1. Introduction

“Sustainable tourism development requires the informed participation of all relevant stakeholders, as well as strong political leadership to ensure wide participation and consensus building” [

1]. This definition strongly points out that participation of various stakeholders and the promotion of such participation are a key element in Sustainable Tourism Development. Consequently, stakeholders play an important role in tourism development. It is important to remind that stakeholders can take both an active and a passive role, wherefore tourism development not only affects stakeholders but may also be affected by them [

2,

3].

The topic of stakeholders’ participation in tourism development has evidentially been a topic of research for many years. Particularly, host communities have received much attention in this regard. Already many years ago, it has been pointed out that community participation is often spoken of, using varying combinations of terms and definitions for the entity community [

4]. Hereby, it is important to remind that the nature of communities of a destination is extremely diverse and heterogenous [

5]. Over the years, many authors dealt with community participation in tourism in different ways [

2,

4,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, three main aspects appear when looking at these studies. Firstly, there seems to be a lack of studies that concentrate on very specific groups instead of researching the entire heterogenous community. Furthermore, studies still often rather point out the need and the reasons for community participation than looking at the nature of participation, which means that they rather “emphasiz[e] its necessity for a better tourism development with normative statements and catch-words” [

4]. Such reasons may be achieving a harmonious atmosphere within a destination [

18], ensuring a positive attitude towards tourism development [

9,

19], or ensuring a high degree of touristic authenticity within the destination [

19]. Finally, there seems to be a strong focus on researching participation in the context of developing countries and developing destinations. If so, barriers and drivers of participation in tourism development are thus rather explored through a focus on development and sustainable development in developing countries (see for example [

5,

7,

8,

9,

10,

13,

15]). Barriers to participation in developing countries are, for example people’s educational level [

9] or the legal system [

7,

20]. In this regard, different authors have come up with a detailed overview of the different success factors and drivers in community-based tourism approaches [

20,

21]. Although these factors are often related to tourism development in developing countries, factors such as residents’ skill and expertise [

20] or capacity building [

21] clearly also have important implications for tourism development in developed countries. Yet, there have also been some contributions in literature that explicitly focus on general barriers and drivers to community participation in developed countries. Such factors, for example, include residents’ place image [

22] or the general psychological empowerment of residents [

23].

Clearly, the idea of researching different groups of the community is not completely new. Looking at residents and tourism business people, is has been stated that those people tend to proactively support tourism development who benefit from tourism, mainly in economic terms [

6]. In this regard, it has been pointed out that up to now tourism research has mainly focused on Social Exchange Theory when dealing with the question why residents and other stakeholders participate in tourism development and what their attitude towards tourism is like [

24]. Yet, one specific group of the community is still under-represented in the literature. This group includes those people that are not employed in the tourism industry or are not related to the tourism sector in first and second instance and generally do not benefit from the tourism sector in economic ways as other members of the community do (e.g., employees of hotels or tour guides). Shortly speaking, non-tourism related residents are neither directly nor indirectly related to tourism [

18]. However, as outlined earlier, community participation concerns all members of the society. Not only popular urban but also rural tourist destinations are increasingly facing developments such as overcrowding and over-tourism [

25]. Since such destinations also represent living spaces [

25,

26], the need to consider the situation and incorporate the views of all residents becomes more evident than ever before.

The present study therefore aims to fill in a research gap by transcending the traditional approaches to community participation in tourism development and approaching the field more specifically. This study will investigate how a specific sub-group of the community, namely non-tourism related residents face the process of local participation in tourism development and what the main barriers and drivers are. Within the context of this study, local participation in tourism development is defined as non-tourism related residents’ participation in decision-making, developing concepts and products. The case-study researches non-tourism related residents of the Alpine Destination Bad Reichenhall in Bavaria, Germany. For this study, an exploratory qualitative approach is applied by conducting 15 problem-centered guideline interviews. The material derived throughout the interviews will then be analyzed in a qualitative content analysis. By exploring the participants’ perspective on participation in tourism development, it is aimed to finally come up with a typology of different types of non-tourism related residents. In addition, it will be explored what barriers and drivers act upon them in this regard. On the one hand, these insights will allow a better understanding of how these drivers can be further exploited. On the other hand, the main barriers to participation will be carved out in order to better overcome such barriers in the future. Based on these insights, it is aimed to pave the path for a more complex and differentiated way of encouraging different types of non-tourism related residents to participate in local tourism development.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

It has been indicated that the general topic of community participation has been dealt with in different ways in the past. Authors have placed a varying focus on the different domains of community participation. Consequently, studies range from approaches of regarding community participation as a general network approach in the field of local tourism governance [

27] to applying community participation in relation to very specific forms of tourism such as Ecotourism [

28] or even dive tourism [

29]. In line with the study of Tosun [

30], this study picks up on the approach of differentiating between different groups’ perceptions on community participation. Yet, in this study, it is aimed to give attention to the under-researched group of non-tourism related residents within the community of the case destination Bad Reichenhall. Furthermore, this study goes in line with approaches taking a closer look to the extent of community participation by differentiating between different stages of participation [see for example [

7,

11,

15,

26,

30,

31]. Such stages of participation will be presented in order to derive a decent model for the case of non-tourism related residents.

For the interest of this study, it is important to explore the field through the perspective of the potential participants, non-tourism related residents. In this regard, the theory of Participatory Design (PD) offers adapted perspectives on non-tourism related residents’ participation or stakeholders’ participation in general and will be presented in the following. PD emerged in the Scandinavian countries and was strongly linked to information technology and democratic movements in the field of work life [

32,

33]. It will be shown how PD increasingly enters new domains, among which tourism development represents a suitable field of research. Furthermore, it will be taken a closer look to the nature of participation and what forms participation can take in the field of stakeholder participation, finally resulting in a typology of participation. For this, it is aimed to narrow down participation not only in a tourism-centered context but also in a broader context, taking a closer look to general research on citizen participation see [

32,

34]. The holistic view on the topic of stakeholder participation will reveal important premises for the empirical research on participation of non-tourism related residents in tourism development.

The clear definition of the entity residents is also reflected in the definition of the term participation. Thinking within the context of tourism, there must be a first basic distinction of what forms participation can take. Looking at destinations more in detail, it appears that their product consists of services such as accommodation, gastronomy, transport, events, and even the landscape and the local population can be part of it [

35]. Transferring this to the field of participation, it becomes clear that it is generally not only about carrying out such services but also about planning and developing the just described destination product. Therefore, on the one hand participation can be seen in economic terms such as in the case of local people acting as hosts, guides or employees in the tourism sector. On the other hand, however participation may be seen in the context of participating in decision making processes or participating in the whole process of developing a local tourism concept or product [

26]. Within the context of this study, local participation in tourism development is therefore defined as non-tourism related residents’ participation in decision-making, developing concepts and products. It is thereby avoided to simply speak of community participation since the broad term community participation refers to an even more heterogenous group of stakeholders.

2.1. Participatory Design

From a general point of view, “Participatory design is an attitude about a force for change in the creation and management of environments for people” [

36]. This perception of PD successfully summarizes the different parts coming together in this concept. The underlying nature is characterized by change. It is about making a change and acting towards a better future. The object is constituted by a certain environment that is created, re-created and managed day by day. As well, the subject is represented by the people (citizens), who become able to manage their environment for their own purposes. It is about putting citizens in an active instead of a passive role, which eventually results in a better shaped environment for them [

37]. PD makes use of approaches and methodologies that see non-designers, namely users or other stakeholders, as active parts in the designing process [

38,

39]. This relates to the key question, already outlined in the introduction, whether stakeholders are attributed a rather passive or active role. As PD is gaining increasing attention in many fields, it is important to track down the core idea behind this approach. The roots lie in “various social, political and civil rights movements [in] the 1960s and 1970s” [

33]. PD has emerged from the basic belief that people, who are affected by a certain design, should be able to be part in the process of generating such design. There are two guiding principles behind PD. On the one hand, participation is driven by a basic democratic attitude. On the other hand, it is acknowledged that participants dispose of tacit knowledge that may represent a valuable component of the design process [

40]. Yet, another principle behind PD has been pointed out, that is learning from each other through mutual understanding throughout PD [

41]. Overall, it appears that democracy, learning and tacit knowledge of participants are the main drivers and principles behind PD.

