1. Introduction

Social farming (SF) is an umbrella term that includes a broad variety of interventions such as social and worker inclusion, therapeutic horticulture, nature-based rehabilitation, and animal-assisted intervention in farms [

1]. Many research publications show that there is a wide range of activities and practices that have in common the use of natural elements to maintain and promote physical, mental, and social well-being [

2]. The concept of SF is used to describe the links between agricultural work and the provision of health and human services [

3] and, at the same time, to focus on conducting occupational activities and achieving employment goals at real production farms [

4]. In SF, a series of activities are carried out in the context of agricultural and natural environments to produce benefits for people at risk of social exclusion, including migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers [

1].

As will be specified in the following sentence, the variety of interventions depends on the territorial specificities (needs and resources) and opportunities, including policies and legislative frameworks. In Italy, SF is born as a possibility to include vulnerable people in agricultural activities addressed in real production farms. There are two main models of SF in the EU: the Northern European Specialised Model of Social Farming based on the framework of the “social-democratic” welfare system and within the market/state divide, and the Mediterranean Communitarian Model of Social Farming that is based on being organized within the framework of a welfare system, influenced by the support of families, civil society, and the so-called core economy [

5]. In particular, the Italian model is defined as inclusive [

6,

7]. The paths of social and working inclusion are realized using different means and policies instruments, such as traineeship and stages.

As for the recipients, Italian SF is aimed at different target groups: people with physical or psychic disabilities, prisoners, drug addicts, the young people neither in employment nor in education or training (NEETS), and the elderly [

6]. With the increase of the migration phenomenon, many interventions of SF are also aimed at refugees and asylum seekers [

8]. The agricultural sector plays a central role in the most recent migration processes, involving thousands of people arriving on the peninsula with the intention of staying or transiting to northern Europe. The effects of this phenomenon are direct on sectoral competitiveness, food security, and the economic and social development of rural areas in both countries of origin and destination.

Rural Europe faces these significant challenges: one of the five objectives of the Europe 2020 strategy is fighting against poverty and marginalization, with special attention to active inclusion in society and the labor market of the most vulnerable groups, by overcoming discriminations and fostering the integration of people with disabilities, ethnical minorities, immigrants, and other vulnerable groups [

9].

There is relevant literature that has analyzed the ways in which migrant labor has fit into the existing socio-economic and productive systems in rural southern Europe. Some examples include analyses conducted for rural areas in Italy [

10], Spain [

11,

12], Greece [

13,

14], Sweden [

15], and, more recently, Poland [

16].

As described above, the South European model of integration is different from the typical model of Central-Northern Europe [

17]. In detail, the integration of immigrants into the Italian labor market is characterized by a

net trade-off: on the one hand, a relatively low risk of unemployment; on the other hand, the risk of being placed in jobs of poor quality and stability [

18].

In general, the studies have focused on to the forms of labor (i.e., regulated and non-regulated, the role of

caporalato or other forms of intermediation), contractual rights, protections and exploitation [

19,

20,

21], cultural and social integration of immigrants [

22,

23], or the role of migrants in rural areas [

24]. However, the specific studies on SF addressed to the social and working inclusion of immigrants are few, although there is a presence of significant experiences [

25,

26].

This article analyses four Italian SF cases with the purpose of understanding the main drivers that facilitate or hinder the social and worker inclusion of immigrants in agricultural experiences. In the first part, the paper briefly describes the analytic model of social and working inclusion [

6]. Afterwards, the contribution describes the four case studies and analyzes them in relation to the analytic model. In conclusion, the article presents some suggestions in terms of recommendations for the policy and the implementation of the activities.

2. What Characteristics Should Have Social Farming to Be Inclusive?

The concept of inclusion is widespread in many fields of economic, political, sociological, anthropological, or ethical study. Its importance as a topic goes back to policy in the 1990s addressed to reduce social exclusion for disadvantaged or marginalized populations [

27,

28]. The European Union, especially between the 1970s and the 1990s, promoted the inclusion/exclusion idea through the financing of local projects and research. The concepts included several areas such as employment, housing, disability, education, rights of citizenship, and became enshrined in European policies.

Nevertheless, inclusion is a debated concept: it generally means that all people, regardless of their disabilities, religions, origins, sexual orientations or other differences, have the right to be respected and appreciated as valuable members of communities, attend education classes, work at jobs in the community that pay a competitive wage and have careers based on their capacities [

29,

30]. Different attributes can specify the means, mainly with regard to the proposed interventions to face exclusion situations, such as actions for improving the accessibility to public and private services and by the empowerment of the socially weaker parts [

30].

However, the inclusion is never absolute, but it is closely related to individuals and their perception, awareness, and knowledge of the situation, to the life phase, the specific context or the historical period, and the society’s framework conditions, such as its laws, regulations, and norms. It may concern only an area of life, such as employment, or all life aspects. Being influenced by a range of factors [

31,

32], social inclusion can be considered a dynamic construct. Accordingly, socially inclusive interventions should put the emphasis also on the native-born and their groupings, as well as on the inclusion of the socially weaker parts of them. It has come to be associated with connectedness, belonging as well as aspects of rights, entitlement, and social capital, taking a different shape depending on the context and the population [

32].

