1. Introduction

Between agro-food products, coffee is the first commodity to quarrel in ethical attributes and sustainability issues such as fair trade, premium prices, as well as justified value chain issues [

1,

2,

3]. Several consumer culture specialists mention that the phenomenon is part of “third wave coffee” where coffee is not only a commodity with a strong cultural character but also a worldwide global business [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Now, the development of the coffee consumption trend is fast and dynamic; several consumer culture observers are even building a “fourth wave” theory [

8,

9]. In the fourth wave theories, global coffee consumption will lead to a coffee consumption model with the best quality becoming a popular trend as well as an extended business to build a new supply chain that is different from the current condition [

8,

9]. Coffee has shifted from a business involving the control of traditional means of production such as land, capital, and technology to control over the means of symbolic production in extracting a surplus value through global trade [

4,

10].

Specialty coffee becomes one of the alternatives to liberate the producer from the unjustified coffee market structure [

9,

11,

12]. Single origin coffee is the next most realistic strategy to give protection to the uniqueness of environment where coffee are producing as well as its cultural characteristics of the coffee farmer societies [

2,

13]. Geographical indication becomes one of the strategies not only to serve the origin-tracked issue but also to protect the uniqueness of coffee and its culture [

12,

13]. Despite a small market share, since the early 2000s until now, the existence of the single origin coffee market has given the alternative and new perspective that coffee obtains premium prices and has slowly changed the coffee consumption globally [

11,

14,

15].

Many kinds of research on coffee mainly look at the themes of lifestyle or the social place of millennials [

16], consumer loyalty and branding [

17], culture and locality [

18,

19,

20], and political movement [

19]. Several kinds of research concerning coffee consumption are focusing very often on the ethics and sustainability issues [

20,

21], while issues related to the evolution of the institutional coffee business at the local level does not get enough attention. In the economic aspect, there is very often information, especially for the supply chain aspect, on the impact of the development of new coffee business networks on the farmers’ welfare, including the role of the farmer group and cooperative [

20,

22,

23,

24]. At the same time, many researches on coffee consumption focus on the personal preferences related to taste [

25] and other motives where institutional aspects of the economy, especially related to SOCSs business, are relatively rare to be discussed.

Observing the developing consumption growth throughout the year, the coffee business is still considered an interesting and profitable business because it is a dynamic business in facing consumer culture development, including technology [

10,

26]. The consumption of coffee is expected to increase by 0.06 million bags from 3.09 million bags in 2016 to 3.15 million bags of green bean equivalent (GBE) in 2017 [

27]. According to the Canada–Indonesia Trade and Private Sector Assistance (TPSA), the per capita coffee consumption in Indonesia has increased from 0.5 kilograms per year in 2000 to 1.1 kilograms in 2016 due to an increasing middle-class population [

28]. At the same time, the production of Indonesian-Arabica coffee is also seen rising slightly to 1.4 million bags from 1.2 million bags in 2017 according to the Canada–Indonesia Trade and Private Sector Assistance (TPSA) project [

29].

Additionally, several lifestyle changes, such as urbanization, that have had a positive impact on domestic coffee consumption changing coffee shop strategies tend to focus on high-quality specialty coffees [

26,

30]. The demand for high-quality specialty coffees is a new lifestyle in urban areas due to the growing enthusiasm that has a special interest in the items they consume, often referred to as connoiseurs, including of coffee. Thus, this article focuses on the effort of acknowledging how connoisseur consumers moderate the shop managers to build their dynamics capabilities to draw clearer sustainability consumption on the coffee mechanism. This is in line with the fourth wave of coffee where a single origin or country of origin becomes an important issue along with a better coffee seed quality in the market [

9]. Locality as the cultural setting also heavily affects the consumers’ behavior in the coffee business [

25] environment marked by raises the dynamic of the coffee shop business in developing countries that are starting to build single origin coffee as a new commodity in the coffee market [

12].

Along with the development of the coffee business, coffee lovers have also emerged as a new consumer group that regards coffee as not only consumption items but also part of a culture [

5,

31,

32]. The frontman of these groups not only enjoys coffee but also builds a new coffee culture, such as encouraging fair trade processes, promoting environmental care, and other various cultural movements including political resistance [

4,

21,

33]. This group is known as connoiseurs, and its existence is vital in the development of the coffee industry. Thus, it is important to study the dynamic of this “coffee house” business at the local level, especially its sustainability consumption, connoisseurs’ role, and the strategy of the managers in winning the competition.

2. Theoretical Frameworks

Connoisseur consumers (CCs) are consumers that pay more attention to the goods they buy [

31,

32,

33], such as the origin of the goods, the quality, the friendliness on the environment, and other ethnical attributes [

33,

34,

35]. Theoretically, their behavior is relatively sustainable because they pay specific attention to the environmental issues as well as have the willingness to pay for environmentally friendly products more than general consumers [

3,

36,

37]. They have the tendency to try understanding, evaluating, and appreciating the consumption of objects, subjectively showing a preference towards certain coffee attributes such as the origin of the coffee, the serving method, and others [

9,

38]. Connoisseurs enjoy more of the behavior as a leisure activity as well as emphasizes the different self-identities with many of the consumers group where its characteristics are empathy to the environment, not having a problem with the price, and subjectively caring about the goods and service they consume [

9,

39,

40,

41]. Because of the various attributes, these CCs have the potential to build their own subculture that is different from regular consumers [

35,

39,

42].

They are not the only important visitors; CCs also have the ability to build a community and to generate a new subculture and social capital that can support the existence of SOCSs. Even a small existence of CCs has the potential to build specific consumer communities between not only their own but also consumers in general. Thus, the existence of CCs will be able to help single origin coffee shops to build a community of consumers so that they will rely not only on the impulse consumers but also on special consumers driven by CCs. Based on the above description, this article specifically analyzes whether the existence of connoisseur consumers between the consumers of single origin coffee shops will be able to improve the dynamics capabilities of SOCSs and to build the sustainability consumption of single origin coffee.

