Abstract

This work is about how healthcare issues can be reframed from a sustainable and inclusive development perspective. Focusing on the case of orphan drugs and rare diseases, first, a country-based review of the main regulatory approaches to orphan drugs is conducted; then, the main contributions of the literature are reviewed to identify dominant views and the way the problem is more commonly framed. The main findings reveal that the dominant regulatory approaches and theoretical interpretations of the problem are mainly based on economic considerations. However, this does not seem to have led to very satisfactory results. Reflecting upon what the sustainability perspective can highlight with reference to healthcare, substantial connections between the orphan drugs issue and that of neglected diseases are highlighted. These connections suggest reframing the orphan drugs issue as a social equality and inclusiveness problem, hence the need to adopt a sustainable and inclusive development perspective. As a key sustainable development goal (SGD) to be shared by all nations, healthcare should always be approached by putting the principles of sustainable and inclusive development at the core of policy makers’ regulatory choices. Accordingly, we think that the orphan drugs issue, like that of neglected diseases, could be better faced by adopting a social equality and inclusiveness perspective.

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to provide a renewed interpretation of the orphan drugs and rare diseases healthcare issue from a sustainability and sustainable development perspective. It is widely recognized that healthcare is the complex whole of institutional and organizational structures whose actions impact the well-being of communities. Hence, the societal dimension of healthcare is evident and should always be placed at the center of policy decision making. However, although intrinsically inspired to take care of human beings and their environments, over time, healthcare policies have had to deal with the common problem of resource scarcity. Subsequently, healthcare policies have been directed towards priority-setting and rationing processes, which often lead to unpopular decisions that negatively affect communities [1]. As long as economic concerns are relevant, problems of equality and justice in access to healthcare inevitably emerge.

Organizing an effective, equitable, efficient, and sustainable healthcare system is the task of any nation’s policy makers. However, while almost any healthcare system would ideally try to provide the highest level of accessible and equitable healthcare possible, expense limits do not always allow this ideal goal to be achieved.

Among the healthcare issues that cause explicit economic concern, the debate about “orphan drugs” and “rare diseases” is particularly challenging and requires more attention [2].

The health needs of patients affected by rare diseases are underserved because the market they define is too small to justify the commercial interest of drug development. To encourage the development of drugs intended to treat such rare diseases, several countries have adopted specific regulatory systems. Nevertheless, development of these drugs remains expensive, and their cost is high. Moreover, as highlighted by Drummond et al. [3], standard methods of health technology assessment (HTA) that incorporate economic evaluation do not prove orphan drugs to be cost-effective. This limited cost-effectiveness associated with their high cost limits funding and patient access and creates restrictions that conflict with societal preferences. On the basis of this evidence, Drummond et al. discuss the adequateness of standard methods of HTA supporting decision-making on patient access to orphan drugs and their funding. They outline “a research agenda to help understand the societal value of orphan drugs and issues surrounding their development, funding, and use” [3] (p. 36).

Following the main theme of this research agenda on the societal value of orphan drugs, we focus on two important objectives [3] (p. 41): (1) to update current processes for assessing and appraising drugs to make them suitable for orphan drugs; (2) to make more explicit all the elements of societal value in existing decision-making procedures. The two issues are related and should be the starting point to rethink the approach to orphan drugs.

Shifting from a health economics to a managerial perspective, this paper provides arguments in favor of making the societal value of orphan drugs more explicit by reframing them as a sustainable development issue. This issue then becomes similar to that of neglected diseases, which are diseases important (in terms of numbers of affected people) that do not create markets profitable for companies; for this reason, they are “neglected” by drug developers or by other institutions in drug access. The most common types of neglected diseases are tropical diseases, many of which are caused by parasites that are spread by insects or contact with contaminated water or soil. As is clarified in detail in Section 5.3, neglected diseases are nothing but rare. However, for several reasons, they are overlooked by drug developers or by health government institutions and news media. Examples of such parasitic diseases include American trypanosomiasis (which affects more than 13 million people), Leishmaniasis (which affects more than 12 million people), and the Lymphatic filariasis (which affects about 120 million people) [4].

To develop the study, essential materials for discussion were collected regarding the way nations, policy makers, and literature interpret the problem. The key results are summarized to show the main policy and theoretical approaches to orphan drugs and rare diseases. Subsequently, an interpretative proposal that adopts the sustainability and sustainable perspective is developed.

The study also provides an example of “what sustainability can offer to healthcare” (a call launched by the Special Issue “Sustainability for Healthcare”) by re-exploring the societal perspective of healthcare within a revisited framework where the sustainability and sustainable development principles are incorporated.

2. Orphan Drugs: Definitions, Facts, and Scope of the Issue

One of the most important reference databases for the orphan drugs issue in Europe, Orphanet, a European organization involving 40 countries worldwide, defines “orphan drugs” as drugs “intended to treat diseases so rare that sponsors are reluctant to develop them under usual marketing conditions” [5]. Hence, the notion of the orphan drug is strictly connected to that of a rare disease—a rare disease becomes an orphan disease when its rarity implies the lack of a market large enough to gain support and resources to discover treatments for it.

Given that the development process—from the discovery of a new molecule to its marketing—takes about 10 years on average and is very expensive and uncertain, it is clear that rare diseases do not allow the recovery of the capital invested for research. Hence, orphan drugs, although potentially available for public health needs, are not developed by the pharmaceutical industry for economic reasons. A drug may also be considered “orphan” when, although available for treating a more frequent disease, it has not been developed for another rarer condition.

Orphanet distinguishes three main cases [5]:

- Products intended to treat rare diseases: developed to treat patients suffering from serious diseases for which no treatments are available or satisfactory. The number of such rare diseases is estimated to be between 4000 and 5000 worldwide.

- Products withdrawn from the market for economic or therapeutic reasons: diseases for which no satisfactory treatment is available.

- Products that have not been developed: this is the case of products derived from a research process that cannot be patented or of products that concern important but unprofitable markets (as in the case of third-world countries).

According to Eurordis, a large patient organization in Europe, there are more than 6000 rare diseases that may affect 30 million citizens in the European Union [6].

As Scieppatti et al. argue, “Rare diseases are an important public health issue and a challenge for the medical community” [7] (p. 2040). They were recognized as a policy issue for the first time in 1983, when the United States adopted the Orphan Drug Act; then, they were recognized in Japan in 1993; in Australia in 1997; and finally in Europe in 1999, adopting a common EU policy on orphan drugs [8].

