Qualitative Impact Analysis of International Tourists and Residents’ Perceptions of Málaga-Costa Del Sol Airport

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of Art

- RQ1

- What are the kind of impacts perceived by residents?

- RQ2

- What are the kind of impacts perceived by tourists?

- RQ3

- Are there significant differences between the two groups?

- RQ4

- Is there a relationship between the kind of impact and other variables such as age, gender, or occupation?

- RQ5

- What aspects or improvements need to be developed to help sustain tourism development?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Contextual Background

3.2. Sampling, Data Collection, and Analysis

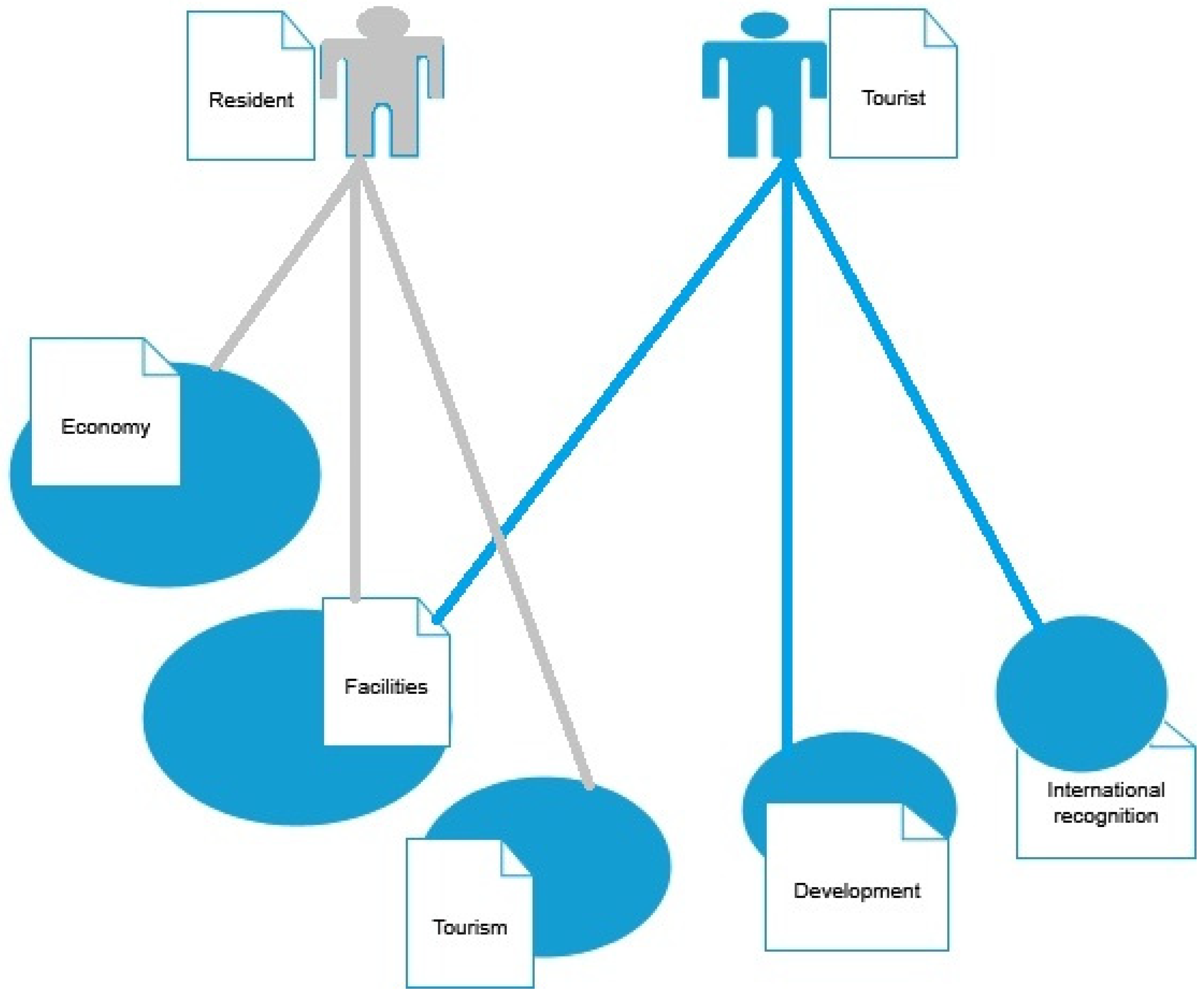

4. Findings

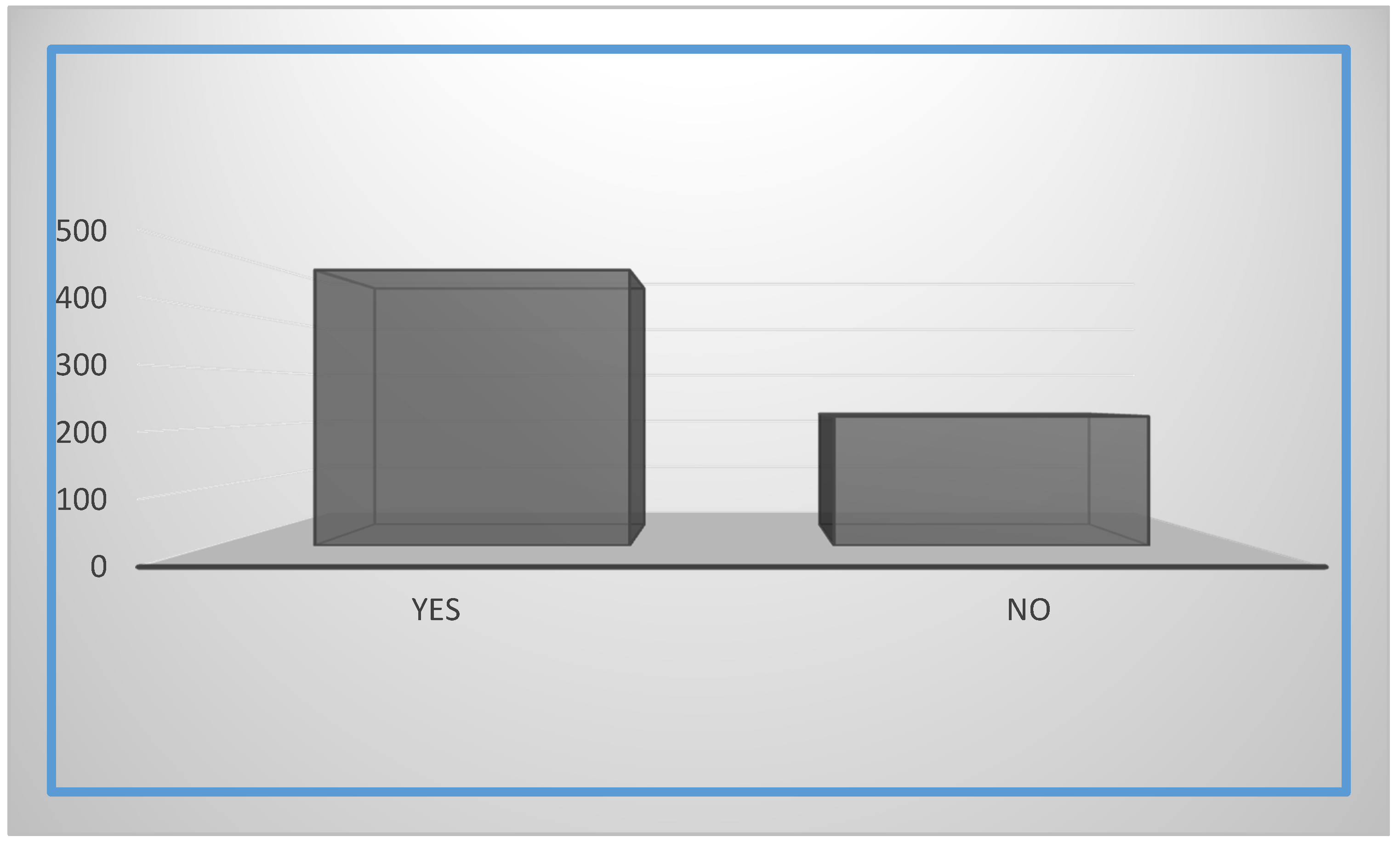

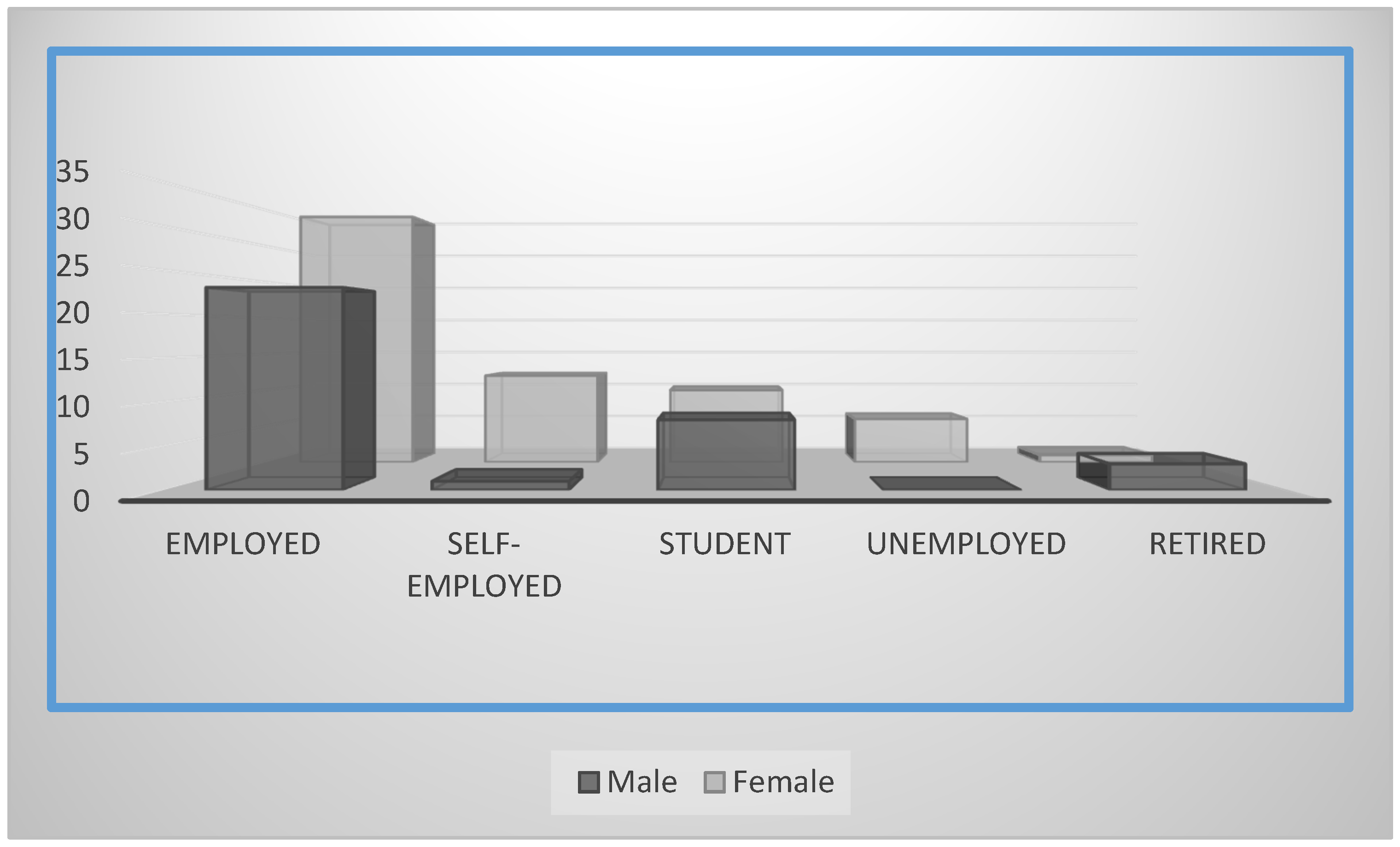

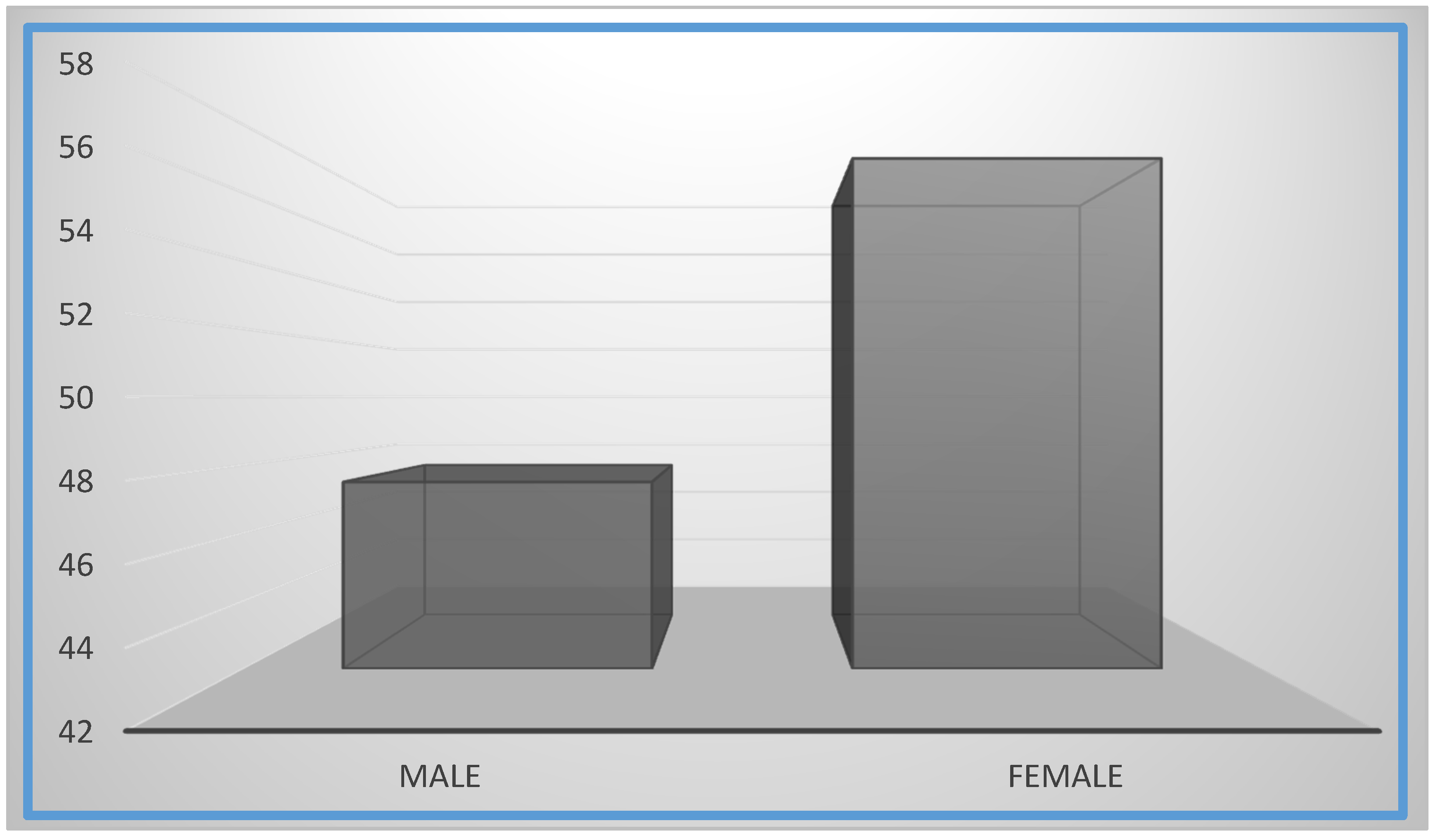

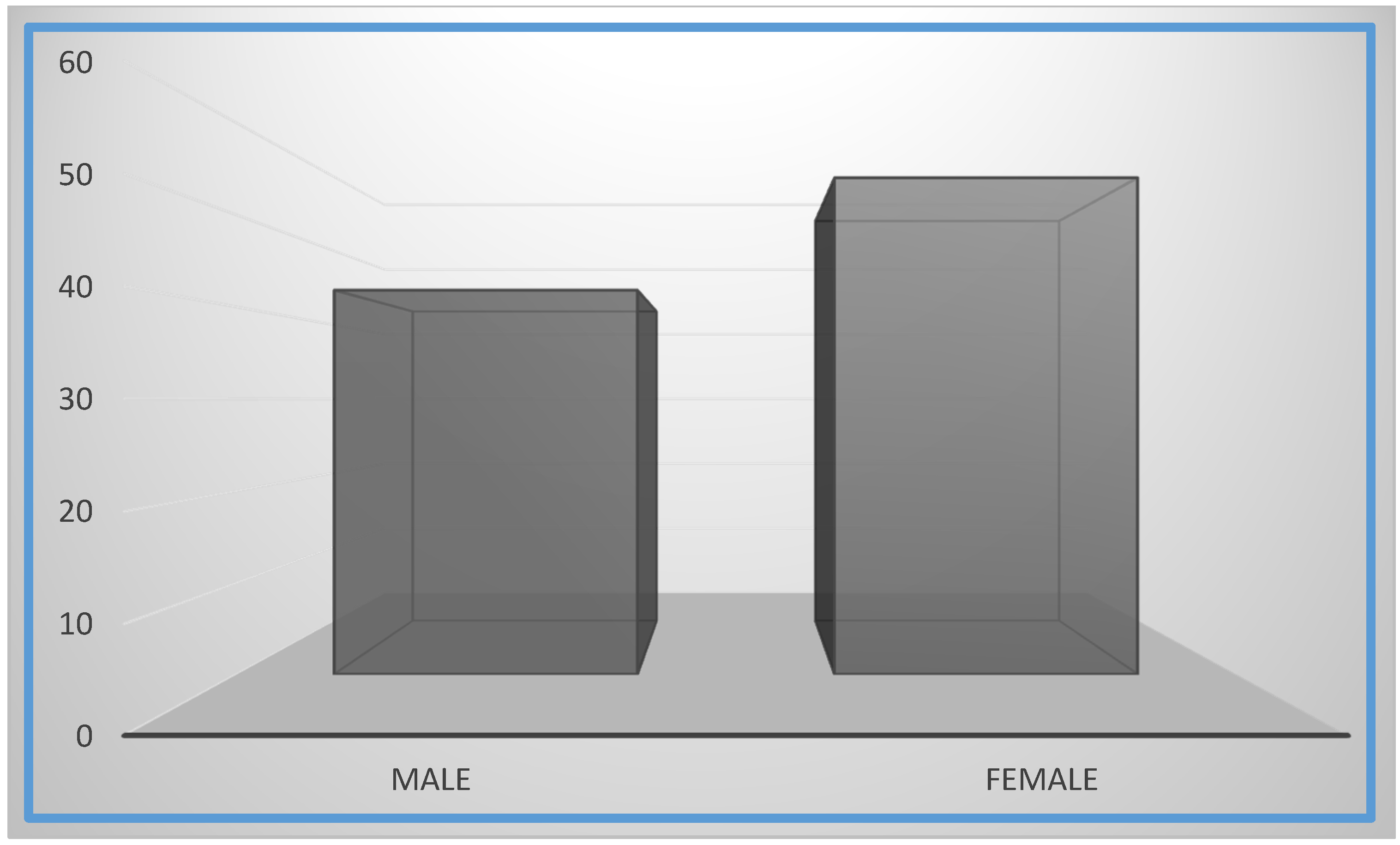

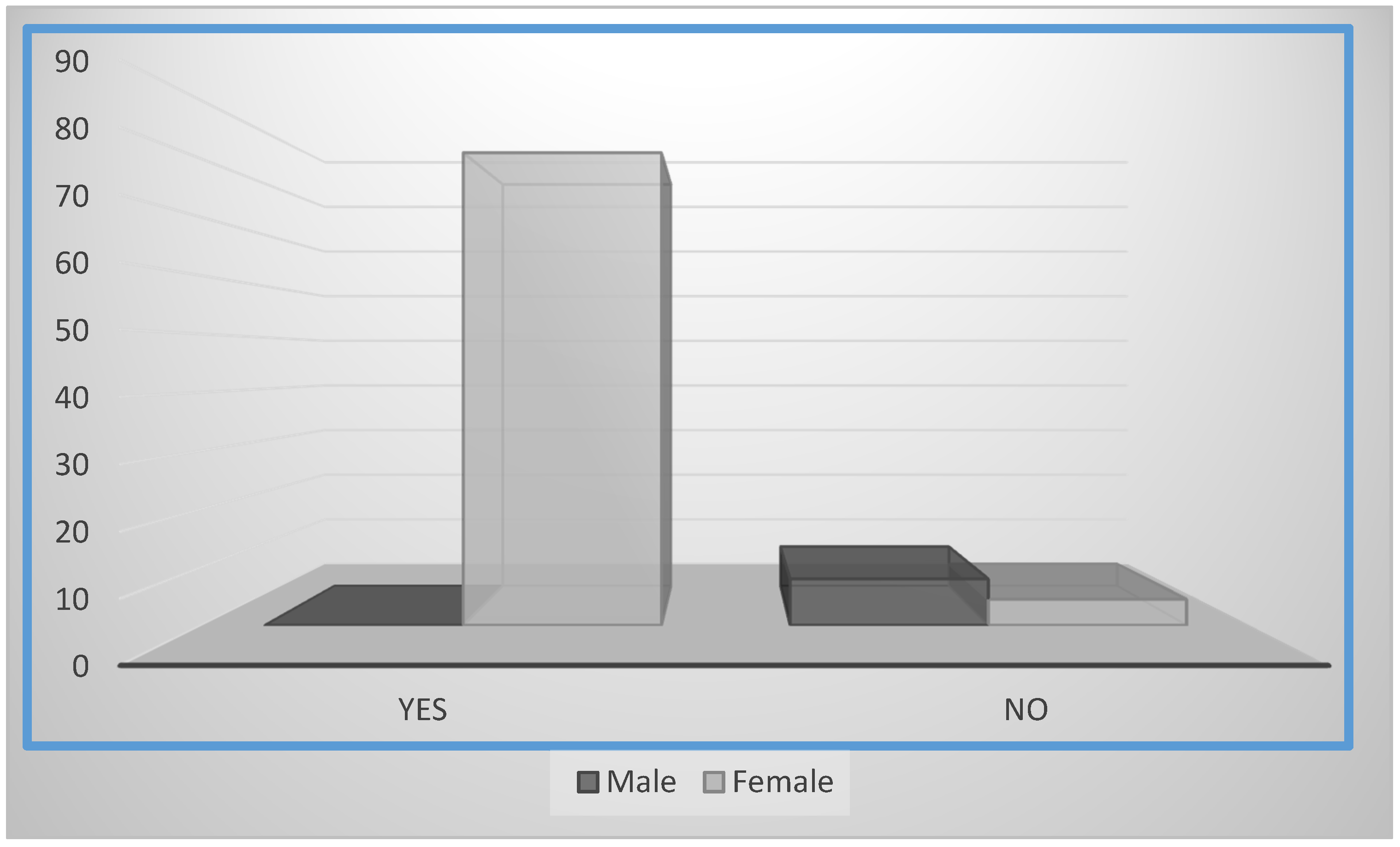

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Respondents

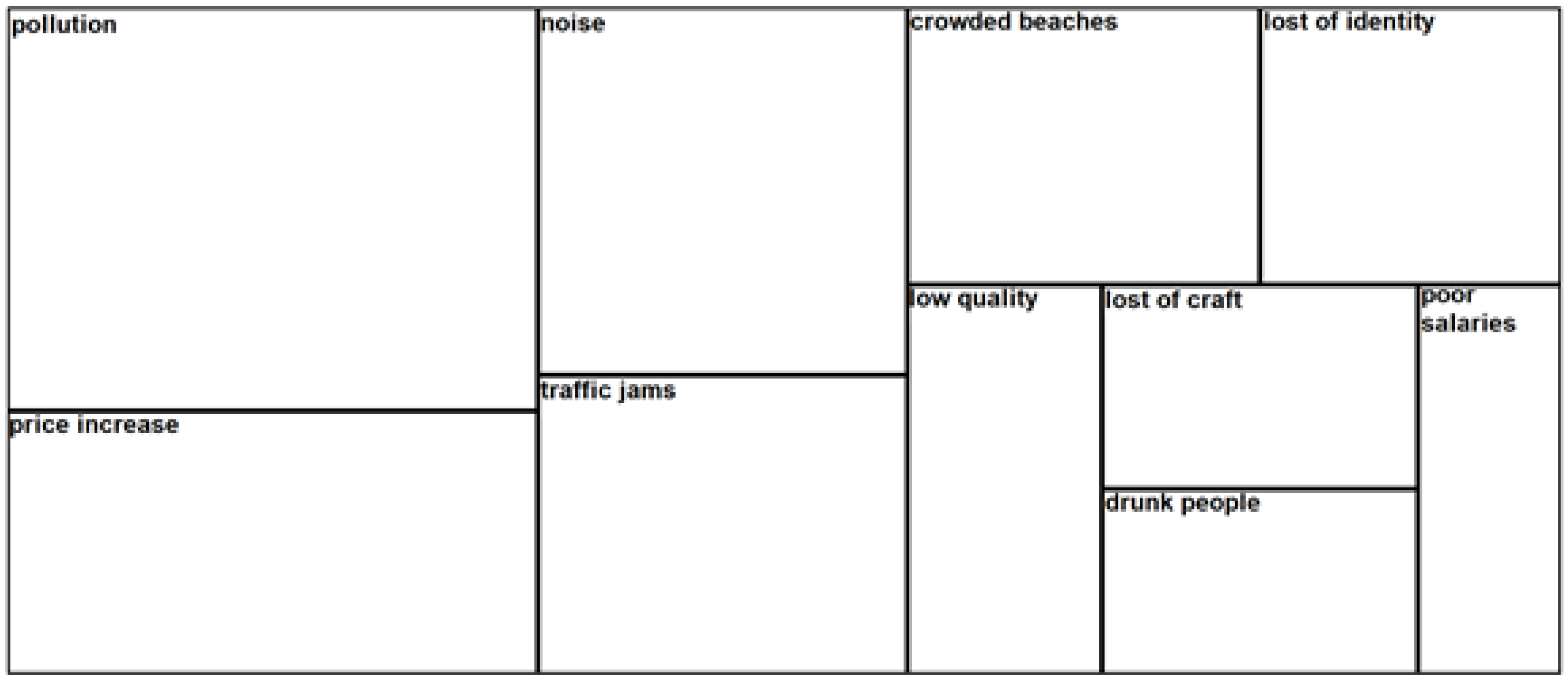

4.2. Impacts on the City of Málaga

4.3. Impacts on Local People

4.4. Specific Study about Impacts

4.4.1. Employment Impact

4.4.2. Impact on the Tourist Sector

4.4.3. Economic Impact

4.4.4. Environmental Impact

4.4.5. Improvement and Evaluation Comments for the Sustainable Development of the City at the Tourism Level

4.4.6. Impacts on Other Territories

