1. Introduction

In modern capitalist consumer democracies, traditional centralized top-down approaches to environmental policy-making have been supplemented, indeed often replaced, by decentralized, flexible, and participatory network approaches. In addition to state agencies, they engage scientific experts, NGOs, market actors, civil society organizations, and a range of other relevant stakeholders [

1,

2,

3]. As these new modes of collaborative governance have become fully mainstreamed, conventional forms of prescriptive, interventionist, top-down environmental politics have become increasingly unpopular and are now actually often perceived as authoritarian. Since the 1990s, in particular, the modern state is expected to play the role of a coordinator and facilitator in eco-politics, but not to unilaterally issue and impose regulations [

4,

5]. Flexible and consensus-seeking forms of environmental governance are commonly presented as more democratic than traditional interventionist approaches. They are said to take into account that governments are no longer the only (nor the most important) political actor and source of authority, that in an increasingly complex world, environmental problems have multifaceted causes and implications that can only be addressed through constructive collaboration of diverse stakeholders [

6], and that contemporary citizens are more determined than ever to move beyond sheer protesting and mobilizing to actually doing, changing, and impacting [

7]. Furthermore, modern environmental governance is also said to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of environmental policy-making [

8]. It is commonly assumed that cooperative, consensual, voluntary approaches help to reduce conflicts of interest and to engage even those actors, which might otherwise oppose environmental policies or obstruct their effective implementation [

9,

10].

Thus, even though very recently—in the wake of right-wing populist movements, parties, and governments, in particular—a certain resurgence of less participatory and often anti-environmental forms of policy-making may signal the emergence of a new post-governance era, environmental governance is, for the time being, a fully mainstreamed, almost hegemonic “mature paradigm” [

11]. Yet, following a phase of considerable optimism during the 1990s and into the new millennium, the proliferation of collaborative modes of environmental governance has also attracted strong criticism. As regards their democratic quality, it has been argued that these forms of environmental governance are neither inclusive nor egalitarian because in most cases governments determine who qualifies as a stakeholder and is admitted into the policy network [

12]. Thus, these modes of decision-making selectively empower only some actors, who do not have a democratic mandate and who can also not be held accountable by the electorate. Furthermore, as governments not only control which actors are allowed to participate but commonly also set the agenda and the rules of engagement, these forms of governance have been described as post-democratic and post-political: They are set up to facilitate collaboration and consensus and, therefore, systematically eclipse all matters of fundamental disagreement and potentially irreconcilable conflict [

13,

14]. They tightly restrict the boundaries of what can be negotiated as well as the terms of negotiation, and issues are framed in ways that only allow for pragmatic and viable solutions that may be implemented within the realm of the currently possible. Hence, participatory forms of governance may contribute to the political representation of diverse social interests and help pacify mounting societal conflicts, yet, rather than genuinely empowering citizens, they often only co-opt them, mobilize them as an additional resource for the legitimation and stabilization of the established order [

15,

16,

17], and thus potentially even reinforce the much-debated erosion of trust in democratic institutions and procedures [

18,

19,

20].

In terms of their ecological problem-solving capacity, it has been noted that, although flexible actor networks, citizen empowerment, stakeholder engagement, the co-production of knowledge, etc. may, at the local and regional level, in particular, help to devise policies which are acceptable to all stakeholders involved [

9,

21,

22], their proliferation has, as yet, not taken modern consumer societies much closer to the great socio-ecological transformation that many scientists and activists say is urgently required, if major social and ecological disasters are to be avoided [

23,

24,

25]. In fact, the environmental and climate crisis continues to become ever more critical—not least, perhaps, because the prevailing forms of decentralized and collaborative governance are explicitly designed not to disrupt the established order and are, therefore, structurally unable to deliver the kind of change that scientists and environmental movements demand. Moreover, in the recent literature, democratic procedures and the modern state’s democratic legitimation imperative are themselves, increasingly, seen as a part of the problem rather than the solution to the multiple sustainability crisis [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Based on the argument that citizens have a “right to competent government” [

30] (p. 140), there are strong demands again for more epistocratic and expertocratic forms of policy-making [

31,

32], and there is a notable new interest in environmental authoritarianism [

33,

34].

Drawing on the distinction between the

democratic performance (ability to deliver to specifically democratic needs) and the

systemic performance (practical problem-solving capacity) of particular forms of government [

35,

36], the prevailing modes of participatory environmental governance may, therefore, be said to be not very satisfactory in either respect. Despite being widely portrayed as constitutive to environmental good governance, these forms of decentralized, participatory policy-making, in fact, seem rather deficient. So why have they, nevertheless, become so prominent? Exactly what is their appeal for modern consumer societies? In what respects are they

good?

These questions may be answered in a number of ways, some of which have already been touched upon. In what follows, we propose that these new modes of environmental governance have become so prominent because they actually correspond very closely to the particular dilemmas, preferences, and needs of contemporary consumer societies—notably the desire to sustain particular lifestyles and understandings of freedom and self-realization, which are known to be socially and ecologically destructive (unsustainable). If measured by the democratic expectations and eco-political demands of the more radical social movements of the past few decades, the performance of these collaborative forms of governance may, indeed, be found wanting. As regards the socio-ecological transformation that scientists say is required to ward off major catastrophes [

24,

25], their potential may not be very promising either. Yet, if assessed from the perspective of these contemporary dilemmas, preferences, and needs, they do actually perform exceptionally well. More specifically, they provide contemporary consumer societies with a practical policy mechanism that helps them to reconcile the widely perceived seriousness and urgency of socio-environmental problems with their ever more visible inability and unwillingness to deviate from their established societal order, patterns of self-realization and logic of development. Put differently, the prevailing collaborative forms of environmental governance are highly effective tools for managing a condition that is widely perceived as pathological, but which (post-)industrial consumer societies neither can nor perhaps really want to cure: the

politics of unsustainability [

37,

38,

39].

