Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Otis, K.L.; Huebner, E.S.; Hills, K.J. Origins of Early Adolescents’ Hope: Personality, Parental Attachment, and Stressful Life Events. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 31, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez, M.P.; Teva, I.; Buela-Casal, G. Influencia de variables sociodemográficas sobre los estilos de afrontamiento, el estrés social y la búsqueda de sensaciones sexuales en adolescentes [Influence of sociodemographic variables on coping styles, social stress, and sexual sensation seeking in Adolescent]. Psicothema 2009, 21, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- Espada, J.P.; Gonzálvez, M.T.; Orgilés, M.; Lloret, D.; Guillén-Riquelme, A. Meta-analysis of the Effectiveness of School Substance Abuse Prevention Programs in Spain. Psicothema 2015, 27, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Parra, A.; Sánchez-Queija, I. Consumo de sustancias durante la adolescencia: Trayectorias evolutivas y consecuencias para el ajuste psicológico [Consumption of substances during adolescence: Evolutionary trajectories and consequences for psychological adjustment]. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2008, 8, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Encuesta Sobre Uso de Drogas en Estudiantes de Enseñanzas Secundarias (ESTUDES) 2014/2015 [Survey on Drug Use in Secondary Education Students (ESTUDES) 2014/2015]; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, España, 2016.

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Encuesta Sobre Alcohol y Drogas en España (EDADES) 2017/2018 [Survey on Alcohol and Drugs in Spain (EDADES) 2017/2018]; Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social: Madrid, España, 2018.