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Travel and Tourism Council. 2020. Available online: https://www.wttc.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Tourism Industries Employment—Statistics Explained. Ec.europa.eu. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Tourism_industries_-_employment (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Theobald, W.F. Global Tourism; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- International Tourism Growth Continues to Outpace the Global Economy|UNWTO. Unwto.org. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-growth-continues-to-outpace-the-economy (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Air Transport and Tourism—Aena.es. Available online: http://www.aena.es/en/corporate/air-transport-tourism.html (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Dimitrios, D.; John, M.; Maria, S. Quantification of the air transport industry socio-economic impact on regions heavily depended on tourism. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 5242–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icao.int. 2020. Available online: https://www.icao.int/meetings/wrdss2011/documents/jointworkshop2005/atag_socialbenefitsairtransport.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Adding Value to the Economy. Aviationbenefits.org. 2020. Available online: https://aviationbenefits.org/economic-growth/adding-value-to-the-economy/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Inbound Tourism Worldwide by Mode of Transport 2018|Statista. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/305515/international-inbound-tourism-by-mode-of-transport/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Wergin, C. Book Review: Tourism and transport –modes, networks and flows (aspects of tourism texts) by David Timothy Duval. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2009, 2, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modul.ac.at. 2020. Available online: https://www.modul.ac.at/uploads/files/Theses/Bachelor/BYSYUK_Impact_of_9_11_on_US_and_International_Tourism_Development.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Spanish, C. BOE.es—Documento Consolidado BOE-A-1978-31229. BOE. 1978. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Transporte Aéreo y Turismo—Aena.es. Aena.es. 2020. Available online: http://www.aena.es/es/corporativa/transporte-aereo-y-turismo.html (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Ine.es. 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/daco/daco42/etr/etr0115_en.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Asían, R. ¿Terciarización de la economía andaluza? La estructura productiva andaluza y los servicios en la globalización. Reg. Stud. Mag. 2000, 58, 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Addie, J.P.D. Flying high (in the competitive sky): Conceptualizing the role of airports in global city-regions through ‘aero-regionalism’. Geoforum 2014, 55, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Ocupados por Sector Económico, Sexo y Comunidad Autónoma. Valores Absolutos(4228). 