Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand

Abstract

1. Introduction

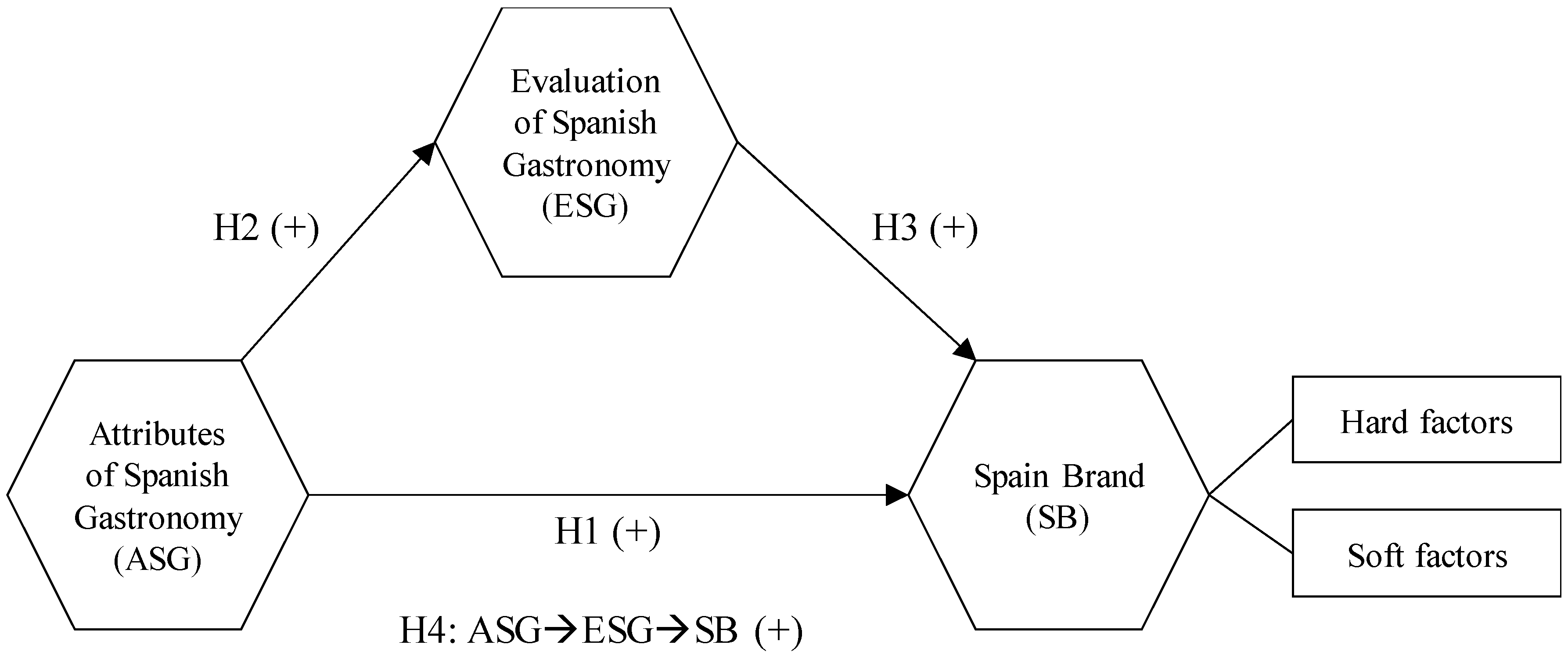

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

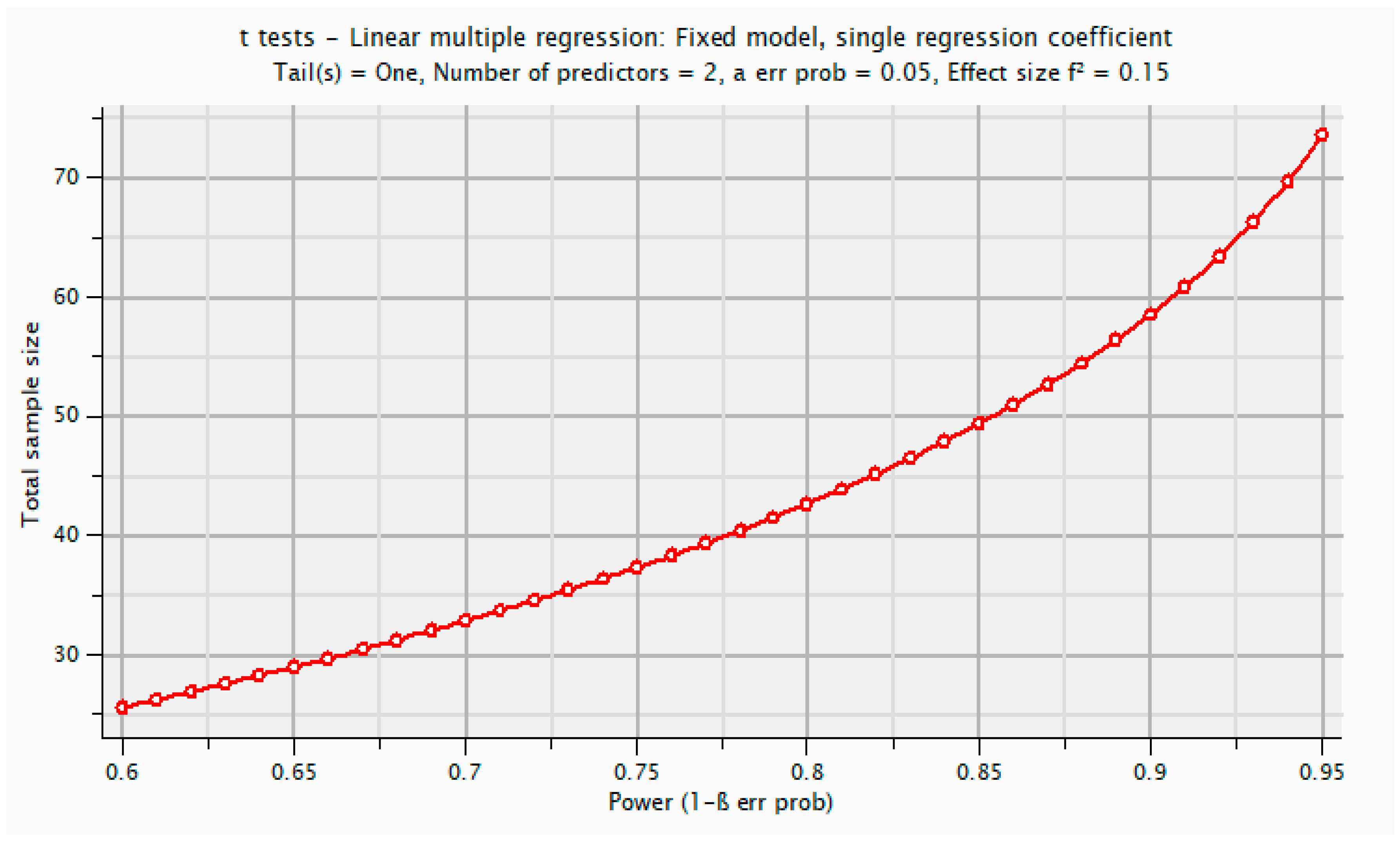

3.1. Sample, Data Collection, and Measures

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model: Individual Item Reliability, Construct Reliability, Convergent Validity and Discriminant Validity, Potential Multicollinearity, and Weights Assessment

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Predictive Ability of the Model

5. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. Tourism Highlights. 2018. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419876 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Aportaciones del Turismo a la Economía Española–Año 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/2GoJzsu (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Burgess, J. Selling places: Environmental images for executives. Reg. Stud. 1982, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Voogd, H. Marketing the city. Concepts, Processes and Dutch Applications. Town Plan. Rev. 1988, 59, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Gertner, D.; Rein, I. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry and Tourism to Cities, States and Nations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Anholt, S. Foreword to the special issue on place branding. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placebrands. Available online: http://www.placebrands.net/principles/principles.html (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Barómetro de la Imagen de España, 7ª oleada. Available online: https://bit.ly/2pFBBRP (accessed on 16 July 2018).