Thus, rather than thinking in terms of performance

deficits or performance

gaps [

40], we are suggesting that decentralized and participatory forms of governance may have become so prevalent precisely because they help to avoid a structural transformation of modern societies, while, at the same time, being uniquely suited to the articulation and experience—i.e., the

performance—of genuine commitment to comprehensive socio-ecological change. This unorthodox interpretation of environmental governance and of performance does not seek to make any normative defense of policy approaches that, quite evidently, do not deliver structural socio-ecological change. However, it seeks to shed light on a dimension of eco-politics which neither the mainstream environmental policy literature nor the critical governance literature [

12,

13,

14]—the latter thinking mainly in terms of

insufficiencies and

failures of governance approaches—really touch upon. Trying to spell out what these policy approaches

do deliver and why they are perceived as

good, our line of inquiry makes a positive and significant contribution to the understanding of environmental governance and contemporary eco-politics more generally.

As the notion of performance plays a pivotal role in our analysis of environmental governance, we begin by differentiating various understandings of this concept, drawing particular attention to performance in the sense of

simulative politics [

41]. In order to retain a focus on actual empirical practices,

Section 3 then applies these different understandings of performance to specific examples of environmental governance. This flags up, inter alia, problems and dilemmas that are distinctive of eco-politics in contemporary consumer societies.

Section 4 further explores these dilemmas from a theoretical point of view and elaborates the argument that modern forms of environmental governance, as practices of simulative politics, may be interpreted as closely responding to them. The concluding section reflects on the potentials and limitations of interpreting environmental governance as the

collaborative management of sustained unsustainability.

2. Notions of Performance

There is no shortage of attempts to assess the “performance of participatory and collaborative governance” [

22]. Yet the suggestion that their striking proliferation may usefully be analyzed in terms of performance in the above-mentioned sense and might easily conjure up simplistic, moralizing condemnations of environmental governance as

merely performative rather than substantive, genuinely committed and effective. Some preliminary reflection on different understandings of performance may be helpful to swiftly move beyond such one-dimensional assessments. To begin with, there is the distinction between performance as measuring (a)

fitness for purpose or

ability to deliver to meet expectations and (b) performance in the

theatrical sense, i.e., as presentation, display, or enactment. For the analysis of environmental governance, both these meanings are relevant. In

Figure 1 below, they are coded as Type A and Type B. The first one focuses on the output (effectiveness) of a tool or process in relation to defined expectations, and covers the efficiency of delivery, i.e., the relationship between the required inputs and delivered outputs. As participatory forms of environmental governance are said to deliver to both democratic objectives and in terms of practical solutions to environmental problems, their fitness for purpose—and, conversely, potential performance deficits or performance gaps—can be assessed, as signaled above, for both their