Despite the importance of the orphan drugs and rare diseases problem, common definitions are still lacking, and countries adopt different classification criteria [9]. Apart from formal definitions, what differs in each country is the “cut-off value” of people affected by a disease on the basis of which it can be considered “rare”. Clearly, this variable number reflects the policy conditions under which the definition is adopted because the criterion relevant to determine the number is not the rarity in itself but the access of companies to development incentives that can be sustained by the country.

To overcome the problem of pharmaceutical companies not being economically interested in investing in developing or producing an orphan drug to treat a rare disease [10], several kinds of incentive mechanisms have been devised [11]. These incentives are essentially of three kinds: tax credits and research grants, simplification of marketing authorization procedures, and extended market exclusivity [12,13].

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, the methodology adopted for the study is illustrated. First, there is a review of the main orphan drugs regulatory approaches at an international level to understand the logic and views behind the regulatory process in the various nations selected. Subsequently, a brief literature review identifies the mainstream and dominant perspectives used to interpret and address the problem. Comprehensibly, the main literature regarding orphan drugs and rare diseases comes from the chemical and pharmaceutical scientific domains. Subsequently, a gap in knowledge emerges about the societal aspects of the problem [14]. Many contributions deal with “technical” aspects of the drugs and treatments of rare diseases [15,16,17]. Other contributions provide a managerial, marketing, and organizational view of the problem [8,18,19]. Some of them focus on more specific aspects such as: the definition of orphan drug characteristics for specific health issues and their pivotal clinical trials in comparison with common drugs [20]; the processes for identifying and sharing possible solutions for managing orphan diseases [21]; the implications of orphan drugs for the economic viability of pharmaceutical companies [22].

Our focus, however, is on the policy aspects of this issue in order to know the way the problem is generally approached by existing literature. Therefore, a literature review was used to ensure rigor and replicability of the research process [23,24]. Following PRISMA guidelines [25] and in line with Tranfield et al. recommendations [26], a three-step process was used, which consisted of (1) planning the review, (2) conducting the review, (3) and analyzing the results.

Firstly, in the planning phase, inclusion criteria were identified as summarized in the following Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for literature review.

Data for literature review were collected between April and October 2018 from Web of Science and EBSCO databases. These databases were selected because Web of Science tends to contain articles from high ranked journals [27], while EBSCO includes articles from multiple disciplines and research fields [28].

Data were selected searching for the term “Orphan Dru*” in the title of all English contributions published from 2012 to 2017.

Applying inclusion criteria and screening the abstracts of the contributions identified, 400 contributions from the Web of Science database and 120 contributions from EBSCO database were included in the literature review. Once the 520 articles were retrieved, a suitable database for the research was developed.

The contributions identified were organized through a database using well-known bibliometric characteristics (e.g., author, year, journal, subjects, publishers, abstracts, and keywords).

4. Results

4.1. An Overview of Key Regulatory Approaches to Orphan Drugs

The first recognized classification of orphan drugs related to rare diseases was provided in 1983 by the Orphan Drug Act [29]. The Orphan Drug Act officially recognized that pharmaceutical companies were not interested in developing drugs to treat orphan diseases due to the low number of patients and, consequently, the low commercial attractiveness of the investment [30,31]. Applying this law, pharmaceutical companies willing to produce orphan drugs have been guaranteed various economic incentives such as tax credits, research grants, and market exclusivity [32,33].

After the introduction of the Orphan Drug Act, the Food and Drug Administration has recognized more than 3500 cases of orphan diseases and has approved more than 500 orphan drugs [31].

Different views and approaches to orphan drugs are briefly reported in Table 2, which summarizes the key elements.

Table 2.

An overview of the main approaches to orphan diseases.

From the analysis of the main regulatory approaches to orphan drugs, some variety emerges in the recognition criteria. Compared to the USA, which introduced the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, in Europe, the Orphan Drug Regulation 141/2000 considers as orphan diseases all the health disorders that affect less than five people out of every 10,000 citizens [32]. In Japan, three conditions must be satisfied to classify a disease as orphan—an impact on less than 50,000 citizens, the absence of available health treatment, and the possibility to define a clear product and scientific development process for the disease. In Australia, the Therapeutic Substances Regulations state that a disease can be considered orphan when it affects less than 2000 citizens in one year [13]. In India, a specific regulatory framework for orphan diseases has been discussed after the request formulated in 2001 by a group of pharmacologists during a conference held by the Indian Drugs Manufacturers Association [30]. In Taiwan, orphan diseases are regulated by Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan [32]. In Korea, orphan diseases are health disorders that affect less than 20,000 citizens or for which treatments are not available [33]. Finally, in Hong Kong, orphan drugs are regulated by the Department of Health and the process for approval of new orphan drugs is disciplined by the New Chemical Entity (NCE) [32].

By identifying the main similarities of the regulatory approaches reported above, it is possible to group them into macro-geographical areas, as reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

A summary of the main regulatory approaches to orphan drugs.

4.2. Results of the Brief Review of the Orphan Drugs Literature

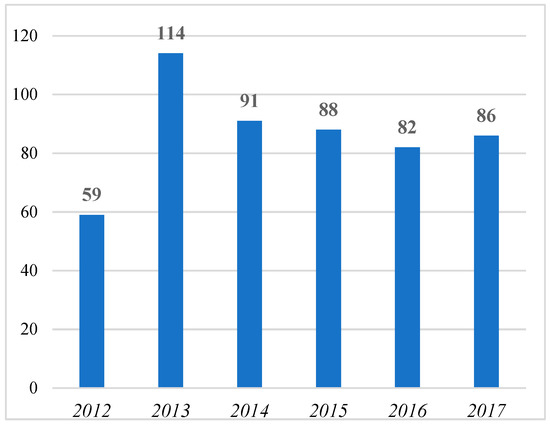

From the following Figure 1, it seems that interest in the domain of orphan drugs after increasing from 2012 (59 contributions) to 2013 (114 contributions) has been progressively reducing in the subsequent years.

Figure 1.

Number of contributions with “orphan dru*” in the title from 2012 to 2017 (per year).

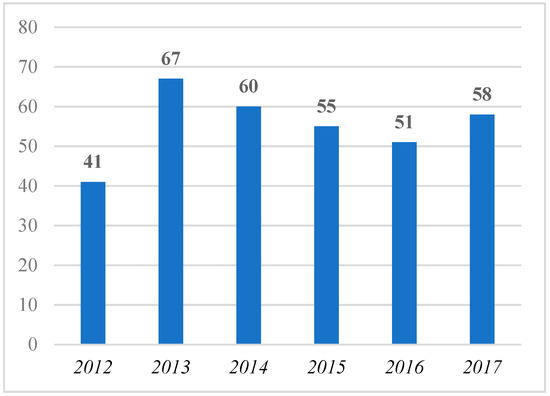

The same trend is confirmed by considering the number of journals that have published contributions with “orphan dru*” in their titles. Figure 2 shows that after growth in the number of the journals that published contributions with “orphan dru*” in their titles from 2012 (41 journals) to 2013 (67 journals), there is a negative trend in later years.

