Land Conflict Management through the Implementation of the National Land Policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evolution and Elements of the National Land Policy Implementation in Tanzania

3. Materials and Methods

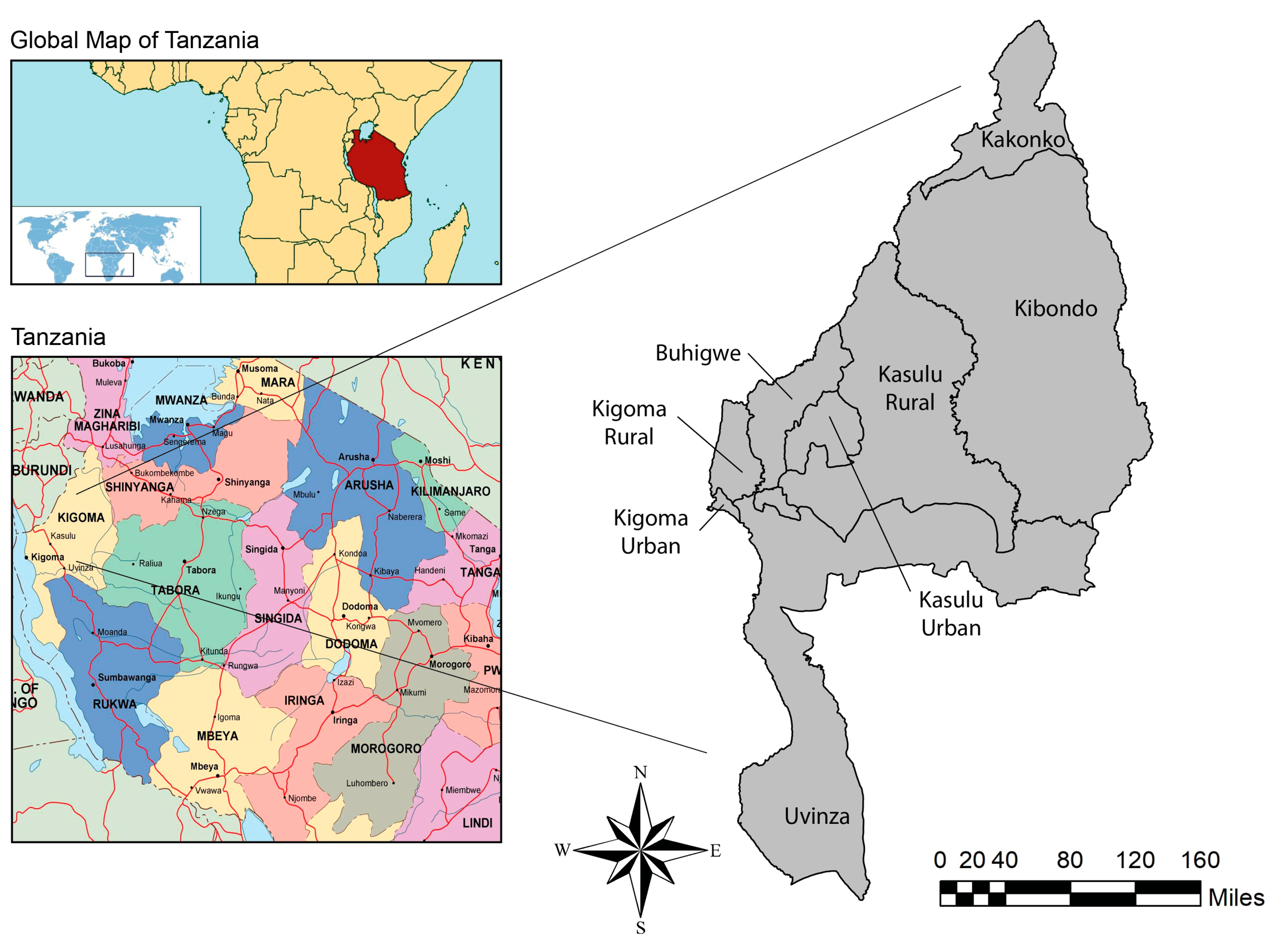

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Sampling Procedures and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

