Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Focus Group Method

- The possibility of appointing a qualified facilitator to encourage interactions between the members present;

- The interaction between the participating members leads to complex debates that generate new results;

- Non-verbal communication regarding a concept that proves to be approached by organizations as a result of an imposition from the business environment;

- Sustainability is intensely debated by researchers, and so far, no concrete performance indicators and tools for implementation have been established. Therefore, the debates are appropriate to address this concept.

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Stages of Present Reserach

- Listing of the literature based on empirical experience, with qualitative research. Based on this inventory, we identified and structured: 2030 Agenda principles, sustainability objectives, sustainable development models, stakeholder engagement models in sustainable development. Based on these qualitative assessments, 15 important principles for organizational sustainability applicable to the automotive industry were mapped. These principles underpin the development of the sustainability model proposed in this paper.

- Analyzing focus group data, in which 33 employees were invited. This market research was conducted in order to identify the most important aspects of OS that should be included in the proposal of a new model. Three focus groups were made, each person being present just one time. Each focus group had a duration of 90 min and was coordinated by a facilitator/an expert (the expert was chosen from the categories: shareholders, manager, or general manager by the authors, according to the proven skills on the OS). There were 7 questions established for discussions, and 3 questions were established by each expert who coordinated the interviewed group. The sample consisted of all large (multinational) companies with branches in Romania.

- Using logical diagrams to describe the steps of the proposed model.

- Conducting 3 in-depth interviews to prevalidate the proposed model. The interviews were conducted with the three experts from point 2.

- Validating the proposed model within the largest automotive industry company in the Western Region of Romania.

- Evaluating and analyzing the results and suggesting future research.

2.4. Details of the Company Evaluated

2.5. Validating the Proposed Model

3. 2030 Agenda, Principles, and Objectives

- Universality: the area of application is universal; it refers to all countries and can be applied at any time.

- Leaving no one behind: the agenda supports anyone, no matter where they are and what the environmental conditions are.

- Interconnectedness and indivisibility: interconnection and indivisibility of its 17 SDGs to any entity.

- Inclusiveness: supporting the participation of any market segment, irrespective of race, ethnicity, identity, or interests.

- Multi-stakeholder partnerships: developing communication across multiple partnerships that facilitate the exchange of knowledge, experience, technology, and facilitate the use of organizational resources.

4. Theoretical Grounding

4.1. The Importance of Stakeholder Involvement in Organizational Sustainability

4.2. Methods and Tools for Sustainable Development

5. Results

6. Sustainability Model Proposed for the Automotive Industry

- (1)

- The understanding and assessment of organizational capacity for sustainable development—identifying, evaluating, and understanding the factors affecting the development of a program for launching sustainable development.

- (2)

- Evaluating the activities launched for sustainable development—identifying and evaluating the activities undertaken for the OS.

- (3)

- Generating the report of the evaluation—generating the report based upon the organizational assessment.

- (4)

- The action plan of the organization—developing an action plan to increase the likelihood of OS.