democratic (Type A1) and their

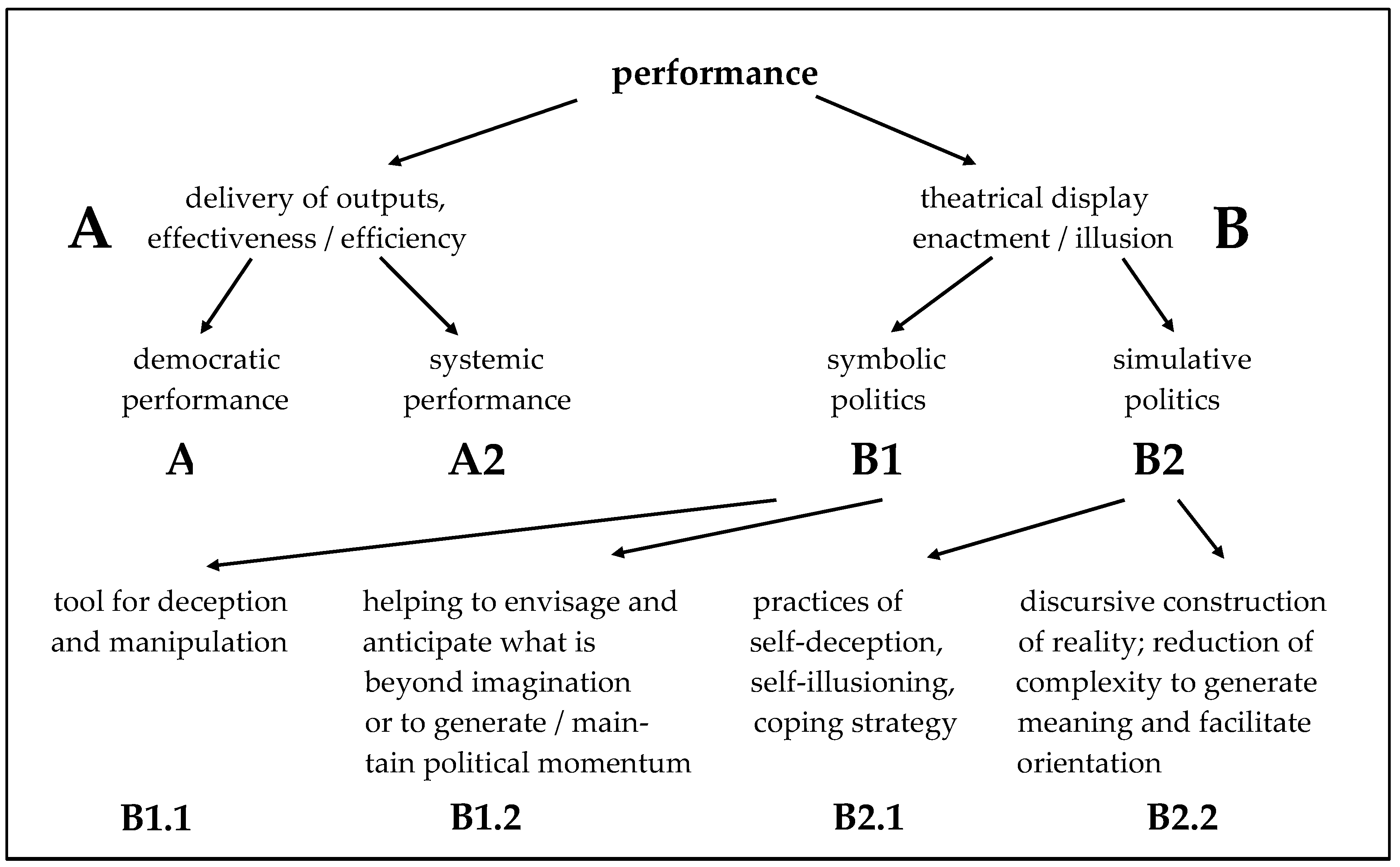

systemic (Type A2) performance.

When it comes to performance in the theatrical sense (Type B), there again are different ways in which the term may be used, and again all of them are applicable to the analysis of environmental governance. Firstly, there are two varieties of what may be referred to as

symbolic politics (B1). One of them entails strategies of

deception and

manipulation, normally by power elites, who are making false promises and take forms of action that are known to be inadequate for their declared purpose but serve the interests of decision-makers or their particular clientele (B1.1). This understanding of performance implies a moral judgement based on the assumption that decision-makers consciously act against the public interest, knowingly take ineffective policy choices, and avoid alternative courses of action which would be more effective and in the public interest. This kind of deceptive action is often described as window-dressing and fake, and criticized as symbolic [

42] as opposed to genuine, authentic, and effective politics.

The second variety of symbolic politics does not have moral overtones but recognizes that in environmental politics, as elsewhere, political goals, visions, and ideals (e.g., to protect a healthy environment or the integrity of eco-systems) are often abstract and intangible and cannot easily, or immediately, be translated into practical policies. Performative action then may help to articulate commitment, to make an abstract goal more imaginable, or to generate and maintain political momentum for its longer-term pursuit (B1.2). Rather than being in any way sinister, manipulative, deceptive, or immoral, this form of symbolic politics is

prefigurative and

anticipatory [

43,

44] and often indispensable in order to forge a political consensus and to encourage cooperation between diverse actors.

In addition to this, and most importantly for the purposes of the present analysis, performative forms of action may also respond to conditions where commitments are serious and authentic but cannot be implemented, be it for structural reasons or because individual actors and societies at large have multiple values and commitments that are all equally genuine but cannot be fulfilled at the same time. In order to distinguish this kind of performative action from symbolic politics (in both its deceptive and the anticipatory variety), it has been conceptualized as

simulative politics (B2) [

41]. In such cases, performative action may help to cope with complexities, paradoxes, and dilemmas that

cannot be resolved but still

must be addressed. As in the case of symbolic politics that helps to visualize the unimaginable (B1.2), this form of performative action is not intended to avoid any more effective and moral—yet inconvenient—alternative. In fact, in either scenario, such alternatives are simply not available. Moreover, in either case, performative action is not based on the unequal social distribution of power. Nevertheless, this latter kind of performance still does entail an element of deception or illusioning. However, in contrast to the malicious deception of citizens by self-interested elites, such practices might suitably be described as voluntary self-deception or self-illusioning (B2.1). In conditions of high societal complexity, in particular, where citizens—and political actors more generally—have to cope with an overload of demands, which may well be incompatible with each other and very disorienting, practices of simulative politics perform a social reality, or construct societal narratives, reducing complexity (B2.2) [

45]. Such practices help individuals—and society at large—to make sense of their paradoxical experience and manage irresolvable dilemmas.

Figure 1 provides an overview of these different notions of performance.

This typology of varieties of performance provides the conceptual tools required to move beyond both 1) the simplistic celebration of new forms of environmental governance as a promising strategy for increasing the legitimacy, efficiency, and effectiveness of environmental policy and 2) their equally simplistic rejection as post-democratic, post-political, and eco-politically ineffective. Of course, there are good examples demonstrating that the now prevalent arrangements of environmental governance actually can deliver effective solutions for certain problems (A1, A2). Moreover, there are in many instances good reasons to criticize the use of stakeholder engagement as window-dressing and a strategic tool for postponing or obstructing policy measures that would be ecologically more effective but are not in the interest of specific stakeholders (B1.1). However, for explaining the particular appeal of these collaborative arrangements and their proliferation in liberal democratic consumer societies, additional, and more sophisticated, tools are required.