4.2. Gender, Land Titling, and Participation in Land Issues

4.3. Frequency and Factors Associated with Land Conflicts in Rural Areas

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Verburg, P.H.; Crossman, N.; Ellis, E.C.; Heinimann, A.; Hostert, P.; Mertz, O.; Nagendra, H.; Sikor, T.; Erb, K.-H.; Golubiewski, N.; et al. Land system science and sustainable development of the earth system: A global land project perspective. Anthropocene 2015, 12, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzelli, S. Land resources in the Alps and instruments supporting their sustainable management as a matter of regional environmental governance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 14, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedertscheider, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Erb, K.-H. Exploring the effects of drastic institutional and socio-economic changes on land system dynamics in Germany between 1883 and 2007. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberl, H. Competition for land: A sociometabolic perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S.; Chamberlin, J.; Headey, D.D. Land pressures, the evolution of farming systems, and development strategies in Africa: A synthesis. Food Policy 2014, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangora, M.M. Shifting Cultivation, Wood Use and Deforestation Attributes of Tobacco Farming in Urambo District, Tanzania. Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Msuya, D.G. Farming systems and crop-livestock land use consensus. Tanzanian perspectives. Open J. Ecol. 2013, 3, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mwamfupe, D. Persistence of Farmer-Herder Conflicts in Tanzania. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2015, 5, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, M. Looking Back, Looking Ahead—Land, Agriculture and Society in East Africa: A Festschrift for Kjell Havnevik; NAI: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015; ISBN 978-91-7106-774-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J. Securing Community Land and Resource Rights in Africa: A Guide to Legal Reform and Best Practices; Fern: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 978-1-906607-33-3. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Tanzania 2013; OECD Investment Policy Reviews; OECD: Paris, France, 2013; ISBN 978-92-64-20433-1. [Google Scholar]

- Shivji, I.G. Land Tenure problems and Reforms in Tanzania. In Proceedings of the Sub-Regional Workshop for East Africa on Land Tenure Issues in Natural Resource Management, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 11–15 March 1996. [Google Scholar]

- The United Republic of Tanzania (URT). National Land Policy, 2nd ed.; The Ministry of Lands and Human Settlements: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1997.

- The United Republic of Tanzania (URT). Land Act of 1999; Government Printers: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 1999.

- Knight, R.S. Statutory Recognition of Customary Land Rights in Africa: An Investigation into Best Practices for Lawmaking and Implementation; FAO Legislative Study; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-92-5-106728-4. [Google Scholar]

- John, P.; Kabote, S.J. Land Governance and Conflict Management in Tanzania: Institutional Capacity and Policy-Legal Framework Challenges. AJRD 2017, 5, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, S. Land-access systems in peri-urban areas in Tanzania: Perspectives from Actors. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.A.; Collin, M.; Deininger, K.; Dercon, S.; Sandefur, J.; Zeitlin, A. The Price of Empowerment: Experimental Evidence on Land Titling in Tanzania; Working Paper No. 369; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kironde, J.M.L. Improving Land Sector Governance in Africa: The Case of Tanzania. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Land Governance in Support of the MDGs: Responding to New Challenges, Washington, DC, USA, 9–10 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Noe, C.; Richard, Y.M.K. Wildlife Protection, Community Participation in Conservation, and (Dis) Empowerment in Southern Tanzania. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntaine, M.T.; Hamilton, S.E.; Millones, M. Titling community land to prevent deforestation: An evaluation of a best-case program in Morona-Santiago, Ecuador. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 33, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Republic of Tanzania (URT). The United Republic of Tanzania: Economic Survey 2017; Ministry of Finance and Planning: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2018.

