Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Sustained Work Behavior: A Perspective of Playfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

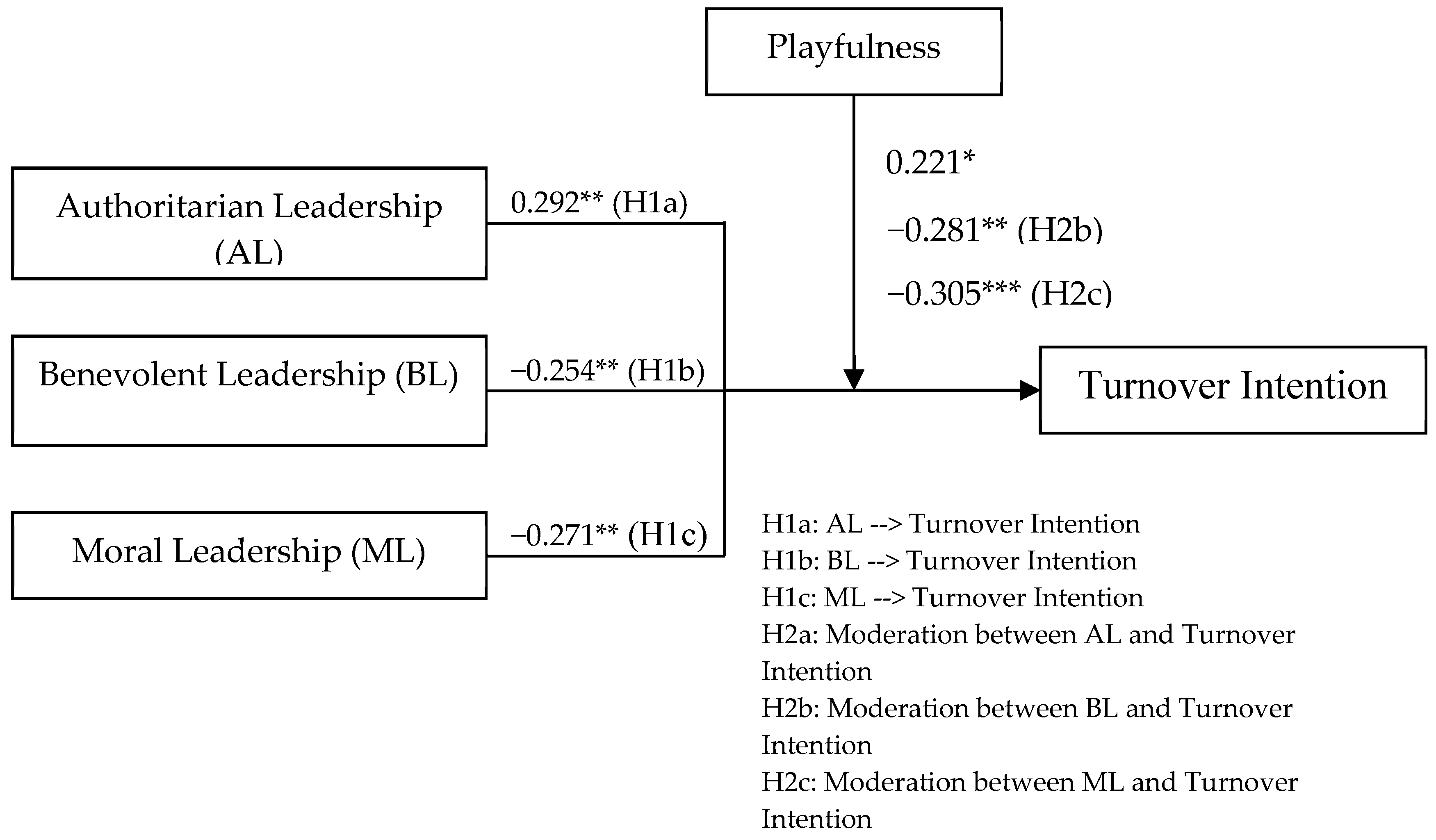

2.1. Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Turnover Intention

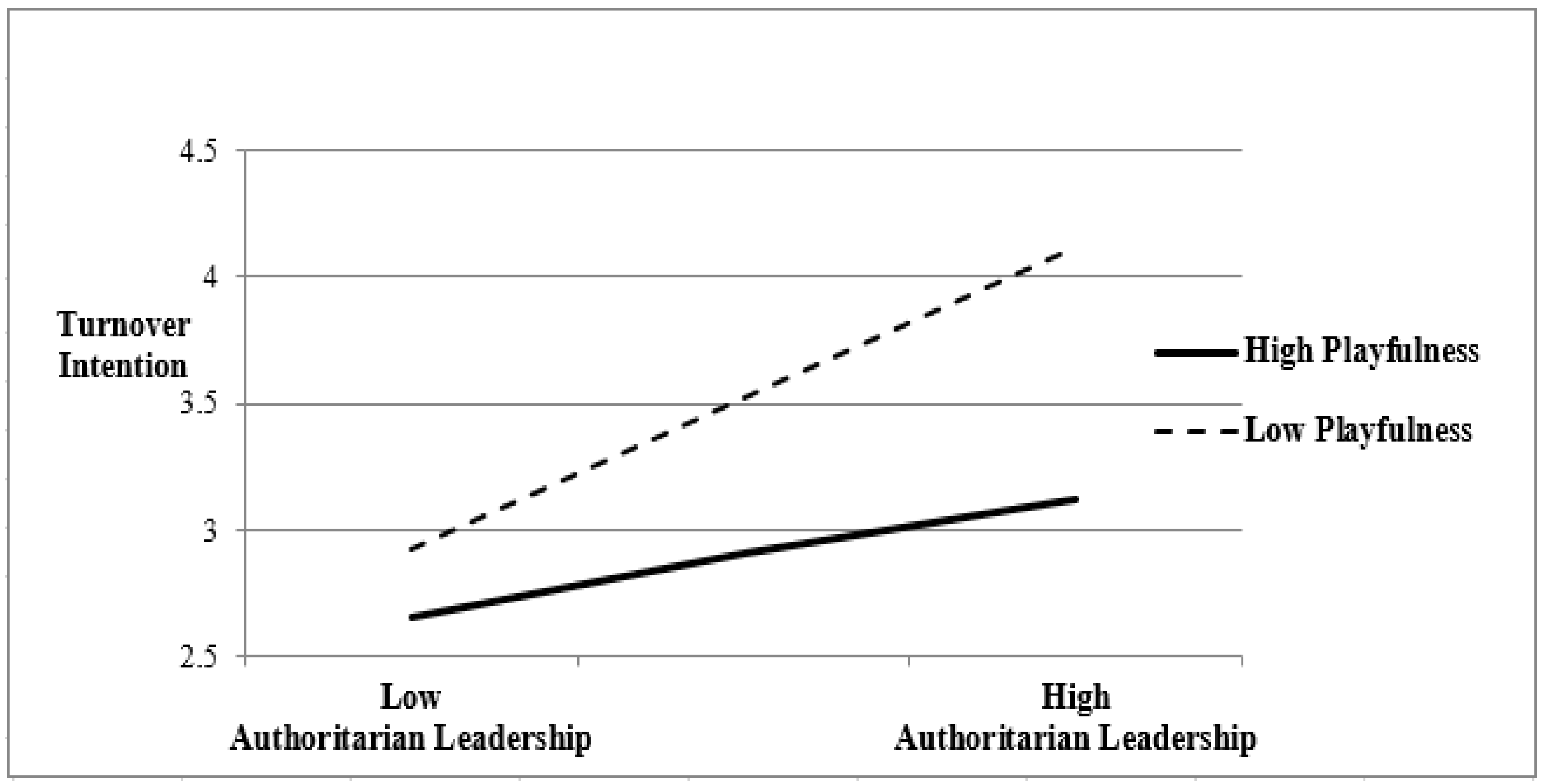

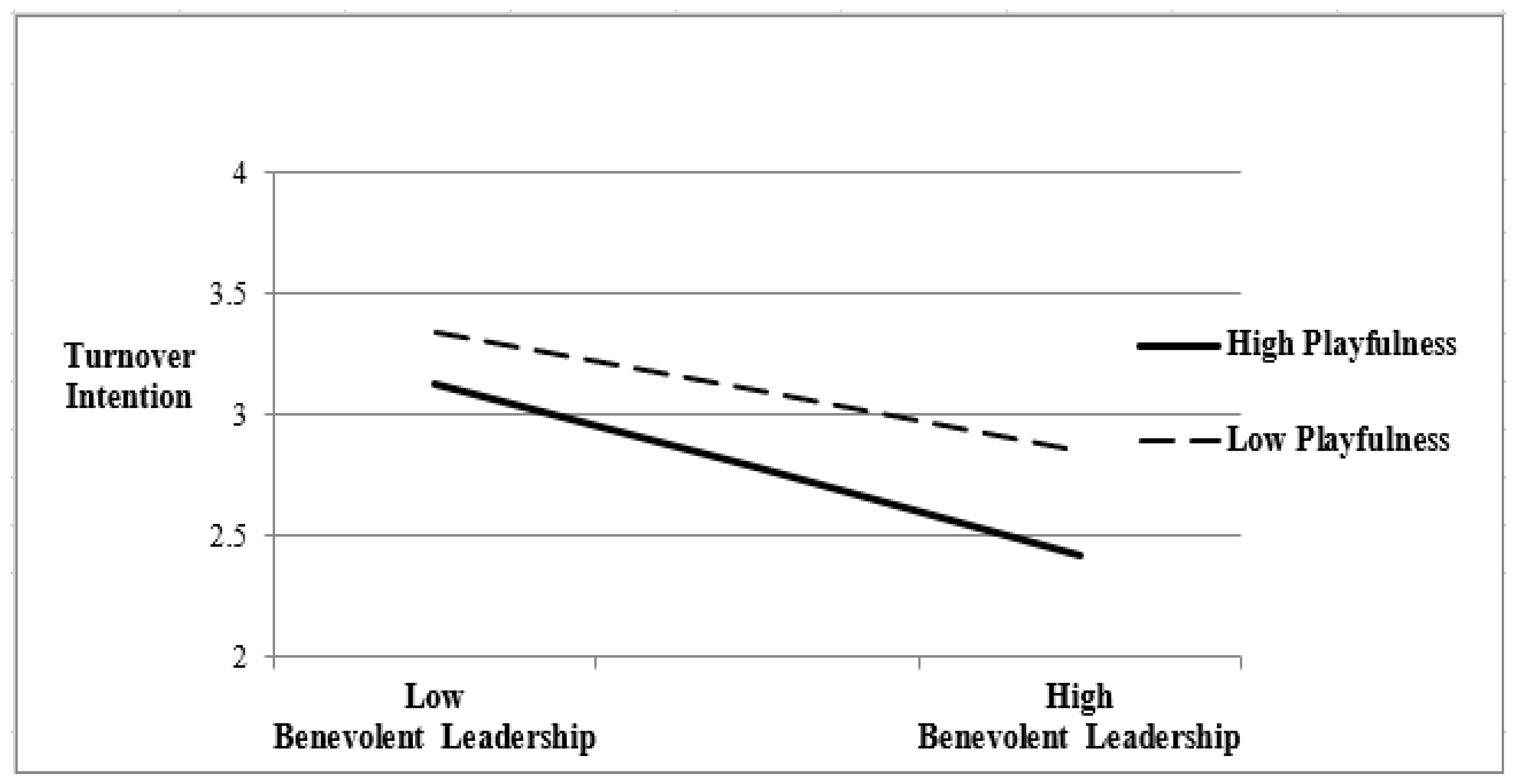

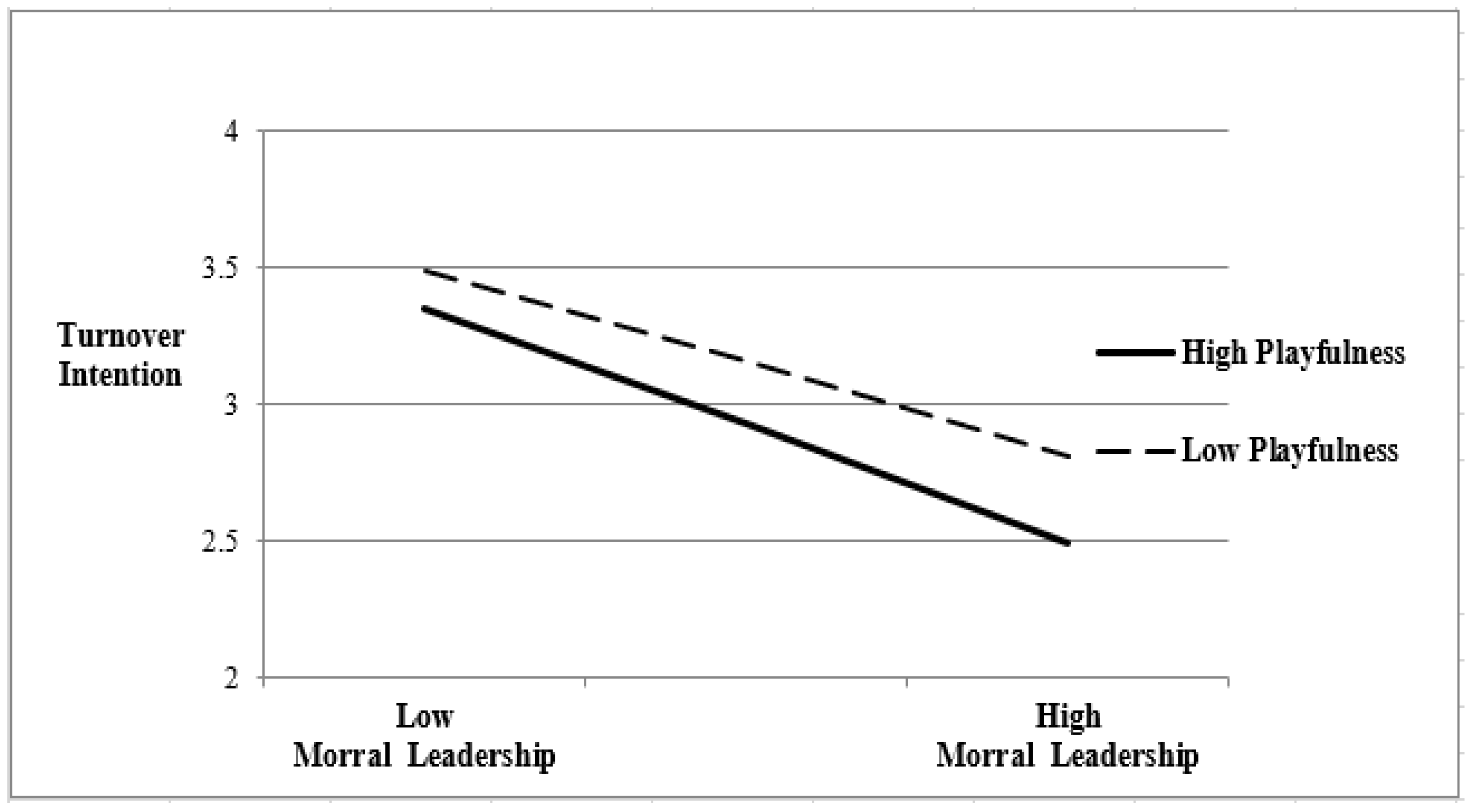

2.2. Moderating Effects of Playfulness

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Result

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaminakis, K.; Karantinou, K.; Koritos, C.; Gounaris, S. Hospitality servicescape effects on customer-employee interactions: A multilevel study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.E. The changing role of employees in service theory and practice: An interdisciplinary view. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.H.; Chiu, W.C.K.; Yu, P.L.H.; Cheng, K.; Tse, H.H.M. The effects of service climate and the effective leadership behaviour of supervisors on frontline employee service quality: A multi-level analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wu, Y.J.; Tsai, H.; Li, Y. Top Management Teams’ Characteristics and Strategic Decision-Making: A Mediation of Risk Perceptions and Mental Models. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoux-Nicolas, C.; Sovet, L.; Lhotellier, L.; Di Fabio, A.; Bernaud, J.-L. Perceived Work Conditions and Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Meaning of Work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.-S.; Chou, L.-F.; Wu, T.-Y.; Huang, M.-P.; Farh, J.-L. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 7, 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Cheng, B.