Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE)

2.2. Attribute Selection and Experimental Design

2.3. Data Collection and Survey

2.4. Model Specification

3. Results

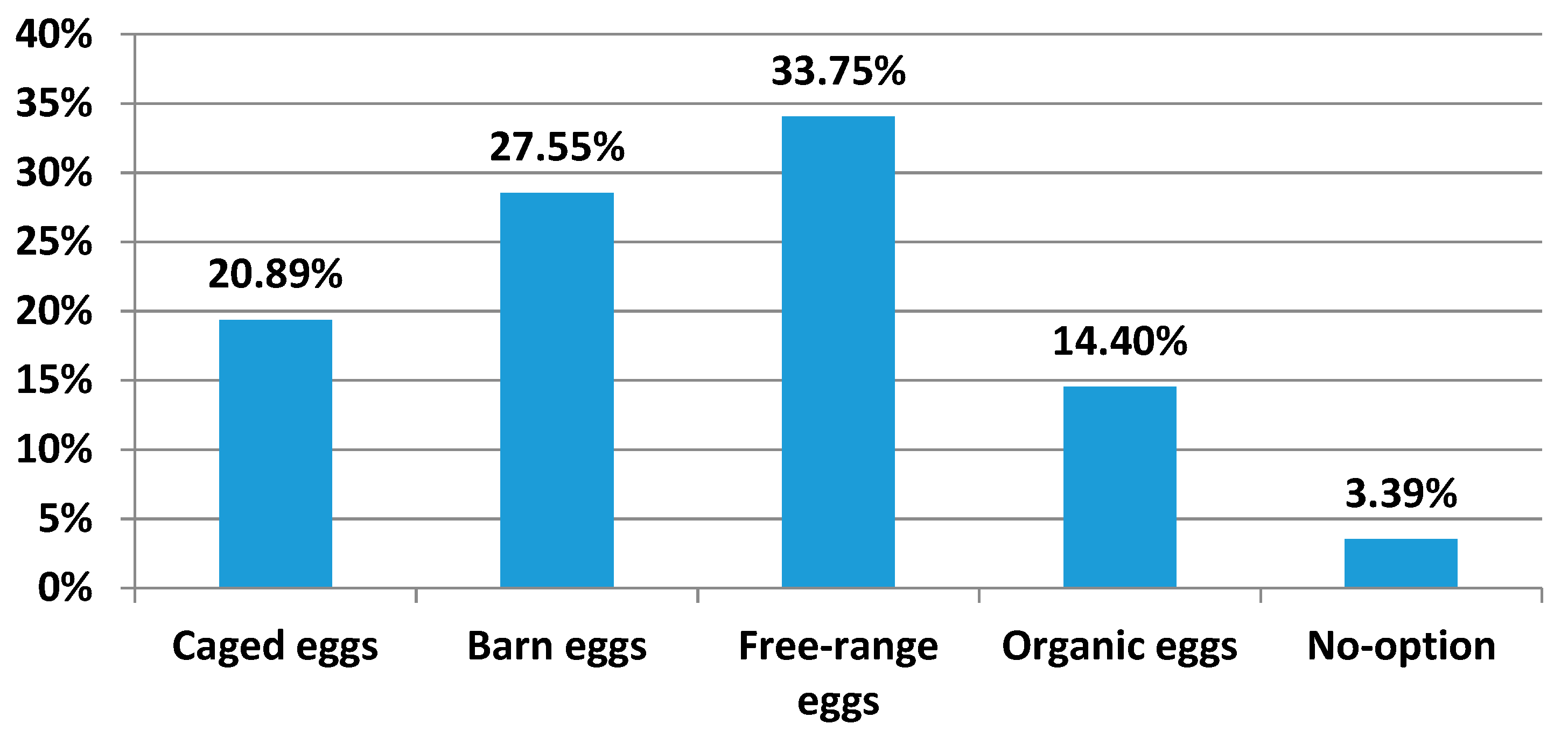

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Discrete Choice Experiment Results