Arguably, the reading of performance in the sense of simulative politics (B.2) is particularly helpful in this respect. It has significant potential to reveal something that neither the mainstream perspective nor the analyses by the critical governance literature manage to capture. For, in today’s neoliberal consumer societies, these new forms of environmental governance are, arguably, centrally important practices facilitating the

politics of unsustainability: They allow maximum space for the preservation of the unsustainable, yet apparently non-negotiable, values, freedom, and way of life [

38,

46] while providing optimal opportunities for the articulation and experience of deeply felt socio-ecological values and commitments. Thus, the prevailing forms of environmental governance may be said to deliver in that they address the dilemma that liberal consumer societies are lacking the will and ability to resolve their multiple sustainability crisis, but fully acknowledge that this crisis is more real and urgent than ever before. Governance is

good in that the collaborative management of sustained unsustainability is facilitated. Before further theorizing this dilemma and the politics of unsustainability, we first apply the conceptual lens(es) distinguished here to actual practices of environmental governance. In looking at these empirical cases, the objective is not to provide an in-depth analysis of the respective policy settings and outcomes but to illustrate the analytical potential of the multidimensional concept of performance. In

Section 4 we then return to the theoretical perspective to shed more light on the particular dilemmas and paradoxes that, arguably, are an important parameter in explaining the appeal and striking proliferation of these forms of environmental governance.

3. Practices of Performative Environmental Governance

Prominent examples demonstrating how modern environmental governance has moved, vertically and horizontally, beyond conventional state-centered government are (a) international climate summits such as the United Nations Climate Change Conferences, (b) the involvement of market actors into environmental policy-making, and (c) the official recognition of civil society initiatives and niche movements as pioneers, drivers, and laboratories of societal change towards sustainability. Referring to different levels of policy-making, these examples may be used to illustrate how contemporary forms of environmental governance can be investigated through the lens of performance. An exhaustive analysis cannot be offered within the confines of this article. Yet it is certainly possible to show how, in all these cases, the different dimensions of performance conceptualized above are applicable. They may be distinguished analytically but are in practice tightly interconnected.

Table 1 below selectively summarizes some key aspects.

(a) International climate politics under the roof of the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is one of the best-known examples of international environmental governance. In terms of performance as the delivery of policy outputs (Type A), the annual Conferences of Parties (COPs) seem promising because these gatherings are prepared and attended by international leaders, scientific experts, climate activists, and a wide range of non-governmental organizations, all protesting their commitment to fast, coordinated, and effective climate action [

47,

48]. At the same time, however, such summits may also be portrayed as performance in the theatrical sense (Type B). They may suitably be described as symbolic politics (B1), firstly, because the 1.5 or 2 °C limit itself has acquired the status of a political symbol that helps to visualize something that is highly abstract and well beyond human capacities of perception: a relatively safe level of change in global average temperatures compared to pre-industrial levels. Secondly, the regular climate summits also help to maintain the international diplomatic infrastructure and to uphold the political momentum even in periods when factual progress is difficult to achieve. In both these respects, international climate summitry is symbolic politics in the prefigurative and mobilizing sense (B1.2) [

49]. Yet it may also be understood as symbolic politics in the deceptive and manipulative sense (B1.1) [

50]. In fact, UN climate summits have been criticized as professionally staged media events and costly and eco-politically ineffective—in terms of the CO

2 emissions they cause, even damaging—public relations exercises, providing international lobby groups with an exceptional opportunity to exert their influence and world leaders with a stage to make big promises which they neither can, nor perhaps even want to, fulfill [

51].

The 2015 Paris Agreement, for example, that fails to specify any legally binding policy measures but was still presented to the world as a major climate-political achievement [

52], may be seen to corroborate the view that international climate summitry is, more than anything, a strategic tool that economic and political elites use to mollify the concerns of the international public whilst closely protecting their respective interests [

53]. Yet this interpretation in terms of ruthless power elites conspiring against helpless populations and the planet at large fails to take into account that the negotiating parties may well be very genuinely committed to reaching an effective agreement but find themselves caught up in the dilemma that it is extremely difficult to translate the abstract 2 °C target into nationally acceptable and internationally interlocking action plans [

54]. Furthermore, all national governments have to accommodate a range of different state goals that are often mutually incommensurable already at the national not to mention international or global level. Put differently, national governments are subject to—and powerfully blocked by—the incompatibility of a range of imperatives that are all equally categorical.

The interpretation of internal climate summitry in terms of simulative politics (B2) takes account of these dilemmas. From this perspective, these high profile events may be understood as an opportunity for policy-makers to articulate their genuine and serious commitment to the goal of environmental sustainability and provide evidence that they are pursuing this goal at the highest possible level and in cooperation with the widest possible range of stakeholders—while avoiding, or at least postponing, any detrimental implications for their other, equally serious commitments. The same applies to the wide range of other actors attending such summits, all of whom share the desire to demonstrate and experience their environmental values but also have to accommodate other commitments. It even extends to those non-participants who join into celebrating outcomes such as the Paris Treaty as a major eco-political achievement—relieved that a solution has been found that does not directly affect their personal value preferences and lifestyle choices (B2.1). Seen through the lens of simulative politics, their intentions do not appear immoral or malicious. However, these actors and audiences are experiencing inescapable dilemmas and have to find ways in which they might cope with unmanageable paradoxes (B2.2).