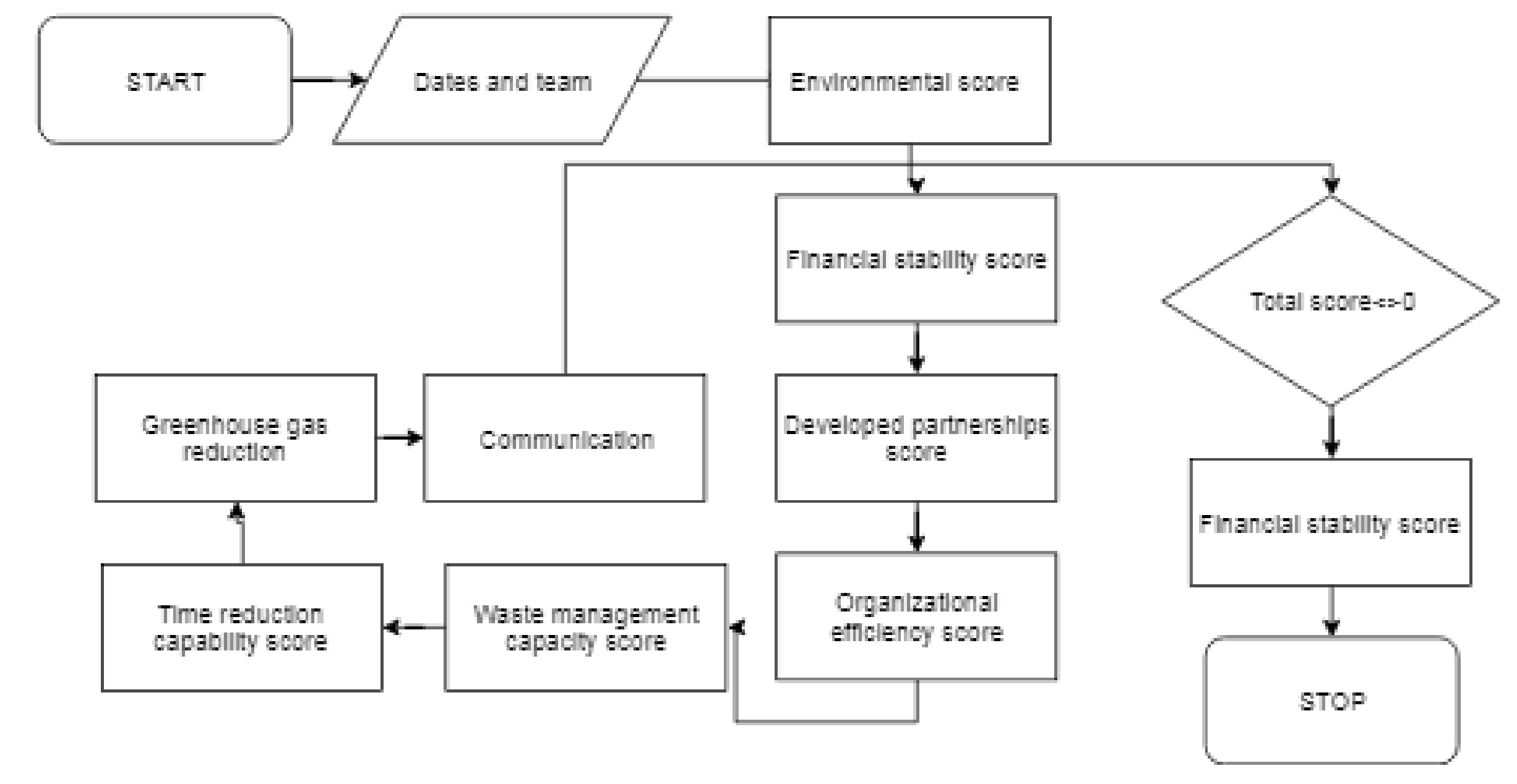

6.1. Stage of Understanding and Assessment of Organizational Capacity for Sustainable Development

6.2. Evaluating the Activities Launched for Sustainable Development

6.3. Generating the Report of the Evaluation

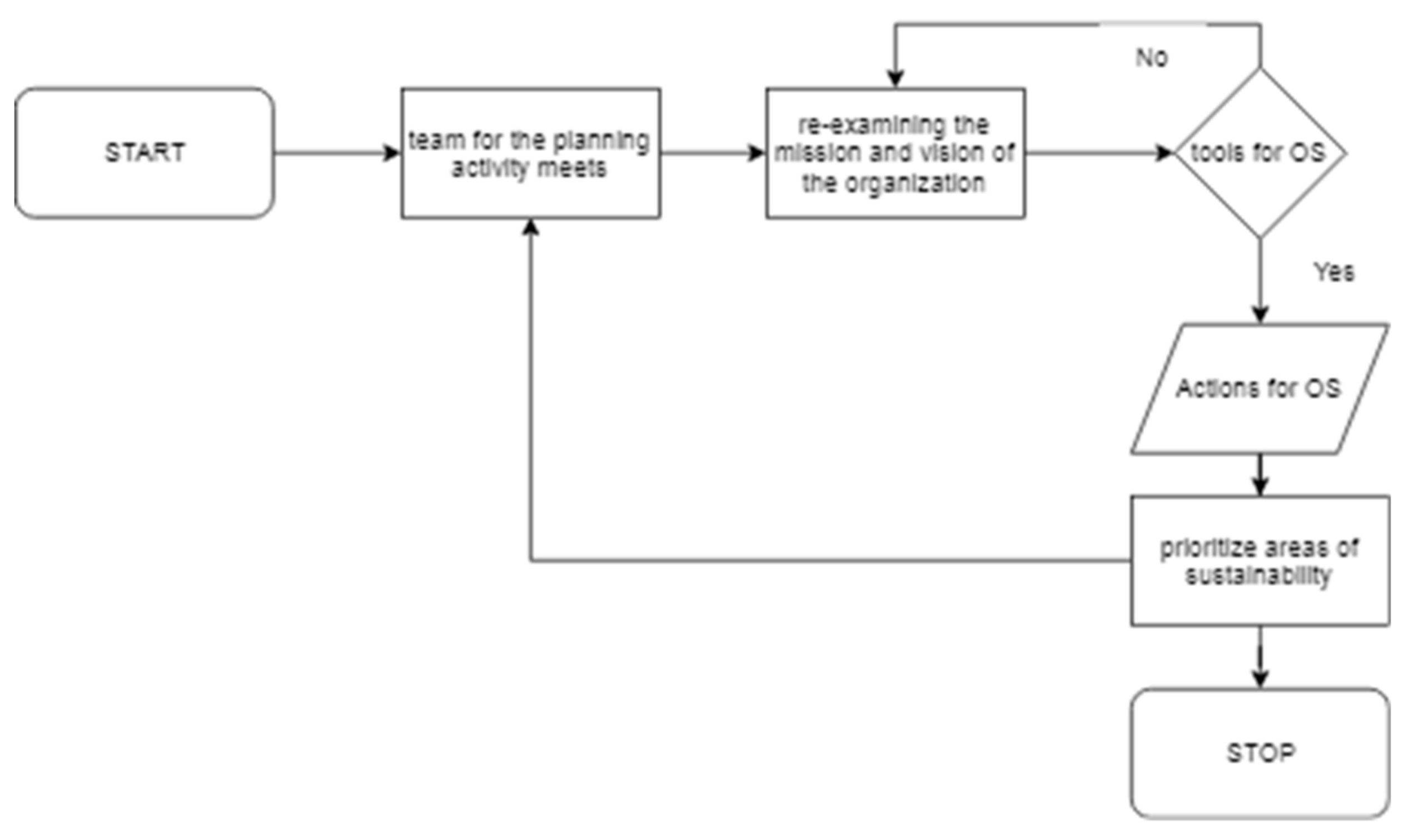

6.4. The Action Plan of the Organization

6.5. Case Study: A Large Multinational Company

7. Discussion

- Evaluating elements of strategic management (starting from vision, mission, to objectives) is important for proposing a new model [49];

- Appreciating the level of maturity of the company, strategic planning, and the stakeholders’ interest are important dimensions for organizational sustainability;

- The 15 proposed principles cover the 2030 Agenda principles, and they identify themselves with the objectives of the companies from the automotive industry;

- Stakeholder models show that the interests of OS are different, as shareholders should be interested directly in sustainability. Their direct interest could lead to improving financial results if we take into consideration a longer period of time;

- The three conducted focus groups with employees from the automotive industry, have highlighted that: over 80% of participants were aware of the sustainability concept, the training part was mainly done by self-education, the tools used for OS are numerous (ranging from implemented international standards to clean production tools such as lean), and the stakeholders target financial results;

- From the conducted focus groups, it can be concluded that most organizations are aware of organizational sustainability as long as it is required by environmental regulations (e.g., waste management) and ISO standards, which are the norm in the auto industry and in situations where a friendly behavior towards the environment is considered economically beneficial for the company;