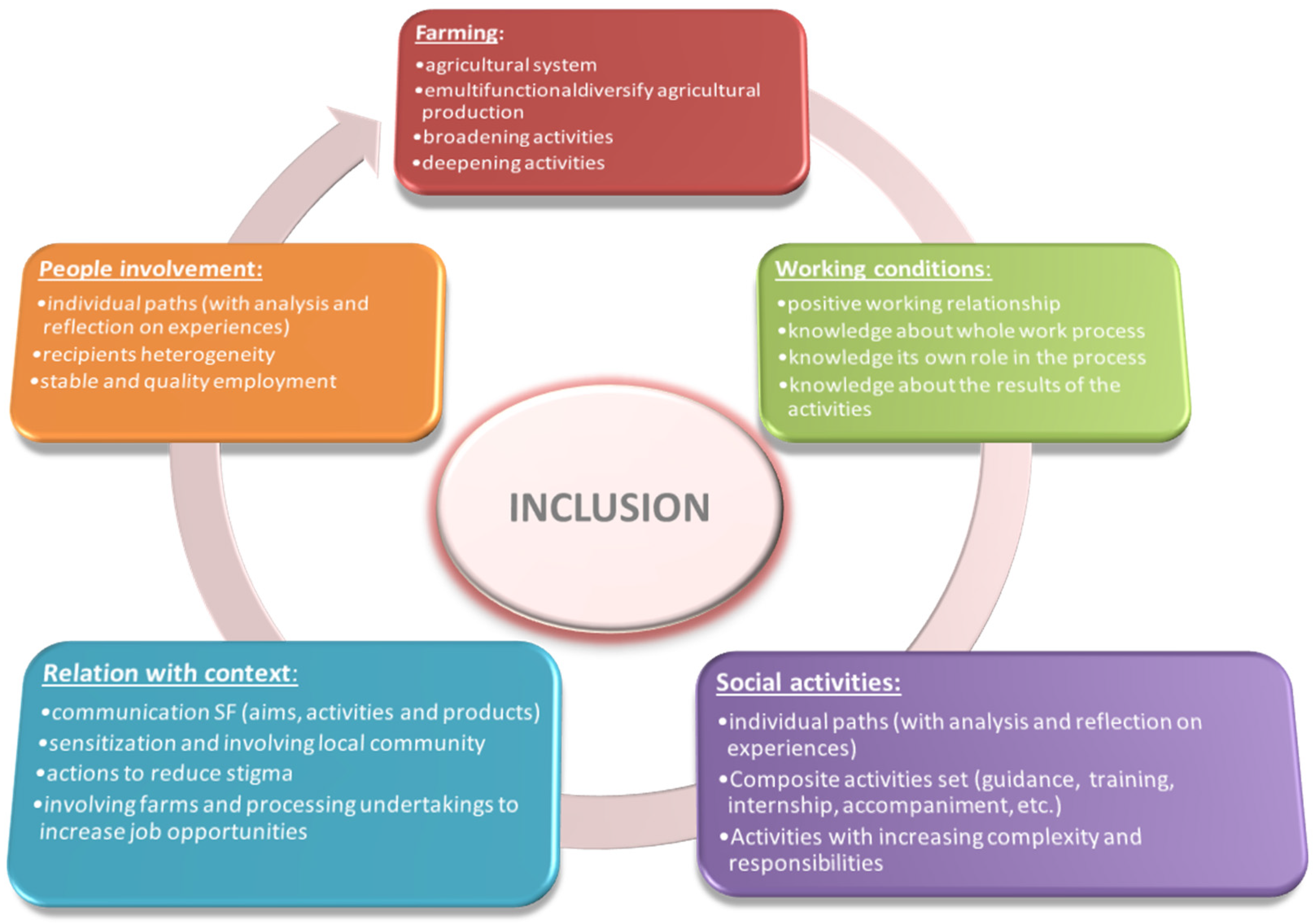

With specific regard to SF, taking into account the different spheres characterizing the concept, both empowerment interventions addressed to vulnerable people and actions for creating an inclusive context [

6] or environment [

33] can be considered. Previous analysis [

6] allows to identify some elements that contribute to creating it (

Figure 1) at internal (farm) and external (community and territory) level: (a) the farming characteristics, (b) the working conditions, (c) the social activities, (d) the relations with the external environment, and (e) the modality used for people involvement.

With regard to the farming characteristics in SF (a), several authors have agreed on the importance of a multifunctional approach [

34,

35] to the agricultural process and the presence of diversity in agricultural productions and broadening and deepening activities, including short-chain. Indeed, social farming is not a simulated situation of work, but an authentic working environment.

To achieve the purpose of social and working inclusion, therefore, it is indispensable to realize not only several social activities in an agricultural context or to provide jobs for vulnerable people, but mainly to design a complex system of action and relationship to connect the internal with external inclusion dimensions.

The working conditions (b) are very important to the empowerment dimension. They should be marked by a positive relationship between employer and employee and among workers, based on respect and trust, which favor the high self-esteem and create a positive learning environment for all employees. Another significant aspect is the presence of activities with increasing complexity and responsibilities, which allow people to increase their technical and professional competencies.

Knowledge about the whole work process, the role in the process for each worker, and knowledge about the results of the activities (commercialization, consumption, use of services, impact on local context) allow us to create links with the external environment.

These elements refer to the capabilities approach was formulated by Sen [

36,

37] and, afterwards, developed in normative, ethical, methodological, and political aspects. Among the most relevant aspects, in addition to cognitive and learning strategies, the capability approach contemplates the organization and planning of work.

The agricultural activities should be combined with social activities (c) realized by professional and/or social and health services with the aim to offer individual paths and the opportunity to reflect on their experiences. A complex set of activities to accompany people along the path needs to be designed, including guidance, training, internship, and accompaniment. The presence of activities with increasing complexity and responsibility can also contribute to addressing this objective.

The relation with the external environment (d) is a very important element to build an inclusive context; it concerns the intra and extra company relationships. Indeed, inclusion refers to a process that looks at the vulnerable people in its entirety integrated into a context, and it is addressed to the whole community.

The context takes importance since the internal capabilities acquired by a person can be expressed if the external conditions allow it. The more socio-cultural and economic conditions allow equity, the more vulnerable people can be included in real socio-economic processes. In this sense, it is essential to intervene also in the local community in which people live and work [

38].

We can, therefore, stress how there is an interdependence between individual freedom of agency and social, political, and economic opportunities available. Therefore, the well-being of the person consists not only in the activities that she/he is able to perform but also in her/his freedom or opportunity (ability) to use them [

36,

37]. Studies carried out in the Italian scholastic context [

39,

40] indicate possible environmental factors that can be taken into consideration to detect the students working in their personal, social, and environmental interactions, including socio-cultural barriers, such as those due to prejudices and stereotypes.

With regard to the last dimension considered by the model—modality used for people involvement (e)—the presence of heterogeneous users in the same set is a remarkable element contributing to the creation of quality SF [

6]. This approach avoids the ghettos of the people involved; it highlights differences by working on everyone’s abilities. Additionally, the SF actors carry out many initiatives with the involvement of the local community, to sensitize it and to reduce the stigma that characterizes some disadvantaged people, such as mental illness, being a foreigner, and, generally, the “otherness”. It is another important element that contributes to the construction of the inclusive context.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodological approach of this article is qualitative. To verify the meaningfulness and usefulness of the inclusive model of SF, four case studies [

41] of social and working inclusion addressed to immigrants are considered. The cases were selected using the purposeful sampling technique, that is, the selection of cases or samples that are likely to be informational rich with respect to the purposes of our study. The logic behind purposeful sampling is that a few cases studied in depth yield much information and many insights about a topic. The aim is to provide a description of the different detected issues that illuminate one’s understanding of the phenomenon [

42].