(b) Close co-operation with market actors, ranging from large international corporations right down to individual consumers, is another pillar of modern environmental governance. Traditionally, the interests of these actors were seen as diametrically opposed to those of environmentalists, and big companies as well as consumers were regarded as primary targets of state-centered regulatory politics. More recently, however, major corporations have been working closely with state agencies, expert bodies, and environmental NGOs to reduce the environmental impact of production, distribution, and consumption processes. State regulation has been supplemented or even replaced by schemes of voluntary self-monitoring. Initiatives such as Global Compact under the roof of the UN or the Eco Management and Audition Scheme of the European Union foster the ethical self-management of companies. Corporate Environmental Responsibility (CER) has become a prominent part of the mission statements of all major firms and of their brand-management and public relations efforts [

55]. At the other end of the market, these new corporate efforts are complemented by a shift in consumer behavior, in particular segments, towards environmentally and ethically oriented product choices [

56,

57,

58].

Looking from the perspective of problem-solving capacity, the engagement of market actors into collaborative networks of environmental governance may convey considerable hope: Self-monitoring schemes, Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility schemes, and the related reporting requirements may help companies to reorient their unsustainable practices and enable other stakeholders to assess the environmental credentials of companies. They potentially empower consumers to exert some market pressure; businesses, in turn, can use their CER and CSR efforts to strengthen their relative position vis-à-vis less green competitors; and NGOs can provide evidence that, in addition to mere protesting, they also engage in devising constructive solutions to eco-political challenges [

59,

60]. Overall, the engagement of market actors in networks of collaborative governance may, therefore, be an effective tool for reconfiguring the established logic of consumer capitalism.

The lens of symbolic politics, in contrast, suggests that the involvement of market actors performs mainly in the sense of facilitating corporate strategies of deception. On the one hand, the enrolment of diverse market actors may, of course, be symbolic in the prefigurative sense: It may help to envisage the goal of a comprehensive transformation of society, generate momentum for this project, and subtly create the conditions for its success [

61]. On the other hand, however, the inclusion of market actors into networks of governance not only entails the risk of regulatory capture [

62], i.e., of those whose behavior is to be regulated gaining major influence on, or even control over, those who are supposed to set the rules. However, in practice, CER and CSR schemes are often merely a tool companies use to greenwash their public image [

63,

64]. As a marketing strategy, they are designed to further increase sales and consumption; thus, they sustain rather than reconfigure the destructive principles of capital accumulation, social inequality, commodification, and so forth [

65].

Green consumerism, in turn, is symbolic in that it tends to be selective and focus on very particular products. This may, of course, anticipate and signal commitment to a much more thoroughgoing transformation of established consumption practices [

66], but more often it is a means of articulating a specific self-understanding, social status, or lifestyle. Most importantly, green consumerism is rarely about consuming less or even abandoning the shopping and consumer culture [

67,

68]. Instead, neoliberal governments, while trying to offload their eco-political obligations to “responsible consumers” [

69,

70,

71], see green consumerism as a means to open up new markets and stimulate

green growth [

72]. Supposedly responsible, green consumer choices may well be ecologically counter-productive, for example, if they merely ennoble ecologically damaging practices (e.g., voluntary carbon surcharge for air tickets) or if environmentalism incentivizes additional purchases (e.g., supposedly eco-friendly e-bikes) or premature product replacement (e.g., slightly cleaner diesel cars) [

73,

74]. Thus, just as CER and CSR never unhinge the logic of capitalism, green consumerism rarely suspends the logic of mass consumption and resource overuse [

75,

76]. Hence, the assertion that consumer pressure can make a significant and lasting contribution to a socio-ecological sustainability transformation remains questionable.

The lens of simulative politics, however, adds a further layer to the understanding of both corporate environmentalism and green consumerism. More specifically, it suggests that these two dimensions of modern environmental governance have become important because they enable businesses and consumers alike to manage the diverse and often conflicting pressures with which they find themselves confronted. CER and CSR schemes help corporations to respond to civil society critiques, innovation pressures, government agendas, and shareholder interests at the same time by offering multi-layered narratives that each stakeholder group may read selectively from their particular perspective. Green consumerism helps modern citizens to hold on to their established patterns of self-realization, further pursue their lifestyle preferences, and articulate their individual identities [

77,

78]. More specifically, it allows them to act and experience themselves not only as individualized consumers but also as socially and ecologically oriented and responsible citizens [

56]. Thus, corporate environmentalism and green consumerism both respond to the problems of highly differentiated selves and societies. They perform something theatrically that in conditions of increasing complexity and accelerated change can no longer be achieved by other means: They bridge the “yawning gap between the right of self-assertion and the capacity to control the social setting which render such self-assertion feasible or unrealistic” [

79] (p. 38).