- Symons, M. Gastronomic authenticity and sense of place. In Proceedings of the Ninth Australian Tourism and Hospitality Education Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 10–13 February 1999; CAUTHE: Adelaide, Australia; pp. 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Davis, D.; Paul, G. Segmenting tourism in rural areas: The case of North and Central Portugal. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimothy, S.; Rassing, C.; Wanhill, S. Marketing works: A study of restaurants on Bornholm. Denmark. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppe, M.; Martin, D.; Waalen, J. Toronto’s image as a destination: A comparative importance-satisfaction analysis by origin of visitor. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, C. Food and Gastronomy for Sustainable Place Development: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of Different Theoretical Approaches. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, D. Unfolding and configuring two decades of research and publications on place marketing and place branding. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.A.; Gómez, M.; Molina, A. A destination-branding model: An empirical analysis based on stakeholders. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Lumbers, M.; Eves, A.; Chang, R. Factors influencing tourist food consumption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management, 1st ed.; CABI: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP and UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable—A Guide for Policy Makers; UNEP and UNWTO: Paris, France; Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.M.; Richards, G. Tourism and Gastronomy, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpato, R. Gastronomy as a tourist product: The perspective of gastronomy studies. In Tourism and Gastronomy; Hjalager, A.M., Richards, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel Awards. Available online: https://www.worldtravelawards.com/award-worlds-leading-culinary-destination-2018 (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Balakrishanan, M. Strategic branding of destinations: A framework. Eur. J. Market. 2009, 46, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J.; Horner, S. Consumer Behavior in Tourism; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. Destination Brands: Managing Place Reputation; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bukharov, I.; Berezka, S. The role of tourist gastronomy experiences in regional tourism in Russia. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.; Mittal, B.; Newman, B. Customer Behavior: Consumer Behavior and Beyond; Dryden Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Schewe, C.; Frederick, D. A multi-brand/multiattribute model of tourist state choice. J. Travel Res. 1978, 17, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Pizam, A. The role of awareness and familiarity with a destination: The central Florida case. J. Travel Res. 1995, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.; Im, H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. Towards a model of the Place Brand Web. Tour. Manag. 2014, 48, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnie, K. Country of origin 1965–2004: A literature review. J. Costumer Behav. 2004, 3, 165–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Definitions of place branding-working towards a resolution. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, T.; Rainisto, S. How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations. A Planning Book for Place Branding; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, E.; Font, X.; Andreu, L. Marketing de Destinos Turísticos: Análisis y Estrategias de Desarrollo; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fakeye, P.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the lower Rio Grande valley. J. Travel Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 world cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioural intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlan, J.; Kelly, S. Image formation, information sources and an iconic Australian tourist destination. J. Vacat. Market. 2005, 11, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chernatony, L.; Segal-Horn, S. The Criteria for successful services brands. Eur. J. Market. 2003, 37, 1095–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Heslop, L. Country equity and country branding: Problems and prospect. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, B. How tourists choose their holidays: An analytical framework. In Marketing in the Tourism Industry: The Promotion of Destination Regions; Goodall, B., Ashworth, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1990; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ricolfe, J.S.; Merino, B.R.; Marzo, S.V.; Ferrandis, M.R. Actitud hacia la gastronomía local de los turistas: Dimensiones y segmentación de mercado. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2008, 6, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A.; Corigliano, M.A. Food for tourists. Determinants of an image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummedal, M.; Hall, M. Local food in tourism: An investigation of the New Zealand South Island’s bed and breakfast sector´s use and perception of local food. Tour. Rev. Int. 2006, 9, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Beltrán, F.; López-Guzmán, T.; González Santa Cruz, F. Analysis of the Relationship between Tourism and Food Culture. Sustainability 2016, 8, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Priego, M.A.; García, G.M.; de los Baños, M.; Gomez-Casero, G.; Caridad y López del Río, L. Segmentation Based on the Gastronomic Motivations of Tourists: The Case of the Costa Del Sol (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.P.; Rodríguez, A. El turismo: Globalización, competitividad y sostenibilidad. Mediterraneo Economico 2009, 16, 227–256. [Google Scholar]

- TourEspaña. Available online: https://www.tourspain.es/es-es/con%C3%B3zcanos/plan-estrat%C3%A9gico-de-marketing-18-20 (accessed on 4 February 2019).

