Can Companies Survive a Multi-Brand Crisis? Research on Consumer Scapegoating

Abstract

“And Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins. And he shall put them on the head of the goat and send it away into the wilderness by the hand of a man who is in readiness. The goat shall bear all their iniquities on itself to a remote area, and he shall let the goat go free in the wilderness.”——Leviticus 16: 21–22

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Multi-Brand Crisis and Brand Trust

2.2. Scapegoating Effect

2.3. Mechanism of Consumer Scapegoating Effect: Cognitive Dissonance

3. Methodology and Results

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Pre-Test 1

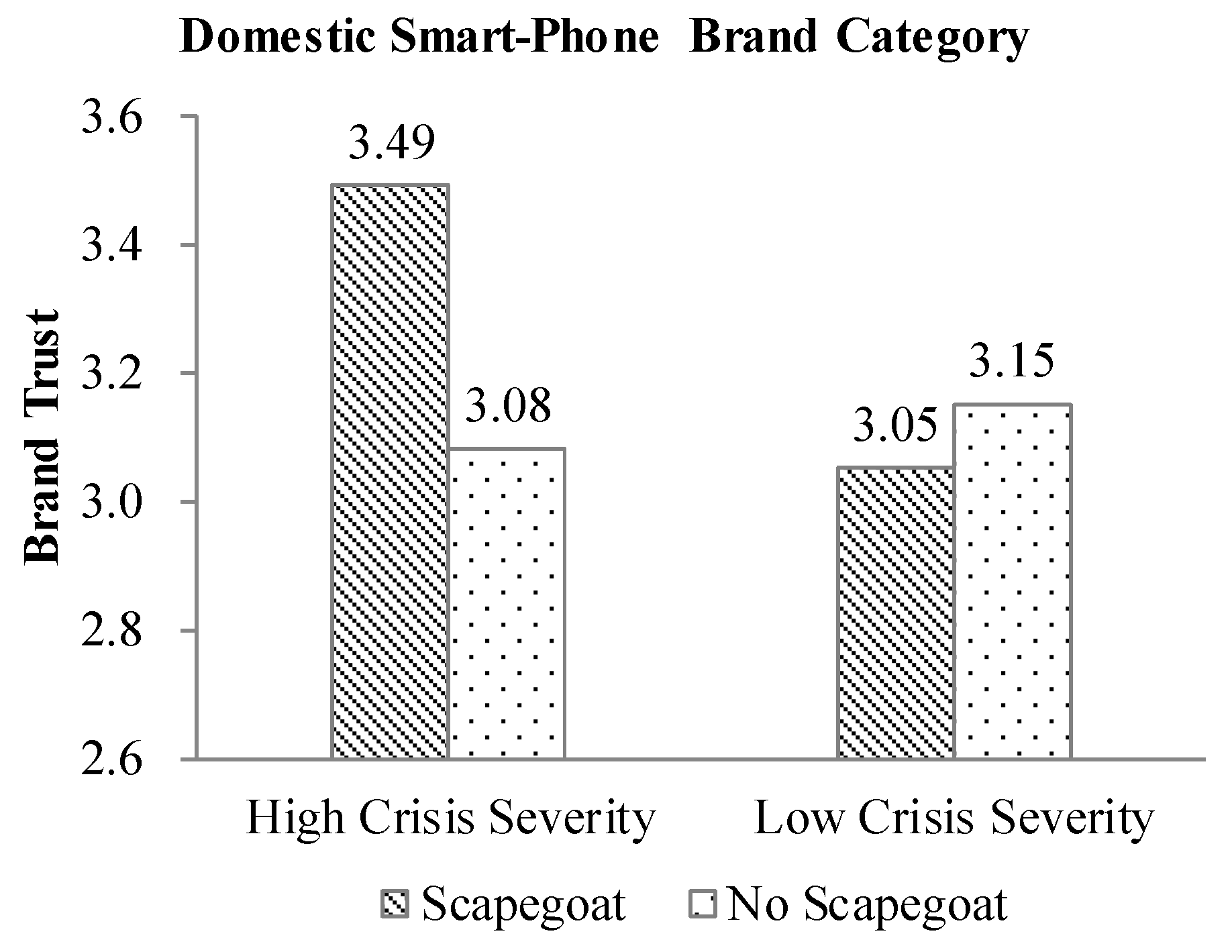

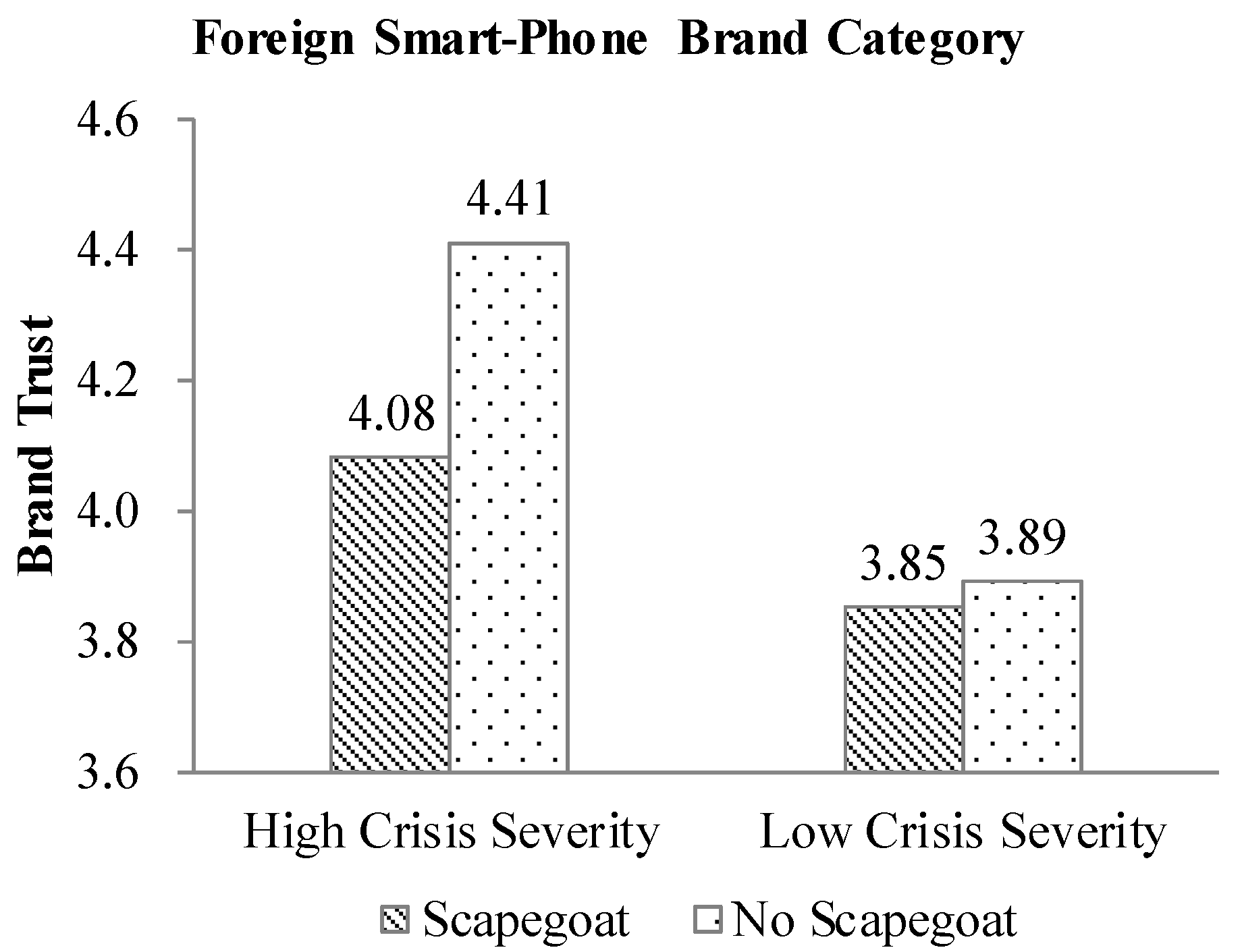

3.1.2. Main Study

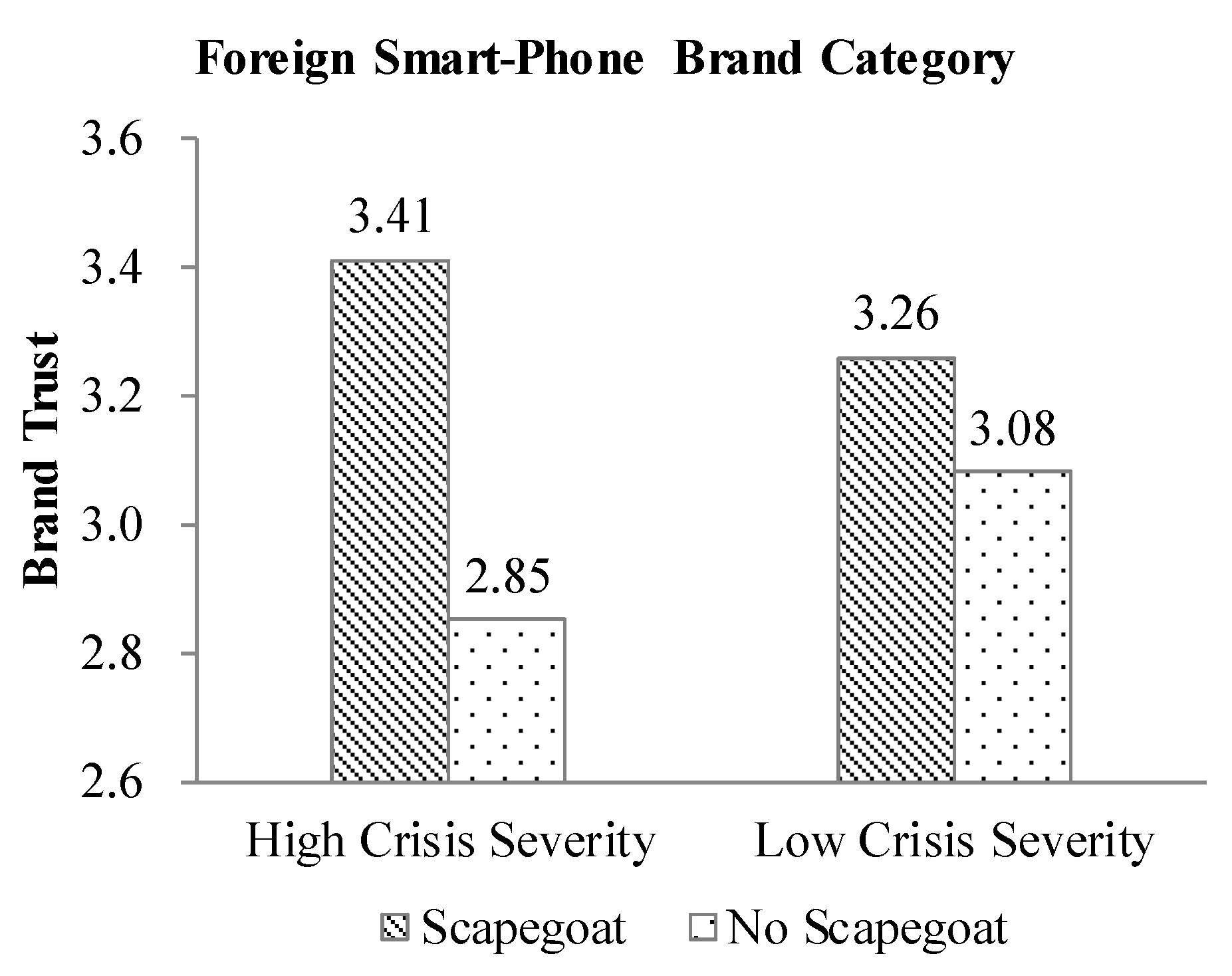

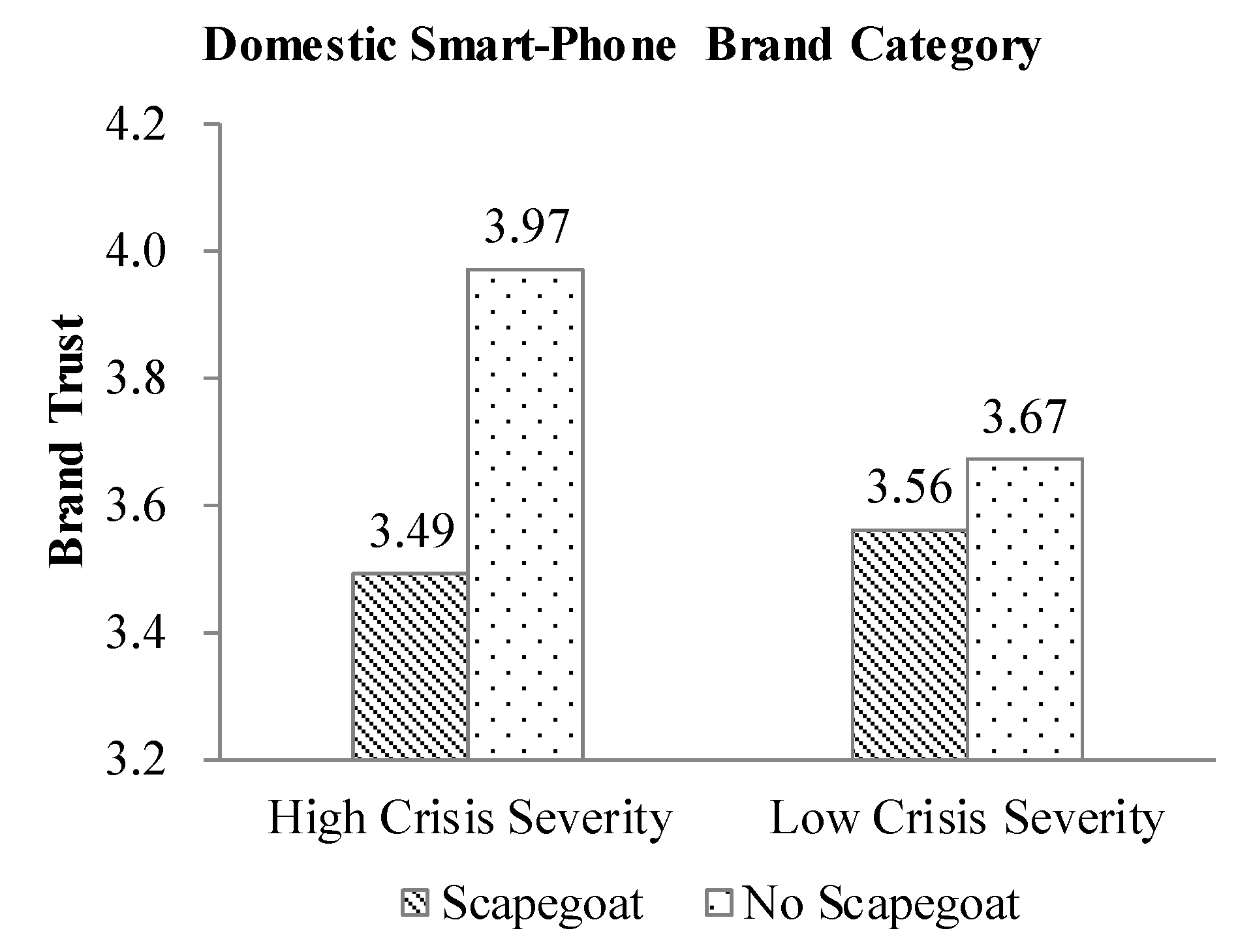

3.2. Study 2

4. Conclusions and Implications

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Theoretical Contributions

4.3. Managerial Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Custance, P.; Walley, K.; Jiang, D. Crisis brand management in emerging markets: Insight from the Chinese infant milk powder scandal. Mark. Intell. Plann. 2012, 30, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Knight, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Mather, D.; Tan, L.P. Consumer scapegoating during a systemic product-harm crisis. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 1270–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Knight, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Mather, D. Guilt by association: Heuristic risks for foreign brands during a product-harm crisis in China. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Knight, J.G. Spillover of distrust from domestic to imported brands in a crisis-sensitized market. J. Int. Mark. 2015, 23, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Guo, X.; Guo, J.; Wu, J. China’s dairy crisis: Impacts, causes and policy implications for a sustainable dairy industry. Int. J. Sus. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi-Tehrani, A.K.; Pontell, H.N. Corporate crime and state legitimacy: The 2008 Chinese melamine milk scandal. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2015, 63, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; McMurray, A.; Xue, J.; Liu, Z.; Sy, M. Industry-wide corporate fraud: The truth behind the Volkswagen scandal. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3167–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, L.F.; Rocha, T.V.; Da Fonseca, M.R. Corporate communication actions in response to crises: Empirical evidence in food fraud in Brazil. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2019, 10, 458–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, D.C. Evaluating ethical approaches to crisis leadership: Insights from unintentional harm research. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011, 98, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ganesan, S.; Liu, Y. Does a firm’s product-recall strategy affect its financial value? An examination of strategic alternatives during product-harm crises. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, L.; Hawkins, J.; Kitchen, P.J.; Rose, L.C. Brand sickness and health following major product withdrawals. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyser, S.A. Corporate brand reputation and brand crisis management. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 590–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, D.; Silvera, D.H.; Meyer, T. Exploring differences between older and younger consumers in attributions of blame for product harm crises. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2005, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Silvera, D.H.; Meyer, T.; Laufer, D. Age-related reactions to a product harm crisis. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Analysis of management strategies of corporate public relation crisis. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Laufer, D.; Wang, Y. Guilty by association: The risk of crisis contagion. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeren, K.; Dekimpe, M.G.; Helsen, K. Weathering product-harm crises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Pillutla, M.M. Impact of product-harm crises on brand equity: The moderating role of consumer expectations. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Crisafulli, B.; Quamina, L.T.; Kottasz, R. The role of brand equity and crisis type on corporate brand alliances in crises. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Dawar, N.; Lemmink, J. Negative spillover in brand portfolios: Exploring the antecedents of asymmetric effects. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehm, M.L.; Tybout, A.M. When will a brand scandal spill over, and how should competitors respond? J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Helsen, K. Consumer learning in a turbulent market environment: Modeling consumer choice dynamics after a product-harm crisis. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Jing, F.J.; Tu, M. Study on the industrial spillover effect of single-brand or multi-brand product-harm crisis. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2012, 11, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, N.; Bless, H. Assimilation and contrast effects in attitude measurement: An inclusion/exclusion model. Adv. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Häfner, M. How dissimilar others may still resemble the self: Assimilation and contrast after social comparison. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiler, T. Comparison processes in social judgment: Mechanisms and consequences. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, R. Scapegoat (Y. Freccero Trans.); Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer, M. Do normative transgressions affect punitive judgments? An empirical test of the psychoanalytic scapegoat hypothesis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1650–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. The ego and the ID (J. Riviere Trans.). In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud; Strachey, J., Ed.; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1990; Volume 19, pp. 3–66. [Google Scholar]

- Savun, B.; Gineste, C. From protection to persecution: Threat environment and refugee scapegoating. J. Peace Res. 2019, 56, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomulya, D.; Jin, K.; Lee, P.M.; Pollock, T.G. Crossed wires: Endorsement signals and the effects of IPO firm delistings on venture capitalists’ reputations. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 641–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, P.; Benson, M.L. The evolution of corporate accounts of scandals from exposure to investigation. Br. J. Criminol. 2020, azaa001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.; Lei, J. Brand crises: The roles of brand familiarity and crisis relevance in determining the impact on brand evaluations. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.G. Social Psychology, 10th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Tavris, C.; Aronson, E. Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts; Harcourt: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Tormala, Z.L.; Briñol, P.; Jarvis, W.B.G. Implicit ambivalence from attitude change: An exploration of the PAST model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydell, R.J.; McConnell, A.R.; Mackle, D.M. Consequences of discrepant explicit and implicit attitudes: Cognitive dissonance and increased information processing. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lee, S.Y.; Stevenson, H.W. Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales among East Asian and North American students. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 6, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Jones, P.S.; Mineyama, Y. Cultural differences in responses to a Likert scale. Res. Nurs. Health 2002, 25, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stening, B.W.; Everett, J.E. Response styles in a cross-cultural managerial study. J. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 122, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form; The University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Brand Category | Sample Group | B 1 | 95% LLCI 2 | 95% ULCI 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis Brand Category | Entire Sample | 0.2097 | 0.0297 | 0.4679 |

| High Crisis Severity | 0.3141 | 0.1503 | 0.5560 | |

| Low Crisis Severity | 0.1044 | −0.0181 | 0.2611 | |

| Competing Brand Category | Entire Sample | −0.2089 | −0.4275 | −0.0319 |

| High Crisis Severity | −0.3129 | −0.5320 | −0.1660 | |

| Low Crisis Severity | −0.1040 | −0.2594 | 0.0127 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Lei, J.; Gao, H. Can Companies Survive a Multi-Brand Crisis? Research on Consumer Scapegoating. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103990

Zhang X, Zhang H, Lei J, Gao H. Can Companies Survive a Multi-Brand Crisis? Research on Consumer Scapegoating. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):3990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103990

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xuan, Hongxia Zhang, Jill Lei, and Hongzhi Gao. 2020. "Can Companies Survive a Multi-Brand Crisis? Research on Consumer Scapegoating" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 3990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103990

APA StyleZhang, X., Zhang, H., Lei, J., & Gao, H. (2020). Can Companies Survive a Multi-Brand Crisis? Research on Consumer Scapegoating. Sustainability, 12(10), 3990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103990