3.2. Importance of Egg Attributes and Types: A Random Parameter Logit (RPL) Model

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | Human ingenuity will ensure that we do not make the Earth unlivable. a |

| 2 | We are approaching the limit of the number of people the Earth can support. (item removed) |

| 3 | The Earth has plenty of natural resources if we just learn how to develop them. a (item removed) |

| 4 | The Earth is like a spaceship with very limited room and resources. (item removed) |

| 5 | Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature. |

| 6 | Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. |

| 7 | Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. a |

| 8 | Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. a |

| 9 | Humans are seriously abusing the environment. |

| 10 | When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences. |

| 11 | Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature. a |

| 12 | If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. |

| 13 | The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. |

| 14 | The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated. a |

| 15 | The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations. a |

| 16 | In order to achieve sustainable development, a more balanced economy is required, accompanied by more controlled industrial growth. |

Appendix B

| 1 | It is morally wrong to hunt wild animals just for sport. |

| 2 | I do not think that there is anything wrong with using animals in medical research. a |

| 3 | I think it is perfectly acceptable for cattle and hogs to be raised for human consumption. a |

| 4 | Basically, humans have the right to use animals as we see fit. a |

| 5 | I sometimes get upset when I see wild animals in cages at zoos. |

| 6 | Breeding animals for their skins is a legitimate use of animals. a |

| 7 | Some aspects of biology can only be learned through dissecting preserved animals such as cats. a |

| 8 | It does not seem right that animals are used in cultural festivals. |

| 9 | The use of animals such as rabbits for testing the safety of cosmetics and household products is unnecessary and should be stopped. |

| 10 | I agree with the use of animals for work. a |

| 11 | I do not agree with improving animals’ health or resistance to disease through genetic modification. (item removed) |

Appendix C

| Items | Mean Score | SD | Factor Loading | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Ecocentric attitude towards the environment | 31.87% | |||

| 9. Humans are seriously abusing the environment. | 5.91 | 1.41 | 0.82 | |

| 10. When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences. | 5.78 | 1.40 | 0.79 | |

| 6. Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist. | 5.78 | 1.45 | 0.73 | |

| 12. If things continue on their present course, we will soon experience a major ecological catastrophe. | 5.51 | 1.46 | 0.73 | |

| 13. The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | 5.53 | 1.35 | 0.71 | |

| 5. Despite our special abilities, humans are still subject to the laws of nature. | 5.61 | 1.38 | 0.70 | |

| 16. In order to achieve sustainable development, a more balanced economy is required, accompanied by more controlled industrial growth. | 5.38 | 1.36 | 0.66 | |

| Factor 2: Anthropocentric attitude towards the environment | 21.57% | |||

| 7. Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs. a | 6.55 | 1.81 | 0.74 | |

| 15. The balance of nature is strong enough to cope with the impacts of modern industrial nations. a | 6.52 | 1.81 | 0.73 | |

| 11. Humans were meant to rule over the rest of nature. a | 6.85 | 1.89 | 0.72 | |

| 14. The so-called “ecological crisis” facing humankind has been greatly exaggerated. a | 6.47 | 1.86 | 0.71 | |

| 8. Humans will eventually learn enough about how nature works to be able to control it. a | 4.56 | 1.68 | 0.59 | |

| 1. Human ingenuity will ensure that we do not make the Earth unlivable. a | 5.68 | 1.76 | 0.47 | |

| Average mean | 5.86 | 0.84 | ||

| Overall 13 item scores b | 76.21 | 10.93 | ||

Appendix D

| Items | Mean Score | SD | Factor Loading | Variance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Consumers’ attitudes toward animal use | 35.55% | |||

| 1. It is morally wrong to hunt wild animals just for sport. | 5.47 | 1.81 | 0.71 | |

| 2. I do not think that there is anything wrong with using animals in medical research. a | 6.08 | 1.88 | 0.70 | |

| 3. I think it is perfectly acceptable for cattle and hogs to be raised for human consumption. a | 5.10 | 1.59 | 0.64 | |

| 4. Basically, humans have the right to use animals as we see fit. a | 6.74 | 1.80 | 0.61 | |