In 2019, under the Italian National Rural Network, a call to identify SF experiences was launched, addressed to the inclusion of immigrants, named “Rural Excellence” [

43]. Ten experiences have been chosen by a process of screening and evaluation involving experts named by the CREA and the Ministry of Agriculture. Four experiences have been chosen from this group to realize this analysis; the choice has been based on the following criteria: (a) innovativeness; (b) reconfiguration of existing social practices; (c) social engagement; (d) different geographical position (four different regions along the Italian peninsula).

The four cases are related to experiences promoted by the third sector and characterized by the involvement of farmers and other actors in the activities, with differences due to the specific contexts and purposes. A case study description is presented in paragarph 4.

The information was collected through detailed semi-structured interviews, field visits, documents, and reports analysis. Overall, 24 people were interviewed, each by 1 or 2 researchers (

Table 1), using a guide to collect information about the projects and their activities, people involved, factors that favor or hinder the inclusion, and outcomes.

The number of people interviewed is limited due to the non-availability of all the persons identified in the moment of field visit (Cambalanche and Diritti a Sud associations) and the achievement of the “theoretical saturation” [

44]. Indeed, the information collected with the people interviewed and the analysis of documents and observation activities was enough to complete the case studies.

The guide of the semi-structured interview consisted of the different typologies of questions, in part addressed to all persons interviewed and, in part, specifically addressed just some of them. Specifically, project partners (i.e., project managers, coordinators) were interviewed to collect information about the project and its outcomes and to analyze possible factors that favor or hinder the inclusion of migrants. Farmers were interviewed to understand the degree of involvement and the role in the project. The interviews with the recipients aimed to know their involvement in the initiative and the benefits they gained from it. Other actors were interviewed, when possible, to better describe the framework. All interviews were recorded.

The field visits have allowed us to gather more information on the experiences, such as availability and characteristics of the structures, cultivation methods, low or high use of facilities, and retrieve reports, disclosure documents, and other materials useful to complete the framework.

Content analyses [

45] were done manually and were focused on the meaning and semantic relationship of words and concepts, also regarding the inclusive approach described above. The set of categories used for coding have objective (e.g., typology of activity, people involved) and conceptual characteristics (related to the inclusive approach;

Figure 1).

The results are presented, taking into consideration all the dimensions and the items contained in

Figure 1.

Once coding was completed, the data collected were examined to compare the inclusive approach and draw conclusions in response to the research question.

4. Results

The inclusive approach, both from a social and work point of view, has been investigated and analyzed in four case studies. We have thoroughly analyzed the results obtained in terms of strengthening the ties with the territory and individual and collective growth, and the methods of inclusion and communication used.

The case studies analysed concern the experiences of the Manarola foundation (Liguria), the Cambalache association (Piemonte), the Diritti a Sud association (Puglia), and the Don Bosco 2000 association (Sicilia) (

Table 2).

4.1. Manarola Foundation

The Manarola foundation was founded in March 2014 in Liguria after around a year of numerous public meetings. The choice of the legal form, a foundation of participation, allowed them to establish the share capital with donations of money and land, made by more than 50% of the families of Manarola, an ancient village on the Ligurian Riviera located within the Cinque Terre National Park. Since 1997, the entire Cinque Terre area, a stretch of coast of about 10 km that appears as an amphitheater of terraces overlooking the sea, has been a World Heritage Site as a “cultural landscape” of extraordinary value, thanks to the network of terraces, created over the course of a millennium, which uniquely characterizes the landscape. The area in which the Foundation operates is made up of terraced fields, largely abandoned, which overlook the village; for this reason, the Foundation’s main objective is to rebuild the dry stone walls so as to restore and preserve the rural landscape and restart the local agricultural economy, restoring those fields to cultivation.

To remove one of the main obstacles to the cultivation of land, caused by the exodus of the local population over the past few years, the initiative Banca del Lavoro was promoted as part of the "Integr-Actions: Paths for social and work inclusion” project, supported by the Carispezia foundation, in collaboration with Caritas Diocesana, professional agricultural organizations (Confagricoltura and the CIA—Italian Confederation of Farmers) and the Cinque Terre National Park. The aim of the Banca del Lavoro is twofold: to find a workforce and create social–work integration paths for migrants and people in economic difficulties.

The scarcity of the local workforce because the younger generations prefer to invest in the tourism sector, has meant that the Foundation has had recourse to the Banca del Lavoro. The people available were young immigrants of La Spezia’s Caritas Diocesana coming from Mali, Senegal, and Nigeria, the first actors of a social agriculture laboratory articulated primarily in specific training courses, in the classroom and on the job, with equipment and materials made available by the Park. Provided free of charge by the project’s trade associations, the training aimed in the first phase to improve language skills and the knowledge on job security; in a second phase (on the job), practical lessons were added on green maintenance systems, on the arrangement of slopes and dry stone walls, and on the cultivation especially of vines.

As part of the “Banca del Lavoro” project, the Manarola foundation has launched a survey of the public and private land surrounding the village in order to rebuild the land properties by acquiring them for rent. Once reclaimed, the land is sublet by the Foundation to local farms and/or the Cinque Terre Agricultural Cooperative to be cultivated with vineyards. In this way, the risk of landslides and collapses is avoided, thanks to the action of roots of the vines and dry-stone walls to contain the soil, and one of the main local products (the Sciacchetrà wine) is supported. “Thanks to the Banca del Lavoro, in four years of activity, a little less than 8000 square meters of land were cleared and 418.50 square meters walls rebuilt. We set up a workshop on social agriculture that not only supported the integration of people involved but also favored their social inclusion”, said Giancarlo Celano, promoter of the Foundation.

The results obtained in Manarola with the social agriculture laboratories have, in fact, been multiplied: the integration between migrants and autochthone affected by the economic hardship involved and their social inclusion in the territory, the recruitment of 7 of them from some local farms, and the establishment of a social cooperative by 7/8 participants in the laboratory, almost all migrants. The cooperative offers maintenance services for walls and land to local businesses that request them through the CIA professional organization; the costs of the interventions are born by the Cinque Terre National Park that recognizes the local businesses in the role of custodians of the landscape and the territory.