-S. A Cultural Analysis of Paternalistic Leadership in Chinese Organizations. In Management and Organizations in the Chinese Context; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 84–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B.; Hong, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, Y. Paternalistic leadership and innovation: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.K. Confucian relationalism and social exchange. In Foundations of Chinese Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.-K. Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Game. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J.; Tsai, H.-T.; Yeh, S.-P. The Role of manager’s Locus of Control between perceived guanxi and leadership behavior in family Business. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2014, 72, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J.; Yuan, K.-S.; Yen, D.C.; Xu, T. Building up resources in the relationship between work–family conflict and burnout among firefighters: Moderators of guanxi and emotion regulation strategies. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitropaki, O.; Kark, R.; Mainemelis, C.; Lord, R.G. Leadership and followership identity processes: A multilevel review. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 104–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.C.; Egold, N.W.; Van Dick, R. Towards understanding the role of organizational identification in service settings: A multilevel study spanning leaders, service employees, and customers. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2012, 21, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Widowati, R.; Hu, D.-C.; Tasman, L. The mediating effect of psychological contract in the relationships between paternalistic leadership and turnover intention for foreign workers in Taiwan. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-Y.; Tsai, J.C.-A.; Chou, S.-T. Decomposing perceived playfulness: A contextual examination of two social networking sites. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, N.; Wu, Y.J. Does university playfulness climate matter? A testing of the mediation model of emotional labour. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2019, 56, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Su, F.; Cheng, D.; Wen, S. Multilevel Impacts of Transformational Leadership on Service Quality: Evidence From China. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Lin, M.; Wu, X. The trickle-down effect of servant leadership on frontline employee service behaviors and performance: A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.J.; Wu, Y.J. Innovative work behaviors, employee engagement, and surface acting: A delineation of supervisor-employee emotional contagion effects. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 3200–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, S.G. The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Pye, L.W.; Pye, M.W. Asian Power and Politics: The Cultural Dimensions of Authority; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jang, S.H.; Lee, S.Y. Paternalistic leadership and knowledge sharing with outsiders in emerging economies: Based on social exchange relations within the China context. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1094–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Tang, T.L.P.; Jiang, W. Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader–member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Driving employees to serve customers beyond their roles in the Vietnamese hospitality industry: The roles of paternalistic leadership and discretionary HR practices. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Huang, M.; Hu, Q.; Schminke, M.; Ju, D. Ethical leadership, but toward whom? How moral identity congruence shapes the ethical treatment of employees. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 1120–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A.T.; Bozorov, F.; Sung, S. Paternalistic Leadership and Innovative Behavior: Psychological Empowerment as a Mediator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-G. Linking leader authentic personality to employee voice behaviour: A multilevel mediation model of authentic leadership development. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huai, M.-Y.; Xie, Y.-H. Paternalistic leadership and employee voice in China: A dual process model. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R.T. Development and initial assessment of a short measure for adult playfulness: The SMAP. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, G. Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchover, S. The Relation between Teachers’ and Children’s Playfulness: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Wu, J.-J.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, Y.-T. Is playfulness a benefit to work? Empirical evidence of professionals in Taiwan. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2007, 39, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R.T.; Gander, F.; Bertenshaw, E.J.; Brauer, K. The Positive Relationships of Playfulness with Indicators of Health, Activity, and Physical Fitness. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, C.E.; Spector, P.E. Causes of employee turnover: A test of the Mobley, Griffeth, Hand, and Meglino model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, L.; Schiopoiu, A.B.; Mihai, M. Comparison of the leadership styles practiced by Romanian and Dutch SME owners. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2017, 6, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlea-Schiopoiu, A.; Rainey, S. Servant leader/Servant leadership. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., das Gupta, A., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2120–2126. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Authoritarian leadership | 2.72 | 0.82 | (0.833) | ||||