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=4228&L=0 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Corrales Pallavicini, J. Factors Influencing Tourism Destinations Attractiveness: The Case of Malaga. Master’s Thesis. 2020. Available online: https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/123456789/5538/Pallavicini,_Jazmin_Ariana_Corrales_1.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Un Centenar de Personas se Concentran en el Centro Contra el Turismo de Masas. Diario Sur. 2020. Available online: https://www.diariosur.es/malaga-capital/colectivos-concentran-malaga-20180927200236-nt.html (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Málaga Necesita un Acuerdo Sobre Turismo. Laopiniondemalaga.es. 2020. Available online: https://www.laopiniondemalaga.es/malaga/2020/05/03/malaga-necesita-acuerdo-turismo/1163348.html (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Sugiyarto, G.; Blake, A.; Sinclair, M.T. Tourism and globalization: Economic Impact in Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair-Maragh, G.; Gursoy, D.; Vieregge, M. Residents’ perceptions toward tourism development: A factor-cluster approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chien, H.; Cheng, H.; Chen, H. The Impacts of Tourism Development in Rural Indigenous Destinations: An Investigation of the Local Residents’ Perception Using Choice Modeling. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riet, A.V.; Berg, M.; Hiddema, F.; Sol, K. Meeting patients’ needs with patient information systems: Potential benefits of qualitative research methods. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2001, 64, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERIC—EJ800284—From the Outside Looking in: How an Awareness of Difference Can Benefit the Qualitative Research Process, Qualitative Report, 2008-Mar. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ800284 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Morse, J.; Field, P.A. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals; Sage Publications: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dicken, P. The Multiplant Business Enterprise and Geographical Space: Some Issues in the Study of External Control and Regional Development (Volume 10, Number 4, 1976). Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, S37–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, N.; Bråthen, S. Impact of airports on regional accessibility and social development. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, G. Transportation and tourism: A symbiotic relationship? In The Sage Handbook of Tourism Studies; Jamal, T., Robinson, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, Chapter 21; pp. 371–395.