The Foundation collaborates with various local associations and businesses to combat the abandonment of agricultural land and the strong landscape degradation that has caused severe environmental disasters over time (e.g., the flood in March 2011).

The activities of the “Integr-Actions” project will continue thanks to the “Stonewallsforlife (LIFE Climate Change Adaptation)”, a new project led by the Cinque Terre National Park and in partnership with the Foundation, together with the University of Genoa, ITRB GROUP, Legambiente, local authorities, and the Spanish and Greek associations.

4.2. Cambalache Association

The second case study is represented by Cambalache, an association of social promotion with agricultural value-added tax (VAT) registration born in Piedmont in 2011. The Association aims to promote a virtuous model of reception, assistance, and social inclusion for asylum seekers and international protection holders. It works in Alessandria (Piemonte). The Association is composed of a multidisciplinary team and offers different types of services: legal advice, psychological assistance, the teaching of the Italian language, communication, and promotion of activities. By assigning a central role to the training of assisted people, the Association promotes professionalization and requalification courses. To amplify the impact of its actions in terms of social inclusion, it also promotes voluntary courses, training activities for operators, and awareness-raising activities for citizens. Technical advice on beekeeping and agriculture is entrusted to external collaborators.

From 2012 to 2019, it managed extraordinary reception projects (Extraordinary Reception Centers (CASs)), while from 2016 to 2018, it managed a system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees (SPRAR) project in collaboration with local cooperatives and associations, which has guaranteed hospitality, support in all legal and administrative procedures, and linguistic, cultural and health assistance. Cambalache also has a design office and staff dedicated to the production and marketing of agricultural products.

Among the various reception projects activated, there is “Bee My Job”, an experimental social farming project conceived in 2015 to help refugees and asylum seekers to acquire new skills, to include themselves in a new social context, and to emancipate themselves economically. “The idea was to find an active production sector that was accessible to asylum-seekers and that required a medium–low qualification, that is, a job that could be learnt through intensive, one-and-a-half month-long professional courses. At that time, we identified beekeeping, an agricultural sector with a very long seasonality (from March to October), in which the beekeepers themselves reported difficulties in finding staff willing to train and then work on the farm”, declared Francesca Bongiorno, professional educator.

The number of young people who received professional training in beekeeping and in organic and synergic agriculture has increased gradually, from 15 in the first year (2015) to 25 in the following years, up to 75 in 2018 when the project was also started in the province of Bologna and in Lamezia Terme, with the help of the La Venenta cooperative and the Progetto Sud Community, respectively.

The participants, selected according to their technical and relational skills from the male holders of international protection and asylum seekers welcomed in the local context, followed an intensive theoretical–practical training course for two months for a total of 6 hours of lessons per day. The training also focused on language skills and job security; the course also provided guidance for the use of the services offered by the territory, active citizenship, and work inclusion. Once the training phase is over, the participants are admitted by carrying out an internship of at least 4 months at farms selected by the Cambalache association. Up to date, there are about 70 involved farms.

Also, in this case, the “Bee My Job” projects intend to include male asylum seekers and holders of international protection through the activation of an urban beehive within the Forte Acqui municipal park in Alessandria and organize meetings of beekeeping and environmental education address to young people and adults. The beehive and the synergistic urban garden created in 2019 in collaboration with Caritas Diocesana, as well as the store open at the headquarters of the association store, represent the privileged meeting places between the project beneficiaries and the local community. The products of the beehives and vegetable garden are sold at local and national public events, at the association’s sales point managed by two Italian civil service volunteers and two refugees, to local restaurants and to people of a solidarity group of purchase. All products are sold with the project label, in order to emphasize the importance of welcoming people in difficulty and cultural contamination.

The development of the project and the various awards and prizes obtained at national and international level (i.e., the “Welcome—Working for Refugees Integration” of the UNHCR–UN Refugee Agency) have contributed to making “Bee My Job” a model that can be replicated in different professional sectors and applicable to other types of vulnerable people. It was also extended in 2018 to women asylum seekers and unaccompanied foreign minors. In 2019, it was replicated in three other professional sectors, also involving people with disabilities, the unemployed over 50, and migrants at risk of labor exploitation.

The intense and uninterrupted networking with the various partners involved in the project was an element of strength that also favored the development of the communication phase, arousing the interest of national and international newspapers. The communication of the objectives, activities, and results achieved takes place through participation in local fairs and events, and educational meetings in bee and agriculture schools. Over time, a photographic exhibition has been created that portrays the new beekeepers and their teachers at work, and a short documentary is available on the Cambalache Association website.

4.3. Diritti a Sud Association

The Diritti a Sud Association was established in Nardò (Puglia) in 2014 with the aim to protect the fundamental rights of people in difficult conditions, primarily immigrant and foreign seasonal workers, affirming the culture of legality, the fight against mafias and organized crime, the abuse of power, and all forms of discrimination. Through the organization of cultural events, the Association promotes the culture of civil coexistence, the value of cultural, ethnic, and religious differences, active citizenship, inclusion, and social cohesion.

In 2014, the Association, together with the Solidaria association of Bari, participated in the realization of the social agriculture project “Sfruttazero”, which, through a mutualistic approach, aimed to support the tomato supply chain and its processing into a sauce, not using chemicals products and ensuring respect for workers’ rights. The project assumed particular symbolic value: Puglia, together with Emilia-Romagna, is one of the main production poles of Italian industrial tomatoes [

46] and it is also one of the Italian regions with the greatest number of areas with risk of serious labor exploitation of foreign workers in agriculture or with “indecent” situations [

8].

The Diritti a Sud Association carries out organic agriculture, which, by limiting the mechanical processing and, for example, providing the use of compost obtained from manure or by maceration of vegetable substances, reduces costs; at the same time increasing production by 50% even. The workers hired over the years are all made up of migrants and the unemployed over 50, or, in any case, people who have difficulty entering the world of work; these are seasonal workers whose contracts start, in some cases, from April, the month of sowing, and others from mid-July to the end of September, for the harvest. It is registered with the Chamber of Commerce as the farm allows the Association to take care of the entire supply chain, from sowing to harvest; the transformation is carried out at the structure of the Provincial Agricultural Consortium of Lecce, located 30 km from Nardò. Furthermore, the inclusion of social farming, among the statutory activities, allows the Association to regulate seasonal agricultural contracts based on land lease contracts, thus pursuing the aim of creating job opportunities, creating networks of relationships and collaborations with the territory, and recovering abandoned land. Workers are paid an hourly wage of EUR 7.40, plus pension contributions and insurance for accidents in the workplace.