| 5. I sometimes get upset when I see wild animals in cages at zoos. | 5.31 | 1.58 | 0.61 | |

| 6. Breeding animals for their skins is a legitimate use of animals. a | 6.84 | 2.02 | 0.56 | |

| 7. Some aspects of biology can only be learned through dissecting preserved animals such as cats. a | 6.02 | 1.70 | 0.53 | |

| 8. It does not seem right that animals are used in cultural festivals. | 5.22 | 1.86 | 0.52 | |

| 9. The use of animals such as rabbits for testing the safety of cosmetics and household products is unnecessary and should be stopped. | 5.12 | 1.73 | 0.51 | |

| 10. I agree with the use of animals for work. a | 5.97 | 1.77 | 0.50 | |

| Average mean | 5.79 | 1.05 | ||

| Overall 10 item scores b | 57.91 | 10.56 | ||

References

- Bonti Ankomah, S.; Yiridoe, E.K. Organic and Conventional Food: A Literature Review of the Economics of Consumer Perceptions and Preferences; Final Report Submitted to Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada; Organic Agriculture Centre of Canada: Nova Scotia, NS, Canada, 2006; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, K.G. Food Quality and Safety: Consumer Perception and Demand. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Titterington, A.; Cochrane, C. Who Buys Organic food? A Profile of the Purchasers of Organic Food in Northern Ireland. Br. Food J. 1995, 97, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.; Roe, E. Modifying and Commodifying Farm Animal Welfare: The Economisation of Layer Chickens. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 33, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Hamm, U. Information Search Behaviour and its Determinants: The Case of Ethical Attributes of Organic Food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, I.C.; Weeks, C.A.; Wilson, L.R.M.; Nicol, C.J. Consumer Perceptions of Free-Range Laying Hen Welfare. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1999–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann Witzel, J.; Maroscheck, N.; Hamm, U. Are Organic Consumers Preferring or Avoiding Foods with Nutrition and Health Claims? Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakowska Biemans, S.; Tekien, A. Free Range, Organic? Polish Consumers Preferences Regarding Information on Farming System and Nutritional Enhancement of Eggs: A Discrete Choice Based Experiment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Regulation (EC). No 5/2001 of 19 December 2000 Amending Regulation (EEC) No 1907/90 on Certain Marketing Standards for Eggs. Official Journal L 002, 05/01/2001 P.0001-P.0003. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2001/5(1)/oj (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- European Commission (DG ESTAT, DG AGRI), MSs notifications (CIR) (EU) 2017/1185 and Regulation (EC) 617/2008), GTA. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/eggs_en (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Windhorst, H. Patterns of EU egg production and trade: A 2016 status report. In Dynamics and Patterns in EU and USA Egg and Poultry Meat Production and Trade, 1st ed.; Windhorst, H., Ed.; Wissenschafts- und Informationszentrum Nachhaltige Gefluegelwirtschaft: Dinklage, Germany, 2017; Volume 17, pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bornett, H.L.I.; Guy, J.H.; Cain, P. Impact of Animal Welfare on Costs and Viability of Pig Production in the UK. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic 2003, 16, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, I.; Kyriazakis, I. Quantifying the Environmental Impacts of UK Broiler and Egg Production Systems. Lohmann Inf. 2013, 48, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, S.G.; McGahan, E.J. Environmental Assessment of an Egg Production Supply Chain using Life Cycle Assessment; A report for the Australian Egg Corporation Limited AECL Publication No 1FS091A, Australia; Australian Egg Corporation Limited: North Sydney, Australian, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, E.; Boxall, P.; Emunu, J.P.; Boyd, C.; Asselin, A.; Neall, A. Consumer Attitudes, Willingness to Pay and Revealed Preferences for Different Egg Production Attributes: Analysis of Canadian Egg Consumers; Project Report no. 07-03; Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton: Alberta, AB, Canada, 2007; Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/52087/2/PR%2007-03.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Mesias, F.J.; Martinez Carrasco, F.; Martinez, J.M.; Gaspar, P. Functional and Organic Eggs as an Alternative to Conventional Production: A Conjoint Analysis of Consumers’ Preferences. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Y.; Peterson, H.; Li, X. Consumer Attitudes toward Farm-Animal Welfare: The Case of Laying Hens. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2013, 38, 418–434. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, A.; Barreiro Hurle, J.; Lopez Galan, B. Are Local and Organic Claims Complements or Substitutes? A Consumer Preferences Study for Eggs. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L. Consumer Preferences for Cage Free Eggs and Impacts of Retailer Cage Free Pledges. Agribus. Int. J. Agribus. 2019, 35, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Consumer Preference for Eggs from Enhanced Animal Welfare Production System: A Stated Choice Analysis. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association, Washington, WA, USA, 4–6 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs, D.; Wolf, C.A.; Widmar, N.O.; Bir, C.; Lai, J. Hen Housing System Information Effects on U.S. Egg Demand. Food Policy 2019, 87, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerini, F.; Alfnes, F.; Schjoll, A. Organic-and Animal Welfare-labelled Eggs: Competing for the Same Consumers? J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, D.; Loureiro, M.L. Assessing Drivers’ Preferences for Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEV) in Spain. Res. Transp. Econ. 2019, 73, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtnicht, M. German Car Buyers’ Willingness to Pay to Reduce CO2 Emissions. Clim. Chang. 2012, 113, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A. Individual Characteristics and Stated Preferences for Alternative Energy Sources and Propulsion Technologies in Vehicles: A Discrete Choice Analysis for Germany. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pr. 2012, 46, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.D.; Determann, D.; Petrou, S.; Moro, D.; De Bekker Grob, E.W. Discrete Choice Experiments in Health Economics: A Review of the Literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2014, 32, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bekker Grob, E.W.; Swait, J.D.; Kassahun, H.T.; Bliemer, M.C.; Jonker, M.F.; Veldwijk, J.; Cong, K.; Rose, J.M.; Donkers, B. Are Healthcare Choices Predictable? The Impact of Discrete Choice Experiment Designs and Models. Value Heal. 2019, 22, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, D.; Gil, J.M. Valorisation of Food Surpluses and Side-Flows and Citizens’ Understanding; Project Report; Center for Agro-Food Economics and Development: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Available online: Ttps://eurefresh.org/valorisation-food-surpluses-and-side-flows-and-citizens%E2%80%99-understanding (accessed on 22 September 2019).