- Another important aspect is the one related to the economic benefits. In the case of the OS approach within the organizations, economic benefits are usually recorded (decent work and economic growth; industry innovation and infrastructure; and responsible consumption and production; process and material losses reduction, increasing resource efficiency and customer satisfaction, cost reduction and increasing product quality, productivity improvement and company image improvement, et al.). In the event that these economic benefits would not exist, the interviewees appreciated that the organizational involvement would be minimal or lacking. The implications of organizations for sustainable practices exist, as long as there are economic benefits;

- The results obtained within the focus groups underly the knowledge development basis for the proposed sustainable development model;

- Validating the tool within one of the most important companies of the automotive industry has strengthened the correctness of the proposed logic and has helped make modifications related to: the number of indicators used for each domain. These indicators are taken over from the GRI type reporting of sustainability;

- For large multinational companies, the implementation and execution of the concept is usually done at the headquarters areas. That is why the decision to use a new model must be accompanied by a strong motivational driving force;

- The free use of a proposed model can be, for starters, a good motivational driving force for companies in the automotive field;

- For the multinational companies in the automotive field, the concept of sustainable development is a well-known one. The decisions of the implementation of the different concepts are made in headquarters, where the know-how is supported;

- Developing sustainable strategies is a priority for these companies;

- The homogeneity of the groups has led to expected results that outline the idea that these companies are open to aligning with international imperatives as long as they have an economic benefit;

- The barriers in implementing the proposed model are relative to the motivational factors and to the communication with the headquarters of the companies;

- The economic benefits are the imperatives that contribute to implementing the concept of sustainable development in organizations;