- Real Academia de Gastronomía. Available online: http://realacademiadegastronomia.com/my-product/rag-convenio-con-turespana/ (accessed on 14 December 2018).

- Moscardó, G.; Pearce, P. Presenting Destinations: Marketing Host Communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities, 1st ed.; Singh, S., Timothy, D.J., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CABI: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Boyne, S.; Hall, D. Place promotion through food and tourism: Rural branding and the role of websites. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roldán, J.L.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. Variance-based structural equation modeling: Guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; Roldán, J., Sanchez-Franco, M.J., Eds.; IGI Global: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Inbakaran, R.; Reece, J. Consumer research in the restaurant environment, Part 1: A conceptual model of dining satisfaction and return patronage. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 11, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in Tourism—Attraction and Impediment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 755–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Mitchell, R. We are what we eat: Tourism, culture and the globalization and localization of cuisine. Tourism Culture and Communication. 2000, 2, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-Florencio, R. Con la Salsa de su Hambre. Los Extranjeros Ante la Mesa Hispana; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrés, S. Alimentación y Alimentación y cultura. La alimentación de los inmigrantes magrebíes de Sevilla durante el ramadán: Un ejemplo de alimentación mediterránea. In Proceedings of the International Congress of the National Museum of Anthropology, Seville, Spain, 1998; La Val de Onsera, Huesca: Seville, Spain, 1999; pp. 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter, R. Turismo y Patrimonio Gastronómico: Una perspectiva; CIET: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann, T.; Meiseberg, B.; Ritz, C. Superstar Effects in Deluxe Gastronomy–An Empirical Analysis of Value Creation in German Quality Restaurants. Kyklos 2009, 62, 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surlemont, B.; Johnson, C. The Role of Guides in Artistic Industries: The Special Case of the ‘‘Star System’’ in the Haute-Cuisine Sector. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2005, 15, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K. The Role of Destination Image in Tourism: A Review and Discussion. Tour. Rev. 1990, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action; Kent Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Tourists’ characteristics and the perceived image of tourist destinations: A quantitative analysis—A case study of Lanzarote, Spain. Tourism Management. 2004, 25, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.B. The Meaning and Measurement of Destination Image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, S.; McClear, K.W. A model of Destination Image Formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 25, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.; Sánchez, M.I.; Sánchez, J. Tourism image, evaluation variables and after purchase behavior: Inter-relationship. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez-Amado, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A. Development and update of guidelines to perform and report partial least squares path modeling in Information Systems research. Proceedings 2017, 86, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Felipe, C.M.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Impact of Organizational Culture Values on Organizational Agility. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.T.; Campbell, D.E.; Thatcher, J.B.; Roberts, N.H. Operationalizing Multidimensional Constructs in Structural Equation Modeling: Recommendations for IS Research. CAIS 2012, 30, 367–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningsted, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage publications: California, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H.; Berge, J.M.T. Psychometric theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S.; Straub, D.; Rai, A. Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G. To explain or to predict? Stat. Sci. 2010, 25, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, P.; Vinzi, V.E.; Lauro, C. Predictive Path Modeling Through PLS and Other Component-Based Approaches: Methodological Issues and Performance Evaluation. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Latan, H., Noonan, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Evermann, J.; Tate, M. Assessing the predictive performance of structural equation model estimators. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4565–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Authors |

|---|---|

| Attributes of Spanish Gastronomy (ASG): First order construct (Mode A). | Muñoz and Rodríguez [48]; Ricolfe et al. [42]; Kivela et al. [57]; Hjalager and Corigliano [43]; Cohen and Avieli [58]; Nummedal and Hall [45]; Mak et al. [16]; Hall and Mitchell [59]. |

| Evaluation of Spanish Gastronomy (ESG): Single-item variable. | Hall and Mitchell [59]; Nuñez-Florencio [60]; Tarrés [61]; Schlüter [62]; Ehrmann et al. [63]; Surlemont and Johnson [64]. |

