Systematic Review of Sustainable-Development-Goal Deployment in Business Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction, Background and Literature Review

2. Methods

2.1. Research Questions

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

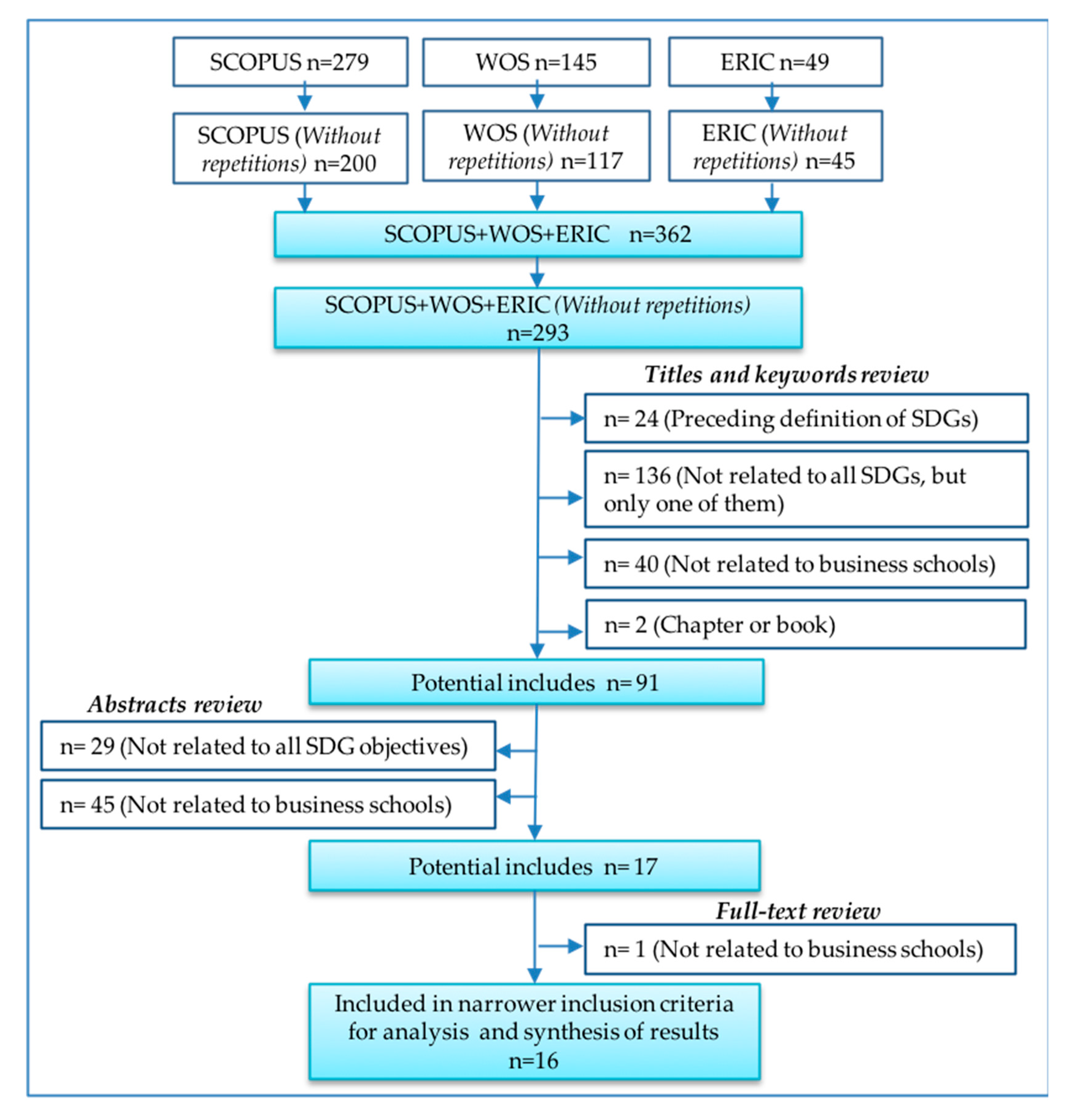