Figure 2.

Number of journals that published contributions with “orphan dru*” in the title from 2012 to 2017 (per year).

Exploring the 225 journals that published contributions with “orphan dru*” in their titles from 2012 to 2017, it emerges that only two of them (“Chinese Journal of New Drugs” and “Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases”) published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for each year of the analyzed period, while:

- Three journals (“Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal”, “Expert Opinion on Orphan Drugs”, and “Nature Reviews Drug Discovery”) published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for five of the six investigated years;

- Eight journals (“BioWorld Insight”, “Chain Drug Review”, “Deutsche Apotheker Zeitung”, “Drug Discovery Today”, “Manufacturing Chemist”, “Pharmazeutische Zeitung”, “PLoS ONE”, and “Worldwide Biotech”) published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for four of the six investigated years;

- 13 journals published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for three of the six investigated years;

- 33 journals published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for two of the six investigated years;

- 166 journals published at least one contribution with “orphan dru*” in its title for only one of the six investigated years.

Considering the main research interests of the analyzed journal, it emerges that:

- 27 journals are interested in the Business, Law, and Economics fields;

- 25 journals are interested in the Health Policy field;

- Seven journals are interested in the Innovation and Technology fields;

- 165 journals are interested in the Medicine and Pharmacy fields;

- One journal is interested in the Science field.

Clearly, the major interest in the issue of orphan drugs is within the Medicine and Pharmacy fields, while the other fields show very low interest.

Analyzing the abstracts of the 530 contributions identified, about 80% underline the willingness of the authors to provide technical contributions about health treatments, processes, and products to face the challenge of orphan diseases. More than 10% of them focus on policies to manage dynamics and processes related to orphan diseases, and about 15% of them investigate managerial models and approaches related to orphan drugs.

The keywords of the 530 identified contributions reveal great attention to the economic aspects of the orphan drug domain, using terms such as “health technology assessment” (in 22 contributions), “market*” (in 14 contributions), “pricing” (in eight contributions), “costs” (in 10 contributions), “economy*” (in six contributions), and “value” (in six contributions).

Overall, what emerges from this search is a narrow view of the problem with a dominant economic perspective. In the existing literature, the policy problem is mainly discussed from the pharmaceutical companies’ point of view with the aim of solving the economic interest problem [42,43,44,45,46]. For example, focus is on the impact of market regulation on pharmaceutical companies’ survival [47,48,49,50], the amount and conditions of public grants [51,52,53], the time and implications of market exclusivity [54,55,56], and the role of technology to ensure better identification and access to health treatments in the case of orphan diseases [57,58,59]. Finally, only a few contributions focus on the patients’ and citizens’ viewpoint [60,61,62]. Their role has been considered in defining strategies and plans for orphan drugs and rare diseases management in few legislative initiatives [63]. In Europe, since the European National Plans or Strategies on Rare Diseases (Nr. 14) identified research into rare diseases as one of the priorities for the healthcare system, patients’ engagement in the debate about orphan drugs and rare disease has dramatically increased. There is particular interest in several aspects such as knowledge acquisition, collaboration in clinical research, and suggestions for regulatory aspects, pricing, and reimbursement decisions [64].

Several surveys have been conducted to clarify the patients’ perspectives about approaches and strategies in orphan drugs and rare diseases management [65]. A survey conducted by Linley and Hughes [66] on 4118 adults in Great Britain investigated citizens’ preferences in the health domain by asking to allocate ex-ante defined funds between different patients and diseases. The survey shows that, in the case of cost trade-off conditions, there is a general preference towards patients that are costlier to treat. According to the authors, “the most plausible interpretation (for the results) is that respondents are expressing a general preference for fairness in access to treatment based on need, irrespective of ability to benefit or cost rather than a preference for the criterion in question per se” [66] (p. 957).

With reference to the apparent missing rationality in the patients’ choices, McCabe et al. [67] distinguish between “horizontal equity” (equal treatment of equals) and “vertical equity” (unequal treatment of unequals). Horizontal equity states that taking money from the national health care budget to tackle the orphan drugs and rare disease issue is not what communities want, while recognizing that citizens affected by rare diseases, as a minority, are entitled to specific health treatments.

However, the problem is not so much about including the patients’ and communities’ perspectives in the regulatory choices for orphan drugs. Rather, as discussed in Section 5, the problem is about how the societal view is adopted. This perspective reveals connections between the case of orphan drugs and that of neglected diseases.

Various literature contributions see the connection between the cases of orphan drugs and neglected diseases. Grabowski [68], for example, conducted a review of literature on the topic, highlighting the low level of investment in research and development (R&D) activities and medical programs to deal with diseases that affect developing countries on the basis of lessons learned from the Orphan Drug Act. Other contributions are provided by Gericke et al. [69], who discuss possible lines of action, and Morel at al. [70], who focus on the need for multidisciplinary approaches.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Traits of the Main Regulatory Approaches to Orphan Drugs

Summarizing the key traits of orphan drugs’ approaches displayed in Table 3, the following macro areas can be defined:

- Africa and Oceania, where there is no clear approach to orphan drugs and rare diseases issues. Few incentives are given to companies interested in contributing to the research on orphan diseases, and low attention is paid to the topic of orphan diseases from a social perspective [42].

- Europe, where the topics of orphan drugs and rare diseases are debated from both economic and social perspectives. Several guidelines are proposed to face problems; multiple strategies are planned to support pharmaceutical and health companies’ involvement in defining shared approaches, and several activities are organized to promote bottom-up involvements of citizens and local organizations [71].

- Asia, where the societal view seems to prevail. Several incentives are given to companies interested in contributing to the orphan drugs issue, but their application is always linked to the possibility for the population to obtain more effective health products and services [33].

- America, where the main guidelines and strategies regarding the orphan drugs and rare diseases issue are defined more by considering the view of health and pharmaceutical companies. There are few activities to increase citizen participation and to evaluate the sustainability of companies’ strategies [72].

Overall, it emerges that orphan drugs and rare diseases are a relevant issue to manage in order to ensure equality in healthcare for the global population; however, the approaches vary significantly.