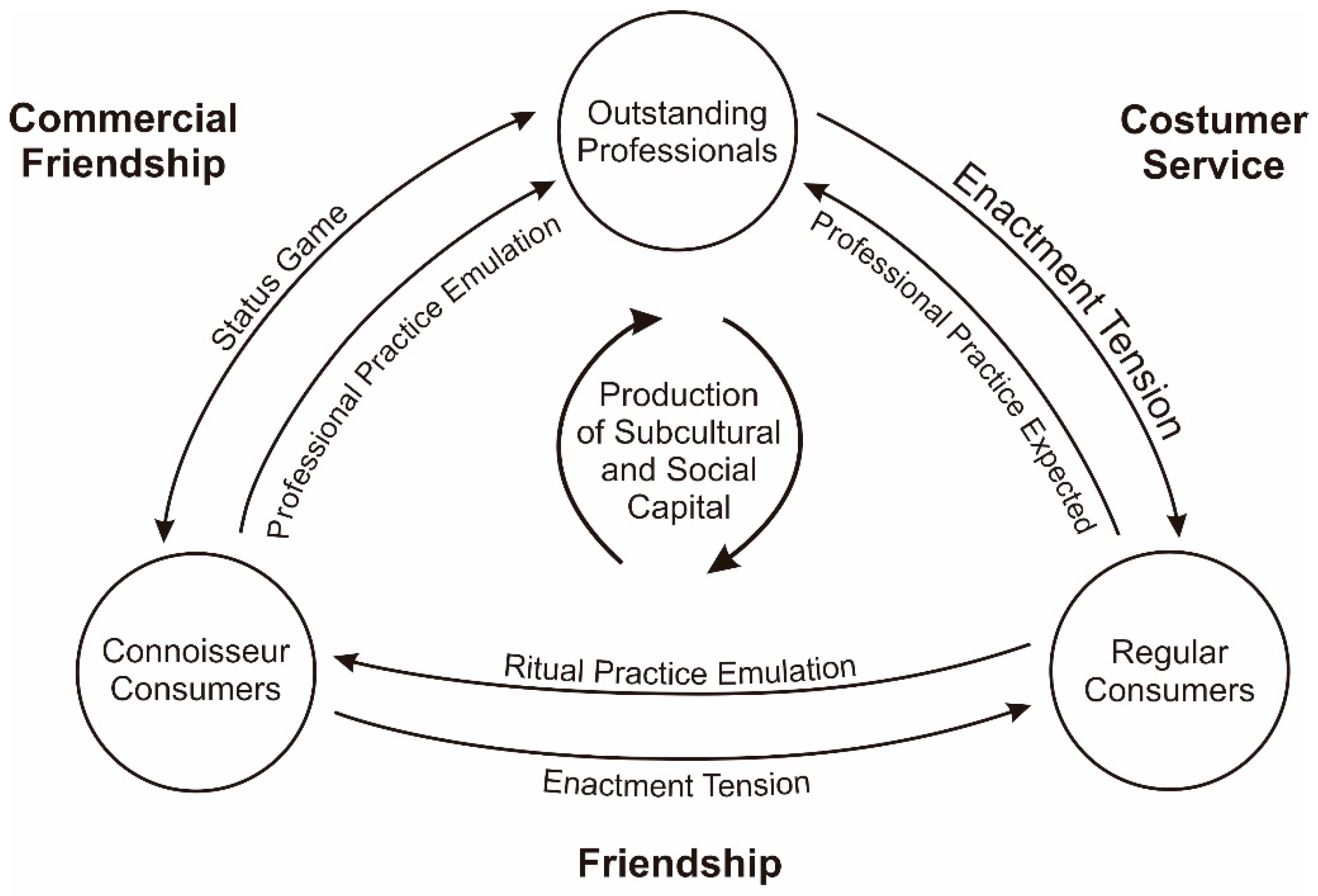

Figure 1 shows that CCs can attract other consumers, both regular or general visitors, and outstanding professionals to build social capital and a new subculture [

32,

35,

39].

On the dynamic capabilities side, the existence of CCs as the market segment is relatively more loyal with a clearer preference than regular consumers; its potential facilitates the company in sensing, seizing, and transforming the company to be more directed relatively. For example, the huge existence of CCs in the consumers’ structure in a company facilitates the managers in detecting what knowledge will likely be asked by them. The company can also anticipate it by giving enough education to its personnel who will communicate with the CCs. Therefore, the existence of CCs will facilitate the company to detect what are the required needs to serve the typology of such consumers. The analysis ability on the external demand to skillfully change the organization to answer those challenges is one of the signs that a company has good DCs [

43].