2.4. Trial Flow/Selection Process

2.5. Quality Assessment (of Initially Considered Studies)

3. Results

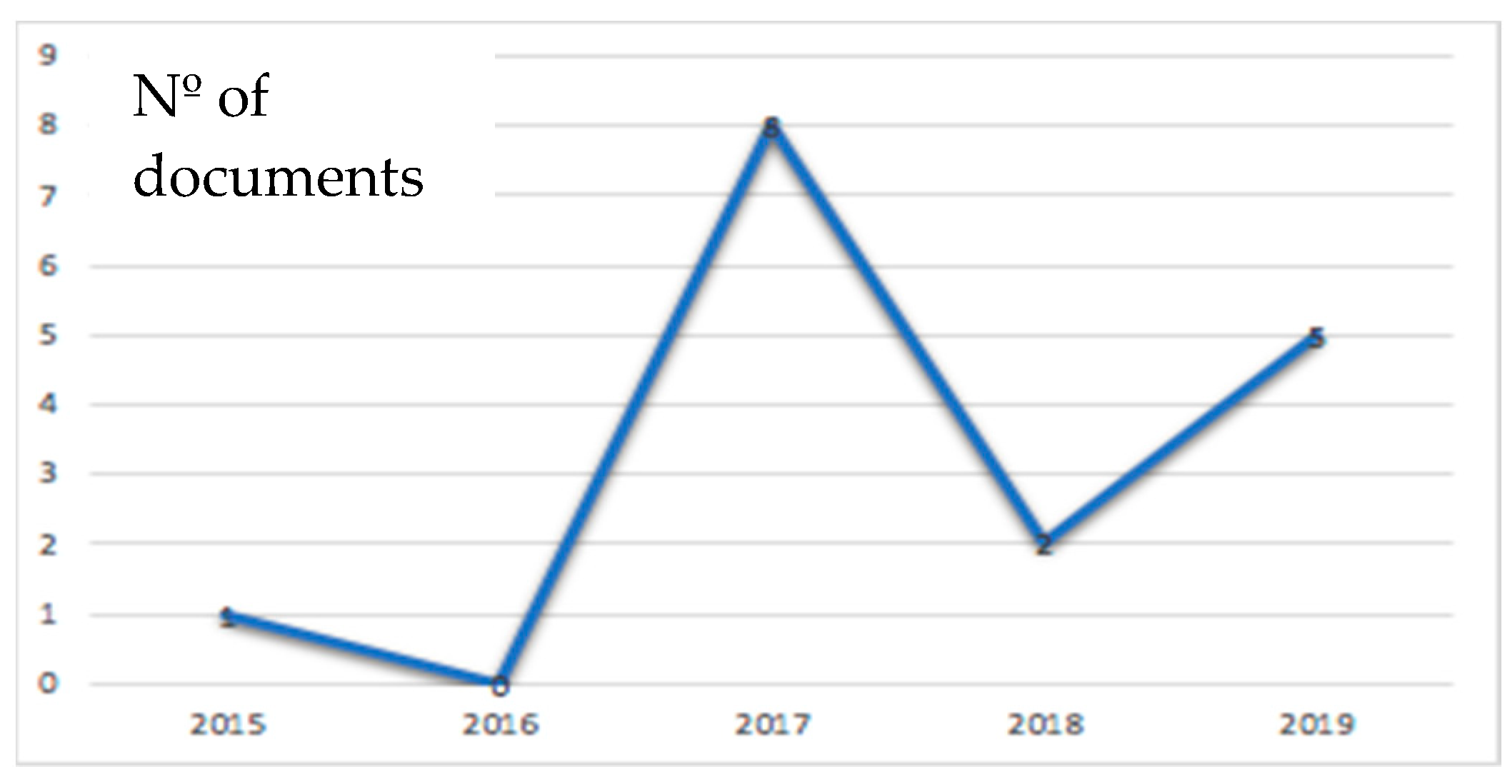

3.1. Study Descriptors

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Study Content: Type of Intervention and Conclusions

