Conceptualising the Factors that Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

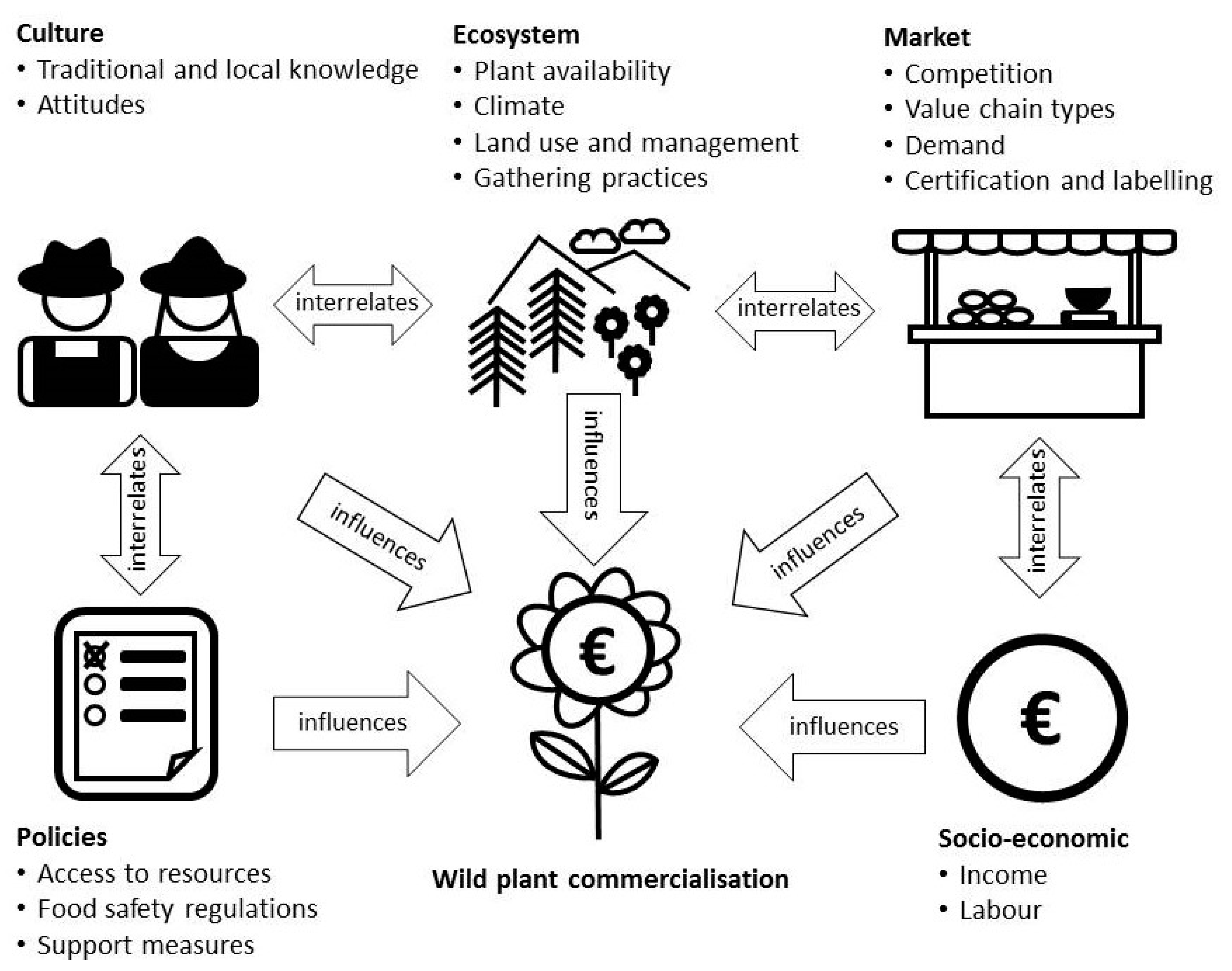

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Ecosystem

2.1.1. Availability

2.1.2. Climate

2.1.3. Land Use and Management

2.1.4. Gathering Practices

2.2. Policies

2.2.1. Access to Resources

2.2.2. Food Safety Regulations

2.2.3. Support Measures

2.3. Socio-Economic

2.3.1. Income

2.3.2. Labour

2.4. Market

2.4.1. Competition

2.4.2. Value Chain Types

2.4.3. Demand

2.4.4. Certification and Labelling

2.5. Culture

2.5.1. Traditional and Local Knowledge

2.5.2. Attitudes

2.6. Interactions between Factors

3. Methods

3.1. Field Site

3.2. Literature Review

3.3. Sample

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Ecosystem

4.1.1. Availability

4.1.2. Climate

4.1.3. Land Use and Management

4.1.4. Gathering Practices

4.2. Policies

4.2.1. Access to Resources

4.2.2. Food Safety Regulations

4.2.3. Support Measures

4.3. Socio-Economic

4.3.1. Income

4.3.2. Labour

4.4. Market

4.4.1. Competition

4.4.2. Value Chain Types

4.4.3. Demand

4.4.4. Certification and Labelling

4.5. Culture

4.5.1. Traditional and Local Knowledge

4.5.2. Attitudes

5. Discussion

5.1. Supporting and Limiting Factors

5.2. Conceptual Framework

6. Conclusions

- promoting organic farming as measure to support wild plant gathering;

- limiting pesticide driftage;

- facilitating access to gathering sites and their organic certification;

- holding a review of legal restrictions;

- providing information to consumers about the additional value of organic certification of wild plants;

- continuing to provide easy access to training for producers;

- building on the trend for wild, regional and healthy foods;

- acknowledging cultural values in wild plant gathering;

- promoting the transmission of knowledge about wild plant gathering.

- supporting wild plant product development;