| 2. Benevolent leadership | 3.23 | 0.73 | −0.211 * | (0.892) | |||

| 3. Moral leadership | 3.66 | 0.68 | −0.236 ** | 0.268 ** | (0.925) | ||

| 4. Playfulness | 3.41 | 0.77 | −0.241 ** | 0.257 ** | 0.294 ** | (0.884) | |

| 5. Turnover intention | 2.91 | 0.92 | 0.281 ** | −0.232 ** | −0.264 *** | −0.0292 | (0.903) |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | NFI | IFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-factor model | 3413.16 | 461 | 7.40 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Five-factor model | 2499.57 | 475 | 5.26 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Single-factor model | 4764.82 | 483 | 9.87 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, C.-H.; Fang, C.-L.; Chao, R.-F.; Lin, S.-P. Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Sustained Work Behavior: A Perspective of Playfulness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236650

Fang C-H, Fang C-L, Chao R-F, Lin S-P. Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Sustained Work Behavior: A Perspective of Playfulness. Sustainability. 2019; 11(23):6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236650

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Ching-Han, Ching-Lin Fang, Ren-Fang Chao, and Shang-Ping Lin. 2019. "Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Sustained Work Behavior: A Perspective of Playfulness" Sustainability 11, no. 23: 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236650

APA StyleFang, C.-H., Fang, C.-L., Chao, R.-F., & Lin, S.-P. (2019). Paternalistic Leadership and Employees’ Sustained Work Behavior: A Perspective of Playfulness. Sustainability, 11(23), 6650. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236650