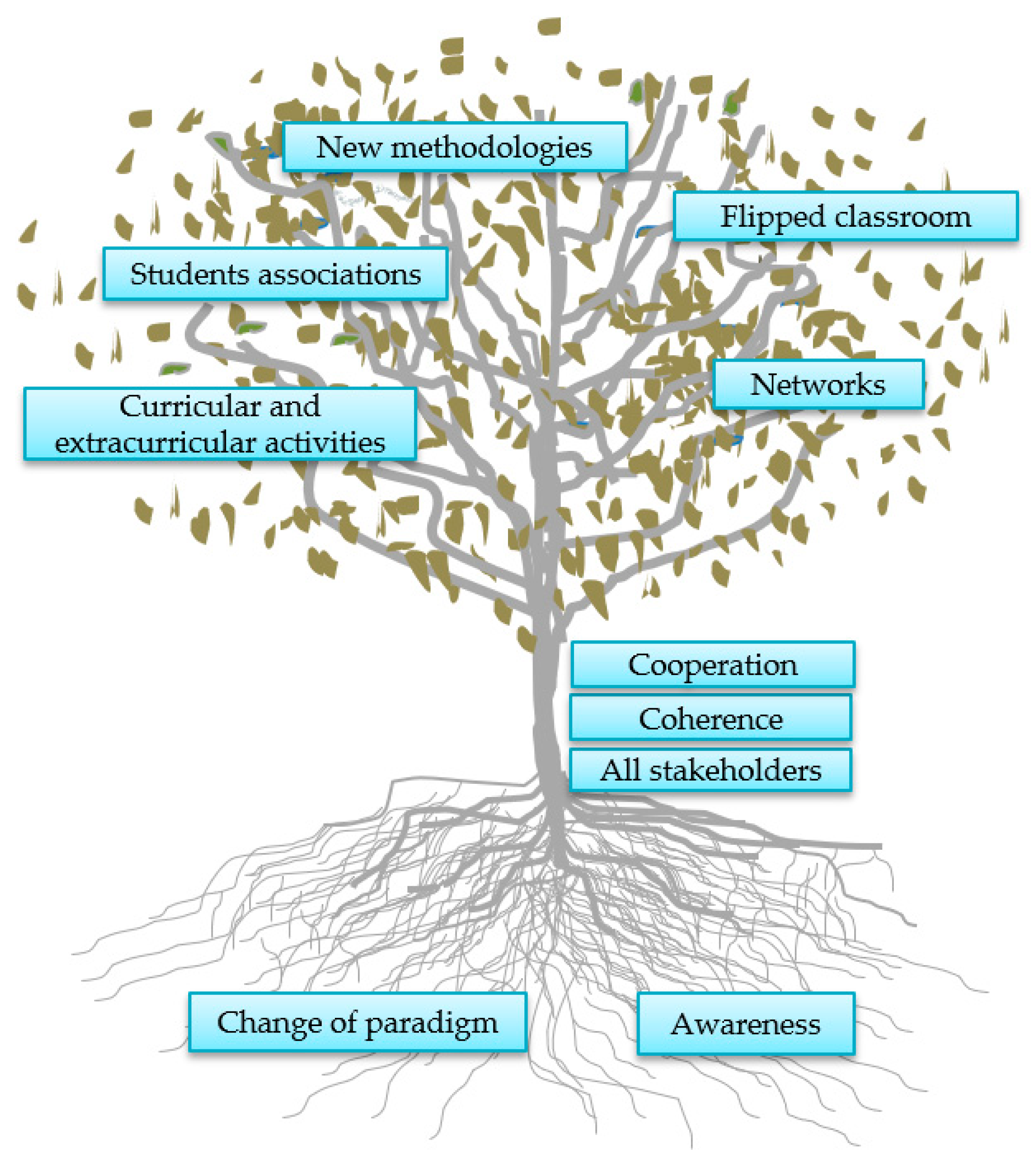

4. Discussion

- More research should be done to better understand the organizational context (political and cultural) for implementation of ESD in higher education [45].

- Greater attention should be paid to the challenges and opportunities posed by the increasingly internationally diverse profile of both student and staff, and to related topics such as globalization, diversity, or culture [45].

- More debate is needed regarding how responsibility shared in the higher education context is [45].

- More work should be done to explore how to engage students directly with civil society, non-profits or public policy in the key areas impacted by the SDGs [55].