- The shareholders of multinational companies must be convinced of the economic benefits of OS.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cioca, L.-I.; Ivascu, L.; Rada, E.C.; Torretta, V.; Ionescu, G. Sustainable Development and Technological Impact on CO2 Reducing Conditions in Romania. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1637–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A. Towards sustainable development in industrial small and Medium-sized Enterprises: An energy sustainability approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, L.R.; de Jesus Lameira, V.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Pereira, F.N. Sustainability in the Brazilian heavy construction industry: An analysis of organizational practices. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4312–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.S.; Chen, S.H.; Hsu, C.W.; Hu, A.H. Identifying strategic factors of the implantation CSR in the airline industry: The case of Asia-Pacific airlines. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7762–7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Torres, S.; Rey-Garcia, M.; Albareda-Vivo, L. Effective Disclosure in the Fast-Fashion Industry: From Sustainability Reporting to Action. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.A.D.S.; Francisco, A.C.D. Organizational Sustainability Practices: A Study of the Firms Listed by the Corporate Sustainability Index. Sustainability 2018, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics, Statistical Data. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/ (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Patón-Romero, J.D.; Baldassarre, M.T.; Rodríguez, M.; Piattini, M. Application of ISO 14000 to Information Technology Governance and Management. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2019, 65, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, P.; Marques, R. On the economic performance of the waste sector. A literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 106, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tăucean, I.M.; Tămășilă, M.; Ivascu, L.; Miclea, Ș.; Negruț, M. Integrating Sustainability and Lean: SLIM Method and Enterprise Game Proposed. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogardus, E. The group interview. J. Appl. Sociol. 1926, 10, 372–382. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.; Fisk, M.; Kendall, P. The Focused Interview: A Report of the Bureau of Applied Social Research; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Health Illn. 1994, 16, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skop, E. The Methodological Potential of Focus Groups in Population Geography. Popul. Space Place 2006, 12, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, B.F.; Sevegnani, F.; Almeida, C.; Agostinho, F.; Moreno, R.R.; Liu, G.G. Five sector sustainability model: A proposal for assessing sustainability of production systems. Ecol. Model. J. 2019, 406, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säynäjoki, E.S.; Heinonen, J.; Junnila, S. The power of urban planning on environmental sustainability: A focus group study in Finland. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6622–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opazo-Basáez, M.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O. Uncovering productivity gains of digital and green servitization: Implications from the automotive industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Olalla, A.; Avilés-Palacios, C. Integrating Sustainability in Organisations: An Activity-Based Sustainability Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A Review of Corporate Sustainability Reporting Tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amui, L.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Kannan, D. Sustainability as a Dynamic Organizational Capability: A Systematic Review and a Future Agenda toward a Sustainable Transition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviera-Puig, A.; Gómez-Navarro, T.; García-Melón, M.; García-Martínez, G. Assessing the Communication Quality of CSR Reports. A Case Study on Four Spanish Food Companies. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11010–11031. [Google Scholar]

- Falle, S.; Rauter, R.; Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R.J. Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in Smes: Findings from an Austrian Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.Y.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, K.S.; Beltagui, A.; Riedel, J.C.K.H. The PSO Triangle: Designing Product, Service and Organisation to Create Value. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2009, 29, 468–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerisch, J.; Freeman, R.E.; Schaltegger, S. Applying Stakeholder Theory in Sustainability Management Links, Similarities, Dissimilarities, and a Conceptual Framework. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, S.; Sheth, J. Developing the Sustainable Edge. Lead. Lead. 2017, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poponi, S.; Colantoni, A.; Cividino, S.R.; Mosconi, E.M. The Stakeholders’ Perspective within the B Corp Certification for a Circular Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamkovaia, M.; Arcila, M.; Cardoso Martins, F.; Izquierdo, A. Sustainable Development of Coastal Food Services. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canh, N.T.; Liem, N.T.; Thu, P.A.; Khuong, N.V. The Impact of Innovation on the Firm Performance and Corporate Social Responsibility of Vietnamese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinski, D.; Meredith, J.; Kirwan, K. A Comprehensive Review of Full Cost Accounting Methods and Their Applicability to the Automotive Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108 Pt A, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, J.; Shi, G.; Li, J.; Lu, C. Laboratory-Based Investigation into Stress Corrosion Cracking of Cable Bolts. Materials 2019, 12, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Belleghem, B.; van den Heede, P.; van Tittelboom, K.; de Belie, N. Quantification of the Service Life Extension and Environmental Benefit of Chloride Exposed Self-Healing Concrete. Materials 2017, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, T.B.; Caeiro, S. Meta-performance Evaluation of Sustainability Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z. Corporate sustainability: Theoretical and Integrated Strategic Imperative and Pragmatic Approach. J. Bus. Inq. 2017, 16, 60–87. [Google Scholar]

