Identifying Factors Associated with Food Losses during Transportation: Potentials for Social Purposes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

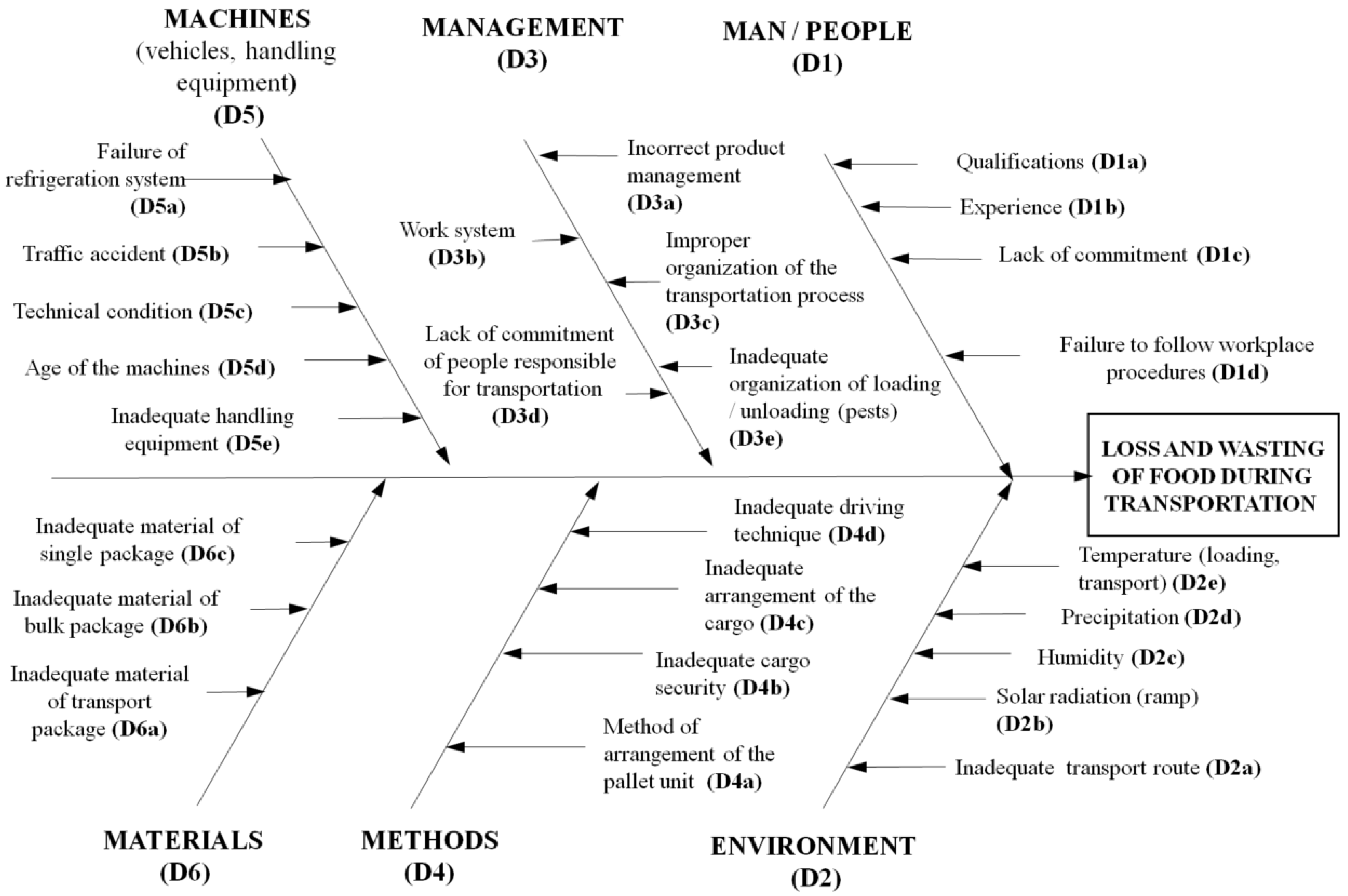

3.1. Identification of the Causes of Loss and Waste of Food at the Stage of Transportation

3.2. Analysis of Hazards and Risks of Dairy Product Quality Deterioration during Transportation

3.3. Verification Identified RP on the Basis of a Survey

3.4. Confirmation Identified RP on the Basis of a Survey

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Please indicate the stages at which the driver of the transport unit is responsible for the goods.

- Please indicate what type of exposure was the reason why the recipient did not accept the goods transported by your transport unit (even a small quantity).Please indicate the frequency and mass of such cases.