Despite the increasing attention stimulated by the Orphan Drug Act and similar laws in other countries, as well as the growing institutional commitment to the problem, these incentive mechanisms do not seem to have provided definitive solutions. In Europe, a study conducted in 2013 by Joppi and Garattini [10] analyzed the orphan drug recognition process in the four years after the introduction of sector legislation. It seems that only 18 out of 255 applications were approved for marketing, mainly on the basis of cost-effectiveness and economic sustainability analysis. The high prices of many drugs and the difficulty of access to health treatments for orphan diseases are still unsolved problems [73].

The data shows:

- A dominant pure cost-effectiveness analysis in the evaluation of orphan drugs and diseases [74]. As Aronson argues [9], the main criterion currently used by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for the approval of an orphan drug is its cost. In several countries, like the United Kingdom, recognition as an orphan drug and the related advantages for pharmaceutical companies are not implemented unless their costs are below £30,000 per Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY).

- Insufficient success in implementing (economic) incentive mechanisms to support research, development, and marketing of orphan drugs. In the USA, for example, after the introduction of the regulation, from 1983 to 2002, about 1100 drugs and biological products were proposed as orphan products, but only 231 were approved [9].

- Millions of people all over the world are reported to be affected by rare diseases with no access to potentially available treatments.

In summary, the above analysis reveals that the problem of orphan drugs suffers from dominant attention to economic evaluations, which has affected the development of models and approaches in the management of the orphan drugs and rare diseases issues [75]. These economic aspects influence the intrinsic societal nature of healthcare that would primarily consider the equity and ethical dimension of the problem [76]. The high interest of pharmaceutical companies in market exclusivity and economic performance generally overshadows the social dimension of healthcare. Evidently, this problem is even greater in the case of orphan drugs and rare diseases [77].

The main regulatory approaches to orphan drugs can be distinguished by comparing the economic and the societal perspective on the “equality” of healthcare policies. A matrix can be built representing the current dominant approaches identified in Table 3 (Table 4), highlighting the relevance of the societal and economic perspectives. The matrix shows that, while the European approach is characterized by greater attention to both the societal and economic aspects of the problem, the American approach is more focused on the economic perspective given the high interest in market regulation. In the Asian approach, however, the focus is more on the societal perspective given the high interest shown in community well-being. In the African-Oceanian approach, dominant attention to social well-being or market interest does not emerge. Evidently, in each country’s regulatory approach, the dominant culture of the country is revealed.

Table 4.

A matrix representation of dominant regulatory approaches to orphan drugs and rare diseases.

5.2. Main Literature Perspectives on the Orphan Drugs Problem

Analysing the existing literature on orphan drugs and orphan diseases, three main perspectives can be identified and are reported in Table 5—a technical-scientific perspective that focuses on chemical, biological, and pharmaceutical aspects, an economic perspective that focuses on market and risk aspects, and a managerial perspective that focuses on organizational and business aspects of the pharmaceutical companies working in the area of orphan drugs.

Table 5.

Main perspectives of existing literature on orphan drugs and diseases.

The literature confirms that the current regulatory and theoretical approaches show a dominant interest in the economic aspects of the problem. It confirms the lack of the societal view of the problem in policy-making terms

Many scholars, however, highlight the necessity to include ethical or societal considerations in the debate about orphan drugs. For example, in his contributions on the extraordinary pricing of orphan drugs and the Socially Responsible Strategy for the U.S. Pharmaceutical Industry, Hemphill distinguishes between four expectations [42] (p. 227):

- The economic one, which “requires that a business have a social responsibility to manufacture products and offer services that society demands and to sell them at a profit”.

- The legal one, which requires that a business “remain economically viable while complying with the laws and regulations of the sovereign nation”.

- The ethical one, which “involves a moral obligation to embrace those activities and practices that are expected, or prohibited, by society even though they may not be codified into law”.

- The discretionary one, which requires that “business be a good corporate citizen by contributing to the overall well-being of the community through philanthropic activities”.

In the same direction, Denis et al. [74] (p. 345) underline that the social dimension in the orphan drugs and rare diseases debate should be more widely investigated for three reasons:

- The high price of orphan drugs that “raises the question as to the extent to which high prices are indeed a fair reflection of the costs incurred by the industry rather than serving to generate profits for the industry”.

- The evidence that “some orphan drugs do not require a high level of investment to bring the drug to market”.

- The fact that “the lack of economic viability can be questioned for certain orphan drugs that have proved to be effective against multiple (sometimes non-orphan) diseases and, thus, target a larger number of patients”.

More generally, the existence of different national approaches, views, and instruments reveals the disparity in the treatments of people affected by rare diseases. Healthcare is a global concern, and people should be treated equally. Hence, global harmonization to ensure universal and equitable access to healthcare is required with the same opportunities and conditions. Agreeing with Wästfelt et al. [79], the first step to dealing with the orphan drugs and rare diseases issue requires identification of possible alignments among the multiple regulations, definitions, and stakeholders’ interests.

On the basis of the main evidence collected, in the following section, a possible narrow view of the problem in both policy and literature approaches is highlighted, hence, the need for a perspective change.

5.3. From Rare to Neglected Diseases: A Perspective Change towards a Sustainable and Inclusive Healthcare View of the Orphan Drugs Issue

Drummond et al. [52] (p. 39) underline the necessity of “understanding the societal value of orphan drugs”, while Cohen and Felix [85] and Denis et al. [74] argue that most of the studies on managerial and government practices related to orphan drugs and rare diseases are strongly affected by the economic perspective. We believe that this dominant view has reduced attention towards the societal side of the problem with several (negative) implications in terms of equality in patient access to health services and processes [86]. As Diener and Seligman affirm [87], well-being and health cannot be analyzed only in the light of their economic impact without considering the social aspect. A perspective change is needed to broaden the way the orphan drugs and rare diseases issue is framed.

Therefore, given the limited success of current incentive mechanisms (the consequence of the way the problem is currently framed) and following the Japanese view, we believe that different reference frameworks should be adopted. The orphan drugs problem should be reframed to incorporate greater attention to the level of societal well-being of the population. Recognizing the parallel needs to ensure the sustainability of treatments, the problem then becomes how to reconcile the economic with the societal perspective in a single framework based on the general principle of preventing individual interests from compromising the policy strategy [88].

In the search for possible references to reframe the orphan drugs issue—making the societal view more explicit—we find possible answers in the similar case of neglected diseases. As mentioned, this is the case of third-world countries, which more clearly demonstrate the societal impact of the problem.