- Olugu, E.U.; Wong, K.Y.; Shaharoun, A.M. Development of Key Performance Measures for the Automobile Green Supply Chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, B. A Systematic Approach to Environmental Priority Strategies in Product Development (EPS): Version 2000-General System Characteristics; Centre for Environmental Assessment of Products and Material Systems: Goteborg, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Conte, A. A Streamlined LCA Framework to Support Early Decision Making in Vehicle Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoît, C.; Norris, G.A.; Valdivia, S.; Ciroth, A.; Moberg, A.; Bos, U.; Prakash, S.; Ugaya, C.; Beck, T. The Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products: Just in Time! Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subic, A.; Koopmans, L. Global Green Car Learning Clusters. Int. J. Veh. Des. 2010, 53, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, P.O.; Olomolaiye, P.O. Development of Sustainable Assessment Criteria for Building Materials Selection. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2012, 19, 666–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravossis, K.G.; Kapsalis, V.C.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Xouleis, T.G. Development of a Holistic Assessment Framework for Industrial Organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, P.; Bargozin, H.; Pourafshary, P. Management of Implementation of Nanotechnology in Upstream Oil Industry: An Analytic Hierarchy Process Analysis. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2018, 140, 052908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rayash, A.; Dincer, I. Sustainability assessment of energy systems: A novel integrated model. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1098–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.B.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Rezaei, J. Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Xi, B.; Ren, J.; Ren, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Dong, L. Multi-criteria sustainability assessment of urban sludge treatment technologies: Method and case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriantiatsaholiniaina, L.A.; Kouikoglou, V.S.; Phillis, Y.A. Evaluating strategies for sustainable development: Fuzzy logic reasoning and sensitivity analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coss, S.; Rebillard, C.; Verda, V.; Le Corre, O. Sustainability assessment of energy services using complex multi-layer system models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Ferro, C.; Høgevold, N.; Padin, C.; Varela, J.C.S.; Sarstedt, M. Framing the triple bottom line approach: Direct and mediation effects between economic, social and environmental elements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 972–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zha, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Liang, L. Data envelopment analysis for sustainability evaluation in China: Tackling the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 275, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Shuai, C.; Jiao, L.; Shen, L. An adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) approach for measuring country sustainability performance. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 65, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Johansson, B.; Lyons, K.W.; Sriram, R.D.; Ameta, G. Simulation andanalysis for sustainable product development. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ 2018, 613–614, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, A.; Qattawi, A.; Omar, M.; Shan, D. Design for sustainability inautomotive industry: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1845–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, J.W. Global sustainability and key needs in future automotive design. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5414–5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Lujia, F.; Mayyas, A.; Omar, M.A.; Al-Hammadi, Y.; Al Saleh, S. Production energy optimization using low dynamic programming, a decisionsupport tool for sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation. Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, L.C.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Schierbeck, J. Characterisation of social impactsin LCA. Part 2: Implementation in six company case studies. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efroymson, R.A.; Dale, V.H.; Kline, K.L.; McBride, A.C.; Bielicki, J.M.; Smith, R.L.; Parish, E.S.; Schweizer, P.E.; Shaw, D.M. Environmental indicators of biofuel sustainability: What about context? Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekener-Petersen, E.; Moberg, A. Potential hotspots identified by social LCAe Part 2: Reflections on a study of a complex product. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Group 1 | Focus Group 2 | Focus Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Company 1—electronic control modules, vacuum pumps, accelerator pedals, and electric power control modules | Company 1—car tires | Company 1—multifunction steering wheel switches, light-block switches, climate control systems, and center console control elements |

| Company 2—injection components, electronics, car wiring | Company 2—headlamps, fog lamps, additional stop lamps, and truck headlights | Company 2—assemblies, engine components |

| Company 3—car seats and interior elements | Company 3—automation, control systems | Company 3—anti-vibration components |

| Company 4—car wiring | Company 4—car wiring | Company 4—tires, electronic components |

| Company 5—steering wheels, seat belts | Company 5—trailer components | Company 5—rubber and plastic components |

| Company 6—electric cables | Company 6—car ceiling components | Company 6—car wiring |

| Company 7—car lighting | Company 7—cable protection | Company 7—electric systems, cables |

| Company 8—chair control systems, integrated window modules | Company 8—hydraulic braking equipment | Company 8—car ornaments |

| Company 9—upholstery | Company 9—chassis solutions, steering, powertrain, torsion bars | Company 9—high precision components and systems for engines, transmission, and chassis applications |

| Company 10—electric cables | Company 10—automotive control units, electronics, research center | Company 10—electric systems, cables |