5. Conclusions

- Research on any particular SDG in a BS has not been reviewed, considering that it was more interesting to first know the state of the art from a more general perspective;

- For a similar reason, searches in marketing or finance education were discarded;

- The choice to restrict our search to English and Spanish-written articles may have influenced our findings, not considering other relevant results;

- The selection of only three specific databases;

- Documents after July 2019 have not been reviewed, nor books or book chapters;

- The reviewed studies were carried out in different contexts, so cultural variables may have had an influence that we have not considered, and interpretation of the studies was hindered by the fact that many of the studies provided limited information on their context;

- The concept we explored (interventions to deploy SDGs in BSs) is broad and presents limitations in providing a consistent definition within the interventions; and

- The variability of the interventions and the small number of studies with primary data collection made it difficult to reach a conclusion on the effectiveness of the interventions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D.; Papaoikonomou, E. A Multi-level Perspective for the Integration of Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability (ECSRS) in Management Education. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piza, V.; Aparicio, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Marín, R.; Beltrán, J.; Bedolla, R. Sustainability in Higher Education: A Didactic Strategy for Environmental Mainstreaming. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO World Conference on Education for Sustainable Development: Bonn Declaration; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: http://www.esd-world-conference-2009.org/fileadmin/download/ESD2009_BonnDeclaration080409.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2019).