Neglected diseases are conditions that inflict severe health burdens on the world’s poorest people [89,90]. The people who are most affected by these diseases (more than one billion) are the poorest populations living in remote rural areas, urban slums, or conflict zones under conditions of poverty with unsafe drinking water, poor sanitation, substandard housing, and little or no access to health care [91]. These diseases are called “neglected” because they are often overlooked by drug developers or by other institutions in drug access (government officials, public health programs, news media, etc.). Typically, as with orphan drugs, private pharmaceutical companies cannot recover the cost of developing and producing treatments for these diseases, although for different reasons. Moreover, neglected diseases regard people “outside” the geographical areas of developed nations and do not usually cause dramatic outbreaks that kill large numbers of people, but “only” lead to crippling deformities, severe disabilities, and/or relatively slow deaths over a longer period of time [92].

Therefore, in the case of neglected diseases, the problem is neither their rarity nor the size of markets. What neglected diseases have in common with the orphan drugs issue is lack of the economic interests necessary to profitably market them. Conversely, neglected diseases and orphan drugs issues differ in that the former concern large numbers of people in undeveloped countries while the latter regard small numbers of people in developed countries. This means that the distinguishing element is essentially economic. It is the economic dimension, which developed countries focus on, that makes the same problem different. People with no access to available treatments depend on policy makers to provide regulation in the case of orphan drugs; conversely, they are simply neglected in the poorest countries.

Including the case of neglected diseases in our analysis helps us to find a direction to reframe the approach to orphan drugs by more explicitly including the societal perspective as a priority to be reconciled with the economic aspects of the problem. Here, we think that the sustainability framework has something to offer to healthcare.

Sustainability and the related concept of sustainable development are conceptual umbrellas including a wide range of life issues of social, environmental, and economic nature that impact human survival and viability over time [93,94,95,96,97].

Adopting a sustainability perspective to address healthcare issues provides us with interpretative tools more appropriate to address the reframed orphan drugs issue coherently and effectively. It becomes a matter of sustainable development to promote the universal concept [96] of “ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages”, which is the third of the 17 United Nations SDGs with 13 targets measured through 26 indicators [98].

The neglected tropical diseases are explicitly mentioned among the SDG targets. Similarly, providing universal access to quality and affordable medicines is explicitly mentioned as a key target.

Framed as a matter of development, healthcare explicitly incorporates an inclusiveness and equality perspective [99]. In this light, orphan drugs together with neglected diseases represent typical healthcare contexts of action for SDGs, as they can be emblematic of situations of inequality. The economic problem cannot be the dominant element of reasoning and decision-making. Accordingly, the problem of limits in the use of resources should be faced through the definition of new conditions for balance [100].

Healthcare should be linked to the multidimensional framework of sustainability by focusing on its social dimension in terms of societal development and at the same time reconciling this need with that of economic (as well as environmental) sustainability [101]. Healthcare is affected by increasingly dominant economic considerations, especially under the pressure of spending reduction and the global problem of resource scarcity [102]. The societal dimension appears to be taken for granted [103].

The relationship between sustainability and healthcare is slightly different, aimed at recovering the original nature of the social and human dimension of equitable, inclusive, and sustainable development for all countries and people. Grasping the idea of “what sustainability has to offer to healthcare”, the problem of rare and neglected diseases in which the societal aspects are more apparent should be reframed, incorporating the sustainability principles of equality and inclusiveness as fundamental reference points. Inclusiveness is the core of a strategy that sees the commonalities of orphan drugs and neglected diseases and adopts a vertical equality and high inclusiveness orientation, unlike the more common approaches, as represented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Reframing healthcare approaches in terms of equality and inclusiveness orientations.

In Table 6, it is possible to distinguish four approaches to healthcare on the basis of the kind of equality applied and the degree of inclusiveness:

- An economic approach where equality is considered with reference to the total members of a community without differences in the light of individual conditions. In this approach, inclusiveness is not considered a priority, while attention is focused on approaches and strategies for reducing costs and increasing effectiveness.

- A disease-based approach (I) in which the equality is evaluated with reference to each category of patient or disease, while inclusiveness is not considered as a relevant pillar. In this approach, healthcare management is differentiated on the basis of the patients’ category or disease under evaluation.

- A disease-based approach (II) in which equality is defined without considering the differences between the members of a community, and inclusiveness is considered a key priority of the healthcare system. In such a perspective, health services and processes are ensured to all the members of a community in the same way. This produces a high level of satisfaction among the patients that do not require personalized treatments and low level of satisfaction among the patients with needs that are “different from the average”, as in the case of orphan diseases.

- An equal and inclusive approach where equality is considered in the light of the specific conditions of patients, while inclusiveness represents a key pillar of healthcare. This perspective incorporates the basic principles of sustainability because it underlines the need to recognize the substantial differences between individuals, proposing personalized health treatments to ensure healthy lives and well-being for all.

Evidence of more equal and inclusive approaches to healthcare—also in the case of orphan drugs—is not rare, as the Japanese experience shows. However, as Grabowski [68] (p. 457) suggests, government interventions are necessary to “alter the economic incentives that prevail in this situation”. In this respect, Gericke et al. [69] suggest using the five-step process proposed by the Ad hoc Committee on Health Research as a way to support public research funding to address both the neglected and rare diseases problem.

The proposed change has many implications, such as the need to consider the problem from different points of view and adopt different perspectives. Morel at al. [70] underline the need for a multidisciplinary program able to address several requirements from capacity building to institution strengthening, product development, disease control, and public health.

What should certainly be more deeply discussed is the role that the key actors can play in addressing the problem. As it is commonly framed, the problem appears based on the assumption that it is the policy makers that should define possible measures, while companies are the beneficiaries of such interventions [104,105,106].

By reversing the perspective, we wonder if the pathway towards an equal and inclusive approach to orphan and neglected diseases could be more successful by engaging policy makers as primary actors or better involving companies.

The traditional “institutional” approach, which implies that (health) policy makers should lead the process, appears too constrained by resource scarcity to be successful in ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all. Aware of this problem, we envision a potentially more successful approach in involving companies—especially the big ones—not so much as beneficiaries of incentives but as key players. Companies should look at orphan drugs and neglected diseases not so much as problems to be endured but as opportunities to play a decisive (societal) roles in contributing to solve human problems.

The approach we intend to stimulate is not philanthropic. Rather, it is a change to incorporate societal evaluations in the business models from a sustainability perspective. The societal dimension of sustainability requires more attention, and healthcare is a context in which the sustainability view should be better applied, not only from an economic perspective but also from a social and environmental perspective.