The activity started with a production of around 2500 jars and continues, thanks to a crowdfunding campaign, which allows the two associations not only to purchase raw materials for the cultivation of tomatoes, but, above all, to share directly with consumers the idea of productive activity and the commitment to protect human dignity, the right to economic self-sustenance, and to determine oneself as an individual and part of a community. Over time, production processes and performance have improved, with a production of 16,800 bottles of tomato sauce in Nardò and about 8200 more in Bari. The associations, which take care of the whole production chain of sauce, have created “narrative labels” for the marketing of the bottles, which show the face of migrant workers and the over 50 and unemployed, to be active in the fight against forms of labor exploitation. Furthermore, 20% of the marketing takes place locally through participation in fairs and markets, through orders sent via the Association’s website or Facebook page or to small local shops that share the same ideals. However, 80% of the production is shipped to Solidarity Purchase Groups in Northern Italy, in particular, in the Veneto and Trentino-Alto Adige regions, or even abroad (France and Switzerland).

“The choice made did not betray us because the people who chose SfruttaZero over the years have increased and because, in recent years, a network of self-producers and distributors called FuoriMercato that acts on a national level from Piedmont to Sicily have united groups that, like us, self-produce trying to create a circuit of healthy economy and is respectful of the people and carry out practices of mutual aid and solidarity. This shows that it is also possible to create a different market”, declared Rosa Vaglio, the President of the Association.

4.4. Don Bosco 2000 Association

The Don Bosco 2000 non-profit association was established in 1998 in Sicily, with the aim of promoting men’s training and integration through the application of Don Bosco’s preventive educational system. However, it was from the years 2008–2010, that is, since the emergency of the management of immigrants on the island broke out, that the Association’s activities inevitably revolved around the reception, social integration, and all work inclusion of migrants who have landed mainly in the port of Catania.

The need to strengthen the regional reception systems led the Association to open, in time, five reception centers: the first was used in Catania in 2015 for unaccompanied foreign minors and was closed in December 2018; the rest are in the Province of Enna (Piazza Armerina, Aidone, Pietraperzia, Villarosa).

The areas of intervention of the Association are different and, in addition to the management of reception centers for immigrants, involved the implementation of education projects for global citizenship carried out with schools and local associations, and aggregation between young Africans and Sicilians. The Association carries out various projects, some of which aim to return the assets confiscated from the mafia to the community through the enhancement of human capital, and others to create places for social aggregation and “mutual reception”, in particular in the Lido and in the hotel in solidarity during the experimentation phase, which can also be frequented by people with physical disabilities, in which immigrants take care of the reception.

In addition to the literacy courses carried out in the very first reception centers, the Association promotes training courses at work as part of the SPRAR projects financed by the Municipalities through the National Fund for asylum policies and services, selecting companies from the provinces of Catania and Enna pertaining to the sectors of interest of immigrants for the matching phase. Since 60% of the reception immigrants declare that they are interested in working in the agricultural field, most of the job training projects aim to transfer their knowledge and skills necessary for effective, efficient, and sustainable management of vegetable gardens, also from an irrigation point of view. An initial course on workplace safety is followed by a period of coaching by the company tutor for learning efficient cultivation and irrigation techniques. The allowance paid to trainees, equal to approximately EUR 500.00, is co-financed at 50% by the farm; at the end of the training course, trainees are issued with a certificate of participation that acknowledges the activities carried out and the skills acquired.

The job placement takes place in compliance with the inclinations and aspirations expressed by the immigrants in reception and requires a preliminary mapping of local companies operating in different sectors, including agriculture. Through the work desk activated at the Aidone Center, the Association has managed to support the recruitment of several immigrants to welcome companies from other Italian regions; other migrants were hired, however, by the companies that had hosted their training internship within the SPRAR projects.

After attending specific training courses, some immigrants were hired by the Association as cultural mediators, also in the context of the international development cooperation projects carried out. “An emblematic case is represented by Ebrima Camara, who, over time, has become a true reference point for the other migrants welcomed in our centers and also for the local people who participate in the cultural, sports and recreational activities organized by us, enough to earn the title of “Don Bosco Nero”,” declared Agostino Sella, President of the Association.

Very interesting is the creation in 2017 of a social garden at the Don Bosco Colony in Catania; it is a local development project that has served as a testing ground for subsequent replication on an international scale. The garden is self-financed by the Association and cultivated by immigrants, both for self-consumption and on behalf of local families. The planning process was structured in such a way as to empower immigrants during all phases ranging from the preparation of the land and planting to the management of relations with the tenant families of the plots of land. So, work inclusion while restoring dignity to the efforts made by the immigrants, on the other hand, allows a more significant psychological result, allowing migrants to re-construct the idea of possible positive relationships with others. The actions of exchange and acquisition of knowledge, enhancement of skills, recovery, and enhancement of family memory and experiences gained before the migratory journey, enable the restoration of equal social dignity and economic and social emancipation. The positive repercussions of the social garden project are amplified, finally, in the international development cooperation projects aimed at achieving so-called “circular migration”. It is a migration model that can be counted among the best practices that can help face the migration phenomenon, simultaneously promoting the personal and professional growth of people inclined to migration and their economic success in the countries of origin. “One day, a Pakistani immigrant planted seeds of gombo received from the family and when the first plants came out, he told us that he felt “at home”. So, we decided to plant the peanuts too, which are eaten fresh in Africa. It was, therefore, an emotional question: through agriculture, we were also helping them to remember their origins and their family and to connect the present with their past”, said Agostino Sella, the President of the Association. The project activates virtuous cycles of training and skills acquisition in Italy and the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and innovation to the migrants’ African countries in order to create agricultural start-ups. In particular, in a first phase, the welcomed immigrants participate in a training course on the main techniques of agricultural production and irrigation management of a vegetable garden; in the following phase, they return to their countries of origin, where they actively participate in on-site awareness actions to recruit interested people, and once new study classes have been formed, they teach them notions of agriculture, horticulture, and self-entrepreneurship. Finally, the project includes support for agricultural start-ups made up of Africans. To date, thanks to the circular migration project, two agricultural start-ups have been launched: the first in Senegal, in the village of Tambacounda, and the second in Gambia, in Kekuta Kunda. The employment contracts stipulated allow immigrants to achieve two important results: maintaining humanitarian protection and, therefore, the freedom to return to Italy to continue participating in the international cooperation project, and above all, financially support their family of origin, sending part of their earnings through remittances.