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development: Exploring the Student Teachers’ Views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, C.B.; Whelan, R.; Stoffer, H.; Todd, E.; Kern, C.L. Developing a university-wide course on sustainability: A critical evaluation of planning and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 106, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierksmeier, C. Reorienting Management Education: From Homo Economicus to Human Dignity. In Business Schools Under Fire. Humanistic Management Education as the Way Forward (19–40); Amann, W., Pirson, M., Dierksmeier, C., von Kimakowitz, E., Spitzeck, H., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirson, M.A.; Lawrence, P.R. Humanism in Business-Towards a Paradigm Shift? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D. Understanding humanistic management. Humanist. Manag. J. 2016, 1, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S. Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, R.; Eizaguirre, A. (Eds.) Virtuous Cycles in Humanistic Management: From the Classroom to the Corporation; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sandri, O.; Holdsworth, S.; Thomas, I. Vignette question design for the assessment of graduate sustainability learning outcomes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, A.; García-Feijoo, M.; Laka, J.P. Defining Sustainability Core Competencies in Business and Management Studies Based on Multinational Stakeholders’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Fadeeva, Z. Competences for Sustainable Development and Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, A.; Alcaniz, L.; García-Feijoo, M. How to Develop the Humanistic Dimension in Business and Management Higher Education ? In Virtuous Cycles in Humanistic Management (3–20); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, F. Dissonance in students’ perceptions of sustainable development and sustainability: Implications for curriculum change. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.A. Reframing management education: A humanist context for teaching in business and society. Interchange 2000, 31, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Shahbudin, A.S.M.; Amran, A. Barriers to achieving a sustainable university in the perspective of academicians. In Proceedings of the 9th AAM International Conference, Penang, Malaysia, 14–16 October 2011; pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, A.D. The critical role of higher education in creating a sustainable future. Plan. High. Educ. 2003, 31, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Euler, D.; Seufert, S. Reflective Executives: A Realistic Goal for Modern Management Education. In Business Schools under Fire. Humanistic Management Education as the Way Forward (212–226); Amann, W., Pirson, M., Dierksmeier, C., von Kimakowitz, E., Spitzeck, H., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Illes, L.M.; Berry, G.R. Creating Breadth in Business Education through Service-Learning. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, W.R.; Moore, J.R.; Bachleda, C.; Canterbury, A.; Franco, C.; Marion, A.; Schreiber, C. Theory of Moral Development of Business Students: Case Studies in Brazil, North America, and Morocco. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caza, A.; Brower, H.H. Mentioning the unmentioned: An interactive interview about the informal management curriculum. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, M.; Fröhlich, L.; Schmidpeter, R. Implementing sustainability as the new normal: Responsible management education—From a private business school’s perspective. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Kumar, M. A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.H.; Corcoran, J.; Pillai, V. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. Introducing Systematic Reviews; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira González, I.; Urrútia, G.; Alonso-Coello, P. Revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis: Bases conceptuales e interpretación. Revista Española de Cardiología 2011, 64, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, M.; Foster, M.J.; Froyd, J.E. Systematic literature reviews in engineering education and other developing interdisciplinary fields. J. Eng. Educ. 2014, 103, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Leal Filho, W.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; de Mattos Nascimento, D.L.; Ávila, L.V. A literature-based review on potentials and constraints in the implementation of the sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro Ortigara, A.; Kay, M.; Uhlenbrook, S. A review of the SDG 6 synthesis report 2018 from an education, training, and research perspective. Water 2018, 10, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Gregorio, V.; Pié, L.; Terceño, A. A systematic literature review of bio, green and circular economy trends in publications in the field of economics and business management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perenyi, A.; Losoncz, M. A systematic review of international entrepreneurship special issue articles. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, L. Entrepreneurship Education and Sustainable Development Goals: A literature Review and a Closer Look at Fragile States and Technology-Enabled Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, J.C.; Cezarino, L.O.; Ferreira, T.C.; Sala, O.T.M.; Unglaub, D.L.; Caldana, A.C.F. Student organizations and Communities of Practice: Actions for the 2030. Agenda for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.C.; Ferreira, T.C.; Borges de Oliveira, M.S.B.; Macini, N.; Caldana, A.C.F. Hidden curriculum in student organizations: Learning, practice, socialization and responsible management in a business school. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicmil, S.; Gough, G.; Hills, S. Insights into responsible education for sustainable development: The case of UWE, Bristol. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, M.; Moore, E. Integrating the Sustainable Development Goals into Teaching, Research, Operations, and Service: A Case Report of Yale University. Sustain. J. Rec. 2019, 12, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, G. Education for Sustainable Development through Short-Term Study Tours. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (ECIE), Genova, Italy, 17–19 September 2015; pp. 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C.; Walmsley, A.; Apostolopoulos, N. Sustainability and entrepreneurship education. A survey of 307 UN HESI signatories. Proc. Eur. Conf. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 2018, 498–506. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, C.J. 100 Global innovative sustainability projects: Evaluation and implications for entrepreneurship education. In Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (ECIE), Paris, France, 18 October 2017; pp. 805–816. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda Suárez, R.; Agüero Contreras, F.C. Globalización, Agenda 2030 e imperativo de la educación superior: Reflexiones. Conrado 2019, 15, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, C.; Buono, A.F.; Howaidy, G. The Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME): The First Decade–What has been achieved? The Next Decade–Responsible Management Education’s Challenge for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleman, W.; Jenks-Jay, N.; Byrne, J. Nested Networks: Transformational Change in Higher Education. Sustain. J. Rec. 2019, 12, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrado, J.C. New pedagogical approaches to induce sustainable development goals. Высшее Образoванuе в Рoссuu 2019, 28, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonetti, G.; Brown, M.; Naboni, E. About the triggering of UN sustainable development goals and regenerative sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 2019, 11, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, M.; Killian, S.; O’Regan, P. Responsible management education: Mapping the field in the context of the SDGs. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weybrecht, G. From challenge to opportunity–Management education’s crucial role in sustainability and the Sustainable Development Goals—An overview and framework. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younie, S.; Audain, J.; Eloff, I.; Leask, M.; Procter, R.; Shelton, C. Mobilising knowledge through global partnerships to support research-informed teaching: Five models for translational research. J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 44, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 17 Sustainable Development Goals | 1. No poverty | 2. Zero hunger | 3. Good health and well-being | 4. Quality education | 5. Gender equality |

| 6. Clean water and sanitation | 7. Affordable and clean energy | 8. Decent work and economic growth | 9. Industry innovation, and infrastructure | 10. Reduce inequalities | 11. Sustainable cities and communities |

| 12. Responsible consumption and production | 13. Climate action | 14. Life below water | 15. Life on land | 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions | 17. Partnerships for goals |

| Search Terms | SCOPUS | WOS | ERIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE ABS KEY | TITLE TOPIC | TITLE DESCRIPTOR ABSTRACT TITLE |