Over the years there has been a significant shift in the domains of PD, resulting in more community-oriented research [

39]. It has been stated that this change correlates with the question which object is designed through PD [

42]. There seems to be a shift from PD happening within an organizational setting towards a public setting. Broken down, this means that PD has moved to public issues, in which people from the society are equipped with the right to have a say. Community-based participatory design can thus be seen as an upcoming recent domain of PD [

43]. In this regard, the focus is also put on the participative inclusion of local views in the design process by searching for tools, techniques and processes that appear to be solution-oriented for the respective situation (problem) of the community [

44]. Another aspect of PD in the field of communities is to clarify the underlying goal or reason for letting members participate in the design process. The instrumental and the transformative approach represent two distinct approaches in this regard [

44,

45]. The former sees participation of the local community as a way to increase their acceptance and support for a specific matter, and thus level up the outcome of a project [

45]. The latter is based on reasons of equity and empowerment, using participation for providing disadvantaged people with the right means to shape their lives on own terms and thus promote social equity [

45]. The instrumental approach is seen to be stronger related to the traditional character of PD. In contrast, the transformative approach goes more in line with new perceptions, opening up the space and scope of PD [

44]. Thereby, PD literature not only explores reasons for participation but also acknowledges that participation takes different forms and is performed to a varying extent.

2.2. Models of Participation

In the context of this study, local participation in tourism development is defined as the participation of non-tourism related residents in decision-making and developing tourism concepts and products. However, there must be an even closer definition of participation. In a rather general context of communities, the following definition of participation has been set up: “The means by which people who are not elected or appointed officials of agencies and of government influence decisions about programs and policies which affect their lives” [

34]

. This brings a new aspect to the definition of participation for the context of this study. By speaking of influencing decision-making, it becomes clear that participation does not necessarily mean to carry out decision-making. It can also refer to very basic forms of participation, such as staying informed about developments or simply signalizing decision-makers that one is aware of such processes and cares about the decisions. A very prominent work in this regard comes from the author Arnstein [

46]

, who dealt with the topic of participation during a time when it was often spoken about the

have-nots. These are the citizens of a society who generally do not dispose of the power and opportunities to influence governmental decisions and programs.

“Citizen Participation is Citizen Power”, defined more in detail as following: “It is the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future. It is the strategy by which the have-nots join in determining how information is shared [and] goals and policies are set […]” [

46]

. In the light of these circumstances, the

Ladder of Participation (LOP) has been developed, which represents an overview that aims to structure participation more precisely. The resulting model is structured in eight different levels ranging from

Non-participation to higher levels of participation, in which citizens execute control over decisions and planning processes [

46]. Scanning the literature for more ways of structuring participation, a common structure appears, even though the authors originate from several scientific fields, and therefore place their focus on different parts.

Table 1 provides an overview of all approaches. These approaches mainly result from works in the field of community studies and citizen participation in public matters, with two of them in the field of tourism research [

4,

13]

.The lower part of the overview shows that all approaches try to systematize the process of participation by splitting it up into different stages. The authors come up with a deviating number of participative stages. The higher the number of stages, the more detailed the process of participation is grasped by the author. The LOP, depicted on the left side of table, contains the highest number with eight stages [

46]. In the approaches on the right side of the table, the process is split up in only two distinct general categories [

36,

44]. The authors’ approaches match in a thematic way. Only the structural depth of the approaches varies from author to author. Furthermore, it becomes clear that the LOP, as the oldest work, serves as an underlying framework. It serves as the construct for most of the other approach since all authors refer to the basic segmentation set up by Arnstein

. 2.3. Derived Model of Participation for Non-Tourism Related Residents

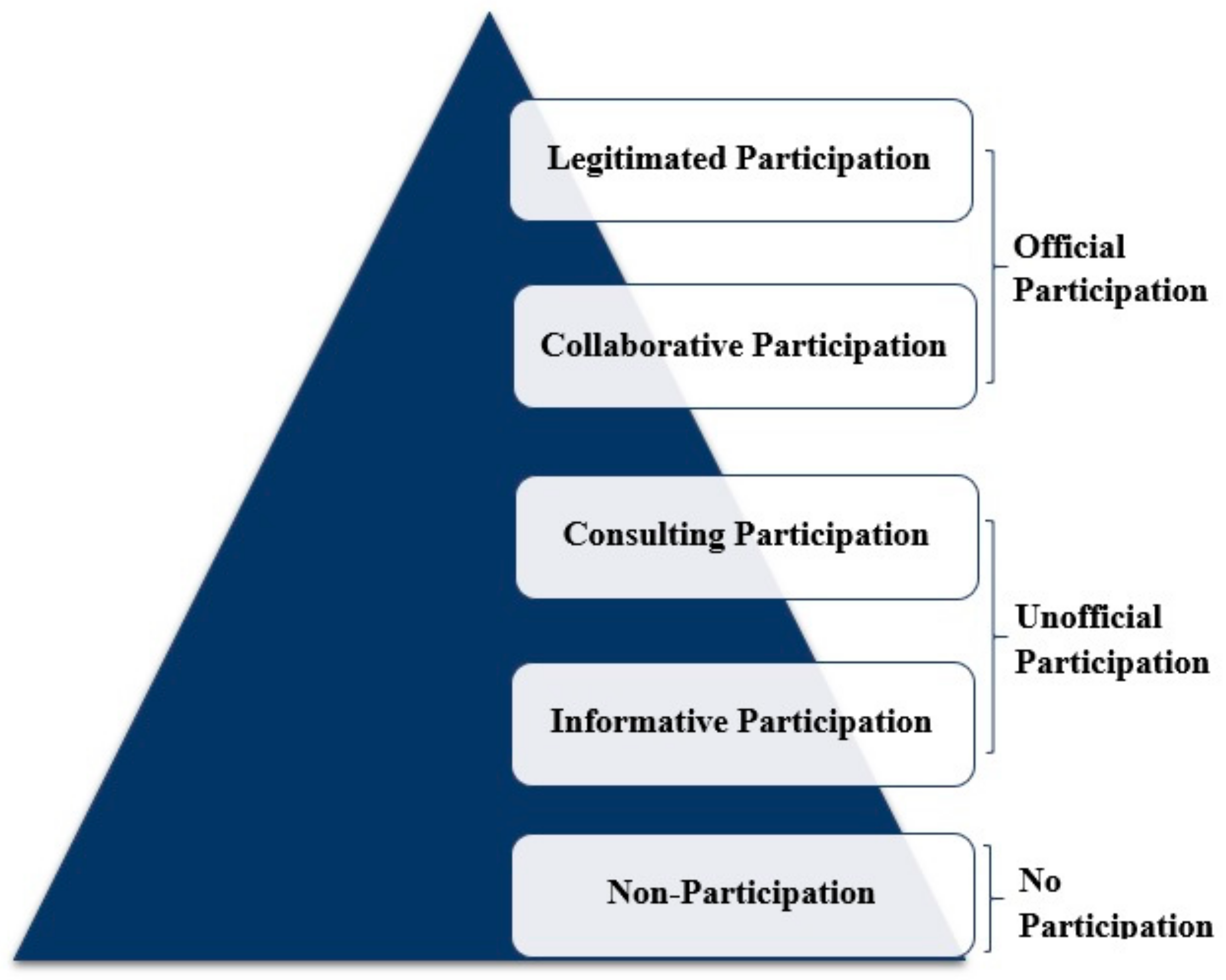

Based on the different approaches of arranging the stages of participation, it is now aimed to develop an adapted model of local participation in tourism development for the present study, which represents a mixture of the approaches presented above. Thereby, it is not aimed to dispute the meaningfulness of the existing approaches. It is rather tried to combine the approaches in order to come up with a specific model for the case of non-tourism related residents. Furthermore, it is explicitly avoided to uses negatively connoted expressions such as Instrumental or Pseudo-participation as in the case of non-tourism related residents some interviewees may not perceive lower stages of participation as inherently negative. For the resulting pyramid of participation (see

