Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Stakeholder Analysis of Sustainable Architectural Heritage Development

3. Research Methodologies

3.1. Primary Selection of Stakeholders

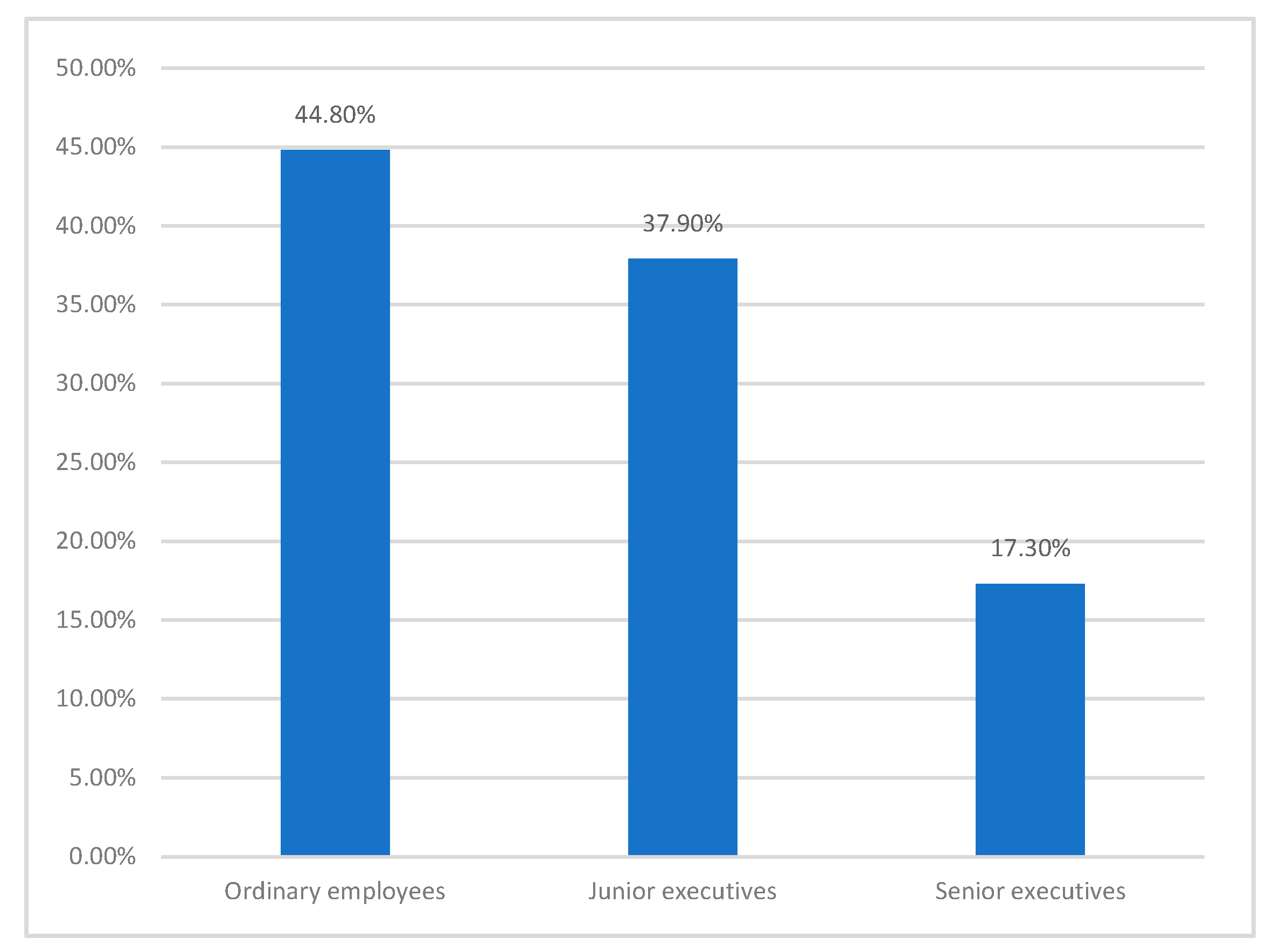

3.2. Assessing the Importance and Enthusiasm of All Selected Stakeholders

3.3. Data Process and Validation

3.4. Results, Discussions, and Extraction of Implications from the Results

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Importance of the Stakeholders in the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage

4.2. Enthusiasm of the Stakeholders on the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage

4.3. Critical Stakeholders Analysis

5. Implications

5.1. Consolidate the Importance and Participating Enthusiasm of Critical Stakeholders

5.2. Enhance the Participation of the Public

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giannakopoulou, S.; Kaliampakos, D. The social aspects of rural, mountainous built environment. Key elements of a regional policy planning. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Cultua; Prentice-Hall of India Private Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Charter of the Architectural Heritage; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bakri, A.F.; Ibrahim, N.; Ahmad, S.S.; Zaman, N.Q. Valuing built cultural heritage in a Malaysian urban context. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço-Gomes, L.; Pinto, L.M.C.; Rebelo, J.F. Visitors’ preferences for preserving the attributes of a world heritage site. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.G. Urban authenticity at stake: A new framework for its definition from the perspective of heritage at the Shanghai Music Valley. Cities 2017, 70, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. International influence and local response: Understanding community involvement in urban heritage conservation in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. Preservation, conservation and heritage: Approaches to the past in the present through the built environment. Asian Anthropol. 2011, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H. Governance of built-heritage in a restrictive political system: The involvement of non-governmental stakeholders. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najd, M.D.; Ismail, N.A.; Maulan, S.; Yunos, M.Y.M.; Niya, M.D. Visual preference dimensions of historic urban areas: The determinants for urban heritage conservation. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, P.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijgrok, E.C. The three economic values of cultural heritage: A case study in the Netherlands. J. Cult. Herit. 2006, 7, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioni, F.; Lenzerini, F. The 1972 World Heritage Convention: A Commentary; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embaby, M.E. Heritage conservation and architectural education: “An educational methodology for design studios”. HBRC J. 2014, 10, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L. Urban conservation policy and the preservation of historical and cultural heritage: The case of Singapore. Cities 1996, 13, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg-Webster, S.; Kinahan, K.L. Historic preservation and urban revitalization in the twenty-first century. J. Plan. Lit. 2014, 29, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, M. A synopsis of the laws protecting our cultural heritage. New Eng. L. Rev. 1993, 28, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G. China’s architectural heritage conservation movement. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modena, C.; da Porto, F.; Valluzzi, M.R.; Munari, M. Criteria and technologies for the structural repair and strengthening of architectural heritage. In Proceedings of the Rehabilitation and Restoration of Structures, At Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, Chennai, India, 13–16 February 2013; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Regional aspects of heritage economics: Analytical and policy issues. Australas. J. Reg. Stud. 2007, 13, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mecocci, A.; Abrardo, A. Monitoring Architectural Heritage by Wireless Sensors Networks: San Gimignano—A Case Study. Sensors 2014, 14, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Avrami, E. Heritage values and challenges of conservation planning. In Management Planning for Archaeological Sites; Teutonico, J.M., Palumbo, G., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.; Smith, S.; Shaer, M. A Didactic Case Study of Jarash Archaeological Site. Jordan: Stakeholders and Heritage Values in Site Management, Los Angeles-Amman; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaikaew, K. The Cultural Tourism Management under Context of World Heritage Sites: Stakeholders’ Opinions between Luang Prabang Communities, Laos and Muang-kao Communities, Sukhothai, Thailand. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1286–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Douvere, F. The engagement of stakeholders in the marine spatial planning process. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M.M.; Hallo, J.C.; Backman, S.J.; Norman, W.C.; Vogel, M.A. Value orientations and heritage tourism management at Petra Archaeological Park, Jordan. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.; Ahmad, C.B.; Jaafar, J.; Sa’ad, S.R.M. Stakeholders’ Perspectives of Criteria for Delineation of Buffer Zone at Conservation Reserve: FRIM Heritage Site. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S. Stakeholders and community participation. In Managing World Heritage Sites; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2006; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T.H. Value of augmented reality at cultural heritage sites: A stakeholder approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, F.; Eden, C. Strategic management of stakeholders: Theory and practice. Long Range Plan. 2011, 44, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Student and teacher views about technology: A tale of two cities? J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2007, 39, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.L.; Miles, S. Developing stakeholder theory. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C. What stakeholder theory is not. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.T. Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Lawrence, A.T.; Weber, J.; SJ, J.W. Business and Society: Corporate Strategy, Public Policy, Ethics; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.; Sillanpää, M. The Stakeholder Corporation: A Blueprint for Maximizing Stakeholder Value; Pitman Publishing: Pitman, London, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, J.; Robson, I. From shareholders to stakeholders: Critical issues for tourism marketers. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Gandino, E. Co-designing the solution space for rural regeneration in a new World Heritage site: A Choice Experiments approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bramwell, B. Heritage protection and tourism development priorities in Hangzhou, China: A political economy and governance perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksić, M.; Dobričić, M.; Trkulja, S. Institutional limitations in the management of UNESCO cultural heritage in Serbia: The case of Gamzigrad-Romuliana archaeological site. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Living in a World Heritage City: Stakeholders in the dialectic of the universal and particular. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nana Ato Arthur, S.; Victor Mensah, J. Urban management and heritage tourism for sustainable development: The case of Elmina Cultural Heritage and Management Programme in Ghana. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2006, 17, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günlü, E.; Pırnar, I.; Yağcı, K. Preserving cultural heritage and possible impacts on regional development: Case of İzmir. Int. J. Emerg. Transit. Econ. 2009, 2, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lask, T.; Herold, S. An observation station for culture and tourism in Vietnam: A forum for World Heritage and public participation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2004, 7, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M. The socio-economic impact of built heritage projects conducted by private investors. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroumand, H.; Zain, M.F.M.; Jamil, M. A guideline for assessing of critical parameters on Earth architecture and Earth buildings as a sustainable architecture in various countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 130–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Shen, L.; Shuai, C.; He, B. A novel approach for assessing the performance of sustainable urbanization based on structural equation modeling: A China case study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andy, F. Discovering statistics using spss for windows: Advanced techniques for the beginner; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J.; Howell, D.C.; Garthwaite, P.H. Payne and Jones revisited: Estimating the abnormality of test score differences using a modified paired samples t test. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998, 20, 898–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardinha, I.D.; Reijnders, L.; Antunes, P. Using corporate social responsibility benchmarking framework to identify and assess corporate social responsibility trends of real estate companies owning and developing shopping centres. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders | Responsibilities | Interests Demands | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central government | Establishing the policies and specifications and supervising the implementation | A sustainable development of architectural heritage | [47,48] |