The activity of the Association is enriched and supported by its membership of networks, such as the Salesian Federation for Social or International Volunteering for Development. In 2018, in order to allow the identification, also at an international level, of the actions carried out and of the products obtained with the commitment and full involvement of African immigrants in hospitality, a brand with a strong ethical connotation called “Beteyà” was created, which in Mandinka language means “beautiful and good”. The brand will be used in Sicily to identify a line of home and dress products, produced by a social enterprise set up as part of a project financed by the Con il Sud Foundation, in which seven immigrants work in hospitality. In Africa, the same brand is used for the marketing of horticultural products collected in the gardens created with Africans involved in the “circular migration” project.

5. Discussion

The following is a brief description of the case studies examined through five drivers that the model described in Chapter 2, to evaluate the pathways of social inclusion. In the

appendix, there are five tables for reading the relation between case studies and the criteria of the inclusive model.

5.1. Farming

The dimension of the inclusive model related to farming includes many aspects: the presence of a multifunctional approach to agriculture, a diversification of the production, and the presence of broadening activities, such as direct sales. All these characteristics are aimed at creating a context rich with opportunities for the involvement of a great number of recipients and workers (

Table A1).

The first driver to be taken into consideration when evaluating the pathways of social inclusion at work is the inclusive setting [

37], which is different in the experiences analyzed. The four experiences refer to training projects aimed at fostering the socio-work inclusion of migrants, and with this objective, they involve the agricultural world in a different way, but they have in common both the fact of involving farms for training and the recovery of land for agricultural use. In particular, Manarola Foundation (Liguria) recovers abandoned terraces and restored them. In the case of Cambalache Association (Piemonte), the beehives and the synergistic garden are built on municipal land. The Don Bosco 2000 Association (Sicilia) grows gardens on confiscated land from organized crime, and the Diritti a Sud Association (Puglia) grows tomatoes in unused plots of land, renting them by old farmers. Agricultural production activities concern horticulture and industrial horticulture (tomato), viticulture, beekeeping and, in line with the new definition of an agricultural farm [

47] that is not only a producer of primary goods but also of other connected activities, there is also the processing in wine, tomato sauce, and honey. For particular attention regards the labeling of the products for the recognition of the inclusion activity, the Manarola foundation has produced a label in collaboration with the social winery, with the narration of the project at the social winery; the Cambalache Association markets the products under the name of the project “Bee-My Job”; the tomato sauce of the Sfruttazero project shows on the label, in percentage terms, how much each step impacts on the price that the consumer pays (100% ethical and with 0% exploitation); Don Bosco 2000 uses a brand with a strong ethical connotation called “Beteyà”, which, in the Mandinka language, means “beautiful and good”. If we take into consideration the element of multifunctionality, the experiences analyzed highlight the different paths that manifest themselves in the involvement of immigrants at the farm’s point of sale (Cambalache) or in working alongside local farmers (Manarola—local farmers who are familiar with the ancient techniques of building walls and restoring terraces, Don Bosco 2000 at the Di Grazia farm, and the social garden at the Catania Center). The products are sold using the short-chain, i.e., solidal purchase groups (SPGs), local points of sale, ad hoc off-market circuits (Fuorimercato), and free of charge to the disadvantaged families.

5.2. Working Conditions

The working conditions concern the presence of a positive working relationship between workers and farmers but also the process of being able to consent to the knowledge about the whole work process and the role of any workers in the process itself. Another important aspect is the knowledge about the results of the activities, in terms of both production and consumption (

Table A2).

All experiences try to involve the territory in the project in order to foster a positive working environment. The horticultural activities of the Don Bosco 2000 Association take advantage of the relationships with the territory started through other activities managed by the Association; the Diritti a Sud association involves immigrants together with local workers and implements the paths of migrants with education activities for citizenship; the Ligurian experience is born by the will of the residents; the Cambalache project has provided a code of ethics and conduct for the companies that are involved in the project. The code of conduct is a declaration in which the farmers state that they are in compliance with all the rules for safety and hygiene at work; moreover, the companies must declare that they have no pending convictions for the exploitation of undeclared work and that they are committed to respecting the cultural differences of the trainees.

The experiences analyzed confirm the importance of sharing with migrants both knowledge about the whole work process and its own role in the process; knowledge about the results of the activities in terms of commercialization, consumption, use of services, and impact on the local context.

In these terms, the choice of production processes that require a medium–low qualification through professionalizing intensive courses that allow them to enter the labor market is a pathway common to all experiences.

5.3. Social Activities

The presence of intentional and conscious social activity is the third dimensions of the inclusive model and regards once again the presence of individual paths (with analysis and reflection on experiences), but also the offer of a composite activities set, including guidance, training, internship, and accompaniment, in order to support the socio-working inclusive process. Activities with increasing complexity and responsibilities are included in this dimension because they favor professional growth (

Table A3).

The individual paths are built based on the assessment of the life experiences lived by immigrants, sometimes extremely difficult. Often, in fact, they escaped from conflicts, from the obligation of permanent military service, from local armed groups or situations of deep poverty. The projects of social and labor inclusion carried out by the cases examined are, therefore, built primarily on the principles of equal human, social, and working dignity of immigrants and aim at the enhancement of the knowledge, skills, and aspirations of immigrants. With different procedures, all the cases examined show attention to the prior assessment of the skills and aspirations of immigrants by individual educators, trainers and tutors, or staff established ad hoc.

The four experiences examined have different interpretations of involvement due also to the position of their activities within the entire path that each participant has undertaken with the social-health services. Since they are associations or foundations addressed aims different from those of cooperatives (type A or B) or farms, they have a limited role with respect to individual paths construction. However, the Don Bosco 2000 Association offers support and guidance to regularize immigration employment statuses, housing intermediation, and support to conclude their education. The project addressed to immigrants is funded by the system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees (SPRAR) and other national and international funds aimed at inclusion, realized in cooperation with other local actors. The Don Bosco 2000 role consists of supporting individuals in their inclusion paths, including reflections about the path itself.