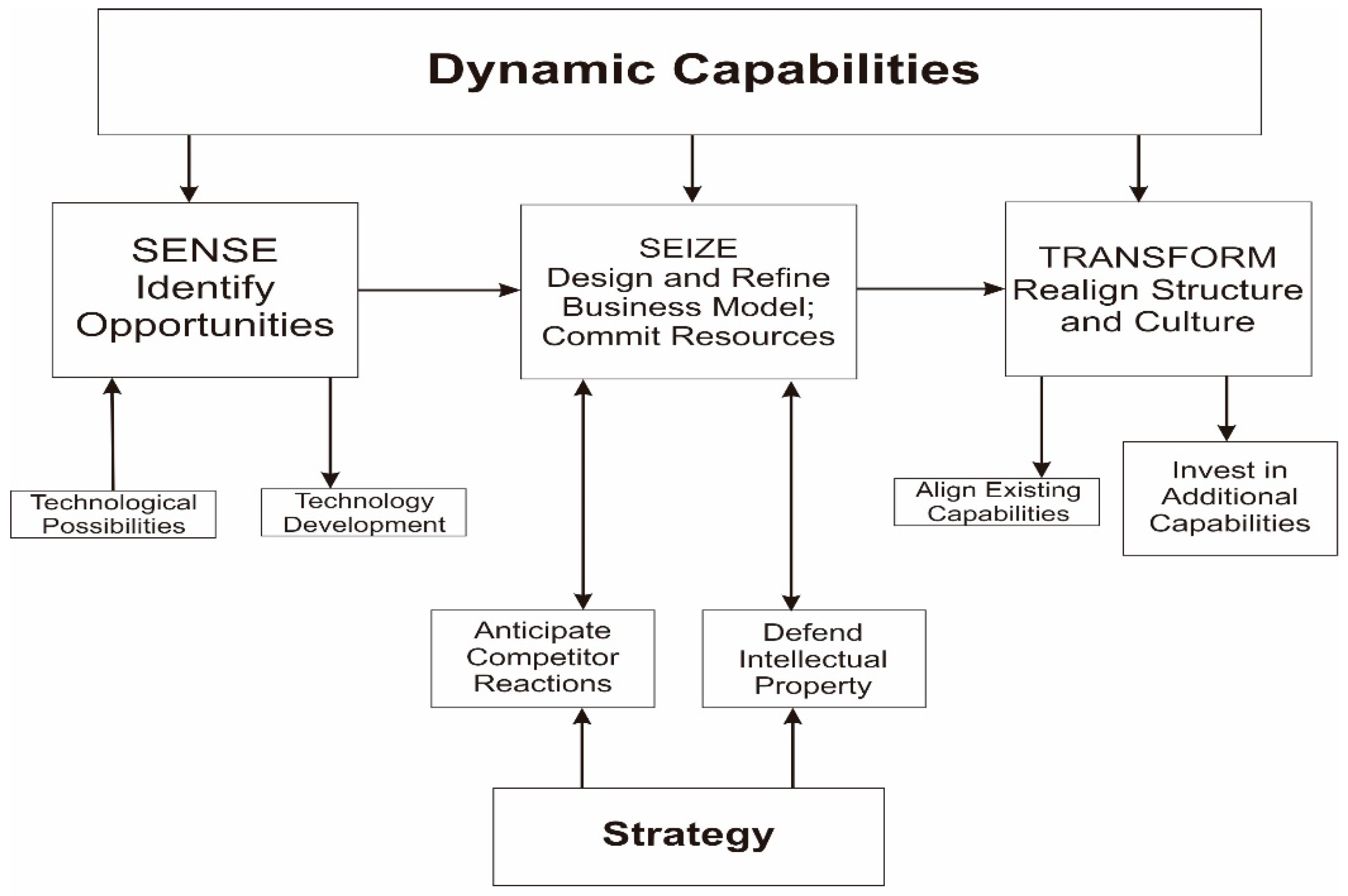

Dynamics capabilities (DCs) is a theory emerging to answer why many business institutions that have dominated the asset, have a strong human resources, and have a solid system but will collapse in facing the competition, while others have the ability to survive and even develop rapidly. According to the initiator, dynamics capabilities count not only the corporate mastery of assets and human resources but also the ability of the institution itself to sense, seize, and actively transform the value and management of the organization to be responsive toward change and competition [

44,

45,

46,

47]. It is indigenous in nature and owned by a company so that it is impossible to be imitated by other companies because DCs involve “distinct skills, processes, procedures, organizational structures, decision rules, and disciplines.” [

43,

47,

48,

49]. Moreover, it will be easier for the company to choose the most effective strategy to win the competition because the manager can improve quickly their business model [

44,

45,

49,

50,

51]. A business model that is capable to utilize the mapped resources in accordance with the needs of consumers will have strong dynamic capabilities [

44,

50,

51].

On the seizing side of DC concepts, the management builds two strategies, namely anticipating the competitor’s reaction that can disturb the sustainability of the company and using the intellectual property to maintain dominance [

44,

49]. This intellectual property is an asset from the company that is impossible to be imitated by other companies due to the rights claim attached to that company [

43] so the company has the monopoly. In the SOCSs context, our hypothesis is this intellectual property can be in the form of concept development of the shop; other than the difficulty to be imitated due to its originality, shame will be one of the barriers for imitating the process. Meanwhile, in anticipating the reaction from the competitor, especially for a traditional coffee shop, the specific strategy can be used to anticipate the price and promotion, or additional facilities provision can also be an option [

22,

35,

52]. This strategy is one of the ways for the manager in designing and refining business model to be able to seize more effectively.

Meanwhile, in transforming the company periodically so that the structure and its culture will be more responsive to changes, the manager should do an alliance process and investment to improve the company’s capability [

53,

54,

55]. The ability to always build a flexible value and to move all parties is very important for the company in order to adjust to practical community needs [

43]. For example, the partnership with a “sharing” principle between Uber and personal car owners means sharing the risk and resources so that the company becomes more competitive [

43,

55]. At the same time, the company will be able to invest more carefully, and it will have a big impact on improving their dynamics capabilities [