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ludvig, A.; Tahvanainen, V.; Dickson, A.; Evard, C.; Kurttila, M.; Cosovic, M.; Chapman, E.; Wilding, M.; Weiss, G. The practice of entrepreneurship in the non-wood forest products sector: Support for innovation on private forest land. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 66, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živojinović, I.; Nedeljković, J.; Stojanovski, V.; Japelj, A.; Nonić, D.; Weiss, G.; Ludvig, A. Non-timber forest products in transition economies: Innovation cases in selected SEE countries. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 81, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, S.A.; Wynberg, R.P.; McLain, R. The State of NTFP Policy and Law. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 343–365. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, S.A.; McLain, R.; Wynberg, R.P. Introduction. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, B.M. What isn’t an NTFP? Int. Forest. Rev. 2003, 5, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, A.; Emery, M.R. NTFPs in Scotland: Changing Attitudes to Access Rights in a Reforesting Land. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Schunko, C.; Vogl, C. Is the Commercialization of Wild Plants by Organic Producers in Austria Neglected or Irrelevant? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imami, D.; Ibraliu, A.; Fasllia, N.; Gruda, N.; Skreli, E. Analysis of the Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Value Chain in Albania. Gesunde Pflanz. 2015, 67, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasser, S.; Schunko, C.; Vogl, C.R. Gathering "tea"--from necessity to connectedness with nature. Local knowledge about wild plant gathering in the Biosphere Reserve Grosses Walsertal (Austria). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunko, C.; Vogl, C.R. Organic farmers use of wild food plants and fungi in a hilly area in Styria (Austria). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Román, M.; Boa, E. The Marketing of Lactarius deliciosus in Northern Spain. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, V.H. Use and Potential of Wild Plants in Farm Households; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J. (Eds.) The world of Organic Agriculture—Statistics and Emerging Trends 2018; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FIBL) and IFOAM—Organics International: Frick, Switzerland; Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.; Tardío, J.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Morales, R.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Weeds and Food Diversity: Natural Yield Assessment and Future Alternatives for Traditionally Consumed Wild Vegetables. J. Ethnobiol. 2014, 34, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, T.; Pirożnikow, E.; Dumanowski, J.; Łuczaj, Ł. Juniper Beer in Poland: The Story of the Revival of a Traditional Beverage. J. Ethnobiol. 2014, 34, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, M.; Saastamoinen, O.; Turtiainen, M. Changes in wild berry picking in Finland between 1997 and 2011. Scand. J. For. Res. 2013, 28, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Pettenella, D.; Vidale, E. Income generation from wild mushrooms in marginal rural areas. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. The changing ethnoecological cobweb of white truffle (Tuber mangnatum Pico) gatherers in South Piedmont, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilz, D.; Molina, R. Commercial harvests of edible mushrooms from the forests of the Pacific Northwest United States: Issues, management, and monitoring for sustainability. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 155, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, M.R.; Barron, E.S. Using Local Ecological Knowledge to Assess Morel Decline in the U.S. Mid–Atlantic Region. Econ. Bot. 2010, 64, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pandey Ashok, K.; Ticktin, T. (Eds.) Ecological Sustainability for Non-Timber Forest Products; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł.J.; Dumanowski, J.; Köhler, P.; Mueller-Bieniek, A. The Use and Economic Value of Manna grass (Glyceria) in Poland from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Hum. Ecol. 2012, 40, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Aceituno, L.; Morales, R.; Tardio, J. Fruit production of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) in two Spanish forests. Forestry 2011, 84, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Local Knowledge and Management of the Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis L.) in Northern Spain: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation. Am. Fern J. 2009, 99, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, A.R.; Bürgener, M. Laws and Policies Impacting Trade in NTFPs. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Seeland, K.; Staniszewski, P. Indicators for a European Cross-country State-of-the-Art Assessment of Non-timber Forest Products and Services. Small-Scale For. 2007, 6, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, P.; Pierce, A.R.; Laird, S.A.; Guillen, A. Tapping the Green Market: Certification and Management of Non-Timber Forest Products; Earthscan: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peintner, U.; Schwarz, S.; Mešić, A.; Moreau, P.-A.; Moreno, G.; Saviuc, P. Mycophilic or mycophobic? Legislation and guidelines on wild mushroom commerce reveal different consumption behaviour in European countries. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, R.T.; Saastamoinen, O. NTFP Policy, Access to Markets and Labour Issues in Finland: Impacts of Regionalization and Globalization on the Wild Berry Industry. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Grivins, M.; Tisenkopfs, T. Benefitting from the global, protecting the local: The nested markets of wild product trade. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Tedder, S.; Brigham, T.; Cocksedge, W.; Hobby, T. Policy Gaps and Invisible Elbows: NTFPs in British Columbia: Mitchell, Sinclair Tedder, Tim Brigham, Wendy Cocksedge and Tom Hobby. In Wild Product Governance; Laird, S.A., McLain, R., Wynberg, R.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, M.S.; Blatner, K.A.; Cohn, P.J. Somewhere Between: Social Embeddedness and the Spectrum of Wild Edible Huckleberry Harvest and Use. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltola, R.; Hallikainen, V.; Tuulentie, S.; Naskali, A.; Manninen, O.; Similä, J. Social licence for the utilization of wild berries in the context of local traditional rights and the interests of the berry industry. Barents Stud. Peoples Economies Politics 2014, 1, 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Karousou, R.; Deirmentzoglou, S. The herbal market of Cyprus: Traditional links and cultural exchanges. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voces, R.; Diaz-Balteiro, L.; Alfranca, Ó. Demand for wild edible mushrooms. The case of Lactarius deliciosus in Barcelona (Spain). J. For. Econ. 2012, 18, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keča, L.; Keča, N.; Rekola, M. Value chains of Serbian non-wood forest products. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivins, M. A comparative study of the legal and grey wild product supply chains. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: The disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper-Pakosz, R.; Pietras, M.; Łuczaj, Ł. Wild and native plants and mushrooms sold in the open-air markets of south-eastern Poland. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Zovkokončić, M.; Miličević, T.; Dolina, K.; Pandža, M. Wild vegetable mixes sold in the markets of Dalmatia (southern Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitta, N.; Floriani, M. Nationalization and Globalization Trends in the Wild Mushroom Commerce of Italy with Emphasis on Porcini (Boletus edulis and Allied Species). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, P.; Pierce, A.R.; Laird, S.A.; Robinson, D. Beyond Timber: Certification and Management of Non-Timber Forest Products; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Pettenella, D.; Maso, D. ‘Net-System’ Models Versus Traditional Models in NWFP Marketing: The Case of Mushrooms. Small-Scale For. 2009, 8, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Scaltriti, B.; Cianfaglione, K.; Quave, C.L. Local knowledge on plants and domestic remedies in the mountain villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTAT. South Tyrol in Figures; Autonomous Province of South Tyrol Provincial Statistics Institute (ASTAT): Bolzano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Autonome Provinz Bozen-Südtirol. Agrar- & Forstbericht 2017; Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol, Ressort Landwirtschaft, Forstwirtschaft, Zivilschutz und Gemeinden: Bolzano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vereinigung Südtiroler Kräuteranbauer Homepage. Available online: www.suedtirol-kraeuter.it (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Bernard, R.H. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 5th ed.; Altamira Press: Plymouth, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; Social Science Open Access Repository (SSOAR), 2014. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Shackleton, C.M.; Pandey Ashok, K.; Ticktin, T. Ecologically sustainable harvesting of non-timber forest products: Disarming the narrative and the complexity. In Ecological Sustainability for Non-Timber Forest Products; Shackleton, C.M., Pandey Ashok, K., Ticktin, T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 260–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colby, K.T. Public Access to Private Land—Allemansrätt in Sweden. Landsc. Und Urban Plan. 1988, 15, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Acosta-Naranjo, R.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Domínguez, P.; Garnatje, T.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Molina-Bustamante, M.; Molina, M.; et al. From famine foods to delicatessen: Interpreting trends in the use of wild edible plants through cultural ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunko, C.; Grasser, S.; Vogl, C.R. Explaining the resurgent popularity of the wild: Motivations for wild plant gathering in the Biosphere Reserve Grosses Walsertal, Austria. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2015, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, S.; Ren, Y.; Ma, X.; Cao, Y. Determinants of engagement in non-timber forest products (NTFPs) business activities: A study on worker households in the forest areas of Daxinganling and Xiaoxinganling Mountains, northeastern China. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet Quang, D.; Nam Anh, T. Commercial collection of NTFPs and households living in or near the forests. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferket, B.V.A.; Degrande, A.; van Damme, P. Improving Commercialization of Cola spp. in Cameroon – Applying Lessons from NTFPs in a Context of Domestication. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynberg, R.P.; van Niekerk, J. Commercialization and sustainability: When can they coexist? In Ecological Sustainability for Non-timber Forest Products; Shackleton, C.M., Pandey Ashok, K., Ticktin, T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, S.A.; McLain, R.; Wynberg, R.P. (Eds.) Wild Product Governance; Earthscan: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Factor Category | Factor | Perceptions by Farmers | Previous Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting Commercialisation | Limiting Commercialisation | |||

