Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Value Chains in Mali: Issues, Needs, and Opportunities for Their Sustainable Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

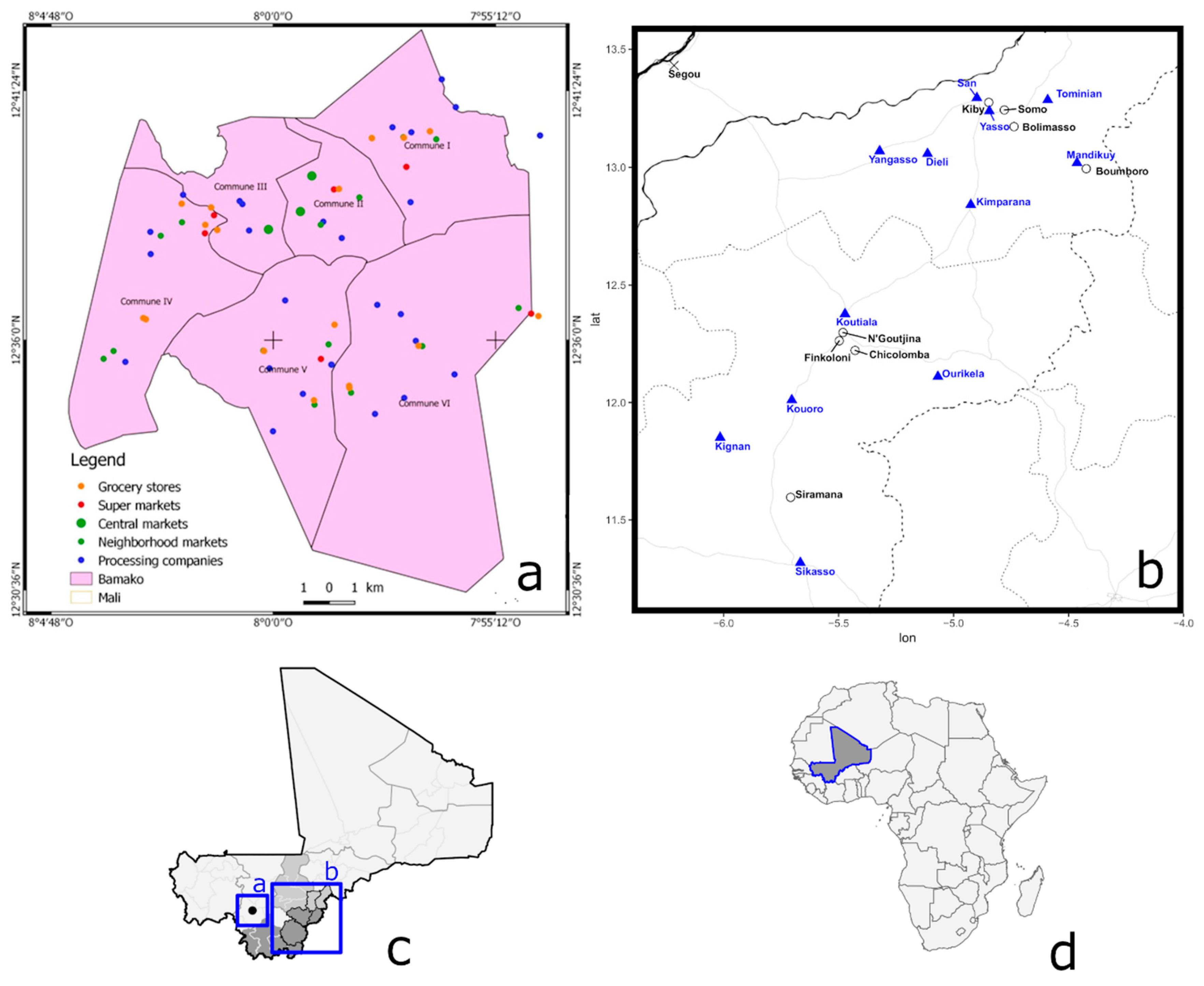

- Bamako: Situated in the central south of Mali, Bamako is the capital city, home to approximately 10% of the national population (pop. 2,009,109, Population Census 2009). Bamako is the biggest urban center in Mali and, therefore, constituted an important ‘barometer’ to assess the commercial integration of marginal crops.