| Local government | Implementing the policies of architectural heritage protection within its administrative division | A sustainable development of architectural heritage within its administrative division | [9,25] |

| Tourism management departments | Checking the operation of architectural heritage | A favorable traveling environment including a maximum investment return | [42] |

| Community resident committees | Communicating the protection plan to residents and coordinating the relationship between residents and administration of architectural heritage | Reducing the adverse impact of architectural heritage protection on the community residents | [44] |

| Real Estate development enterprise | Investing and organizing the project of architectural heritage protection under the authority of local government and administrations | Obtaining economic benefits and enhancing the popularity of company | [25] |

| Administration of architectural heritage protection | Using, managing, and maintaining the architectural heritage | The normal operation and maintenance of architectural heritage | [45,46] |

| Local residents | Participating in the protection of architectural heritage and understanding the policy in the architectural heritage protection | Obtaining an increase of income and an improvement of life quality from the protection of architectural heritage | [43] |

| Travel agencies | Ensuring the fair use of architectural heritage and the less damage of architectural heritage from tourists | Obtaining better tourism resource from the protection of architectural heritage | [49,50] |

| Tourism investment company | Investing for the architectural heritage protection | Obtaining maximum profits and the sustainable development of company | [44] |

| Expert group | Providing intellectual support for the protection of architectural heritage | Obtaining theoretical achievements from the experience of architectural heritage protection | [30] |

| Media | Reporting and disseminating information about architectural heritage protection | An objective report and evaluation of the situation in architectural heritage protection | [4,9] |

| Construction company of architectural heritage protection | Completing the project of architectural heritage protection according to the requirements of quality and time | Gaining construction profit from the project of architectural heritage protection | [44] |

| Tourists | Providing feedback and suggestion for the architectural heritage protection | Obtaining better travel experience from the architectural heritage | [1,51] |

| Index | Importance | Enthusiasm |

|---|---|---|

| α coefficient | 0.895 | 0.873 |

| KMO | 0.873 | 0.872 |

| No. | Stakeholders | Sample Capacity | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Central government | 317 | 4.32 | 0.74 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | Local government | 317 | 4.37 | 0.79 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | Tourism management department | 317 | 3.21 | 1.01 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | Community resident committee | 317 | 2.97 | 1.40 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | Real estate development enterprise | 317 | 4.35 | 0.73 | 3 | 5 |

| 6 | Construction company of architectural heritage protection | 317 | 3.57 | 1.29 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | Travel agency | 317 | 1.68 | 0.77 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | Tourism investment company | 317 | 3.13 | 1.04 | 1 | 5 |

| 9 | Expert group | 317 | 4.05 | 0.99 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 | Local residents | 317 | 4.19 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | Tourists | 317 | 3.35 | 1.32 | 1 | 5 |

| 12 | Media | 317 | 2.40 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 |

| 13 | Administration of architectural heritage protection | 317 | 3.77 | 0.99 | 1 | 5 |

| NO. | Stakeholders | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tourism management department | 2.5% | 24.0% | 34.7% | 27.4% | 11.4% |

| 2 | Community resident committee | 19.6% | 21.1% | 21.1% | 18.6% | 19.6% |

| 3 | Construction company of architectural heritage protection | 9.8% | 11.7% | 19.6% | 29.7% | 29.3% |

| 4 | Tourism investment company | 8.8% | 14.5% | 39.4% | 29.7% | 7.6% |

| 5 | Tourists | 12.3% | 14.5% | 23.0% | 26.5% | 23.7% |

| 6 | Media | 21.5% | 39.7% | 22.4% | 10.1% | 6.3% |

| CG | LG | TMD | CRC | REDE | CCAHP | TA | TIC | EG | LR | TU | ME | AAHP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | - | −0.05 (−0.84) | 1.11 ** (17.78) | 1.34 ** (15.99) | −0.03 (−0.52) | 0.75 ** (9.43) | 2.64 ** (41.02) | 1.19 ** (15.99) | 0.26 ** (3.77) | 0.13 * (2.13) | 0.97 ** (11.15) | 1.92 ** (25.38) | 0.55 ** (7.81) |

| LG | - | 1.15 ** (15.91) | 1.39 ** (15.46) | 0.02 (0.32) | 0.79 ** (9.69) | 2.69 ** (42.74) | 1.24 ** (17.69) | 0.31 ** (4.33) | 0.18 ** (3.08) | 1.02 ** (12.39) | 1.97 ** (25.64) | 0.59 ** (8.29) | |

| TMD | - | 0.24 * (2.45) | −1.14 ** (−17.15) | −0.36 ** (−3.92) | 1.53 ** (21.72) | 0.09 * (1.09) | −0.84 ** (−10.07) | −0.97 ** (−13.06) | −0.14 * (−1.40) | 0.81 ** (9.57) | −0.56 ** (−6.80) | ||

| CRC | - | −1.37 ** (−15.88) | −0.60 ** (−5.69) | 1.30 ** (14.06) | −0.15 * (−1.56) | −1.08 ** (−11.13) | −1.21 ** (−14.09) | −0.37 ** (−3.40) | 0.57 ** (5.86) | −0.80 ** (−8.42) | |||