Figure 1), a general three-part solution was chosen. Thereby, one important assumption from earlier approaches was adopted: Participation may be carried out as

Official Participation on high levels or

Unofficial Participation on the lower levels. Moreover, the general category of

No Participation was added, which in some approaches is left out. However, in the context of this study, some non-tourism related residents may be placed within this category. In order to not preclude this case, the stage must form a part of the underlying structure being applied in this study. This fact represents another reason for the necessity to develop a specific model for the study in the context of non-tourism related residents.

For this study, it was decided to further break down this three-part structure. On the one hand, this gives greater insights on how these different forms of participation are shaped. On the other hand, a more fragmented structure allows to meet the potential heterogeneity of non-tourism related residents’ participation in tourism development. It needs to be pointed out that the regularity behind each stage of participation does not necessarily imply a certain degree. A participant may go to a public tourism-related event on a very regular basis but still choses not be part of a project, workshop, action group or a political party, remaining on the level of Consulting Participation. Furthermore, it is not predefined that going up the stages of participation means passing each stage. An interested participant may directly choose to go from the informative stage to the collaborative level. However, the pyramid generally displays the stages, which may be passed on the way to Official Participation. The shape of the pyramid reflects the aspect that for now it is assumed that the majority of non-tourism related residents is located on lower levels of participation in tourism development with fewer people choosing to participate in an official way.

The model starts with

Non-Participation, including those non-tourism related resident who show no involvement or are not informed about local tourism development. The next stage is called

Unofficial Participation since there is still no real obligation behind this form of participation. It contains the subordinated stages of

Informative Participation and

Consulting Participation.

Informative Participation sets in when the transition between

Non-Participation and participation takes place. The participant may receive information rather passively but may also actively seek information through different channels. With an increasing active behavior, such as sharing an opinion or providing assistance in tourism matters, the stage of

Consulting Participation is reached (e.g., attending a public town hall meeting). With rising extent of such participation,

Official Participation, is reached, which means that the participant has chosen a certain degree of obligation or is committed to a project or topic. Within the next stage,

Collaborative Participation, non-tourism related residents may be involved in different workshops or participative projects without any attribution of decision-making power. Reaching the upper stage of

Legitimated Participation, at least some degree of decision-making power is attributed to the participant. In contrast to other authors’ approaches (see

Table 1), this stage may not be characterized by extreme forms like citizen control since it is not the general task of non-tourism related residents to fully control or decided about tourism development.

Overall, the theoretical pillars aimed to establish a sense for the under-researched nature of participation in tourism development from the perspective of non-tourism related residents of developed destinations. It was also aimed to show the need of breaking participation further down and looking at different forms and extents of participation. Thereby, it is now tried to transcend traditional studies by focusing on the barriers, drivers and nature of participation. Traditional studies tend to generalize participation, only pointing out the necessity of participation and often apply a focus on developing destinations as the object of research. Finally, the theoretical contributions made clear that there is a need to consider the participants’ perspective when researching local participation in tourism development. In the light of the interest of this study and the literature review, the following research question was derived: How do non-tourism related residents face the process of participation in tourism development? What are the main barriers and drivers?

3. Materials and Methods

The study applies a qualitative approach to deal with the research question. Although participation in tourism development has been of great interest over the past decades, it has been shown that most studies focus on communities in general, the reasons for participation in tourism development and often research cases in developing countries. Therefore, this study explicitly draws back on the exploratory character of qualitative research [

51]. More specifically, problem-centered guideline interviews were conducted within this qualitative approach. The relatively open character of this form of interviews and the focus on the interviewees’ perspectives on the object of research allows a maximum gain of knowledge [

52], which is vital for this study. By this explorative approach it is not aimed to generalize the results that may not be fully representative but instead provide first insights on the topic of research.

In preparation of the problem-centered guideline interviews, the following sampling strategy was chosen. It is acknowledged that selective sampling and theoretical sampling display distinct characteristics. However, the two strategies also provide connecting factors. It is argued that theoretical sampling may follow a first selective sampling approach, which means that further participants are selected based on the material gained through the first phase of research [

52,

53]. In contrast, this discussion is picked up in another article, that discusses the difference or similarity between purposeful and theoretical sampling strategies [

54] and states that actual theoretical sampling does not provide any sampling frame before the research [

54,

55]. Despite ongoing discussions how and to what extent theoretical sampling and selective sampling can be used in combination, this study adopts the idea of combining the two strategies.

It was required that all interviewees reside in the city of Bad Reichenhall. Furthermore, one major characteristic of the interviewees must be mentioned, which is the fact that the interviewees are not related to the tourism sector as outlined in the theoretical part. The participants of this study are very heterogeneous in terms of their professional background and voluntary activities. In preparation of the interviews, a call for voluntary participants was made through local contact persons in the destination. These contact persons were asked to spread the request for participating in interviews with non-tourism related residents of Bad Reichenhall. 14 persons contacted the researchers. Among these volunteering people, a selection based on further criteria was carried out, which resulted in the conduction of ten interviews. It was thereby tried to ensure a well-balanced mixture between men and women and a relatively balanced range in terms of their age. Following these first ten interviews, it appeared which kind of additional interviewees would still generate new insights and thus could further contribute to new knowledge. As a result, the next interviewees were chosen by a theoretical sampling approach. This was mainly done with reference to the theoretically developed pyramid of participation. Since the participants are placed on different levels of this pyramid throughout the interview, it could be detected what levels are not or only barely covered by the first ten participants. It has turned out that particularly the higher stages of participation have not been covered yet. Therefore, in the second call it was explicitly asked for non-tourism related residents who have experience in participating in tourism development to explore their view on non-tourism related residents’ participation. Finally, another five interviews were conducted. After the second round of interviews, the levels above Non-participation in the pyramid of participation were covered by at least one interviewee. The final 15 interviewees chosen for this study are made up of seven women and eight men. The interviewees’ ages approximately range from 25 to 65 years.

For the interview guideline (see

Appendix A), thematic blocks were formed, which refer to the theoretical foundations of the present interest of research [

56]. The blocks range from general contents to very specific contents. Therefore, each block incorporates different perspectives from the theory, not only referring to one specific theoretical part. The first block explores the personal characteristics of the interviewee and the rootedness in the destination. In the second block, the focus is on exploring the current status quo of the interviewee’s level of participation in tourism development. The third thematic part directs the view on the residents’ level of future or desired participation and represents a creative form of exploring the respective barriers and drivers.