- At which of the above-mentioned stages did the most frequent mechanical damage of transported goods occur.

- Please describe the mechanical damage that caused the rejection of the goods by the recipient (specify the number of cases together with the weight/number of damaged goods).

- Did contamination of the contents of one pallet included in the pallet unit due to the damage of a single package (the remaining pallets are clean) result in the recipient not accepting the entire transport package (pallet unit)?

- Please indicate what happens to mechanically damaged goods not accepted by the recipient.

- Does mechanical damage (dents or damage to single packages) occur in every transport?

- Please indicate which products of the dairy cooperative, in your opinion, are most often subject to mechanical damage during transport (and not accepted by the recipient).

- Does the customer check the temperature inside the loading space of the vehicle transporting the finished products to the dairy cooperative?

- Please indicate the temperature ranges in the load compartment which are not accepted by the recipient (multiple answers possible).

- How often is the temperature inside the load compartment taken and recorded during the transport of finished products of the dairy cooperative?

- Does the consignee require the driver to show records of the temperature inside the load compartment of the vehicle transporting the finished products of the dairy cooperative?

- Do cases of interruption of the cold chain occur during the transport of the dairy cooperative’s products?

- Please indicate the reasons for failing to maintain the cooling temperature in the load compartment of your company’s vehicle (please indicate the frequency of such cases).

- Please indicate the number of breakdowns and accidents that prevented the delivery of goods.

- Please indicate the actions taken in the event that it is not possible to continue the route (breakdown/minor accident).

- On the basis of which documents is compensation paid to your company by your insurance company?

- Weight of products disposed of (kg).

References

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards a Common Methodology and Minimum Quality Requirements for the Uniform Measurement of Levels of Food Waste (Draft). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/initiatives/ares-2018-705329_en (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources; Summary Report; Natural Resources Management and Environment Department: Rome, Italy, 2013; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; Report of the project FUSIONS granted by the European Commission (FP7); IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; Available online: https://www.eu-fusions.org/phocadownload/Publications/Estimates of European food waste levels.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Monier, V.; Mudgal, S.; Escalon, V.; O’Connor, C.; Gibon, T.; Anderson, G.; Montoux, H. Preparatory Study on Food Waste Across EU27. 2010. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/bio_foodwaste_report.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2016).

- Jedermann, R.; Nicometo, M.; Uysal, I.; Lang, W. Reducing food losses by intelligent food logistics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20130302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajewski, K.; Wrzosek, M.; Lipińska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Bilska, B. Logistyka odzysku produktów mleczarskich w świetle analizy ryzyka strat w procesach dystrybucji. Logistyka 2014, 6, 13482–13488. [Google Scholar]

- Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Bilska, B.; Krajewski, K.; Wrzosek, M.; Trafiałek, J. Projekt MOST jako innowacyjne rozwiązanie dla zakładów produkcji i dystrybucji żywności. In Innowacyjne Rozwiązania w Technologii Żywności i Żywieniu Człowieka; Tarko, T., Drożdż, I., Najgebauer-Lejko, D., Duda-Chodak, A., Eds.; Oddział Małopolski PTTŻ: Kraków, Polska, 2016; pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzosek, M.; Bilska, B.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Krajewski, K. Zastosowanie analizy ryzyka do opracowania innowacyjnego systemu ograniczania strat i marnowania żywności w handlu detalicznym (system MOST). Żywność Nauka Technologia Jakość 2017, 24, 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Salihoglu, G.; Salihoglu, N.K.; Ucaroglu, S.; Banar, M. Food loss and waste management in Turkey. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Swedish Institute for Food and Biotechnology (SIK): Gothenburg, Sweden; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: www.fao.org/3/mb060e/mb060e.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2018).