Companies are showing increasing awareness of the necessity for such a change of perspective and are striving to find the way to reconcile their legitimate economic interests with the environmental and societal necessities.

This is a challenge awaiting big pharmaceutical companies, which may lead them to have a stronger impact on society not only as developers of solutions to health problems but also as contributors to the overall well-being of people, especially where this need is more urgent.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we underline that orphan and neglected diseases should not be considered as a health problem to manage but as a part of a complex system that aims to ensure healthy lives and promote universal well-being at all ages [107,108]. In this light, incentives and support for pharmaceutical companies cannot be considered the only way to address the problem but only part of a wider (and shared) strategy.

Therefore, while economic analyses are necessary to ensure the economic performance of companies and sustainability of treatments [109,110,111], traditional evaluation processes based on cost-effectiveness and randomized control to measure the effectiveness of health treatments on the basis of the total amount of resources used and length of health recovery process cannot be dominant [108]. On the other hand, economic incentives mechanisms would never be enough to solve the problem because neither companies nor governments could sustain the huge effort required.

Many practical implications derive from the proposed interpretation. In particular, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) [112] (p. 90) appears to have been expanded to include all relevant social, human, and ethical evaluations [112], going beyond prevalent cost-effectiveness and evidence-based medicine approaches [113] to develop frameworks that extend the boundaries of evaluation practices for more appropriate support for companies and policy decision making [114,115,116].

Adopting a sustainability-based view in healthcare management requires rethinking the pillars on which healthcare strategies and policy makers’ approaches are based to recover the key role of healthcare in ensuring well-being for all. This change implies the inclusion of more variables in the evaluation processes of healthcare [117,118,119,120,121]. New multi- and trans-disciplinary managerial paths in the healthcare domain are to be defined [122,123,124,125,126,127].

Certainly, specific empirical research and further theoretical effort are required to sustain these proposals and to provide concrete indications of potentially successful practical approaches and tools. It would be useful to have direct evidence of companies’ points of view, for example, their current perception of the problem, the way they are interpreting the problems of orphan drugs and neglected diseases, and the potential change in perspective.

This paper represents a call for researchers and practitioners in multi- and transdisciplinary research to develop instruments and models able to support the required change in perspective by integrating competences, knowledge, and information in a shared effort to ensure healthy lives and well-being for all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and M.S.; Methodology, M.S. and F.C.; Project administration, M.S. and M.L.; Supervision, S.B. and M.S.; Visualization, F.C., M.L. and S.Z.; Writing—original draft, M.S., F.C., M.L. and S.Z.; Writing—review & editing, M.S. and F.C.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Robinson, S.; Williams, I.; Dickinson, H.; Freeman, T.; Rumbold, B. Priority-setting and rationing in healthcare: Evidence from the English experience. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2386–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divino, V.; DeKoven, M.; Kleinrock, M.; Wade, R.L.; Kaura, S. Orphan drug expenditures in the United States: A historical and prospective analysis, 2007–18. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1588–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, M.F.; Wilson, D.A.; Kanavos, P.; Ubel, P.; Rovira, J. Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2007, 23, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Neglected Diseases. Available online: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/files/Neglected_Diseases_FAQs.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- Orphanet. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Education_AboutOrphanDrugs.php?lng=EN (accessed on 17 December 2018).