For the analysis of the interview-material it was decided to apply a qualitative content analysis. More precise, a typological analysis suits best for the present case as the research question asks for the way how non-tourism related residents face the process of participation in tourism development. In this regard, it has been pointed out that a typological analysis builds on a prior carried out content-structural or an evaluative analysis as it is required to draw on existing attributes in a typological analysis [

57]. For this study, a first content-structural analysis is carried out since this form of analysis suits for problem-centered guideline interviews [

57]. In this regard, it is also important to remind that the second part of the research question asks for barriers and drivers to participation, wherefore a content-structural analysis is also necessary, which resulted in the following system of main codes.

Personal life

Information situation in the field of local tourism

Information channels

Tourism as a public domain

Current and past level of participation

Drivers to participation

Barriers to participation

Aspiration for higher stages of participation

Appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation

Concrete proposals for means of participation

In another step of the content-structural analysis, the main codes shown above were further divided in sub-codes and sub-sub-codes to prepare the typological analysis. For constructing the typology, the polythetic typology was applied. Since the typology is inductively constructed on the basis of the material, it can be spoken of a polythetic natural typology that is set up through a systematic way of analyzing and assembling the material [

57]. The resulting attribute space of the typology is made up of the following three main codes and the respective sub-codes.

With the attribute Current and past level of participation, the typology gives insights what experience the person has in the field of participation in tourism development. The attribute Aspiration for higher stages of participation directs the focus into the future and explores the motivation for future participation in tourism development. With the third attribute, Appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation, it is aimed to depict the sense that a non-tourism related resident sees in participation in tourism development. All three attributes provide important implications in terms of the underlying interest of this study.

4. Case Study Destination

For the case study, the Bavarian city of Bad Reichenhall, which counts around 18,000 inhabitants, is chosen as the field of research [

58]. Bad Reichenhall is situated in the area of application of the Alpine Convention and thus qualifies for the aim of sustainable tourism development in the Alps [

59]. Bad Reichenhall is an Alpine Destination, which in 2001 was awarded the title

Alpine Town of the Year [

60]. This title is attributed to towns that show efforts to successfully implement the contents of the Alpine Convention, such as sustainable development and the protection of the alpine landscape [

61]. Furthermore, since 2006 the destination has been a member of the international tourism network Alpine Pearls, promoting sustainable tourism solutions such as soft mobility [

62]. In the end of 2017, a new destination management and marketing strategy was set up for Bad Reichenhall. This was the result of a 5-year long process of company analysis, branding and organizational restructuring [

63]. In 2018 the destination of Bad Reichenhall—Bayerisch Gmain recorded nearly one million overnight stays (987,593) and 203,013 guests. In comparison to the year 2015, this was an increase by respectively 7.5% and 24.2% over 3 years [

64]. Thus, tourism plays an important role in the case destination.

Bad Reichenhall is home to some of the most frequently visited tourist attractions in the whole county of Berchtesgadener Land. These include the spa Rupertus Therme, Café Reber, the mountain area Predigtstuhl and the salt works [

65]. In terms of accommodations, the destination offers a variety of possible options. The latest available statistics from 2011 reveal that most guests choose classical hotels and guesthouses as their preferred type of accommodation [

66]. Hotels with health cure offers, clinics, bed & breakfast houses, holiday apartments and privately-owned guesthouses play a minor but nearly equal role in this regard. One aspect that stands out very clear is that the average length of stay differs greatly among the various types of accommodation. Whereas the overall average length of stay is approximately 5 days [

64], the average length of stay in clinics is much higher (e.g., 22 days in 2011) since these stays include aspects of long-term health treatments. Clinics therefore are on the top when it comes to overnight stays statistics [

66].

5. Results

In the following part, the results of the study will be presented. It will be shown in what ways tourism represents a public domain for the participants of the study and what barriers and drivers act upon them when it comes it local participation in tourism development. Finally, it will be shown what types of non-tourism related residents could be detected through the case study approach.

5.1. Tourism as a Public Domain

The question in what ways tourism represents a public domain has specifically taken a key position in the light of Participatory Design. Finding answers to this question serves as another clear indicator for exploring the residents’ connection to local tourism. The participants named five different areas in which tourism manifest its public nature. In order to interpret the themes more in detail, the following list shows how many interviewees named each area in terms of the public nature of tourism.

Economic importance of tourism (11 interviewees)

Positive impacts of tourism on personal life (9)

Daily-life encounters with tourism (8)

Job-related contact with tourism (8)

Negative impacts of tourism on personal life (6)

Other (6)

The mostly named economic importance of tourism indicates that non-tourism related residents do recognize that tourism significantly contributes to all residents’ living conditions in the destination of Bad Reichenhall. One interviewee even thinks that this dependence creates a unity between tourism and the local population: “Tourism is part of the public in Bad Reichenhall. It is inseparable, it is a unity. We are part of tourism and we live with tourism. And partly people also live from tourism. That is why it is inseparably linked” (Interview 5, translated). This underlines that in the present case non-tourism related residents do not regard tourism as an ordinary economic sector as they stress the economic scope of tourism for the whole region. Another area, in which non-tourism related residents see how tourism manifests as a public domain, are positive and negative impacts. In terms of positive impacts, an interviewee states: “For me, one effect is that we have the philharmonic orchestra, the health and cure garden, the cable car Predigtstuhlbahn. Just a lot of things […] that are just there and would not be otherwise. So, if tourism would not exist, certain infrastructure would not be there” (Interview 7, translated). However, as indicated above, not only positive impacts of tourism were mentioned by the participants. On the one hand, the participants speak of traffic problems in the city (Interviews 2, 6, 9, 15). On the other hand, the interviewees state that costs of living and housing prices tend to rise as more and more people visit the destination but also choose the destination as their new place of living (Interviews 1, 4, 6). The naming of daily-life encounters with tourism makes clear that not only tourism-related residents like employees of hotels or spas encounter tourists have these encounters but also non-tourism related residents.

Rather surprisingly, over half of the non-tourism related residents interviewed in this study see tourism as a public domain due to a job-related contact with tourism (Interviews 1, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14). However, the basic assumption of this study, which says that non-tourism related residents are not employed in the tourism sector, is still valid as the job-related contact with tourism does not take place through a job within the tourism industry. Two interviewees work in health care, which is not a tourism-specific sector but a sector also tourists need when being on holiday. Another interviewee reports that her family runs a pharmacy in the city of Bad Reichenhall, which clearly benefit from induced effects from tourism, particularly in the peak season. Another interesting aspect was mentioned by an interviewee, who engages in religious and church-related work. She reports that much more people are attending church services in tourism peak times like summer, a factor that influences the planning and organization of a service.

Overall, it could be shown that there is a fundamental connection between non-tourism related residents and the tourism sector at later instance. Even if the target group is not directly or indirectly related to tourism it turns out that in a destination like Bad Reichenhall, tourism does not perform in a parallel world. Therefore, it can be summarized that according to the interviewees there are lots of areas in which tourism clearly represents a public domain in the destination of Bad Reichenhall.