| Company 11—alternators | Company 11—sintered mechanical parts, and spark plugs | Company 11—radiators, condensers and air conditioning systems, compressors, exhaust |

| Facilitator—electronic modules (general manager) | Facilitator—rubber and plastic components (general shareholder) | Facilitator—high precision components and systems for engines (manager) |

| Common Questions Discussed in the Three Focus Groups | Questions Discussed in Focus Group 1 | Questions Discussed in Focus Group 2 | Questions Discussed in Focus Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing the OS concept Sustainability is important for the strategic practices of the organization 5 tools used for OS Training employees regarding OS 3 objectives targeted by OS 3 benefits after adopting OS3 disadvantages of OS | Periodicity of reporting sustainability Main organizational advantage OS results within the organization | Interest of stakeholders in OS Shareholder OS approval OS reporting costs | Appreciation of the company’s maturity level Strategic planning Stakeholder interests |

| Responsibility | Domain | Number of Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | financial stability | 10 |

| developed partnerships | 5 | |

| organizational efficiency | 8 | |

| capacity to reduce production time | 7 | |

| Social | communication and human resource | 20 |

| Environment | environment | 15 |

| waste management capacity | 15 | |

| greenhouse gas reduction | 5 |

| No. | Principle | Implication | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Interests of stakeholders | Putting into operation activities that are in line with stakeholders’ strategic plans. | SDG1, SDG12 |

| S2 | Reduction of toxicity | Reducing the toxic impact of the workplace on employees. | SDG4, SDG5 |

| S3 | Reducing operator overload | Reducing operator overload on production jobs | |

| S4 | Reducing resources | Reducing process losses contributes to improving financial results. | SDG9, SDG12 |

| S5 | Time efficiency | Increasing production capacity as a result of reducing activities time | SDG9, SDG12 |

| S6 | Reducing waiting time | The company has to reduce its waiting time to improve its production capacity. | SDG9, SDG12 |

| S7 | Monitoring fixed costs | Reducing fixed costs contributes to the efficiency of the production activities | SDG12, SDG17 |

| S8 | Stakeholder engagement in strategic decisions | Strategic planning should take into account the functions of sustainable development | SDG6, SDG8, SDG17 |

| S9 | Supporting community activities | Company involvement in society contributes to improving living conditions | SDG2, SDG3, SDG16 |

| S10 | Training human resources | By training human resources, the company’s performance level is improved. | SDG4, SDG5 |

| S11 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | CSR actions improve employee wellbeing and improve public image | SDG 1, SDG10 |

| S12 | Increasing recycling capacity | Reducing the amount of waste generated contributes to reducing the organizational impact on the environment | SDG14, SDG15 |

| S13 | Increasing the capacity of the reuse, remanufacturing, reconditioning | Waste management functions generate added value for the organization | SDG7, SDG12 |

| S14 | Reducing energy consumption | Increasing the capacity to generate energy and reducing energy consumption contribute to protecting the environment | SDG9, SDG13 |

| S15 | Greenhouse gas reduction | The implication of the company în this activity leads to reducing pollution to the environment. | SDG11, SDG13 |

| Authors | Model Description |

|---|---|

| Hoerisch et al., 2014 [27] | The research identifies three challenges related to the interaction of stakeholder and OS relations: strengthening the specific interests of stakeholders’ sustainable development, creating mutual sustainability interests based on this particular interest, and empowering stakeholders to act as intermediaries for nature and sustainable development. Three interdependent mechanisms are suggested to help solve interconnection: education, regulation, and the creation of sustainable values with stakeholders. |

| Apte and Sheth, 2017 [28] | Stakeholders have a direct, indirect, or enabling impact. The stakeholders that have a direct impact are: consumers, customers, and employees; stakeholders with an indirect impact are: government, organizations, and media. Investors, suppliers, and communities are tangential to OS principles. |

| Poponi et al., 2019 [29] | Stakeholders reinforce their ability to engage in sustainable development based on incentives and financial opportunities. |

| Iamkovaia et al., 2019 [30] | Stakeholders share their influences on putting the OS into operation in two large categories: direct, from the inside of the company and indirect, from the outside the company. |

| Canh et al., 2019 [31] | This study evaluates stakeholders’ interests according to the performance of the employed actions. Research has been carried out on a sample of Vietnamese production firms over the period 2011–2013. |

| Silva et al., 2019 [32] | This research distinguishes stakeholders and their expectations with regard to their various roles in the process of evaluating and controlling sustainability performance: standards-setting factors, information providers, affected stakeholders, decision-makers, and recipients. The analysis of individual roles reveals that stakeholders’ expectations are rarely specifically taken into account. |