| REDE | - | 0.78 ** (9.36) | 2.67 ** (43.55) | 1.22 ** (17.13) | 0.29 ** (4.20) | 0.16 * (2.74) | 1.00 ** (11.39) | 1.95 ** (25.85) | 0.57 ** (8.07) | ||||

| CCAHP | - | 1.89 ** (22.64) | 0.44 ** (4.97) | −0.48 ** (−5.21) | −0.62 ** (−7.35) | 0.22 * (2.27) | 1.17 ** (12.85) | −0.20 * (−2.11) | |||||

| TA | - | −1.45 ** (−23.88) | −2.38 ** (−33.68) | −2.51 ** (−40.44) | −1.67 ** (−19.99) | −0.72 ** (−10.11) | −2.09 ** (−27.74) | ||||||

| TIC | - | −0.93 ** (−12.05) | −1.06 ** (−16.73) | −0.22 * (−2.67) | 0.73 ** (9.21) | −0.65 ** (−8.05) | |||||||

| EG | - | −0.13 (−1.83) | 0.71 ** (8.19) | 1.65 ** (20.15) | 0.28 ** (4.92) | ||||||||

| LR | - | 0.84 ** (10.36) | 1.79 ** (22.18) | 0.41 ** (5.82) | |||||||||

| TU | - | 0.95 ** (10.55) | −0.43 ** (−4.80) | ||||||||||

| ME | - | −1.37 ** (−17.17) | |||||||||||

| AAHP | - |

| NO. | Stakeholders | Sample Capacity | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Central government | 317 | 4.49 | 0.67 | 3 | 5 |

| 2 | Local government | 317 | 4.40 | 0.65 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | Tourism management department | 317 | 3.22 | 0.99 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | Community resident committee | 317 | 2.86 | 1.33 | 1 | 5 |

| 5 | Real estate development enterprise | 317 | 3.67 | 1.20 | 1 | 5 |

| 6 | Construction company of architectural heritage protection | 317 | 3.80 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | Travel agency | 317 | 2.12 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 |

| 8 | Tourism investment company | 317 | 4.02 | 1.13 | 1 | 5 |

| 9 | Expert group | 317 | 4.31 | 0.90 | 1 | 5 |

| 10 | Local residents | 317 | 3.39 | 1.17 | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | Tourists | 317 | 3.32 | 1.24 | 1 | 5 |

| 12 | Media | 317 | 2.28 | 1.06 | 1 | 5 |

| 13 | Administration of architectural heritage protection | 317 | 4.13 | 0.93 | 1 | 5 |

| NO. | Stakeholders | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community residents committee | 19.9% | 22.4% | 23.0% | 20.8% | 13.9% |

| 2 | Real estate development enterprise | 8.2% | 7.9% | 21.5% | 34.1% | 28.4% |

| 3 | Construction company of architectural heritage protection | 2.2% | 11.7% | 21.8% | 33.1% | 31.2% |

| 4 | Travel agency | 31.2% | 42.0% | 14.5% | 7.3% | 5.0% |

| 5 | Tourism investment company | 4.1% | 5.4% | 22.4% | 21.1% | 47.0% |

| 6 | Local residents | 6.6% | 18.3% | 21.8% | 35.6% | 17.7% |

| 7 | Tourists | 8.5% | 18.3% | 27.4% | 24.0% | 21.8% |

| 8 | Media | 25.2% | 39.1% | 21.8% | 10.4% | 3.5% |

| CG | LG | TMD | CRC | REDE | CCAHP | TA | TIC | EG | LR | TU | ME | AAHP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG | - | 0.09 (1.58) | 1.26 ** (21.01) | 1.62 ** (19.76) | 0.82 ** (11.27) | 0.69 ** (10.20) | 2.36 ** (32.81) | 0.47 ** (6.37) | 0.18 * (2.80) | 1.09 ** (14.81) | 1.16 ** (14.50) | 2.21 ** (32.72) | 0.36 ** (5.57) |