5.2. Barriers and Drivers to Local Participation in Tourism Development

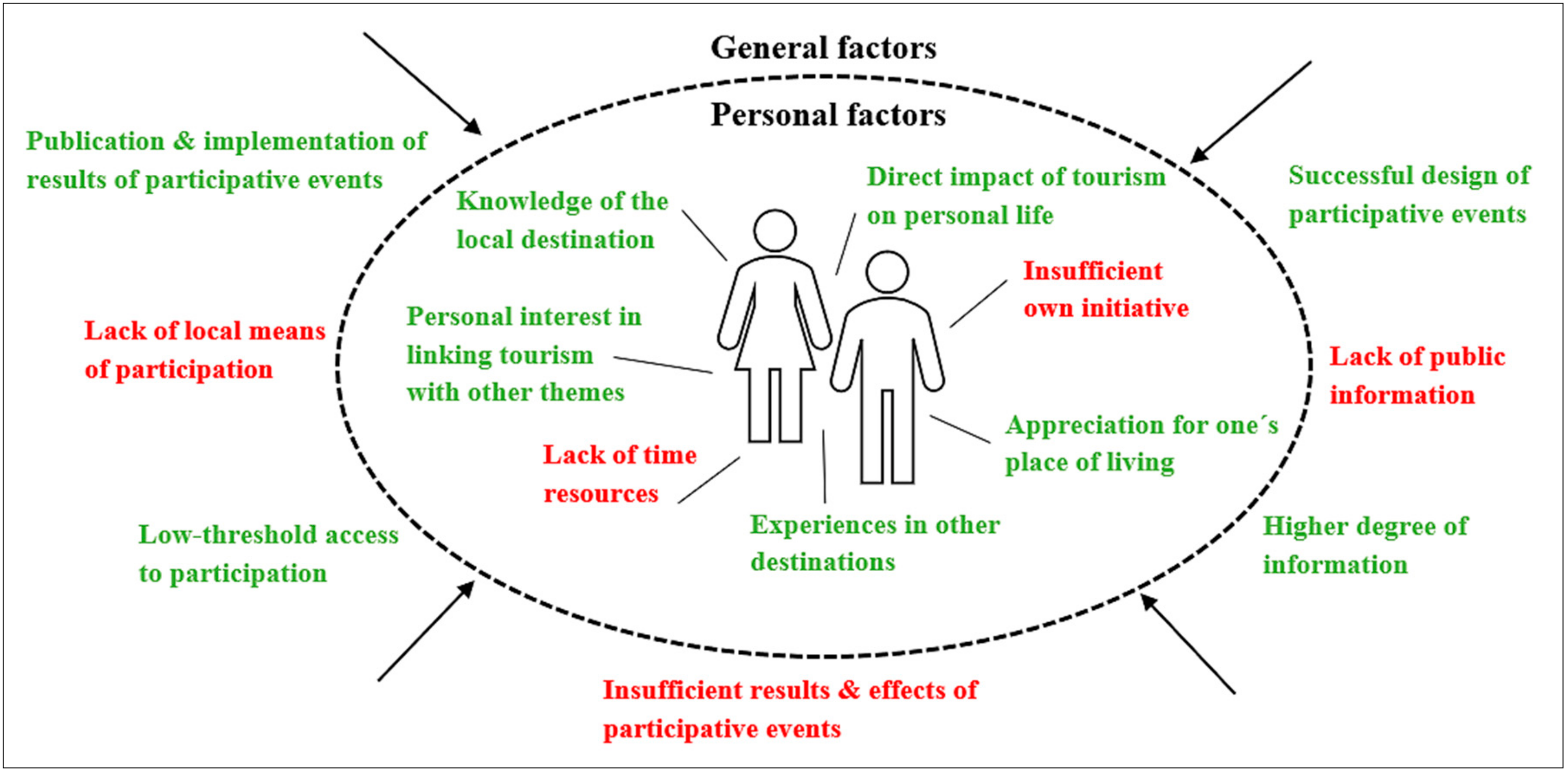

Figure 2 shows both the barriers and drivers named by the participants of this study. Barriers are marked red whereas drivers are marked green in the figure. The figure also includes the structure of splitting barriers and drivers into general factors, acting upon the residents from outside, and personal factors, impacting the residents from a personal side.

Especially, the detection of the barriers and drivers reveals that non-tourism related residents are impacted by a great number of factors. In this regard, not only personally bound barriers and drivers, but also general ones appeared. In terms of barriers, it turned out that the participative process may fail due to a personal lack of time resources or an insufficient own initiative: “I am not extremely interested because I think it is alright and other people care about this topic. I am not making my living from tourism, so I do not have to be that interested.” (Interview 7, translated). Other reasons are a lack of public information, participative events and an inappropriate way of dealing with the results and effects of participative events. Especially the latter one seems to strongly discourage the interviewees from participating in tourism development. One interviewee describes that he has witnessed such worries in practice when he attended a town hall meeting, stating that “it is rather superficial what is happening there” (Interview 3, translated). In contrast, the main personal drivers are knowledge of the local destination and experiences in other destinations, a direct impact of tourism on the personal life, an appreciation for one’s place of living and a personal interest in linking tourism with other themes. Linking participation in tourism development with other topics may represent a valuable option. Three interviewees claim that they are experts in sports events, so they could imagine participating in sports-related tourism development (Interviews 1, 7 and 13). General drivers named were a higher degree of information, a successful design of participative events and a decent way to deal with the results of participative events. A very prominent general driver named by the interviewees is “a low threshold access” (Interview 8 & 15, translated) to participation. One interviewee demands a step towards the residents in order to avoid a far too big inhibition threshold to participate (Interview 1).