(c) Complementing the engagement of market actors, civil society initiatives and local niche movements, too, have acquired an important role in modern environmental governance. They have been recognized as actors which, as

pioneers of change, might make a substantial contribution to the great transformation to sustainability [

61]. Initiatives such as renewable energy cooperatives, community-supported agriculture projects, repair cafés, alternative housing collectives, food- and tool-sharing platforms, or local currencies flourish in a realm beyond both the market and the state and can function as laboratories for experimental social practices and societal change. There is an expectation that they can substantially increase the democratic performance and boost the problem-solving capacity of local communities and society at large [

7,

80]. Beyond their effects in the immediate present, they also perform in the sense that they symbolically anticipate a radically different society. Indeed, this prefigurative aspect is central to the transformative potential of civil society-driven initiatives. As the hegemony of market-liberal thinking renders it ever more difficult to even envisage any alternative to the consumer capitalist order of unsustainability, these niche movements help not only to imagine but actually experience alternative practices and socio-ecological relations [

81,

82,

83].

A number of observers have pointed out, however, that practitioners within niche movements often remain rather ambivalent about really abandoning the established practices and lifestyles of unsustainability. In fact, activists often refrain from adopting a radically critical or antagonist stance towards the existing political-economic regime and conceive of their alternative practices not as a radical political project but the playful effort

to do something good [

7,

84]. This raises questions about the extent to which these initiatives and niche movements can really be regarded as pioneers of a radical societal transformation. In fact, studies trying to compare the environmental impact of different social milieus have revealed that individuals belonging to the well-educated, post-materialist, creative milieus—which provide an important reservoir for alternative niche movements [

85]—often remain strongly attached to mobility practices, communication technologies, domestic accommodation and living patterns, and so forth, which are closely associated with the “imperial mode of living” [

86] and the culture of “externalization” [

87] prevailing in the societal mainstream [

88,

89]. Put differently, the engagement in niche movements and the experience of alternative practices do not necessarily signal much commitment to a profound transformation of the prevailing order of unsustainability, but may—in a rather apolitical and consumerist manner—simply be an ingredient of a particular personal image or lifestyle [

57,

77].

From a traditional critical perspective, such ambivalence may then be read as inconsistency, false posturing, fake, and performance, signaling dishonesty or a lack of genuine eco-social commitment that may be morally condemned (symbolic politics). Yet, if conceptualized in terms of simulative politics, this simultaneity of seemingly incompatible practices and value-orientations may be interpreted as a performative strategy to deal with complexities—to cope with the paradoxes and make sense of the irresolvable contradictions of contemporary consumer societies. From this perspective, the engagement in niche movements might be interpreted as the attempt of individuals to recuperate an autonomous space for expressing their environmental and democratic values [

45,

90]. In these arenas they can experience some degree of sovereignty with regard to everyday needs such as food, energy, or clothing, whilst fully acknowledging that in other respects their everyday conduct may be much less self-determined—and sustainable. Thus, participation in a food cooperative or alternative housing project may well articulate a serious pledge to a sustainable way of living [

7,

86,

91]. However, rather than anticipating a full and consistent transformation of a personal—and then societal—way of life, it may then be read as a performative and experiential strategy for the management of inescapable dilemmas and irresolvable contradictions.

4. Explaining the Appeal of Participatory Governance

The above illustrations are only indicative, but they clearly demonstrate how the multi-layered concept of performance developed in

Section 2 facilitates a much more nuanced interpretation of actual practices of environmental governance than is offered in much of the mainstream literature. Yet, to understand the particular appeal and explain the striking proliferation of these new practices, further analysis is required of the distinctive condition and dilemmas of eco-politics in liberal consumer democracies to which practices of simulative politics, in particular, seem to respond. More systematic attention is needed to the multiple problems of contemporary eco-politics and to the above assertion that contemporary consumer societies lack the political will and ability to resolve their multiple sustainability crisis.

This failure of contemporary consumer societies to achieve a socio-ecological transformation is commonly explained by referring to the institutionalized interests and overwhelming power of economic elites who effectively block any substantial deviation from the established order and pattern of development and who systematically deny citizens their right to self-determination and a good life in conditions of social justice and ecological integrity [

12,

92,

93]. This argument captures part of the truth but ignores the eco-political predicament of liberal consumer democracies—which may, ultimately, be a more significant cause of both the difficulty to achieve structural socio-ecological change and the striking proliferation of governance arrangements. As signaled above, contemporary consumer democracies are caught up in the trilemma that (a) despite the wealth of scientific information, the normative foundations for transformative action are becoming ever more uncertain and unreliable; (b) despite unprecedented levels of environmental awareness and commitment, there is neither a political actor who could effectively drive and coordinate transformative action, nor a promising political strategy; and (c) in contemporary consumer societies prevailing notions of freedom, identity, self-realization, and a good life are ever more incompatible with ideals of environmental integrity, social justice, and democracy—but are regarded, nevertheless, as non-negotiable and defended with great determination.

(a) For a long time, environmental movements had assumed that environmental problems and the need for transformative action are essentially self-evident and that campaigns of public information and education would, eventually, generate the support required for effective action against unsustainability. They tended to disregard that there is a major difference between empirical

facts and social

concerns [

94,

95] and that environmental politics is primarily about the latter rather than the former [

96,

97,

98]. Yet, as processes of modernization rendered contemporary societies ever more complex, giving rise to an ever larger number of perspectives onto reality and to competing views of what ought to be sustained, for whom, for which reasons, and so forth, the normative foundations of environmental politics became increasingly uncertain. Moreover, the growing wealth of scientific knowledge and information, unexpectedly, triggered disorientation at least as much as they were politically mobilizing and enabling [

78]. In addition, the acceleration of societal change, the unpredictability of societal development, and the complexity of international relations have a paralyzing effect. When neoliberals and right-wing populists then started to amplify alleged scientific disagreement, for example, about anthropogenic climate change [

99], discredited the public media as

fake news, and replaced public deliberation and rational argument by fabricated fears and

alternative facts, it became virtually impossible to achieve and maintain agreement about eco-political problems, priorities, objectives, and strategies.