- Eurodis. Available online: https://www.eurordis.org/about-rare-diseases (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Schieppati, A.; Henter, J.I.; Daina, E.; Aperia, A. Why rare diseases are an important medical and social issue. Lancet 2008, 371, 2039–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavandeira, A. Orphan drugs: Legal aspects, current situation. Haemophilia 2002, 8, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, J.K. Rare diseases and orphan drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 61, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joppi, R.; Garattini, S. Orphan drugs, orphan diseases. The first decade of orphan drug legislation in the EU. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 1009–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, R.C.; Batshaw, M.; Dunkle, M.; Gopal-Srivastava, R.; Kaye, E.; Krischer, J.; Merkel, P.A. Clinical research for rare disease: Opportunities, challenges, and solutions. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2009, 96, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haffner, M.E.; Whitley, J.; Moses, M. Two decades of orphan product development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, P. Orphan drugs: The regulatory environment. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, I. Drug discovery in pharmaceutical industry: Productivity challenges and trends. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, C.Y.; Wu, C.W.; Lui, W.Y. Heterotopic pancreas: A difficult diagnosis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1999, 28, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, W.H.; Schwartz, M.S.; Fisher, L.M.; Oppenheimer, M. Acoustic neuroma surgical cost and outcome by hospital volume in California. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitschke, Y.; Rutsch, F. Genetics in arterial calcification: Lessons learned from rare diseases. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2012, 22, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.W.; Senior, T.P. The common problem of rare disease in general practice. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tambuyzer, E. Rare diseases, orphan drugs and their regulation: Questions and misconceptions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Myers, J.A.; Avorn, J. Characteristics of clinical trials to support approval of orphan vs nonorphan drugs for cancer. JAMA 2011, 305, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crompton, H. Mode 2 knowledge production: Evidence from orphan drug networks. Sci. Public Policy 2007, 34, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekings, K.N.; Williams, C.S.; Arrowsmith, J.E. Orphan drug development: An economically viable strategy for biopharma R&D. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mallett, R.; Hagen-Zanker, J.; Slater, R.; Duvendack, M. The benefits and challenges of using systematic reviews in international development research. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Kunz, R.; Kleijnen, J.; Antes, G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, P.S.; Koletsi, D.; Pandis, N. Blinded by PRISMA: Are systematic reviewers focusing on PRISMA and ignoring other guidelines? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, L.I.; Yang, K. Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: Web of Science versus Scopus and Google Scholar. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 2105–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Thomes, C. Implementing discipline-specific searches in EBSCO Discovery Service. New Libr. World 2014, 115, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman-Labadie, O.; Zhou, Y. The US Orphan Drug Act: Rare disease research stimulator or commercial opportunity? Health Policy 2010, 95, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, E.R.; Cockburn, I.M. The hidden cost of low prices: Limited access to new drugs in India. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaughan, M. Pricing Orphan Drugs. Health Aff. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jacob, A.; Tandon, M.; Kumar, D. Orphan drug: Development trends and strategies. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2010, 2, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Gao, J.; Inagaki, Y.; Kokudo, N.; Tang, W. Rare diseases, orphan drugs, and their regulation in Asia: Current status and future perspectives. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2012, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Inspector General. United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Orphan Drug Act Implementation and Impact. 2001. Available online: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-00-00380.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- European Parliament Regulation (EC) no 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the council of 16 December 1999 on Orphan Medicinal Products. 2000. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2000_141_cons-2009-07/reg_2000_141_cons-2009-07_en.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Designated Intractable Disease. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000084783.html (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- Australian Government Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990. Statutory Rules No. 394, 1990 Made under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. 1990. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018C00897 (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- India Drug Manufacturers’ Association. Available online: https://www.idma-assn.org/index.html (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Law & Regulations database of the Republic of China. Takumi Disease Prevention and Medicine Law. 2014. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=L0030003 (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- Ministry of Government Legislation. Pharmaceutical Affairs Act. 2011. Available online: www.moleg.go.kr/FileDownload.mo?flSeq=39483 (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- The Hong Kong Alliance for Rare Diseases, What Is Rare Disease? Available online: http://www.hkard.org/index/about-rare-disease (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- Hemphill, T.A. Extraordinary pricing of orphan drugs: Is it a socially responsible strategy for the US pharmaceutical industry? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, F.M. Pricing, profits, and technological progress in the pharmaceutical industry. J. Econ. Perspect. 1993, 7, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.; Jabon, E.N.; Faseruk, A. Financial and economic implications of orphan drugs the Canadian economy in perspective. J. Financ. Manag. Anal. 2014, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Paulden, M.; Stafinski, T.; Menon, D.; McCabe, C. Value-based reimbursement decisions for orphan drugs: A scoping review and decision framework. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresova, P.; Klimova, B.; Kuca, K. Financial and legislative aspects of drug development of orphan diseases on the European market–a systematic review. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 2562–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A.M. Ethical perspectives on pharmacogenomic profiling in the drug development process. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.; Xie, Z. Challenges in orphan drug development and regulatory policy in China. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minn, M. Development of Orphan Drugs under European Regulatory Incentives and Patent Protection. Eur. J. Health Law 2017, 24, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassal, G.; Kearns, P.; Blanc, P.; Scobie, N.; Heenen, D.; Pearson, A. Orphan Drug Regulation: A missed opportunity for children and adolescents with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 84, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.A.; Tunnage, B.; Yeo, S.T. Drugs for exceptionally rare diseases: Do they deserve special status for funding? QJM 2005, 98, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herder, M. Orphan drug incentives in the pharmacogenomic context: Policy responses in the USA and Canada. J. Law Biosci. 2016, 3, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.T. Incentivizing Orphan Product Development: United States Food and Drug Administration Orphan Incentive Programs. In Rare Diseases Epidemiology: Update and Overview; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Wilson, W.; Palma, A.; Schuurman, A.; Simoens, S. Paying for the Orphan Drug System: Break or bend? Is it time for a new evaluation system for payers in Europe to take account of new rare disease treatments? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammie, T.; Lu, C.Y.; Babar, Z.U.D. Access to orphan drugs: A comprehensive review of legislations, regulations and policies in 35 countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockklausner, C.; Lampert, A.; Hoffmann, G.F.; Ries, M. Novel treatments for rare cancers: The US orphan drug act is delivering—A cross-sectional analysis. Oncologist 2016, 21, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, W.; Moors, E. Exploring emerging technologies using metaphors–a study of orphan drugs and pharmacogenomics. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1915–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, M.; Bellettato, C.; Lampe, C. Orphan Drugs. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assays; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, C.M.; Wilcox, E.; Burgess, M.; Lynd, L.D. Why orphan drug coverage reimbursement decision-making needs patient and public involvement. Health Policy 2015, 119, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavris, M.; Le Cam, Y. Involvement of patient organisations in research and development of orphan drugs for rare diseases in Europe. Mol. Syndromol. 2012, 3, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Han, J. A proposed definition of rare diseases for China: From the perspective of return on investment in new orphan drugs. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrard, S.; Hermans, C. Rare diseases and orphan drugs in Belgium and in the European Union: What is the current situation? Louvain Med 2015, 134, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, S.; Compagni, A.; Reich, M.R. Orphan drug legislation: Lessons for neglected tropical diseases. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2009, 24, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aymé, S.; Kole, A.; Groft, S. Empowerment of patients: Lessons from the rare diseases community. Lancet 2008, 371, 2048–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bastida, J.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Linertová, R.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with rare diseases in Europe. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2016, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linley, W.G.; Hughes, D.A. Societal views on NICE, cancer drugs fund and value-based pricing criteria for prioritising medicines: A cross-sectional survey of 4118 adults in Great Britain. Health Econ. 2013, 22, 948–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, C.; Stafinski, T.; Menon, D. Is it time to revisit orphan drug policies? BMJ 2010, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, H.G. Increasing R&D incentives for neglected diseases: Lessons from the Orphan Drug Act. International public goods and transfer of technology under a globalized intellectual property regime. In International Public Goods and Transfer of Technology Under a Globalized Intellectual Property Regime; Maskus, K., Reichman, J., Eds.; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 457–480. [Google Scholar]

- Gericke, C.A.; Riesberg, A.; Busse, R. Ethical issues in funding orphan drug research and development. J. Med. Ethics 2005, 31, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, C.M.; Serruya, S.J.; Penna, G.O.; Guimarães, R. Co-authorship network analysis: A powerful tool for strategic planning of research, development and capacity building programs on neglected diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, M.; Toumi, M. Access to orphan drugs in Europe: Current and future issues. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M.M.; Farag-El-Massah, S.; Xu, K.; Coté, T.R. Emergence of orphan drugs in the United States: A quantitative assessment of the first 25 years. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenberg, J.P.; Ault, S.K. Neglected diseases of neglected populations: Thinking to reshape the determinants of health in Latin America and the Caribbean. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, A.; Mergaert, L.; Fostier, C.; Cleemput, I.; Simoens, S. Issues surrounding orphan disease and orphan drug policies in Europe. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2010, 8, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S.; Dooms, M. How much is the life of a cancer patient worth? A pharmaco-economic perspective. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2011, 36, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, D.; Jennings, B. Ethics and public health: Forging a strong relationship. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leisinger, K.M. The corporate social responsibility of the pharmaceutical industry: Idealism without illusion and realism without resignation. Bus. Ethics Q. 2005, 15, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joppi, R.; Bertele, V.; Garattini, S. Orphan drug development is progressing too slowly. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 61, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wästfelt, M.; Fadeel, B.; Henter, J.I. A journey of hope: Lessons learned from studies on rare diseases and orphan drugs. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 260, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Vazquez, E.; Rodriguez-Monguio, R.; Szeinbach, S.L.; Visaria, J. Incentives for orphan drug research and development in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008, 3, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S. Pricing and reimbursement of orphan drugs: The need for more transparency. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2011, 6, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’sullivan, B.P.; Orenstein, D.M.; Milla, C.E. Pricing for orphan drugs: Will the market bear what society cannot? JAMA 2013, 310, 1343–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouiller, P.; Olliaro, P.; Torreele, E.; Orbinski, J.; Laing, R.; Ford, N. Drug development for neglected diseases: A deficient market and a public-health policy failure. Lancet 2002, 359, 2188–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskrov, G.; Stefanov, R. Post-marketing access to orphan drugs: A critical analysis of health technology assessment and reimbursement decision-making considerations. Orphan Drugs Res. Rev. 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.P.; Felix, A. Are payers treating orphan drugs differently? J. Mark. Access Health Policy 2014, 2, 23513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, D.; Gibson, B.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E. Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2004, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saviano, M.; Caputo, F.; Napoli, B. Addressing the social and economic challenges of Orphan Drugs: A managerial perspective. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nwaka, S.; Ridley, R.G. Science & society: Virtual drug discovery and development for neglected diseases through public–private partnerships. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morel, C.M.; Acharya, T.; Broun, D.; Dangi, A.; Elias, C.; Ganguly, N.K.; Hotez, P.J. Health innovation networks to help developing countries address neglected diseases. Science 2005, 309, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organizations. World Health Statistics 2014. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/features/qa/58/en/ (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research. Neglected Diseases; 2012. Available online: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/files/Neglected_Diseases_FAQs.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2018).