- Kallas, Z.; Escobar, C.; Gil, J.M. Assessing the Impact of a Christmas Advertisement Campaign on Catalan Wine Preference Using Choice Experiments. Appetite 2012, 58, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamowicz, W.; Boxall, P.; Williams, M.; Louviere, J. Stated Preference Approaches for Measuring Passive Use Values: Choice Experiments and Contingent Valuation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1998, 80, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Roosen, J.; Fox, J.A. Demand for Beef from Cattle Administered Growth Hormones or Fed Genetically Modified Corn: A Comparison of Consumers in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Schroeder, T.C. Are Choice Experiments Incentive Compatible? A Test with Quality Differentiated Beef Steaks. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bekker Grob, E.W.; Hol, L.; Donkers, B.; Van Dam, L.; Habbema, J.D.F.; Van Leerdam, M.E.; Kuipers, E.J.; Essink Bot, M.L.; Steyerberg, E.W. Labeled Versus Unlabeled Discrete Choice Experiments in Health Economics: An Application to Colorectal Cancer Screening. Value Heal. 2010, 13, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, Z.; Vitale, M.; Gil, J.M. Health Innovation in Patty Products. The Role of Food Neophobia in Consumers’ Non-Hypothetical Willingness to Pay, Purchase Intention and Hedonic Evaluation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, Y.; Zander, K. Consumers’ Attitudes on Carbon Footprint Labelling: Results of the SUSDIET Project, Thunen; Working Paper, No. 78; Johann Heinrich Von Thunen-Institut: Braunschweig, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.; Schaffmann, A.L.; Lehberger, M. Consumer Preferences for Different Designs of Carbon Footprint Labelling on Tomatoes in Germany—Does Design Matter? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu Sekyere, E.; Mahlathi, Y.; Jordaan, H. Understanding South African consumers’ Preferences and Market Potential for Products with Low Water and Carbon Footprints. Agrekon 2019, 58, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomarici, E.; Asioli, D.; Vecchio, R.; Nas, T. Young Consumers’ Preferences for Water-Saving Wines: An Experimental Study. Wine Econ. Policy 2018, 7, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katukurunda, S.; Atapattu, M. Water Footprint of Chicken Egg Production under Medium Scale Farming Conditions of Sri Lanka: An Analysis; Conference Paper Presented at the Third International Symposium, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka; South Eastern University of Sri Lanka: Oluvil, Sri Lanka, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ChoiceMetrics, C. Ngene 1.1.2. User Manual & Reference Guide; ChoiceMetrics: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, F.; Frykblom, P.; Lagerkvist, C.J. Using Cheap Talk as a Test of Validity in Choice Experiments. Econ. Lett. 2005, 89, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozmediano, L.; San Juan, C. Escala Nuevo Paradigma Ecologico: Propiedades Psicometricas Con Una Muestra Espanola Obtenida a Traves De Internet [New Ecological Paradigm scale: Psychometric properties with a Spanish simple obtained from the Internet]. Medio Ambiente Y Comport. Hum. 2005, 6, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. Measuring Endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A Revised NEP Scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.; Grayson, S.; McCord, D. Brief Measures of the Animal Attitude Scale. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet World Stats. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats4.htm (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Lancaster, K. A New Approach to Consumer Theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurstone, L. A Law of Comparative Judgement. Psychol. Rev. 1927, 34, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.; Tye, W.; Train, K. An Application of Diagnostic Tests for the Irrelevant Alternatives Property of the Multinomial Logit Model. Transp. Res. Rec. 1977, 637, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Akiva, M.; McFadden, D.; Abe, M.; Bockenholt, U.; Bolduc, D.; Gopinath, D.; Morikawa, T.; Ramaswamy, V.; Rao, V.; Revelt, D.; et al. Modeling Methods for Discrete Choice Analysis. Mark. Lett. 1997, 8, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Greene, W.H. The Mixed Logit Model: The State of Practice. Transportation 2003, 30, 133–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D.L.; Train, K.E. Mixed MNL Models for Discrete Response. J. Appl. Econom. 2000, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelt, D.; Train, K. Mixed Logit with Repeated Choices: Households’ Choices of Appliance Efficiency Level. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinsky, I.; Robb, A.L. On Approximating the Statistical Properties of Elasticities. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1986, 68, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orduno Torres, M.A.; Zein, K.; Ornelas Herrera, S.I.; Guesmi, B. Is Technical Efficiency Affected by Farmers’ Preference for Mitigation and Adaptation Actions Against Climate Change? A Case Study in Northwest Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, V. Public Perception and Poultry Production: Comparing Public Awareness and Opinion of the UK Poultry Industry with Published Data. Animal Welfare Foundation 2017. Available online: https://www.animalwelfarefoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Public-Perception-and-Poultry-Production-Comparing-public-awareness-and-opinion-of-the-UK-poultry-industry-with-published-data.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

