. Soc. 2009, 31, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, Á.; Serrano, A.; Cabrera, M.; Conte, R. The new digital divide: The confluence of broadband penetration, sustainable development, technology adoption and community participation. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2012, 18, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Kalra, M. Information and Communication Technologies: A bridge for social equity and sustainable development in India. Int. Inf. Libr. Rev. 2006, 38, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pade, C.I.; Mallinson, B.; Sewry, D. An exploration of the categories associated with ICT project sustainability in rural areas of developing countries: A case study of the Dwesa project. In Proceedings of the 2006 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on IT Research in Developing Countries; South African Institute for Computer Scientists and Information Technologists: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; pp. 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z. Classification of ICT in EU Environmental Strategies. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2016, 17, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green infrastructure: Smart conservation for the 21st century. Renew. Resour. J. 2002, 20, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z. Exploring the use of smart services in Forestry. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2019, 20, 1434–1439. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmedi, F.; Ahmedi, L.; O’Flynn, B.; Kurti, A.; Tahirsylaj, S.; Bytyçi, E.; Salihu, A. InWaterSense: An Intelligent Wireless Sensor Network for Monitoring Surface Water Quality to a River in Kosovo. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inform. 2018, 9, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M.R.; Rostami, H.; Samadi, S. Enhancing the Binary Watermark-Based Data Hiding Scheme Using an Interpolation-Based Approach for Optical Remote Sensing Images. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inf. Syst. 2018, 9, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreopoulou, Z.S.; Manos, B.; Polman, N.; Viaggi, D. Agricultural and Environmental Informatics, Governance, and Management: Emerging Research Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Andreopoulou, Z.; Koliouska, C.; Galariotis, E.; Zopounidis, C. Renewable energy sources: Using PROMETHEE II for ranking websites to support market opportunities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada-Infante, L.; Lopez-Narbona, A.M.; Nunez-Elvira, A.; Orozco-Messan, J. Assessing the Efficiency of Sustainable Cities Using an Empirical Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Sustainable development: A new (ish) idea for a new century? Political Stud. 2000, 48, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, A.; Wagner, P. EU regional policy and the stimulation of innovation: The role of the European Regional Development Fund in the objective 1 region Burgenland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohse, D.; Fornahl, D.; Vehrke, J. Fostering place-based innovation and internationalization–the new turn in German technology policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1137–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z. The Typology for ICT adoption of EU environmental policies. Wseas Trans. Comput. 2019, 18, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z.; Misso, R.; Borelli, I.P. Regional sustainability: National Forest Parks in Greece. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inf. Syst. 2017, 8, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Governing the void between stakeholder management and sustainability. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 38, 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Andreopoulou, Z.; Koliouska, C. Benchmarking Internet Promotion of Renewable Energy Enterprises: Is Sustainability Present? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The EU’s Main Investment Policy. 2015. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- European Union. Regional Policy. 2018. Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/regional-policy_en (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- MLIT. An Overview of Spatial Policy in Asian and European Countries. 2016. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Michie, R.; Fitzgerald, R. The evolution of the structural funds. In The Coherence of EU Regional Policy: Contrasting Perspectives on the Structural Funds; Bachtler, J., Turok, I., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Interreg Europe. Perception and Awareness of EU Regional Policy on the Rise. 2017. Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart specialisation, entrepreneurship and SMEs: Issues and challenges for a results- oriented EU regional policy. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.G. An evaluation of EU regional policy. Do structural actions crowd out public spending? Public Choice 2012, 151, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Fuest, C. EU regional policy and tax competition. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, M. EU regional policy and the candidate states: Poland and the Czech Republic. J. Eur. Integr. 2002, 24, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funck, B.; Pizzati, L. European Integration, Regional Policy and Growth; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M. Evaluating EU regional policy: How might we understand the causal connections between interventions and outcomes more effectively? Policy Stud. 2007, 28, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachtler, J.; Mendez, C. EU Cohesion Policy and European Integration: The Dynamics of EU Budget and Regional Policy Reform; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Method for Assessing ICT Implications of EU Legislation. 2010. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/idabc/servlets/Doc792e.pdf?id=32704 (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z.; Golumbeanu, M. The Contribution of ICT in EU Development Policy: A Multicriteria Approach. In Advances in Operational Research in the Balkans; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal, B.; De Smet, Y. Visual PROMETHEE: Developments of the PROMETHEE & GAIA multicriteria decision aid methods. In Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management; IEEM: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 1646–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, J.P.; Vincke, P.; Mareschal, B. How to select and how to rank projects: The PROMETHEE method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 24, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Y. Prioritized multi-criteria decision making based on the idea of PROMETHEE. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 17, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Τsolaki-Fiaka, S.; Bathrellos, G.D.; Skilodimou, H.D. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis for an Abandoned Quarry in the Evros Region (NE Greece). Land 2018, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. PROMETHEE methods. In Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- Andreopoulou, Z.; Koliouska, C.; Zopounidis, C. Multicriteria and Clustering: Classification Techniques in Agrifood and Environment; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Macharis, C.; Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. The GDSS promethee procedure. J. Decis. Syst. 1998, 7, 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Mareschal, B. Visual PROMETHEE 1.4 Manual; Visual PROMETHEE: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zopounidis, C. Analysis of Financing Decisions with Multiple Criteria; Anikoula Publications: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunications Union. ICTs for a Sustainable World. 2018. Available online: https://www.itu.int (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Macharis, C.; Springael, J.; De Brucker, K.; Verbeke, A. PROMETHEE and AHP: The design of operational synergies in multicriteria analysis: Strengthening PROMETHEE with ideas of AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 153, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Dependence on the ICT solutions | X1 | Does the legislation require the design of information rich processes? |