- Cercle de San and Tominian in the Ségou region, with San as a main urban center (pop. 68,078, Population Census 2009). Agriculture is the predominant sector in the Ségou region. The study area was within the north Sudano-Sahelian production zone (sensu [39]), where cropping systems are based on pearl millet and sorghum complemented by peanut. Among the different regions of Mali, the greatest production of fonio and Bambara groundnut has been recorded in Ségou, which accounted for 52% and 50% of national production of these crops, respectively, in 2015 [38]. The area around San and Tominian was targeted by the study because it is known as a major production area for fonio [40].

- Cercle de Koutiala and Cercle de Sikasso in the Sikasso region, with Koutiala and Sikasso as the main urban centers (respective pop. 137,919 and 225,753, Population Census 2009). Among the regions of Mali, Sikasso is an important contributor to the national agricultural output, and it benefits from above-average soil fertility. The region is the biggest cereal producer of the country, often considered Mali’s ‘granary’. In 2015, it produced 29% of the national cereal production and 67% of maize production [38]. The cropping systems in these areas are dominated by rainfed cotton and maize grown with mineral fertilizer and organic manure, while tubers, vegetables, and fruits are produced in lowland areas [39,41]. The Sikasso region accounted for 8% of fonio and 7% of Bambara groundnut production in Mali in 2015 [38]. However, in the focal areas of this study, traditional grain crops have been largely displaced with the expansion of cotton and maize production [42,43,44].

2.2. Rapid Market Assessment

2.2.1. Trader Surveys

2.2.2. Producer Surveys

2.2.3. Consumer Surveys

2.2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Trader Surveys

3.1.1. Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Products Traded

3.1.2. Trader Characteristics

3.1.3. Trends and Features of Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Trading

3.2. Producer Surveys

3.2.1. Production Overview

3.2.2. Producers’ Marketing

3.3. Consumer Surveys

3.3.1. Rural Consumer Perceptions

3.3.2. Urban Consumer Perceptions

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Bottlenecks

4.2. Policy Recommendations

4.2.1. Gender Dynamics in Processing and Trading

4.2.2. Visibility and Knowledge of the Crops

4.2.3. Access to Inputs and Machinery

4.2.4. More Resilient Cropping Patterns

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Traore, B.; Corbeels, M.; Van Wijk, M.T.; Rufino, M.C.; Giller, K.E. Effects of climate variability and climate change on crop production in southern Mali. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 49, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Roudier, P.; Quirion, P.; Alhassane, A.; Muller, B.; Dingkuhn, M.; Ciais, P.; Guimberteau, M.; Traore, S.; Baron, C. Assessing climate change impacts on sorghum and millet yields in the Sudanian and Sahelian savannas of West Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetani, M.; Janicot, S.; Vrac, M.; Famien, A.M.; Sultan, B. Robust assessment of the time of emergence of precipitation change in West Africa. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrieu, N.; Sogoba, B.; Zougmore, R.; Howland, F.; Samake, O.; Bonilla-Findji, O.; Lizarazo, M.; Nowak, A.; Dembele, C.; Corner-Dolloff, C. Prioritizing investments for climate-smart agriculture: Lessons learned from Mali. Agric. Syst. 2017, 154, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.A.; McCarl, B.A.; Angerer, J.; Dyke, P.T.; Stuth, J.W. The economic and food security implications of climate change in Mali. Clim. Chang. 2005, 68, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.M.; Lopez-Carr, D.; Funk, C.; Husak, G.J.; Chafe, Z.A. Climate change and human health: Spatial modeling of water availability, malnutrition, and livelihoods in Mali, Africa. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; O’Reilly, P.; Walker, S.; Mwale, S. Opportunities for underutilised crops in Southern Africa’s post-2015 development agenda. Sustainability 2016, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Gaetani, M. Agriculture in West Africa in the twenty-first century: Climate change and impacts scenarios, and potential for adaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, A.W. Potential of underutilized traditional vegetables and legume crops to contribute to food and nutritional security, income and more sustainable production systems. Sustainability 2014, 6, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Hlahla, S.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S.; Nhamo, L.; Modi, A.T. Prospects of orphan crops in climate change. Planta 2019, 250, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handschuch, C.; Wollni, M. Traditional food crop marketing in sub-Saharan Africa: Does gender matter? J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.V.; Campanaro, A.; Coccetti, P.; De Giuseppe, R.; Galimberti, A.; Labra, M.; Cena, H. Potential role of neglected and underutilized plant species in improving women’s empowerment and nutrition in areas of sub-Saharan Africa. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietmeyer, N.; Borlaugh, N.; Axtell, J.; Burton, G.; Harlan, J.; Rachie, K. Fonio (Acha). In Lost Crops of Africa; Board on Science and Technology for International Development, National Research Council, National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sidibe, A. Le fonio au Mali. In Proceedings of the Actes du Premier Atelier Sur la Diversité Génétique du Fonio (Digitaria Exilis Stapf.) en Afrique de L’Ouest, Conakry, Guinée, 4–6 August 1998; Vodouhe, S.R., Zannou, A., Achigan-Dako, G.E., Eds.; IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Konkobo-Yaméogo, C.; Chaloub, Y.; Bricas, N.; Karimou, R.; Ndiaye, J.L. La consommation urbaine d’une céréale traditionnelle en Afrique de l’Ouest: Le fonio. Cah. Agric. 2004, 13, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. Teff & Fonio—Africa’s sustainable cereals. Biodiversity 2015, 16, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Temple, V.J.; Bassa, J.D. Proximate chemical composition of Acha (Digitaria exilis) grain. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1991, 56, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barikmo, I.; Ouattara, F.; Oshaug, A. Food Composition Table for Mali; Research series No. 9; Arkhesus University College: Lillestrøm, Norway, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hillocks, R.J.; Bennett, C.; Mponda, O.M. Bambara nut: A review of utilisation, market potential and crop improvement. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2012, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mkandawire, C.H. Review of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) production in Sub-Sahara Africa. Agric. J. 2007, 2, 464–470. [Google Scholar]