| No. | Question Discussed | Key Actions Identified |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowing the OS concept | 89% of the participants know the concept and have applied it within the company they work for. |

| 2 | Sustainability is important for the strategic practices of the organization | 95% replied in the affirmative and consider sustainability as an integral part of the vision and mission. |

| 3 | 5 tools used for OS | ISO Standard, LCSA, RECP, problem solving, sustainable indicators. |

| 4 | Training employees regarding OS | 47% of participants were trained on the principles, objectives, and tools of the OS, and the rest were self-educated. |

| 5 | 3 objectives targeted by OS | Decent work and economic growth (69.23%); industry innovation and infrastructure (64.62%); and responsible consumption and production (61.54%) (multiple answer). |

| 6 | 3 benefits after adopting OS | Improving the quality of processes and operations (55%), standardizing activities (23%), teamwork (76%). |

| 7 | 3 disadvantages of OS | Cost, time, unprepared employees. |

| 8 | Periodicity of reporting sustainability | In 70% of cases, reporting is done annually, whereas in 30% of cases, it is done once every two years. |

| 9 | Main organizational advantage | The following advantages have been mentioned: strategic planning in line with OS objectives (40%), motivation of human resources (30%), and reduction of production waste (30%). |

| 10 | OS results within the organization | Over 70% of the first group’s members responded that it had visible results within the organization. |

| No. | Question Discussed | Key Actions Identified |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowing the OS concept | 81% of the participants know the concept, have studied it, and have applied it within the company they work for. |

| 2 | Sustainability is important for the strategic practices of the organization | 84% replied in the affirmative and consider OS as being an important direction for the company. |

| 3 | 5 tools used for OS | Lean manufacturing (Kanban, 5S), ISO Standard, LCSA, problem solving, sustainable indicators. |

| 4 | Training employees regarding OS | 30% were trained, whilst 70% were self-educated. |

| 5 | 3 objectives targeted by OS | Process and Material Losses Reduction, Increasing Resource Efficiency and Customer Satisfaction (83.08%), Cost Reduction and Increasing Product Quality (80.00%), and Productivity Improvement and Company Image Improvement (78.46%). |

| 6 | 3 benefits after adopting OS | Work standardization (70%), improving public image (20%), visual management (10%). |

| 7 | 3 disadvantages of OS | Cost, training employees, and the infrastructure related to information technology. |

| 8 | Interest of stakeholders in OS | Shareholders from within the company are involved directly or indirectly in OS. |

| 9 | Shareholder OS approval | In 85% of cases, shareholders approve of OS and take its principles into consideration when defining strategic planning. |

| 10 | OS reporting costs | Expenditures are covered by internal funds and are supported by shareholders. |

| No. | Question Discussed | Key Actions Identified |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Knowing the OS concept | 95% of the participants know the concept, and 81% have applied it within the company they work for, whilst 13% apply it partially. |

| 2 | Sustainability is important for the strategic practices of the organization | 80% replied in the affirmative and consider sustainability as an integral part of the vision and mission. |

| 3 | 5 tools used for OS | ISO Standard, sustainable indicators, LCSA, environment-related tools, Waste Management |

| 4 | Training employees regarding OS | The majority of employees, 83%, were self-educated. The organization does not have resources for training. |

| 5 | 3 objectives targeted by OS | Improving the activity processes (71%), attracting new collaborators (89%), improving public image (54%). |

| 6 | 3 benefits after adopting OS | Improving the quality of processes and operations (75%), increasing recycling capacity (53%), increasing employees’ interest in the company. |

| 7 | 3 disadvantages of OS | Lack of reporting required by legislation, lack of information and ambiguity triggered by the lack of indicators for evaluation, internationally endorsed. |

| 8 | Appreciation of the company’s maturity level | Companies have reached the maturity level regarding organizational activity. |

| 9 | Strategic planning | In 91% of cases, strategic planning takes OS objectives into consideration. |

| 10 | Stakeholder interests | Stakeholder interests are partially aligned with OS objectives. In 65% of statements, shareholders support investments in OS. |

| No. | Principle | Phase of Implementation | Focus Group 1 | Focus Group 2 | Focus Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Interests of stakeholders | 1 | x | x | x |