- Kaswamila, A.L.; Songorwa, A.N. Participatory land-use planning and conservation in northern Tanzania rangelands. Afr. J. Ecol. 2009, 47, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigbu, U.E.; Schopf, A.; de Vries, W.T.; Masum, F.; Mabikke, S.; Antonio, D.; Espinoza, J. Combining land-use planning and tenure security: A tenure responsive land-use planning approach for developing countries. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1622–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, L. Registering Rural Rights: Village Land Titling in Tanzania, 2008–2017. Innovations for Successful Societies, Princeton University. Available online: http://succefulsocieties.princeton.edu/ (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- John Walwa, W. Land use plans in Tanzania: Repertoires of domination or solutions to rising farmer-herder conflicts? J. East. Afr. Stud. 2017, 11, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoi, L. Land Conflicts and the Livelihood of Pastoral Maasai Women in Kilosa District of Morogoro, Tanzania in Kilosa District of Morogoro, Tanzania. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, I. Democracy and Land Conflicts in Tanzania: The Case of Pastoralists versus Peasants. Tanzan. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Donge, J.K. Legal insecurity and land conflicts in Mgeta, Uluguru Mountains, Tanzania. Africa 1993, 63, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongpin, P. Refugees in Tanzania—Asset or Burden? J. Dev. Soc. Transform. 2008, 5, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Selod, H.; Burns, A. The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8213-8758-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gwaleba, M.J.; Masum, F. Participation of Informal Settlers in Participatory Land Use Planning Project in Pursuit of Tenure Security. Urban Forum 2018, 29, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Holden, S.; Lund, C.; Sjaastad, E. Formalisation of land rights: Some empirical evidence from Mali, Niger and South Africa. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massay, G.E. Adjudication of Land Cases in Tanzania: A Bird Eye Overview of the District Land and Housing Tribunal. Open Univ. Law J. 2013, 4, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Pintea, L.; Bauer, M.E.; Bolstad, P.V.; Pusey, A. Matching Multiscale Remote Sensing Data to Interdisciplinary Conservation Needs: The Case of Chimpanzees in Western Tanzania. In Proceedings of the Pecora 15/Land Satellite Information IV/ISPRS Commission I/FIEOS Conference on Integrated Remote Sensing at the Global, Regional and Local Scale, Denver, CO, USA, 10–15 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sulle, E.; Nelson, F. Biofuels, Land Access and Rural Livelihoods in Tanzania; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84369-749-7. [Google Scholar]

- The United Republic of Tanzania. 2012 Population and Housing Census: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas; National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance and Planning: Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania; Office of Chief Government Statistician, President’s Office, Finance, Economy and Development Planning: Zanzibar, Tanzania; Government Printers: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2013.

- Whitaker, B.E. Refugees in Western Tanzania: The Distribution of Burdens and Benefits among Local Hosts. J. Refug. Stud. 2002, 15, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, M. The lack of refugee burden-sharing in Tanzania: Tragic effects. Afr. Focus 2009, 22, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirui, P.; Mwaruvie, D.J. The Dilemma of Hosting Refugees: A Focus on the Insecurity in North-Eastern Kenya. Int. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy Toft, M. The Myth of the Borderless World: Refugees and Repatriation Policy. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2007, 24, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codjoe, S.N.A.; Quartey, P.; Tagoe, C.A.; Reed, H.E. Perceptions of the Impact of Refugees on Host Communities: The Case of Liberian Refugees in Ghana. Int. Migr. Integr. 2013, 14, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. Environmental Conflict Between Refugee and Host Communities. J. Peace Res. 2005, 42, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeny, M. Improving Access to Land and strengthening Women’s land rights in Africa. In Proceedings of the Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 8–11 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L. The Impact of Environmental Degradation on Refugee-Host Relations: A Case Study from Tanzania; New Issues in Refugee Research, Research Paper No. 151; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Magawa, G.L.; Hansungule, M. Unlocking the Dilemmas: Women’s Land Rights in Tanzania. J. Law Crim. Justice 2018, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.A.; Deininger, K.; Goldstein, M. Environmental and gender impacts of land tenure regularization in Africa: Pilot evidence from Rwanda. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Clinch, J.P.; O’Neill, E. Accounting for transaction costs in planning policy evaluation. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Clinch, J.P.; O’Neill, E. Timing and distributional aspects of transaction costs in Transferable Development Rights programmes. Habitat Int. 2018, 75, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rap, E. The Practices and Politics of Making Policy: Irrigation Management Transfer in Mexico. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 506–531. [Google Scholar]