| Attributes | Levels |

|---|---|

| Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (%) | 0% 10% 20% 30% |

| Reduction of water use (%) | 0% 10% 20% 30% |

| Price (€/6 eggs) | Caged * (€0.70; €0.85; €1.00; €1.15) Barn (€1.20; €1.35; €1.50; €1.65) Free range (€1.70; €1.85; €2.00; €2.15) Organic (€2.45; €2.60; €2.75; €2.90) |

| Eggs from Hens Raised in Cages | Eggs from Hens Reared in Barn | Free-Range Eggs | Organic Eggs | None of the Options | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price for half a dozen (€/6 eggs) | €0.85 | €1.65 | €2.00 | €2.90 | I would not buy any of the four options. |

| Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (%) | 10% | 30% | 0% | 20% | |

| Reduction of water use (%) | 10% | 30% | 20% | 0% |

| Variables | Categories | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 49.76% |

| Male | 50.24% | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 10.53% |

| 25–34 years | 17.22% | |

| 35–49 years | 32.54% | |

| 50–64 years | 25.84% | |

| 65 years or over | 13.88% | |

| Average age | 44.31 | |

| Household income | €500–999 | 10.72% |

| €1000–1499 | 20.00% | |

| €1500–1999 | 18.95% | |

| €2000–2499 | 14.93% | |

| €2500–2999 | 13.01% | |

| €3000–4999 | 14.35% | |

| €5000 or more | 3.73% | |

| I do not know | 4.31% | |

| Household size | Average | 3 |

| Educational level | Unfinished primary studies | 1.24% |

| Primary studies | 6.41% | |

| Secondary studies (Professional training, etc.) | 40.38% | |

| Higher education (University/professional training) | 51.96% | |

| Margin of Error | Margin of error for a sample of 1045 respondent, assuming a 95% level of confidence | 3.03% |

| Variable | Description | %Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Female | It is a dummy variable. It takes the value 1 if participant is a female and 0 otherwise. | 49.76% |

| Age 40 | It is a dummy variable. It takes the value 1 if participant is under 40 years old and 0 otherwise. | 43.15% |

| Lhinc | It is a dummy variable. It takes the value 1 if household monthly income is less than €1500 and 0 otherwise. | 30.72% |

| Environmentalist | It is a dummy variable. It takes the value 1 if the average score of the NEP scale is higher than the sample average score and 0 otherwise. | 50.43 * |

| Animalist | It is a dummy variable. It takes the value 1 if the average score of the animal attitude scale is higher than the sample average score and 0 otherwise. | 46.22% * |

| Random Parameters in Utility Functions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | Std. Err. | Pr > [z] | |

| Greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction 10% | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| GHG reduction 20% | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| GHG reduction 30% | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Water reduction 10% | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.37 |

| Water reduction 20% | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Water reduction 30% | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Caged | 1.95 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Barn | 3.66 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Free Range | 7.46 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Organic | 0.13 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| Nonrandom parameters in utility functions | |||

| Coeff. | Std. Err. | Pr > [z] | |

| Price—Caged | −1.47 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| Price—Barn | −0.74 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Price—Free Range | −2.38 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Price—Organic | −0.23 | 0.34 | 0.48 |

| Standard deviations of random parameters | |||

| S.D. GHG reduction 10% | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.32 |

| S.D. GHG reduction 20% | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| S.D. GHG reduction 30% | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Water reduction 10% | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.88 |

| S.D. Water reduction 20% | 1.45 | 0.81 | 0.07 |

| S.D. Water reduction 30% | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Caged | 3.72 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Barn | 2.16 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Free Range | 3.73 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Organic | 4.23 | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| Observations | 8360 | ||

| Respondents | 1045 | ||

| Wald Chi2 (24) | 11,442.33 | 0.00 | |

| Log Likelihood | −7733.73 | ||

| Restricted log likelihood | −13,454.90 | ||

| McFadden Pseudo R-squared | 0.4252 | ||

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 15,515.50 | ||

| Willingness to Pay (WTP) Estimates (€/6 Eggs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | Std. Err. | Pr > [z] | |

| Caged without any reduction | 0.46 | 0,17 | 0.00 |

| Barn without any reduction | 3.23 | 2.01 | 0.10 |

| Free range without any reduction | 2.59 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Organic without any reduction | −4.83 | 330.93 | 0.98 |

| 10% reduction of GHG emissions in Caged | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.36 |

| 10% reduction of GHG emissions in Barn | 0.52 | 0.68 | 0.44 |

| 10% reduction of GHG emissions in Free range | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| 10% reduction of GHG emissions in Organic | 1.65 | 234.74 | 0.99 |

| 20% reduction of GHG emissions in Caged | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| 20% reduction of GHG emissions in Barn | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.24 |

| 20% reduction of GHG emissions in Free range | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 20% reduction of GHG emissions in Organic | 2.47 | 86.34 | 0.97 |

| 30% reduction of GHG emissions in Caged | 0.51 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| 30% reduction of GHG emissions in Barn | 1.03 | 0.91 | 0.25 |