- Lohmann, G.; Duval, D. Destination morphology: A new framework to understand tourism–transport issues? J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism and Air Transport (Contains papers in English and French)|World Tourism Organization. E-unwto.org. 2020. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284403691 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Andereck, K.L. Environmental consequences of tourism: A review of recent research. In Linking Tourism, the Environment, and Sustainability; McCool, S.F., Watson, A.E., Eds.; General Technical Report INT: Ogden, UT, USA, 1995; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, I.K.; Hitchcock, M. Local reactions to mass tourism and community tourism development in Macau. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.; Deidda, M.; Pulina, M. Tourism and transport systems in mountain environments: Analysis of the economic efficiency of cableways in South Tyrol. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, T.; Wittmer, A. Air transport and tourism—Perspectives and challenges for destinations, airlines and governments. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2006, 12, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Denstadli, J. Booming Leisure Air Travel to Norway—The Role of Airline Competition. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Denstadli, J. Norwegian business air travel–segments and trends. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2004, 10, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierczak-Korzeniowska, B. The history of tourist transport after the modern industrial revolution. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2011, 18, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremen, D.E. Inexpensive airlines—Development of regional tourism. In New Trends in Tourism Development; Gołembski, G., Ed.; PWSZ: Sulechów, Poland, 2008; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P.C. Atlantic Reverberations: French Representations of an American Presidential Election; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.R. Tourism and Transition: Governance, Transformation, and Development. 2004. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=VWsb148C1zAC&oi=fnd&pg=PA119&dq=%22strong+relationship+between+tourism%22&ots=b5os1JUX8&sig=XFQOKty4ndbTEnbDcnv9EwLDt_w#v=onepage&q=%22strongrelationshipbetweentourism%22&f=false (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Airport Categories Airports. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/airports/planning_capacity/passenger_allcargo_stats/categories/ (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Mindell, J. Changing aspirations: The future of transport and health. J. Transp. Health 2019, 15, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Mayer, T.; Walker, M.L.; Christison, E.L.; Johnson, D.G.; Matlak, M.E.; Storrs, B.B.; Clark, P. Air Transport of Pediatric Emergency Cases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982, 307, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jony, L.; Baskett, T.F. Emergency Air Transport of Obstetric Patients. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2007, 29, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupa, M. Air transport, aeronautic medicine, health. Bull. Acad. Natl. Med. 2009, 193, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeyratne, R.I.R. Management of the environmental impact of tourism and air transport on small island developing states. J. Air Transp. Manag. 1999, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.J.; Blom, H.A.P.; Lillo, F.; Mantegna, R.N.; Micciche, S.; Rivas, D.; Vazquez, R.; Zanin, M. Applying complexity science to air traffic management. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 42, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karppinen, N.; Lucas, A.; Ljungberg, M.; Repusseau, P. Artiicial Intelligence in Air Traac Flow Management; Australian Artificial Intelligence Institute: Cartlon, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, R.; Lohmann, G. The carrier-within-a-carrier strategy: An analysis of Jetstar. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2015, 42, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Fidato, A.; Humphreys, I. Airport-airline interaction: The impact of low-cost carriers on two European airports. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2003, 9, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, H.S.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Surucu-Balci, E.; Balci, G.; Zhou, Q. Airport selection criteria of low-cost carriers: A fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appold, S.J. The Impact of Airports on US Urban Employment Distribution. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J. The city-airport connection in the low-cost carrier era: Implications for urban transport planning. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2010, 16, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derudder, B.; Witlox, F.; Faulconbridge, J.; Beaverstock, J. Airline data for global city network research: Reviewing and refining existing approaches. GeoJournal 2008, 71, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, J.H.; Barnett, G.A.; Chon, B.-S. Comparing world city networks: A network analysis of Internet backbone and air transport intercity linkages. Glob. Netw. 2006, 6, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Timberlake, M.F. World City Networks and Hierarchies, 1977–1997. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 44, 1656–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derudder, B.; Devriendt, L.; Witlox, F. A spatial analysis of multiple airport cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K. Global city regions and the location of logistics activity. J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Government weakens airport noise standards. Science 1980, 207, 1189–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankford, S.V.; Howard, D.R. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilake, B.; Jayathilake, P.M.B. Tourism and Economic Growth in Sri Lanka: Evidence from Cointegration and Causality. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2013, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Macbeth, J.; Carson, D.; Northcote, J. Social capital, tourism and regional development: SPCC as a basis for innovation and sustainability. Curr. Issues Tour. 2004, 7, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. Tourism and regional development issues. Tour. Dev. 2002, 112–148. [Google Scholar]

- Saarinen, J. The regional economics of tourism in northern finland: The socio-economic implications of recent tourism development and future possibilities for regional development. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2003, 3, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrovski, D.D.; Todorović, A.T.; Valjarević, A.D. Rural Tourism and Regional Development: Case Study of Development of Rural Tourism in the Region of Gruţa, Serbia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 14, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derudder, B.; Wilcox, F. The Geographies of Air Transport. In Global Cities and Air Transport; Goetz, A.R., Budd, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, R.; Baker, D. Spatial Planning Models of Airport-Driven Urban Development. J. Plan. Lit. 2011, 26, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, R. Planning, sustainability and airport-led urban development. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; Dijst, M. Mobility environments and network cities. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, X.L.; Coto-Millán, P.; Díaz-Medina, B. The impact of tourism on airport efficiency: The Spanish case. Util. Policy 2018, 55, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus: Pérdidas en las Comunidades más Turísticas de España|Statista. 2020. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1108654/prevision-de-perdidas-en-el-sector-turistico-por-el-coronavirus-covid-19-en-espana/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Budd, L.; Bell, M.; Warren, A. Maintaining the sanitary border: Air transport liberalisation and health security practices at UK regional airports. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.D. Globalisation and psychiatry. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2003, 9, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Air Transport Action Group, Aviation Benefits Beyond Borders. 2018. Available online: https://aviationbenefits.org/media/166344/abbb18_full-report_web.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Lyons, K.; Young, T.; Hanley, J.; Stolk, P. Professional Development Barriers and Benefits in a Tourism Knowledge Economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 18, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.; Ivanov, S. Transforming competitiveness into economic benefits: Does tourism stimulate economic growth in more competitive destinations? Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppock, J. Leisure, tourism and social change. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R. Social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 5, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M. Polar tourism: An environmental perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 723–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splettstoesser, J.; Folks, M. Environmental guidelines for tourism in Antarctica. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B. Air Transport Policy: Reconciling Growth and Sustainability? In A New Deal for Transport: The UK’s Struggle with the Sustainable Transport Agenda; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration. The Economic Impact of Civil Aviation on the U.S. Economy; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 26.

