Dynamic Coordination of Internal Displacement: Return and Integration Cases in Ukraine and Georgia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Theoretical Background

4. Results: Coordination Dynamics of Internal Displacement

- (1)

- Bistability—regarding the internal displacement due to the Russo-Georgian wars of 1992 and 2008, followed by the ethno-focal issues on the agenda of the de facto administrations of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and the intensive official rhetoric of IDPs’ return in Georgian and international discourses;

- (2)

- Metastability—the internal displacement triggered by the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine between Ukrainian military forces and Russian military forces backing the separatist administrations, as well as by the Russian occupation of Crimea; both the return and local integration scenarios are present in the practical discourses.

- (1)

- A non-equilibrium phase of eviction/displacement/resettlement leads to a perturbation of the social links and the actualization of the forced/voluntary movement attractor, this being regarded as the first stage of the decision-making sequence characterized by the intention, confidence, and success of a trial, which can further influence the decisions and is reflected in further attitudes regarding the return (it can be both a successful and a failed trial scenario, depending on the intention and sense of belonging) or the persistent integration into the local community.

- (2)

- Fluctuations take place when the system becomes unstable due to the displaced population influx into local communities. The bistability of the system means that two coordinated states coexist, for instance, return and integration, though there is a schismogenesis-like pressure aimed at promoting one of the options (e.g., obligatory/necessary return), which is absorbed by the system as a pattern. In this situation, practical discourses lead to a decision-making “prolapse,” when the displacement is considered a temporary state, regardless of its actual duration in decades. Thus, the adaptation and normalization of life under the current conditions become problematic. Multistability implies a coexistence of various scenarios and allows for switching between them. For instance, it can be traced in the economic-driven quasi-displacement of “hybrid IDPs.” Therefore, conflict-affected persons can abort a full displacement scenario due to the lack of confidence in the successful trial, or fear of the financial or social obstacles to displacement;

- (3)

- A durable quasi-stable stage of protracted internal displacement can be described as metastability. On the one hand, in the theory of dynamic coordination of brain and cognition, it implies “the simultaneous realization of two competing tendencies: the tendency of the individual components to couple together and the tendency for the components to express their independent behavior” [17] (p. 913); on the other hand, in the social perspective, there tends to form a “small-world”-like topology, including rather distinct groups with a potential of counteracting excessive convergence.

5. Internal Displacement in Georgia Due to Russia-backed Separatism (1992; 2008): Bistability Pattern of Resettlement

- (1)

- early 1990s: 60,000 displaced persons due to the 1989–1992 war in South Ossetia, i.e., the displacement accompanied with ethnical cleansings; over 250,000 persons affected by the 1992–1993 war in Abkhazia;

- (2)

- early 2000s: August 2004–government-supported relocation of women and children from the ethnic Georgian villages in South Ossetia; August 2008–158,000 displaced persons, Georgians and Ossetians [64] (p. 16).

- (1)

- The Georgian government stresses the necessity for the IDPs of all the displacement waves to return to their homes, as Abkhazia and South Ossetia are regarded as the territories meant to be under Georgian control. Local integration of the IDPs is on the agenda as a temporary solution, still compatible with further return [61,64,67].

- (2)

- For Abkhazia’s de facto administration, the return of IDPs is considered problematic, if possible. There is a negative attitude to Georgians, as well as the demands of the administration that the returnees give up their Georgian citizenship and obtain the local “passport,” thus hindering the IDP reintegration process [61,64,67]. Moreover, in the so-called “Law of the Republic of Abkhazia on Citizenship of the Republic of Abkhazia,” in Article 6, there are the provisions stating that dual citizenship is only possible for the citizens of the Russian Federation [68].

- (3)

- South Ossetia’s de facto administration has adopted an ambiguous approach to returnees: after the war, return was declared impossible. Later, nevertheless, the rhetoric changed, and the right to return was formally acknowledged, though the practical implementation of reintegration did not follow [64] (p. 47). At the same time, the integration with the Russian Federation widened. For instance, on December 28, 2018, in the Law on the Amendment to the Treaty on alliance and integration between the Russian Federation and the Republic of South Ossetia, the absence of limitations for the period of stay of the citizens of the Russian Federation in the self-proclaimed republic was ratified [69]. And in the so-called “Law of the Republic of South Ossetia on Citizenship of the Republic of South Ossetia”, in Article 16, the grounds for refusal to grant citizenship of the Republic of South Ossetia include the position of a person against the sovereignty of South Ossetia, as well as a citizenship of another state other than South Ossetia or the Russian Federation [70].