- Bushman, B.J.; Newman, K.; Calvert, S.L.; Downey, G.; Dredze, M.; Gottfredson, M.; Jablonski, N.G.; Masten, A.S.; Morrill, C.; Neill, D.B.; et al. Youth violence: What we know and what we need to know. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Health for the World’s Adolescents. A Second Chance in the Second Decade; World Health Organization: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Calmaestra, J.; Escorial, A.; García, P.; del Moral, C.; Perazzo, C.; Ubrich, T. Yo a Eso no Juego: Bullying y Ciberbullying en la Infancia [I Do Not Play That: Bullying and Cyberbullying in Childhood]; Save the Children: Madrid, España, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, E.; Jiménez, T.I.; Moreno, D. Aggressive behavior in adolescence as a predictor of personal, family, and school adjustment problems. Psicothema 2018, 30, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, B.; Portela, I.; López, E.; Domínguez, V. Violencia verbal en el alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria [Verbal violence in the students of Compulsory Secondary Education]. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. 2018, 8, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Navarrete, R.; Horigian, V.E.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Verdeja, R.E.; Alonso, E.; Feaster, D.J.; Fernández-Mondragón, J.; Berlanga, C.; Sánchez-Huesca, R.; Lima-Rodríguez, C.; et al. Intervención de incremento motivacional en centros ambulatorios para las adicciones: Un ensayo aleatorizado multi-céntrico [Motivational enhancement treatment in outpatient addiction centers: A multisite randomized trial]. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, K.; Shipley, L.; Stewart, D.G. Motivation and substance use outcomes among adolescents in a school-based intervention. Addict. Behav. 2016, 53, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapié, C.; Corredor, S.; Barbosa, C.; Méndez, M.; Muñoz, L. Evaluación de un producto sonoro en las creencias referidas al consumo de alcohol en jóvenes universitarios [Evaluation of a sound product in beliefs related to alcohol consumption in university students]. Horizontes Pedagógicos 2013, 15, 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, C.; Del Moral, G.; Martínez, B.; John, B.; Musitu, G. El patrón de consumo de alcohol en adultos desde la perspectiva de los adolescentes [Adult pattern of alcohol use as perceived by adolescents]. Gac. Sanit. 2016, 30, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, L.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Casanova, J.R.; Gázquez, J.J.; Molero, M.M. Alcohol expectancy-adolescent questionnaire (AEQ-AB): Validation for Portuguese college students. Health Addict. 2018, 18, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Martos, A.; Cardila, F.; Barragán, A.B.; Carrión, J.J.; Garzón, A.; Mercader, I. Adaptación española del Cuestionario de Expectativas del Alcohol en adolescentes [Spanish adaptation of the Alcohol Expectancy-Adolescent Questionnaire, Brief]. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. 2015, 5, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Gázquez, J.J. Expectations and Sensation-Seeking as predictors of Binge Drinking in adolescents. Ann. Psicol. 2019, 35, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, R.F.; Hoff, R.A.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Patock-Peckhan, J.A.; Potenza, M.N. Impulsivity, Sensation-Seeking, and Part-Time Job Status in Relation to Substance Use and Gambling in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, A.; Barker, E.; Koot, H.; Maughan, B. The Role of Contextual Risk, Impulsivity, and Parental Knowledge in the Development of Adolescent Antisocial Behavior. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmberg, M.; Kleinjan, M.; Overbeek, G.; Vermulst, A.A.; Lammers, J.; Engels, R. Are There Reciprocal Relationships between Substance Use Risk Personality Profiles and Alcohol or Tobacco Use in Early Adolescence? Addict. Behav. 2013, 38, 2851–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcázar, M.A.; Verdejo, A.; Bouso, J.C.; Ortega, J. Búsqueda de sensaciones y conducta antisocial [Sensation seeking and antisocial behaviour]. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica 2015, 25, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, P.A.; Pérez-Luco, R.X.; Wenger, L.S.; Salvo, S.I.; Chesta, S.A. Personality and offense severity in adolescents with persistent antisocial behavior. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud 2018, 9, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Molero, M.M.; Cardila, F.; Martos, A.; Barragán, A.B.; Garzón, A.; Carrión, J.J.; Mercader, I. Impulsividad y consumo de alcohol y tabaco en adolescentes [Adolescent impulsiveness and use of alcohol and tobacco]. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2015, 5, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, N.E.; Ryan, S.R.; Bray, B.C.; Mathias, C.W.; Acheson, A.; Dougherty, D.M. Altered Developmental Trajectories for Impulsivity and Sensation Seeking among Adolescent Substance Users. Addict. Behav. 2016, 60, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, M.C.; Arco, J.L.; Fernández-Martín, F.D. La relación entre la impulsividad cognitiva (R-I) y el maltrato entre iguales o “bullying” en educación primaria [The relationship between cognitive impulsivity (R-I) and peer abuse or “bullying” in primary education]. Anál. Modif. Conducta 2005, 31, 359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Simón, M.M. Búsqueda de sensaciones e impulsividad como predictores de la agresión en adolescentes [Sensation seeking and impulsivity as predictors of aggression in adolescents]. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2016, 8, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Carrión, J.J.; Mercader, I.; Gázquez, J.J. Sensation-Seeking and Impulsivity as Predictors of Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Carrión, J.J.; Luque, A.; Molero, M.M. Interpersonal Value Profiles and Analysis to Adolescent Behavior and Social Attitudes. Rev. Psicodidact. 2015, 20, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. A meta-analysis of the predictors of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization. Psychol. Sch. 2016, 53, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero, M.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Luque, A.; Martos, A.; Barragán, A.B.; Simón, M.M. Interpersonal Values and Academic Performance Related to Delinquent Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro, J.I.; Zurita, F.; Castro, M.; Martínez, A.; García, S. Relación entre consumo de tabaco y alcohol y el autoconcepto en adolescentes españoles [The relationship between consumption of tobacco and alcohol and self-concept in Spanish adolescents]. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2016, 27, 533–550. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, F.M. Relaciones entre afrontamiento del estrés cotidiano, autoconcepto, habilidades sociales e inteligencia emocional [Relationships between coping with daily stress, self-concept, social skills and emotional intelligence]. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, E.; Esnaola, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Camino, I. Personal self-concept and satisfaction with life in adolescence, youth and adulthood. Psicothema 2015, 27, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrín, O.; Gómez-Fraguela, J.A.; Maneiro, L.; Sobral, J. Effects of parenting practices through deviant peers on nonviolent and violent antisocial behaviours in middle- and late-adolescence. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Legal Context 2017, 9, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Madariaga, J.M.; Arrivillaga, A.; Galende, N. Steps in the construction and verification of an explanatory model of psychosocial adjustment. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 9, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, D.M.; Lewis, M.A. Examining a social reaction model in the prediction of adolescent alcohol use. Addict. Behav. 2016, 60, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, M.; Gibbons, F.X.; Houlihan, A.E.; Stock, M.L.; Pomery, E.A. A Dual-Process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero, M.M.; Barragán, A.B.; Martos, A.; Sánchez-Marchán, C. Drug use in adolescents in relation to social support and reactive and proactive aggressive behavior. Psicothema 2016, 28, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David-Ferdon, C.; Simon, T.R. Preventing Youth Violence: Opportunities for Action; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Green, K.M.; Doherty, E.E.; Zebrak, K.A.; Ensminger, M.E. Association Between Adolescent Drinking and Adult Violence: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study of Urban African Americans. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2011, 72, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Molina, M.M.; Reingle, J.M.; Jennings, W.G. Does alcohol use predict violent behaviors? The relationship between alcohol use and violence in a nationally representative longitudinal sample. Youth Violence Juv. Justice 2011, 9, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Acosta, C.A.; Londoño, C. Modelo predictor del consumo responsable de alcohol y el comportamiento típicamente no violento en adolescentes [Predictive model of responsible consumption of alcohol and Typically not violent behavior in adolescents]. Health Addict. 2013, 13, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. La División del Trabajo Social; Planeta-Agostini: Barcelona, España, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe, R. The Connection between Academic Failure and Adolescent Drinking in Secondary School. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 79, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenqvist, E. Two Functions of Peer Influence on Upper-secondary Education Application Behavior. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 91, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Buss, A.H.; Perry, M. The Aggression Questionnaire. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, J.M.; Peña, M.E.; Graña, J.L. Adaptación psicométrica de la versión española del Cuestionario de Agresión [Psychometric adaptation of the Spanish version of the Aggression Questionnaire]. Psicothema 2002, 14, 476–482. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, M.M.; Jiménez-Giménez, M.; García-de Cecilia, J.M.; Rubio-Valladolid, G. Validación y Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de impulsividad estado (EIE) [Validation and Psychometric Properties of the State Impulsivity Scale (EIE)]. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 2011, 39, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arce, R.; Fariña, F.; Vilariño, M. Daño psicológico en casos de víctimas de violencia de género: Un estudio comparativo de las evaluaciones forenses [Psychological injury in intimate partner violence cases: A contrastive analysis of forensic measures]. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud 2015, 6, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariña, F.; Redondo, L.; Seijo, D.; Novo, M.; Arce, R. A meta-analytic review of the MMPI validity scales and indexes to detect defensiveness in custody evaluations. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