43,

48,

56]. This following

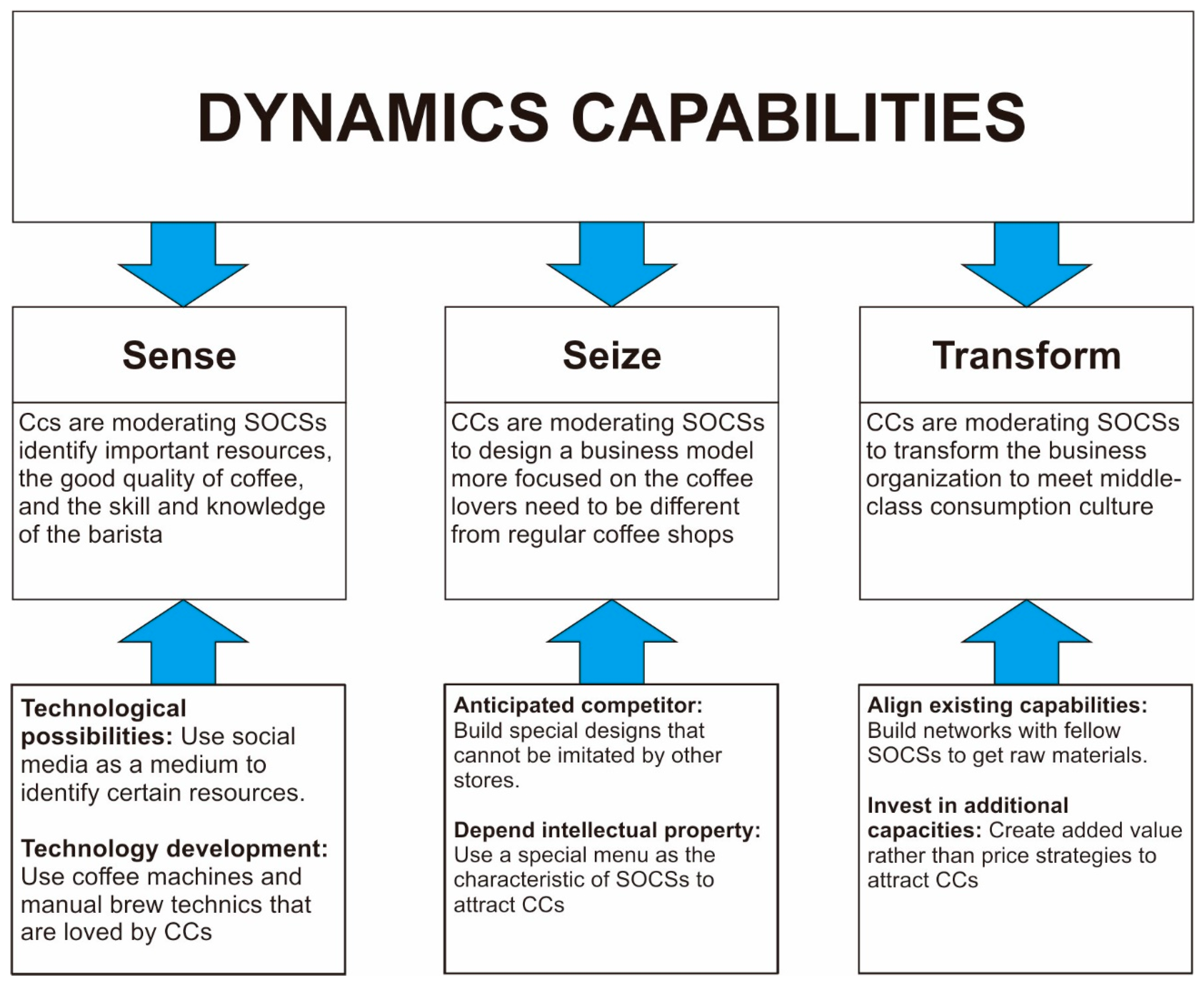

Figure 2 shows the scheme of how the DCs of a business organization is built, thus making them able to compete with competitors.

What is the relationship between sustainability and dynamics capabilities? Referring to several views, sustainability is a measure to analyze whether an economic, ecological, and social aspect is able to grow and develop jointly without being defeated by one and another [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. There is a balance between socioeconomic and environmental sustainability, not only for human existence but also the existence of civilization and environment. On the economic aspect, based on the definition by References [

62,

64] that stated, “sustainable consumption behavior [is] individual acts of satisfying needs in different areas of life by acquiring, using, and disposing goods and services that do not compromise the ecological and socioeconomic conditions of all people (currently living or in the future) to satisfy their own needs.” Furthermore, in accordance with the work done by References [

62,

64,

65], consumption on the service and goods will not only compromise with ecological and socioeconomic conditions for the sustainability of the next generation.

Furthermore, Reference [

61] centralized the ways to analyze sustainable consumption by involving three main dimensions, namely the dimensions of sustainability, consumption phase, and consumption area, and one specific indicator, namely the impact as a result of consumption. The sustainability dimension includes ecological and social economic sustainability, while the consumption phase involves the acquisition, usage, and disposal and the consumption area involves food, housing, mobility, clothing, and others. Meanwhile, the impact indicator as the follower from the consumption activity is seen from both the good and bad sides by a certain degree. Furthermore, in this article, sustainability can also be seen on two sides, namely SOCSs as a business institution and CCs as active consumers.

On the institutional business, sustainability can be verified from the efforts by the company, starting from the effort in transferring knowledge to the customers [

64,

66], in efficient energy consumption [

58,

67], in transparent business processes [

58], and in the reduction of production waste [

67]. Those four contributions depicted from this research can be seen from three main activities from the coffee business, namely the production and consumption processes [

58], as well as marketing [

68], where the existence of CCs “force” the shop to do activities in encouraging coffee business processes to be more sustainable. How much the CCs contribute in encouraging the company to transform into more sustainable and how the consumers’ behaviors keep the sustainable values will be analyzed.