| S2 | Reduction of toxicity | 2 | x | ||

| S3 | Reducing operator overload | 2 | x | x | x |

| S4 | Reducing resources | 2 | x | x | x |

| S5 | Time efficiency | 2 | x | x | |

| S6 | Reducing waiting time | 2 | x | x | x |

| S7 | Monitoring fixed costs | 2 | x | ||

| S8 | Stakeholder engagement in strategic decisions | 1 | x | x | x |

| S9 | Supporting community activities | 2 | x | x | x |

| S10 | Training human resources | 2 | x | x | x |

| S11 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | 2 | x | x | x |

| S12 | Increasing recycling capacity | 2 | x | x | |

| S13 | Increasing the capacity of the reuse, remanufacturing, reconditioning | 2 | x | x | |

| S14 | Reducing energy consumption | 2 | x | x | x |

| S15 | Greenhouse gas reduction | 2 | x | x | x |

| Step | Implication | The Situation within the Organization |

|---|---|---|

| 1a/1b | The vision, mission, and organizational goals are identified. They can be found on the company’s website. | The company’s vision integrates OS elements stating that “The company aims to become a world leader in the automotive industry, based on the principles of durability.” The mission includes key elements, ranging from employees to caring for the community, customers, and suppliers. |

| 1c | The importance of sustainability for the company | Within the discussions with the shareholders, a disposition towards the OS is noticed if improved financial results are also achieved. |

| 1d | Status of previous reporting of sustainability | A check was carried out to see whether there was a previous sustainability report. There was an earlier report. Sustainability was reported between 2010–2019. The way of reporting differs. In the first years, a qualitative type assessment was carried out on the basis of evaluating the internal and external environment, whereas the GRI reporting was used in the last three years. The report is retained, and the team for the next stage is identified as being formed by the leaders of the production, development, warehouse, sales, financial-accounting, and human resource teams. |

| 2a. | Data from the company is collected. | All data has been identified, and there is a representative for each domain. |

| 2b | Environment domain € | A score of E = 4.0 is obtained. This value places the company above the average implications in the protection of the environment; however, actions for improvement are still necessary. |

| 2c | Financial stability domain (FS) | A score of FS = 3.8 is obtained. This score is average, meaning that financial stability can be improved. |

| 2d | Developed partnerships domain (P) | A score of P = 5.4 is obtained. As can be observed for the development of partnerships, the company obtains an above average score, being proof of the good relationship with its partners. |

| 2e | Organizational efficiency domain (EO) | A score of EO = 5.8 is obtained. Organizational efficiency is proven by the organization, the score being positioned in the upper half of the total implementation (towards the maximum of 7). |

| 2f | Waste management capacity domain (WM) | A score of WM = 6.4 is obtained. The capacity for waste management obtains a maximum score, which means that this company has good waste management. |

| 2g | Capacity to reduce production time domain (TR) | A score of TR = 4.4 is obtained. The capacity to reduce time positions the company slightly above the average maximum value of the domain. |

| 2h | Greenhouse gas reduction (GHG) domain | A score of GHG = 3.0 is obtained. The value of the domain is lower, being evidence of generating a large quantity of greenhouse gases. |

| 2i | Communication domain (C) | A score of C = 4.0 is obtained. Communication is positioned within the domains that need to be improved, due to the score obtained. |

| 2j | The total score of OS is calculated (TOS) | TOS = 4.6. This obtained score, above average, highlights the fact that the organization has to improve some of its domains to reach the maximum value of 7. |

| 3a, 3b | The team meets for the planning activity. | The team was reunited, and the mission was reformulated by adding elements related to equal opportunity at the workplace and ethics in promoting human resources. |

| 3c | The proposed tools for implementing sustainable development are examined. | The tools used for implementing sustainable development were examined, and it was revealed that the following were used: 5S, Kanban, Kaizen, RCEP, problem solving, and waste management. |

| 3d | The elements that need to be maintained, eliminated, or adapted are determined. | The elements that need to be maintained, eliminated, or adapted are determined. It is shown that communication needs to be intensified within the organization. |

| 3e | The sustainability domains are prioritized. | The sustainability domains are prioritized, with the domain of “organizational efficiency” being established as the most important. |

| 3f | The action plan is transcribed. | The action plan is transcribed and aligned with the specificity of the organization. A new report was obtained, which will be implemented within the organization. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cioca, L.-I.; Ivascu, L.; Turi, A.; Artene, A.; Găman, G.A. Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226447

Cioca L-I, Ivascu L, Turi A, Artene A, Găman GA. Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226447

Chicago/Turabian StyleCioca, Lucian-Ionel, Larisa Ivascu, Attila Turi, Alin Artene, and George Artur Găman. 2019. "Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226447

APA StyleCioca, L.-I., Ivascu, L., Turi, A., Artene, A., & Găman, G. A. (2019). Sustainable Development Model for the Automotive Industry. Sustainability, 11(22), 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226447