- Batley, R. The Politics of Service Delivery Reform. Dev. Chang. 2004, 35, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juknelienė, D.; Valčiukienė, J.; Atkocevičienė, V. Assessment of regulation of legal relations of territorial planning: A case study in Lithuania. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulle, A. Result-Based Management in the Public Sector: A Decade of Experience for the Tanzanian Executive Agencies. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2011, 4, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzo, R.G. This Is My Grand Pa’s Land: Land, and Development Projects and Evictions along Morogoro Highway, Tanzania. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Emanuel, M.; Ndimbwa, T. Traditional Mechanisms of Resolving Conflicts over Land Resource: A Case of Gorowa Community in Northern Tanzania. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Siebert, R.; Barkmann, T. Sustainability in Land Management: An Analysis of Stakeholder Perceptions in Rural Northern Germany. Sustainability 2015, 7, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaro, D.N. Land for Agriculture in Tanzania: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Land Soc. 2014, 1, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, B.; Lin, Y. Industrial land development in urban villages in China: A property rights perspective. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Tang, B. Institutional barriers to redevelopment of urban villages in China: A transaction cost perspective. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biitir, S.B.; Nara, B.B.; Ameyaw, S. Integrating decentralised land administration systems with traditional land governance institutions in Ghana: Policy and praxis. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, B. Land Conflicts: A Practical Guide to Dealing with Land Disputes; GTZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-00-023940-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ubink, J.M.; Hoekema, A.J.; Assies, W.J. Legalising Land Rights: Local Practices, State Responses and Tenure Security in Africa, Asia and Latin America; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 978-90-8728-056-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sundet, G. The Politics of Land in Tanzania. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nuhu, S. Peri-Urban Land Governance in Developing Countries: Understanding the Role, Interaction and Power Relation among Actors in Tanzania. Urban Forum 2019, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.S. Theory and Practice of Public Administration in Southeast Asia: Traditions, Directions, and Impacts. Int. J. Public Adm. 2007, 30, 1297–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, S.; Clinch, J.P.; O’Neill, E. Impact-based planning evaluation: Advancing normative criteria for policy analysis. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Districts | District Population | Households (HH) | Proportion to Size | Expected Sample Size of HH | Actual Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buhigwe District | 245,342 | 40,890 | 19% | 145 | 160 |

| Kigoma Rural District | 211,566 | 35,261 | 17% | 125 | 192 |

| Kasulu District | 425,794 | 70,966 | 34% | 252 | 215 |

| Uvinza District | 383,640 | 63,940 | 30% | 227 | 183 |

| Total | 1,266,342 | 211,057 | 100% | 749 | 750 |

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Total n (%) | Odds Ratio | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possessing land titles | ||||||