6. Internal Displacement in Ukraine Due to Russian Military Aggression (2014-Present): Metastability Pattern of Resettlement

- (1)

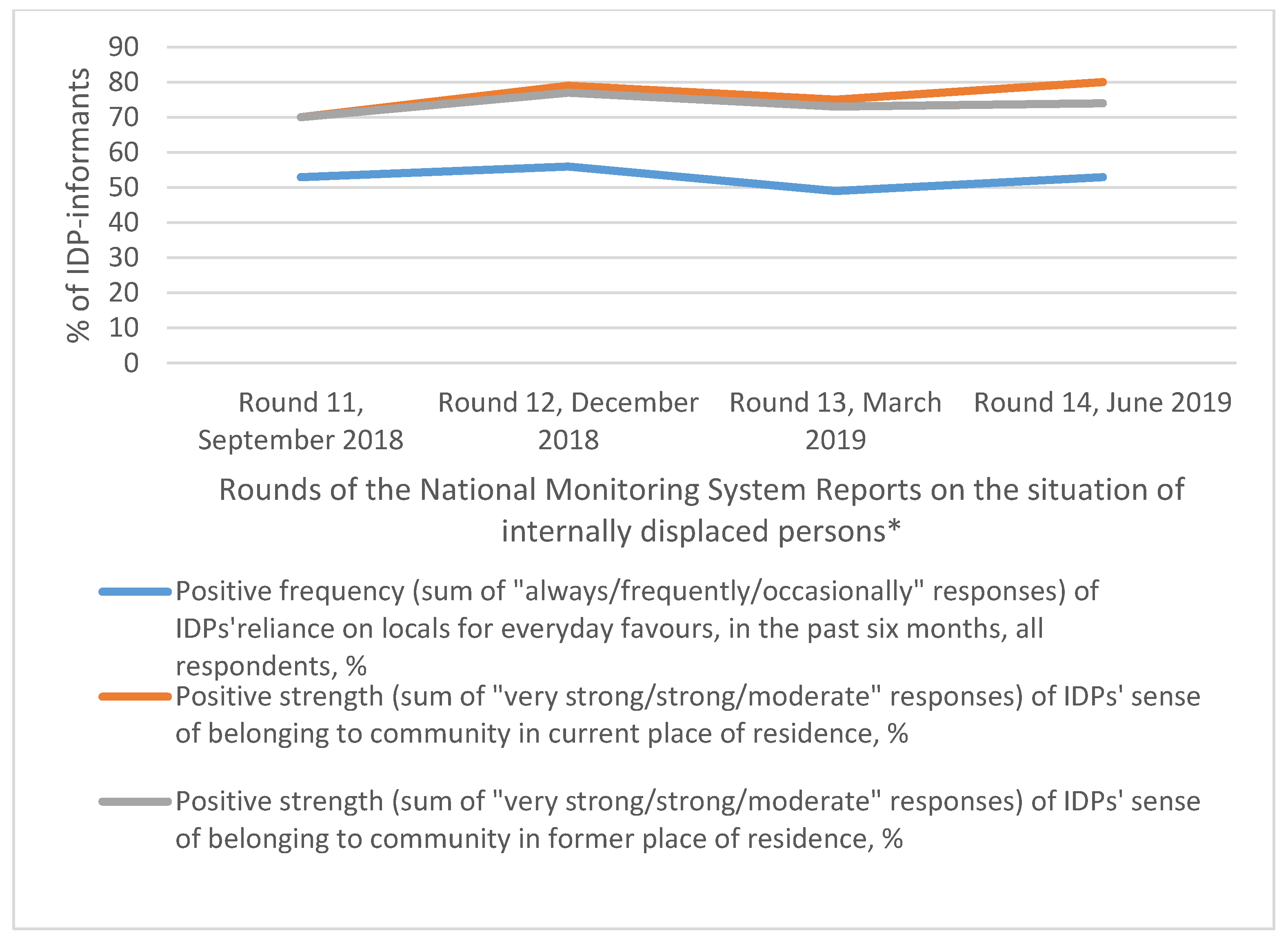

- The IDP group’s members are considered “both victims and perpetrators” [14] (p. 27); due to the prejudices concerning the accentuated image of those able to transfer the social order of the Donbas, the latter are believed to be criminally threatening to the host communities; the stigmatization of the IDPs from the Donbas, “not able to defend Ukraine,” in some cases lead to the silencing of the separatist past [14,15]. Nevertheless, the results of the National Monitoring System Reports (NMS reports) on the situation of internally displaced persons, in 2019, demonstrated a high level of trust placed on the IDPs by the local population, reaching 61% [51] (p. 46). Up to 22%–23% of IDP-informants intended to return to the former place of residence in the future, compared with 34%–36% who had no intention to return even after cessation of the conflict [50,51].

- (2)

- The “burden of survival” and “contamination” with the region of earlier residence [14] (p. 58), as well as the life-death experience of war-fleeing survivors, caused the pattern of firstly positive generalization toward the group in the receiving communities to change to negative assumptions and prejudices, and led to the invisibility or further exclusion of the migration-specific issues from the agendas [15] (pp. 51–54). The same pattern can be traced in the case of Ukrainian refugees in the Russian Federation, from help and consolidation, in 2014, to resentment, in 2015 [57] (pp. 105–107). Even the traditionally supportive communities of the GCA of the Donetsk region, with the highest density of internally displaced populations, showed a drop in positive attitude toward the IDPs, from 7.9 to 7.5 points, in 2017-2018 [81]. There was also a decrease in contacts between the local population and IDPs in the Luhansk region of the GCA, from 4.6 to 3.9 points, in 2017-2018 [81], but this tendency might indicate the assimilation and, therefore, the invisibility of the IDP group in the communities, and not a widening of the gap between the locals and the newcomers.

- (3)