- Adebowale, Y.A.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Henle, T. Protein isolates from Bambara groundnut (Voandzeia subterranean L.): Chemical characterization and functional properties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 758–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, R.A.; Barkla, B.J.; Mayes, S.; King, G.J. The potential of the underutilized pulse Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) for nutritional food security. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 77, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam-Ali, S.N.; Sesay, A.; Karikari, S.K.; Massawe, F.J.; Aguilar-Manjarrez, J.; Bannayan, M.; Hampson, K.J. Assessing the potential of an underutilized crop—A case study using Bambara groundnut. Exp. Agric. 2001, 37, 433–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, S.; Ho, W.K.; Chai, H.H.; Gao, X.; Kundy, A.C.; Mateva, K.I.; Zahrulakmal, M.; Hahiree, M.K.I.M.; Kendabie, P.; Licea, L.C.; et al. Bambara groundnut: An exemplar underutilised legume for resilience under climate change. Planta 2019, 250, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodouhe, S.R.; Zannou, A.; Achigan Dako, E. (Eds.) Proceedings of the Actes du Premier Atelier sur la Diversité Génétique du Fonio (Digitaria Exilis Stapf.) en Afrique de L’Ouest, Conakry, Guinée, 4–6 August 1998; IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, J.F. Fonio: A small grain with potential. LEISA 2004, 20, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fogny-Fanou, N.; Koreissi, Y.; Dossa, R.A.; Brouwer, I.D. Consumption of, and beliefs about fonio (Digitaria exilis) in urban area in Mali. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2009, 9, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, C.H.; Borus, D.J. Cereals and Pulses of Tropical Africa. Conclusions and Recommendations Based on PROTA 1: ‘Cereals and Pulses’; PROTA Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Adoukonou-Sagbadja, H.; Dansi, A.; Vodouhè, R.; Akpagana, K. Indigenous knowledge and traditional conservation of fonio millet (Digitaria exilis, Digitaria iburua) in Togo. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 2379–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, P. The Market Potential of Bambara Groundnut. FRI/NRI Project Report; Natural Resources Institute (NRI): Chatham, UK, 2001; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Adzawla, W.; Donkoh, S.A.; Nyarko, G.; O’Reilly, P.; Mayes, S. Use patterns and perceptions about the attributes of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) in Northern Ghana. GJSTD 2016, 4, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, L.; Nyamanda, M.; Mbachi Mwangwela, A.; Bennett, B. Beliefs, taboos and minor crop value chains: The case of Bambara groundnut in Malawi. Food Cult. Soc. 2015, 18, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchie, J.N.; Dapaah, H.K.; Dankyi, A.A.; Plahar, W.A.; Quartey, F.; Haleegoah, J.; Agyei, J.N.; Addo, J.K. Practices and constraints in Bambara groundnuts production, marketing and consumption in the Brong Ahafo and Upper-East Regions of Ghana. J. Agron. 2010, 9, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mubaiwa, J.; Fogliano, V.; Chidewe, C.; Bakker, E.J.; Linnemann, A.R. Utilization of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) for sustainable food and nutrition security in semi-arid regions of Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dury, S.; Meuriot, V. Do urban African dwellers pay a premium for food quality and, if so, how much? An investigation of the Malian fonio grain market. RAEStud 2010, 91, 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Mali Country Fact Sheet on Food and Agriculture Policy Trends; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- République du Mali. Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural; Ministère de l’Agriculture: Bamako, Mali, 2016; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Soumaré, M.; Bazile, D.; Vaksmann, M.; Kouressy, M.; Diallo, K.; Diakité, C.H. Diversité agroécosystémique et devenir des céréales traditionnelles au sud du Mali. Cah. Agric. 2008, 17, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.; Béavogui, F.; Dramé, D.; Diallo, T.A. Fonio, an African Cereal; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2016; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Dufumier, M. Etude des Systèmes Agraires et Yypologie des Systèmes de Production Agricole Dans la Région Cotonnière du Mali; Programme d’Amélioration des Systèmes d’Exploitation en Zone Cotonnière: Bamako, Mali, 2005; pp. 1–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.W.; West, C.T. Unraveling the Sikasso paradox: Agricultural change and malnutrition in Sikasso, Mali. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2017, 56, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djouara, H.; Bélières, J.-F.; Kébé, D. Les exploitations agricoles familiales de la zone cotonnière du Mali face à la baisse des prix du coton-graine. Cah. Agric. 