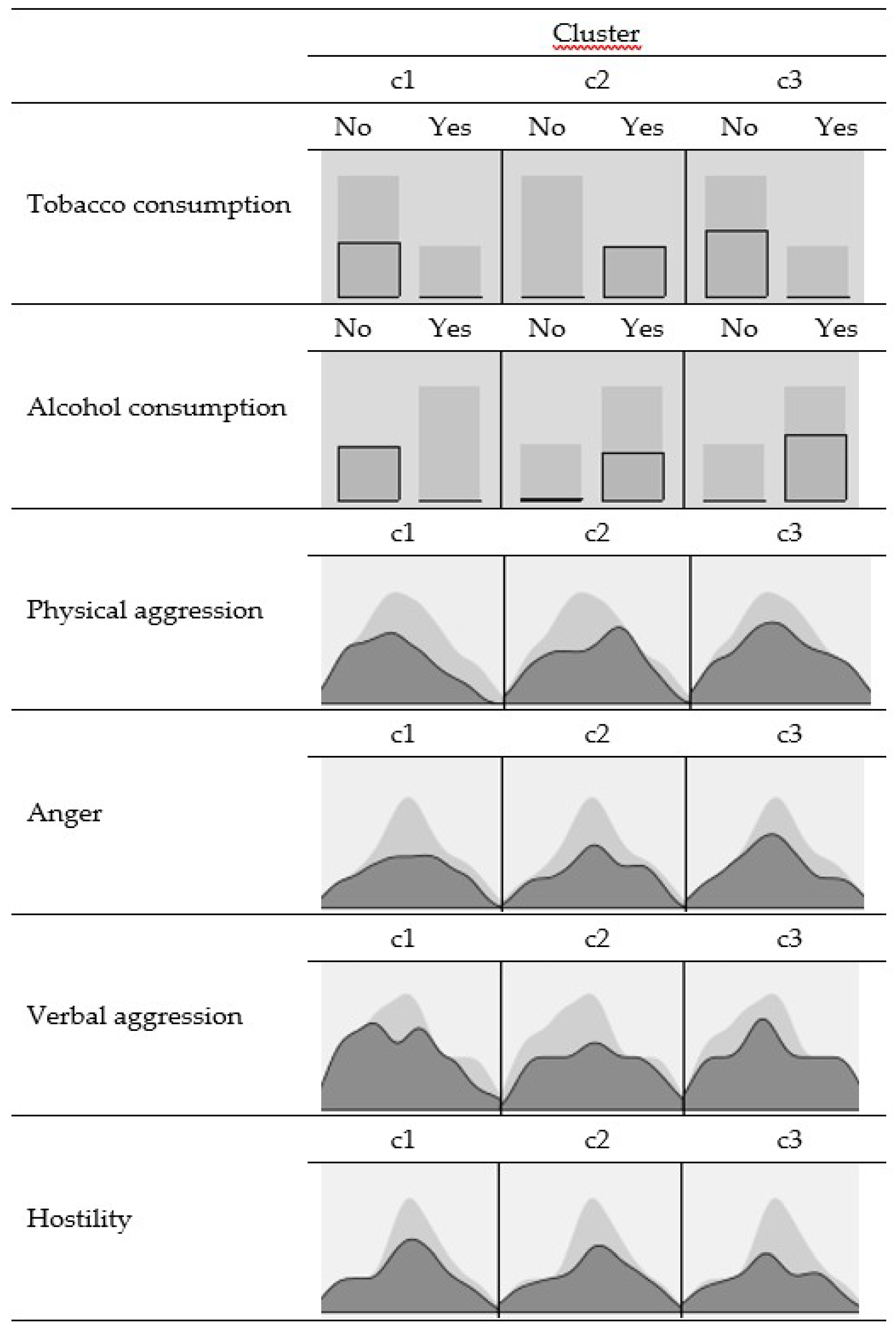

| Total Sample (N = 822) | Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Cluster 1) (n = 261) | 2 (Cluster 2) (n = 245) | 3 (Cluster 3) (n = 316) | ||

| Use of tobacco | Yes 29.8% No 70.2% | No 100% | Yes 100% | No 100% |

| Use of alcohol | Yes 66.8% No 33.2% | No 100% | Yes 95.1% | Yes 100% |

| Physical aggression | M = 2.47 | M = 2.19 | M = 2.79 | M = 2.45 |

| Verbal aggression | M = 2.68 | M = 2.46 | M = 2.83 | M = 2.74 |

| Anger | M = 2.91 | M = 2.63 | M = 3.16 | M = 2.94 |

| Hostility | M = 2.93 | M = 2.81 | M = 3.04 | M = 2.96 |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | η2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | DT | M | DT | M | DT | ||

| Gratification | 11.67 | 0.24 | 14.77 | 0.25 | 13.19 | 0.22 | 0.088 |

| Automatism | 10.82 | 0.23 | 12.79 | 0.24 | 11.99 | 0.21 | 0.039 |

| Attentional | 12.90 | 0.26 | 15.34 | 0.27 | 14.21 | 0.23 | 0.049 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Fuentes, M.d.C.; Molero Jurado, M.d.M.; Barragán Martín, A.B.; Gázquez Linares, a.J.J. Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents. Sustainability 2019, 11, 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030651

Pérez-Fuentes MdC, Molero Jurado MdM, Barragán Martín AB, Gázquez Linares aJJ. Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030651

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Fuentes, María del Carmen, María del Mar Molero Jurado, Ana Belén Barragán Martín, and and José Jesús Gázquez Linares. 2019. "Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030651

APA StylePérez-Fuentes, M. d. C., Molero Jurado, M. d. M., Barragán Martín, A. B., & Gázquez Linares, a. J. J. (2019). Profiles of Violence and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Relation to Impulsivity: Sustainable Consumption in Adolescents. Sustainability, 11(3), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030651