| X2 | Does the legislation require the design of new business processes? | |

| X3 | Are large amounts of data gathering required in these processes? | |

| X4 | Is collaboration between ICT systems of multiple DGs or institutions/organizations required? | |

| X5 | Is the legislation concerning ICT systems or is ICT a supporting function of the legislation? | |

| Complexity of the ICT solutions | X6 | Does the legislation require new ICT solutions or can existing applications fulfill the requirements? |

| X7 | Are there any legacy systems which might hamper the implementation? | |

| X8 | Does the legislation impose authentication requirements? | |

| X9 | Is a large amount of data exchange between member states and/or the Commission required? | |

| X10 | What is the required lead-time of the implementation (urgency)? | |

| X11 | Are new interoperability specifications required? | |

| X12 | Does the initiative impose high security requirements on the ICT solution? |

| Regional Policy | Phi+ | Phi- | Phi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COM(2012)19 | 0.631 | 0.0469 | 0.5841 |

| 2 | Reg.2015/207 | 0.3992 | 0.1391 | 0.26 |

| 3 | COM(2014)473 | 0.3992 | 0.1391 | 0.26 |

| 4 | Reg.1301/2013 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 5 | Reg.1304/2013 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 6 | Reg.1299/2013 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 7 | Reg.1303/2013 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 8 | Reg.231/2014 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 9 | COM(2010)553 | 0.2556 | 0.0778 | 0.1778 |

| 10 | Reg.1300/2013 | 0.3401 | 0.184 | 0.1561 |

| 11 | Reg.283/2014 | 0.2256 | 0.1983 | 0.0273 |

| 12 | COM(2011)776 | 0.1752 | 0.1633 | 0.0119 |

| 13 | COM(2014)490 | 0.077 | 0.3094 | −0.2324 |

| 14 | COM(2011)146 | 0.077 | 0.3094 | −0.2324 |

| 15 | Reg.347/2013 | 0.0667 | 0.3865 | −0.3198 |

| 16 | Reg.240/2014 | 0.0547 | 0.4445 | −0.3899 |

| 17 | COM(2014)494 | 0.0547 | 0.4445 | −0.3899 |

| 18 | COM(2013)463 | 0.0547 | 0.4445 | −0.3899 |

| 19 | COM(2015)118 | 0.0564 | 0.4687 | −0.4123 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koliouska, C.; Andreopoulou, Z. A Multicriteria Approach for Assessing the Impact of ICT on EU Sustainable Regional Policy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124869

Koliouska C, Andreopoulou Z. A Multicriteria Approach for Assessing the Impact of ICT on EU Sustainable Regional Policy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124869

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoliouska, Christiana, and Zacharoula Andreopoulou. 2020. "A Multicriteria Approach for Assessing the Impact of ICT on EU Sustainable Regional Policy" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124869

APA StyleKoliouska, C., & Andreopoulou, Z. (2020). A Multicriteria Approach for Assessing the Impact of ICT on EU Sustainable Regional Policy. Sustainability, 12(12), 4869. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124869