With regards to the presence of a composite activities set, the Don Bosco 2000 Association and the Manarola Foundation propose formal activities of training and mentorship in order to learn the profession. However, the other two experiences also adopted an educational approach as part of their interventions, which is expressed in informal training on the job. Sfruttazero, in addition, offers accompaniment services for other life spheres (e.g., housing problem, the regularity of the documents).

In the four experiences, the workers are involved in activities with increasing complexity and responsibilities with the aim of developing competences and marketable skills. Highly interesting is Don Bosco 2000: the proposed path also offers learners the opportunity to gain expertise to improve their livelihood areas, such as small-scale agriculture and micro-enterprise training. In short, they propose to immigrants to develop themselves from agricultural workers to trainers and entrepreneurs, in a logic of circular migration.

5.4. Relation with Context

The relation with the context is a crucial and critical element because it makes the difference in respect of other approaches to inclusion that are focused just on people to be included. This dimension concerns the presence of communication about aims, activities, and products of social farming and the involvement of farms and processing undertakings to increase job opportunities. Another important element is the presence of actions to reduce stigma and sensitize the local community, which is the second term of the inclusion process (

Table A4).

The nature and quality of the relationships that the experiences examined have started and consolidated in the territorial area and at national and/or international levels, representing central elements for the immigrants’ social and work integration development. The external dimension of the inclusive process can, in fact, play a fundamental role for the stability and qualitative strengthening of AS activities, even contributing to redesigning the social role of local realities and identifying farms, associations, and social cooperatives as promoters, guarantors, and catalysts of virtuous processes of the social and work inclusion of weak subjects. The analysis focused on the social and working inclusion activities of four case studies to verify the presence and role of local community awareness and involvement actions aimed at reducing stigma. The analysis also focused on farms scouting activities and the creation of relationships between immigrants and farmers in order to increase job opportunities. The communication of social inclusion actions carried out, or also exclusively through agricultural and agri-food activities, has been supported by the intense network work carried out with the different project partners. The communication takes place first of all with internet sites in which there are specific sections dedicated to socio-working inclusion projects, collections of papers, and press release and informative videos aimed at recounting projects experiences (in the case of the Cambalache and Don Bosco 2000 Associations), and to fundraising (for the Manarola Foundation). In addition, printed materials are added, such as explanatory brochures, informative reports, and, for the Don Bosco 2000 Association, also periodical magazines, for reporting the projects and the results in terms of social inclusion and economic and cultural development. The objectives, activities, and results achieved are also communicated at fairs, local events, and educational meetings, such as those organized by the Cambalache Association on beekeeping and organic farming or through the realization of photographic exhibitions that portray the work of new beekeepers and their teachers. All the projects collaborate with one or more networks of local, national, and, in some cases, also foreign, public, and private entities. The Diritti a Sud Association uses a network of actors also composed of the Solidaria Association, the Fuori dal ghetto collective, and the Osservatorio migranti Basilicata, while the network of auto producers and distributors, called FuoriMercato, operates nationally. The Don Bosco 2000 Association participates in national organizations, such as the Salesiani per il Sociale Federation, and the International Volunteer Service for Development Federation collaborates with various local public and private entities (i.e., police headquarters, schools, production companies also in the agricultural sector) and, carrying out development cooperation projects in Senegal and Gambia, has also started collaborations with African public and private entities. Participation in various collaboration networks often facilitates the implementation of the projects promoted, making the activity carried out by the experiences examined very dynamic, and also contributes to amplifying the ethical and social profile of their commitment, allowing the integration of production activities and, in the case of the Manarola Foundation, of recovery and conservation of the landscape with those of socio-occupational integration.

Thanks to global citizenship education projects with schools, cultural and sporting events, social gathering centers, and training placements at local companies, the awareness of communities towards migration and reception issues have increased. The creation of support networks for immigrants for the protection of their rights has played a fundamental role in the action to contrast the stigma, allowing the creation of solidarity and mutual respect with immigrants. The Manarola Foundation, through the website, becomes associated with other people who can donate the desired amount, and also with the purchase of individual stones to be given away on holidays, on which the names of the donors are engraved. The Cambalache Association also promotes voluntary courses and training activities for operators, as well as on bee educational and environmental education meetings for young people and adults. The Diritti a Sud Association has adopted “narrative labels” as described in

Section 4.3, an interesting example. The launch of widespread reception systems, for example, in Aidone and Villarosa by Don Bosco 2000, has revitalized the countries from a social and economic point of view, putting abandoned houses back into use and facilitating the full and effective social inclusion of immigrants in the local context. This result was also achieved with the cultivation of the social garden at the Catania Center, where integration also passed through culinary–cultural exchanges and exchanges of knowledge on African horticultural products cultivated in the garden and shared with Sicilian youth. Other awareness-raising and fundraising actions, through the "Diamo loro retta" campaign, were carried out to enable the completion of some immigrants’ studies.

All the case studies examined have in common the collaboration with local farms interested in supporting their ethical and social commitment. In Manarola, the need to create long-term social-working inclusion paths for migrants and unemployed was born together with those for safeguarding the territory and restoring the production of abandoned and degraded terraces. To achieve these objectives, “Banca del Lavoro” and the organization of training and job placement courses were used. The project gave to the 7 participants, most of them immigrants that took advantage of the training, the opportunity to make a social cooperative; the cooperative provides free (costs incurred by Banca del Lavoro) maintenance services for walls and land to local businesses that request them. Cambalache today has a collaboration of about 70 local companies, where training courses of at least 4 months on beekeeping, organic cultivation, and pruning techniques are carried out. In the case of the Diritti a Sud and of the Don Bosco 2000 Associations, the agricultural and processing companies are selected for the matching phase, which provides for the start of training internships with classroom and field lessons, generally lasting 5 months.

5.5. People Involvement

In social farming paths, an important driver to promote social and working inclusion is the ways and means of involvement of participants, that is, the fifth dimension of the inclusive model. People are identified and involved in the projects and activities in collaboration with the social and health services at a local level. It is possible because the Italian experience is based on a close collaboration between public and private bodies to realize the SF activities. Many partnerships are created in response to public calls (i.e., the European Social Fund or Rural Development Programmes); other informal or formal networks are addressed to realize SF in implementation of national or regional laws on educations, health, and work inclusion. They can also be oriented to promote individualized plans for the inclusion of vulnerable people, realized in collaboration with enterprises.