2006, 15, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kouressy, M.; Bazile, D.; Michel, V.; Mamy, S.; Doucouré, C.O.T.; Sidibé, A. La dynamique des agroécosystèmes: Un facteur explicatif de l’érosion variétale du sorgho: Le cas de la zone Mali-sud. In Proceedings of the Organisation Spatiale et Gestion des Ressources et des Territoires Ruraux: Actes du Colloque International, Montpellier, France, 25–27 February 2003; Dugué, P., Jouve, P., Eds.; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Theriault, V.; Vroegindewey, R.; Assima, A.; Keita, N. Retailing of processed dairy and grain products in Mali: Evidence from a city retail outlet inventory. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, N.; Padulosi, S.; Meldrum, G. Value Chain Analysis of Chaya (Mayan Spinach) in Guatemala. Econ. Bot. 2019, 72, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldermann, S.; Blagojević, L.; Frede, K.; Klopsch, R.; Neugart, S.; Neumann, A.; Ngwene, B.; Norkeweit, J.; Schröter, D.; Schröter, A.; et al. Are Neglected Plants the Food for the Future? Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2016, 35, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruère, G.P.; Giuliani, A.; Smale, M. Marketing underutilized plant species for the benefit of the poor: A conceptual framework. In Agrobiodiversity Conservation and Economic Development; Kontoleon, A., Pasqual, U., Smale, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Vall, E.; Andrieu, N.; Beavogui, F.; Sogodogo, D. Les cultures de soudure comme strategie de lutte contre l’insecurite alimentaire saisonniere en Afrique de l’Ouest: Le cas du fonio (Digitaria exilis Stapf). Cah. Agric. 2011, 20, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Maseko, I.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Tesfay, S.; Araya, H.; Fezzehazion, M.; Plooy, C. African leafy vegetables: A review of status, production and utilization in South Africa. Sustainability 2017, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodouhe, R.S.; Dako, G.A.; Dansi, A.; Adoukonou-Sagbadja, H. Fonio: A treasure for West Africa. In Plant Genetic Resources and Food Security in West and Central Africa. Regional Conference, 26-30 April 2004; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2007; Volume 472, p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Nwadi, O.M.; Uchegbu, N.; Oyeyinka, S.A. Enrichment of food blends with bambara groundnut flour: Past, present, and future trends. Legume Sci. 2020, 2, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimu, B.; Aliyu, L. Country Reports: Northern Nigeria. In Proceedings of the workshop on conservation and improvement of Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.), Harare, Zimbabwe, 14–16 November 1995; Heller, J., Begemann, F., Mushonga, J., Eds.; Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research: Rome, Italy, 1997; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Aviara, N.A.; Lawal, A.A.; Atiku, A.A.; Haque, M.A. Bambara groundnut processing, storage and utilization in north east-ern Nigeria. Cont. J. Eng. Sci. 2013, 8, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sidibé, A.; Meldrum, G.; Coulibaly, H.; Padulosi, S.; Traore, I.; Diawara, G.; Sangaré, A.R.; Mbosso, C. Revitalizing cultivation and strengthening the seed systems of fonio and Bambara groundnut in Mali through a community biodiversity management approach. Plant Genet. Resour. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruère, G.; Giuliani, A.; Smale, M. Marketing Underutilized Plant Species for the Benefit of the Poor: A Conceptual Framework; EPT discussion Paper 154; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Padulosi, S.; Meldrum, G.; Gullotta, G. (Eds.) Agricultural biodiversity to manage the risks and empower the poor. In Proceedings of the International Conference, Rome, Italy, 27–29 April 2015; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Borelli, T.; Hunter, D.; Padulosi, S.; Amaya, N.; Meldrum, G.; Beltrame, D.M.D.O.; Samarasinghe, G.; Wasike, V.W.; Güner, B.; Tan, A.; et al. Local Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Contribution of Orphan Crops and Wild Edible Species. Agronomy 2020, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polar, V.; Rojas, W.; Jäger, M.; Padulosi, S. Taller de Análisis Multiactoral para la Promoción del Uso Sostenible del Amaranto: Memorias del taller realizado en Sucre, Bolivia, 19-20 de noviembre de 2009; Fundación PROINPA, La Paz, Bolivia and Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, P.C.; Idsardi, E.F. Consumption of indigenous and traditional food crops: Perceptions and realities from South Africa. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanga, B.C.; Kanyama-Phiri, G.Y.; Waddington, S.R.; Almekinders, C.J.; Giller, K.E. The evaluation and adoption of annual legumes by smallholder maize farmers for soil fertility maintenance and food diversity in central Malawi. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, T.A. Le fonio: Un regain d’intérêt en Afrique de l’ouest. In Plant Genetic Resources and Food Security in West and Central Africa. Regional Conference, 26–30 April 2004; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2007; Volume 472, p. 213. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Topics Explored |