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borges, Cezarino, Ferreira, Sala, Unglaub, and Caldana (2017) [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Borges, Ferreira, Borges de Oliveira, Macini, and Caldana (2017) [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Cicmil, Gough, and Hills (2017) [45] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | --- | --- | Yes |

| Goodall, & Moore (2019) [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kolb, Fröhlich, and Schmidpeter (2017) [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Melles (2015) [47] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Moon, Walmsley, and Apostolopoulos (2018) [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Moon (2017) [49] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Ojeda Suarez and Aguero Contreras (2019) [50] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Parkes, Buono, and Howaidy (2017) [51] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Poleman, Jenks-Jay, and Byrne (2019) [52] | Yes | No | --- | Yes | No | Yes | No | --- | --- | No |

| Quadrado, and Zaitseva (2019) [53] | Yes | No | --- | Yes | No | Yes | No | --- | --- | No |

| Sonetti, Brown, and Naboni (2019) [54] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Storey, Killian, and O’Regan (2017) [55] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Weybrecht (2017) [56] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Younie, Audain, Eloff, Leask, Procter, and Shelton (2018) [57] | Yes | Yes | --- | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | --- | --- | Yes |

| Q1: Is there congruity between stated philosophical perspective and research methodology?; Q2: Is there congruity between research methodology and research questions or objectives?; Q3: Is there congruity between research methodology and methods used to collect data?; Q4: Is there congruity between research methodology, and representation and analysis of data?; Q5: Is there congruity between research methodology and interpretation?; Q6: Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?; Q7: Is the influence of the researcher on the research, or vice-versa, addressed?; Q8: Are participants and their voices adequately represented?; Q9: Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?; Q10: Do conclusions drawn in the research report flow from data analysis or interpretation? | ||||||||||

| Doc. | Researcher Country | Doc. | Journal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46,51,52,56] [45,48,49] [43,44] [29] [47] [55] [50] [53] [54] [57] | USA UK Brazil Germany Australia Ireland Ecuador and Cuba Portugal and Russia Italy, UK, and Denmark UK and South Africa | [29,43,44,45,51,55,56] [47,48,49] [46,52] [50] [53] [54] [57] | Int. J. of Manag. Educ. Proceedings Sust.: The Journal of Record Revista Conrado Vysshee obrazovanie v Rossii Sustainability J. of Educ. for Teaching | |

| (a) | (b) | |||

| Authorship | Type of Document * | Method Explanation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||

| Borges, Cezarino, Ferreira, Sala, Unglaub, and Caldana (2017) [43] | X | Questionnaires to members of nine student associations, including six open-ended questions. Obtained sample was 109 students between the ages of 17 and 25 from the area of Business and Economics. | ||

| Borges, Ferreira, Borges de Oliveira, Macini, and Caldana (2017) [44] | X | Exploratory study carried out with an online questionnaire that included six open-ended questions addressed to nine student associations. Resulting sample was 106 respondents between 17 and 25 years of Economics, Management, and Accounting. | ||

| Cicmil, Gough, and Hills (2017) [45] | X | As their starting point, they took an academic work on models for management education and their recommendations. They critically examined the practice of integrating education for sustainable development (ESD), and the United Nations Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME) (as two complementary schemes) into one particular institution, the University of the West of England, Bristol. They explored the nature and inter-relationships of Holman’s five axioms (epistemological, pedagogical, practical management, social and organizational) to provide a reflective account of their experiences and elucidate a deeper understanding of what responsible education for sustainable development can mean in practice. Their arguments were based on both the literature and practical experience (in PRME/ESD initiatives). | ||

| Goodall, & Moore (2019) [46] | X | From spring 2017 to fall 2018, a team of five student research assistants reviewed the biographies, syllabi, and websites of over 4400 faculty members. Questionnaires were sent to 4400 faculty members and researchers of Yale University to explore how the scholarly activities of higher-education institutions (HEIs) are connected to the SDGs. In 2018, Yale organized and led a half-day event on the role of academia in advancing SDGs on behalf of the IARU (IARU is a network of 11 universities from around the world committed to accelerating progress through collaboration). | ||

| Kolb, Fröhlich, and Schmidpeter (2017) [29] | X | One private business school (BS) in Cologne (Germany) was selected as a case study:

The case study was approached on different levels of analysis:

| ||

| Melles (2015) [47] | X | The author describes two study tours for social impact in Swinburne University (Melbourne, Australia). | ||

| Moon, Walmsley, and Apostolopoulos (2018) [48] | X | The target sample was the 307 HEIs’ signatories to the UN Higher Education Sustainability Initiative (HESI). Analysis of this database revealed which HESIs had committed to which SDGs. They then conducted a follow-up survey via email to identify best practices across HESI signatories. Finally, results were presented to a sample of entrepreneur students and academics for their validation. The main survey instrument included questions on to which SDGs each HESI has signed up, progress with their implementation, faced challenges, and how obstacles were overcome. Moreover, a series of statements from the literature were designed to test the validity of the literature on ESD pedagogy and implications for governance. | ||

| Moon (2017) [49] | X | The study used a data set from Sustainia (2014, 2015, 2016) where several thousand projects are reviewed by experts, and a short-list of the 100 most innovative and inspiring projects across the globe is produced each year. The article analyzed key trends identified across the three years, reviewed the 100 latest projects submitted for 2016 by sector, and discussed implications of key trends and selected projects for HEIs. | ||

| Ojeda Suarez and Aguero Contreras (2019) [50] | X | The descriptions and reflections of the paper are based on analysis of national and international documents and the experiences of the authors in teaching, research, and linkage in the university. | ||

| Parkes, Buono, and Howaidy (2017) [51] | X | The document presented a Special Issue of the International Journal of Management Education that looked at the evolving nature of the UN Global Compact’s initiative focused on BSs (PRME) as it reached the end of its first decade and entered the SDG era. | ||

| Poleman, Jenks-Jay, and Byrne (2019) [52] | X | The authors described three cases of international networks: Regional Centers of Expertise (RCEs), the Global Alliance for Transformative Environmental Change (Global Alliance), and Global Partnerships in Sustainability (GP). | ||

| Quadrado, and Zaitseva (2019) [53] | X | The authors described a teaching project at the higher-education level: the implantation of flipped classroom methodology in specific subjects of the Master’s in Development Practice Program (MDP) at Instituto Politécnico do Porto (Portugal). | ||

| Sonetti, Brown, and Naboni (2019) [54] | X | The authors reviewed a number of multi- and transdisciplinary scholarly works related to sustainability in three areas:

| ||

| Storey, Killian, and O’Regan (2017) [55] | X | The article described the role of different initiatives in the field of Responsible Management Education: UN PRME, membership or affiliation organizations, teaching and learning initiatives, and student-centered or -led groups. | ||

| Weybrecht (2017) [56] | X | The paper proposed a framework in four steps for BSs to help move the SDGs forward. | ||

| Younie, Audain, Eloff, Leask, Procter, and Shelton (2018) [57] | X | The article described translational research as a tool to address improvement challenges in the education sector. | ||

| * Type of document: A: Descriptions, general reflections, or theoretical approaches. B: Qualitative or quantitative studies (with primary-data collection). C: Content analysis. | ||||

| What do They Propose to Deploy SDGs? | What Conclusions do they Draw? | |

|---|---|---|

| Borges, Cezarino, Ferreira, Sala, Unglaub, and Caldana (2017) [43] | Supporting student organizations as they act as true learning communities, connecting people through their shared beliefs, passions and values. The consequence is SDG development among participants. | The development of sustainable-development values at the university occurs in:

|

| Borges, Ferreira, Borges de Oliveira, Macini, and Caldana (2017) [44] | They advocated the promotion of student associations, as they enabled students to create, research, and develop their own transdisciplinary educational content, complementing the formal curriculum of postgraduate courses in management, accounting and economics with the so-called ’hidden curriculum’. | The benefits of participating in a student organization exceeded initial expectations: friendships are made, learning takes place, and skills such as interpersonal relationships, teamwork, and leadership are developed. They are a fertile field for developing social-impact actions, promoting responsibility, ethics, interest in sustainability, and awareness of society. |

| Cicmil, Gough, and Hills (2017) [45] | The dominant belief in an objective epistemology among educators is not effective in addressing the complexity and non-mechanical nature of management practices. Alternative pedagogies may be more beneficial in addressing the challenges of sustainability. Alternative pedagogies and epistemologies encourage educators to:

| It is necessary to:

|

| Goodall and Moore (2019) [46] | Yale SDG project data show that each academic department or school has at least one faculty member whose work relates to the SDGs, and the teaching and research of 44% of Yale University faculty members are connected to at least two SDGs. Thanks to the collected data, interdisciplinary collaboration is being promoted. | Achieving the SDGs requires inclusive and innovative collaboration, and the full potential of HEI involvement in SDGs has not yet been exploited. Through ongoing discussions, innovations and research on this topic, it is possible to design effective strategies for HEIs to contribute to the advancement of SDGs. |

| Kolb, Fröhlich, and Schmidpeter (2017) [29] |

|

|

| Melles (2015) [47] | Short-term study tours allow students to practically engage with sustainability. |

|

| Moon, Walmsley, and Apostolopoulos (2018) [48] | The paper reviewed the progress reported by 307 HEI signatories with their implementation of SDGs, and focuses on governance implications. They propose that:

|

|

| Moon (2017) [49] | Innovative thinking, collaboration and interdisciplinarity are skills needed to tackle SDGs:

| HEIs need to completely transform themselves, in collaboration with practice (going beyond isolated actions). Trends and solutions are transdisciplinary and impact multiple sectors. The transformation would be enhanced by the following actions [52]:

|

| Ojeda Suarez and Aguero Contreras (2019) [50] | The authors described the progress in meeting SDGs in Latin America and the Caribbean, and how globalization processes have impacted higher education. They added reflections related to teaching, research, and linkage with society in order to generate a culture of quality that responds to the interests of society and of the community as support for local sustainability. | The main reflections of the authors related to our research question are the following:

|

| Parkes, Buono, and Howaidy (2017) [51] | There was not specific intervention proposal. |

|

| Poleman, Jenks-Jay, and Byrne (2019) [52] | The authors described the importance of HEIs to be part of interdisciplinary and diverse networks to work jointly for sustainability. | The authors concluded that networks foster the connection between research and practice, promote sustainability solutions at all levels, and empower students to live consistent and engaged lives. |

| Quadrado, and Zaitseva (2019) [53] | They proposed the use of “flipped classroom methodology” for the development of sustainability competencies. | The authors concluded that a flipped classroom

|

| Sonetti, Brown, and Naboni (2019) [54] | HEIs, as education providers, have a crucial role in cultivating sustainability awareness and values within in future generations of citizens, entrepreneurs, and policy makers. | The university could, and should, be the place of transition of values, addressing coordinated actions in two areas:

|

| Storey, Killian, and O’Regan (2017) [55] | This article examined the field of Responsible Management Education (RME) in the context of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. RME includes a range of initiatives and bodies that seek to progress RME but remain diverse. This leads to a certain amount of incoherence in the field, with many overlapping initiatives. The paper described the role of the following initiatives in helping BSs to address SDGs:

|

|

| Weybrecht (2017) [56] | Management education is called to play an important role in the achievement of SDGs, but it seems that it is not doing so at the expected speed. In order for BSs to reflect on where are they today, and set out where and how to move forward, the article proposed a four-step framework:

|

|

| Younie, Audain, Eloff, Leask, Procter, and Shelton (2018) [57] | The article reviewed translational research (TR, “theory-to-practice” research) as a tool to address improvement challenges to the education sector identified by the OECD and UNESCO. It presented the mapping educational specialist knowhow (MESH) system. MESH provides a system for knowledge management (KM) through the communication and dissemination of research for professional practice in education. |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Feijoo, M.; Eizaguirre, A.; Rica-Aspiunza, A. Systematic Review of Sustainable-Development-Goal Deployment in Business Schools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010440

García-Feijoo M, Eizaguirre A, Rica-Aspiunza A. Systematic Review of Sustainable-Development-Goal Deployment in Business Schools. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010440

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Feijoo, María, Almudena Eizaguirre, and Alvaro Rica-Aspiunza. 2020. "Systematic Review of Sustainable-Development-Goal Deployment in Business Schools" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010440

APA StyleGarcía-Feijoo, M., Eizaguirre, A., & Rica-Aspiunza, A. (2020). Systematic Review of Sustainable-Development-Goal Deployment in Business Schools. Sustainability, 12(1), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010440