3. Materials and Methods

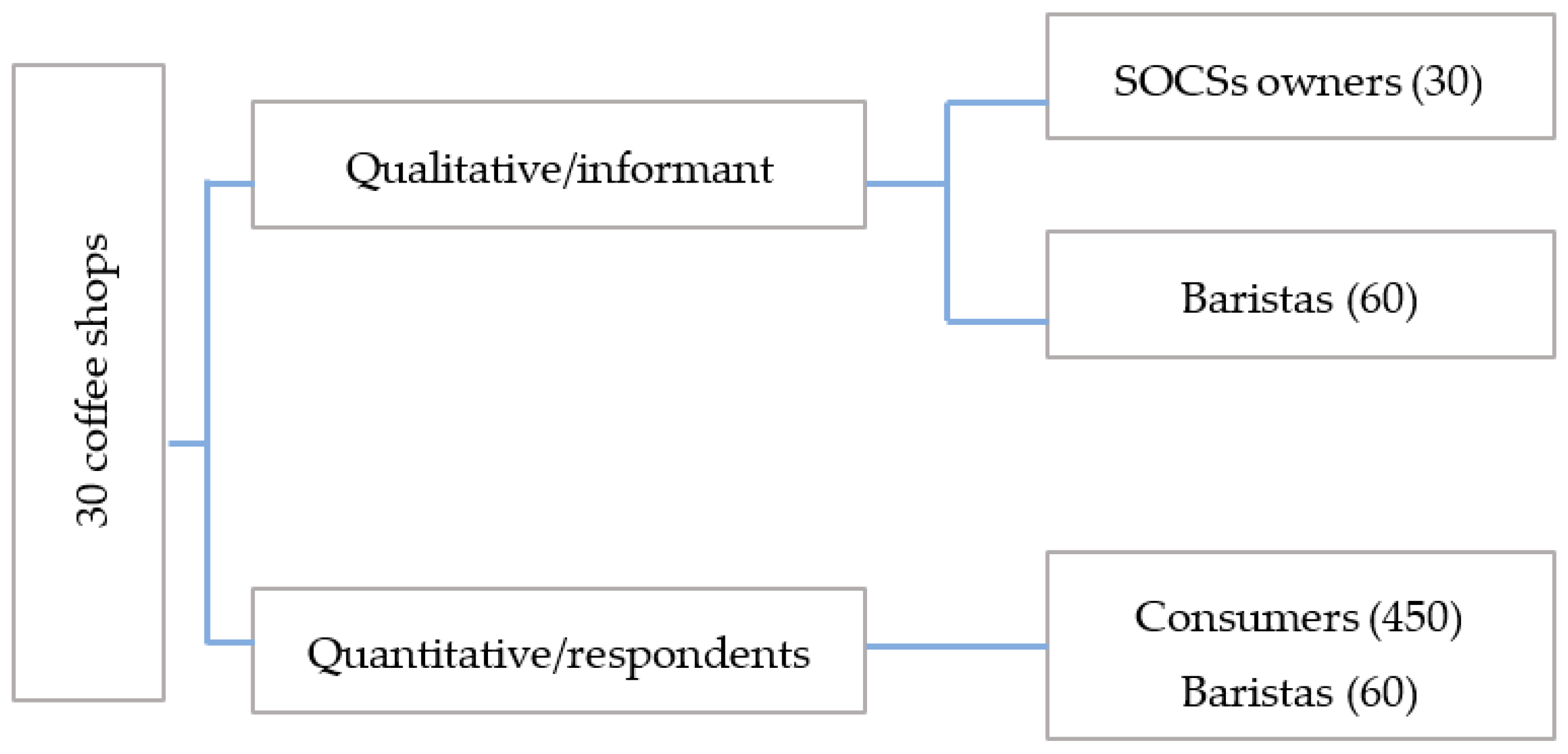

The research was conducted in Malang, the second biggest city in East Java Province with a population of more than 600 thousand people and with a significant development of coffee shops in the last ten years. Not less than 250 coffee shops with more than 100 SOCSs will keep growing over time. We have conducted an in-depth interview with 30 SOCSs owners as the key informants for a two-month field research to construct what strategies they have carried out in facing tighter competition with the usual coffee shops. At the same times, we also conducted observations and discussions with SOCSs customers to get an in-depth impression regarding the atmosphere, their preferences, and responses to their favorite SOCSs. Meanwhile, a convenience sampling with as many as 450 consumers was conducted so that the researchers can obtain respondents who have a deep understanding of single origin coffee to facilitate the data extraction process and respondents who have consumed single origin coffee. Thus, this research simultaneously uses quantitative and qualitative approaches to explain the existence of CCs and their role in driving sustainable consumption as well as improving Dynamics capabilities of SOCSs.

Figure 3 shows the stratified random sampling in determining the number of respondents and informants.

Furthermore, we asked 60 baristas to record the behavior of 450 consumers in two weeks, whether they directly order the single origin coffee type, whether they ask for the barista’s help, or whether they order coffee other than the single origin. The method of ordering is an indication of the costumers’ intensity on the coffee they drink as potential connoisseurs or connoisseur candidate. It is quite difficult to find the existence of connoisseurs among visitors because they usually get along with other visitors. Thus, special methods are needed to detect them. One of the ways is to check the existence of connoisseur consumers among shop visitors by surveying the way they order the coffee menu. If the customer chooses their own coffee, both the type and method of serving, then they are certain to pay a special attention to the goods they buy as a characteristic of connoisseur consumers. Independently choosing the type of coffee, the way it is presented, and a high intensity of visits each month are indications of connoisseur consumers. Interviews with baristas have confirmed that the coffee lovers often start a conversation with baristas about the information on the coffee origin, the serving techniques, as well as the character of the taste and aroma.

The quantitative approach aims to calculate the potential existence of CCs and to measure the relationship between CCs attributes, namely the level of the manager’s knowledge of coffee, the coffee shop image, the variety of coffee, the barista’s communication skills, and the quality of coffee serving techniques, with the number of visitors. A simple descriptive statistical analysis is used because this research focuses more on explaining social processes. Thus, the results of the statistical calculations can be used to strengthen the qualitative findings. This explanatory analysis is used to examine the causality or causal relationships between variables or to prove whether there is a relationship between purchasing decisions and various attributes of connoisseurs.

Meanwhile, a qualitative analysis is used to capture what strategies are built by managers of SOCs to improve DCs in the middle of the competition. How they sense resources, seize it, and transform business organization strategies will be described qualitatively because it involves a social process that is relatively difficult to explain with a quantitative approach. Therefore, the qualitative content analysis approach [

69], especially the strategies developed by managers of good SOCSs, starts from the sensing, seizing, and transforming processes. Simultaneously, a theme analysis [

70] was also used to map whether various sustainability attributes exist in the response of SOCSs in their efforts to provide services to the existence of CCs.

4. Results

4.1. Connoisseurs Community of SOCSs

Seen from the independent indicators in choosing the type of coffee and presentation techniques, more than 20% of coffee consumers are CCs. They are regular customers which relatively have 15 visits in a month. Therefore, the existence of CCs is very important for the sustainability of SOCS business because the loyalty level is relatively high. Based on the interviews with managers, their existence acts as the driver of SOCSs that at least is able to make the SOCSs easier to achieve break event point BEP of the business. In detail, the survey of all sample shop visitors between March and April 2018 to 30 SOCSs is presented in

Table 1.

Furthermore, to ensure the existence of connoisseur customers, we then examine whether the connoisseur’s attributes such as the depth of the barista’s knowledge of coffee, the barista’s skills, the shop image, the coffee variation, the barista’s communication skills, and the serving technique have a relationship with an increase in the number of consumers. If the three components all show a positive correlation with the number of customers, it can be determined that connoisseur customers do grow and develop among customers and are able to build communities. Therefore, if the percentage of connoisseur potential in

Table 1 and the correlation test between the connoisseurs’ attributes and the number of visitors is in line, then the existence of connoisseurs as the support of SOCSs has been verified.

The Spearman rank correlation analysis in

Table 2 shows a significant value between the depth of knowledge and the number of customers’ variables below 0.05 equal to 0.004, which means there is a correlation or relationship. Meanwhile, the value of the correlation coefficient of 0.634 shows a strong relationship between the depth of knowledge and the number of customers; it can be said that the deeper the barista’s knowledge about single origin coffee, the bigger the potential to increase the number of SOCSs customers. This is supported by the opinion of the managers of SOCS that barista’s knowledge is an important factor in their recruitment, other than friendliness and work discipline. According to the shop managers, CCs asked not only the origin and quality of the coffee they ordered but also the serving techniques and characters of various types of coffee. Managers or baristas are required to have sufficient knowledge about single origin coffee. Even some managers say that CCs will very easily move to another shop if they feel there is a peculiarity of the coffee they drink, especially the consistency of flavor from day to day.

In addition to the depth of the barista’s and shop manager’s knowledge, the management’s strategy in creating an image as a single origin shop to attract consumers can also be an indicator of the existence of connoisseur consumers. Connoisseur consumers will prefer shops that have a reputation as a single origin compared to traditional coffee, which is in accordance with their characteristics concerning the origin of coffee and the quality of serving. The above results of the Spearman rank correlation analysis show that the significant value between the shop image variable with the number of customers below 0.05 is equal to 0.032. This means there is a correlation or relationship between the two variables. Meanwhile, the value of the correlation coefficient is 0.493. This means that there is a strong relationship between the management of the shop with the number of customers. If the image of a single origin shop is increasingly highlighted, the number of customers will also increase.