5.3. Types of Non-Tourism Related Residents

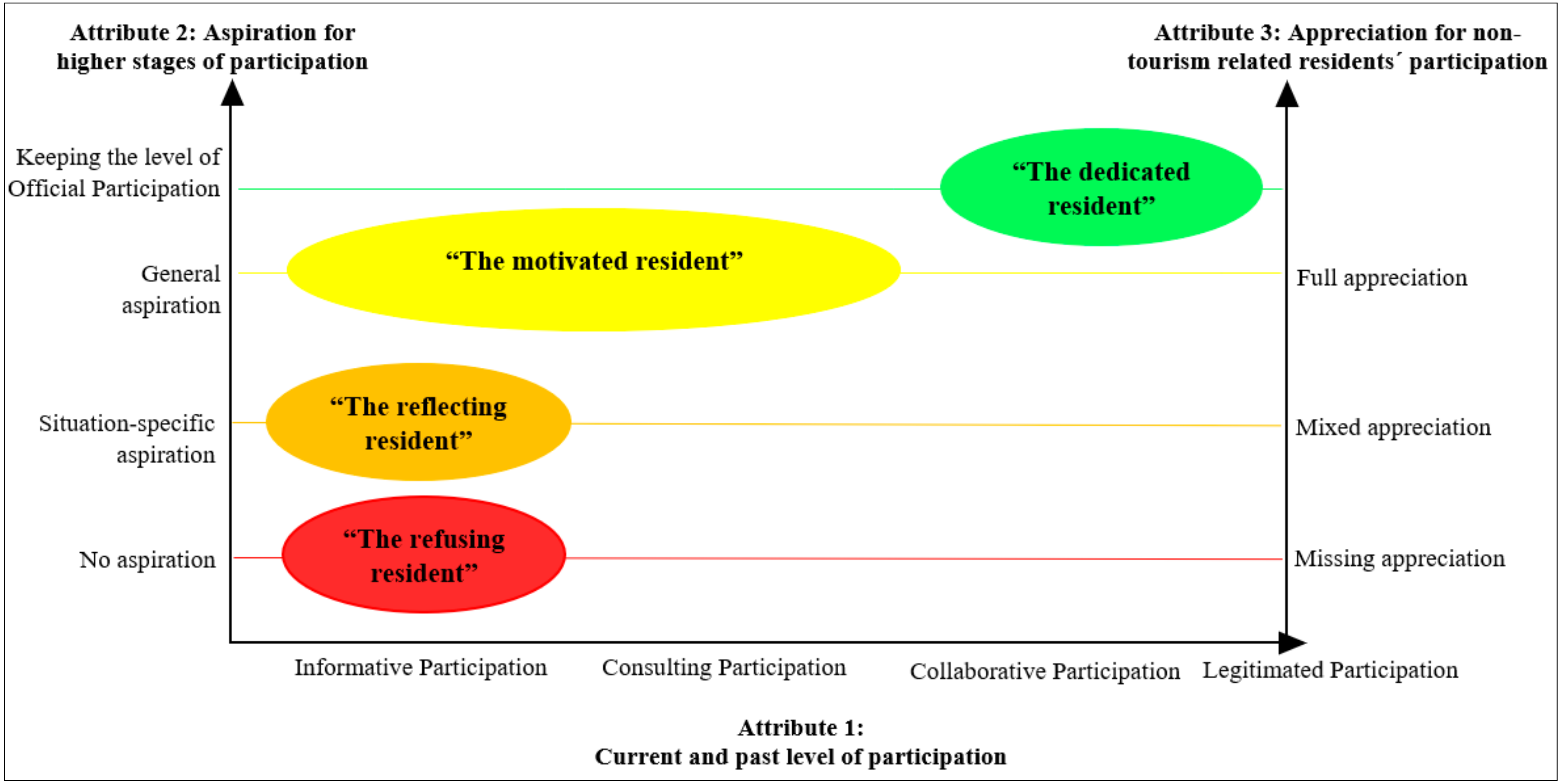

The results of the typological analysis can be found in the following overview (see

Figure 3), which summarizes the characterization of different types of non-tourism related residents within the attribute space of participation in local tourism development.

According to the attributes located on each axis of the diagram, it can be seen where the different types of non-tourism related residents are located within the attribute space. The axes show a rising extent of the respective attribute, marked by arrows. Interestingly, as pointed out earlier, no type could be detected that shows absolutely no current and past level of participation, which is therefore not included in the attribute space. Generally, the typology incorporates the underlying interest of the study. It is about pointing out the way how non-tourism related residents face the process of participation in tourism development. As outlined earlier, the typology focuses on past, present and future aspects. All three attributes of the typology therefore have a high significance for the way how a non-tourism related resident faces local participation in tourism development. The four different types of the constructed typology will now be presented more in detail.

Type 1—The refusing resident: “No, thanks!”

The refusing resident is basically informed about local tourism and tourism development but has not exceeded the level of Informative Participation yet. Asking for an aspiration to be part of tourism development on a higher level, the refusing resident says: “No, I am interested in [tourism] but I do not have any ambitions for that” (Interview 12, translated) or “I do not want to spend my time for that” (Interview 6, translated). Regarding the level of appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation, the refusing resident clearly shows a missing appreciation. He or she cannot imagine to positively contribute to tourism development on own terms or simply sees participation in tourism as a topic for those people that are related to the tourism sector: “I think if I were a host, I would be more interested. Then I would certainly go to events and would be more interested” (Interview 12, translated). Overall, the first type of the typology is named refusing resident since it is rather unlikely to convert this type of non-tourism related residents for a higher level of participation than the level of Informative Participation.

Type 2—The reflecting resident: “Maybe, but if …”

The reflecting resident is well informed about local tourism and tourism development. Although he or she may have attended a participative event in the past, this only occurred on a one-time level and not necessarily with a primarily tourism-specific focus. So, generally the reflecting resident is located on the lower stage of Unofficial Participation. Regarding the aspiration for higher stages of participation, the reflecting resident neither is fully motivated to level up participation nor completely excludes the possibility to do so. As long as the time resources are limited, the reflecting resident is busy with existing activities. Yet, in specific situations, this type of resident can imagine participating on a higher level. “If it is about topics which I am personally extremely interested in, I would [level up participation] since it is important to me. But right now, it is enough for me to receive information on what is happening at the moment” (Interview 4, translated). Furthermore, the reflecting resident shows a mixed degree of appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation in tourism development. Although he or she has some doubts about the sense of participating in tourism development, some specific areas are named in which the reflecting residents can imagine contributing to tourism development: “It’s difficult. If at all, you could only contribute your own experiences, for example from the own spare time activities” (Interview 14, translated). Overall, the just described type of resident is named reflecting resident since the successful encouragement of such resident for participation depends on several factors but is certainly not pointless.

Type 3—The motivated resident: “Yes, of course!”

The motivated resident ranges on the stage of Unofficial Participation, reaching from Informative to Consulting Participation. This type is very well informed and particularly interested in matters of tourism. There is a general aspiration for reaching higher stages of participation in the future. The specifically desired level depends on the current level. The motivated resident currently positioned on the level of Informative Participation, says: “Right now, I feel like I am on the level of information […]. But I would certainly like to voice my opinion and share my ideas if I had the opportunity to do so” (Interview 1, translated). The motivated resident already located on the level of Consulting Participation, states: “I could imagine targeting one step higher, the cooperation, to deal with a specific project more in detail. There are local initiatives, so for example joining such citizens’ groups not only with a signature but actively” (Interview 3, translated). So, the motivated resident shows a distinct desire to contribute and actively share opinions and ideas. Finally, the motivated resident has no doubts about the sense of involving non-tourism related residents in local tourism development and expresses full appreciation for such processes: “I believe that there is an important connection that the resident knows that he or she is involved and taken into account in such projects” (Interview 11, translated). This type of non-tourism related residents was named motivated resident since the intrinsic motivation is already existing. Thus, the motivated resident represents a promising target group.

Type 4—The dedicated resident: “Yes, we all can!”

The dedicated resident has already reached the levels of Official Participation in tourism development. This does not imply that the dedicated resident has run through all stages of participation before. In the present study, the dedicated resident has rather achieved this level of participation through the local political engagement and is thus confronted with matters of tourism on the level of Official Participation. As the dedicated resident has already achieved the highest levels of participation, it is difficult to narrow down the aspiration for higher stages of participation. However, in the context of this study the dedicated resident shows no signs of leaving the stage and quitting the current participative work. It is characteristic for this type to show a full appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation, pointing out the ability of all residents to make a contribution: “What [the resident] brings along is local knowledge […] and experiences. But I also believe that people who are not involved in the daily business [of tourism] simply bring along a different perspective on things. They see things unbiased and think of solutions that are not obvious to tourism-related people” (Interview 15, translated). So, this type of non-tourism related resident is named dedicated resident since he or she shows a great dedication to local fields of action such as tourism and strongly supports the idea of involving all residents, either tourism-related or not, in local tourism development. In this study, the dedicated resident’s participation in tourism development was strongly linked with local political work.

Especially in terms of the aspiration for higher stages of participation and the appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation, the four types significantly differ in the way how they face participation. It seems quite hard to encourage type 1, the refusing resident, for a higher stage of participation in the future as this type faces participation in a rather negative way. However, convincing non-tourism related residents for participation appears to be even more promising when looking at the reflecting and the motivated resident. Both of them may not have participated on higher levels yet. Whereas the reflecting resident evaluates the right situation and needs a specific trigger for going one step further on the pyramid of participation, the motivated resident faces participation fully positively and is thus one step ahead in this regard. It is more about giving motivated residents the right platform to act out their motivation to participate. In addition, the results regarding the fourth type, the dedicated resident, underline that even non-tourism related residents have the chance and ability to participate in tourism development on the levels of Official Participation. In this regard, the study revealed that political engagement represents a way how to successfully climb higher stages of participation, in which tourism plays a role besides other topics. Therefore, choosing political means to participate in tourism development represents an important path for non-tourism related residents. The typology shows that non-tourism related residents are neither inherently unable nor unwilling to participate in tourism development.