With specific regard to migrant interventions, the SPRAR and CAR systems provide for training and internship activity in order to favor the process of inclusion and the improvement of the competences and their official recognition.

Therefore, people involvement relates first to the presence and kind of individual paths, which should also provide the activities of analysis and reflection on experiences with the support of professionals (e.g., psychologists, psychiatrists, educators). The model also considers the heterogeneity of recipients as an element for the intervention quality. Another important aspect is the stability and quality of employment in order to achieve and improve the right labor market, especially for vulnerable people (

Table A5).

The individual paths have been presented above (social activities).

The Cambalache Association realizes its activities in collaboration with local actors under the SPRAR and CASs. The participants are identified based on their technical and relational competences by a staff composed of psychologists, pedagogists, and social workers. The motivation analysis is also an important step in selecting participants. The Manarola Foundation, instead, is a part of a complex partnership that promotes the project, but it contributes just marginally at participants’ skill assessments, opportunities analysis, and reflection on experience. The role of trainers and tutors is limited at educational and job spheres, while the complete take-up of cases takes place at a local social service level. The experience of the Diritti a Sud Association, finally, is born under a volunteer context without connections with local social services. Possible paths depend on the participant—the Diritti a Sud Association member relationships are not encrypted into a specific protocol for intervention.

With regard to the participation of different recipients, almost all case studies involved both Italian and immigrant workers. However, all the experiences are involved in activities aimed to inform and raise awareness among citizens and farmers. The professional traineeship is the main form of contract used in examined cases, mainly in the first phase of the projects; it is present in all the projects excluding Sfruttazero. In reality, the traineeship is a trainer instrument and not a work one, but in Italy, it represents the main tool to access to stable and quality employment, especially for immigrants. Sfruttazero uses seasonal contracts to involve participants in the tomatoes production, which is an agricultural production particularly subject to illegal employment and the caporalato phenomenon. The Association also runs an info-point on workers’ rights to support immigrants and local workers.

6. Conclusions

The problem of the migratory phenomenon managing takes on different forms and levels of emergency in the various Italian regions, whose attractiveness for immigrants also varies according to the labor needs of the local production systems. Social farming can be a concrete response to the exploitation of migrants’ work by promoting paths of social inclusion, developing innovative forms of hospitality, exploiting a solid and effective collaboration between farms, social cooperatives, associations, local services, and schools. In this respect, the internship period allows participants to acquire agronomic and management skills, to get to know more complex farm in terms of the intensity of mechanization than those of their background. The internship is an instrument of the active labor market and a monthly salary for about 6 months expected for recipients. It is generally used in order to offer opportunities to improve own competences but also to have an income.

The case study analysis shows that to counter the tendency to stigmatize the immigrants—unfortunately still current—actions capable of reducing social prejudice must be promoted, for example, by using positive images and appropriate language, fighting discrimination in the workplace, promoting the opening and functioning of gathering places and, more generally, by supporting active reception and social–work integration policies. It is important to work on raising public awareness, in order to facilitate awareness of prejudice, the first step in overcoming discrimination. The organization of social farming in networks involving a heterogeneous group of actors is one of the most effective tools to encourage the integration of migrants and contrast the tendency to stigmatize them [

48]. The study focuses on the whole approach of SF experiences examined, without a specific analysis of effects on the participants; however, the information collected seems to demonstrate satisfaction of the recipients in participating in the training and labor activities carried out, as well as gratitude for the ways in which they are respected in their skills and aspirations. Interviews with the beneficiaries have revealed that the main effects obtained are those on individual levels, such as the recovery of dignity, confidence in one’s own abilities, and in the building of healthy and equal relationships with people, respect for their aspirations for study, work, and a future free from violence. Also, with regards to the paths and involvement modality, they claim to feel accepted and valued. To better understand results and benefits for the participants, anyhow, it could be useful to realize specific research with the collaboration of experts of different disciplines.

Historically welcomed as a "multifunctional" workforce, especially in rural areas, the presence of immigrants responds to different working needs (i.e., agriculture, tourism, construction) [

49]. Despite the limitations of the methodology, the analysis of some case studies helps us to better understand how migrants are included in social farming activities and which are the possible paths. Migrants, in the cases examined, found opportunities for inclusion in the agricultural sector, often catching up on their experiences and knowledge before embarking on the migratory journey, with important repercussions in the local social system, sometimes in need of a specific workforce. The period of internship at the farms is useful to the participants to acquire agronomic and managerial skills, to know the more complex farms in terms of intensity of mechanization than those of their background. The experiences of AS, therefore, are supporting the socio-cultural insertion processes, also triggering stabilization dynamics accepted by the territories, modifying in some cases the mentality of local communities that are not always favorable and open to the reception of migrants from the beginning, and changing in some cases the mentality of the local communities, which have not always shown themselves to be favorable and open to the reception of migrants from the outset. Among other things, as shown, for example, by the experience of the social gardens initiated by the Don Bosco Association, social integration is often also facilitated by cultural–culinary exchanges, such as those that took place following the cultivation of common vegetables in Africa, like the elbow or peanut, usually eaten fresh. Integration is to be understood as a bilateral process, which, when fully realized, involves both the personal level, affecting personal convictions and attitudes, as well as collective, sometimes leading to radical changes in the propensity to welcome. Some local communities that were, in fact, initially very closed regarding projects for the reception of immigrants and their integration, have changed their opinions and appreciated their presence, seeing them as a source of culture, improvement of social and cultural activities, and liveability of the municipality, as well as growth and economic development.

The fight against the caporalato is more effective if accompanied and supported by inclusive actions that aim to reduce social prejudice and affect food-conscious consumption and cultural substrate. Social disapproval for the immigrant, as well as for the “other” in general, is not always the result of a conscious act. For this reason, all associations and foundations engage in migrant integration actions, constantly promoting public awareness actions in order to help overcome diversity, promoting cultural contamination, and positive relationships between immigrants and local communities.

The study provides numerous suggestions to reflect on the Italian inclusive model, as it provides useful elements for the implementation of the Guidelines in social farming that are being implemented, as provided by Law 141/2015. We refer to the importance of training of operators to lead/work in a real productive reality (farm), to the need for efficient scouting of companies to ensure the best meeting between farms and operators. Moreover, the possibility of an inclusive insertion in the context is central.