In order to detect the presence of connoisseurs, a correlation between the variation of single origin coffee and SOCSs with the number of visitors was tested. Other than paying attention to the coffee they drink, CCs are usually happy to try new coffees. More varied, the coffee served will attract more customers. Among single origin shop owners, the variety of coffee provided is one of the ways they attract customers, especially coffee lovers. A correlation test on the significance value of the variation of coffee with the number of customers is below 0.05, equal to 0.003. It can be said that the two variables are correlated with each other. Meanwhile, the value of the correlation coefficient is 0.644, which means that the relationship or correlation between the variables of Shop Marketing with Number of Customers is a strong correlation. Therefore, more varied, the coffee provided by SOCS will increase the potential of the number of customers.

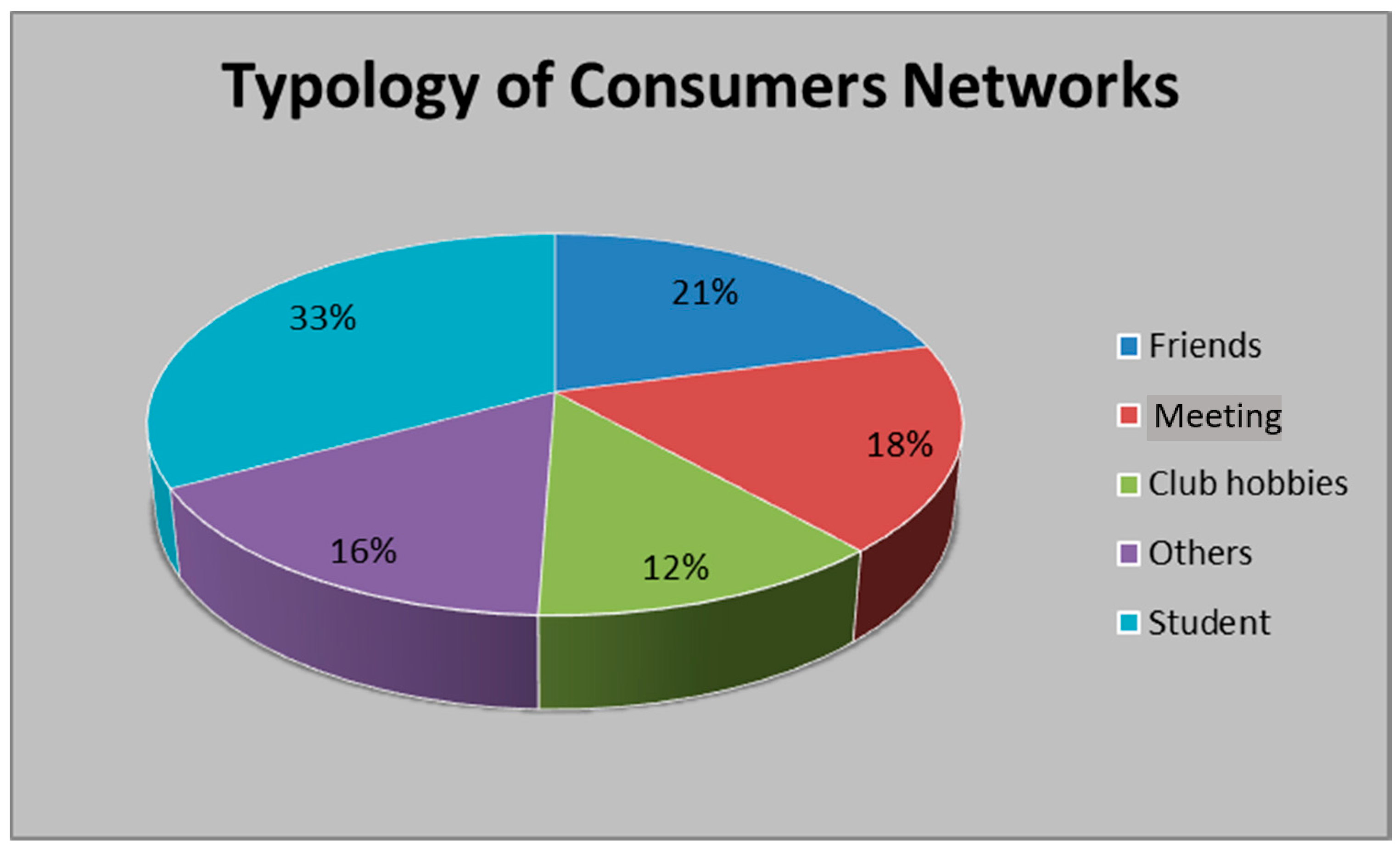

In order to strengthen the existence of CCs, we also verify the characteristics of visitors and whether it reflects the view that connoisseurs can build a cross-professional customer community or not. The survey results show that the category of consumers who have the highest percentage value in visiting coffee shops comes from friend (21%), ing (18%), and club (12); the data shows that connoisseurs truly contribute to building customer communities across professions as presented by Quintão et al. (2018) [

39]. Meanwhile, consumers who come by chance alone are only 16%; regular consumers have a good relationship with the shop manager, barista, or fellow customers. This shows that connoisseurs really exist to build a customer community for the shop. Detailed data on the consumer relations with shop and barista manager can be seen in detail in

Figure 4.

4.2. Connoiseurs Consumers and Sustainable Consumption

The relationship between connoisseurs and coffee consumption sustainability cannot be directly measured. The measurement is done through the change of management behavior to fulfill more sensitive connoisseur needs on the sustainability issues. For example, the shop must be able to explain why the price of coffee they offer is more expensive than the same coffee in the market. Consumers will perceive the goods they buy as expensive if there is no adequate explanation. This will affect their decision to buy single origin coffee. Relatively complex services and serving techniques compared to regular coffee are deemed to be not enough by the consumers to rationalize the price of coffee that can be double or triple from the regular coffee shops. The matrix in

Table 3 gives the illustration of the relationship between four sustainable dimensions with three main activities of single origin coffee business.

Apart from the above three categories, identifying the sustainability of consumption of SOCSs can also be seen from how they build their shop image as a marketing strategy. Out of 30 SOCSs, there are 60% who promote the concept of “locality” as a promotional tool to appreciate the local culture and local farmers. Meanwhile, they use the term “guest coffee” to anticipate the demand for coffee products outside the region, which is sometimes more popular. This coffee is usually only complementary. “Locality” branding is used relatively effectively by SOCS because coffee naturally has a close bond to the local culture in addition to the location where they grow. Hence, associating coffee with locality is quite effective as promotional material.