| Ecosystem | Plant availability | Plant resources abundantly available | Fluctuating availability of plant resources | Abundance of targeted wild plants is a precondition for commercialisation; fluctuating or decreasing availability limits commercialisation [14,15,16,17,18] |

| Climate | n/a | n/a | Mushroom (and berry) populations are especially negatively affected by climate change [16,18,19,20] | |

| Land use and management | Organic farming positively relates to diversity of wild plant species available; continuing use of pastures supports the availability of certain plant species | Continuing use of pastures, fertilisation of pastures, elimination of landscape elements, mowing with machinery, elimination of intermediate hosts of pathogens all limit the diversity of plant species available; pesticide drift contaminates wild plant species gathered | Land use changes are among the greatest threats to the abundance and thus commercialisation of wild plant species; land management can support or limit commercialisation [8,11,18,19,20,21,22,23] | |

| Gathering practices | n/a | n/a | Unsustainable harvesting techniques can limit availability and thus commercialisation, especially of herbal wild plant species [8,20,24] | |

| Policies | Access to resources | Ownership of gathering sites by farmers themselves; exceptional permits for gathering widely distributed protected plant species | Obtaining gathering permits from public and private landowners is laborious; prohibition of gathering protected species and gathering in protected areas | Obtaining continuous permission to access gathering locations for wild plant harvesting can be limiting; policies regulating access differ greatly between and within countries [3,25,26,27] |

| Food safety regulations | n/a | Obligatory course at professional school required; prohibition of medicinal plant gathering; | Food safety policies regulating the sale of wild plants and the training needed for sellers limit commercialisation [28] | |

| Support measures | Obligatory course at regional professional school provides training | n/a | Political support measures to enhance wild plant commercialisation are on the edge of political sectors and difficult to access for entrepreneurs; individual countries provide training, subsidies or tax exemptions [1,2,17,29,30,31] | |

| Socio-economic | Income | Increase in product quantity and quality through wild plant gathering increases income | n/a | Prospect of income may be a decisive factor for engaging in wild plant commercialisation, although for some gatherers idealistic reasons prevail [7,8,29,32] |

| Labour | No work investment needed for cultivating and tending many wild plant species | Natural fostering is time consuming but needed for several wild plant species; need for several gatherers at particular times | Availability of labour is an important precondition for wild plant commercialisation [11,16,17,29,33] | |

| Market | Competition | Wild plant species have unique product qualities and tastes compared to cultivated plant species; cultivation of some plant species difficult | Cultivation of some plant species easy; increasing competition because several producers offer similar products | Commercialisation of gathered wild plant species may compete with the commercialisation of cultivated plants of the same or similar species; competition may also occur between different kinds of value chains [8,14,34,35] |

| Value chain type | Availability of direct marketing structures | n/a | Availability of value chains for large-scale gathering and direct marketing structures for farming families support wild plant commercialisation [7,8,36,37] | |

| Demand | Rising demand for wild plant products; trend for healthy and regional foods; increasing opportunities to learn about wild plant uses | n/a | Trend for wild plant products supports wild plant commercialisation, while such trends may appear and vanish quickly [8,15,27,37,38,39,40,41] | |

| Certification and labelling | Certification enhances trust in environmental sustainability of production processes and food safety; societal trend for certification | Certification needs bureaucratic efforts; lack of consumer awareness about additional value of organic certification; cases of fraud in organic market damage trust in organic label | Certification can improve market access and income for producers, enhance sustainability and offer better traceable value chains for consumers but may be challenging to achieve due to certification processes and requirements [27,42] | |

| Culture | Traditional and local knowledge | Traditions for wild plant gathering available; opportunities for knowledge transmission and learning available; | n/a | Wild plant commercialisation is frequently rooted in cultural practices and related knowledge, which may support or limit wild plant commercialisation [6,17,18,30,38,43,44] |

| Attitudes | appreciation of health benefits of wild plant species; appreciation of being outdoors and connected with nature when gathering | n/a | Perception among gatherers of wild plant gathering being a pleasurable activity and enhancing connectedness to nature may support wild plant commercialisation [6,9,24,33] | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schunko, C.; Lechthaler, S.; Vogl, C.R. Conceptualising the Factors that Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072028

Schunko C, Lechthaler S, Vogl CR. Conceptualising the Factors that Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy). Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072028

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchunko, Christoph, Sarah Lechthaler, and Christian R. Vogl. 2019. "Conceptualising the Factors that Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy)" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072028

APA StyleSchunko, C., Lechthaler, S., & Vogl, C. R. (2019). Conceptualising the Factors that Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy). Sustainability, 11(7), 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072028