- Sverdrup, H.; Svensson, M.G. Defining the concept of sustainability—A matter of systems thinking and applied systems analysis. In Systems Approaches and their Application; Olsson, M.O., Sjöstedt, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, D.F. Ecosystem approaches to health for a global sustainability agenda. EcoHealth 2012, 9, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M.; Iandolo, F.; Calabrese, M. The viable systems approach and its contribution to the analysis of sustainable business behaviors. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2014, 31, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Grigoroudis, E.; Del Giudice, M.; Della Peruta, M.R.; Sindakis, S. An exploration of contemporary organizational artifacts and routines in a sustainable excellence context. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals. Knowledge Platform. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- McMurray, A. Community Health and Wellness: A Socio-ecological Approach; Elsevier: Chatswood, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, P.; Bennett, S.; Haines, A.; Pang, T.; Bhutta, Z.; Hyder, A.A.; Evans, T. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet 2004, 364, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, R.; Vittori, G. Sustainable Healthcare Architecture; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D.A.; Fitzgerald, L.; Ketley, D. (Eds.) The Sustainability and Spread of Organizational Change: Modernizing Healthcare; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Buffoli, M.; Capolongo, S.; Bottero, M.; Cavagliato, E.; Speranza, S.; Volpatti, L. Sustainable Healthcare: How to assess and improve healthcare structures’ sustainability. Ann Ig 2013, 25, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, M.; Iandolo, F.; Caputo, F.; Sarno, D. From mechanical to cognitive view: The changes of decision making in business environment. In Social Dynamics in a Systems Perspective; Barile, S., Pellicano, M., Polese, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Tronvoll, B.; Barile, S.; Caputo, F. A systems approach to understanding the philosophical foundation of marketing studies. In Social Dynamics in a Systems Perspective; Barile, S., Pellicano, M., Polese, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Saviano, M.; Bassano, C.; Piciocchi, P.; Di Nauta, P.; Lettieri, M. Monitoring Viability and Sustainability in Healthcare Organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Caputo, F.; Mueller, J.; Belyaeva, Z. Competing through consonance: A stakeholder engagement view of corporate relational environment. Sinergie 2018, 36, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.C.; Cattaneo, A.; Bradley, E.; Chunharas, S.; Atun, R.; Abbas, K.M.; Best, A. Rethinking health systems strengthening: Key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27 (Suppl. 4), iv54–iv61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.J. Holism and reductionism as perspectives in medicine and patient care. West. J. Med. 1979, 131, 466–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Capolongo, S.; Bottero, M.C.; Lettieri, E.; Buffoli, M.; Bellagarda, A.; Birocchi, M.; Gola, M. Healthcare sustainability challenge. In Improving Sustainability During Hospital Design and Operation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draborg, E.; Gyrd-Hansen, D.; Poulsen, P.B.; Horder, M. International comparison of the definition and the practical application of health technology assessment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2005, 21, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantivess, S. Social and ethical analysis in health technology assessment. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2014, 97, S81–S86. [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux, P.; Williams-Jones, B. Mapping the integration of social and ethical issues in health technology assessment. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2007, 23, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, A.; Mital, M.; Pisano, P.; Del Giudice, M. E-health and wellbeing monitoring using smart healthcare devices: An empirical investigation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, G.; Yolles, M.; Caputo, F. Decoding the dynamics of value cocreation in consumer tribes: An agency theory approach. Cybern. Syst. 2017, 48, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. What is value in health care? N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeeargue, M. Budget crises, health, and social welfare programmes. BMJ 2010, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Khan, Z.; De Silva, M.; Scuotto, V.; Caputo, F.; Carayannis, E. The microlevel actions undertaken by owner-managers in improving the sustainability practices of cultural and creative small and medium enterprises: A United Kingdom–Italy comparison. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1396–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Carrubbo, L.; Sarno, D. The Influence of Cognitive Dimensions on the Consumer-SME Relationship: A Sustainability-Oriented View. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Barile, S.; Spohrer, J.C.; Caputo, F. A service research contribution to the global challenge of sustainability. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 951–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamey, G.; Shretta, R.; Binka, F.N. The 2030 sustainable development goal for health. BMJ 2014, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saviano, M.; Parida, R.; Caputo, F.; Kumar Datta, S. Health care as a worldwide concern. Insights on the Italian and Indian health care systems and PPPs from a VSA perspective. EuroMed J. Bus. 2014, 9, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Masucci, A.; Napoli, L. Managing value co-creation in pharmacy. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2018, 12, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, F.; Carrubbo, L.; Caputo, F.; Sarno, D. Managing Healthcare Service Ecosystems: Abstracting a Sustainability-Based View from Hospitalization at Home (HaH) Practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.P.; Barile, S.; Caputo, F.; Corrente, M.I.; Grasso, A.; Saviano, M. Salute, farmaci e integratori in una visione sistemica: Vigilanza su prodotti a base di isoflavoni di soia. Rapporto di ricercar; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, J.; Ródenas, F.; Sanjosé, V. Towards a new welfare state: The social sustainability principle and health care strategies. Health Policy 2003, 65, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).