- Flores, A.; Chang, V. Relación entre la demanda de transporte y el crecimiento económico: Análisis dinámico mediante el uso del modelo ARDL. Cuad. Econ. 2020, 43, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Passenger Air Lines. Science 1927, 65, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, A. World’s Largest Airlines? Proposed Merger of US Airways—American Airlines. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.; Sutandi, S. Analisa Rasio Keuangan Garuda Indonesia Airlines, Singapore Airlines Dan Thailand Airlines Dengan Uji Non-Parametrik (Periode: 2010–2014). eCo-Buss 2018, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, L. Airport Deregulation: Effects on Pricing and Capacity. SSRN Electron. J. 2007, 26, 1015–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, J. Aviation and tourism policies: Balancing the benefits. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mense, A.; Kholodilin, K. Noise expectations and house prices: The reaction of property prices to an airport expansion. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2014, 52, 763–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appold, S. Airport cities and metropolitan labor markets: An extension and response to Cidell. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 15, 1145–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, W. Impact of Privatization on Airport Performance: Analysis of Polish and British Airports. J. Int. Stud. 2009, 2, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Fadel, M.; Chahine, M. Case History: An assessment of the economic impact of airport noise emissions near Beirut International Airport. Noise Control Eng. J. 2002, 50, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouk, M.; Pagliari, D.; Moxon, R. The impact of national macro-environment exogenous variables on airport efficiency. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 82, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Cao, X.; Liu, J. Impact of atmospheric particulate matter pollutants to IAQ of airport terminal buildings: A first field study at Tianjin Airport, China. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 179, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Peng, W.; Hu, M. Airport noise and house prices: A quasi-experimental design study. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingwater, D. Aviation and sustainability. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2003, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.; Ülkü, T.; Yazhemsky, E. Small regional airport sustainability: Lessons from benchmarking. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 33, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.S. Trade and Transport Policy in Inclement Skies—The Conflict between Sustainable Air Transportation and Neo-Classical Economics. J. Air Law Commer. 1999, 65, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Upham, P. A comparison of sustainability theory with UK and European airports policy and practice. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 63, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A.R.; Graham, B. Air transport globalization, liberalization and sustainability: Post-2001 policy dynamics in the United States and Europe. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenley, C.A.; Machado, W.V.; Fernandes, E. Air transport and sustainability: Lessons from Amazonas. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Guyer, C. Environmental sustainability, airport capacity and European air transport liberalization: Irreconcilable goals? J. Transp. Geogr. 1999, 7, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 10561076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J.; Var, T.; Var, T. Resident attitudes to tourism in North Wales. Tour. Manag. 1984, 5, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastias-Perez, P.; Var, T. Perceived Impacts of Tourism by Residents. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Tourism’s Impacts: The Social Costs to the Destination Community as Perceived by Its Residents. J. Travel Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors Predicting Rural Residents’ Support of Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzanella, F. Perceptions and role of tourist destination residents compared to other event stakeholders in a small-scale sports event. The case of the FIS World Junior Alpine Ski Championships 2019 in Val di Fassa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantsperger, M.; Thees, H.; Eckert, C. Local participation in tourism development-roles of non-tourism related residents of the Alpine Destination Bad Reichenhall. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Peláez-Fernández, M.Á.; Balbuena-Vázquez, A.; Cortés-Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, K. Examining the power role of Local Authorities in planning for socio-economic event impacts. Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 2019, 34, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Inkari, M. Host community attitudes toward tourism and cultural tourism development: The case of the Lewes District, Southern England. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredline, L.; Deery, M.; Jago, L. A longitudinal study of the impacts of an annual event on local residents. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Porras, N.; Plaza, M.A. Residents; attitude to tourism and seasonality. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besculides, A.; Lee, M.; McCormick, P. Resident&perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 303–319. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, G.V. A Causation Theory of Visitor-Resident Irritants: Methodology and Research Inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Associations, Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar, R.; Hollier, R. Le Marketing Touristique; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aena. Aeropuerto Málaga_Costa del Sol—Aena.es. 2020. Available online: http://aena.mobi/m/es/aeropuerto-malaga/malaga-costa-sol.html (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- INE. Población por Comunidades y Ciudades Autónomas y Tamaño de los Municipios.(2915). 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2915#!tabs-tabla (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Suárez García, P. Población de Málaga (Provincia). 2020. Available online: https://padron.com.es/málaga/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- De Málaga, C.E. Invest in tourist sector in Malaga, most demanded tourist destination. Available online: https://forinvestormalaga.com/invest-in-malaga/activity-sectors/tourism/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Introducción al Aeropuerto de Málaga. 2020. Available online: http://www.aena.es/en/malaga-airport/introduction.html (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Gasto Medio Diario de Turistas Extranjeros Andalucía España 2019|Statista. 2020. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/477839/gasto-medio-diario-de-los-turistas-internacionales-en-andalucia/ (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Ruiz, E.C.; de la Cruz, E.R.R.; Vázquez, F.J.C. Sustainable tourism and residents’ perception towards the brand: The case of Malaga (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.M.S. Basic Guidelines for Research: An Introductory Approach for All Disciplines; Book Zone Publication: Chittagong, Bangladesh, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Estadísticas-Aeropuertos Españoles- aena.es, Aena. 2020. Available online: http://www.aena.es/csee/Satellite?pagename=Estadisticas/Home (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Arcury, T.; Christianson, E. Environmental Worldview in Response to Environmental Problems. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Sirakaya, E. Measuring Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Tourism: Development of Sustainable Tourism Attitude Scale. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, P.; Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Carter, J. Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, J.G.; García, F.P. Metodología y Medición del Impacto Económico de los Aeropuertos; Civitas: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Olipra, Ł. The impact of low-cost carriers on tourism development in less famous destinations. In Electronic Conference Proceeding: Il Valore Della Lentezza per il Turismo del Futuro; Cittaslow: Perugia, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fageda, X.; Jiménez, J.; Perdiguero, J. Price Rivalry In Airline Markets: A Study Of A Successful Strategy Of A Network Carrier Against A LowCost Carrier. Ub.edu. 2020. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/irea/working_papers/2010/201007.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2020).

| Geographical Area | The City of Málaga |

|---|---|

| Universe (Residents/International Tourists) | 571,026/129,678 |

| Sampling error | 3.14%/5% |

| Procedure | Simple random sample |

| Reliability | 90% |

| Fieldwork activities | May 2018–September 2019 |

| Málaga Costa Del Sol Airport (Arrivals) | Total | J | F | M | A | M | J | JUL | AG | S | O | N | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 129,678 | 2958 | 3453 | 5374 | 6846 | 6530 | 15,441 | 23,251 | 28,627 | 14,015 | 10,509 | 6749 | 5925 |

| Montreal Pierre Elliot Trudeau | 28,015 | 213 | 1094 | 2533 | 2883 | 2087 | 2544 | 3163 | 3374 | 2951 | 3879 | 2169 | 1125 |

| Casablanca Mohamed V | 23,645 | 1574 | 1245 | 1611 | 1768 | 1341 | 2191 | 2880 | 3624 | 1595 | 1990 | 1765 | 2061 |

| Marrakech Menara | 18,765 | 667 | 1000 | 1100 | 2785 | 2697 | 2627 | 2450 | 2700 | 2739 | |||

| New York John F. Kennedy Intl | 15,281 | 828 | 4262 | 4720 | 4989 | 482 | |||||||

| Hamad International | 15,083 | 97 | 2242 | 4347 | 5774 | 2623 | |||||||

| Tetuan Sania Ramel | 8377 | 1238 | 1037 | 1125 | 1463 | 1241 | 1234 | 1039 | |||||

| Tel Aviv Ben Gurion Int. | 5781 | 1009 | 1529 | 1224 | 1033 | 986 | |||||||

| Kuwait International | 4005 | 411 | 998 | 1829 | 767 | ||||||||

| Argel Houari Boumedien | 3381 | 334 | 294 | 318 | 290 | 140 | 260 | 545 | 685 | 350 | 165 | ||