(b) As regards the primary driver and political strategy for the socio-ecological transformation of contemporary societies, environmental movements, whilst strongly relying on the state to provide and enforce a suitable framework of laws, had always been skeptical of the state, which they thought was pre-occupied, more than anything, with the reproduction of power and, beyond that, too closely entangled with business interests. Hence, environmentalists preferred to rely, instead, on civil society’s capacity for self-organization and believed that the thorough democratization of every dimension of societal affairs would be a promising strategy to achieve social justice and equality, secure the integrity of the natural environment, and guarantee a good life for all. Yet, in increasingly complex societies, democratic procedures proved, in many respects, to be not conducive to the attainment of ecological goals because, for example, they are very long-winded, focused on short-term electoral returns, based on the principle of compromise, and always rather limited in terms of their geographical reach [

100]. Moreover, civil society and the ethos of engagement and self-responsibility were increasingly captured by neoliberals and their activating state, which sought to devolve former state responsibilities. Furthermore, in line with a notable decline of public confidence in democracy, more generally [

18,

19], environmentalists, too, began to suspect that there might, in fact, be an underlying “complicity” between democracy and unsustainability [

29,

101] (p. 985): After all, the demands of ever larger parts of (international) society for a good life and their fair share of societal wealth are, and have always been, a powerful driver of ever more economic growth and socio-ecological exploitation [

27,

28]. And with right-wing populist movements powerfully demanding—bottom up—less stringent environmental regulations and laws [

102], civil society and democratic approaches seem to be becoming even less suitable for a profound socio-ecological transformation. Yet, an alternative actor and more promising strategy is not easily in sight. Paternalistic

nudging approaches [

103], for example, or growth-oriented

Green New Deal scenarios [

104,

105] each have their own problems attached to them.

(c) In terms of their prevailing notions of freedom, self-realization, and a fulfilling life, modern consumer societies have acquired value preferences, aspirations and lifestyles that are categorically incompatible with the principles of sustainability. In fact, with the pluralization and flexibilization of traditional notions of subjectivity and identity, with consumerism having emerged as the primary mode of self-realization and self-expression, with the massive geographical expansion of individual lifeworlds (mobility, product sourcing, and waste disposal), and the steady acceleration of innovation and consumption cycles, unsustainability has in many ways become a constitutive principle of modern identity, lifestyles, and society. It is ever more difficult to conceptualize it as an unintended, undesirable, and potentially amendable side effect. Instead, the subjectivities and patterns of self-realization of the global consumer elites, in particular, are—in the era of flexibility, innovation, and planned obsolescence—unsustainable by intention and design [

29,

90]. Despite all narratives of sustainability and a socio-ecological transformation, contemporary individuals and societies at large are incrementally emancipating themselves from established social and ecological imperatives (e.g., social equality, solidarity and redistribution, protection of natural habitats, bio-diversity, and human rights agendas), which from the perspective of contemporary value preferences, ambitions and necessities seem unacceptably restrictive [

46,

100]. Instead, contemporary consumer societies are firmly committed to value preferences, lifestyles, and social aspirations, which are widely known and accepted to be socially and ecologically destructive [

86,

87] but are still adamantly defended.

Therefore, contemporary consumer societies are confronted with the dilemma that, in the new geological era of the Anthropocene, radical transformative action, “planetary management” [

23], and “earth systems governance” [

24,

106] may seem more urgently required than ever, but the normative foundations for such an agenda are more uncertain than ever, there is no primary actor nor a promising political strategy for any significant transformation, and the prevailing and sacrosanct notions of freedom, self-determination, and self-realization are firmly based on the principle of sustained unsustainability.

Exactly this is, arguably, where modern forms of governance as a decentralized and collaborative mode of addressing environmental concerns come in, and performance as a form of action that delivers to the specific needs of modern societies. In this particular constellation, contemporary forms of environmental governance are good with regard to all three dimensions of the eco-political disability of modern societies: With the absence of reliable eco-political norms, they deal by delegating the issue to self-regulating entities, responsible consumers, and their voluntary self-commitment, thereby alleviating the problems governments and policy-makers have with defining, politically legitimating, and enforcing particular standards and laws. They address the lack of a promising actor and strategy for transformative change by setting up new—and supposedly capable—policy networks and charging them with the task to negotiate and implement an inclusive social contract for sustainability. As regards the value preferences of contemporary individuals and consumer society at large, these new forms of governance are good in that they allow for the articulation of eco-social commitments and for the desire to maintain the established principles of unsustainability. They provide arenas for the experience of eco-political agency, efficacy, and integrity, but are voluntary and non-committing and can be disposed of as and when required. In none of these respects, modern arrangements of environmental governance resolve the problems in the sense of effecting structural change to the prevailing socio-metabolic regime, but in all of them, they address them and respond to the particular needs of modern consumer societies. They are a performative response to the multi-dimensional disability of contemporary eco-politics and to the unwillingness of liberal consumer societies to depart from their established culture of sustainability. In exactly this sense, they are a societal practice for the collaborative management of sustained unsustainability.