Another branding strategy that also reflects sustainability consumption is raising issues of equity in coffee distribution. Certain terms that reflect their concerns about the issue of justice are often found both in their Instagram account and in writings posted on the shop’s wall. Jargons such as “fair coffee”, “don’t drink the farmer’s blood through coffee”, or “a cup of justice” are forms of their expression to campaign for a transparent business form. Coffee shops also sarcastically comment on coffee business practices that they consider unfair with the term “Coffee is supposed to be grounded not cut” to illustrate that the sachet coffee produced by the factory is considered to be unfair. From the observations on 30 SOCSs, 70% of SOCSs used these jargons as store wall decorations or statuses on Instagram and/or Whatsapp.Education is also a common promotional topic among SOCSs as an effort to attract customers. A much as 70% of the SOCSs we surveyed used social media by posting consistent educational content about coffee. The spread of knowledge about the single origin, good coffee production methods, and good coffee brewing processes will increase their customers’ awareness about single origin coffee. Although it is not directly targeting sustainable consumption, this action certainly opens opportunities for ordinary consumers to increase their interest in coffee to become connoisseur consumers. The effort of SOCSs is quite serious in building the image of its shop to get good loyalty from its consumers in accordance with the findings of Han et al., 2018a that loyalty is an interrelation between cognitive and affective factors [

71].

Table 4 gives the illustration of the response of SOCSs management in fulfilling CCs needs.

4.3. Connoisseur Consumers and Dynamics Capabilities

In addition to moderating the sustainable consumption, this article also describes whether the existence of CCs is able to moderate the dynamic capabilities of SOCSs, namely in sensing, seizing, and transforming SOCSs. The existence of CCs facilitates the shop to map market segmentation, their preferences, as well as a which community groups should be targeted by their promotion. Thus, it will be easier for the coffee shop to synthesize and classify what resources are needed to compete. It will be easier for them to record the required needs starting from the procurement of raw materials to the marketing strategy. The trend of the type of coffee sought from the market is communicated by CCs, making it easier for the shop to plan the needs of the following month to the following year. Hence, they can build contact with farmers, green bean providers, or even fellow shop owners early on. It will be more difficult for the regular coffee shop to do the mapping because they only rely on differences in presentation. Thus, their competitiveness becomes lower. The sensitivity of the company which is driven by the existence of CCs will surely not be obtained by regular coffee shops. Hence, they have to analyze the market trends themselves in the future.

For example, SOCSs often open polls to audiences to assess new products before they are launched, with prior consideration of CCs. This is to find out how many potential customers can be attracted through social media. Polls are very efficient to map the market while avoiding a deterioration in the reputation of the new products if there is a lack of customer response because it has been announced from the beginning that the product is tentative. It will be continued if there is a positive response. The consideration of CCs and the use of this technology will provide convenience to managers in mapping the desires of consumers without requiring much energy and costs compared to traditional methods. Hence, CCs and technology allows managers to process the identification of opportunities easily, quickly, and cheaply. In other words, the existence of CCs allows the companies to easily map the resources needed.

Does the existence of CCs also moderate the process of seizing SOCSs on these mapped resources? The efforts of SOCS in designing the coffee shop to become more friendly with CCs by utilizing the resources they controlled such as coffee knowledge, single origin coffee networks, friendships, and approaching groups of hobbies to get customers is one of the moderations taken. Besides that, the existence of CCs also encourages SOCSs in Indonesia to intentionally position themselves as different shops than most of the traditional shops that have existed before; in some cases they also make a difference with the pattern of international network shops such as Starbucks and Kopi Tiam. This is in line with the finding of References [

20,

39] where the culture of coffee does not always follow a mainstream pattern such as Starbucks. However, it will always have a strong sense of locality as part of cultural alternatives. Therefore, the existence of CCs basically facilitates SOCSs to design more focused business patterns without having to carry out a tough market education process like other regular coffee shop.

In addition, the existence of CCs also moderates SOCSs to design new business segments as their way to win the competition with regular coffee shops and international network shops. As we know, regular coffee shops in the past ten years have also transformed their businesses which were not so impressive for traditional shops. However, it is more like a modern café equipped with various modern snacks. They also provide a free Internet facility to meet the communication needs of younger customers and to build a more comfortable atmosphere in accordance with the demands of today’s generation. Building an image as a coffee shop with good quality coffee and giving other ethical touches are accurate strategies of SOCSs to differentiate themselves from existing competitors.

In addition to designing businesses that are more segmented on CCs and the community of hobbies and the younger generation, SOCSs also build the characteristics of their shop by designing the shop, giving variations of the coffee served, and giving a typical service model. In addition, they usually serve some special coffee that can only be enjoyed among their own community. Some coffee networks conduct business contracts with certain farmer groups and develop brands that are only sold in their outlets. It became their specific competitiveness. Usually, they provide assistance to farmers intensively about coffee processing to get the quality, aroma, and taste according to the market needs. Using this strategy is a precise way for companies to seize existing resources. Thus, other shops will not be able to replace it because they use an exclusive business relationship pattern.

The transformation process carried out by SOCSs caused by the growth of fairly large CCs in the past ten years are also due to a shift in the impression that coffee is identical to an old, masculine, ancient tradition. Hanging out in a coffee shop, especially in single origin shops, is a new lifestyle for the younger generation. In addition, the old and masculine impressions are beginning to erode. It is clear that the role of SOCSs is to change that impression by showing their female customers pictures on a social media page. Coffee is a cross-generational drink. SOCSs are also a convenient place for anyone, including women. As we know, ten years ago before the coffee culture developed in Indonesia, women who spent their time in coffee shops would be considered as unusual. The impression was the same even in a big city like Jakarta as a cosmopolitan city. In some shops, since the coffee culture boomed around the 2000s, they began employing women as baristas or shopkeepers.

Another corporate culture that has changed to face the competition is the principle of increasing added value rather than selling price monopoly. This is different from regular shops that are still focused on providing low prices to customers which is causing relatively small sales margin. This added value can be in the form of service, the quality of the coffee taste, a free Wi-Fi facility, and the convenience of the shop’s atmosphere. This increased added value is believed to be far better than competing prices because they are well aware that their segmentation is not a customer who is hunting for price incentives. This situation cannot be separated from the existence of CCs as their customers, whose numbers continue to increase, along with social contacts occurring in shops among fellow customers.