- Raak, N.; Symmank, C.; Zahn, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Rohm, H. Processing- and product-related causes for food waste and implications for the food supply chain. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałka, A. Refrigerated food transport in Poland. Autobusy 2018, 12, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, A.; Clement, J.; Kornum, N.; Bucatariu, C.; Magid, J. Addressing food waste reduction in Denmark. Food Policy 2014, 49, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstad, S.S.; Andersson, T. Food waste minimization from a life-cycle perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 147, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuseppe, A.; Mario, E.; Cinzia, M. Economic benefits from food recovery at the retail stage: An application to Italian food chains. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midgley, J.L. The logics of surplus food redistribution. J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 2014, 57, 1872–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaholias, E.; Thompson, K.; Every, D.; Dawson, D. Charity starts… at work? Conceptual foundations for research with businesses that donate to food redistribution organisations. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7997–8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Wrzosek, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Krajewski, K. Risk of food losses and potential of food recovery for social purposes. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, L. A new model of Ishikawa diagram for quality assessment. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 161, Proceedings of the 20th Innovative Manufacturing Engineering and Energy Conference, Kozani, Greece, 23–25 September 2016; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Antoszkiewicz, J.D. Metody heurystyczne w procesach przedsiębiorczych. In Współczesne Dylematy Badań nad Przedsiębiorczością; Kosała, M., Urbaniec, M., Żur, A., Eds.; Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie: Kraków, Polska, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius. Food Hygiene (Basic Texts), 4th ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a1552e/a1552e00.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- Tomaszewska, M.; Lipińska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Grodzicki, A. Analiza strat na etapie transportu mleka i jego przetworów w wybranych spółdzielniach mleczarskich z Wielkopolski. In Roczniki Naukowe Stowarzyszenia Ekonomistów Rolnictwa i Agrobiznesu; Wieś Jutra Sp. z o.o.: Warszawa, Polska, 2016; Tom XVIII, Zeszyt 3; pp. 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, D. Food quality, storage, and transport. In Reference Module in Food Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.03336-9 (accessed on 20 February 2016).

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 Laying Down Specific Hygiene Rules for Food of Animal Origin (Bulletin of Legal Acts L 139 dated 30.04.2004). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004R0853&from=EN (accessed on 24 February 2017).

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Technology Options for Feeding 10 Billion People. In Options for Cutting Food Waste; Science and Technology Options Assessment (STOA): Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/513515/IPOL-JOIN_ET%282013%29513515_EN.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- European Commission and Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General. Labelling: Competitiveness, Consumer Information and Better Regulation for the EU. A DG SANCO Consultative Document; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2006; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/labelling-nutrition_better-reg_competitiveness-consumer-info_en.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2016).

- The European Consumers’ Organisation BEUC. Report on European Consumers’ Perceptions of Foodstuffs Labeling. Results of Consumer Research Conducted on Behalf of BEUC from February to April 2005. Available online: https://www.vzbv.de/sites/default/files/mediapics/beuc_foodstuffs_labelling_09_2005.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2016).

- Bandara, B.E.S.; De Silva, D.A.M.; Maduwanthi, B.C.H.; Warunasinghe, W.A.A.I. Impacts of Food Labeling Information on Consumer Purchasing Decision: With Special Reference to Faculty of Agricultural Sciences. Procedia Food Sci. 2016, 6, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.T.; Brown, J.H.; Burger, J.R.; Flanagan, T.P.; Fristoe, T.S.; Mercado-Silva, N.; Nekola, J.C.; Okie, J.G. Food Spoilage, Storage, and Transport: Implications for a Sustainable Future. BioScience 2015, 65, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, G.L. Food Packaging: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). International Transportation Agreement of Perishable Foodstuffs and Special Means of Transport Intended for These Transports (ATP). Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/main/wp11/ATP_publication/ATP-2016e_-def-web.pdf2015 (accessed on 18 February 2016).

- Li, Z.; Thomas, C. Quantitative evaluation of mechanical damage to fresh fruits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 35, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; de-Magistris, T. Consumer preferences for food labeling: What ranks first? Food Control 2016, 61, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilska, B.; Piecek, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.A. Multifaceted Evaluation of Food Waste in a Polish Supermarket—Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompay, T.J.L.; Deterink, F.; Fenko, A. Healthy package, healthy product? Effects of packaging design as a function of purchase setting. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencja Rynku Rolnego. Market Prices Forecast of Basic Agri-Food Products 2016. Available online: http://www.arr.gov.pl/data/00165/prognoza_16_kw_06.pdf. (accessed on 16 April 2016).

| Stage of Transportation | Category * | Factor (Type of Exposure) | Cause | Effect | Significance of Hazard **/RP *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading/transportation/unloading | S/NV/SV/A | What event had an impact on the goods exclusion from the market (mechanical, environmental, chemical, biological) | On the basis of the Ishikawa diagram | Type of damage—indication of recoverable products | 1, 2, 3/YES, NO |

| Number of Transport Units | Load Capacity of Transport Units | Number of Trips Per Month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Average * | Total ** | Average * | Total | Average * |

| 204 pcs. | 4.7 pcs. | 4859.5 tons | 107.85 tons | 1.617 | 35.15 |

| Stage of Transportation | Category | Factor (Type of Exposure) | Cause (on the Basis of Ishikawa Diagram) | Effect | Significance of Hazard/RP * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading/unloading from the means of transportation | A | Deformation of transport package (pallet unit) or bulk container due to improper arrangement placement of goods and/or security of transportation package (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D3b, D3e, D4a | Goods unattractive for trade but still valuable | 1/YES |