| Yes | 73 (80.2) | 18 (19.8) | 91 (100) | 0.578 | 0.0139 | 0.363–0.921 |

| No | 421 (64) | 238 (36) | 659 (100) | |||

| Owning surveyed land | ||||||

| Yes | 172 (53) | 153 (47) | 325 (100) | 0.495 | 0.0681 | 0.363–0.676 |

| No | 295 (69) | 130 (31) | 425 (100) | |||

| Engaging in land-use planning | ||||||

| Yes | 149 (56) | 118 (44) | 267 (100) | 0.655 | 0.0066 | 0.655–0.901 |

| No | 318 (66) | 165 (34) | 483 (100) | |||

| Participating in land issues | ||||||

| Every time | 187 (61) | 121 (39) | 308 (100) | 0.894 | 0.4641 | 0.656–1.220 |

| Few times | 280 (63) | 162 (37) | 442 (100) | |||

| Performing socio-economic activities | ||||||

| Farming | 264 (63) | 155 (37) | 419 (100) | 0.936 | 0.7111 | 0.649–1.346 |

| Herding | 131 (64.5) | 72 (35.5) | 203 (100) | |||

| Designation | Number of Officials Required | Number of Officials Present n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical planner | 10 | 4 (40) |

| Land officer | 10 | 5 (50) |

| Land assistant | 10 | 0 (0) |

| Valuation officer | 9 | 5 (50) |

| Land surveyor | 10 | 4 (40) |

| Total | 49 | 18 (37) |

| Districts | Number of Villages | Villages with Land-Use Plans | Villages without Land-Use Plans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kigoma Rural District | 46 | 11 (24) | 35 (76) |

| Kasulu District | 62 | 1 (0) | 61 (100) |

| Uvinza District | 61 | 25 (40) | 36 (60) |

| Kibondo District | 50 | 0 (0) | 50 (100) |

| Kakonko District | 44 | 0 (0) | 44 (100) |

| Buhigwe District | 45 | 4 (9) | 41 (91) |

| Total | 308 | 41 (13) | 267 (87) |

| Statements | Most Frequent | Frequent | Non-Frequent | Neutral | No Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conflicts between individuals owning lands | 16.1% | 16.3% | 63.8% | 3.1% | 0.7% |

| Conflicts between communities and investors | 7.2% | 12.8% | 77.9% | 1.6% | 0.5% |

| Conflicts between communities and state | 29.5% | 31.1% | 36.2% | 2.9% | 0.3% |

| Conflicts between communities | 25.6% | 42.1% | 28.3% | 2.9% | 1.1% |

| Factors | Experienced Conflict Yes, n (%) | Experienced Conflict No, n (%) | Total | AOR | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possessing land title | 65 (71.4) | 26 (28.6) | 91 (100) | 1.384 | 0.233 | 0.811–2.36 |

| Owning surveyed land | 212 (65.2) | 113 (34.8) | 325 (100) | 0.896 | 0.535 | 0.633–1.269 |

| Availability of land-use plans | 186 (69.7) | 81 (30.3) | 267 (100) | 1.419 | 0.043 | 1.01–1.993 |

| Presence of immigrants | 294 (71.5) | 117 (28.5) | 411 (100) | 1.963 | 0.000 | 1.441–2.673 |

| Shifting cultivation | 458 (65.1) | 245 (34.9) | 703 (100) | 1.378 | 0.308 | 0.744–2.554 |

| Purchased land | 319 (65) | 172 (35) | 491 (100) | 0.864 | 0.793 | 0.289–2.577 |

| Government-allocated land | 66 (63) | 39 (37) | 105 (100) | 0.825 | 0.742 | 0.262–2.599 |

| Inherited land | 87 (63.5) | 50 (36.5) | 137(100) | 0.757 | 0.629 | 0.244–2.347 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubakula, G.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C. Land Conflict Management through the Implementation of the National Land Policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226315

Rubakula G, Wang Z, Wei C. Land Conflict Management through the Implementation of the National Land Policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma Region. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226315

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubakula, Gelas, Zhanqi Wang, and Chao Wei. 2019. "Land Conflict Management through the Implementation of the National Land Policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma Region" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226315

APA StyleRubakula, G., Wang, Z., & Wei, C. (2019). Land Conflict Management through the Implementation of the National Land Policy in Tanzania: Evidence from Kigoma Region. Sustainability, 11(22), 6315. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226315