5. Conclusions

In the existing literature, the proliferation of decentralized and participatory forms of environmental governance has been investigated, and their performance assessed, from a number of different perspectives. In this article we have taken a socio-theoretically informed approach and have found that interpreting modern environmental governance as performance in the sense of simulative politics makes a major contribution to understanding these policy arrangements. Further research is required to empirically apply the conceptual framework developed here much more systematically. Yet it has already become clearly visible how a multi-layered understanding of performance facilitates an analysis that is more nuanced than both the celebration of these decentralized, collaborative practices as a promising strategy for the great transformation to sustainability and the critique of environmental governance as being

merely performative rather than genuinely committed and effective. Blühdorn has argued that the concept of sustainability, which retains its lead position in public discourse on eco-politics and -policy even though very few observers still regard it as a promising leitmotiv for the great transformation of modern consumer societies, is so successful not although but precisely because it is highly unlikely to disrupt the order of consumer capitalism [

107]. Following the same line of thought, we have argued here that decentralized and participatory forms of governance proliferate not although but exactly because they do not perform in terms of a structural transformation of modern societies. We have suggested that the governance approach to environmental policy-making has become so prominent because it corresponds very closely to the particular concerns, preferences, and dilemmas of contemporary consumer democracies. From this perspective, environmental governance is not “the totality of instruments and mechanisms available to collectively steer” [

2] (p. 8) their socio-ecological transformation but to collaboratively manage their politics of unsustainability.

More traditional analyses in terms of performance have either analyzed environmental governance as effective and efficient tools for resolving sustainability problems, or as deceptive strategies of elites that urgently need to be replaced by the authentic kind of eco-politics which scientists, activists, and eco-movements demand—and supposedly want. While we acknowledge that these approaches have a substantive contribution to make, we argue that in contemporary consumer societies things are more complex than these approaches suggest. The curious proliferation—and lasting significance—of environmental governance can be explained much more plausibly by adding the perspective of simulative politics: Practices of environmental governance provide arenas in which the commitment to eco-political values and transformative change can be articulated, and in which actors can present and experience themselves as being fully committed to social and ecological sustainability, whilst at the same time also holding on to, and adamantly defending, their socially and ecologically destructive consumer preferences, habits, and lifestyles.

Two predictable objections to this interpretation of environmental governance concern, firstly, the empirical evidence supporting its claims and, secondly, its political use-value, be it for official policy-makers or social movement activists. As regards the empirical evidence, we are making no claim to offering a full and exhaustive account, of current forms of environmental governance. Drawing on sociological and eco-political theory, we are offering a conceptual framework for analyzing contemporary practices of governance and for explaining their appeal and proliferation. Its objective is to help make sense of seemingly inefficient eco-political practices and their proliferation. The suggested framework can be assessed on the basis of its theoretical consistency, practical applicability, and explanatory power—as demonstrated in the discussion of various examples. However, it is not possible to support our hypotheses with empirical evidence in the positivist sense—not least because this interpretative framework operates at the macro-theoretical level of overall societal development rather than that of particular actors and their conscious strategic actions.

As regards the suggested framework’s actual use-value, this is by no means confined to the theoretical and explanatory dimension. In the first instance, its emphasis is, indeed, on better understanding the eco-political conduct of liberal consumer societies. At this stage, it does not offer suggestions for alternative policy approaches which might perform better—not least because, it remains itself caught up in the normative dilemma it diagnoses. Accordingly, it confines itself to investigating what modern consumer societies conceptualize as good environmental governance, and why they might be doing so. Policy-makers and activists may well find this unsatisfactory and ask for more: The former rarely appreciate academic research that does not provide them with practical policy recommendations, and the latter may complain that the analysis undertaken here not only undermines the efforts of those who seek to unmask what they see as merely performative strategies of the elites, but actually subjects these well-intentioned critics to the meta-critique that their discourse, too, may have to be read as a performance of particular values and commitments, which, ultimately, itself contributes to the collaborative management of unsustainability. This, in turn, then raises the larger question whether in modern consumer societies the vicious circle of simulation can be transcended at all, and whether the analysis presented here may, ultimately, be little more than the socio-theoretical equivalent of the neoliberal principle of TINA (there is no alternative): a social-theoretical justification of the prevailing politics of unsustainability.

This is explicitly not what this article seeks to deliver! Our analysis is far from being indifferent to the social and ecological disasters implied in the politics of sustained unsustainability. We firmly hold on to the belief that a radical socio-ecological transformation is urgently required. For exactly this reason, we are keen to demonstrate that the limitations of modern forms of environmental governance cannot be overcome by involving yet another stakeholder or adding yet another layer of deliberation. Instead, the inability to achieve the great transformation must be traced back to the particular condition of modern societies in which unsustainability has metamorphosed from an unforeseen side effect into a constitutive principle of contemporary subjectivities, lifestyles, and society at large. The mounting pressure for quick and pragmatic policy suggestions—which necessarily have to discount this aspect—is itself a constitutive element of the politics of unsustainability. Even though the analysis presented here may, at first sight, appear politically unconstructive or even disabling, the critical deconstruction of the prevailing narratives and practices contributing to the collaborative management of sustained unsustainability is, quite clearly, an essential and indispensable step for any socio-ecological transformation of modern liberal consumer democracies.