- “Marker of displacement” in social services, following the Resolutions of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, highlighting the necessity of regular physical checks on IDPs and their living conditions in order to obtain benefits and payments [83]. It should also be taken into consideration the criminalizing of IDPs in the mass media, especially during the early stage of displacement, and further otherness grading, with different attitudes to the IDPs from Crimea and the Donbas in the receiving communities [14,15,58].

- (4)

- Invisibility of the IDPs in the communities where their percentage is low and exclusion from decision-making; readiness of the current authorities in Ukraine for decisions leading to ambivalent consequences, and therefore able to “seduce Russia and the West to press Kyiv for concessions” [84] (p. 702).

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- integration mode: sense of belonging to the current place of residence; IDP-status being irrelevant; groups involved—IDPs with a negligible possibility/intention of return, integrated/reintegrated populations; coordination model–monostability;

- (2)

- return mode: “necessary/rightful/dignified/safe return” of the IDPs to the former place of residence as the only solution and desired outcome promoted in the official discourses; sense of belonging to the former place of residence in the conflict-affected areas; groups involved–“temporarily” displaced persons, shuttling IDPs; coordination model–bistability;

- (3)

- IDP-status mode: ambiguous quasi-stable state without preferable solutions; both integration in the local community and return are supported in legislation; groups involved–IDPs, local communities, official bodies promoting representation and participation of IDPs in decision-making; coordination model–metastability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- USAID. Ukraine-Conflict Fact Sheet #1; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ukraine_fs01_11-19-2015.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- USAID. Ukraine-Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #2; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ukraine_ce_fs02_06-24-2019.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2020; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_assistance_report_december_2019_-january_2020_eng.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- The Difficulties of Counting IDPs in Ukraine; Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID); Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2018/downloads/report/2018-GRID-spotlight-ukraine.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2020).