| 30% reduction of GHG emissions in Free range | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 30% reduction of GHG emissions in Organic | 3.25 | 23.91 | 0.89 |

| 10% reduction of water use in Caged | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| 10% reduction of water use in Barn | 0.29 | 3.11 | 0.92 |

| 10% reduction of water use in Free range | 0.09 | 1.84 | 0.96 |

| 10% reduction of water use in Organic | 0.92 | 140.58 | 0.99 |

| 20% reduction of water use in Caged | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| 20% reduction of water use in Barn | 0.64 | 0.96 | 0.50 |

| 20% reduction of water use in Free range | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 20% reduction of water use in Organic | 2.02 | 38.53 | 0.95 |

| 30% reduction of water use in Caged | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| 30% reduction of water use in Barn | 0.97 | 0.55 | 0.08 |

| 30% reduction of water use in Free range | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 30% reduction of water use in Organic | 3.05 | 71.05 | 0.96 |

| Random Parameters in Utility Functions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | Std. Err. | Pr > [z] | |

| GHG reduction 10% | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| GHG reduction 20% | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| GHG reduction 30% | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Water reduction 10% | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Water reduction 20% | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| Water reduction 30% | 0.35 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Caged | 2.10 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Barn | 3.06 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Free Range | 6.83 | 0.46 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Organic | −2.30 | 0.99 | 0.02 |

| Non-random parameters in utility functions | |||

| Price—Caged | −1.71 | 0.29 | 0.00 |

| Price—Barn | −0.77 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| Price—Free range | −2.54 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Price—Organic | −0.23 | 0.34 | 0.50 |

| ASC—Caged * Female | −0.18 | 0.29 | 0.51 |

| ASC—Barn * Female | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.60 |

| ASC—Free range * Female | −0.38 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| ASC—Organic * Female | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.58 |

| ASC—Caged * Age40 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Barn * Age40 | 1.47 | 0.23 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Free range * Age40 | 2.02 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Organic * Age40 | 2.93 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Caged * Lhinc | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.14 |

| ASC—Barn * Lhinc | −0.55 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Free range * Lhinc | −1.57 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Organic * Lhinc | −1.12 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Caged * Environmentalist | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.71 |

| ASC—Barn * Environmentalist | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| ASC—Free range * Environmentalist | 1.02 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Organic * Environmentalist | 1.53 | 0.39 | 0.00 |

| ASC—Caged * Animalist | −0.23 | 0.32 | 0.47 |

| ASC—Barn * Animalist | −0.18 | 0.22 | 0.41 |

| ASC—Free range * Animalist | −0.14 | 0.26 | 0.58 |

| ASC—Organic * Animalist | −0.02 | 0.38 | 0.94 |

| Standard deviations of random parameters | |||

| S.D. GHG reduction 10% | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| S.D. GHG reduction 20% | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.17 |

| S.D. GHG reduction 30% | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Water reduction 10% | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Water reduction 20% | 1.01 | 1.46 | 0.48 |

| S.D. Water reduction 30% | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| S.D. Caged | 3.27 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Barn | 2.45 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Free range | 3.43 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| S.D. Organic | 4.82 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Observations | 8360 | ||

| Respondents | 1045 | ||

| Wald Chi2 (44) | 11,512.99 | 0.00 | |

| Log Likelihood | −7698.40 | ||

| Restricted log likelihood | −13,454.90 | ||

| McFadden Pseudo R-squared | 0.43 | ||

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 15,484.8 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahmani, D.; Kallas, Z.; Pappa, M.; Gil, J.M. Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226218

Rahmani D, Kallas Z, Pappa M, Gil JM. Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts? Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226218

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahmani, Djamel, Zein Kallas, Maria Pappa, and José Maria Gil. 2019. "Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts?" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226218

APA StyleRahmani, D., Kallas, Z., Pappa, M., & Gil, J. M. (2019). Are Consumers’ Egg Preferences Influenced by Animal-Welfare Conditions and Environmental Impacts? Sustainability, 11(22), 6218. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226218