Another transformation carried out by SOCSs is building networks among them, both as a means of communication and as the building of a good business environment. This network is also directly used to exchange information and even information on the procurement of raw materials. If a regular shop relies on raw materials from the market, then a single origin shop uses the network more to fulfill their raw materials needs. The alliance of the owners of the SOCSs are also used to procure a shop’s equipment as well as cooperation in following certain moments for the purpose of promoting coffee culture. Schematically, the role of CCs in increasing DCs SOCSs can be seen in

Figure 5 below:

5. Discussion

Seeing the existence of promising CCs of more than 20% of total shop visitors from the survey, it is very natural for the shop to make various efforts to meet the tastes of CCs, starting from providing a large variety of single origin coffee, building a shop that cares about farmers, and developing a shop relationship with more open and egalitarian customers. It is not just a number; CCs are also able to build a community both with regular consumers or fellow CCs. Thus, its existence has two attractions for regular visitors, friends, and coffee lovers. This confirms the theory that CCs are able to build subcultures and communities, both with regular consumers and outstanding professionals [

32,

39].

To prove there is a connection between the existence of CCs and customers, a descriptive statistical test on four indicators was carried out, namely (1) the level of the manager’s knowledge about coffee, (2) the image of the shop (café or coffee shop), (3) the variation of single origin coffee, (4) the barista’s communication skills, and (5) the coffee serving technique, and had a close relationship with the number of visits. Although we do not specifically see the existence of CCs, the close relationship between these categories can be used as an initial indication that CCs are indeed able to attract visitors, both regular visitors and professional coffee lovers. Discussions with baristas in some shops also show similar conditions where consumers are increasingly critical of the coffee they are served. The manager also asks customers’ opinion on whether the coffee they were served was satisfying or not. By seeing this data, it can be seen if the manager consciously maps the consumer characteristics and identifies the level of satisfaction.

Furthermore, is there a connection between the existence of CCs and sustainable consumption? The existence of these CCs is responded by SOCSs by building a business that is indirectly related to sustainability. The process of transferring green knowledge to baristas so that they can explain to customers that ask about coffee is an indication that CCs indirectly drive the sustainability consumption. The demand to obtain good raw material has encouraged SOCSs to provide assistance to the farmers either in a group or solo so that they can make efficient energy consumption at the farmer level in processing good coffee beans. They inevitably have to teach environmentally friendly production methods and hygienic coffee bean processing. This will encourage sustainability at the farmer level. The social interaction that they build with farmers, as well as other shops, has encouraged an increase in the price of coffee beans at the farmer level. This relationship causes farmers to know the margins obtained by SOCSs, forcing the shop to increase their sharing by buying with far more expensive prices than market prices. Thus, the existence of CCs has indirectly encouraged transparency in the SOCSs’ business process, which is theoretically an indication of sustainability.

If CCs moderate sustainable consumption, does their presence also moderate the increase in dynamic capabilities of SOCSs as business institutions? This research shows that the existence of CCs allows the business owners to easily map the resources needed by the company because the company only needs to focus on mapping the resources needed to serve CCs, such as the best quality coffee and good-skilled baristas. These companies do not need to map the resources needed by most consumers because if the needs of CCs are met, new subcultures and communities will be built. Thus, CCs are able to moderate SOCSs to increase their sensing capabilities towards the resources needed so as to improve their dynamic capabilities.

Seen from the side of seizing, CCs moderate SOCSs by opening the opportunity for the store to build a community of coffee lovers to the level of farmers through CCs connections. In addition, the existence of CCs itself facilitates SOCSs in choosing a shop theme by promoting locality and using organic promotion, fair trade, and other ethnic attributes, which is also a form of seizing other SOCSs. Meanwhile, on the side of corporate transformation, the existence of CCs encourages SOCSs to mobilize alliances with fellow shops and to build networks with farmers. The efforts of the owners of SOCSs to build different cultures within their company organizations that reflect attention to ethical attributes are part of the transforming company. By that, the existence of CCs eases the SOCSs to improve the ability of seizing and transforming the companies.

6. Conclusions

This research confirms that CCs are an important component of the sustainability of SOCSs amid the intense competition both with traditional coffee shops and international coffee shop chains. The potential of their existence to be more than 20% of visitors urge SOCSs owners to design their business model according to the needs of CCs. This clearly shows that CCs are part of the consumer. The analysis on the attributes related to CCs’ attributes such as the improvement of manager’s knowledge on coffee, the image of the coffee shop, the coffee variation, the barista’s communication skills, and the quality of the coffee serving technique show a positive relationship with the number of consumers. These findings are in line with the opinions by References [

19,

31,

32] which stated that CCs are agents that are able to build communities both with professionals and regular consumers to form new subculture and communities.

Furthermore, it is correlated with the indicator sustainable consumption; the existence of CCs, directly and indirectly, encourage the sustainability of consumption because SOCSs carry out the transfer of green knowledge, saves energy consumption, increases the transparency of business processes, and reduces the negative impact of waste in its business processes on three main aspects of business, namely production, consumption, and distribution. Loyalty and high concern for ethical attributes of coffee are referred to by SOCSs to design and build more environmentally friendly businesses to adapt to these attributes.

At the same time, the existence of CCs also improves the dynamic capabilities of SOCSs because it allows for SOCSs to easily map resources, acquire these resources, and design company businesses by utilizing these resources appropriately. CCs also moderate the process of seizing SOCSs because it eases SOCSs to build a business model that suits their needs. CCs also facilitate SOCSs to transform corporate culture into being more adaptive to consumer demands. At the same time, more than 20 SOCSs claim that they feel easier when building alliances with fellow shop owners and building networks with farmers that are facilitated by CCs to continue to improve their competitiveness. Hence, CCs are very important, both directly and indirectly pushing the sustainable consumption and making it easier for SOCSs to build strong dynamics capabilities in order to compete with traditional shops or international network shops.

Therefore, it can be seen that the existence of CCs stimulates SOCSs management to design their business to better suit their characteristics, thus making CCs an important mediator in building sustainable consumption. CCs are able to attract not only loyal customers but also groups of professionals to become customers. However, the level of loyalty and its dynamics in the community formed by CCs cannot be explained in this research. One of the managers of SOCSs said, “[CCs] are the savior of our cash flow other than to attract their friends to join. Their arrival at our shop also encouraged us to continue to improve our coffee knowledge to avoid embarrassment.” Obviously, the two functions played by CCs as consumers are the drivers of the shop’s income and as a symbol of the presence of coffee lovers. Based on the above findings, more in-depth research on the standard character and number of CCs is needed as well as their contribution to the revenue structure of SOCSs. Meanwhile, connoisseur customers’ support is capable of helping the SOCSs in improving their DCs to improve the sustainable consumption of coffee as a commodity in the future.