|---|---|

| Trader level |

|

| Producer level |

|

| Consumer level |

|

| Crop/Product | Description | Level of Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Fonio | ||

| Paddy | Threshed and winnowed fonio as the first step of fonio processing | Basic |

| Whitened | Hulled fonio that receives extra processing to remove the bran (pericarp and germ). | Basic |

| Washed and dried | Whitened fonio that has received additional washing and is subsequently dried | Intermediary |

| Precooked | Steamed, washed, and dried fonio, subsequently dried and packaged | |

| Djouka | Precooked fonio mixed with steamed and crushed groundnuts and potash, subsequently dried and packaged | |

| Bambara groundnut | ||

| Grains | Dried Bambara groundnut grains (seeds) | Basic |

| Roasted | Roasted Bambara groundnut nuts following harvest season | Basic |

| Boiled | Fresh nuts boiled after harvest | Basic |

| Year | Crop | Retailers | Semi-Wholesalers | Wholesalers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Fonio | 49 (53%) | 25 (72%) | 9 (44%) |

| Bambara groundnut | 41 (85%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2018 | Fonio | 208 (78%) | 37 (5%) | 9 (33%) |

| Value Chain Actor | Fonio | Bambara Groundnut |

|---|---|---|

| Traders and processors |

|

|

| Producers |

|

|

| Consumers |

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mbosso, C.; Boulay, B.; Padulosi, S.; Meldrum, G.; Mohamadou, Y.; Berthe Niang, A.; Coulibaly, H.; Koreissi, Y.; Sidibé, A. Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Value Chains in Mali: Issues, Needs, and Opportunities for Their Sustainable Promotion. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114766

Mbosso C, Boulay B, Padulosi S, Meldrum G, Mohamadou Y, Berthe Niang A, Coulibaly H, Koreissi Y, Sidibé A. Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Value Chains in Mali: Issues, Needs, and Opportunities for Their Sustainable Promotion. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114766

Chicago/Turabian StyleMbosso, Charlie, Basile Boulay, Stefano Padulosi, Gennifer Meldrum, Youssoufa Mohamadou, Aminata Berthe Niang, Harouna Coulibaly, Yara Koreissi, and Amadou Sidibé. 2020. "Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Value Chains in Mali: Issues, Needs, and Opportunities for Their Sustainable Promotion" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114766

APA StyleMbosso, C., Boulay, B., Padulosi, S., Meldrum, G., Mohamadou, Y., Berthe Niang, A., Coulibaly, H., Koreissi, Y., & Sidibé, A. (2020). Fonio and Bambara Groundnut Value Chains in Mali: Issues, Needs, and Opportunities for Their Sustainable Promotion. Sustainability, 12(11), 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114766