| LG | - | 1.18 ** (16.79) | 1.54 ** (17.89) | 0.74 ** (9.82) | 0.61 ** (8.44) | 2.27 ** (30.20) | 0.38 ** (5.11) | 0.09 (1.29) | 1.01 ** (12.36) | 1.08 ** (13.57) | 2.12 ** (28.80) | 0.27 ** (3.89) | |

| TMD | - | 0.36 ** (3.92) | −0.44 ** (−5.31) | −0.57 ** (−7.00) | 1.09 ** (13.99) | −0.79 ** (−9.67) | −1.09 ** (−13.88) | −0.17 * (−2.02) | −0.10 (−1.07) | 0.95 ** (11.97) | −0.91 ** (−11.32) | ||

| CRC | - | −0.80 ** (1.58) | −0.93 ** (−9.97) | 0.74 ** (7.55) | −1.15 ** (−11.92) | −1.44 ** (−15.79) | −0.53 ** (−5.42) | −0.46 ** (−4.56) | 0.59 ** (6.21) | −1.26 ** (−14.23) | |||

| REDE | - | −0.13 (−1.58) | 1.54 ** (17.10) | −0.35 ** (−3.87) | −0.64 ** (−7.50) | 0.27 ** (2.87) | 0.34 ** (3.62) | 1.39 ** (15.16) | −0.46 ** (−5.70) | ||||

| CCAHP | - | 1.67 ** (19.80) | −0.22 * (−2.64) | −0.51 ** (−6.52) | 0.40 ** (4.63) | 0.47 ** (5.10) | 1.52 ** (18.21) | −0.33 ** (−4.12) | |||||

| TA | - | −1.89 ** (−21.49) | −2.18 ** (−28.29) | −1.26 ** (−13.85) | −1.19 ** (−13.04) | −0.15 (−1.77) | −2.00 ** (−23.82) | ||||||

| TIC | - | −0.29 ** (−3.58) | 0.62 ** (7.03) | 0.69 ** (7.20) | 1.74 ** (20.83) | −0.11 (−1.35) | |||||||

| EG | - | 0.91 ** (10.95) | 0.99 ** (11.75) | 2.03 ** (26.89) | 0.18 * (2.64) | ||||||||

| LR | - | 0.07 (0.84) | 1.12 ** (12.67) | −0.74 ** (−9.02) | |||||||||

| TU | - | 1.04 ** (11.96) | −0.81 ** (−9.12) | ||||||||||

| ME | - | −1.85 ** (−23.69) | |||||||||||

| AAHP | - |

| Categories | Standard | Critical Point | Scope | Stakeholders | Level of Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | + | 4.31 | ≥4.31 | LG, REDE, CG | Very important |

| II | 3.49 | 3.49–4.31 | LR, EG, AAHP, CCAHP | Important | |

| III | 2.67 | 2.67–3.49 | TU, TMD, TIC, CRC | Unimportant | |

| IV | ≤2.67 | ME, TA | Very unimportant |

| Categories | Standard | Critical Point | Scope | Stakeholders | Level of Enthusiasm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | + | 4.31 | ≥4.31 | CG, LG, EG | Very active |

| II | 3.54 | 3.54–4.31 | AAHP, TIC, CCAHP, REDE | Active | |

| III | 2.77 | 2.77–3.54 | LR, TU, TMD, CRC | Inactive | |

| IV | ≤2.77 | ME, TA | Very inactive |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J. Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671

Wang R, Liu G, Zhou J, Wang J. Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China. Sustainability. 2019; 11(6):1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruiling, Guo Liu, Jingyang Zhou, and Jianhui Wang. 2019. "Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China" Sustainability 11, no. 6: 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671

APA StyleWang, R., Liu, G., Zhou, J., & Wang, J. (2019). Identifying the Critical Stakeholders for the Sustainable Development of Architectural Heritage of Tourism: From the Perspective of China. Sustainability, 11(6), 1671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061671