- Schoen, D.E.; Kaylan, M. Return to Winter: Russia, China, and the New Cold War against America; Encounter Books: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, N. Ukraine and the Minsk II Agreement: On a Frozen Path to Peace? European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/573951/EPRS_BRI(2016)573951_EN.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Dempsey, J. Judy Asks: Can the Minsk Agreement Succeed? A Selection of Experts Answer a New Question from Judy Dempsey on the Foreign and Security Policy Challenges Shaping Europe’s Role in the World; Carnegie Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/68084 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Malyarenko, T.; Wolff, S. The logic of competitive influence-seeking: Russia, Ukraine, and the conflict in Donbas. Post-Sov. Aff. 2018, 34, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelles, M. Expert Q&A: Will the Steinmeier Formula Bring Peace to Ukraine? Atlantic Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/expert-qa-will-the-steinmeier-formula-bring-peace-to-ukraine/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Van Puyvelde, D. Hybrid War–Does It Even Exist? NATO Review. 7 May 2015. Available online: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2015/05/07/hybrid-war-does-it-even-exist/index.html (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Dodonov, R.; Kovalskyi, H.; Dodonova, V.; Kolinko, M. Polemological Paradigm of Hybrid War Research. Philos. Cosmol. 2017, 19, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Grzymala-Kazlowska, A.; Phillimore, J. Introduction: Rethinking integration. New perspectives on adaptation and settlement in the era of super-diversity. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, D.L.; Berry, J.W. Acculturation: When Individuals and Groups of Different Cultural background Meet. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivashchenko-Stadnik, K. The social challenge of internal displacement in Ukraine: The host community’s perspective. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis. A Two-Country Perspective; Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A., Uehling, G., Eds.; E-International Relations Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bulakh, T. ‘Strangers among ours’: State and civil responses to the phenomenon of internal displacement in Ukraine. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis. A Two-Country Perspective; Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A., Uehling, G., Eds.; E-International Relations Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Ning, Y. Social Impacts of Dam-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: A Comparative Case Study in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelso, S.J.A. Multistability and metastability: Understanding dynamic coordination in the brain. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insabato, A.; Pannunzi, M.; Rolls, E.T.; Deco, G. Confidence-Related Decision Making. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranyushkin, D. Metastability of Cognition in Body-Mind–Environment; Network Version; Nodus Labs: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://noduslabs.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Metastability-Cognition.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Cavalli, F.; Naimzada, A. Complex dynamics and multistability with increasing rationality in market games. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2016, 93, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranyushkin, D. Identifying the Pathways for Meaning Circulation Using Text Network Analysis; Network Version; Nodus Labs: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/97ba/9f29c55ccbdd963e01f98cf17e73998f0f7d.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- EESC. Press Release: 2618th Council Meeting Justice and Home Affairs; EESC: Brussels, Belgium, 2004; Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/jha/82745.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Ferguson, N. The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for the Global Power; Allen Lane, an Imprint of Penguin Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Liquid Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Mobilities; Polity Press: Cambridge-Malden, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Runaway World: How Globalization Is Reshaping Our Lives; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, S. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2007, 30, 1024–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.; Strang, A. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. J. Refug. Stud. 2008, 21, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, M. Super-diversity vs. assimilation: How complex diversity in majority–minority cities challenges the assumptions of assimilation. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2016, 42, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiou, A.; Lancelin, A. Pokhvala Politytsi (Éloge de la Politique); Repa, A., Ed.; Nika-Centre: Kyiv and Lviv, Ukraine, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cottyn, I. Livelihood Trajectories in a Context of Repeated Displacement: Empirical Evidence from Rwanda. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y. Theory Reflections: Cross-Cultural Adaptation Theory; Association of International educators NAFSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.nafsa.org/sites/default/files/ektron/files/underscore/theory_connections_crosscultural.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- The Concept of the National Program appointed to deal with the consequences of the Chornobyl NPP accident and social defense of the citizens for the period of 1994-1995, and till 2000; Resolution of Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine; # 3422-XII; Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 1993. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/3421-12 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On the Legal Regime of the Territory Exposed to the Radioactive Contamination Resulting from the Chornobyl NPP Accident; Law of Ukraine No. 791a-XII; Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2016. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/791%D0%B0-12 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On the State Plan of Economic and Social Development of the Ukrainian SSR in 1987; Regulation of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR # 400; the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR: Kyiv, the Ukrainian SSR, 1986. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/400-86-%D0%BF/sp:max100 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On Resettlement of the Citizens of Two Settlements of Polesskii Region of Kyiv Oblast and 12 Settlements of Narodychskii Region of Zhytomyr Oblast Exposed to the Radioactive Contamination Resulting from the Chornobyl NPP Accident; Regulation of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR # 224-r; the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR: Kyiv, the Ukrainian SSR, 1989. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/224-89-%D1%80 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On Status and Social Defense of the Citizens Affected by the Chornobyl NPP Accident; Law of Ukraine # 796-XII; Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/796-12 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Ukraine. Recovery and Peacebuilding Assessment. Analysis of Crisis Impacts and Needs in Eastern Ukraine; Synthesis Report; EU: Brussels, Belgium; UN: New York, NY, USA; WBG: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 1, Available online: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/V1-RPA_Eng_rev2.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2014; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_idps_assistance_report_december_2014_4.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2015; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_idp_assistance_report_november_2015.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On Approval of the Concept of the Targeted State Program for Recovery and Peacebuilding in the Eastern Regions of Ukraine; Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, No. 892-r; the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2016. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/892-2016-%D1%80 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2016; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_assistance_report_november_-december_2016_english.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On Approval of the Strategy of Integration of Internally Displaced Persons and Implementation of Long-Term Solutions to Internal Displacement until 2020; Regulation of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, No. 909-r; the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2017. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/909-2017-%D1%80 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_assistance_report_november-december_2018_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_assistance_report_june-july_2019_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_assistance_report_september_2019_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- IOM’s Assistance to Conflict-Affected People in Ukraine; Bi-Monthly Report; IOM/Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_ukraine_assistance_report_november-october_2019_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons; Round 11; IOM: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018; Available online: https://displacement.iom.int/system/tdf/reports/nms_round_11_eng_press.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=4964 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons; Round 12; IOM: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/nms_round_12_eng_screen.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons; Round 13; IOM: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/nms_round_13_eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- National Monitoring System Report on the Situation of Internally Displaced Persons; Round 14; IOM: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: http://iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/nms_round_14_eng_web.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Sabates-Wheeler, R. Mapping differential vulnerabilities and rights: ‘opening’ access to social protection for forcibly displaced populations. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, M.; Burger, M.M. Unsuccessful Subjective Well-Being Assimilation among Immigrants: The Role of Faltering Perceptions of the Host Society. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M. The Impact of Armed Conflict on Displacement; Technical Report; Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, S.G. Internal Displacement and Conflict: The Kashmiri Pandits in Comparative Perspective; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smal, V. A Great Migration: What is the Fate of Ukraine’s Internally Displaced Persons. A dataset on internally displaced persons from the Crimea and Donbass. Vox Ukraine. 2016. Available online: https://voxukraine.org/en/great-migration-how-many-internally-displaced-persons-are-there-in-ukraine-and-what-has-happened-to-them-en/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Mukomel, V. Migration of Ukrainians to Russia in 2014–2015. Discourses and Perceptions of the Local Population. In Migration and the Ukraine Crisis. A Two-Country Perspective; Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A., Uehling, G., Eds.; E-International Relations Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Dodonova, V.; Dodonov, R. Monologues on the Donbas. Selected Works on the Conflict in Eastern Ukraine; Vydavets Ruslan Khalikov: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Attitudes of the Population of Ukraine towards IDPs; Press-Release on the Public-Opinion polls 2015–2018; Monitoring Results by the Institute of Sociology; National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Kiev, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: https://dif.org.ua/article/stavlennya-naselennya-ukraini-do-vnutrishno-peremishchenikh-osib (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Foreign Ministry Comment on Statements by Georgia and Ukraine Regarding the Anniversary of August 2008 Events. The official Site of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. 12 August 2016. Available online: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/2391051?p_p_id=101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw&_101_INSTANCE_cKNonkJE02Bw_languageId=en_GB (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- General Assembly Adopts Text on Status of Georgia’s Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons, Calls upon Participants in Geneva Discussions to Intensify Efforts. General Assembly Adopts Text on Status of Georgia’s Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons, Calls upon Participants in Geneva Discussions to Intensify Efforts. General Assembly Plenary Seventy-third Session. In Proceedings of the 88th Meeting (PM) GA/12151, New York, NY, USA, 4 June 2019; Available online: https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/ga12151.doc.htm (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Roudik, P. Georgia; Russian Federation: Separatist Regions of Georgia Conclude Military Agreements with Russia; Library of Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/law/foreign-news/article/georgia-russian-federation-separatist-regions-of-georgia-conclude-military-agreements-with-russia/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- A Heavy Burden-Internally Displaced in Georgia: Stories from Abkhazia and South Ossetia; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: http://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2008-eu-georgia-heavy-burden-country-en%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Georgia: IDPs in Georgia still need attention. A Profile of the Internal Displacement Situation; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/georgia/georgia-idps-georgia-still-need-attention (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Georgia: Partial Progress towards Durable Solutions for IDPs; Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: http://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/georgia-overview-mar2012.