| Spain Brand (SB): second order construct (Mode B) shaped by two dimensions (Hard and Soft factors). | Boyne and Hall [52]; Kastenholz et al. [10]; Gyimothy et al. [11]; Joppe et al. [12]; Muñoz and Rodríguez [48]; Chon [65]; Assael [66]; Papadopoulos and Heslop [40]; Goodall [41]; Fakeye and Crompton [35]; Kotler et al. [5]; Beerli and Martín [67]; Echtner and Ritchie [68]; Chen and Tsai [37]; Baloglu and McClear [69]; Bigné et al. [70]. |

| Construct/Indicators | Outer Loadings | Weights | VIF | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes of the Spanish gastronomy | 0.888 | 0.902 | 0.509 | |||

| P1_1: Tasty | 0.737 | 0.179 | 2.030 | |||

| P1_2: Varied | 0.770 | 0.176 | 1.968 | |||

| P1_3: Traditional | 0.590 | 0.116 | 1.496 | |||

| P1_4: Original | 0.765 | 0.155 | 2.059 | |||

| P1_5: Sophisticated | 0.779 | 0.169 | 2.248 | |||

| P1_6: Healthy | 0.665 | 0.148 | 1.595 | |||

| P1_7: International | 0.657 | 0.127 | 1.687 | |||

| P1_8: Exclusive | 0.647 | 0.133 | 1.603 | |||

| P1_9: Quality | 0.781 | 0.187 | 2.031 | |||

| Evaluation of the Spanish gastronomy | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |||

| P2: Evaluation | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||

| Soft factors | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |||

| P3_1: Culture | 0.734 | 0.393 | 1.264 | |||

| P3_2: Partying | 0.421 | 0.139 | 1.157 | |||

| P3_3: Leisure | 0.567 | 0.229 | 1.287 | |||

| P3_6: Good weather | 0.374 | 0.113 | 1.120 | |||

| P3_7: Food/drink | 0.855 | 0.562 | 1.329 | |||

| Hard factors | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | |||

| P3_4: Technology | 0.918 | 0.387 | 3.496 | |||

| P3_5: Innovation | 0.908 | 0.402 | 3.320 | |||

| P3_8: Business | 0.775 | 0.361 | 1.439 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Attributes of the Spanish Gastronomy | Hard | Soft | Evaluation of the Spanish Gastronomy |

| Attributes of the Spanish gastronomy | ||||

| Hard | 0.414 | |||

| Soft | 0.726 | 0.461 | ||

| Evaluation of the Spanish gastronomy | 0.760 | 0.282 | 0.577 | |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficient | t-Statistic | p-Value | 95% BCCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Attributes of the Spanish gastronomy → Spain Brand | 0.481(Sig.) | 7.863 | 0.000 | [0.354; 0.596] |

| H2: Attributes of the Spanish gastronomy → Evaluation of the Spanish gastronomy | 0.727(Sig.) | 28.508 | 0.000 | [0.672; 0.773] |

| H3: Evaluation of the Spanish gastronomy → Spain Brand | 0.235(Sig.) | 3.495 | 0.000 | [0.105; 0.369] |

| H4: [Indirect effect] Attributes of the Spanish gastronomy → Spain Brand | 0.171(Sig.) | 3.375 | 0.001 | [0.075; 0.275] |

| Coefficient of determination: R2 Spain Brand = 0.451; R2 Evaluation of the Spanish gastronomy = 0.529 | ||||

| Construct prediction summary | ||||

| Q2 | ||||

| Spain Brand | 0.336 | |||

| Dimension prediction summary | ||||

| Q2 | ||||

| Soft | 0.409 | |||

| Hard | 0.156 | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vázquez-Martinez, U.J.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092696

Vázquez-Martinez UJ, Sanchís-Pedregosa C, Leal-Rodríguez AL. Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand. Sustainability. 2019; 11(9):2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092696

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez-Martinez, Ulpiano J., Carlos Sanchís-Pedregosa, and Antonio L. Leal-Rodríguez. 2019. "Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand" Sustainability 11, no. 9: 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092696

APA StyleVázquez-Martinez, U. J., Sanchís-Pedregosa, C., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2019). Is Gastronomy A Relevant Factor for Sustainable Tourism? An Empirical Analysis of Spain Country Brand. Sustainability, 11(9), 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092696