| Tanger Boukhalef | 2605 | 766 | 820 | 912 | 107 | ||||||||

| Riyadh King Khaled Intl | 2484 | 142 | 529 | 1682 | 131 | ||||||||

| Bahrain International | 2070 | 155 | 292 | 1508 | 115 | ||||||||

| Bamako | 115 | 115 | |||||||||||

| Essaouira Mogador | 71 | 71 |

| Occupation | Gender | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALE | FEMALE | |||||

| Residents | Occupation | EMPLOYED BY OTHERS | Count | 121 | 247 | 368 |

| Occupation | 32.9% | 67.1% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 50.8% | 52.2% | 53.6% | |||

| SELF-EMPLOYED | Count | 16 | 69 | 85 | ||

| Occupation | 18.8% | 81.2% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 6.7% | 15.4% | 12.4% | |||

| UNEMPLOYED | Count | 16 | 67 | 83 | ||

| Occupation | 19.3% | 80.7% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 6.7% | 15% | 12.1% | |||

| STUDENT | Count | 38 | 57 | 95 | ||

| Occupation | 40.0% | 60.0% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 16% | 12.7% | 13.9% | |||

| RETIRED | Count | 40 | 15 | 55 | ||

| Occupation | 72.3% | 27.3% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 16.8% | 3.3% | 8% | |||

| Total | Count | 239 | 447 | 686 | ||

| Occupation | 34.9% | 65.2% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Tourists | Occupation | EMPLOYED BY OTHERS | Count | 72 | 51 | 123 |

| Occupation | 58.3% | 41.7% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 57.1% | 35.1% | 45.3% | |||

| SELF-EMPLOYED | Count | 30 | 31 | 61 | ||

| Occupation | 49.2% | 50.8% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 24.5% | 21.1% | 22.6% | |||

| UNEMPLOYED | Count | 0 | 20 | 20 | ||

| Occupation | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 0.0% | 14.0% | 7.5% | |||

| STUDENT | Count | 11 | 5 | 16 | ||

| Occupation | 66.7% | 33.3% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 8.2% | 3.5% | 5.7% | |||

| RETIRED | Count | 13 | 38 | 51 | ||

| Occupation | 25.0% | 75.0% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 10.2% | 26.3% | 18.9% | |||

| Total | Count | 126 | 145 | 271 | ||

| Occupation | 46.5% | 53.5% | 100.0% | |||

| % within Gender | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |||

| Word/Groups of Words | Length | Count by Answer | Weighted Percentage (%) | Similar Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of Travel | 12 | 299 | 21.00 | travel, journey, voyage, tours, flights, connections |

| Job | 3 | 180 | 8.18 | job, work, employment, opportunities |

| Economic | 8 | 106 | 4.82 | economy, money, wealth, profits, benefits |

| Total | 34.00 |

| Word/Groups of Words | Length | Count by Answer | Weighted Percentage (%) | Similar Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job | 3 | 103 | 53.21 | job, work, employment, opportunities |

| Economic | 8 | 92 | 26.79 | economy, money, wealth, profits, benefits |

| Total | 80.00 |

| Themes | Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | Quality Salary | “The residents and the tourist workers are friendly but inexperienced. Specialized courses should be offered to develop new management skills.” “Workers in the tertiary sector have precarious salaries and low-skilled.” “Frustration… A bottle of wine is more expensive than my salary.” |

| Airport | New routes New issuing countries | “Improve connections with Japan and the USA.” “Remove some low-cost routes. A tourist is good for the city but a rich tourist is better.” “There is a world to discover. For example, Saudi Arabia remains an untapped market.” “Low-cost is damaging the competitiveness of our tourist sector. We need quality, not quantity.” “To avoid the seasonality.” |

| Decentralization | Tourism Tourist Offer | “The interior of the province is more beautiful than the capital. It is worth visiting it.” “If you look for a destination, Málaga is the best one. The only snag is that they don’t know what they have. They should promote its brand within and outside its borders.” “Málaga needs to include wine tourism, agrotourism, and inland tourism in the tourist offer.” |

| Cleaning | Streets Beaches | “Sun and beach are not enough when your beaches are dirty.” “Streets need to be cleaned.” “The weather is perfect however the beaches are the worse in Andalusia...crowded beaches [..].” |

| Language | English | “I can’t understand how they don’t speak English.” |

| Environment | Polluting Emissions | “Cars should be electric. We would reduce greenhouse gas emissions” “The nearest area around the airport could be a great forest. Now, there are only cars and industrial warehouses” |

| New lines | Tourism products | “Some residents think we are looking for the same services as in the 90s.” “To continue with the idea of a new culture rebirth of the city should be a great step.” “In the historical centre, Larios Street has lost its identity. Traditional businesses and crafts were closed, and multinational brands dominate the street.” |

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 171 | 21.7 | 21.7 | 21.8 | |

| N Economic and Tourist I | 85 | 10.8 | 10.8 | 32.6 | |

| No effects | 119 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 47.7 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 18 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 49.9 | |

| Only Tourist Impacts | 7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 173 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 22.1 | |

| No effects | 170 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 43.6 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 50 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 49.9 | |

| Only Tourist Impacts | 7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Touristic I | 169 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 21.5 | |

| No effects | 198 | 25.1 | 25.1 | 46.6 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 18 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 48.9 | |

| Only Tourist Impacts | 15 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 283 | 35.9 | 35.9 | 36.0 | |

| N Economic and Tourist I | 28 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 39.5 | |

| No effects | 47 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 45.5 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 42 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 253 | 32.1 | 32.1 | 32.2 | |

| N Economic and Tourist I | 17 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 34.3 | |

| No effects | 87 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 45.4 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 33 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 49.6 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 398 | 50.4 | 50.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 241 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 30.7 | |

| N Economic and Tourist I | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 31.2 | |

| No effects | 113 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 45.5 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 42 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| P Economic and Tourist I | 197 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.1 | |

| N Economic and Tourist I | 25 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 28.3 | |

| No effects | 145 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 46.6 | |

| Only Economic Impacts | 33 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 50.8 | |

| Do not know/Do not answer | 388 | 49.2 | 49.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 789 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero Galeote, L.; García Mestanza, J. Qualitative Impact Analysis of International Tourists and Residents’ Perceptions of Málaga-Costa Del Sol Airport. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114725

Caballero Galeote L, García Mestanza J. Qualitative Impact Analysis of International Tourists and Residents’ Perceptions of Málaga-Costa Del Sol Airport. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114725

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero Galeote, L., and J. García Mestanza. 2020. "Qualitative Impact Analysis of International Tourists and Residents’ Perceptions of Málaga-Costa Del Sol Airport" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114725

APA StyleCaballero Galeote, L., & García Mestanza, J. (2020). Qualitative Impact Analysis of International Tourists and Residents’ Perceptions of Málaga-Costa Del Sol Airport. Sustainability, 12(11), 4725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114725