| Loading/unloading from the means of transportation | A | Damage of a single package, dented/deformed cardboard, cup, PET bottles without breaking the protective barrier (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D3b, D3e, D4a | Goods unattractive for trade but still valuable | 1/YES |

| Loading/unloading to/from the means of transportation | A | Contamination of the contents of the pallet with the contents of the damaged single package (breaking of the continuity of the single package, which is part of the pallet) contained in the transportation package (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D3b, D3e, D4a | The product is unattractive for trade but valuable after carrying out proper cleaning/washing procedures Exception is a single package with broken protective barrier | 1/YES |

| Loading/unloading to/from the means of transportation | S | The damage of a single package (cardboard, foil bag, mug, bar, aluminum foil, PET bottle) causing the breakage of the protective barrier (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D3b, D3e, D4a, D6a, D6b, D6c | Breakage the protective barrier of a single package, the goods are dangerous for the consumer, Possible risks of biological, physical and chemical nature | 3/NO |

| Loading/unloading to/from the means of transportation | S SV | Failure to meet loading/unloading conditions (incorrect temperature and operating time) (environmental) | D1d, D2b, D2c, D2d, D2e, D3a, D3b, D3d | Dangerous product-proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms, Change of sensory properties | 3/NO |

| Transportation the cargo by means of transportation | A | Damage of transportation package (pallet unit) of the following type: Shifting of bulk packages in the vertical plane of the pallet due to improper protection of the transport package Dented deformation of carton, cup, PET bottles due to improper arrangement of goods and/or security of transport packages during transportation (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D4d, D5b, D5c, D5d, D5e | Goods unattractive for trade but valuable | 1/YES |

| Transportation the cargo by means of transportation | A | Contamination of the contents of the pallet with the contents of the damaged single package (breakage of the continuity of the single package, which is part of the pallet), as a part of transport package (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D4d, D5b, D5c, D5d, D5e | The product is unattractive for trade, but valuable after carrying out proper cleaning/washing procedures Exception is a single package with broken protective barrier | 1/YES |

| Transportation the cargo by means of transportation | S | Damage of a single package (cardboard, foil bag, mug, bar, aluminum foil, PET bottle) causing the breakage of the protective barrier (mechanical) | D1a, D1b, D1c, D1d, D4d, D5b, D5c, D5d, D5e | Breaking the protective barrier of a single package, dangerous for the consumer, Possible risks of biological, physical and chemical nature | 3/NO |

| Transportation the cargo by means of transportation | S SV | Nonobservance of the correct environment/environment, improper organization of work) (environmental) | D2a, D3c, D3d, D5b, D5c, D5d | Dangerous product-proliferation of pathogenic microorganisms, Change of sensory value | 3/NO |

| Type of Exposure | Number of Cases in the Analyzed Period | Estimated Monthly Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | 46 (17 carriers) | 2 |

| Environmental | 2 (1 carrier) | 0.08 |

| Chemical | 0 | 0 |

| Biological | 0 | 0 |

| Others (short terms) | 7 (2 carriers) | 0.3 |

| Type of Mechanical Damage | Share % | Weight of the Damaged Goods [kg/2 Years] | Average Monthly Value [kg] |

|---|---|---|---|

| No description | 22 | 21,600.5 | 900 |

| Deformation of a single or bulk package | 31 | 1012 | 42.2 |

| Tilting of transport package (pallet unit) | 9.5 | 1500 | 62.5 |

| Breaking up of package, bulk or transport | 37.5 | 1507 | 62.8 |

| RP | Number of Cases/2 Years | Weight (kg/2 Years) |

|---|---|---|

| Loading into the means of transportation | 12 | 115 |

| Transportation | 19 | 12,500 |

| Unloading at the recipient’s place | 16 | 12,355 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lipińska, M.; Tomaszewska, M.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Identifying Factors Associated with Food Losses during Transportation: Potentials for Social Purposes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072046

Lipińska M, Tomaszewska M, Kołożyn-Krajewska D. Identifying Factors Associated with Food Losses during Transportation: Potentials for Social Purposes. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072046

Chicago/Turabian StyleLipińska, Milena, Marzena Tomaszewska, and Danuta Kołożyn-Krajewska. 2019. "Identifying Factors Associated with Food Losses during Transportation: Potentials for Social Purposes" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072046

APA StyleLipińska, M., Tomaszewska, M., & Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. (2019). Identifying Factors Associated with Food Losses during Transportation: Potentials for Social Purposes. Sustainability, 11(7), 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072046