6. Discussion

The study investigated how non-tourism related residents face the process of participation in local tourism development and what the main barriers and drivers are in this regard. Although the research question is split up into two parts, there is a strong connection in between. The typology described above (see

Figure 3) gives clear insights on the way how different non-tourism related residents face the process of participation. These different ways must be considered from the background of the barriers and drivers. Only in combination, these insights allow for a better understanding of non-tourism related residents’ perspective on the level of participation in tourism development. However, it could not be detected that each type faces specific barriers and drivers. This is because the refusing type does not think too much about barriers and drivers since he or she is simply not interested in participating in tourism development. In contrast, the dedicated type extensively thinks about barriers and drivers to participation, yet from the perspective of others since this type has already overcome the barriers or has already been sufficiently driven to participate.

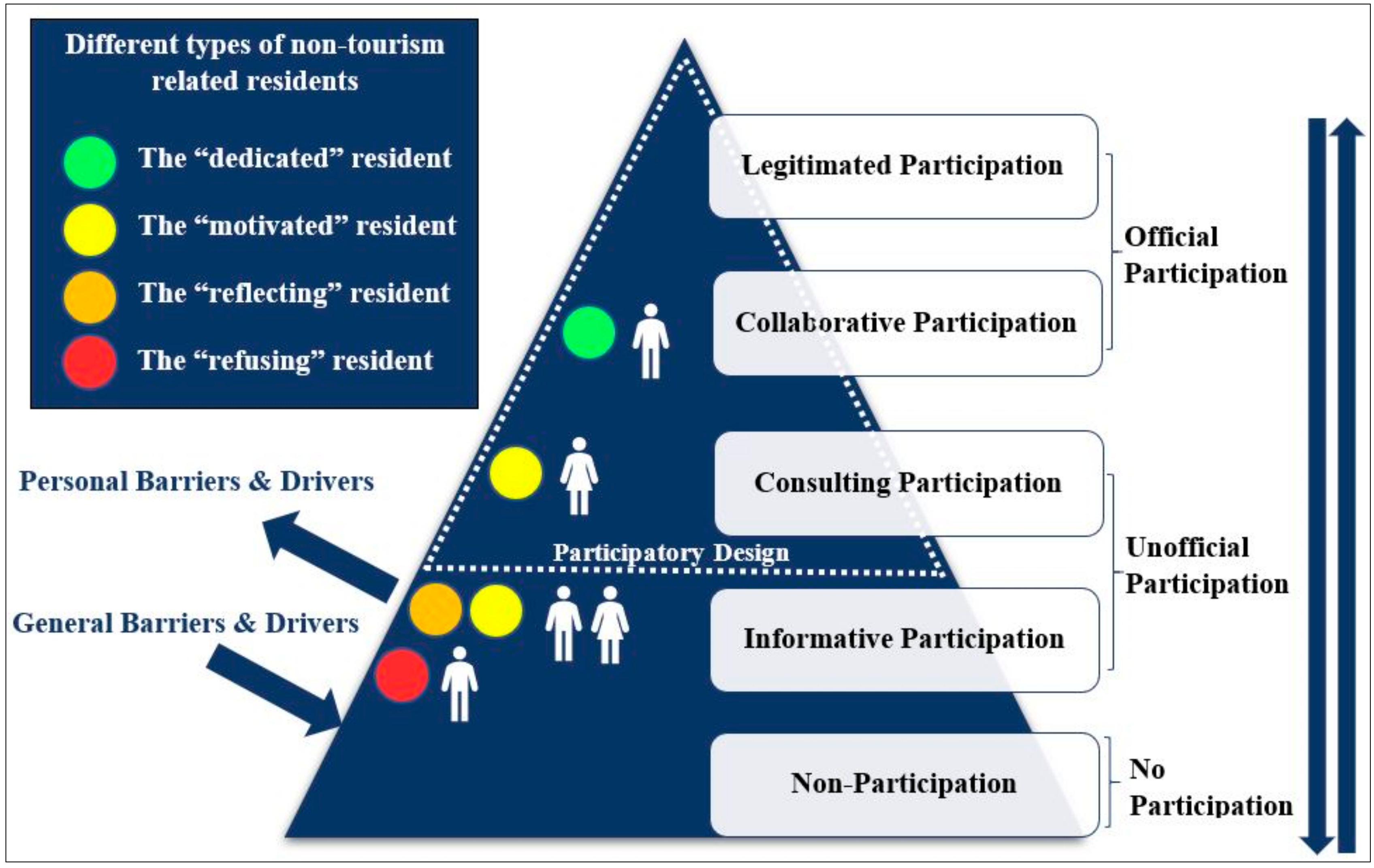

In the view of the previous results, a modified version of the pyramid of participation can be presented (see

Figure 4). This modified version now reflects different insights derived throughout this study.

The inward part of the pyramid is made up of a heterogenous group of people, which is represented by the different types of non-tourism related residents, including refusing, reflecting, motivated and dedicated residents. Thus, participants and potential participants dispose of a different level of past and current participation, a different aspiration for higher stages of the pyramid and generally a varying level of appreciation for non-tourism related residents’ participation in tourism development. Furthermore, these stakeholders are impacted by general barriers and drivers which act upon them from the outside. Yet, it has been shown that also personal barriers and drivers play an important role, affecting the people from the inside. Although the participants of the interviews named several specific barriers and drivers to non-tourism related residents’ participation in tourism development, most barriers and drivers named remain on a rather basic perspective. This may be because the interviewees are non-tourism related residents, and thus do not dispose of deep insights into participative processes of tourism development. As it was indicated earlier, in the literature such barriers and drivers are rather described for participation in tourism development in developing countries and in the context of community-based tourism Factors such as the basic educational level of the people or the overall underlying legal system [

7,

9] could not be revealed in this study, which is potentially due to the fact that barriers and drivers are often destination-specific and therefore play a deviating role in different destinations and contexts. Yet, many factors, for example residents’ place image [

22], psychological empowerment [

23] or positive and negative effects of tourism are clearly also relevant in the context of non-tourism related residents. Overall, the study did not reveal completely deviating barriers and drivers for non-tourism related residents in comparison to existing studies researching residents’ participation. Yet, it must be pointed out that it is not only important to give attention to different settings but also to different groups of stakeholders when researching residents’ participation in tourism development.

Switching between the pyramid’s stages of participation represents a reciprocal way as some people choose to participate on higher levels only once and go back to their original level. Unlike in other approaches (see

Table 1), these different levels are named in a neutral way since the study has not revealed that non-tourism related residents generally complain about low levels of participation or appraise them as inherently negative. Finally, the study revealed that none of the interviewees could be placed in the stage of

Non-Participation. This may be due to the fact that from the perspective of potential non-tourism related residents, participating in the study may has required at least a very basic interest in matters of tourism. Therefore, the participants were placed on higher levels. Yet, the level of Non-Participation is still included in the pyramid since the sample of this study only represents a small portion of all non-tourism related residents of the destination.

It was shown that economic benefits often represent the general rationale behind participation of stakeholders in tourism development [

6]. The participants of this study are not related to the tourism sector in terms of making their living from the tourism sector. Yet they acknowledged the economic importance and named different aspects that underline the public nature of tourism, wherefore tourism not only concerns tourism-related residents but all residents in a destination. In this regard, non-tourism related residents also appeared as users of touristic infrastructure and services. These results point out that from the perspective of non-tourism related residents, participating in tourism development can mean more than caring for a better holiday for potential visitors. It is also about shaping one’s own living environment and designing a better touristic infrastructure and offer, and thus improving the leisure opportunities for oneself. This clearly reflects the basic features and assumptions of PD, seeing the participants as potential users and thus also as active parts of the design process [

38,

39]. Of course, PD will only be able to set in if the participants dispose of such a perspective on participation in tourism development. In this regard, it also must be considered that it has been revealed that PD theoretically applies to active forms of participation [

37], which exceed the level of

Informative Participation. In the light of the modified pyramid of participation (see

Figure 4), PD therefore represents a way to make the transition from

Informative Participation to higher stages, which represents the transition from passive to active participation. This again points out that PD requires the participant to dispose of a complex and personally concerned view on participation in tourism development for making the effort to participate on higher levels.