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement; UN (OCHA): New York, NY, USA, 1998; (updated 2004); Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/idps/43ce1cff2/guiding-principles-internal-displacement.html (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Special Abkhazia Issue: Ten Years after the War Report from Institute for War and Peace Reporting; IWPR: London, UK, 2002; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/georgia/special-abkhazia-issue-ten-years-after-war (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Law of the Republic of Abkhazia on Citizenship of the Republic of Abkhazia. 2005. Available online: http://www.emb-abkhazia.ru/konsulskie_voprosy/zakon_j/ (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Law of the Republic of South Ossetia on Amendment to the Treaty on Alliance and Integration between the Russian Federation and the Republic of South Ossetia. 2018. Available online: http://www.parliamentrso.org/node/2287 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Law of the Republic of South Ossetia on Citizenship of the Republic of South Ossetia. 2008. Available online: http://www.parliamentrso.org/node/85 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- On Some Issues of Social Benefits for Internally Displaced Persons; The CMU Resolution # 365; the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/365-2016-%D0%BF#n33 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Law of Ukraine on Provision Rights and Freedoms of Internally Displaced Persons. # 1706-VII; the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2020. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1706-18 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Background: Six-Point Peace Plan for the Georgia-Russia Conflict; Report; Deutsche Presse Agentur: Hamburg, Germany, 2008; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/georgia/background-six-point-peace-plan-georgia-russia-conflict (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Orzechowski, M. Conflicts in Donbass and the Kerch Strait as an Element of the Neo-Imperialist Expansion Strategy of the Russian Federation in the Post-Soviet Area. Ukr. Policymak. 2018, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidential Decree on Recognizing of the Republic of Crimea Independence. #147. 2014. Available online: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/38202 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Presidential Decree on Recognizing of the Republic of South Ossetia Independence. # 1261. 2008. Available online: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/27958 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Presidential Decree on Recognizing of the Republic of Abkhazia Independence. 2008. # 1260. 2008. Available online: http://kremlin.ru/acts/bank/27957 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Treaty of Alliance and Strategic Partnership between the Russian Federation and Republic of Abkhazia. 2014. Available online: http://kremlin.ru/supplement/4783 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Public Opinion Survey to Assess the Changes in Citizens’ Awareness of Civil Society and Their Activities; USAID/Kyiv: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018; Available online: https://dif.org.ua/uploads/pdf/3235987555af01ce0267550.88880763.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Public Opinion Survey to Assess the Changes in Citizens’ Awareness of Civil Society and Their Activities; USAID/Kyiv: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; Available online: https://dif.org.ua/uploads/pdf/1820094705d9ccb76b43dc5.92039369.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- 2017–2018 Main Changes. UN SCORE for Eastern Ukraine; UN Office in Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018; Available online: https://use.scoreforpeace.org/files/publication/pub_file//Trends2018_UA.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Bazaluk, O. The Problem of War and Peace: A Historical and Philosophical Analysis. Philos. Cosmol. 2017, 18, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- The CMU Resolution “Some Issues of Social Benefits for Internally Displaced Persons”. # 365; the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/365-2016-%D0%BF#n33 (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Haran, O.; Yakovlyev, M.; Zolkina, M. Identity, war, and peace: Public attitudes in the Ukraine-controlled Donbas. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2019, 60, 684–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinchenko, S. Mythologeme-Related Crisis of Identity: Reality and Fictional Markers of Alienation. Future Hum. Image 2019, 11, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals: Ukraine; National Baseline Report; Ministry of Economic Development and Trade of Ukraine: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2017; Available online: http://www.un.org.ua/images/sdgs_nationalReportEN_Web.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bazaluk, O.; Balinchenko, S. Dynamic Coordination of Internal Displacement: Return and Integration Cases in Ukraine and Georgia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104123

Bazaluk O, Balinchenko S. Dynamic Coordination of Internal Displacement: Return and Integration Cases in Ukraine and Georgia. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104123

Chicago/Turabian StyleBazaluk, Oleg, and Svitlana Balinchenko. 2020. "Dynamic Coordination of Internal Displacement: Return and Integration Cases in Ukraine and Georgia" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104123

APA StyleBazaluk, O., & Balinchenko, S. (2020). Dynamic Coordination of Internal Displacement: Return and Integration Cases in Ukraine and Georgia. Sustainability, 12(10), 4123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104123