The study has implications for future tourism development and the design of means of participation. The modified pyramid of participation underlined that it is important to regard participation of non-tourism related residents as a process and not as a state. Furthermore, the typology (see

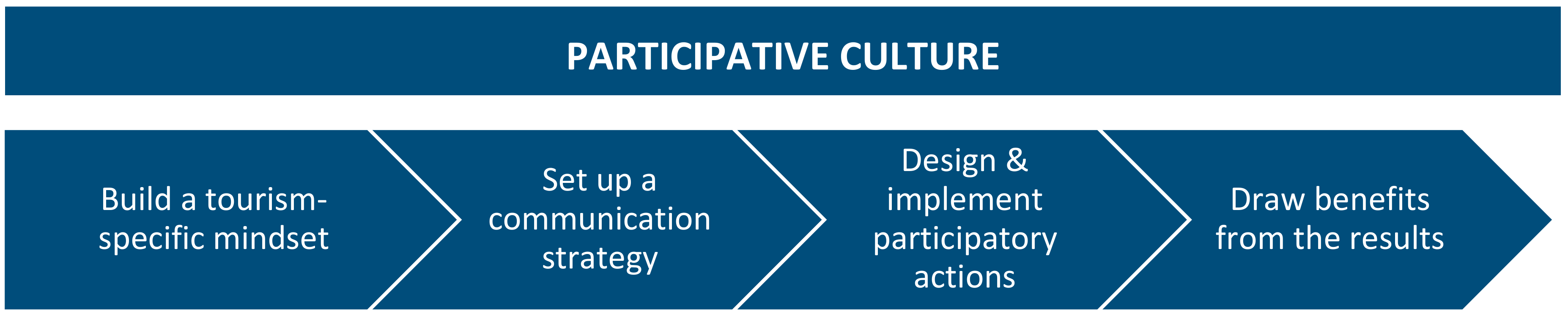

Figure 5) showed that different non-tourism related residents face participation differently. Practical actions must therefore consider all types of non-tourism related residents and their individual levels of participation. In this regard, the following figure summarizes the different phases of practical recommendations from this study. These phases must be seen in the light of a participative culture that can only be developed if all phases of actions are taken seriously.

Firstly, it is crucial to develop a participative mindset. It must be understood that tourism represents a public domain in many destinations. Officials, decision makers, tourism companies and institutions must understand that non-tourism related residents represent a capable and not inherently unwilling group of stakeholders in tourism development. Of course, it must be acknowledged that neither every non-tourism related resident is interested in participating in tourism development on a higher level nor, as indicated above, every non-tourism related resident is refusing to do so.

Secondly, non-tourism related residents must be convinced that participation can also mean improving the touristic and leisure infrastructure, resulting in enriching one’s own living environment, which may be used by the participants themselves. In this regard, triggering the appreciation for one’s place of living can represent an important feature of the communication strategy. Furthermore, potential participants must not only be equipped with basic information concerning tourism development but also with information on opportunities to participate in tourism development. It is also important to directly communicate that non-tourism related residents can contribute with their local expertise or even their knowledge of other destinations as some non-tourism related residents may not even be aware of their own capabilities. To make sure that all non-tourism related residents are able to receive the information needed, different communication channels, such as the local newspaper, publications, websites and social media, must be used.

Following a clear communication strategy, it is about the successful design and planning of different means of participation. Most importantly, a low-threshold access to such means must be ensured as tourism is not the daily business of non-tourism related residents. This requires orienting towards the individual characteristics of the potential participant. The refusing resident, for example, may only be interested in being informed properly. The reflecting residents must be triggered by situation-specific opportunities to participate and must be presented with clear benefits to do so, whereas the motivated resident can be prompted by participative options such as surveys or workshops. Regarding the dedicated resident, it is vital to ensure his or her ongoing level of participation.

The last phase may represent the phase with the most vital actions and decides whether the participation of non-tourism related residents will be having a lasting effect. In this regard, it is important to ensure an efficient and professional drawing of benefits from the results gained through different means of participation. This requires forwarding results to respective officials, institutions and decision-makers in order to ensure that such results and ideas can be put into practice. Besides this, it is also important to publish results and information in public media channels. Only if this is ensured, the participants and all other residents, who represent potential future participants, will be informed about the success and the results from means of participation.

Overall, it is worth pointing out again that the actions described above do of course not guarantee an immediate success. However, these actions help to establish a participative culture in the destination that does not inherently exclude any stakeholders from participation and sees all residents, either tourism-related or not, as promising and valuable parts of tourism development.

7. Conclusions

This study applied an adapted approach of the traditional view on participation in tourism development by looking at it from new perspectives. In this regard, a look into the academic literature showed that there is rather a superficial claim to involve all stakeholders in tourism development than looking at the process and patterns of such participation more in detail. As well, if such processes are described more detailed, it is mostly done with a focus on tourism in developing countries and community-based tourism. This study placed the focus on the nature of participation in a developed Alpine Destination to show that it is important to research participation in tourism development both in the context of developing and developed countries and concentrated on an under-researched group of stakeholders, namely non-tourism related residents. It was made an attempt to use PD as an underlying concept for participation in tourism development. With this theoretical concept, it was aimed to show that participation means more than promoting sustainable development or community-based tourism in order to achieve certain goals from an official perspective. PD rather underlines the fact that tourism represents a public domain that concerns all stakeholders of a destination and sees participants as active subjects and users who can also have a personal interest in participation. As the focus of this study was on the nature of participation, different ways of systematizing participation were derived from the literature. Overall, the study investigated how non-tourism related residents face the process of local participation in tourism development and what the main barriers and drivers are in this regard. For this, a typology, made up of four different types of non-tourism related residents was derived. Based on the results, a modified version of the pyramid of participation was set up for participation of non-tourism related residents, which is shaped by the different types of residents. It is also shaped by different barriers and drivers, both personal and general ones.

By approaching the field of research through a qualitative case-study, a holistic and internal view could be created, which would have been hard to achieve through a quantitative approach. Although the case-study could thus not come up with completely generalizable results for other destinations, there is great potential for future research to further investigate non-tourism related residents and the way how they face participation in tourism development. Thereby, the pyramid of participation set up in this study can be applied to other destinations and thus be amended and refined over time. Yet, it must be reminded that the case study was carried out in a destination where tourism plays an important role that has been further growing over the past years. The average length of stay, which is particularly high in cure clinics, also contributes to the fact that guests and tourism in general form a natural part of the everyday life in the destination of Bad Reichenhall. It is thus important to take a close look at the destination behind when applying the pyramid of participation to other case objects. Also, the typology and the barriers and drivers carved out in this study represent a connecting factor for future studies. Particularly, the drivers underline the existence of non-economic reasons for participation and support the evolving stream in the literature that researches participation in tourism from a non-economic perspective. A potential quantitative approach with a greater sample size seems to be possible in this regard as the results of this study were derived case-specific. Furthermore, future studies can pick up on the theoretical approach of using PD in the field of tourism development and thus see participants as users of touristic developments and tourism in general as a public domain. In this regard, PD may be a promising concept to be especially applied to the transition to the higher stages of participation. It needs more research to strengthen the position of PD in tourism literature and to develop specific practical measures in this regard.